6 minute read

NARRATIVE

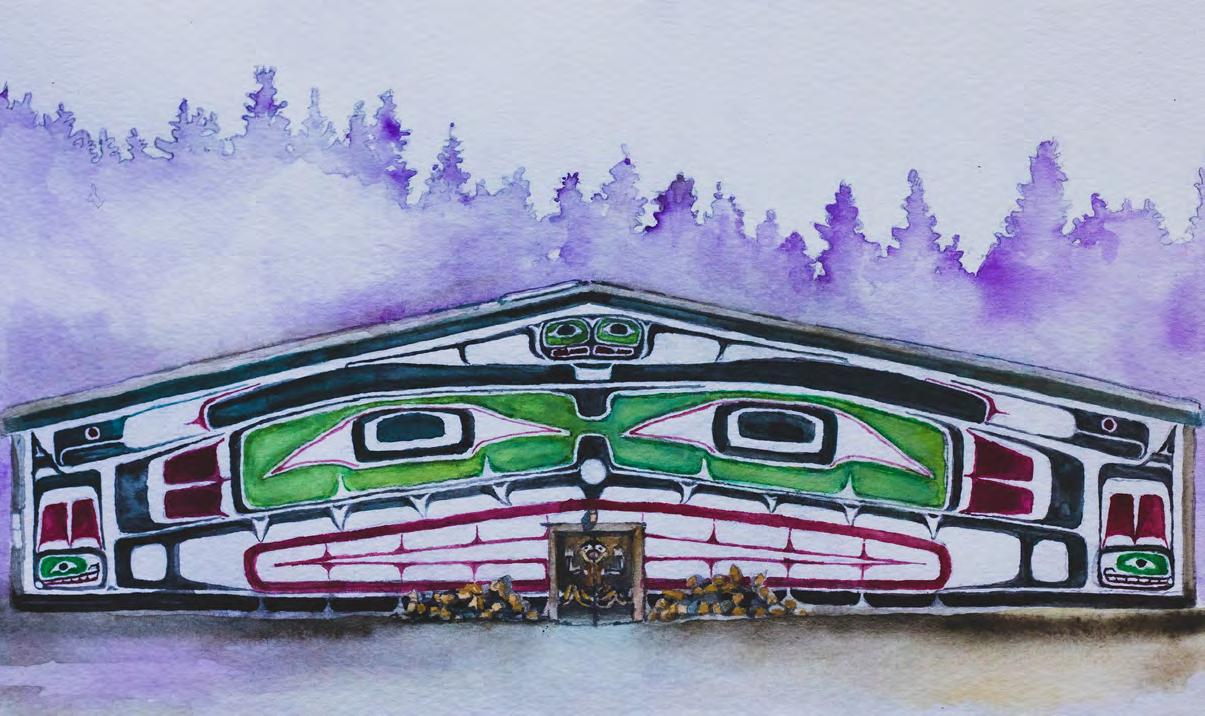

WORDS BRUCE CAMERON, ILLUSTRATION SIERRA LUNDY

SAFE PLACE IN A STORM: THE HAIDA RETURN

Advertisement

in this age of COVID-19, I’m grateful to live in a place where public health has been taken seriously and the impact of the crisis has been kept to a minimum. It is easy to become complacent and it’s even easier to forget the lessons learned during previous pandemics, separated as we are by the fog of time from events like smallpox outbreaks in the 1800s and the Spanish flu in 1918.

As an avid student of history, I always stop at heritage signs to linger and learn details of the past. But even more compelling are the stories not widely told: those filled with heroism, treachery, perseverance and pestilence, such as the story of the smallpox outbreak of 1862. My wife and I love to travel throughout BC and in particular around Vancouver Island, visiting small villages, exploring back roads, discovering abandoned town sites and enjoying beautiful beaches. One place that holds a special place in our hearts is Alert Bay, located on Cormorant Island at the north end of Vancouver Island. We love it so much that we commissioned a local Kwakwaka’wakw artist in Alert Bay to craft our wedding rings, engraving them with Kwakiutl motifs of a whale and an eagle.

Each time we visit Alert Bay, special things happen. Once, we rounded a corner on the road just in time to see a humpback whale breach in the ocean, right in front of us. And another time, most fortuitously, we met the local Chief, who invited us to attend a potlatch at the Namgis First Nation’s Big House.

Knowing a little about First Nations customs and the special place potlatches occupy in the culture, we excitedly accepted the invitation, changing our travel plans to stay in the area longer. In the not-too-distant past, the potlatch was considered controversial, representing such an antithetical challenge to the conquering “white” culture that it had been banned. Potlatches were prohibited by law until the 1970s in many parts of North America. The ceremonies, held in long houses over several days, include story telling, singing and dancing. The potlatch was, and still remains, one of the central pillars of the oral culture of First Nations, ensuring continuity of stories, and a gracious, heartfelt transfer of wealth (whether it be a treasured carving, or a blanket or a piece of copper).

We felt blessed to be invited by the Chief. But the blessing was more of a gift than we could have imagined on that weekend in 2012. Not only was the potlatch hosted by celebrated storyteller and carver Beau Dick, it also commemorated a tragic piece of history—a story that is timely today.

As my wife and I watched the day before the potlatch, an exquisitely carved canoe pulled up to a wharf and a group of Haida disembarked. They had arrived on the island to mark 150 years since the Kwakiutl peoples had helped the Haida as they fled, increasingly diseased and overcome with smallpox, north from Fort Victoria toward their home villages on Haida Gwaii. Smallpox had ravaged the entire West Coast, spreading after a sick passenger from San Francisco landed in the small colonial outpost of Fort Victoria.

The shameful history of that period has been examined by others ( The Vancouver Sun ’s Stephen Hume wrote an excellent article in April 2012 on the 1862-63 smallpox epidemic, and the Haida detailed many of the events in the Haida Laas online journal). Each documents the scope of the calamity that engulfed the West Coast and especially the many First Nations, whose populations were decimated by up to 80 per cent.

Residents of BC will recognize the names of many of the key actors in the unfolding calamity, from James Douglas, the Governor General of Vancouver Island, to Doctor Helmcken and Doctor Tolmie, elected members of the new colony’s legislature. As the smallpox epidemic gained a foothold, Douglas championed “the raising of funds for a hospital,” but the legislature, in an echo of COVID battles to come, “refused enforced quarantines as an infringement on personal liberties.” Even more galling was the fact that Tolmie and Helmcken, who both had experience dealing with smallpox outbreaks in 1837 and 1857, voted against quarantine measures. Despite attempts by Helmcken to inoculate some of the First Nations (there was a workable vaccine at the time), the legislature closed down and the leaders abandoned the colony, leaving local leaders like Police Commissioner Pemberton to cobble together a coherent response.

Pemberton, egged on by a panicked white population aghast at the spread of the disease among the First Nations (which made up about half of the 5,000 or so people living in or near Fort Victoria), resorted to the threat of violence. Pemberton forced the sick and dying Haida and several other groups into their massive, sea-going canoes and had them towed by HMS ships Grappler and Forward north toward Fort Rupert. Little is known of that horrific voyage, as few of the exiled people survived the journey, but the decision to push the pestilence up the island effectively sealed the fate of thousands of villages whose populations perished in the next 18 months as refugees arrived on their shores and infected bodies washed up on their beaches.

The 2012 potlatch hosted by Beau Dick was timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the Haida in 1862, and provided an opportunity for the Haida to formally thank the Kwakwaka’wakw people for their help during a time of despair and death.

The scale of devastation is hard to picture now. Beau Dick, who passed away a few years ago, recounted hearing stories from his ancestors of 1,200 big sea-going canoes full of Haida travelling south in the year prior to the outbreak past Alert Bay to Mak’toli (Fort Victoria). Only 24 canoes limped back into Bones Bay the following summer.

The full tale of the 1862 smallpox pandemic is a heartwrenching account of needless death and suffering, caused by hapless dithering among politicians, who were trying to survive a plague while facing racist xenophobic sentiment and growing panic at the edge of the colonial world. At that moment of history, more than half of the population of BC was Indigenous (about 32,000 of the 50,000 people), and while a few brave missionaries like Leon Fouquet and Alexander Garrett risked their lives to help provide vaccinations, the proud, self-sufficient peoples of the West Coast were mostly left to die on their own. The enduring power and resilience of First Nations culture is a testament to the survival of those peoples and their stories.

Beau Dick’s potlatch of 2012 unfolded in a mesmerizing display of artistry—starting with the carvings on the exterior of the Namgis Big House to the dazzling totems and the dancers moving enticingly around a blazing fire inside, amid chanting and drumming. One of the many highlights was the extraordinary display of masks, from small bears and frogs to an absolutely massive raven, which had to be supported by several people as the dancer moved around the fire. And, of course, it was a momentous occasion when the Haida took the floor.

We were blessed to have been there for the potlatch and for the Haida’s return to thank the descendants of those who reached out when others turned them away. In these uncertain times, as in centuries past, we all need a safe place in a storm.

Do you have a good story to tell—and the ability to write it? Boulevard readers are invited to submit stories for consideration and publication in the Narrative section. Stories should be 800 to 1,200 words long and sent to managing editor Susan Lundy at lundys@shaw.ca. Please place the word “Narrative” in the subject line.