10 minute read

Under the dome: conserving an elaborate Victorian glass centrepiece

Under the dome: conserving an elaborate Victorian centrepiece

Margot Murray, Ceramics Conservator

Advertisement

Under a glass dome sits an elaborate glass centrepiece featuring a busy scene of colourful birds sitting on delicately worked fountains with trees, flowers and even a fine ship, all emerging from a turbulent sea of glass flakes (C.772-1936). With so much to take in, it is easy to overlook the careful craftsmanship in the trailing patterns of the airy fountains or the impossibly thin rigging on the masts of the ship. When the centrepiece was damaged and required reconstruction, the fragility of the object created a unique conservation challenge.

Not much is known about the Victorian glassworkers who created such elaborate, decorative novelty objects in lamp-worked glass. Similar fountains and arrangements of lamp-worked birds with spun glass tails are found in other collections in the UK, particularly in Liverpool and St Helens, Merseyside, and the West Midlands, which were centres for glass making throughout the nineteenth century. Given the delicate nature of these objects, it is likely that many have not survived.

The centrepiece, donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1936, is composed of seven lamp-worked glass parts. Lamp-work (also known as flame-work) uses a flame to soften prefabricated glass tubes and rods to create delicate objects. A range of colours and techniques were employed to create the fountains, the birds with spun glass tails, the delicate ship and the ‘sea’ of glass fibres and flakes. The lamp-worked parts were adhered to a crudely cut, square plate glass base, which is surprising when compared to the craftsmanship of the lamp-worked parts. The dome has a thin velvet strip around its base and is held in place by four plate glass corners, the corners and velvet appear to have been added after the object was acquired (Fig. 1). The base and corners are noticeably different in colour. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was used to compare the elemental compositions of the different types of glass, and the data can also be used to compare with other plate glass from the period.1

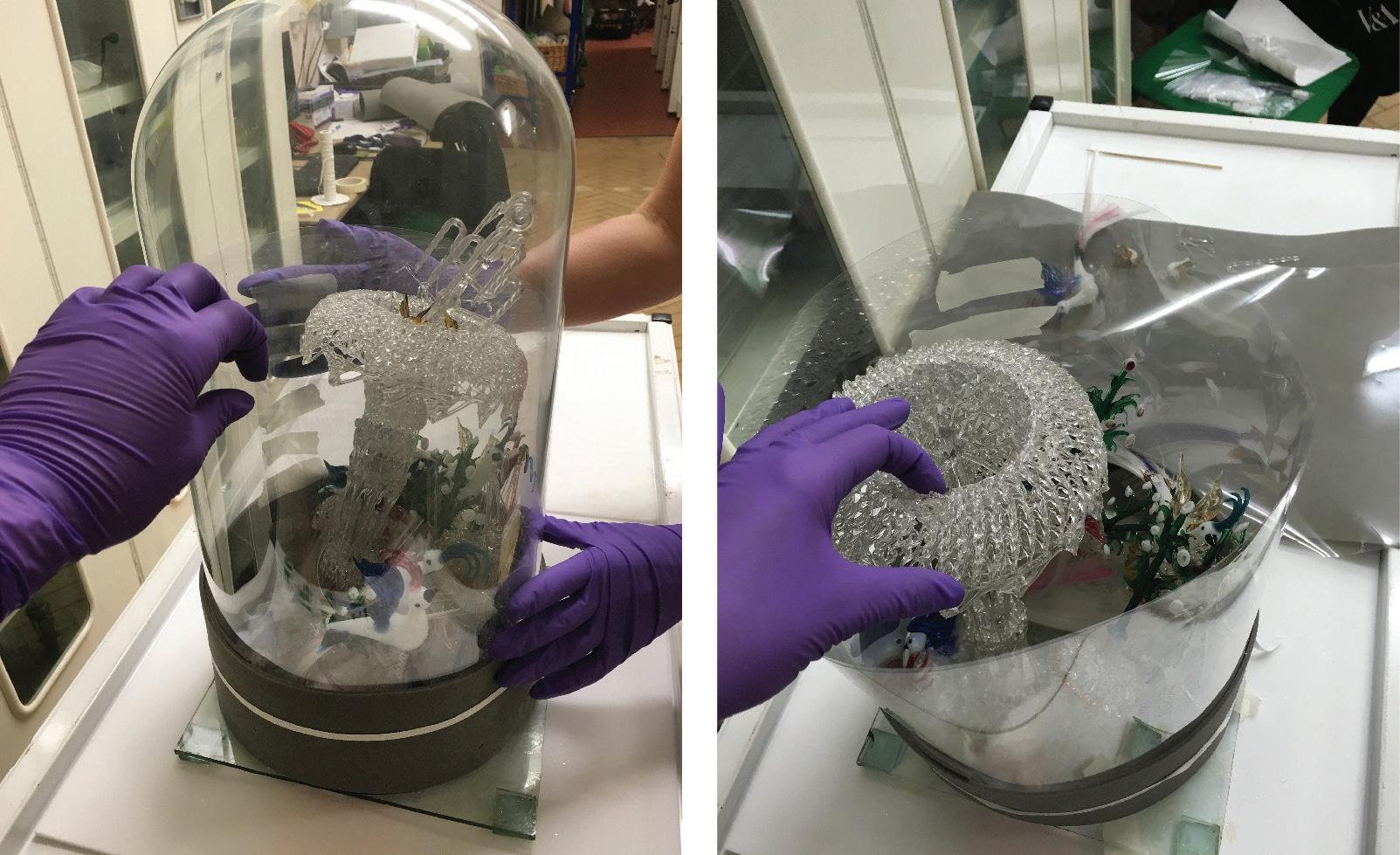

The object suffered damage in transit in 2003 (Fig. 2). The fountain had collapsed inside the dome, the birds and small water spout had broken off the large fountain, and all the lamp-worked parts were no longer standing on their bases. Breaks had occurred across all parts, leaving 31 fragments loose inside the dome. The first challenge was removing the dome without the pieces collapsing further. A tube of Melinex (polyester film) was fitted around the lower two thirds of the dome and attached to the glass base with adhesive tape. The dome could then be lifted off, leaving the tube to support the fragments (Fig. 3).

After the fragments had been removed, it appeared that many of the delicate components had escaped major structural damage. However, a large amount of adhesive that had been used to adhere the lampworked parts to the base obscured the full extent of the structural damage. Several different adhesives had been applied to the object in the past. In most areas the adhesive was pale yellow or brown and soluble in water, suggesting an animal protein glue. A thick, yellowed adhesive present at joins in the ship, the small fountains and where the small birds had been reattached to the front small fountain, was not soluble in water, acetone or industrial methylated spirits (IMS), suggesting it may be an aged epoxy or polyester resin.

During the removal of the thick adhesive at the base of each lamp-worked component, it quickly became clear that the bases were extensively cracked and broken, only remaining together due to the excessive amount of adhesive covering the original glass surface. The adhesive was slowly removed with a scalpel, softening areas with water where possible. Working in one small area at a time meant that the tiny glass fragments could be bonded back into position immediately with Paraloid B-72 (approximately 40% w/v solution in acetone). Paraloid B-72 (ethyl methacrylate methyl acrylate copolymer) was chosen for its long-term chemical stability and reversibility.

Some previous repairs were stable and not visually obtrusive, such as at the wings of several birds, so were left joined and noticeable areas of excess adhesive were removed. In other areas, fragments had been bonded in the wrong position. Where the previous joins were unstable or incorrectly positioned, the joins were dismantled, cleaned and bonded using Paraloid B-72.

Finding correct joins in the colourless lampworked glass was particularly challenging. The small fragments had several tiny points of contact and

V&A Conservation Journal No.67 V&A Conservation Journal No.67

Fig. 1 Glass centrepiece, C.772-1936, at time of acquisition © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig. 2 Glass centrepiece before treatment (Photography by F. Jordan © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Fig. 3 During conservation, removing the dome and separating fragments (Photography by M. Murray © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Fig. 4 During conservation, bonding the completed lamp-worked parts to the base (Photography by F. Jordan © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

break edges were difficult to see in the colourless glass latticework, even with magnification. When the correct placement was found, it was just as difficult to hold the fragment in position for bonding. Bonding continued gradually until the delicate lamp-worked parts were ready to be reattached to the base (Fig. 4). In areas where the Paraloid joins failed to hold or where extra strength was required, Hxtal NYL-1 (epoxy resin) was applied to the join. Once all the parts were securely attached to the base, the sea of glass fibres and flakes was reintroduced. Finally, the centrepiece was covered by the newly cleaned dome and the corners secured to the base with Paraloid B-72.

The treatment of the centrepiece was a practical challenge, requiring patience and a steady hand to relocate the fragments, but the more time that was spent working on the object the more enchanting it became. Now that the centrepiece is together once again it is ready for display in the Glass Galleries, where it can be enjoyed by all (Fig. 5).

Acknowledgements This conservation work has been made possible with funds raised in memory of Jonathan Nevitt.

I am grateful to my conservation colleagues, Fi Jordan and Victoria Oakley, for their advice, and to my curatorial colleagues, Reino Liefkes, Judith Crouch and Florence Tyler, for their expertise and assistance with this project.

References 1. Manca, R, Burgio, L, Analysis Report 19-86-RM-LB Glass centre-piece – C.772-1936, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2019.

V&A Conservation Journal No.67

Fig. 5 Glass centrepiece after conservation © Victoria and Albert Museum, London V&A Conservation Journal No.67

A spoon full of care: conservation and packing for delicate sherbet spoons

Boudewien Westra, Furniture Conservator

Figs. 1 and 2 Transparent tray with Sherbet spoons (L) and Sherbet spoon 1289-1874 (R), before conservation treatment (Photography by P. Kevin and B.C. Westra © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Much of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection is currently stored at Blythe House in West London but will be moving to Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in East London, where the Museum will open two interconnected sites in 2023: a Collection and Research Centre (CRC) at Here East and a new museum at Stratford Waterfront. Consequently, this will create an extraordinary opportunity for the public to see more of the V&A’s collections.

Over the past two years, the Blythe House Decant Collections Project Team have been preparing the collections for this move. Part of this team is a group of conservators who treat and prepare objects to stabilise them before they are packed and transported to CRC. Two furniture conservators have been working steadily on over seven hundred objects assessed as requiring treatment, including pieces of furniture and other wooden objects such as picture frames, carvings, architectural elements, gilded objects and puppets. Most of the treatments involve stabilisation of the objects to minimise potential risk of damage during transport. Every object is unique and therefore the conservation work can vary from structural treatments to consolidating decorative surfaces and less interventive approaches such as providing bespoke packaging or handling boards. Sometimes a combination of these is carried out to achieve a satisfying and safe result for the object. This article will focus on a group of fragile and awkwardly-shaped sherbet spoons as a good example to illustrate a combination of interventive treatment and simple but effective specialist packing as the best solution for their safe transportation and future storage.

Sherbet spoons are used in the West Asian, Indian subcontinental and Indonesian tradition surrounding sherbet. Sherbet is a sweet cordial drink prepared from fruits or flower petals and is usually served chilled in a ceramic basin. The spoons were placed on the side of the bowls, with their handles balanced, floating on top of the sherbet. Guests would drink from the spoon then place the spoon back in the basin for others to use. The V&A’s collection of sherbet spoons is extensive and highly decorative, and it is thought to have been used by the well-to-do. Sherbet spoons are generally made of pear- and boxwood and consist of two parts: a long handle joined to the bowl-section by a socket. A large carved rosette is usually placed on top of the socket. Occasionally spoons were decorated with paint and finished with a clear varnish. However, the majority of these spoons remain unfinished. Most of the spoons in the Museum’s collection originate from Abadah in Iran and were made between 1800 – 1900.¹

V&A Conservation Journal No.67 V&A Conservation Journal No.67

Fig.3 Detail of broken bowl-section and old facings on spoon 1282-1874 before conservation (Photography by B.C. Westra © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The spoons are very fragile as they are carved from very thin sections of wood and have delicate pierced work, so it is important to store them correctly to avoid damage. Storage conditions were not ideal as the transparent trays containing the spoons were crowded and the spoons lacked sufficient support; therefore, to ensure safe transport to CRC, it was necessary to perform conservation treatments and provide bespoke packaging for the twelve spoons.

Some of the highly decorative pierced carvings in the very thin bowl-section of the spoons were fractured (Figs. 1 and 2). Some spoons had residues of old glue and supportive facings from previous repairs. Old paper tabs had been used during previous repairs to bridge gaps and strengthen joins on some of the bowl-sections. These had to be removed because they were too small and the adhesive had failed, resulting in a loss of their supportive function (Fig. 3).

Several elements of the decorative carving were broken and had been re-adhered in the past during previous treatments. However, most of these glue joints failed or fragments were out of alignment. Therefore, it was necessary to remove the adhesive residues and to reposition the loose fragments.

Fig. 4 1282-1874 with Japanese paper after conservation (Photography by B.C. Westra © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Due to the thin and fragile nature of the bowl-section of the spoons, it was decided to apply Japanese paper facing adhered with wheatstarch to support the breaks. In some cases, the facing was applied to bridge the losses and achieve more unity of the bowl-section. A few layers of Japanese paper provided enough strength to hold the bowl-section together and the water-based starch can be removed easily in the future without damaging the object (Fig. 4).

After conservation was completed, a bespoke tray was made for each of the spoons using Plastazote foam. Parts of the foam were ‘scooped-out’ to form a rebate, enabling the bowl of the spoon to rest into the foam. The spoons were then secured with cotton tape to avoid any undesirable movement within their Plastazote tray (Figs. 5 and 6). This combined approach of treatment and bespoke supportive packaging will provide a safe and secure way to transport them and ideal storage conditions for the future.

References 1. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O109573/sherbet-spoonunknown/ [Accessed 7 January 2020]

Fig.5 and 6 Range of Sherbet spoons after conservation treatment and positioned in a Plastazote tray (Photography by B.C. Westra © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)