67 minute read

Up Front

Clinics in the News

JOE HOWELL

Stanton Foundation First Amendment Clinic wins case for TSEL

The Stanton Foundation First Amendment Clinic, representing the nonprofit group Tennesseans for Sensible Election Laws, recently prevailed in a case that sought to declare unconstitutional a Tennessee election law that criminalized false speech in opposition to a political candidate. The clinic is directed by Assistant Clinical Professor G.S. Hans.

TSEL planned to distribute a mailer criticizing state Rep. Bruce Griffey, who represents Paris, Tennessee, after Griffey introduced a bill that would have required anyone convicted of sexual offenses against minors to undergo “chemical castration” if released on parole. The mailer accused Griffey of promoting “an agenda the Nazis would love,” and urged voters to “Vote No on Bruce Griffey—He’s literally Hitler!” Because the statements in the mailer were false and were in opposition to a political candidate, TSEL’s distribution of the mailer could have led to criminal charges against the organization under state law.

After oral arguments on TSEL’s summary judgment motion, Davidson County Chancellor Judge Ellen Hobbs Lyle ruled the statute was unconstitutional, citing several arguments presented in TSEL’s brief.

Jimmy Ryan ’21 successfully argued against the state’s motion to dismiss this case in May, and Hans argued the motion for summary judgment in July. Paige Tenkhoff ’20, Amber Banks ’20 and Cole Browndorf ’20 also served on the clinic legal team working on the case. Hans believes the state will appeal. “If they do, the clinic and our students will continue to work on the case in the coming academic year,” he said.

Immigration Practice Clinic students support communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19

Three Immigration Practice Clinic students—Cloe Anderson ’21 (BA’18), Grace Ko ’21 and Sarah Dvorak ’22—worked pro bono with staff from the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition, the Asian and Pacific Islanders of Middle Tennessee, the Tennessee Asian Pacific American Bar Association and the Hispanic Bar Association to assist in drafting a resolution passed by the Metro Nashville Council that addressed discrimination and harassment against Asian and Pacific Islanders during the COVID-19 pandemic. The students also produced a library resource guide with the help of Vanderbilt Law Librarian Sarah Dunaway. The guide, COVID-19 and Racism: Legislative Responses, charts legislative responses to COVID. “We learned a lot about local government and the process for passing a resolution,” said Ko. “It was a very rewarding experience.”

Youth Opportunity Clinic joins emergency petition

Students in the Youth Opportunity Clinic joined with nearly 40 other criminal justice advocacy groups in Tennessee to submit a legal petition to the state Supreme Court to release people from jails and prisons during the coronavirus outbreak. “Legal advocates throughout the state asked the Court to release people who pose a low risk to the public and those who are at heightened risk for coronavirus complications from state jails and prisons while the judicial state-ofemergency order remains in place, unless the state can demonstrate that their release would endanger someone’s safety,” said Youth Opportunity Clinic director Cara Suvall. “The goal is to avoid dangerous outbreaks of COVID-19 in Tennessee’s jails, prisons and detention centers and to protect those whose continued incarceration is necessary.”

Criminal Justice Clinic represents criminal defendants in challenging times

Josh Stanton knew that litigating cases during the COVID-19 pandemic would present some daunting challenges when he joined the Vanderbilt Law faculty as a Criminal Justice Clinic Fellow in August.

After earning his law degree at New York University and serving as a law clerk to Judge Jon Phipps McCalla of the Western District of Tennessee, Stanton was a public defender in Memphis for four years. He was working as a criminal defense lawyer at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan in New York when he accepted the newly endowed Criminal Justice Clinic Fellowship at Vanderbilt last spring. He now works with Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs Susan Kay ’79 to supervise students in Vanderbilt’s Criminal Justice Clinic.

This year, Kay, Stanton and their students were forced to adapt quickly to the limitations imposed by the pandemic. Pairs of students normally visit the Metro Nashville jail to meet with their clients. But with access to clients limited to a single computer screen in a small room, only one student at a time can safely interview clients in custody.

With courts’ capacity to hear criminal cases reduced and jury trials prohibited, clinic students worked on bond motions seeking release for clients awaiting trial. “When bond motions are denied, our clients have to choose whether to take a guilty plea to get out of custody or to stay in jail awaiting trial, where their risk of contracting COVID is higher,” Stanton said. “When clients take a guilty plea just so they can be released, there’s a conviction on their records. That’s a big downside.”

Despite the difficult conditions, some students opted to appear in court when permitted. “Students are navigating the situation as well as possible and developing relationships with clients,” Stanton said. “They’re learning by doing the nuts and bolts of any criminal case—reviewing discovery, developing investigation plans, drafting motions and even negotiating with prosecutors.”

Kay launched the Criminal Justice Clinic in 1980 and has directed the law school’s clinical education program since 2001. “We are delighted to have Josh working with us—in addition to his experience as a public defender, he brings a fresh perspective and a keen intellect to our clinical program,” she said.

Students in the News

Ramon Ryan ’21 wins ABA K. William Kolbe Writing Competition

Ramon Ryan won the American Bar Association’s 2020 K. William Kolbe Writing Competition for his Note, “The Fault in Our Stars: Challenging the FCC’s Treatment of Commercial Satellites as Categorically Excluded from Review under the National Environmental Policy Act,” published in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law last fall.

Ryan chose to research the topic after learning that the FCC did not require any assessments of the environmental impact of commercial satellites before approving their launch, an omission he believes violates the National Environmental Policy Act. “One might assume that the FCC evaluates new commercial satellite projects for their environmental impact, both to comply with NEPA and to avoid scenarios such as a company using mercury as a satellite propellant or permanently altering the aesthetic of the night sky,” Ryan states in his article, “but this assumption would be incorrect.”

His paper recommends that the FCC update its treatment of satellites to include environmental review under NEPA and proposes a process for conducting the reviews.

The prize-winning paper received national publicity even before its publication, with reports on Ryan’s findings appearing in Scientific American, Business Insider, Futurism and other publications. The paper recently was cited in a legal challenge filed by Viaset, a global communications company, challenging the FCC’s approval of a request by SpaceX to modify the orbits of some satellites in its massive Starlink network, which will ultimately comprise approximately 12,000 satellites.

Ryan started a new student organization, the Space Law Society, as a 1L and was editor-in-chief of the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law in 2020–21. He plans to join the government contracts group at Bass Berry & Sims in Nashville after graduation. He will serve as a clerk for Judge Todd Hughes of the Federal Circuit in 2023–24.

Matt Fitzgerald ’20 wins Adm. John S. Jenkins Writing Award

Matt Fitzgerald, a captain in the U.S. Army JAG Corps, won the 2020 Rear Admiral John S. Jenkins Writing Award for his essay, “Thank Me for My Service: An Ethics Oversight in DoD Social Media Policy.” The award recognizes the best paper written in the past year on a military justice topic. Fitzgerald wrote the paper, which will be published in the Harvard National Security Law Journal, as an independent study project under the supervision of Professor Michael A. Newton.

Fitzgerald’s paper addresses financial compensation that military servicemembers receive for service-related content they produce on social media platforms. Although federal ethics rules preclude most servicemembers from using their public positions for private gain, Fitzgerald found many examples of military personnel in uniform who received compensation for producing and posting Facebook and YouTube videos in which they endorsed dietary supplements, clothing brands and other products and services. “The current DoD policy regime is ill-equipped to address these for-profit ventures,” he said. His paper proposes policy recommendations designed to promote, reward and facilitate military content creation on social media while also supporting compliance with federal ethics rules.

“Matt identified a gaping flaw in the current ethics guidance that is hiding in plain sight,” Newton said. “He documented the scope of the problem and offered solutions that are already beginning to bear fruit in the form of reframed DoD guidance.”

Cort Thompson ’20 wins the ASIL 2020 Richard Baxter Military Prize

Thompson's paper, "Avoiding Pyrrhic Victories in Orbit: A Need for Anti-Satellite Arms Control in the 21st Century," was published in the SMU Journal of Air Law and Commerce.

The annual American Society of International Law Richard Baxter Military Prize recognizes a paper written by an active-duty member of the armed forces that “significantly enhances the understanding and implementation of the law of war.”

Thompson became interested in laws that regulate military anti-satellite weapons after India destroyed one of its own defense satellites in 2019 by hitting it with an anti-satellite weapon. The impact created approximately 270 pieces of trackable debris that remain in orbit as a long-term hazard to future space launches. “India’s demonstration of its ASAT capability was an important reminder that space is a global commons, and the activities of one state affect those of every other nation with a space program,” Thompson said.

Thompson’s paper issues a call to action for states to negotiate updates to the long-standing treaties and other international agreements governing outer space to prevent any single nation from deliberately using anti-satellite weapons to create artificial orbital debris. He compares the comprehensive set of laws needed to address space activities, including space debris and satellite launches and orbits, to the law of the sea. While international legal regime addressing orbital space was established by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and other treaties negotiated in the 1970s, Thompson asserts that updates are long overdue. “These treaties were concluded at the height of the Cold War with an emphasis on preventing nuclear weapons from being stationed in orbit. Today, there is much work to be done to address contemporary military capabilities in space,” he said.

Thompson wrote the paper as an independent research project supervised by Professor Ganesh Sitaraman. His column based on the paper appeared in the Lawfare blog. Now serving in the JAG Corps, he was a Thomas Beasley Scholar at VLS, where he earned his law degree through the Army’s Funded Legal Education Program. He earned his undergraduate degree with honors at West Point.

Cort Thompson introduced Gen. Michael V. Hayden for the 2019 Chancellor’s Lecture Series.

PEYTON HOGUE

Kevin Witenoff ’21 selected as ACS Next Generation Leader

Kevin Witenoff was one of 26 law students nationwide selected by the American Constitution Society as a Next Generation Leader. Students are selected for the honor based on their leadership qualities and engagement with ACS. Witenoff was president of the VLS chapter of the ACS and served as an ACS Communications Fellow in Washington, D.C., before law school.

Class of 2020

Micah Bradley receives Class of 2020 Founder’s Medal for First Honors

Micah N. Bradley of Brentwood, Tennessee, received the Founder’s Medal signifying first honors for the Class of 2020. Bradley also received the Robert F. Jackson Memorial Prize, awarded to the member of the second-year law class who maintained the highest scholastic average during the two years, and the Archie B. Martin Memorial Prize for Scholarship, awarded to the student of the first-year law class who earned the highest general average for the year.

She was senior en banc editor of the Vanderbilt Law Review and articles editor of the Environmental Law and Policy Annual Review. As a 2L, she was a Legal Writing teaching assistant.

Bradley is a law clerk for Judge Eli Richardson ’92 of the Middle District of Tennessee in 2020–21. She is the daughter of Lori Michelle Bradley (MS’90).

Amber Banks ’20 receives 2020 Equal Justice Works award

Amber Banks is one of eight law students honored by Equal Justice Works with its 2020 Regional Public Interest Award. Equal Justice Works is a national nonprofit organization that facilitates opportunities for lawyers and law students to engage in public service.

Banks was a Garrison Social Justice Scholar at Vanderbilt. She also was honored by her classmates with the Class of 2020 Philip G. Davidson Award, presented to the graduate “chosen by the Vanderbilt Bar Association Board of Governors, who is dedicated to the law and its problem-solving role in society, and who provides exemplary leadership in service to the law school and the greater community.”

2020 grads Joe Sandford and Willoe DeFuccio named Gideon’s Promise Fellows

Willoe DeFuccio and Joseph Sandford have entered practice as Gideon’s Promise Fellows through the organization’s Law School Partnership Project. Fellows selected for the three-year program are assigned to public defenders’ offices in areas where more lawyers are needed to serve indigent clients. DeFuccio joined the Mecklenburg Defenders in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Sandford joined the Knox County Public Defender’s Community Law Office in Knoxville, Tennessee.

A native of Pittstown, New Jersey, DeFuccio became interested in criminal justice when she volunteered at a local juvenile justice facility as a freshman at the University of Richmond. She recalls being stunned to discover that juveniles received the same treatment as adult prisoners. “The juvenile correctional centers in Virginia operated like adult jails,” she said. “The residents would come in shackles.” She cites her Actual Innocence class with Professor Terry Maroney and her Mental Health Law class with Professor Christopher Slobogin as particularly impactful.

Sandford also entered law school intent on working as a public defender. “Everybody is entitled to a full and fair hearing in court no matter where they come from,” he said.

A native of Princeton, New Jersey, who earned his undergraduate degree at Syracuse University, Sandford worked at the Office of the Federal Defender for the Middle District of Tennessee in summer 2018 and at the Knox County Public Defender’s Office in summer 2019. “The leadership, dedication and camaraderie within the Knox County Public Defender’s Community Law Office was inspiring,” he said. “I knew this was an office where I would be supported as I embark on a career in indigent defense.”

2021 Bass Berry & Sims Moot Court winners

Ashton Andrews ’22 and Emily Gray ’22 won the 2021 Bass Berry & Sims Moot Court Competition Feb. 5, receiving the John A. Cortner Award and a cash prize. Andrews and Gray faced finalists Aaron Bernard ’22 and Emily Webb SUBMITTED ’22. The competition began in fall 2020 with 42 teams and 84 participants. Emily Detiveaux ’22 received the award for Best Oralist, and the team of Peter Byrne ’22 (BA '18) and Caylyn Harvey ’22 received the award for Best Brief.

Under the leadership of Moot Court Chief Justice Kareim Oliphant ’21, Executive Justice Chandler Ray ’21 managed a team of third-year students who organized and ran the competition. The problem, which addressed First and Second Amendment rights, was written by executive problem editor Taylor Daniel ’21 and associate problem editors Austin Maffei ’21 and Stefan Berthelsen ’21.

The competition’s final round was judged by Judge Carl E. Stewart of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, Judge Michael Y. Skudder of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, and Judge Elizabeth L. Branch of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit.

Hannah Miller welcomes a challenge—whether it’s leading route reconnaissance and convoy security missions, participating in multinational military training exercises, or preparing to serve in the U.S. Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

After earning her undergraduate degree at Princeton University, where she was student commander of the ROTC program, Miller was commissioned as an army officer. “I thought of nothing more challenging than having just graduated from college and being in charge of 43 people with wildly different experiences and backgrounds,” she said. “It sounded like such an exciting yet daunting experience, and it was not only a way for me to serve my country, but also to challenge myself.”

Miller was a platoon leader, executive officer and battalion staff officer in an army military police unit stationed in Grafenwoehr, Germany. Working with foreign military and police forces, she traveled across Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Ukraine.

The intellectual rigor of the JAG Corps inspired Miller, still an active-duty captain, to apply to the army’s Funded Legal Education Program. Miller’s husband, an infantry company commander stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, played a part in her choosing Vanderbilt. “I knew Vanderbilt punched above weight for its law program, but I also wanted to attend because of the university’s proximity to a military base,” she said.

She appreciates the mentorship she’s received from professors such as Professor of the Practice of Law Michael A. Newton, who also earned his law degree as an army officer. “Professors here go out of their way to take students under their wing,” Miller said. Her education was aided by the Thomas W. Beasley Endowment Fund, which supports VLS students who are military veterans or in service.

Miller is working in the Army’s JAG Corps and plans to clerk for Judge Amul Thapar of the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2023. “The U.S. military is a fighting force that believes in operating with fundamental respect for the rule of law, and I want to be a part of that,” she said. “I also look forward to the opportunity to practice all types of law—from assisting soldiers with individual legal needs, to prosecuting criminal cases, to advising commanders in the heat of things.”

JOHN RUSSELL

As Vanderbilt’s 2020 George Barrett Social Justice Fellow, Funmi Akinnawonu represents undocumented immigrants as an attorney at the Mississippi Center for Justice. Akinnawonu became aware of the need for legal services supporting immigrants at MCJ while working at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Jackson in summer 2019, after immigration authorities arrested and detained 680 undocumented workers at seven poultry plants in Mississippi on the first day of school, leaving many children with no adult at home.

“Some individuals were quickly released, but some remained in detention for months,” Akinnawonu recalled. “I saw lawyers coming together to represent these immigrants, and the Mississippi Center for Justice was coordinating the work of legal groups and pro bono attorneys. I will focus on individuals with criminal convictions or charges because they are less likely to find outside representation from other legal nonprofits.”

Akinnawonu feels well-prepared to start work representing immigration clients. Her parents immigrated to the United Kingdom, where she was born, from Nigeria, and later immigrated to the United States, settling on Long Island, New York. They became naturalized U.S. citizens in 2013. “As a child I watched my father navigating the immigration process and found it very interesting,” she said.

The fellowship is provided through the George Barrett Social Justice Program, which was endowed by Darren Robbins ’93 in honor of his friend and mentor, the nationally renowned civil rights lawyer George E. Barrett ’57.

106 VLS students worked pro bono for judges, government agencies and law offices, and nonprofits in summer 2020. Students received either school-funded stipend support or course credit for their work in unpaid legal positions in 26 states, the District of Columbia, and three foreign nations, including the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Ireland. They worked as legal interns with federal and state government agencies and judicial chambers, for attorneys general, district attorneys and public defenders, in state and municipal legal offices, with public interest and advocacy organizations, and in corporate legal offices. “Every summer, our stipend funds enable Vanderbilt Law students to gain practical legal experience by doing unpaid work in judicial chambers and law offices throughout the country and abroad,” said Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs Susan Kay ’79.

Faculty in the News

Sara Mayeux’s new book chronicles history of public defenders

Legal historian Sara Mayeux’s recently published book, Free Justice: A History of the Public Defender in Twentieth-Century America, chronicles the national debate over public defenders, starting with the establishment of the first public defender’s office in Los Angeles County in 1914.

Mayeux discovered that public defender’s offices, as government-funded agencies that provide lawyers for indigent criminal defendants, have a surprisingly contentious history. “The standard story you hear is that lawyers are committed to the right to counsel for indigent criminal defendants, and the reason defendants often don’t have access to effective counsel is because politicians and voters don’t understand this right and won’t provide adequate funding,” Mayeux said. “But historically, the legal profession was divided for a long time about how to provide counsel for indigent criminal defendants.”

In the early 20th century, lawyers immersed in a culture of private practice were often ambivalent about public funding for criminal defense or setting up government-operated defenders’ offices. By 1963, when the Supreme Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that any citizen charged with a crime had the constitutional right to legal counsel, lawyers had become more open to public funding for indigent defense, but most still saw private practice as the default model. “The legal profession has been good at giving lip service to the ideals of criminal legal representation for indigent clients, but not as successful at putting those ideals into action,” she said.

Free Justice traces the development of public defender reform proposals starting in the 1910s and 1920s, when several California counties established the nation’s first public defender's offices. But in other parts of the country, particularly on the East Coast, elite corporate lawyers remained convinced that the legal profession should remain independent from the government and sought to establish private organizations, sometimes known as “voluntary defenders,” to provide lawyers for indigent criminal defendants without depending on public funding.

However, Mayeux found, the private approach proved unsustainable. “By the 1960s, when the Court decided Gideon v. Wainwright, most lawyers embraced public funding for indigent defense, at least in theory,” Mayeux said. “But actually securing public funding was challenging.” This complex history resulted in an uneven patchwork of funding sources and institutional arrangements for indigent defense, a pattern that has persisted to the present day. “I heard a lot about the indigent defense crisis when I was in law school, and you still hear about it today,” she said. “The word ‘crisis’ implies a problem that has suddenly become acute and needs an urgent fix. But the language of ‘crisis’ has been a permanent feature of discussions of indigent defense ever since Gideon enshrined the constitutional right to counsel.

“We need to have a deep conversation about what criminal courts are supposed to do and whether equal justice would require structural changes to the legal profession itself. But, historically, there hasn’t been much interest in having that conversation,” she said.

SANDY CAMPBELL

2020 Hall-Hartman Outstanding Teaching Award winners: Chris Serkin, Dan Sharfstein, Kevin Stack, Yesha Yadav, Ingrid Wuerth and Debra Lee

The Hall-Hartman Awards are a long-standing Vanderbilt tradition recognizing faculty whose teaching is deemed outstanding in each first-year student section and for large and small upper-level elective courses. The awards are named in honor of former professors Donald J. Hall and Paul Hartman, both of whom spent their academic careers at Vanderbilt and were revered for their teaching.

“These awards are hard to win because we have so many outstanding teachers on our faculty, so they are coveted,” Dean Chris Guthrie said. “Professors cherish this recognition because it comes directly from the students they’ve taught this year.”

Stack, Serkin and Sharfstein were recognized for first-year teaching by each of the three 1L sections. Yadav and Wuerth were recognized for upper-level teaching, and Lee as outstanding adjunct professor.

Serkin

Yadav Sharfstien

Wuerth Stack

Lee

Samar Ali ’06 (BA’03) joins VU faculty as research professor

Samar S. Ali has joined the faculty of Vanderbilt University as a research professor of political science and law. Ali is on leave of absence from her legal practice at Bass Berry & Sims in Nashville while serving on the Vanderbilt faculty. She will co-direct the Vanderbilt Project on Unity and American Democracy with Jon Meacham, who holds the Carolyn T. and Robert M. Rogers Chair in American Presidency, and John Geer, Ginny and Conner Searcy Dean of the College of Arts and Science.

Ali’s impressive resume includes serving as a law clerk to Judge Gilbert S. Merritt Jr. ’60 of the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals and for Justice Edwin Cameron on the Constitutional Court of South Africa; a year as a White House Fellow in President Barack Obama’s administration; and as the state of Tennessee’s assistant commissioner of international affairs under former Gov. Bill Haslam. She was a co-founder of the Lodestone Advisory Group, a boutique consulting firm that specializes in growth strategies through innovation, venture capital, global markets and transformation, and recently co-founded Millions of Conversations, a nonprofit organization that aims to unite Americans around common values by fostering dialogue among those who hold different opinions, views or beliefs. She is a Young Global Leader with the World Economic Forum, a term member with the Council on Foreign Relations, a Winrock International board member, and a recipient of the White House Fellows IMPACT Award. She is an adviser to the Aspen Institute’s initiative “Who Is Us: A Project on American Identity,” and is a New Pluralist Fellow.

Ali has taught on Vanderbilt’s adjunct law faculty, serves on the law school’s Board of Advisors and has received the university’s Young Professional Achievement Award.

Rossi and Serkin win 2020 Morrison Prize for sustainability scholarship

Jim Rossi and Christopher Serkin received the 2020 Morrison Prize for best scholarship in environmental law with their co-authored paper “Energy Exactions,” published in the Cornell Law Review.

Rossi

Rossi holds the Judge D.L. Lansden Chair in Law and serves as associate dean for research; Serkin holds the Elisabeth H. and Granville S. Ridley Jr. Chair in Law and serves as associate dean for academic affairs. Both are affiliated with the Energy, Environment and Land Use Program at Vanderbilt Law School.

Their paper proposes that the use of “exactions”—fees or other requirements routinely imposed by local governments on real estate developers to ensure they bear all or a portion of the cost burdens their development projects place on schools, roads, water and other local services—be extended to include the cost of the additional energy burden each new real estate project creates.

“This is one essential type of cost burden that is seldom accounted for up front,” Rossi said. “That’s a missed opportunity in several ways, including planning for sustainable energy.”

“We propose that local municipalities could use exactions to hold real estate developers more accountable for their impacts on the electricity system,” Serkin said. “Municipal governments and developers are both familiar with exactions; expanding their use to include their impact on the energy infrastructure is both practical and fair.”

Rossi and Serkin argue that energy exactions could be a powerful tool to encourage developers to incorporate energy-saving technologies, rooftop solar and other sustainable energy strategies into new projects. Adding such requirements to the land-use permitting process, they write, also would improve long-term planning by changing a system that relies on state regulators and private utilities to make most decisions governing energy demand into a process that directly involves local governments and real estate developers.

Local energy exactions also could produce valuable information about energy demand, diversify risks in infrastructure investment, and encourage intergovernmental competition to promote grid reliability and carbon reduction, they argue, resulting in significant improvement over conventional state utilityplanning and rate-setting.

“Energy Exactions” is the second work by a pair of Vanderbilt scholars to receive the Morrison Prize since the competition began in 2015. In 2017, Michael Vandenbergh, who holds a David Daniels Allen Distinguished Chair of Law, and Jonathan Gilligan, associate professor of earth and environmental sciences, won the prize for their book Beyond Gridlock, which addressed the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the private sector.

Slobogin honored with VU’s Harvie Branscomb award

Christopher Slobogin was honored with Vanderbilt University’s 2020 Harvie Branscomb Distinguished Professor Award. The award, established in 1963 to pay tribute to Vanderbilt’s fourth chancellor, recognizes one member of the Vanderbilt faculty each year for creative research and teaching and service to students, colleagues and society at large.

Slobogin holds a Milton R. Underwood Chair in Law, directs the Criminal Justice Program and serves as an affiliate professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt School of Medicine. He has taken a leadership role in drafting model statutes to govern policing, in addressing issues of mental disability and the death penalty, and in advocating for protection of privacy in the modern age. Slobogin has served as reporter for three American Bar Association task forces addressing law enforcement and technology, the insanity defense and mental disability and the death penalty. He chaired the ABA’s task force charged with revising the Criminal Justice Mental Health Standards and the ABA Death Penalty Moratorium Implementation Project’s Florida Assessment Team. He currently is an associate reporter for the American Law Institute’s Principles of Police Investigation Project.

SANDY CAMPBELL

Michael A. Newton, professor of the practice of law, has been named to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, an independent agency that advises the president and Congress on domestic and international Arctic research through its recommendations and reports. Newton is one of eight commissioners tasked with establishing national policy, priorities and goals for scientific research related to the Arctic region. He works with other commissioners and agency staff to develop and recommend national Arctic research policy, implement the federal plan for basic and applied scientific research programs, and advise the president, Congress and government agencies.

Newton is an expert on the law of the sea, human rights law, national security, transnational justice and issues related to conduct of hostilities. Before entering the legal academy, he served in the U.S. Army for more than 21 years. At Vanderbilt, he developed and teaches the innovative International Law Practice Lab.

Sitaraman named an ACUS public member

Ganesh Sitaraman was named a public member of the Administrative Conference of the United States, becoming one of 40 ACUS members selected from the private sector. Sitaraman directs the Program on Law and Government. His current research addresses issues in constitutional, administrative and foreign relations law. ACUS members include experts across legal, business, nonprofit and academic arenas who recommend improvements to federal government regulatory and administrative processes. Sitaraman is the second public member appointed to the ACUS from the Vanderbilt Law faculty. Kevin Stack, who holds the Lee S. and Charles A. Speir Chair in Law, was named a public member in 2018.

Sitaraman also was elected a member of the American Law Institute. ALI is the leading independent organization in the United States producing scholarly work to clarify, modernize and otherwise improve the law. He is the author, most recently, of The Great Democracy: How to Fix Our Politics, Unrig the Economy, and Unite America (Basic Books, 2019).

Clarke wins Dukeminier Prize for journal article

“They, Them and Theirs,” a 2019 Harvard Law Review article by Jessica Clarke, received a 2020 Dukeminier Prize from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law. Clarke is the FedEx Research Professor and co-directs the Social Justice Program. Clarke’s article is one of four articles published in the 2018–19 academic year recognized with a prestigious Dukeminier Award. “They, Them and Theirs” is Clarke’s second article to be published in the Dukeminier Awards Journal and recognized with the Michael Cunningham Prize; her Duke Law Journal article “Inferring Desire” received the prize in 2015. In “They, Them and Theirs,” Clarke explores a legal frontier—the treatment of individuals with nonbinary gender identities—from a practical standpoint. “People with nonbinary gender identities do not exclusively identify as men or women, but most cases addressing transgender rights involve plaintiffs seeking recognition as men or women,” she explained. “My article asks what the law would look like if it took nonbinary gender seriously.”

Blumstein

Blumstein and Yadav appointed to Civil Rights Advisory Committee

James F. Blumstein and Yesha Yadav have been appointed to four-year terms on the Tennessee Advisory Committee of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Blumstein has served four terms on the committee, including two as chair; Yadav is serving her second consecutive term.

Blumstein is the University Professor of Constitutional Law and Health Law and Policy, professor of management at Owen Graduate School of Management and director of the Vanderbilt Health Policy Center. A renowned expert in constitutional law, he ranks among the nation’s most prominent scholars of health law, law and medicine, and voting rights.

Yadav is the Robert Belton Director and Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity and Community at the law school, where she also is a Chancellor Faculty Fellow and faculty co-director of the LL.M. Program. She worked on a major report released by the committee last year on legal financial obligations, addressing penal debt. The report sounded an alarm about the widespread use of legal financial obligation as a means of directly funding the Tennessee criminal justice system, cautioning that such funding methods may have unintended negative consequences that are contrary to the important state policies of promoting the successful reintegration of formerly incarcerated individuals and ensuring a just, fair and equitable criminal justice system in Tennessee.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, bipartisan, fact-finding federal agency whose mission is to inform the development of national civil rights policy and enhance enforcement of federal civil rights laws.

SANDY CAMPBELL

Ricks selected as Chancellor Faculty Fellow

Morgan Ricks was one of 10 faculty members from across the university selected for the 2020 cohort of Vanderbilt University Chancellor Faculty Fellows. Ricks, who studies financial regulation, is the law school’s current Enterprise Scholar. He joined Vanderbilt’s law faculty in 2012 after serving from 2009 to 2010 as a senior policy adviser and financial restructuring expert at the U.S. Treasury Department, where he focused primarily on financial stability initiatives and capital markets policy. His book The Money Problem: Rethinking Financial Regulation was published in 2016 by the University of Chicago Press.

Ricks testified before the House Financial Services Committee in June 2020 as part of a panel that also included former Commodity Futures Trading Commission Chairman Christopher Giancarlo ’84. They delivered their testimony during a virtual hearing on the topic of inclusive banking held by the committee’s Task Force on Financial Technology, which explored options for distributing stimulus benefits during the economic shutdown created by the COVID-19 pandemic to low-income individuals and small businesses with no bank accounts.

SANDY CAMPBELL

2020 Cecil Sims Lecture: Justice Neil M. Gorsuch

During a wide-ranging conversation with Professor Tim Meyer on Nov. 10, Justice Neil M. Gorsuch of the U.S. Supreme Court discussed the differences between serving as a federal appellate judge and a Supreme Court justice, his judicial philosophy, the importance of an impartial justice system, and how the Supreme Court decides which cases to hear.

The discussion, held via Zoom conference due to the pandemic, was part of the Cecil Sims Lecture Series, established in 1972 to “bring to Vanderbilt Law School distinguished men and women with extensive legal experience to associate informally with faculty and students.” Justice Gorsuch is the ninth Supreme Court justice to speak at VLS through the series, which also has hosted six attorneys general.

Gorsuch emphasized the courts’ important, long-standing role as an impartial arbiter of legal disputes. “I’ve been a lawyer and a judge for a long time,” he said. “As a lawyer, all I wanted was a fair shake for my client, and I felt like I was playing by rules that were fair, known in advance and would be followed. I came to have great respect for members of the judiciary. They became friends as well as heroes.”

When appointed to a seat on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, Gorsuch joined a small cadre of 180 federal appellate judges nationwide, handled a diverse range of appeals from district courts in Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Utah, and served with judges appointed by presidents from Lyndon Johnson to Barack Obama. The cases that reached the appeals court were the hard cases, he said, emphasizing that judges with diverse backgrounds and perspectives nevertheless usually reached unanimous decisions. “Who the president was and who appointed the judge had very little to do with the disposition of cases,” he said.

Justice Gorsuch ended his discussion by urging students in the audience to consider judicial clerkships. “I think you’ll find the opportunity early in your career will change your life and enrich it in ways that are very difficult to foresee,” he said. “You’re likely to get a lot more experience than you would in other settings. I don’t think there’s a better investment, at any age, in yourself. Not only is the experience instrumentally useful, but it’s extremely valuable.”

The Cecil Sims Lecture Series honors Cecil Sims, a 1914 first-honor graduate of Vanderbilt Law School and a founding member of the Nashville-based firm of Bass, Berry & Sims.

SUBMITTED

2021 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Lecture: Judge Carlton W. Reeves

Judge Carlton W. Reeves of the Southern District of Mississippi delivered the 2021 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Lecture on Jan. 26 via Zoom. Judge Reeves’ talk addressed how King’s legacy should inform the response to the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. “King would not have been surprised at violence against democracy,” he said, adding that King also would urge Americans to “indict the system that spurred fear and violence.” Judge Reeves was appointed to the federal bench by President Barack Obama in 2010. He was the first person in his family to attend a four-year college. He entered legal practice as a staff attorney for the Supreme Court of Mississippi after earning his law degree at the University of Virginia and serving as a law clerk for Justice Reuben V. Anderson of the Mississippi Supreme Court.

Isiah Franklin had faced his share of uphill battles. Among the more grueling were the ones that involved an actual hill outside his high school in Huntsville, Alabama. During wrestling season, his coach, Chris Scribner ’20, would shout encouragement as Franklin and his teammates ran drills up the grassy slope, taking turns carrying each other piggyback until their knees wobbled from fatigue.

But as difficult as it was for the wrestlers to prepare for the physical rigors of competition, Scribner found it equally daunting to teach basic wrestling skills to a team of boys whose familiarity with the sport was limited to the outlandish professional wrestling matches on television.

At the insistence of his principal, Scribner had started the wrestling program at J.O. Johnson

High School by gathering a group of boys,

Franklin included. He knew that, to compete against the best in the state, the novice wrestlers had to conquer a steep learning curve.

Franklin recalls learning a valuable lesson from wrestling: not to give in to the grip of adversity. In matches where he found himself locked in a struggle, the instructions Scribner shouted across the mat were his lifeline.

Sometimes Scribner advised him on technique, suggesting ways to adjust his position to gain leverage on his opponent. Sometimes he simply urged Franklin to dig in his heels and keep fighting.

Scribner’s coaching and encouragement worked. Franklin went from a lanky freshman who knew almost nothing about wrestling to placing third in his weight division at the Alabama state championships his senior year. His drive and commitment carried over to the classroom too. Despite the odds stacked against him, Franklin graduated from high school and was accepted to Vanderbilt. “When Isiah called to tell me he’d been accepted to Vanderbilt, I was in the airport and just started crying. I actually missed my flight,” Scribner recalled.

Scribner had come to Johnson in 2013 through the Teach for America program, which recruits recent college graduates to teach at low-income schools. The remarkable story of the wrestling program he started at Johnson became the subject of an awardwinning documentary, Wrestle, that aired on PBS’s Independent Lens in 2019. The film follows Franklin and three other promising wrestlers as they struggle—at home, at school, on the mat—through a single season of their newfound sport.

But what the film doesn’t touch on—and what makes the story even more extraordinary—is how Scribner’s work at Johnson spawned a nonprofit, the CAP and GOWN Project, which provides underrepresented Huntsville high school students opportunities to tour college campuses, improve their ACT scores and engage in STEM education. CAP and GOWN is the reason Franklin applied to Vanderbilt. It’s also why Scribner continued to make the 200-mile round trip to Huntsville each week throughout law school. Although he was no longer employed as a teacher and coach at Johnson, the community on Huntsville’s north side always will be a second home to him. And if the bond he shares with Franklin is any indication, there likewise will always be a place in Scribner’s life for the students he helped mentor.

Going to the MAT

In many ways there couldn’t be a starker contrast between Scribner and the students he taught and coached at Johnson. For one, he’s from New York City—a place far removed from Huntsville, geographically and culturally. His wrestling team members had known hardship and disappointment from an early age, a stark contrast to Scribner’s privileged upbringing.

But Scribner also knows from personal experience just how precarious one’s teenage years can be. After developing a substance abuse problem in high school, he nearly squandered every advantage afforded him. The documentary includes a moving scene in which Scribner details his own struggles to a student battling drug addiction. “I got kicked out of high school for continuing to drink and take drugs despite many interventions,” Scribner said. “I would make these sweeping proclamations that I was going to quit for good this time, and then two weeks later, two days later, two hours later, I’d find myself loaded on something.”

After completing a recovery program, Scribner earned a bachelor’s in English and a master’s in journalism at Georgetown University. Initially, he planned to pursue a career in Washington, D.C., and got a job in 2011 as a deputy press secretary for U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer, D–N.Y. But the 2012 mass shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, changed Scribner’s perspective. “It was frustrating to see nothing happen after the parents lobbied Congress for better gun control,” he said. “That’s when I decided to join Teach for America. I realized I could do more to positively impact people’s lives as a teacher than I could as a congressional aide.”

Assigned to Johnson as a ninth-grade world history teacher, Scribner decided to volunteer as a coach. He ran track in college, so assisting the track team seemed a natural fit. But Roderick Tomlin, the school’s assistant principal, had something else in mind. “Mr. Tomlin had been an instructor at the Marines drill instructor school. He was literally a drill instructor for drill instructors,” Scribner recalled with a laugh. “I asked him if I could coach track, and he said no, but that I could coach wrestling instead. He’s an intimidating guy—you just say yes to whatever he says. So of course I said yes.”

What Scribner didn’t realize was that Johnson had no wrestling program. No one on staff had ever coached the sport. There was no equipment and no uniforms, nor was there a place for the team to practice. None of the students had any wrestling experience. Scribner had been a varsity wrestler in high school, so he at least knew what was needed to get the program off the ground. “Because I was a new teacher who wanted to make a positive impression, I told myself, ‘OK, let’s do this,’” he said. “And honestly, it was exciting because of all the pushback I got. The more obstacles there were, the more determined I became.”

Scribner began raising money for the team. Several fellow teachers and his family members offered financial support. He put bills that weren’t covered through these efforts on his personal credit card. He also staked claim to a storage area at Johnson, transforming it into the wrestling room. “It was this dark corner at the back of the school. There was no ventilation, no heat, no AC,” he recalled. “But we did have power, so there’s that.”

As many as 30 boys came to the tryouts that fall “thinking it would be like WWE wrestling,” Scribner recalled. As the reality and demands of the sport sank in, the team’s numbers dwindled. By the start of the season, the Johnson team had 14 wrestlers—the bare minimum needed to compete.

Franklin was an eighth grader when Scribner started the program, and he joined the team the following year. Like his predecessors, he had no inkling of what would be expected of him. “I was one of the worst wrestlers. It was horrible,” he remembered. “Coach Scribner got onto me about being soft, and I remember telling him that I was a lover, not a fighter.”

Scribner has similar memories of Franklin’s freshman year. “Isiah was one of the naturally least talented kids we ever had try out. He was so lanky and physically weak that I was legitimately scared whenever he’d wrestle,” Scribner said. “I wasn’t a law student yet, but I worried about liability.”

But Franklin knuckled down in the weight room and on the mat to transform himself into a formidable wrestler. During his sophomore year he was part of a team that capped its most successful season ever with an eighth-place finish at the state championships. By his junior year, he placed sixth in the state.

Franklin’s transformation wasn’t just physical. Wrestling helped him see beyond the bleak confines of his north Huntsville neighborhood to a broader world of possibilities, including becoming the first person in his family to attend college—an aim he might never have taken seriously had it not been for Scribner. “I gained a lot of humility and confidence through wrestling,” he said. “But it also provided me a sort of peace. I have a tattoo on my chest that says ‘SERENITY.’ I got it because of the serenity prayer we’d say after every practice.”

Campus Paths

The story of the Jaguars wrestling program is really a tale of two schools: J.O. Johnson, where Scribner launched the wrestling team, and the school that replaced it, Mae Jemison High School, named for the Alabama native who was the first African American woman in space. After Johnson was forced to close its doors in 2016 after years on the Alabama Department of Education’s “failing schools” list, Franklin and his classmates were assigned to Jemison. Starting Franklin’s junior year, the Johnson Jaguars became the Jemison Jaguars, and Scribner moved to Jemison to continue teaching and coaching wrestling.

While he and his fellow teachers hadn’t been able to save Johnson from shuttering, they had been doing everything possible to give their students a leg up. In 2014, Scribner and fellow teacher Emily Heller used surplus funds Scribner had raised for the wrestling team to organize a trip for Johnson students to tour Nashville college campuses. Their very first stop on that trip: Vanderbilt Law School, where a friend of Scribner’s, Eric Steinberg ’16 (MBA), had agreed to show the group around. “The point was to get the students stoked for college and just give them some purpose in high school,” Scribner said. “The trip made a big impression. The kids kept talking about it for months afterward.”

Scribner’s and Heller’s efforts evolved into a nonprofit, CAP and GOWN, which stands for Create Academic Pathways and Guide Others Wherever Needed, which has helped students from Johnson and Jemison visit more than 70 college campuses and helped increase the schools’ college matriculation rate by more than 600 percent.

Franklin went on several CAP and GOWN trips, including two to Nashville as a sophomore and a senior. The trips yielded plenty of memorable moments, including being among the 50-some-odd students invited into the small apartment of Alice Randall, the best-selling author and writer-in-residence in African American and diaspora studies. But what stands out to Franklin and Scribner about the second trip in particular is a fateful encounter with Suzanna Sherry, the Herman O. Loewenstein Professor of Law. By that time, Scribner was a first-year law student taking one of Sherry’s classes. Franklin sat in on it, and afterward Scribner introduced him to her.

“Isiah obviously had read and understood the material and had figured out for himself that some of the doctrine was internally inconsistent—which is more than some law students can do in their first semester,” she recalled. “I knew then that he was a special young man who was going to do great things with his life. I immediately talked to our dean of admissions here at the law school and asked him to convey to the undergraduate admissions people how impressed I was with Isiah.”

At Vanderbilt, Franklin faced another uphill battle: adapting to college life as a first-generation student. He admits that the transition wasn’t easy. “In the beginning it was a matter of feeling like the students around me had a lot of money and I didn’t,” Franklin said. “But eventually I became friends with many of them. That was the best part. Everybody I encountered is so different, but we all share the same hunger to succeed.”

Reflecting on his own Vanderbilt experience, Scribner said he appreciates how the law school community balances being “both competitive and yet friendly and tight-knit at the same time.” He also makes a point of mentioning two professors—Assistant Dean for Public Interest Spring Miller and Milton R. Underwood Professor of Law Chris Slobogin—for the impact their teaching had upon him. Slobogin’s insights on mental health law and criminal law have been of particular interest because Scribner has seen firsthand how closely the two are entwined in many of his students’ lives.

But if he had to single out one highlight of being at Vanderbilt, it would be the time he was able to spend with Franklin. Their friendship has now spanned three schools— Johnson, Jemison and Vanderbilt—and seems to have only gotten stronger. At Vanderbilt, Scribner looked out for Franklin like an older brother would, reminding him to check his email and buy allergy medicine, while taking care not to be too intrusive. “To be honest, the best part has been being able to attend the same school as Isiah,” Scribner said. “It’s probably the coolest thing that’s ever happened in my whole life.”

Chris Scribner has joined the U.S. Army JAG Corps and holds the rank of captain. Isiah Franklin plans to graduate from Vanderbilt in 2022.

A Sense of BELONGING

at Vanderbilt

The endowment of a permanent director of the Diversity, Equity and Community Office in honor of the late Professor Robert Belton enables VLS to build on its long-term commitment to diversity, inclusion and racial justice.

“My father truly enjoyed teaching at the law school, specifically the vigorous debates he had with students in and outside the classroom around equity. It’s an honor that the Diversity, Equity and Community directorship will bear his name, as that demonstrates the impact he had within the VLS community. My family looks forward to attending DEC lectures, and we thank the donors who made the endowed position possible.”

— Keith Belton

One evening in the fall of 1956, Fred Work ’59 received a warning phone call from his classmate Melvin Porter ’59. Work and Porter had just entered Vanderbilt Law School as the first two African American students admitted.* They had arrived on the first day of class to find white sheets of paper covered with black dots affixed to every tree leading to Kirkland Hall, where the law school was then located. “This was not a sign of welcome,” Work recalled in a 2007 interview.

Porter informed Work that a carload of white people was en route to his house. When Work’s doorbell rang 10 minutes later, he peered out the window to see his front porch crowded with white men. Work was wearing a pair of slacks and a robe. He considered not answering the door but then recalled that his family had an antique pistol. He tucked it into the pocket of his robe and opened the door. To his surprise, he was greeted by a wellintentioned group of Vanderbilt Law alumni. Embarrassed by negative articles about the law school’s integration that had appeared in local newspapers, the men wanted to assure Work and Porter that they were welcome at Vanderbilt Law School. “They had come to encourage us and offer to help us in any way they could,” Work said.

Work invited the visitors in. After they left, he exhaled and took the gun out of his robe to put it away. It went off, barely missing his foot. Work was living with his parents, who taught at Fisk University. “You can imagine what a commotion that caused,” he said.

Vanderbilt became the first Southern law school to integrate with the admission of Work and Porter in 1956.* But both men recalled their first year at Vanderbilt as stressful. “The faculty were very helpful, and Dean [John] Wade was committed to the success of this process,” Work recalled. “But certainly some students—especially those in leadership positions—could have been more instrumental in making the atmosphere better.”

Making the atmosphere at Vanderbilt

better is one of many important goals of the law school’s Diversity, Equity and Community Office, formed last summer by Dean Chris Guthrie with support from faculty, students and staff. “Lawyers can bring about tangible progress toward building a more democratic, just and equal society,” Guthrie said. “We want

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY

to foster an atmosphere at VLS where people with diverse backgrounds, identities and perspectives all feel welcome and included and find opportunities to learn and contribute, and we want to educate lawyers who will bring that perspective to their work and communities wherever they live and practice.”

Placing the law school’s diversity and inclusion programs and initiatives under the oversight of a single office with a dedicated director was a key recommendation of three task forces of faculty, students and staff. Guthrie formed the groups last June after the deaths of several Black Americans as a result of police brutality and racial violence sparked a much-needed national conversation about systemic inequities in the criminal justice system. “I wanted to identify immediate actions and long-term initiatives we should take as a faculty, staff and student body to address racial inequities and injustices at the law school, in our community and beyond,” he said.

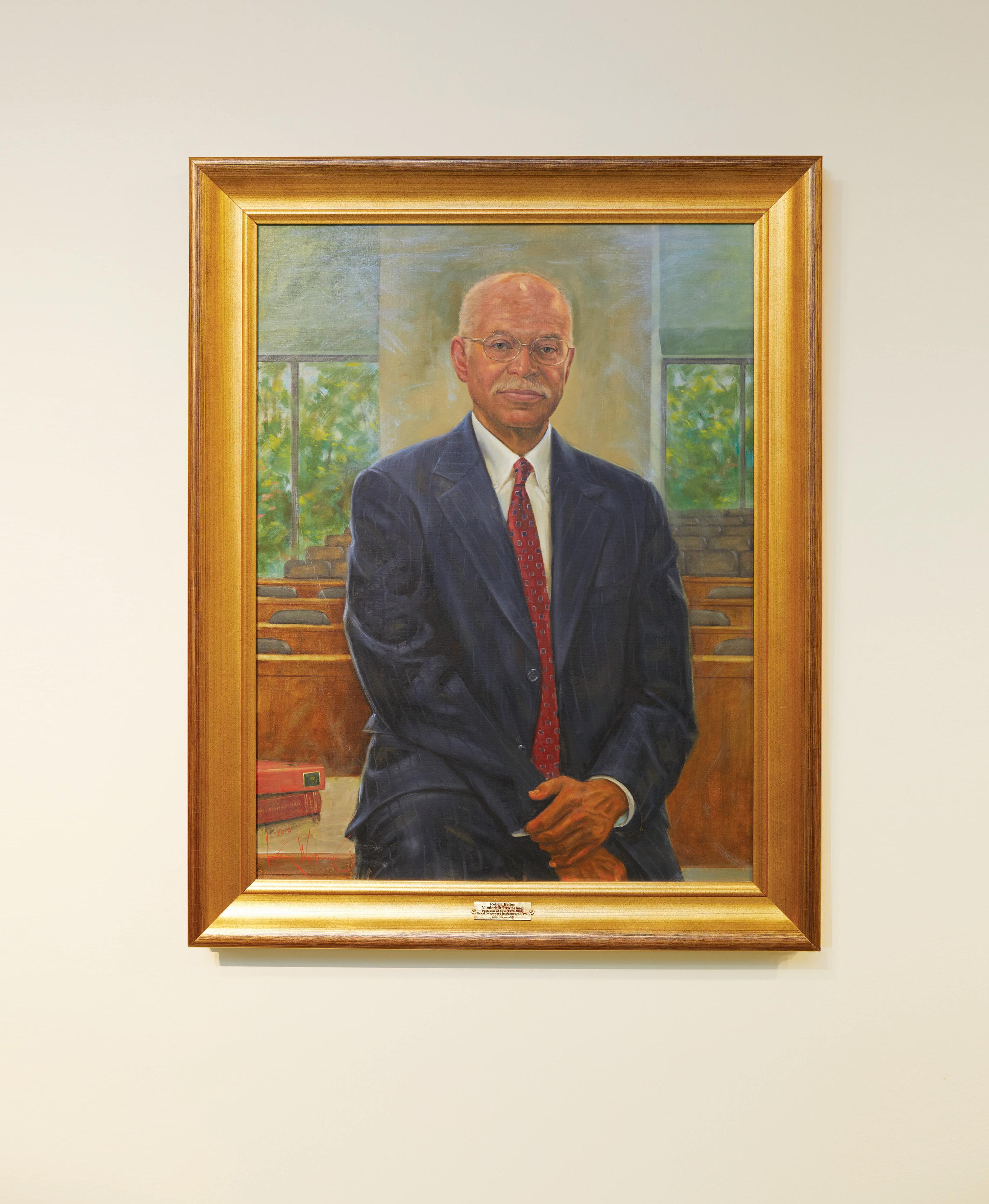

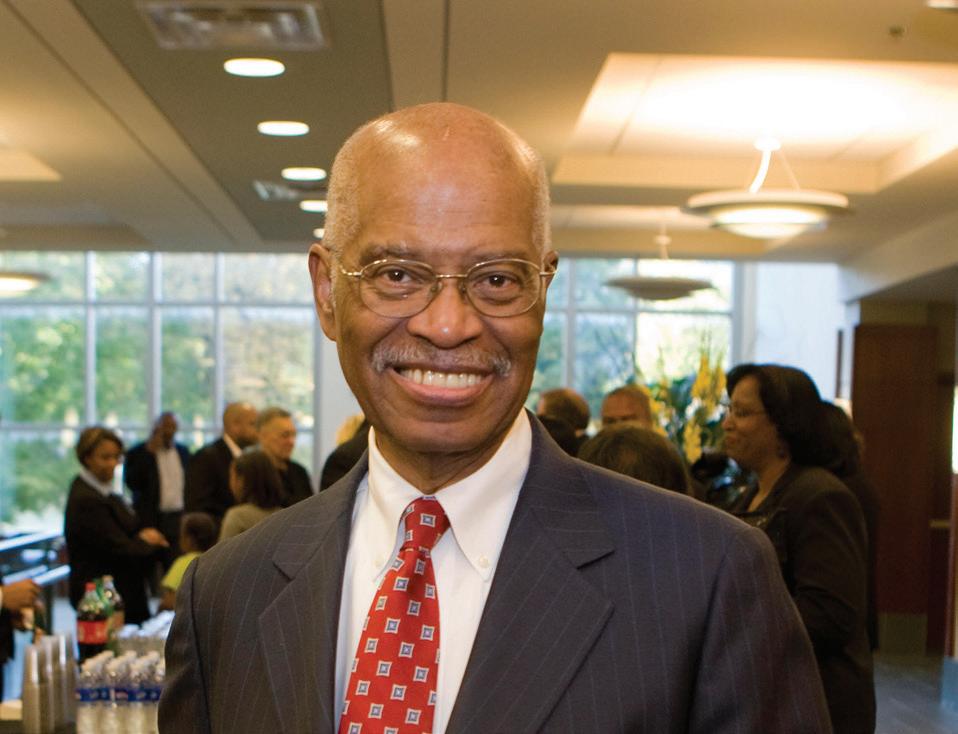

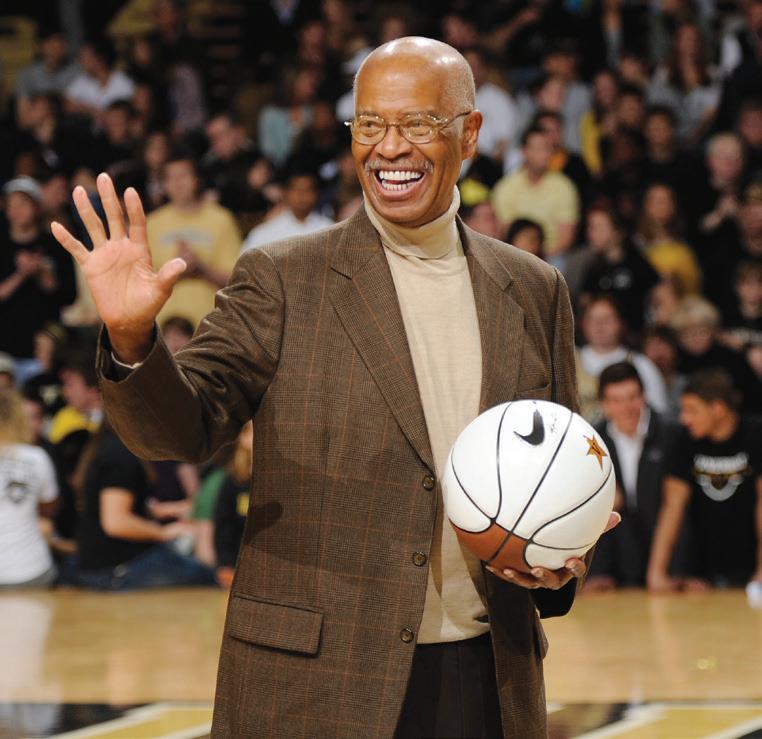

Anonymous donors soon stepped forward to endow a permanent position directing the new office in honor of the late Professor Robert Belton, who became the law school’s first Black tenured faculty member in 1982. Guthrie is excited about the opportunity to build on the law school’s history of supporting diversity and inclusion, which started with Wade’s decision to integrate the law school in 1955, almost a decade before Vanderbilt University admitted its first Black undergraduates. He also is gratified to see Belton’s legacy honored in such a meaningful way. “Bob Belton was a pioneering lawyer and employment law scholar who took very seriously his role as a mentor to our students,” Guthrie said. “By funding a permanent director of our Diversity, Equity and Community programs in his honor, two generous and thoughtful donors have anchored our program and solidified Bob’s legacy as a role model and teacher.”

Belton joined Vanderbilt’s law faculty in 1975

after 10 years of legal practice, and he taught for 35 years before retiring in 2009. His prior work included five years as a litigator with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, where he led a national civil rights litigation campaign to enforce a then-new federal law prohibiting employment discrimination based on race and sex. Belton played a major role in a landmark Supreme Court civil rights case decided in 1971; his book, The Crusade for Equality in the Workplace: The Griggs v. Duke Power Story, was published in 2014, two years after his death.

Like Fred Work and Melvin Porter, Belton understood the pressures of being a pioneer. He had practiced at one of the first integrated law firms in North Carolina after earning both of his degrees at two majority white universities in the Northeast in the early days of integration. His recollection of the isolation he and his fellow Black students felt while earning degrees at the University of Connecticut and Boston University School of Law motivated him to advocate for minority students and faculty at Vanderbilt.

As the first to hold the title of Robert Belton Director of Diversity, Equity and Community, Associate Dean Yesha Yadav

balances the weight of responsibility she feels for launching the office with her excitement about the office’s mission of building a more inclusive and anti-racist community in every area of law school life. She and Guthrie both emphasize that establishing a permanent office of Diversity, Equity and Community is a foundational step. “For me, the most important thing was how willing Dean Guthrie and the administration were to put resources, ideas and support behind this office and see it succeed and flourish at the law school,” Yadav said. “Since this is a brand-new office, it feels like a startup—one that means something incredibly important to me.”

Since her appointment last July, Yadav has worked with members of the law school’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Council, which is a group of student leaders, faculty and staff that Assistant Dean of Student Affairs Chris Meyers first assembled as an informal working group. “We have a unique culture that makes Vanderbilt different from other law schools,” Meyers said. “I thought, what if we all got together and explored how we could do a better job as an institution of ensuring the student experience of our culture is equally welcoming and inclusive for everyone?” Students found the meetings so valuable and productive they asked Meyers to make the EDI Council permanent; it’s now an advisory group of representatives from each of the law school’s nine affinity groups that works with faculty and staff on a variety of initiatives.

Yadav had served as the council’s first faculty adviser. When she accepted the appointment to head the new DEC office, she turned to Meyers and council members, including Black Law Students Association President Samantha Furman ’21, for help planning activities and initiatives the new DEC program could launch during the pandemic. By that time, it was midsummer, and both Furman and Yadav knew they were unlikely to be on campus in the fall. Furman had chosen to take her 3L classes remotely and Yadav to teach her classes on the Zoom platform. “Promoting unity and diversity is especially challenging when members of our community cannot meet in person,” Furman said.

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY

Belton taught at VLS for 35 years.

– Dean Chris Guthrie

Affinity Organizations

n Asian-Pacific American Law Student

Association n Black Law Students Association n Jewish Law Students Association n La Alianza n Law Students for Veterans Affairs n Middle Eastern Law Student

Association n OUTLaw n South Asian Law

Students Association n Women Law Students

Association

Willie Griggs filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of himself and 12 fellow African American employees against their employer, Duke Power Co., in 1970, in which he challenged the company’s “inside” transfer policy, which required employees who wanted to work in any department other than the lowest-paying Labor Department to have a high school education or achieve a minimum score on two standardized IQ tests. The requirements had been enacted after Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it illegal for employers to discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex or religion. While Duke Power had stopped restricting Black employees to the Labor Department, the new requirements effectively perpetuated the race-based discriminatory policies the company had previously used to relegate Black employees to jobs that paid substantially less than those in departments where only whites worked. A district court dismissed Griggs’ claim and the Court of Appeals found no discriminatory practices.

Robert Belton, who represented the plaintiffs for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, argued the case in lower court. In his book, The Crusade for Equality in the Workplace (University of Kansas Press, 2014), he gives a firsthand account of the battle to put civil rights law to work. On March 8, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled that a “disparate impact” test could apply to policies and practices that had the effect of limiting employment opportunities for Blacks.

When Belton died in 2012 after completing the book manuscript, legal historian Stephen L. Wasby edited the book for publication. “This book is the story Bob wanted to tell—about the Griggs case; about the Legal Defense Fund’s litigation campaign; about his colleagues at the LDF, … and about the law of equality in the workplace as it came into place in Griggs and other LDF cases and was maintained against the Supreme Court’s diminution of the LDF’s victories,” Wasby wrote in the book’s introduction. “This book is dedicated by Bob’s wife and children to his love of scholarly work.”

A Mentor for Life

Brian Winfrey ’06 found his career calling in Professor Robert Belton’s Employment Discrimination class

Brian Winfrey ’06 knew nothing about the field of employment law when he signed up for Professor Robert Belton’s Employment Discrimination law class as a 2L in fall 2004. “I signed up because he was one of the few Black tenured professors at Vanderbilt,” Winfrey recalled. “I wanted to take a class from a professor who looked like me.”

Winfrey soon realized he had found his calling. “Professor Belton showed me how the practice of law could be utilized to further social change for people who looked like me,” he said. “I knew if I practiced employment law, I could have an impact on future generations that I might not have in another practice area.”

Belton was an outstanding teacher. “The guy knew everything about employment law—he literally wrote our textbook,” Winfrey said. And he became Winfrey’s mentor for life. “I’d drop by his office every couple of weeks, and Professor Belton would share war stories about cases he’d worked on at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and in private practice, always over a glass of Jack Daniels, which was his personal favorite,” Winfrey said.

Winfrey especially appreciated Belton’s stories about how growing up in the rural, segregated South had sparked his interest in fighting for equal employment opportunities for African Americans. “His high school teachers in High Point, North Carolina, were accomplished Ph.D.’s who could not get jobs anywhere else because of their race,” Winfrey said.

With Belton’s encouragement, Winfrey applied for an internship at the Nashville office of the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission’s National Labor Relations Board the following semester. His work there confirmed his career choice. He joined Ogletree Deakins after graduation and then moved to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of the Solicitor, where he worked as a trial attorney before founding his own employee and plaintiff’s law firm in 2012. The Winfrey Firm merged with Morgan & Morgan, where Winfrey is now a member, in 2017.

Winfrey now has his own war stories to share. He is particularly proud of the significant victory he and his co-counsel, Kathryn Barnett ’92 and Jason Gichner ’02, won on behalf of their client Patsey Thomas and her co-workers in Thomas v. Marshall County Board of Education. Thomas was an African American professional who was first demoted and then forced out of her executive position with the Marshall County School District for speaking out about workplace inequities. The case dragged on for four years.

Thomas was ultimately awarded back pay and $500,000 in compensatory damages. But in an important way, her legal victory was priceless. “I felt like my dignity had been robbed by what happened,” she told a local newspaper reporter after the decision. “This verdict makes me believe that, in the end, truth and fairness will prevail.”

Winfrey had been concerned about trying an employment discrimination case involving Black plaintiffs before an all-white jury and tracks his decision to take the case to his discussions with Belton about Griggs V. Duke Power and how to examine the disparate impact of employment policies. “The jury we ended up with was entirely Caucasian, and the case went to trial immediately after the election of Donald Trump, at a time when rhetoric and racial divisiveness were moving at an uptick,” Winfrey said. “That case was one of the hardest but most satisfying of my legal career, and at the end of the day, we saw that most people can see that wrongs still exist that need to be corrected.”

SUBMITTED

With student leaders and school administrators all pitching in to help launch DEC’s new initiatives during the pandemic, the new office has developed several new programs to foster education, conversation and mentorship across the Vanderbilt community. These include a Dean’s Lecture Series on Race and Discrimination, featuring the work of an interdisciplinary group of nationally recognized scholars in civil rights, racial justice and discrimination, including law professor Daniel Sharfstein; leading historians Kimberly Welch, Brandon Byrd and Rhonda Williams; education and public policy expert Matthew Shaw; and renowned psychiatrist Jonathan Metzl. The DEC also started a community-wide Book Club on Racial Justice and Civil Rights, which featured Professors Sara Mayeux, Jessica Clarke, Terry Maroney and Sharfstein leading thoughtful, provocative discussions of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, Dorothy E. Roberts’ Fatal Invention, Paul Butler’s Chokehold and Kenneth Mack’s Representing the Race.

Yadav also worked with the Career Services Office, the Alumni Office, the Vanderbilt Bar Association and the EDI Council to develop a DEC-sponsored Mentorship Program for Underrepresented Students designed to foster lifelong connections between alumni and current 2Ls and 3Ls. This fall, Meyers will launch another new program, 1Levate, to offer leadership training and mentoring to incoming 1L students from underrepresented communities. “1Levate is aimed at first-generation law students, who will be selected based on leadership potential,” he said. “The program will host a special orientation before regular student orientation and programming throughout the year, and students will be matched with a prominent local attorney who will mentor them throughout their 1L year.”

VLS has taken another action this year that

Furman considers crucial: Students are now more actively and systematically involved in the recruitment of new faculty and staff. They also work more closely with Admissions staff in recruiting students for incoming classes. “We’ve seen tangible results of our involvement with faculty and student recruiting, and we’ve been able to connect with prospective students directly,” Furman said.

Sickened by the video of George Floyd’s death last June, Furman and other members of BLSA’s executive board issued a statement asking the law school and the entire Vanderbilt community to stand in solidarity with students of color against police brutality and racism. “Everyone was unanimous about wanting to put out a statement—we felt it was our responsibility,” Furman recalled. “Any witness to that kind of murder would find it traumatizing, but to see it happen in the middle of the day in broad daylight felt like a total disregard for humanity.”

Vanderbilt’s BLSA chapter joined with BLSA chapters throughout the U.S. issuing similar statements articulating students’ anger and fear in the wake of Floyd’s death and the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade and Sean Reed at the hands of police officers; the fatal shooting of Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery by white residents of a South Georgia neighborhood who were arrested only months later after public outcry; and the death of Dallas resident Botham Jean, shot in his own apartment by an off-duty police officer. The VLS BLSA statement ended with a call to action: “We are calling on our classmates, faculty and the Vanderbilt University administration to stand with us in outwardly denouncing police brutality, white supremacy, and all forms of racial injustice by taking action.”

Guthrie was determined to respond with concrete actions aimed at effecting long-term change—a strategy he believes is hard-wired into the law school’s culture. He points out that 2021 marks the 65th anniversary of a Ford Foundation Grant that enabled the law school to establish the Race Relations Reporter, the first scholarly publication focusing exclusively on law related to race produced by a law school. Published from 1956 to 1972, the Reporter was initially funded by a $200,000 grant—a considerable amount at that time. “The Race Relations Law Reporter was established to present, in complete, objective fashion, the primary legal materials of the time dealing with the subject of race,” said former VLS Associate Dean Don Welch, whose history of Vanderbilt Law School was published in 2012. “It catapulted Vanderbilt onto the national scene. At one time, the Reporter had a circulation among legal periodicals second only to that of the Harvard Law Review.”

The late Ted Smedley, who joined Vanderbilt’s law faculty in 1957 as the Reporter’s faculty director, recalled that the initial grant had been for a two-year period. “They—and we!—had the idea that most of the problems would be solved in that time,” Smedley later recalled. “That seems a little humorous now.”

During the 16 years Vanderbilt published the Race Relations Reporter, the law school began admitting women in greater numbers and hired its first female tenure-track professor, Allaire Karzon, who received tenure in 1983, a year after Belton became Vanderbilt’s first Black tenured law professor. This spring, Vanderbilt Bar Association President Esther Lee ’21 worked with the EDI Council and the Women Law Students Association to organize a panel discussion addressing sexism in the legal profession and the difficulties women lawyers still experience in finding female mentors. “Law is still a maledominated profession,” Lee said. “We wanted to focus on building community for women in the law.”

Affinity groups such as the Women Law Students Association, formed in the mid-1970s, have helped underrepresented students adapt to law school and the legal profession. Since WLSA’s establishment,

VLS students have formed OUTLaw, which supports LGBTQ students, and groups that support students of many ethnicities and religious traditions. BLSA and OUTLaw member Miles Malbrough ’22 credits the national outcry over police brutality this summer as heightening awareness of the need to take concrete actions to promote diversity in all aspects of law school life. “Not all of the journals had a diversity component as part of their write-on process before last summer, and now they do,” Malbrough said. “This year student leaders were part of the interview process for faculty candidates, and we can now work with Admissions to help recruit a more diverse incoming class.”

The endowment of a permanent director for the law school’s Office of Diversity, Equity

and Community in honor of Robert Belton, Guthrie believes, cements the law school’s institutional commitment to diversity and inclusion. Going forward, the office will support Admissions, Student Affairs and other law school departments and will partner with the Social Justice, Public Interest, Criminal Justice and other academic programs to develop classes, research projects and opportunities for pro bono legal work designed to address systemic racial inequities and an inequitable criminal justice system.

“As lawyers, we aspire to uphold the rule of law, ensure equal treatment for all and protect individual rights,” Guthrie said. “Last summer we saw how far we are from those aspirations. Our goal as a law school and a profession is to close that gap.” n

Need-based scholarship endowed in honor of Janie Greenwood Harris ’64, Melvin Porter ’59 and Fred Work ’59

When Dean Chris Guthrie and Vice Provost Tracey George established a need-based scholarship in honor of the first African American graduates of Vanderbilt Law School, part of their purpose was to lead by example. The Harris, Porter and Work Scholarship will support students with a demonstrated commitment to civil rights; it is the second need-based scholarship that George and Guthrie have endowed at the law school. “We are committed to doing what we can to ensure that talented students, regardless of need, are able to study at our law school because we believe in the power of a Vanderbilt legal education to make a difference,” Guthrie said.

George and Guthrie also made a gift of $25,000 to support current student initiatives to address issues of racial injustice. “We wanted to endow a scholarship for its longer-term impact,” explained George. “But we also wanted to support current students seeking to implement projects and programs designed to make a difference today. We are excited to see what our students develop.”

The Harris, Porter and Work Scholarship recognizes Janie Greenwood Harris, the first African American woman to graduate from Vanderbilt Law School, and Edward Melvin Porter and Frederick Taylor Work Sr., who integrated the law school in 1956. “We have had the privilege of meeting Janie, Melvin and Fred,” Guthrie explained. “They excelled as students, enjoyed distinguished careers and were leaders in the legal profession and in their communities. We are in awe of their accomplishments and excited and humbled to be able to recognize them with a scholarship named in their honor.”

In addition to serving as vice provost for faculty affairs, George holds the Charles B. Cox III and Lucy D. Cox Family Chair in Law and Liberty. Guthrie has served as dean of Vanderbilt Law School since 2009.

Janie Greenwood Harris '64

Fred Work and Melvin Porter, Class of 1959, in front of Kirkland Hall, where they attended classes.

Adolpho Birch III '91 chairs VU Equity, Diversity and Inclusion committee