PROVENANCE II

NOUN mass noun

Pronunciation provenance/pr v( )n ns

Word forms: plural provenances

1 The place of origin or earliest known history of something.

1.1 The beginning of something’s existence; something’s origin.

1.2 (count noun) A record of ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity or quality.

Origin

Late 18 th-century: from French, from the verb provenir ‘come or stem from’, from Latin provenire, from pro- ‘forth’ + venire ‘come’.

provenance

a e e

PROVENANCE II

Tracing the History of Objects

EST. 1968

2

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, we produced our first provenance catalogue, due to the positive reactions and the pleasure we had in making it, we decided to make a sequel.

In this second Provenance catalogue we have focused on three groups of owners, all objects falling into one or more categories. Firstly the private collectors who have taken such great joy and pride in their collection, sometimes even adding personal labels to their pieces. The second group are scholars, who also published their knowledge and often collected or dealt themselves. Finally the third and last group are dealers like ourselves. Dedicated specialists in their field, who are all passionate about what they do; often determined to add scholarship to the objects before passing them on to a next owner. We feel privileged to be involved with beautiful objects on a daily basis, even though we are only the temporary owners. It can be saddening to see an object leave us, but joyful to see the happiness of the new owners and delighted when new objects arrive in their new home.

Researching the provenance of our objects can be interesting and rewarding. Sometimes the searches feel like wild goose chases, leading absolutely nowhere. Luckily on other occasions we can count on our knowledge, experience, archive, library and a measure of good instinct to trace back information on a previous owner of a piece. That is the advantage of having been in business for 55 years! Occasionally we buy on pure instinct, having a gut feeling knowing

there is more to discover than the object shows at first glance. That is where the adventure begins and when we can make a difference in the history of an object.

We hope you enjoy the individual stories of these 18 selected items, as we did researching and discovering the information round them.

Vanderven Oriental Art

The Netherlands

Tel. +31 (0)73 614 62 51 info@vanderven.com

www.vanderven.com

3

Floris & Nynke van der Ven

4

PROVENANCE: THE FINE ART DEALERS

Provenance is becoming increasingly important, for collector and dealer alike. Knowing where something has been and who the previous owner was, is not only informative and enjoyable; but it can also be a help in avoiding fakes - which have flooded the Chinese art market in recent years. That said, proven provenance will never fully replace the dealers informed eye, years of professional experience and intimate knowledge of the art market. But it can certainly be a useful tool, as well as fascinating to know who the former owner was of a piece - adding a very human dimension to the object.

When we talk about provenance, we actually also talk about the history of an object. Non-technical information about the piece, such as who was the owner and where was it located at a certain point in time. When art objects pass from one proprietor to the next, it is often through an intermediary such as a dealer or auction house; they in turn then also become part of the history of the object, adding to its provenance. This agency can be verified by invoices, certificates, photos, inventory notes, reports or dealer-labels – all placing that object to a certain place and time, occasionally even indicating what the value was at a certain point.

Long running art dealerships, like ourselves, often have fantastic records, archives and libraries – adding new information and scholarship to each piece we

deal with, before handing it on to its next owner. Older labels on objects then become an important form of provenance, many major dealers using a certain label at a given time – which can also be helpful with dates. Sadly sometimes labels have been removed, which makes research much harder or impossible. Invoices are also helpful when it comes to provenance, and we are particularly happy when a former Vanderven object comes back with its original invoice, certificate or TL report. Old photographs of the objects in a house interior, with or without family are a special bonus in terms of providing solid provenance – adding extra circumstantial information.

We therefore only highly recommend safely keeping all the paperwork that belongs to an object, preserving any labels on it and saving any family photographs showing the objects. This way we can all play our part in the provenance when we pass our treasures onto a next generation.

When we talk about provenance, we actually also talk about the history of an object

5

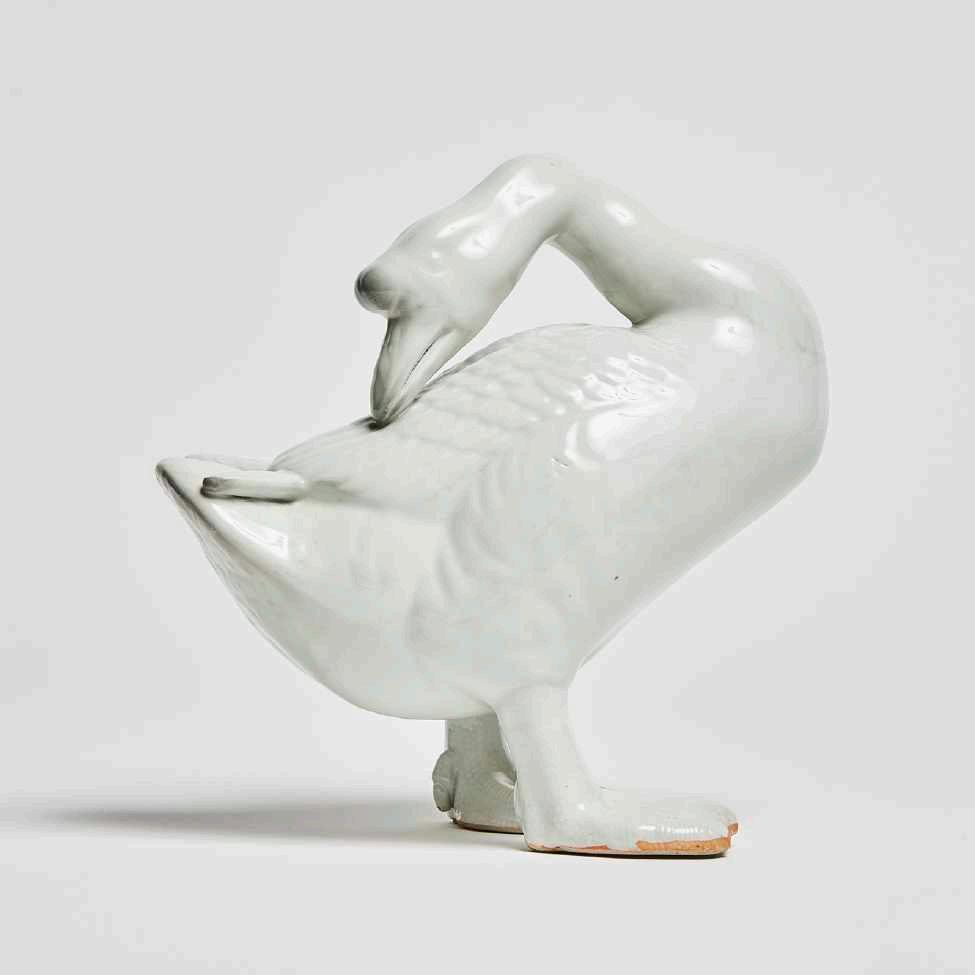

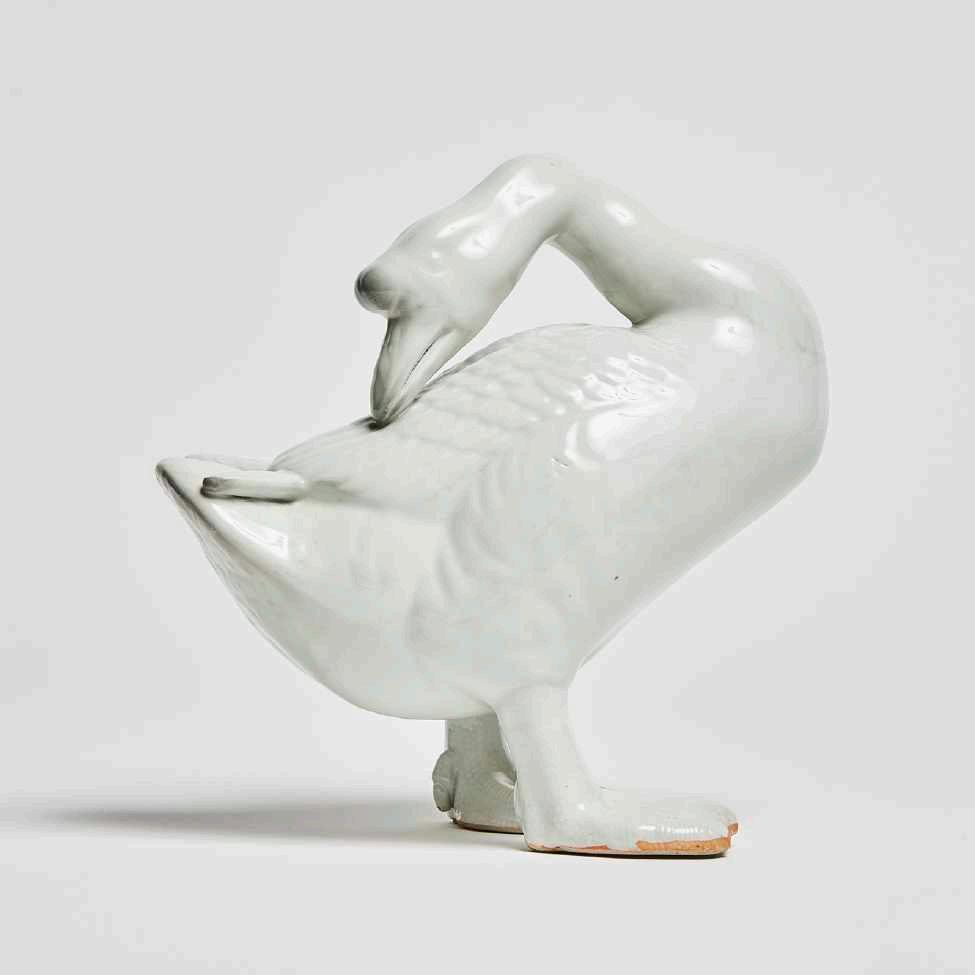

China, Qianlong Period (1736-1795)

Late 18th-century

H: 26.3 cm | W: 24.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Mottahedeh Collection, New York

With Vanderven & Vanderven, 1990 (invoice)

Rubel Collection, Germany 2023

PUBLISHED

Howard & Ayers, China for the West

LITERATURE

Cohen & Motley 2008, p.257 p.262 nr.18.3

Davids & Jellinek 2011, p.333

Howard & Ayers 1978, p.587 nr.611 & fig.611

London 1964, Lot 273

Pei 2004, p.90-91

Sargent 1991, p.258-259 nr.199

Welch 2008, p.74-75

Preening Goose

A very rare porcelain figure of a standing goose, with its head turned back preening its feathers. This model is robustly potted and glazed all over in a transparent light blue-grey. The bill, horny knob on its forehead and the underside of the tail feathers have a darker brownish grey colour. The plumage is moulded in relief, as is the pebbly skin on its broad webbed feet. On its underside, are two circular unglazed patches, where the supports were applied during firing. The underside of the feet are also unglazed. Production of such large models of birds, may have been inspired by the large animals being produced in the mid18th-century by Kändler at Meissen. It is possible that this goose once formed part of a pair, with an upright counterpart. This Goose was formerly in the Mottahedeh Collection and depicted in the important publication on Chinese Export wares China for the West.

The heavy legs and feet, as well as the horny knob on the bill, are characteristic of Chinese geese. The symbolic usage of geese in Chinese art, started as early as the Shou dynasty and lasted until the Qing dynasty. These birds are seen as benevolent, flying in groups so the young and healthy birds can help the weak or old. As migratory birds, geese fly away from the shadow (yin), following the sun (yang) to the south in the winter. For this reason they are an embodiment of Dao dualism: yin-yang, summer-winter, dark-light & male-female; this meaning would have greatly appealed to the Chinese literati. Geese are also considered romantic, symbolizing loyalty and marital happiness, flying in, forming pairs and mating for life. The Goose is also the emblem for the third and later fourth rank of civil officials, featuring on rank badges for mandarin robes.

1 |

6

7

Rafi & Mildred Mottahedeh were important collectors of Chinese export ceramics, ivories and jades. During their lifetime, they accumulated objects as they travelled around the world, their collection growing to around 2,000 pieces. Their passion was reflected in the ceramic wares produced by their company, Mottahedeh & Company, which specialised in reproducing dinner services with antique Chinese designs. Their formidable collection was largely dispersed when it was auctioned in 1985 and 2000.

An upright Goose, with a coloured beak and feet, is in the Copeland Collection at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem. A pair of Geese from the former Ionides Collection, were sold at Sotheby’s, London, 18 February 1964, lot 273.

8

9

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

H: 21.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Augustus The Strong, Dresden, (engraved nr.N:139 I)

With Jacques Van Goidsenhoven, Belgium 1968 (original certificate) Private Collection, Heverlee, Belgium 2023

LITERATURE

Goidsenhoven 1936

Jörg 2011, p.43 nr.33

Simonis 2018

Simonis 2020

Ströber 2001

2 | Dresden Bottle

A bottle with a spherical bulbous body and tall cylindrical neck. It is decorated with thick glossy famille verte enamels on a plain white body, with two large cavorting Fo dogs. One has a yellow body and head with a red tail; the other with a body and tail in green and an aubergine head, both have aubergine-coloured fur around their legs. Circling the mouth of the bottle, is a border of stylized lingzhi fungus (ju-i) in red and green. The underside of the bottle bears the distinctive blackened engraved number N:139 I, from the collection inventory of Augustus the Strong. The symbol ‘I’ denotes the category ‘Green Chinese porcelain’ under which both the famille verte and famille rose porcelains were classified.

Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony (1670 – 1733), amassed around 25,000 pieces of Chinese and Japanese porcelain; his agents scouring Europe to buy for the collection. Uniquely, several inventories of the Dresden porcelain collections were made during the 18th-century. The first was written during the lifetime of Augustus the Strong in 1721, the others were made after his death in 1735 and 1779. Each piece of porcelain was painstakingly recorded and engraved with an inventory number and symbol - now referred to as a palace number – ordering each object into a category. It is unclear how or when the bottle left the Dresden collection, from which many pieces were lost or sold over the years. Happily there are still over 8,000 pieces of porcelain in this significant collection.

Latterly the bottle was sold by Belgian scholar-dealer Jacques van Goidsenhoven to a private collector. Goidsenhoven wrote several key works on Chinese ceramics including La Céramique Chinois sous les Ts’ing 1644-1851 in 1936.

Identical bottles with the same number are also in the Porzellansammlung Dresden (inv.nr.PO3308 & PO4637). The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, also has a pair of bottles with the same decoration (inv.nr.38.765 & 6). The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge has a pair of a similar shape, but with differing decoration of rocks and flowers (inv.nr.OC.14A-1938). The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam has a much larger bottle with comparable decoration of cavorting Fo Dogs (inv.nr.Ak-RBK15882).

10

11

The bottle bears the distinctive blackened engraved number N:139 I, from the collection inventory of Augustus the Strong

12

13

AUGUSTUS THE STRONG

As Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, Augustus II was a fabulously wealthy ruler and a major patron of the arts. He was particularly partial to Oriental porcelains, of which by 1719 he had already amassed 19,000 pieces; the collection increased to a massive 23,000 recorded items by 1721 and 35,000 by 1735. Because of his megalomaniacal buying, Augustus was said to suffer from the maladiedeporcelainethe porcelain sickness.

Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland

Nicolas de Largillierre c.1715

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas

Augustus deployed agents across Germany and Europe to buy whatever they could lay their hands on – the bigger the items the better. The renowned fair in Leipzig was a good place for acquisition, as well as the trading ports where the goods arrived directly from the Far East. Amsterdam was a particularly rich sourcing ground, as here the newly made Chinese and Japanese porcelain was auctioned off directly by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) or sold by the private traders. The Netherlands also had a good number of dealers trading in older wares. There are also records of purchases from a Dutch female dealer living in Germany - Elisabeth de Bassetouche - who was at one point the court’s number one supplier of East Asian porcelain.

(1670–1733)

14

What makes the collection in Dresden particularly interesting – apart from its immense size - are surviving 18th-century written inventories. The first was undertaken in 1721-1729, each item in the collection was recorded and numbered – usually by etching the cyphers into the glaze. Occasionally numbers were drawn in ink over the glaze, and have now sometimes worn off. The inventories originally spanned over 1,000 pages, with the ceramics collection divided into ten chapters, six dealing with East Asian porcelain. A second and third inventory list of the porcelain were made in 1735 and 1770-1779. After the death of Augustus the Strong in 1733, the porcelain was packed away in the cellars of the unfinished Japanese Palace – which was being refurbished and enlarged especially to house the massive Oriental together with the Meissen collection.

Currently only around 8,000 pieces are still in the Dresden collection, the other pieces dispersed or lost over the years. A significant amount was sold during the famous auctions at Lepke’s in Berlin in 1919 & 1920; the collection director at that time wanted to sell the multiples to generate funds to fill in the perceived gaps in the collection. During the war, the collection was held safely in the mines around Dresden and later removed and taken away by the Russians – largely to be returned again in the East German communist era. After the German reunification, some pieces of porcelain were also restituted in a larger settlement with the previously exiled Prince & Princess von Sachsen (Wettin) from Moritzburg Castle.

The collection is a very important benchmark for dating Chinese porcelains, as all the pieces in the first inventory must have been produced in 1719 or earlier. There is currently a very important project underway, involving a panel of over 30 international experts, to photograph and publish this extraordinary resource. The project was launched to the public in January 2024.

15

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

Ø: 27.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Augustus The Strong, Dresden (engraved nr.N:49 I)

Collection Captain A.T. Warre, UK

Collection Mr. & Mrs. George Warre, UK

LITERATURE

Davids & Jellinek 2011, p.433-434 Jörg 2011, p.9-11 & nr.69

3 | Dresden Plates

A pair of porcelain plates, painted with overglaze enamels in the famille verte palette. The large circular central panel, within a double red line, is decorated with brightly coloured flowering boughs of peonies and magnolias growing around rockwork. Overhead are a pair of birds in flight and gold and iron-red insects flutter under half a gold sun. The wide rim has eight lobed cartouches in the reserve, with a yellow and aubergine double border; they contain four varieties of flowers including peony, prunus blossom, aster and lotus. The cartouches stand against alternating turquoise and iron-red liewen diaper ground. The reverse-back of the rim has three floral sprays, with green leaves and red flowers. The underside is decorated with two concentric circles in underglaze cobalt blue, one plate with a central artemisia leaf the other with a stylised archaic ding. They are both clearly incised and with the blackened inventory numbers N:49 I, corresponding to the collection inventory of Augustus the Strong, The symbol ‘I’ denotes the category ‘Green Chinese porcelain’.

Latterly these plates were in the collection of Captain Annesley Warre, a keen collector of Chinese ceramics, buying around 300 pieces from Bluett’s in London 1920 -1933. After his death in 1937 the pieces were inherited by his cousin George Warre and his wife, who passed them to their daughter. The collection eventually went on to be gifted to various museums or sold.

The engraved numbers on the porcelain and corresponding entries in the inventories, make the Dresden collection an invaluable research source, as all the pieces in it must date from before the inventory was made. The still substantial extant collection, of around 8000 pieces, has now been fully digitalised and made available online, after a gargantuan project realised by a host of international scholars. Inventory numbers from the collection, have in the past mistakenly been referred to as a ‘Johanneum marks’- a term referring to the Johanneum Palace in which the collection was briefly displayed.

The Porzellansammlung Dresden has a pair of very similar plates, one inventory number up N:50 I. They have the same border decoration, but a central panel with perching birds (PO3645 & 6703).

16

17

China, Early 18th-century, gilt-bronze mounts

18th/19th-century

H: 18 cm | W: 13.1 cm

PROVENANCE

King George V of England, c.1920 (label)

Private Collection, UK 2018

LITERATURE

Ayers 2016, Vol I p.91 fig.190-191,

Vol III p.1071

Bertoldi 2006, p.102 nr.57

Desroches 1976, p.40

London 1954

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1980, p.363 fig.371

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1989, p.252 fig.223

Sheaf & Kilburn 1988, p.156-157 pl.206

Royal Figures

Two figural groups of a conversing man and woman, glazed on the biscuit in blue and celadon enamels, with their hair picked out in black. In one group the smiling woman, who is turned towards the man, is wearing a shorter blue coat over a longer pleated white robe. The man, dressed in a celadon robe and black scholars hat, is holding a ruyi scepter in one hand and a book in the other. In the other group the man, also wearing a long celadon robe, is turning to look at the lady. One hand is behind his back and in the other he is holding a ritual baton (Hu). The lady wears a blue and celadon coat over a white robe. The faces, hands and feet are left unglazed. Both groups stand on unglazed biscuit bases and have gilt-bronze mounts.

The rare inventory label on one of the groups, has the cipher for George V (reigned 1910 – 1936). Similar known collection labels, have hand-written numbers on them, indicating in which the room in Buckingham Palace the item was located. Sadly, on this label that number has become illegible. The Palace inventory of 1914, which might be able to give more clarification, is now missing; so we can only speculate where these figures were displayed, or how they entered the Royal Collection. How they left the collection is also unknown.

Despite the George V label, the figural groups were probably not acquired by him. They may have entered the collection through his consort Queen Mary, who was a great enthusiast of oriental art - buying from the major dealers in London. However, such personal acquisitions would have been considered part of her private collection - which she documented in her catalogues of ‘bibelots’ - and were probably not labelled as palace inventory. It is therefore much more likely that the figures entered the Royal collection through George IV (17621830). He was an passionate collector of beautiful objects, including gilt-bronze mounted Chinese porcelains. He used them in lavish chinoiserie decorative schemes at Carlton House and Brighton Pavilion.

Similar single female figures are still in the Royal Collection (RCN 58837.1-2). Comparable figures in style and glaze were found in the Hatcher Cargo. A single male figure with a celadon glaze in the British Museum, London (Franks.198+).

4 |

18

19

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722), c. 1700

H: 43 cm

PROVENANCE

Prince de Beauvau Craon Collection, France 2017

LITERATURE

Ferguson 2016, p.35-37

Fuchs & Howard 2005, nr.104 & 105

Goidsenhoven 1936, p.122 & pl.19 nr.33

Kassel 1990, nr.62a-e.

Jörg & van Campen 1997, nr.90, 90a & 90b

Krahl & Ayers 1986, p.1003, fig.2132

Export Garniture

A five-piece garniture comprising of three ovoid covered jars and two beaker vases. They are decorated under the glaze in bright cobalt blue, with a predominantly floral decoration. Each jar has three large cartouches separated by vertical bands with a ‘cash’ diaper pattern in white on a blue groun. Each panel is decorated with flowering trees and ornamental rocks, with flying birds and insects above. Around the shoulders and foot are three large ruyi-shaped lappets with a blue ground and meandering chrysanthemums and leaves in white; they are linked by smaller ruyi-heads. Around the neck and foot is a blue border, decorated with six interspersed white double circles with in the centre a white stylised flower. Between each circle are two demi-flowers, one facing down from the rim the other facing up from the shoulder. The high-domed lids have three lobed panels outlined with a thick blue line, decorated with rocks and flowering plants and crowned with blue lotus-bud finial. The undersides have a transparent glaze with a double blue ring. The matching beakers are similarly decorated in the same way on the outside, but the inside of the rim has a band of spikey foliage within a thin blue line.

Garnitures - or garnitures de chiminée - were a popular decorative element in 18th-century interiors, placed on cabinets, mantlepieces or cornices over doorways. They usually comprise of an uneven number of jars alternated with beakers (3,5 or 7) – but the most common number is 5. The porcelain would be ordered by the Dutch East India company (VOC) in many multiples and put together by dealers in Europe, once the shipment arrived from China. These blue and white wares were so popular, that the factories in Delft produced pieces with a very similar decoration, which may have in turn influenced what was ordered in China for the export market.

5

|

20

This garniture was in the former collection of Marc de Beauvais, 7th Prince de Beauvau Croan (1921–1982). Their former family seat in Lorraine, was magnificent Chateau de Haroué, now the Centre des Monuments Nationaux and a great monument itself. Marc and his second wife Laure, were great patrons of the arts, Laure also becoming the first president of Sotheby’s in Paris.

The Topkapi Saray Museum has two identical but mounted jars (TKS 15/4285 & 4519). A very similar garniture but with different lids, is depicted in Goidsenhoven.

The V&A London has a similar jar with different panel decoration (Acc.nr.C.807&A-1910). The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam and The Hodroff collection, Winterthur, both have several 5-piece garnitures.

21

22

23

China, Early 18th-century Ø: 26.4 cm

PROVENANCE

Eumorfopoulos Collection, 1927, no. E193 (ill.)

Sotheby & Co London, 1940, lot 345

With Sydney L Moss, London 1940

Private Collection, Paris Collection Baron & Baroness Vaxelaire, Belgium 2022

LITERATURE

Ayers 1972, nr.A466

Ayers 1999, p.75 nr.197

Ayers 2004, p.153 nr.178

Bartholomew 2006, p.42

Beurdeley & Raindre 1987, p.144-145 pl.209

Hobson 1925-1928, nr.E193 pl.53

London 1940, Lot 345

Paris 1960, nr.38 & illustrated

Welch 2008, p.94-95

Eumorfopoulos Water Dish

This thickly potted shallow water dish or tray, is enamelled all over on the biscuit in a rich turquoise enamel. It is modelled in the shape of a lotus leaf, the veins deeply incised. To one side is a black crab modelled in relief, the legs and claws slightly flatter. The elegant undulating edge of the leaf, curls up and has a line of black enamelling on the rim. On the underside of the leaf, the veins are moulded in relief, with a few minute firing spurs around the central circle. The minute crazing and small irregularities in the glaze, give the surface added depth and interest. When comparing the markings with other published examples, we discovered this dish was formerly in the collection of George Eumorfopoulos. It also carries a - as yet unidentified - collection label on the bottom with the letters CYM.

The crab with a lotus leaf is a regularly recurring theme in the Chinese arts. The crab (xie 蟹) is a rebus for harmony (xie 諧) and also the word for those who have passed the first examination towards official rank (xie). The lotus leaf (he 荷) is also associated with the word for harmony or peace (he 和). This allusion to harmony and success in exams, could be why this is a popular combination for scholars’ desk objects, such as this dish.

This dish was sold at the Eumorfopoulos sale at Sotheby’s in 1940 (lot 345), the results stating it was sold to dealer Sydney L. Moss Ltd. for £13 10s. The last owners were the Vaxelaire family, founders of Au Bon Marché department stores in Belgium and great patrons of the arts.

The Baur collection in Geneva has a strikingly similar dish, also with a crab and aubergine undulating rim. (nr.451). The Palace Collection, Beijing, has a similar turquoise lotus dish, but with a higher rim.

The Vergottis collection, Lausanne also has a turquoise dish with similar veining but with a chilong on the rim. The catalogue of Mme Wannieck auction in Paris, also shows a comparable dish with the same veining and black crab.

6 |

24

25

26

GEORGE EUMORFOPOULOS (1863-1939)

George Aristedes Eurmorfopoulos, was one of the most important and influential Chinese Art collectors in the first half of the 20th-century. He was born in Liverpool, of Greek parents who came from the island of Chios. He joined the Baltic Exchange in 1880 and joined the firm of Scaramanga, Manoussi & Co. in 1884, before moving to the maritime trading and financial firm of Ralli Brothers in 1902. He became a Vice-President of the firm in 1931, retiring in 1934.

Eumorfopoulos, popularly known as ‘Eumo’, started collecting in 1891. He eventually formed an astonishing collection of Chinese Antiquities, including Qing porcelain and Han, Tang and Song ceramics. Later he also added bronzes, jades, sculpture, painting, metal work, lacquer and glass. A member of the Karlbeck syndicate, he bought from all the major Chinese art dealers of the time. A third of his collection (over 1500 pieces) was bought from F.M. Frank & Co., 87 from John Sparks Ltd., 138 from Bluett and Sons. Others dealers included Yamanaka & Co. The renowned author R.L. Hobson, published a fabulous 6 volume folio catalogue on the ceramics collections (1925-28).

Importantly, he was the founding president of the Oriental Ceramic Society in 1921, remaining so until his death in 1939. He was also a member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club, the Royal Asiatic Society, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a benefactor of the Egypt Exploration Society. He actively promoted the interest in Chinese Ceramics, lending objects to the Exhibition of Chinese Applied Art at City of Manchester Art Gallery in 1913 and the international blockbuster Chinese Art exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1935, which he also helped organise. Eumorfopoulos lived at 7 Chelsea Embankment in London, to which he added a two-storey museum, to the back which he opened on Sundays.

Sadly, he was badly affected by the Depression in 1934, selling a large part of the first collection to the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum for the token sum of £100,000. The duplicates were sold in 1935, through the renowned London dealer Bluett’s. 800 pieces were also donated to the Benaki Museum in Athens, creating the first major of Chinese art collection in Greece. After this downturn, he proceeded to add to the residue collection again. This second collection was auctioned after his death at Sotheby’s in 1940. A final sale was held in 1944 after the death of his widow Julia Eumorfopoulos.

27

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

H: 8.7 cm | W: 7.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Collection Louis & Louise Cahen d’Anvers, France (label nr.63)

Collection Anthony & Yvonne de Rothschild - Cahen d’Anvers, (label nr.421), c.1930’s

Collection Renée Robesonde Rothschild 1940’s

LITERATURE

Bondy 1923, p.179

Boulay 2019, p.77

Emery 2020

Krahl 1996

Legé, 2022 (1)

Legé 2022 (2), fig.125

7 | Rothschild Lion Dogs

A pair of aubergine glazed enamel on biscuit lion-dogs - or ‘dogs of fo’ - standing on a turquoise leaf shaped base. They look left and right, mouths open, white unglazed teeth and tongue showing. The tails are curled over their backs, with moulded swirls dotted along the spine and around the necks. Against their back leg is a short tube for holding an incense stick. These type of figures were made for a scholar’s desk to perfume the room. But they were also very popular in 18th-century Europe, where they appealed as exotic curiosities.

The underside of both lions have an A. de Rothschild collection label (nr.421) – the letter A crossed over-written in pen with a Y. One lion has a second older label, with a printed monogram and a written number 63. This is the Cahen d’Anvers collection label, from whom Yvonne de Rothschild must have inherited Chinese porcelain.

Anthony de Rothschild (1887-1961), was an avid collector of Chinese ceramics, amassing a fabulous collection of early pottery and Ming fahua wares, as well as impressive Kangxi famille verte and enamel on biscuit pieces. Their collection was gifted, along with the family home Ascott House, to the National Trust in 1948 – where it can still be admired. However, some pieces from their personal collection were gifted to their daughter Renée (1927-2015). These were probably objects that her mother Yvonne inherited from her family in France, from either her mother Sonia or her famous socialite grandmother and patron of the arts Louise Cahen d’Anvers.

Similar aubergine glazed figures are in Burrell Collection, Glasgow (acc.nr.38.620 & 619) and Duberly Collection of Chinese Art, Winchester College (acc.nr.Ch70). A large group of these lions on leaf-shaped bases was recovered from the wreck of the Ca Mau, which sank in the South China Sea circa 1725.

28

29

ANTHONY DE ROTHSCHILD (1887-1961)

YVONNE DE ROTHSCHILD- CAHEN D’ANVERS (1899-1977)

Anthony Gustav de Rothschild (1887-1961), grew up in England and worked in the family banking business in London. A passionate collector like his father Leopold de Rothschild (1845-1917), he started collecting in earnest after serving in the First World War. His initial interest in Chinese ceramics, may well have been sparked by a trip with his brother to China in 1911. He also travelled extensively himself, keeping meticulous records of everything he bought on his journeys. His personal collection was augmented with mounted pieces he inherited from his parents. Some smaller famille verte and turquoise glazed objects were brought into the collection through his French wife Yvonne Cahen d’Anvers (1899-1977).

Yvonne Cahen d’Anvers was the daughter of Robert & Sonia Cahen d’Anvers – a distinguished Jewish financiers family in Paris. Her Grandmother Louise , who held a famous literary salon in Paris, was a great patron and collector of art - including Japanese lacquer and Chinese porcelain. Their art and antiques were displayed both at their house in Rue Bassano in Paris, as well as the family chateau Champs de Marne.

Anthony purchased his Chinese ceramics from the major oriental art dealers of the time, including, John Sparks, Gorer, Bluett & Sons and Frank Partridge in London; as well as C.T Loo in Paris.

He appears to have amassed most of his Chinese pieces during the 1920’s and 30’s, becoming an early lender and supporter to the Oriental Ceramics Society (est. 1921). He also lent 14 pieces to the famous Chinese Art Exhibition of 1935. His Chinese ceramics collection, included early pottery, coloured fahua wares from the Ming Dynasty (1386-1644), as well as famille verte and biscuit wares from the Kangxi period (1662-1722). Most pieces have an inscribed inventory label, correlating to acquisition notes, records and invoices kept for his purchases from 1910 onwards - these are now kept in the Rothschild family archives. The collection was mainly housed at his home Ascott House; presented in glass showcases, as well as dotted around the rooms amongst French and English 18th-century furniture.

The majority of the collection is still in Ascott House, which was endowed to the National Trust in 1948. The de Rothschilds also gifted pieces to major museums, as well as to various members of his family including their daughter Renée Robeson - de Rothschild (1927-2015). In 1996, in memory of his father, his son Evelyn de Rothschild oversaw the publication of the impressive collection catalogue, authored by Regina Krahl.

30

LOUISE CAHEN D’ANVERS – MORPURGO (1845-1926)

Louise Morpurgo was born in Triest, marrying the wealthy banker Louis Cahen d’Anvers (1837-1922) in 1886 and moving to Paris. They had five children, two boys Robert (1871-1933) & Charles (1879-1957) and three girls Irene (1872-1963) Alice (1876-1965) & Elisabeth (1874-1944).

Louise was a well-known Paris socialite, hosting a salon every Sunday in the Summer for writers, musicians, philosophers and artists. Louis and Louise were in fact the perfect representatives of a cosmopolitan spirit of the Belle Epoque, living in a Paris recently restyled by Haussmann. Through their ostentatious luxury lifestyle and internationalism, the family projected their increadible wealth and social success. They also avidly collected art and patronised artists, their young daughters famously portraited by Renoir.

Two great affectionados of oriental art Edmond Taigny and Louis Gonse, were close friends of Louise. A third collector Charles Ephrussi, editor of the Gazette des beaux-arts, was rumoured to be her lover. Through them she started collecting Asian artefacts in earnest, displaying her finds in her Paris house (2, rue de Bassano) and in the Chateau de Marne. She acquired Japanese enamels and lacquer wares, as well as Chinese porcelain from the Ming and Qing dynasties, frequenting auction houses and renowned antique dealers such as Desoye and Sichel.

The Cahen d ‘Anvers belonged to a group of very wealthy and interconnected Jewish banking families, including Camondo, Rothschild, Montefiore and Ephrussi. They intermarried and socialised together, many of them building grand houses around Parc Moncaeu. Louise’s daughter Irene married Moise Camondo – who left his house and collection to the French nation, the now famous Museum Nissim Camondo. These families and their art collecting, have recently come into the international spotlight again through the books by Edmund de Waal Hare with the Amber Eyes (2010) and Letters to Camondo (2021).

The house in Paris was left to their son Robert and the Chateau de Marne to the younger son Charles.Part of the collection was sold at auction in London in 1936 after her death.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Emery 2020

Krahl, 1996

Legé 2022

London 1936

31

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

H: 19 cm | W: 10.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Captain C.B. Kidd Collection, UK

Auction Dukes Dorchester, 2011, lot 1011

Anthony Du Boulay Collection, UK (label nr.PA171)

EXHIBITED

OCS exhibition 2016 London (label no.32)

LITERATURE

Little 2000, p.276-277

London 2016, p.67 nr.32

Dorchester 2019, p.77 Lot 115

Pei 2004, p.194-5

Welch 2008, p.203-204

An unusual enamel on biscuit figure of the Daoist goddess Xi Wangmu - Queen Mother of the West - seated crossed legged. Her black hair is styled in a high bun, held together at the back with a yellow pin; her unglazed face has a serene expression and she is smiling gently. Her hands come together under ample sleeves and she holds a green cloth with three peaches - glazed yellow and aubergine, with green leaves. She wears a green skirt and darker green cape over her shoulders, buttoned at the neck. Her main robes have been gilded over a red lacquer, which was possibly added later in Europe. The bottom is coarsely moulded and unglazed, with two labels – one for the Anthony du Boulay collection, the other for the Oriental Ceramics Society exhibition in 2016. There is a small hole in the back of the figure, which would be for letting the hot air out during firing. This charming figure, was probably made for display on a house altar of Daoist believers. Figures of Wangmu, appear to be much rarer than the more common smaller images of the Buddhist goddess Guanyin - as we know of no other comparable figure.

The Queen Mother of the West is often depicted with her magical peaches of immortality, which were said to grow in the gardens of her Jade Palace in the Kunlun Mountains. Her mythical peach trees only flowered once every 3,000 years, the fruit requiring another 3,000 year to ripen. On her birthday, this fairy queen would invite all the Daoist deities and immortals to the celebration - where they feasted on these longevity fruits. Xi Wangmu is one of the most iconic and popular Daoist female deities in Chinese folklore, worshipped for her magical powers and association with longevity.

Anthony du Boulay (1929-2022), was a world-renowned Chinese porcelain specialist, with a fantastic eye. He worked at auction house Christies from 1949-1980, where he was key in furthering the scholarship in the field of Chinese ceramics. He was a greatly respected authority, writing numerous key publications on the topic, which are still considered important research references today.

8 | Xi Wangmu

32

33

34

35

Japan, Arita Edo Period (1603-1868), 1680-1700

H. jars: 69 cm | H. vases: 58.9 & 59.9 cm

PROVENANCE

De Bruin van Baal Collection, The Netherlands 1985 (Label nr.50-J)

R. Verhoeven Collection, The Netherlands 2020

LITERATURE

Arts 1983, p.132

Ayers, Impey & Mallet 1990, p.91-92

Ferguson 2016, p.7-19

Hartog 1990, p.130 nr.158

Impey 2002, p.95 & p.98 nr.103

Jörg 2003, p.259-261 & nr.333

Koeppe 1992, ill. p.360, P.386-7 nr.K57 a-e

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1972, p.34-37 p.99

fig.146

Ströber 2001, p.156 nr.69

9 | Large Arita Garniture

A magnificent underglaze blue and white garniture with an octagonal section, comprising two beaker and three covered jars. The three large ovoid jars, have a high neck rising from sloping shoulders and stand on a sturdy round stepped foot. The matching octagonal domed covers, have a flat rim and dark blue drop-shaped pointed finials. The two beakers have everted round mouths and stand on a distinctive bulging foot which turns sharply inwards – which is referred to as a takefushi foot. Both beaker vases, jars and covers are decorated in a good dark cobalt blue. The main bodies have a continuous scene, with large elegant long-tailed ho-ho birds amongst rocks, flowering branches and leafy willow trees. The neck of the jars have a band of karakusa scrolls and the shoulders have dense scrolling foliage with chrysanthemum heads, under a band of narrow lappets. Around the foot-rim is a border of pointed half-leaves. The unglazed porcelain clay on the inner rim of the covers, have some irregular orange colouration. Often seen on Japanese porcelain, this comes from iron particles in the clay which have seeped into to the unglazed areas during firing. Numbered labels for De Bruin van Baal collection are on numerous pieces of the garniture.

These type of vases were produced, in the what is referred to as the middle period of the Japanese export porcelain. Elements of Chinese Kraak and Transitional wares have been absorbed into the Japanese motifs, forming its own unique recognisable style. The octagonal shape, is typically Japanese and the decoration with landscapes, were predominantly produced in the late 17th and early 18th-century.

Porcelain was first made in Japan in the early years of the 17th-century, at kilns in and around the town of Arita on the the island of Kyushu. The very earliest pieces produced, were primarily designed for the domestic market as tea wares. Production increased significantly from 1650 onwards, with a large part of the industry being directed towards the making of ceramics for export to Europe.

36

37

The term ‘Arita’ was traditionally used when referring to export wares in blue and white porcelain, mostly emulating Chinese styles. Large jars like these, were known in Japan as Chinkō Tsubo (aloe jar), presumably because the aromatic wood was transported in these jars by the Dutch East India traders.

Garnitures are a European invention, most commonly comprising sets of three covered jars and two beaker vases, with a matching decoration. They were initially produced as single pieces presented in massed arrangements and later grouped as matching sets. Garnitures were greatly favoured in Europe and were extremely expensive to acquire. They could only be afforded by the wealthiest noble families, who would display them as a reflection of their power and affluence in their palaces and houses.

Mr. Popke de Bruin (1893 – 1975) & Mrs. Hendrika Petronella van Baal (1890 - 1985) – had a large collection of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, accumulated during their lifetime. The collection passed on by to their daughter Cornelia de Bruin (1916-2008), who continued to collect. It then passed by descent to the previous owner.

The Lemmers- Danforth collection in Wetzlar, has an almost identical garniture (K57 a-e). Comparable vases and beakers of the same shape and decoration, are in the former collection of Augustus the Strong in Dresden (PO1452, PO4750 & 51 PO4746 & 49). Kasteel Twickel, Delden, The Netherlands, has three comparable covered jars, but no beakers (nr.JK4). The V&A, London have a single comparable jar (acc.nr.FE.6-1977), without a lid.

38

39

China, Kangxi period (1662-1722)

Ø: 24.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Possibly Potken Family, Ceylon, c. 1720

Private Collection, The Netherlands, 2019

LITERATURE

Castro 2007, p.105

Kroes 2007, p.111-112 nr.10-11, p.541 nr.10-11

MacGuire 2023, p.73 nr.35

Suchomel 2015, p.237 nr.116

10 | Potken Plates

A pair of Chine-de-Commande underglaze blue plates with broad flat rims, decorated with an armorial shield. The broad rim of the plates has a band of radiating flower stems including daisies, narcissus, anemones and irises. The centre of the plates have a ring with a denser flower and foliage pattern. In the centre is circular medallion, with the outline of a shield and a cooking pot (or cauldron) in the middle. The underside has a lozenge (hua) within a double blue circle, with two flower sprays on the rim. The shape and decoration of these plates, clearly indicate it was intended for the export market. Amusingly, the pot is incorrectly represented by the Chinese potters, as it is depicted upside down within the shield.

The armorial device on these plates, is popularly referred to as those of ‘Potken’. This shield is probably using the pot as ‘punning arms’ (sprekend wapen), the cauldron being a fun reference to the name of the family. It is thought that these plates were possibly made for the Dutch Potken family from Oldenzaal (Overijssel) – who had strong VOC connections. Gerardus Potken (1695-1762) spent his adult life as a vicar in Colombo, the capital of Ceylon; which meant he would have had good contacts for ordering personalised Chinese porcelain. The other suggested possibility is that it is for the Portuguese family of Caldería – also a pun on their name.

The armorial device, shape and decoration of this plate all point to it being made to order by the Dutch East India traders. The flat shape and broad rim of this plate, suggest that a Dutch pewter plate may well have served as an example. The decoration on the rim also clearly shows Western influence in the slightly stiff repetition of different flowers, probably based on comparable European printed designs.

The Frelinghuysen Collection, USA, has three plates with the same decoration. Plates with a similar floral décor, but without the armorial shield, are in the Groninger Museum (inv.nr.2001.0105), Kasteel Sypensteyn (inv.nr.8360) and Schwarzenberg Family Collection, Prague (inv.nr.CDU 131).

40

41

China, Kangxi period (1662-1722), c.1700

Colour enamels late 18th-century. Later silver lid

H: 20.3 cm

PROVENANCE

Lancastre Family , Portugal, c.1700

Private Collection, Spain 2021

LITERATURE

Castro 1988, p.51

Castro 2007, p.112

Espir 1997, p.109-126

Espir 2005, p.239 fig.43

Lisbon 1999, p.210-211

MacGuire 2023, p.66 nr.27

Pinto de Matos 2011, p.353-255

Sargent 2012, p.499-500

Varela Santos 2007, p.796-7

Lancastre Vase

An unusual small armorial vase, made for the Portuguese market. The globular body, has lotus leaves moulded in relief around the base. It has a high neck and stands on a domed foot. It is decorated in underglaze blue with vines and grapes, with a shield under a large eagle bearing the incomplete arms of the Portuguese Lancastre family. The neck and foot are decorated with squirrels, as well as grapes and vine leaves. The vase has additional striking over-glaze colours in red, green and gold, which would have been added after its arrival in Europe - probably in England. On the centre of the base is a small artemisia leaf mark and the initials R H are incised into the side of the foot. It has a later silver lid.

.

The influential and wealthy Lancastre family, are now particularly famous for creating a ceiling covered with Chinese porcelain at Santos Palace in Lisbon (now the French Embassy). This vase was perhaps ordered by Luis de Lancastre (1644-1704) - 4th Count of Vila Nova di Portimào. The other possibility is that it was ordered, slightly later as part of a larger service for the wedding of Pedro De Lancastre (1697-1752) - 5th Count of Vila Nova di Portimào in 1711. It is recorded that, the first ordered pieces were said to have been rejected due to the errors in the coat of arms.

This type of over-decorating of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, was practised in Holland, England and Germany from the early 18th-century. It is referred to as Amsterdams Bont in Holland, clobbering in England and hausmaler in Germany. Plainer pieces would be enhanced with polychrome enamels, gilding, or even entire designs, to the Western taste. The porcelain was then refired at a lower temperature (petit feu) in muffle kilns, to fix the colours to the body.

Lancastre vases of a similar form, with just underglaze blue and white decoration, can be found in various collections. The Frelinghuysen collection has two, both with a porcelain lid. The Collection M.H. Castro, Portugal, has one with a later silver lid and the M.O.P. Collection, Lisbon has one with a porcelain lid.

11 |

42

43

China, Warring States Period (475-221 BC)

H: 50 cm | W: 4.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Purchased in Hong Kong 1994

With Vanderven & Vanderven 1996

F. Wirtz Collection, Germany 2022

LITERATURE

Bennett 2018, p.66-67

Washington 1982, p.77 nr.30

Macau 2007, nr.76 & 79

Seattle 2001, p.246 nr.90

12 | Bronze Jian

A bronze double-edged sword, with a flattened lozenge-shape crosssection. The blade, which tapers to a sharp tip, is embellished with a geometrical pattern in gold. The hollow trumpet form handle, ending in a disk shape pommel, sits on a slim diamond shape hilt-guard. The sumptuous gold decoration, indicates it would have been made for someone of high rank and was probably a ceremonial or presentation sword. The handle may well have originally been covered with ornamental braided silk, to cushion the hand and improve grip.

Swords were the first weapons cast from bronze in China, the earliest dating from the Zhou period (1100-256 BC). Initially swords, which evolved from daggers, tended to be short (about 35 cm), gradually becoming longer and more embellished. During the Warring States period (475-221 BC) swords are generally of a type known as a Jian – characterized by its straight double-edged blade. By this period, the sword had developed into a formidable weapon with strong but flexible blades, which could be up to 50 cm in length.

The National Palace Museum, Taiwan has a very similar sword. Two similar shaped swords, but without gold, are in the Sanmenxia Museum, Henan. A sword inlaid with a silver inscription of the King of Yue, is now in the Henan Museum, China. The National Museum of Asian Art, Washington also has a similar shaped sword from the same period (acc.nr.F1979.6).

44

45

46

47

China, Sichuan, Eastern Han Dynasty

(25 – 220 AD)

H: 49.3 cm

PROVENANCE

With Galerie J. Barrère, Paris 1998

J.J. Studzinsky CBE Collection, UK

2019

LITERATURE

Caroselli 1987, p.74 & p.117 nr.38

Elias 2023, p.97-108

Jacobson 2013, p.100-103

Lim 1987

Liu 1991, p.119

Rawson 1996, p.207-209 nr.109 & 110

Seattle 2001, p.298 nr.111

Zurich 1996, p.422-426 nr.110-111

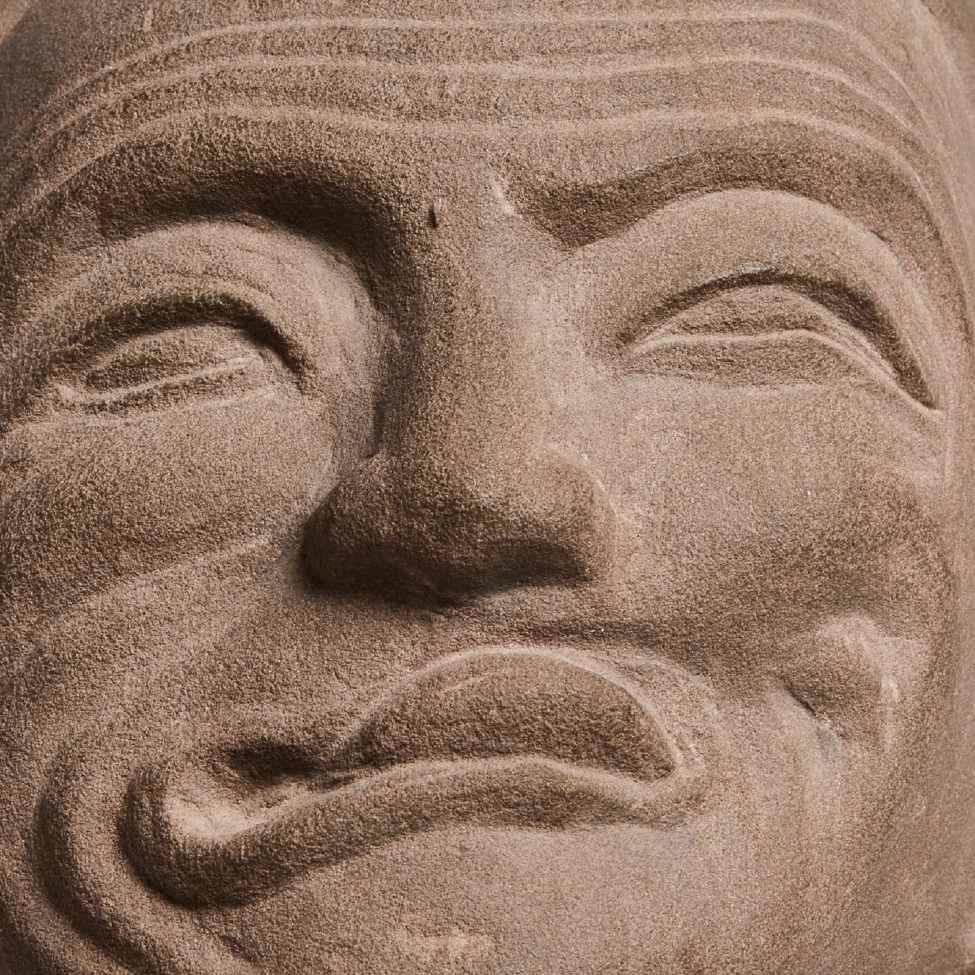

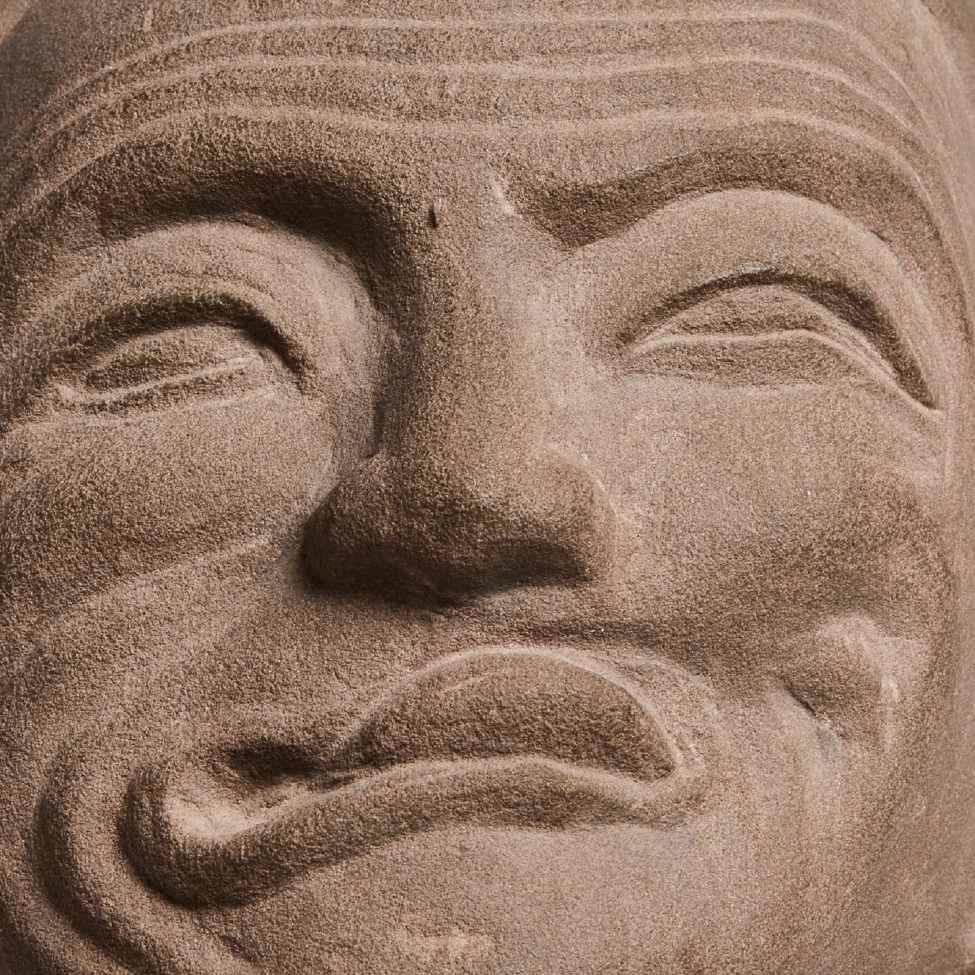

13 | Stone Drummer

This very rare carved stone figure of an entertainer, is captured whilst performing. He has a very exagerated facial expression, head thrown back, forehead wrinkeled, eyes squinting and his togue sticking out. He has a slightly squat body, with his back arched showing an ample belly. He stands upright with knees bent; in his left hand he holds a small round drum and in his right he holds a beating stick. His upper-body is unclothed except an armband on his left arm. He wears low-slung voluminous trousers, with a sagging waistband, just about covering his bottom half. On his head he wears a close fitting cap tied over a pointy bun. The comical and caricatural posture and facial expression, show the sculptor’s desire to immortalise the performance mid-act. Drummers such as this specialized in a kind of part-spoken, part-sung storytelling called shouchang.

This figure is stylistically related to a known group of pottery figures of entertainers, which have been excavated from highranking Han dynasty tombs. These exceptional figures with their lively expressiveness, appear to be unmatched in the art of the ancient world. Their popularity, must mean such entertainers were highly appreciated for their virtuosity and an important part of court life. Other known figures from this group - either drumming, singing, acting or miming - have been found over a large geographical area covering Chengdu Plain in Sichuan Province. Chengdu city itself was a wealthy trading hub during the Han Dynasty, attracting commerce and travellers from far beyond the region. This economic growth and increased wealth would have also triggered a flowering of the arts and literature.

48

49

50

The comical appearance, silly expressions and exaggerated gestures of these figures are part of the Shoucheng storytelling performanceperhaps comparable to that of a court jester. The body shape may indicate these figures were perhaps dwarfs, who are generally known to have been popular as Chinese court performers. It is known that native as well as foreign dwarfs trained as acrobats, jugglers, tightrope walkers, dancers and musicians. These exotic entertainers formed troupes, which circulated in China from region to region, entertaining all levels of society. Similar entertainers also appear on tomb tiles, depicting scenes of juggling and sword balancing.

We have not been able to find a similar figure carved from stone. However, comparable ceramic figures of drummers can be found in private as well as in museum collections. The Sichuan Provincial Museum has a similar postured drummer made of pottery. The Minneapolis Institute of Art, has a pottery figure of a squatting drummer (acc. nr.2003.101). A brickwork tile exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum, New York from the same period, has a relief with a banquet scene with entertainers.

51

China, Tang Dynasty (618-907),

Late 7th century- early 8th century

H: 73.2 cm | W: 38 cm | D: 33.5 cm

PROVENANCE

With Galerie J. Barrère, Paris 2005 (dated expertise)

P. De Poortere Collection, Belgium 2023

LITERATURE

Falco Howard 2006, p.298-329

New York 2007, p.92-93 nr.39

New York 2008, p.60-63 nr.8

Lefebvre d’Argencé 1974, p.186-7 nr.88

Rastelli 2008, p.142 & 276 nr.35

Taipei 1997, p.167 p.256 nr.64

Seated Buddha

A grey limestone figure of Buddha, seated on a stone pedestal. Both legs are pendant, in a position known as the pralambapadasana – the so-called ‘European’ position; his left hand rests on his knee, palm facing down. Buddhas seated in this pose can be identified as Maitreya - the Buddha of the future. The body is clad in a diaphanous monk’s robe (sanghati) with cascading crisp folds, covering both shoulders but partially exposing the chest. Concentric sharp pleats fall over his lap, the shape of the legs and knees clearly visible beneath the cloth. The neck has several folds of skin, which is similar to that of other sculptures from this period. He sits on a square plinth, with the robes hanging over the edge. The head, right hand and lower legs are now missing.

During the Northern Qi and Tang dynasties there was much religious conflict between Buddhism -which had gradually entered China from India - and the existing ancient Confucian and Daoist beliefs. This lead to several waves of dismantling and destruction of religious monasteries, temples and complexes. Buddhist sculptures would be removed or sometimes damaged and buried in pits nearby. This explains why this type of early religious sculpture is not always complete.

A stylistically very similar seated Buddha, also seated on a square plinth and dated 686, from the Liang-sheng T’ang collection was exhibited in the National Palace Museum in 1997. Another complete with its full pedestal and head, is in the Avery Brundage Collection, San Francisco (B60 S115+). Related figures from the same period, but in a lotus posture, are in the Art Institute, Chicago (acc.nr.1930.83) and the Beilin Museum, Xian.

14 |

52

53

54

Buddhas seated in the pralamba-padasana position can be identified as Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future

55

China,. Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

H: 36.4 cm | W: 18.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Madame L. Wannieck Collection, France 1960 (Label & nr.68)

Private Collection, Switzerland 2020

PUBLISHED

Wannieck Sale Catalogue, Paris 1960 (pl.1 nr.68)

LITERATURE

Ayers 2016, p.621 nr.1446 & p.624 nr.1450-51

Pinto de Matos 2003, p.150, nr.39

Paris 1960, pl.1 nr.68 (label)

Krahl 1996, p.422, nr.240

15

| Wannieck Buddhist Lions

A pair of large biscuit Buddhist lion figurines (Shi), each standing on rectangular aubergine plinths with ruyi-head piercings either side. The lions are freely glazed on the biscuit, in purple and turquoise. The lioness looks to the right, a lion cub jumping up her right leg; the male looks to the left, his paw resting on a pole with a revolving openwork ball. Both have open mouths, the white unglazed teeth bared and tongues sticking out. The black eyeballs protrude and are articulated. Stylized curls in purple enamels decorate the top of their heads, chins, necks and run down their backs. A partially removed yellow label reads Collection Wannieck, Paris and a small label with the number 68, corresponds to the number in her 1960 sale catalogue. They also have other larger, as yet unidentified, labels with a green border.

These figures formed part of the private collection of Paris dealer and connoisseur Mme Wannieck. Maison L. Wannieck was an renowned Asian art dealership in Paris, established in 1909. Leon and MarieMadeleine Wannieck, who had excellent contacts in Beijing, were able to buy directly from China in the early 20th century. Despite the great political upheavals of the time, they also travelled there on numerous occasions, buying artefacts to sell to collectors and museums in France and further afield. Unusually for this period, they dealt with early ceramics, as well as Ming and Qing porcelains. They also built a formidable private collection of Chinese porcelains and a comprehensive study library, which were both sold upon the death of Mme Wannieck in 1960.

56

57

58

Lions ( 獅 shi) - often referred to in the West as Fo Dogs - are very popular motifs in Chinese art, even though they are not indigenous to the country. They actually bear little resemblance to real lions (or dogs!) and are usually stylized fantastical creatures with exaggerated features. Traditionally, these creatures are considered to be the protectors of Buddhist wisdom and often found as guardian statues in front of buildings and temples. Usually they are portrayed seated in pairs - a male and female. They can be easily identified, as the female is always portrayed protecting her cub and the male standing on a ball.

Similar coloured lion-dogs, already appeared to be popular in 18th-century Paris. Two pairs are recorded in the sales of the time: one in the Julienne sale in 1767 and another pair in the 1768 Gaignat sale in Paris. A similar pair formed part of the Anthony de Rothschild Collection., UK (inv.nr.324). The Porzellansammlung, Dresden, also has two pairs (PO8952-3 & PO8950 & 54). An elaborate clock in the Royal Collection, UK, has a pair of comparable lions mounted into the ensemble (RCN2867); as well as a smaller comparable pair which served as a taper holder (RCN3573.1-2).

59

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

Ø: 28 cm

PROVENANCE

With Kunsthandel Bernheimer, Munich, 1980’s (label)

Private Collection, Germany 2023

LITERATURE

Bartholomew 2006, p.117

Welch 2008, p.156

16 | Basin with Shizi

A highly unusual basin, finely enamelled in the famille verte colour palette, with gold highlights. The deep basin, has gently rounded sides rising to an everted rim. The interior is delicately enamelled with a large scene of a bushy-maned Buddhist lion-dog (shi zi 獅 ), with two cubs clambering on her. The lioness has a green body with a red mane, striped chest and a striking scarlet nose. She looks joyfully at a brocade ball in front of her, which is attached to green flowing ribbons. Curiously, out of her mouth comes a speech ribbon, with at the wide end has a tiny gold lion playing with three balls - perhaps she is telling her cubs to come and play. The wary looking cubs are yellow with a blue mane. The cavetto of the basin is left undercoated; but the rim has a border with a brightly coloured continuous scroll of dense flowers and foliage on a frogspawn ground. The underside is undecorated and carries a Bernheimer München label.

Portrayals of Buddhist lions were popular in China, due to its auspicious connotations. The depiction of a large lion and young cubs playing with brocade balls, forms the pun taishi shaoshi, which translates as ‘May you and your descendant achieve high rank’. The flying ribbons tied to the ball are an added symbol for longevity. Additionally these terms ‘senior lion’ and ‘little lion’, are titles for high-ranking court positions in Imperial China – both highly prestigious. One is that of Grand Perceptor or the Emperor’s Teacher (taishi) and the other of Junior Guardian or Crown Prince’s Mentor (shaoshi).

Kunsthandel Bernheimer in Munich, was a founded in 1864 by Lehmann Bernheimer. Starting out as a textile shop, they quickly developed into specialists dealers of high quality objects d’art. They moved into their new multi-storey state-of-the-art ‘art palace’ in 1889, becoming an internationally celebrated address. Clients included the Bavarian royal family, collectors and museums. During the war years the business was confiscated, but luckily returned to the Kunsthaus again after the war. In 1987 the astonishing Bernheimer building was finally sold to pay death duties. The business’ final Munich location, then specialised in Old Master paintings, closed indefinitely in 2016 and was absorbed into Colnaghi of London.

60

61

62

63

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

Ø: 16.6 cm

PROVENANCE

With Morpurgo, Amsterdam 2019 (label nr.492)

LITERATURE

Welch 2008, p.24&34

Poem Plates

A pair of famille verte plates, with flowers and a two line verse on a white ground. They are each decorated on the right-hand side with flowers and a rock; one with peonies and pomegranate, the other with chrysanthemums. Both have poetic inscriptions in black signed with a seal and a mug wort leaf in iron-red. The reverse is simply decorated under the rim with two red flower sprays. On the back are handwritten Morgpurgo inventory labels, with stock numbers and price code. Also two larger labels with the translation of the poems in Dutch, written with a typewriter. The two-line inscriptions read vertically from right to left.

The plate with chrysanthemums is inscribed with: The whole garden looks bleak (in late frosty autumn), While the last few chrysanthemums give off a refreshing fragrance Bamboo Stone (name seal)

These lines appear to be from a four-line poem about the resilience of chrysanthemums blooming in late autumn from Stories to Awaken the World by Ming Dynasty poet Feng Menglong. The Chrysanthemum is the Chinese flower associated with autumn and the ninth lunar month, so the verse is an fitting accompaniment to the decoration.

The plate with peonies and pomegranate reads: It’s (again) the blossom season beyond the exquisite terrace railing, Where the new appearance cannot conceal the glorious past Bamboo Stone (name seal)

The peony is the Chinese flower of spring and the third lunar month, so this plate may be associated with spring. Perhaps these plates belonged to a whole series corresponding to the months of the year, each with its own flower and appropriate verse.

17 |

64

65

66

Fine bodied and colourful famille verte wares were fired twice. After shaping, they were glazed and high-fired. Then they would be decorated with bright enamels and re-fired at a lower temperature of 800ºc in a so-called muffle kiln. In addition to the various vivid greens, the colour-set includes yellow, aubergine and a coral toned iron-red, black and blue. Gold is also applied, to further enhance the decoration.

Kunsthandel Jozef M. Morpurgo, was founded in Amsterdam in 1869 and run consecutively by four generations of the family until closing in 2018. They dealt in high quality antiques, glass and Oriental porcelains, and were one of the leading dealers in The Netherland. Morpurgo was amongst the founders of one Europe’s earliest antiques fair in Delft in 1949, intended to renew the interest in antiques after the war.

There is a series of similar plates in the Porzellansammlung, Dresden, also including other plants such as bamboo and plum blossom (PO6515 & PO6517). The British Museum London has a pair of small plates with landscapes and poems (1947,0712.301.a-b), signed in a similar way in iron-red.

67

China, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

H: 19.6 cm

PROVENANCE

With Duveen Liverpool (gold lacquer seal)

Private Collection, London 2023

LITERATURE

Duveen 1935

Davids & Jellinek 2011, p.159

Secreest 2004, p.71-2

A ginger jar and cover, decorated in the Chinese Imari style with the distinctive underglaze cobalt blue and iron-red colours. It has a rounded ovoid shape, the body decorated with scrolling lotus leaves and flowers. On the high shoulders, under the high unglazed mouth-rim, is a band with a geometric sunburst pattern in triangles. The flat lid is decorated with a single blue flower and iron-red foliate scrolls; a border of hanging petals, alternating in red and blue, runs around the side of the lid. The underside of the jar is undecorated and has an oval gold lacquer seal, stamped with the name J.M. Duveen & Son – Liverpool.

Vessels of this shape are reffered to as ‘ginger jars’ in the West, allegedly because they were often imported containing ginger. On arrival in Europe, they would have probably only had a function as a luxury decorative object. In China however, these type of jars were considered practical and used to hold a variety of substances or were simply ornamental objects.

James Henry Duveen (b.1873), also known as Jack, was a nephew of Joseph Duveen Sr. and a cousin of the famous dealer Joseph Duveen (Lord Duveen of Millbank). He ran the family’s Liverpool gallery J.M. Duveen & Son (named for his step-father) at 47 Bold Street, selling Chinese porcelain to Lord Lever in the early 20th-century. He later moved the business down to London, firstly to 38 Dover Street in 1906 and then defiantly to 9 Old Bond Street in 1908 – a few doors down from the Duveen Brothers shop. This proximity to his cousin’s premises, did not go down well with the rest of the family. Jack in turn initiated a lawsuit for slander against his famous cousin Joseph in 1910, accusing him of compromising a number of sales to wealthy clients including Sir William Bennett and William Lever. In 1935 James Henry published a book Collections and Recollections. A century and a half of art deals – giving his perspective of the family history and antiques business.

A similar shaped jar, but decorated with a phoenix and qilin, is in the Groninger Museum (acc.nr.1929.0512). Keramiekmuseum Princessehof has one of a similar shape, but decorated in underglaze blue with a landscape (nr.NO05183).

18 | Duveen Jar

68

69

Chinese captions

1 | Preening Goose

白鵝回首(我如意)

中國清代乾隆年間

高:26.3公分; 寬:24.6公分

2 | Dresden Bottle

德累斯頓瓶

中國清代康熙年間

高:21.9公分

6 | Eumorfopoulos Water Dish

尤氏舊藏蓮葉筆洗

中國清代(18世紀早期) 直徑:26.4公分

3 | Dresden Plates

德累斯頓盤

中國清代康熙年間

直徑:27.5公分

4 | Royal Figures

宮廷人像

人像:中國清代(約18世紀)

鍍金底座:約18-19世紀

高:18公分;寬:13.1公分

5 | Export Garniture

出口瓷瓶罐套件

中國清代康熙年間

高:43公分

7 | Rothschild Lion Dogs

羅斯柴爾德舊藏獅子狗

中國清代康熙年間

高:8.7公分;寬:7.8公分

8 | Xi Wangmu

西王母像

中國清代康熙年間

高:19公分;寬:10.6公分

9 | Large Arita Garniture

有田燒瓶罐套件

日本(約公元1700年)

高:69公分

10 | Potken Plates

波特金舊藏瓷盤

中國清代康熙年間

直徑:24.5公分

70

11 | Lancastre Vase

蘭卡斯特將軍罐

中國清代康熙年間(1662-1722)

高:20.3公分

12 | Bronze Jian

青銅劍

中國戰國時期

長:50.5公分;寬:4.8公分

13 | Stone Drummer

鼓樂俑

中國漢代

高:49.3公分

14 | Seated Buddha

坐佛

中國唐代

高:73.2公分;寬:38公分;

深:33.5公分

15 | Wannieck Buddhist Lions

萬聶科舊藏福犬

中國清代康熙年間

高:36.4公分;寬:18.5公分

16 | Basin with Shizi

福犬瓷盆

中國清代康熙年間 直徑:28公分

17 | Poem Plates

花鳥題詩盤

中國清代康熙年間 直徑:16.6公分

18 | Duveen Jar

杜維因舊藏罐

中國(約18世紀) 高:19.6公分

71

Bibliography

Arts 1983

P.L.W. Arts, Japanese Porcelain – A Collector’s Guide to General Aspects and Decorative Motifs, Lochem, 1983

Ayers 1972

John Ayers, The Baur Collection, Chinese Ceramics, Vol. III, Genève, 1972

Ayers, Impey & Mallet 1990

John Ayers, Oliver Impey & J.V.G. Mallet, Porcelain for Palaces – The Fashion for Japanese Porcelain in Europe 1650-1750, Exhibition catalogue of The Oriental Ceramics Society with The British Museum, London, 1990

Ayers 1999

John Ayers, Chinese ceramics in the Baur Collection, Vol. I & II, Geneva, 1999

Ayers 2004

John Ayers, The Chinese Porcelain Collection of Marie Vergottis, Lausanne, 2004

Ayers 2016

John Ayers, Chinese and Japanese Art in the Royal Collection of her Majesty the Queen, Vol. I-III, London, 2016

Bartholomew 2006

Terese T. Bartholomew, Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art, San Francisco, 2006

Bennett 2018

Natasha Bennett, Chinese Arms and Armour, Leeds, 2018

Bertoldi 2006

Cristiana Bertoldi, La collezione di porcellane orinettale Ala Ponzone, Collection Catalogue Museo Civico di Cremona, Cremona, 2006

Beurdeley & Raindre 1987

Michael Beurdeley & Guy Raindre, Qing Porcelain; Famille Verte, Famille Rose, New York, 1987

Bondy 1923

Walter Bondy, Kang-Hsi, Eine Blüte-Epoch Der Chinesischen Porzellankunst, Munich, 1923

Castro 1988

Nuno de Castro, Chinese Porcelain and the Heraldry of the Empire, Oporto, 1988

Castro 2007

Nuno de Castro, Chinese Porcelain at the Time of the Empire: Portugal | Brazil, Lisbon, 2007

Caroselli 1987

Desroches 1976

Jean-Paul Desroches & Alain Jacob, Chine: Poteries grés biscuits, Paris, 1976

Dorchester 2019

The Anthony du Boulay Collection –Connoisseur, Gentleman, Collector, Auction Catalogue Duke’s, Dorchester / London, November 2019

Susan Caroselli, The Quest for Eternity: Chinese Ceramic Sculptures From the People’s Republic of China, London, 1987

Cohen & Motley 2008

Michael Cohen & William Motley, Mandarin and Menagerie: Chinese and Japanese Export Ceramic Figures, London, 2008

Davids & Jellinek 2011

Roy Davids & Dominic Jellinek, Provenance: Collectors, Dealers & Scholars: Chinese Ceramics in Britain & America, England, 2011

Duveen 1935

James Henry Duveen, Collections & Recollections: A Century and a Half of Art Deals, London, 1935

Elias 2023

Hajni Elias, Laughter and Lamentation: Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD) “Spirit” Entertainers from Sichuan, China, Arts of Asia Spring, 2023, p.97-108

Emery 2020

Elizabeth Emery, Reframing Japonisme – Women and the Asian Art Market in Nineteenth Century France 1853-1814, London, 2020

Espir 1997

Helen Espir, Pretty China: Oriental Porcelain Decorated in Europe in the 18thCentury, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramics Society - Vol. 62, London, 1997/1998, p.109-126

Espir 2005

Helen Espir, European Decoration on Oriental Porcelain 1700-1830, London, 2005

Ferguson 2016

Patricia Ferguson, Garnitures, London, 2016

72

Fuchs & Howard 2005

Ronald W. Fuchs II & David S. Howard, Made in China; Export Porcelain form the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection at Winterthur, Seattle, 2005

Goidsenhoven 1936

Jörg & van Campen 1997

Christiaan J.A. Jörg & Jan van Campen, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Amsterdam / London, 1997

Kroes 2007

Jochem Kroes, Chinese Armorial Porcelain for the Dutch Market, Zwolle/The Hague, 2007

Legé 2022 (1)

J.P. van Goidsenhoven, La Céramique Chinoise sous les Ts’ing 1644-1851, Brussels, 1936

Hartog 1990

Stephen Hartog, Pronken met Oosters Porselein, Zwolle, 1990

Hobson 1925-1928

R.L. Hobson, The Eumorfopoulos Collection; Catalogue of the Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery & Porcelain, London, 1925 -1928

Howard & Ayers 1978

David S. Howard & John Ayers, China for the West; Chinese Porcelain and other Decorative Arts for Export illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection, Vol. I, London / New York, 1978

Impey 2002

Jörg 2003

Christiaan J.A. Jörg, Fine & Curious, Amsterdam, 2003

Oliver Impey, Japanese Export Porcelain –Catalogue of the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Amsterdam, 2002

Jacobson 2013

Robert Jacobson, Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, 2013

Jörg 2011

Christiaan J.A. Jörg, Famille Verte. Chinese Porcelain in Green Enamels, Exhibition Catalogue Groninger Museum, Groningen, 2011

Kassel 1990

Porzellan aus China und Japan; Die Porzellangalerie der Landgrafen von HessenKassel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Kassel, Berlin, 1990

Koeppe 1992

Wolfram Koeppe, Die Lemmers- DanforthSammlung Wetzlar. Europäische Wohnkultur aus Renaissance und Barock, Heidelberg,

1992

Krahl & Ayers 1986

Regina Krahl & John Ayers, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul; A complete catalogue, part III: Qing Dynasty Porcelains, London, 1986

Krahl 1996

Regina Krahl, The Anthony de Rothschild Collection of Chinese Ceramics, The Eranda Foundation, Oxford, 1996

Alice S. Legé, From Trieste to Paris, Louise de Morpurgo and the Cahen d’Anvers Family, Connoisseurs, Collectors and Dealers of Asian Art in France, 1700-1939, AGORHA online source, 2022

Legé 2022 (2)

Alice S. Legé, Les Cahen d’Anvers en France et en Italie: Demeures et choix culturels d’une lignée d’entrepreneurs, Institut Francophone pour la Justice et la Démocratie, Tome 223, France, 2022

Lefebvre d’Argencé 1974

René-Yvon Lefebvre d’Argencé, Chinese, Korean and Japanese Sculpture, The Avery Brundage Collection Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, New York, 1974

Lim 1987

Lucy Lim (ed.), Stories from China’s Past: Han Dynasty, Pictorial Tomb Reliefs and Archaeological Objects, San Francisco, 1987

Lisbon 1999

Jorge Alves, Maria Antonia Pinto de Matos, Mary Lobo Antunes & Rui

Loureiro, The Porcelain Route: Ming & Qing Dynasties, Exhibition Catalogue Fundçào Oriente, Lisbon, 1999

73

Bibliography

Little 2000

Stephen Little, Taoism and the Arts of China, Exhibition Catalogue The Arts Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 2000

Liu 1991

Liu Liang-Yu, A Survey of Chinese Ceramic: Early Wares: Pre-Historic to Tenth Century, Taipei, 1991

London 1936

Chinese and continental porcelain and objects of art from the collection of the late Comtesse Cahen d’Anvers, Auction Catalogue

Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 11 June 1936

London 1940

The Eumorfopoulos Collections: Catalogue of the Celebrated Collection of Chinese Ceramics, Bronzes, Gold ornaments, Lacquer, Jade, Glass and works of Art formed by the late George Eumorfopoulos, Esq (sold by the order of Mrs. Eumorfopoulos and of the Executors), Exhibition Catalogue Sotheby & Co, London, 1940

London 2016

China Without Dragons Rare Pieces from Oriental Ceramic Society Members, Exhibition Catalogue Oriental Ceramics Society, London, 2016

London 1954

Queen Mary’s Art Treasures, Exhibition Catalogue Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1954

London 1964

The Ionides Collections Catalogue: Important Chinese Porcelain and Works of Art, part II, Auction Catalogue, Sotheby’s & Co, London 18 February 1964, Lot 273

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1972

D.F. Lunsingh Scheurleer, Japans porselein met blauwe decoraties uit de tweede helft van de zeventiende eeuw en de eerste helft van de achttiende eeuw, Mededelingenblad Vrienden van de Nedelandse Keramiek 64-65, The Hague, 1972

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1980

D.F Lunsingh Scheurleer, Chinesische und Japanishche Porzellan in Europäischen Fassungen, Braunschweig, 1980

Lunsingh-Scheurleer 1989

D.F Lunsingh Scheurleer, Chine de Commande, (2nd ed.), Lochem, 1989

Macau 2007

Pei 2004

Fang Jing Pei, Symbols and Rebuses in Chinese Art: Figures, Bugs, Beasts, and Flowers, Berkeley, 2004

Pinto de Matos 2003

Maria Antonia Pinto de Matos, Chinese Porcelain; in the Calouste Gulbenkian Collection, Lisbon, 2003

Chan Hou Seng (ed.), History of Steel in Eastern Asia - A View on the Development of Weaponry, Exhibition Catalogue The Macau Museum of Art, Macau, 2007

MacGuire 2023

Becky MacGuire, Four Centuries of Blue & White: The Frelinghuysen Collection of Chinese & Japanese Export Porcelain, London, 2023

Paris 1960 Collection de Madam L. Wannieck, Objets d’art de la Chine, Auction Catalogue, Paris, 1960

Pinto de Matos 2011

Maria Pinto de Matos, The RA Collection of Chinese Ceramic: A Collector’s Vision, Vol. I-III, London, 2011

Rastelli 2008

Sabrina Rastelli (et al.), China at the Court of the Emperors; Unknown Masterpieces from Han Tradition to Tang Elegance (25-907), Exhibition Catalogue Palazzo Strozzi, 2008

Rawson 1996

Jessica Rawson, Mysteries of Ancient China: New Discoveries from the Early Dynasties, London, 1996

Sargent 1991

William R. Sargent, The Copeland Collection, Chinese and Japanese Ceramic Figures, The Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, 1991

Sargent 2012

William R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Porcelain, from the Peabody Essex Museum, New Haven/London, 2012

74

Secreest 2004

Meryle Secreest, Duveen: A life in Art, New York, 2004

Seattle 2001

Robert Bagley (ed.), Ancient Sichuan: Treasures from a Lost Civilisation, Exhibition Catalogue Seattle Art Museum, 2001

Sheaf & Kilburn 1988

Varela Santos 2007

A.Varela Santos, Portugal in Porcelain from China, Vol .I-IV, Lisbon, 2007

Welch 2008

Patricia Welch, Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, North Clarendon, 2008

Colin Sheaf & Richard Kilburn, The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes, The Complete Record, Oxford, 1988

Simonis 2018

Ruth Sonja Simonis, How to Furnish a Palace: Porcelain Acquisitions in the Netherlands for Augustus the Strong, 1716-1718, Journal for Art Market Studies, Vol. 2 nr.3, 2018

Simonis 2020

Ruth Sonja Simonis, Microstructures of Global Trade: Porcelain Acquisitions Through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong, Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden, 2020

Ströber 2001

Zurich 1996

Roger Goepper (ed.), Das Alte China: Menschen und Götter im Reich der Mitte 5000v.Chr-220n.chr., Exhibition

Catalogue Kunsthaus Zürich, 1996

Eva Ströber, “La maladie de porcelaine…” East Asian Porcelain from the Collection of Augustus the Strong, Leipzig, 2001

Suchomel 2015

Filip Suchomel, 300 Treasures: Chinese Porcelain in the Wallenstein, Schwarzenberg & Lichnowesky Family Collection, Prague, 2015

75

76

For Bea van der Ven (1940-2023)

EDITOR, TEXT & RESEARCH

NYNKE VAN DER VEN-VAN WIJNGAARDEN MA

HEAD OF COLLECTIONS

FLORIS VAN DER VEN

RESEARCH & PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

VITA NAESSENS

CHINESE TRANSLATIONS

DR. MIN CHEN

PHOTOGRAPHY

THIS IS US | LEON VAN DEN BROEK PHOTOGRAPHY (OBJECTS)

IGOR SWINKELS FOTOGRAFIE

ROEL MARIUS BROUWER

CONCEPT & DESIGN

ORANJE BOVEN, ’S-HERTOGENBOSCH

PRINT

PRINTMAN, BREDA

A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO WOLFRAM KOEPPE, ALICE LEGÉ, AND KONRAD BERNHEIMER

VANDERVEN ORIENTAL ART

NACHTEGAALSLAANTJE 1

5211 LE ’S-HERTOGENBOSCH

THE NETHERLANDS

TEL: +31 (0)73 614 62 51

INFO@VANDERVEN.COM

WWW.VANDERVEN.COM

© 2024 VANDERVEN ORIENTAL ART, THE NETHERLANDS

Every object has a story to tell, if only we take the time to listen

COLOPHON

WWW.VANDERVEN.COM | @VANDERVENORIENTALART