39 minute read

CREATIVITY WORKSHOP

by vandieuap

Enthuse Your Muse

Do you ever feel like you’ve lost your groove as an artist? These tips can help you get it back—and keep it.

Advertisement

By Jean Haines

Artists love painting. It’s in our souls. An ever-present hunger to create drives us with a sense of urgency to express ourselves in our chosen medium. But what happens when our motivation starts to fade or disappears entirely? It’s a real possibility. I’ve met many longtime artists who no longer enjoy painting as they once did, even though they had successful art careers. Is it possible to use up creativity?

I’m often asked how I keep motivated and stay inspired in my own art practice. I think I’ve been fortunate because I had the opportunity to study multiple forms of art. I began my career as a botanical artist and eventually developed my own painting style, which has continued to evolve over the years. Th is distinctive style and my general enthusiasm for the watercolor medium have led to a busy schedule of workshop teaching. Despite my hectic and exhausting schedule, however, I stay motivated by recognizing, then prioritizing and balancing my creative and personal needs.

BE REALISTIC

As artists we put so much pressure on ourselves to create. Th ere’s a huge amount of stress involved in having to meet deadlines for art societies, exhibitions, art galleries, even writing or teaching. While a heavy workload can be a good problem to have, it can also be overwhelming— aff ecting your very will to pick up a brush. If painting becomes a chore rather than a way to feed your passion,

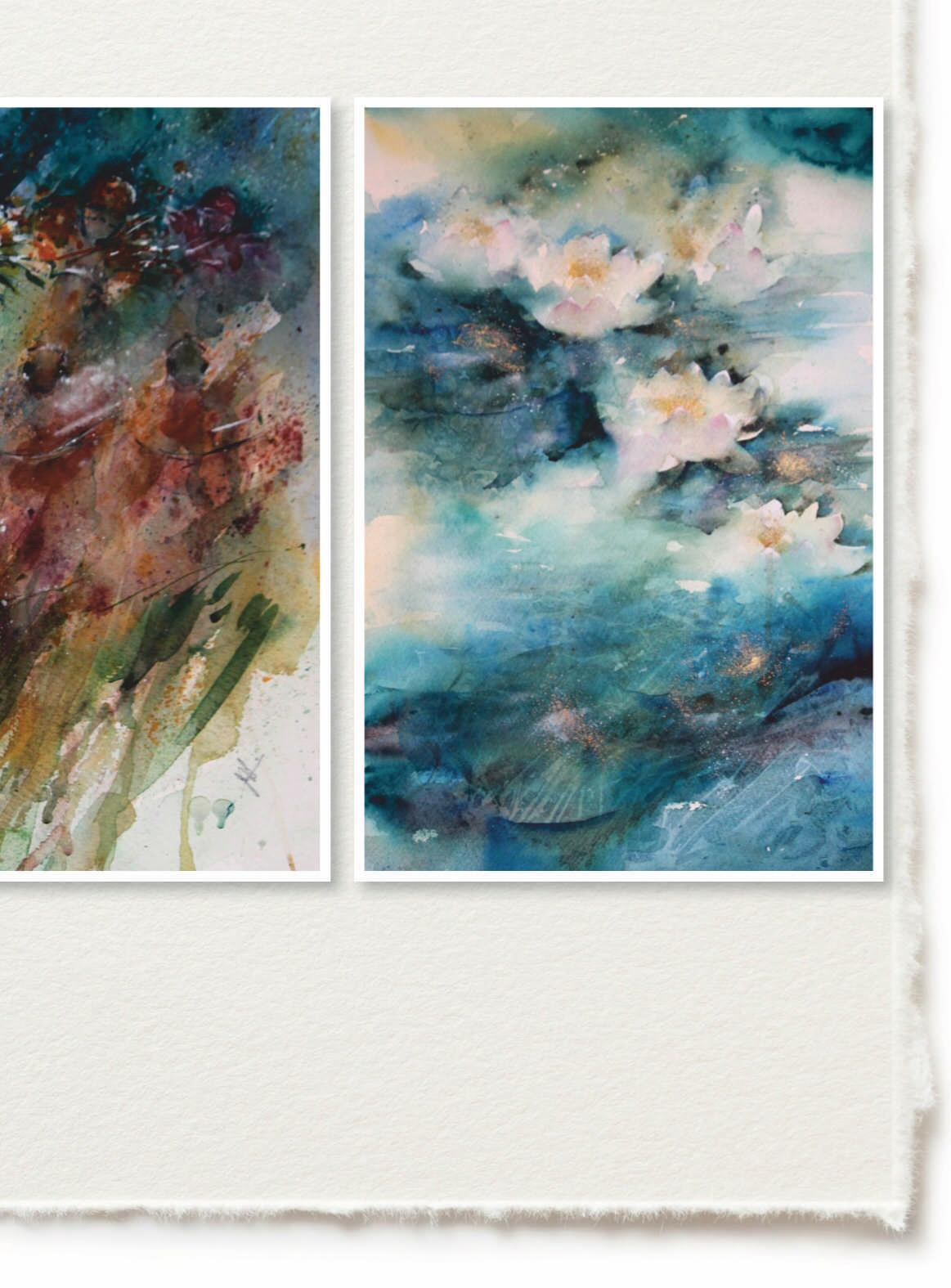

ABOVE LEFT

Racing Ahead

(watercolor on paper, 11x23)

ABOVE RIGHT

Monet’s Garden

(watercolor on paper, 23x15)

Creativity Workshop

the results will be refl ected in your work—and not in a good way. Don’t take on too much at one time or commit to deadlines that you know will add unecessary stress and pressure to your life. Approach painting, and your art career, in a way that suits your lifestyle. Be honest with yourself about what you can (and can’t) do. Set realistic goals and prioritize.

TRY SOMETHING NEW

Take a break from your regular routine and paint something completely diff erent every now and then. For me, this usually means creating abstracts, trying out products I haven’t worked with before or intentionally selecting colors I would normally avoid. Th is element of adventure always takes me right back to the beginning of my art career when everything was new and exciting. Th e heady feeling of not knowing what might happen stays with me when I return to more familiar ways of working, and I often gain knowledge that can be applied to my new compositions.

BE SELFISH

Set a period of time during which you slow down and paint something for yourself, just because you want to. It doesn’t matter what the subject is or which medium you use—just as long as it’s something you look forward to painting. Make yourself fi nish the piece within a predetermined time limit. Th at way you’ll feel like you’ve achieved something, even if you only painted for 30 minutes. After all, any time spent painting to get your motivation back is better than not painting at all.

STAY CONNECTED

Even if you genuinely don’t feel like painting, that doesn’t mean you have to stop enjoying art. Th ere are so many ways to stay connected with your craft, whether looking at artrelated sites online or visiting art galleries and museums. Take some time to study the Old Masters, or explore what’s

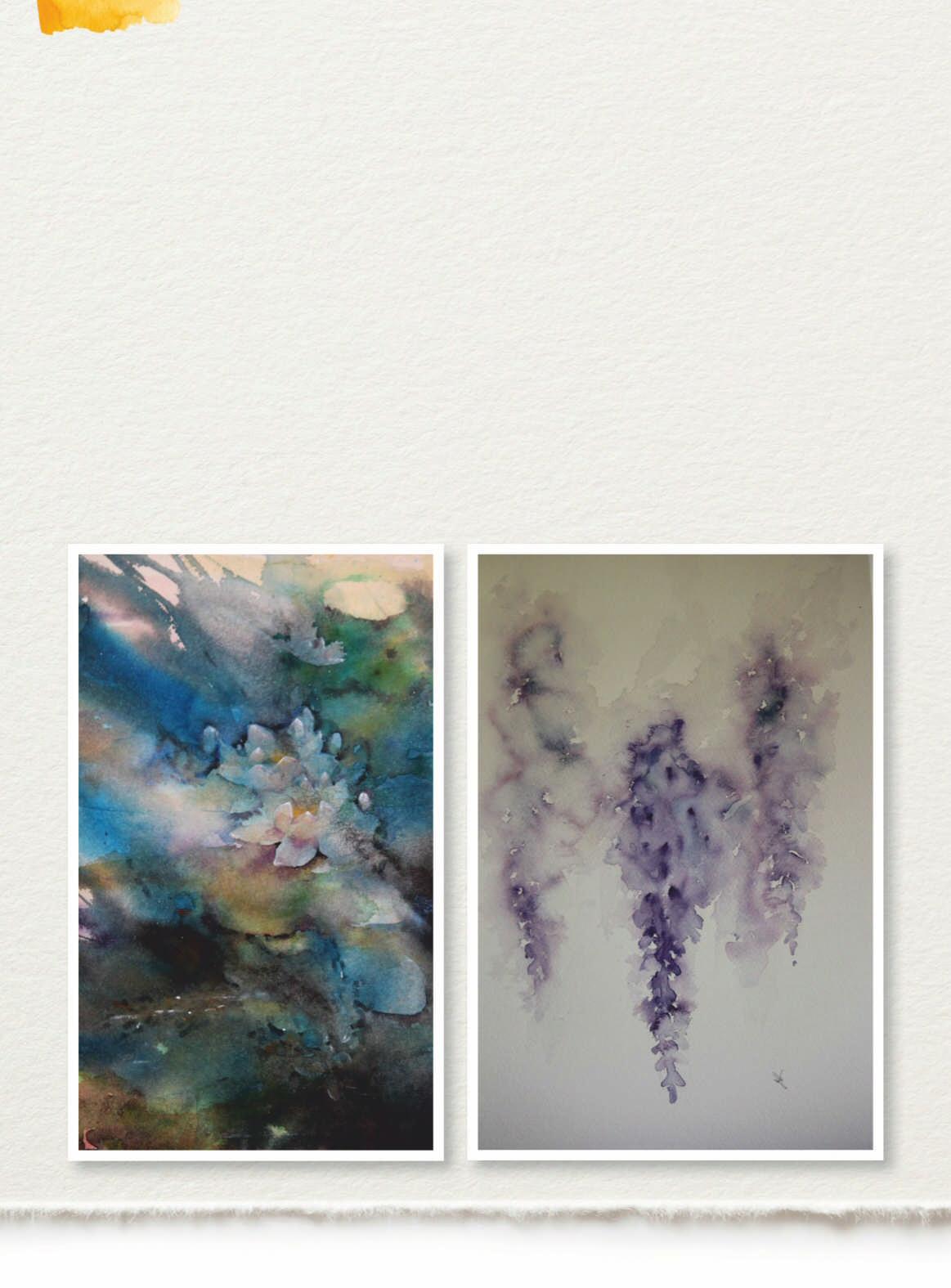

OPPOSITE

Hypnotic

(watercolor on paper, 15x11)

BELOW LEFT

Water Lilies

(watercolor on paper, 15x11)

BELOW RIGHT

Whispering Wisteria

(watercolor on paper, 23x15)

new in the art world. Learn how other artists create and let their passion reignite your own. You’ll begin to feel frustrated again, not about a lack of motivation but about not having enough time to paint.

GO EASY ON YOURSELF

So many of us are guilty of putting everyone and everything else in front of our own needs. It took me years to realize that I have choices. If I’m too busy or too tired to create, there’s only one person responsible— myself. Never feel guilty about how or when you pick up your brush, but try to fi nd a way to paint so that each creative session is quality time spent achieving results you can feel proud of. I emphasize the word “you” for a reason. Your time matters. Your well-being matters. You matter. WA

See more of Jean Haines’ work at jeanhaines.com or visit her online art school at watercolourinspiration.com.

Try this at home

WRITE AN ADVICE COLUMN FOR OTHER ARTISTS.

I can honestly say that I wouldn’t change my career in any way, shape or form. I love what I do and am so passionate about painting that I wake each day eager to start creating in my studio.

I try to follow my own advice and keep my enthusiasm high, always. This positive attitude has flowed into every aspect of my life. It even prompted me to write two books on the subject: Paint Yourself Calm (Search Press, 2016) and Paint Yourself Positive (Search Press, 2019). Those projects were a huge leap of faith for me, but they’ve found their way to many readers.

Now imagine that you have to write a column offering other artists tips on how to stay motivated. What would your most valuable advice be? Then listen to yourself and follow your own advice.

International Best Selling Author and Artist, Jean

Haines’ unique way of teaching has seen her successful International Workshops and Tours consistently sell out well in advance. Now you too can learn from one of the worlds’ most sought aft er art teachers. Be amazed at the original artwork you can create as a result of her fascinating tutorials, in this dynamic online learning center.

JOIN NOW via watercolourinspiration.com using the Special Promo code to receive a 10% discount.

Monthly: $19.99 $17.99 (code WATERCOLOR-ARTIST) Annual: $199.99 $179.99 (code WATERCOLOR-ARTIST-M)

Jean’s motivational books are available through Search Press, from leading art stores, book stores and Amazon.com

Follow Jean’s exhibitions and art events on her website www.jeanhaines.com

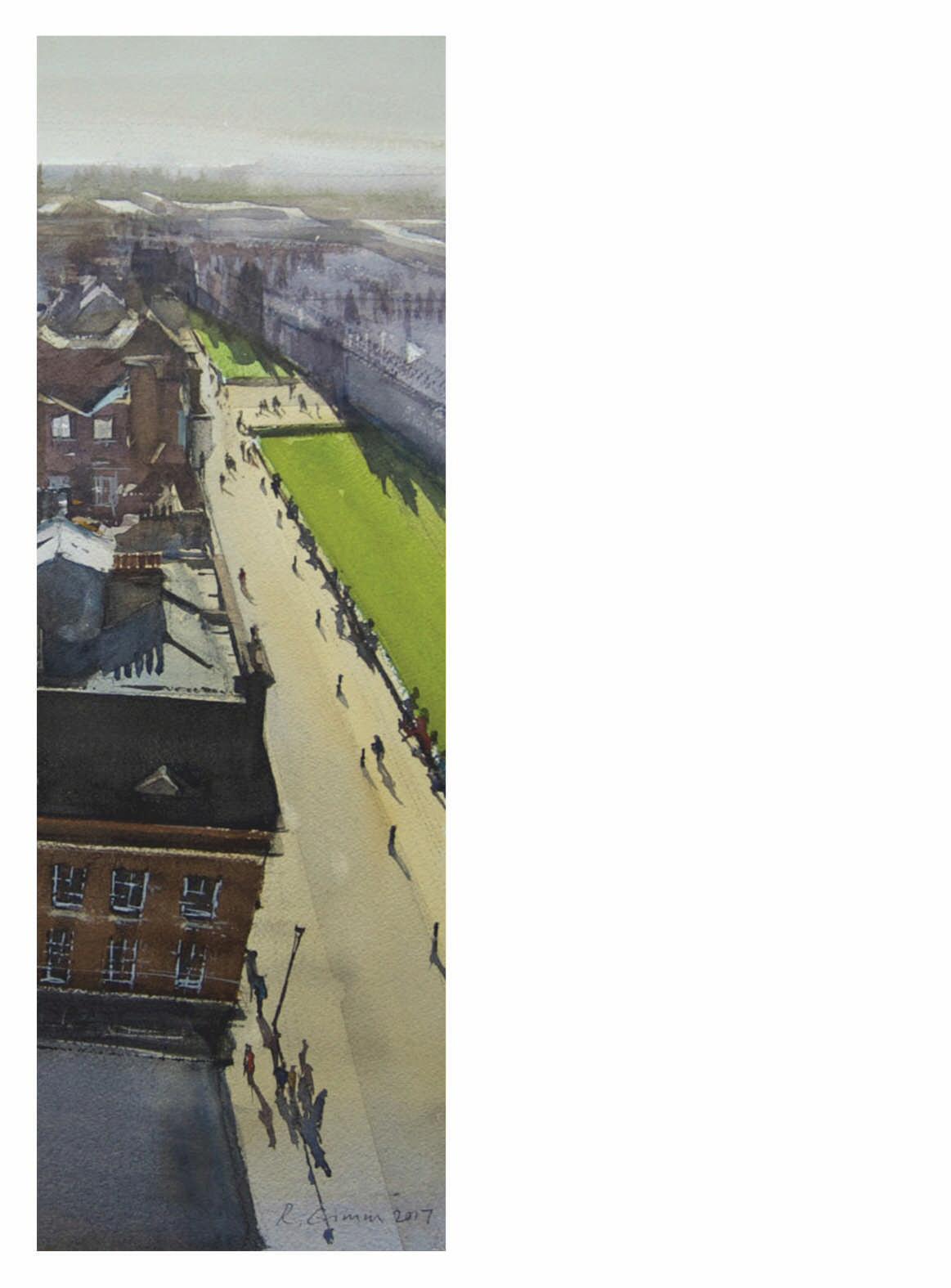

Bridge Street, City Island, The Bronx

(watercolor, 15x18½ ) R achael Grimm grew up in a village outside of Liverpool, in England. She lost her mother when she was 12. Her father, despite having to raise the family on his own, made time to support her artistic interests by providing her with an abundance of art materials. An avid drawer, young Rachael enjoyed copying illustrations from books and creating imagined portraits of the characters. Today, as a mother of three, she continues the tradition with her youngest daughter.

Despite her early leaning toward art, Grimm chose to study English literature and art history when she attended the University of Glasgow. At the time, she felt an academic degree would be more useful but hoped to paint in her spare time. One year, she became an exchange student at the University of Toronto, where she met her future husband, Stephen, who is American. During her fi nal year at Glasgow, the couple became engaged and, after graduation, moved to New York.

Eager to to get back to making art, she enrolled in fi gure classes at the Art Students League of New York, where she fi nally realized she wanted to be a professional artist. But a series of life events, including raising a family and a move to Indiana so her husband could work on his doctorate, put those ambitions on hold for a while. It wasn’t until they moved to Providence, R.I., where Grimm took her fi rst watercolor class at the Rhode Island School of Design, that she found her path back to art. Although she thought the medium diffi cult, she fell in love with it. “I liked the way it felt, and I knew I would come to grips with it one day.”

In 2008 the family moved back to New York, to a beachside town in Westchester County. With her youngest daughter in kindergarten, Grimm suddenly found herself with a lot more free time. She converted a spare bedroom into a studio and started enjoying the benefi ts of the local art community.

Since then, she has been showing, selling and winning awards with organizations such as the American Watercolor Society, the National Watercolor Society and Allied Artists of America. As an adjunct instuctor at Fordham University, she teaches a course on watercolor techniques, where she’s also preparing to teach the class online. “My studio has become a space for recording video demos and Zoom sessions. I’ve learned some very useful skills, and it has helped me to be more articulate about the skills I teach,” Grimm says.

A Comfortable Studio

Grimm’s studio occupies the middle story of her three-story house. “In this room I can be as tidy or messy as I like. When I’m there, I immediately go into an artist’s frame of mind. With three teenagers in the house, I often have my ‘mom hat’ on, but in my studio, I can just be an artist.” Windows placed south and east bathe the studio in sunshine all day. So much light, though, can

be a detriment. “Sometimes it’s too bright for me to see color accurately,” she says, but good paper blinds fi lter out the bright light as needed. “I always paint during the daytime, usually in the morning, so I never need artifi cial light.” If she’s painting a portrait or a still life, she closes blinds on all but the east window for a more dramatic, less diff used light.

Tools: Paper, Brushes and More

Grimm’s main work surface is a drawing board that rests on a John

Boos work table, which has a butcher-block surface, plus a shelf beneath for storage. Besides the drawing board, the table hosts a John Pyke palette with a large, rectangular mixing area edged by a number of wells for color, a roll of watercolor brushes and other miscellaneous tools. For portraits or still lifes, she prefers a large, upright studio easel, and for painting outdoors, a Winsor & Newton aluminum watercolor fi eld easel.

Like many watercolorists, Grimm is a fan of Arches paper, noting that it can take a beating and is a pleasure to work on. “When I’m teaching, I use student-grade paper because of the expense. As a result, I appreciate the better paper even more when I get back to using it for my own work,” she says. She tells students that if they become serious about watercolor, they should use the best quality

OPPOSITE

At the Breakfast Table

(watercolor, 19x13)

BELOW

Homework on the Porch

(watercolor, 16x23)

CULTIVATING CREATIVITY

Since moving to Larchmont, NY, Grimm has become interested in gardening. Daydreaming in the winter about what she will plant in the spring is, to her, akin to painting. “Creating a garden is a lot like composing a painting in that you have to think about structure, color and variety. Tending to it and helping it thrive is also a great complement to my time spent painting in the studio—just when I’m getting frustrated with a tricky painting, I can walk out into my back yard and lose myself in flowers,” says the artist. It’s a welcome change, and a welcome enrichment for her art, as well.

paper they can aff ord. “Using good paper takes a lot of the frustration out of watercolor painting, and the fi nished painting is always better.”

Although Grimm may experiment with unusual formats, she usually starts off with 22x30 sheets of 140- or 300-lb. Arches bright white paper, or 18x24, 140-lb. paper blocks. (She prefers cold-pressed paper.) She has a large roll of 156-lb. Arches paper for larger paintings, but she’s reluctant to use it because it must be stretched beforehand.

While she prefers professional-grade Winsor & Newton watercolors, Grimm uses other brands as well. “But I fi nd Winsor & Newton paints are reliable. It’s important to know that my paintings will look the same years from now, and I know this paint will hold up,” says the artist.

Grimm considers brushes to be some of her most important tools. Her inventory includes two Isabey Siberian blue squirrel quill mop brushes (Nos. 12 and 8) that have held up for years. She has a 1¾-inch Ron Ranson goat hair hake brush from Pro Arte that she fi nds useful for large washes. Recently, she has fallen in love with inexpensive, long-handled Chinese calligraphy brushes. “Th ey hold lots of paint, and they keep their points. I put these to use more often than my sable brushes,” Grimm says. Th e most fun brush she owns is also one of the least expensive, a synthetic sword liner by Pro Arte. “My students love to play around with it, and it’s my secret weapon for painting trees,” she says.

Letting Watercolor Do Its Thing

Grimm fi nds inspiration in simple, everyday things and the mood of a passing moment. Beach houses, hydrangeas and village streets are all subjects that occupy her paintings— as do people. “I love to paint my family going about their daily lives and places that I know well,” Grimm says. “Th e years are fl ying by so quickly.”

She often paints landscapes from reference photos, at times pasting several together to get the right eff ect.

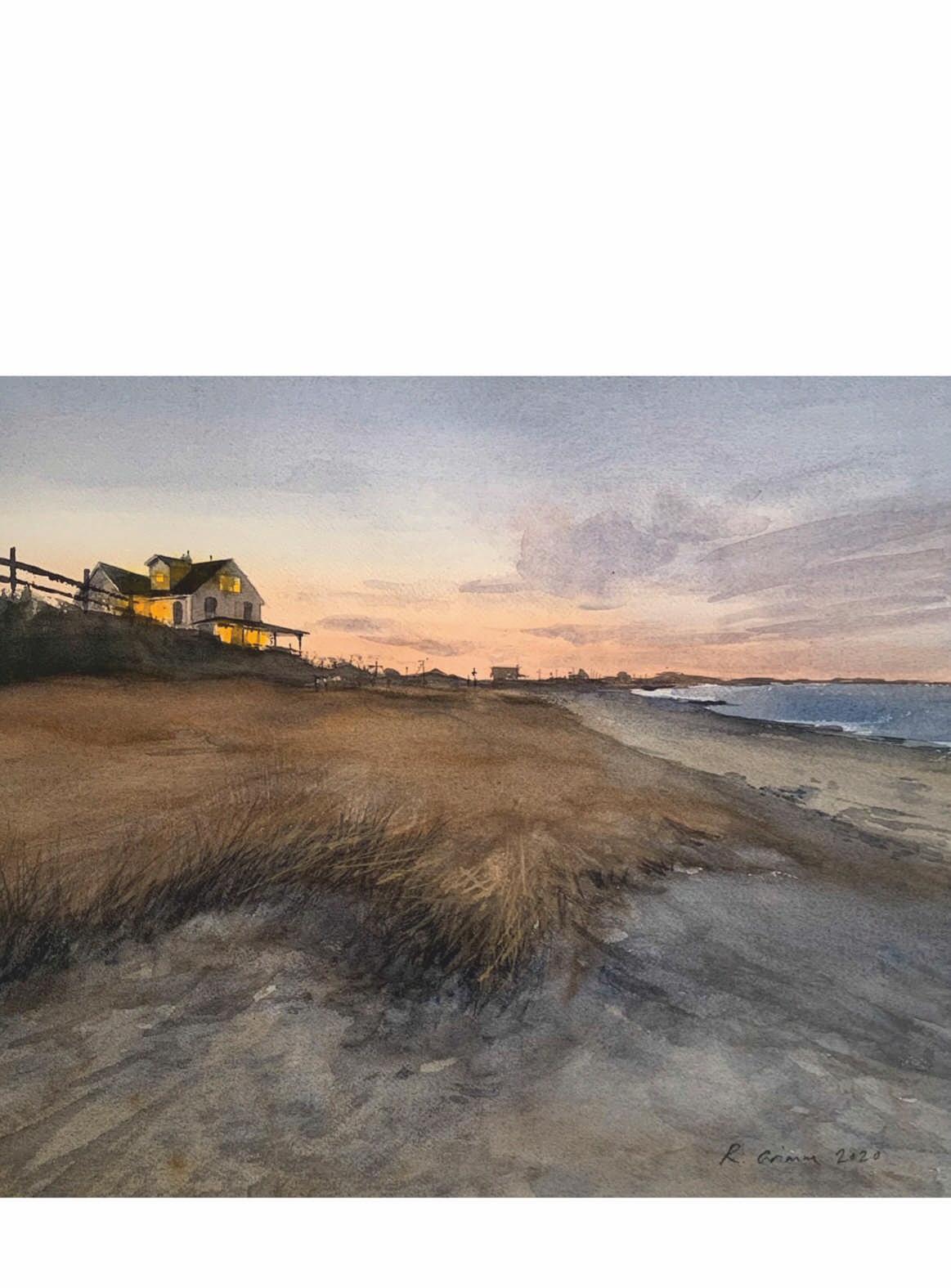

She prints the photos in black-and-white and, before starting a painting, often makes a color study based on these and notes from her sketches. Her still lifes start from life, but if she can’t fi nish a painting in a few hours, she’ll take a photo and work from that. Even before putting brush to paper, Grimm spends a great deal of time exploring ideas in a series of thumbnail sketches, often while resting on her studio couch. “If the composition isn’t right, no amount of good painting will make the piece work,” she says. Still, she doesn’t shy away from changing horses in mid-stream. “If I’m in the middle of painting and something doesn’t look right, I’ll use a viewfi nder to play around with cropping.” She did this with her painting King’s Parade, Cambridge (left), which was originally twice as wide. Grimm considers color and tonal values to be just as important as design. “Beyond subject matter, capturing the quality of light is a powerful way to express the mood of a passing moment,” she says. Particularly poignant to her is the mood evoked by twilight, which she depicts in her painting Th e Beach is Closed (opposite), a piece inspired by an evening with her children at the beach. To create these expressive eff ects, she often starts a painting with loose washes of paint, letting watercolor “do its thing.” Th ese fi rst layers, which contain only a tiny amount of pigment, are either fl at or graded washes. She often covers the whole sheet Grimm used a viewfi nder with these fi rst washes so that as an aid to adjust the they’ll shine through later layers, cropping in King’s Parade, Cambridge (18x6½ ), which was unifying the whole. Preferring not to use masking originally twice as large. fl uid, Grimm avoids areas she wants to keep as her lightest value. If they’re small areas, like highlights on leaves, she scribbles over them with a wax resist crayon to preserve them. “I’ve tried to do this with masking fl uid, but have found that wax resist works best for my purposes,” she says. Th e wax stays on the paper, becoming part of the painting. Also, though she tends to work in layers from light to dark, sometimes she has a feature that needs to be established early on, such as fi gures. Once these washes dry, she lightly sketches in shapes with a Derwent 2B pencil. But rather than form a detailed drawing, the lines serve as boundaries. “Th ey’re there to let me know where the paint can and can’t go.” Th en she dives in happily with big brushes, swirling around color, developing a sense of movement. Generally, she puts warm tones in the light areas and cool tones in shadows, pushing the contrast to convey mood. Sometimes, she drops paint right into the wet wash, as in the area of grasses in Early

Evening, Block Island (page 24).

As she moves to darker layers, the painting starts to resemble her original vision. She then adds more detail, as necessary, with smaller brushes. Finally, she runs a dry brush with just a touch of paint over areas to enhance the feeling of texture.

Like many artists, Grimm struggles to remember to stop when she’s ahead. “I’ve ruined more paintings than I care to admit through overworking them,” she says. “When I’m

–RACHAEL GRIMM

ABOVE

The Beach is Closed

(watercolor, 18x25)

LEFT

Late Afternoon at the Beach

(watercolor, 18x25)

following my own rules and trying to be as thoughtful as I can with my brushstrokes, things just seem to fall into place. If the full range of values is there, all it takes are a few fi nishing touches, and then I can put down my brush. Th is is easier said than done. Th e good news, however, is that I do learn from these experiences, and I do my best paintings—often quite quickly—after I have spent hours laboring over a bad one.”

An Alternate Medium

Besides watercolor, Grimm also works in charcoal. She fi nds it therapeutic to switch between the two. “For everything to go right for me in a watercolor painting, I really have to be focused. Even after years of practice, I still sometimes feel frustrated,” she says. For a break, she turns to more easily controlled charcoal. “I can just keep erasing and adjusting until it’s right.” She notes that one medium informs the other. In charcoal, she works from light to dark, with her lightest lights being the white of the paper, and just as she does in watercolor, she uses the full range of tonal values. “Th e fi rst stages of a charcoal piece are similar to my initial washes

OPPOSITE TOP Winter Flowers (charcoal, 15x23)

OPPOSITE BOTTOM

Winter Flowers

(watercolor, 17x21)

BELOW

Early Evening, Block Island

(watercolor, 15½ x18)

Meet the Artist

Rachael Grimm (rachaelgrimm.com) is an award-winning watercolor artist who grew up in the northwest of England and moved to the U.S. in 1996. She trained at the Art Students League in New York from 1996–2000, specializing in figure painting in oil.

In addition to watercolor, Rachael loves to use charcoal. Sketching from life has always been an important part of her art practice. She attends life-drawing sessions at the Spring Street Studio in New York and sketches and paints outdoors regularly.

Her paintings are in numerous private collections both in the U.S. and overseas, and one of her portraits is permanently installed in the main library at Fordham University.

in watercolor. Instead of paint, though, I grind up charcoal to a fi ne powder, spread it over my paper and rub it in until it’s the correct value,” she says. Th en, using willow sticks of diff erent widths, she builds up layers of charcoal, using the tips for details and the sides for broad areas.

As to which medium to choose for a particular subject, Grimm uses charcoal if she’s interested in structure but watercolor if she’s interested in light and color. “I’ve only done a painting and charcoal drawing of the same subject once (see Winter Flowers, above), but the things I chose to highlight in each piece were quite diff erent. I happened to have a jar of old hydrangeas sitting on a table underneath a window. Th e way the fl owers and glass jar caught the sun made me want to paint them in watercolor. After I fi nished, I was still interested in the structure of the papery fl owers and thought charcoal would be a great way to explore this. So my intention with the charcoal was more about wanting to do a detailed drawing than capturing the eff ects of light.” WA Michael Chesley Johnson is a Signature Member of the American Impressionist Society, the Pastel Society of America and the Pastel Society of New Mexico. He’s a long-time contributor to Pastel Journal and Artist’s Magazine.

BARONESS HYDE DE NEUVILLE RECORDED THE LANDSCAPE AND INHABITANTS OF THE EARLY 1800s HUDSON RIVER VALLEY WITH AN EQUALLY SHARP EYE AND SOCIAL CONSCIENCE. by C.J. Kent

s Napoleon’s armies came searching for resisters who sought to reinstate the Bourbon monarchy, Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny; the Baroness Hyde de Neuville (1771–1849) escaped with her husband on a ferry. Standing along the deck of the boat slowly moving upstream from her husband’s familial home, La Charité sur Loire, she painted. Th e watercolor and ink drawing of the lost estate implies a resilience that would hold her in good stead over the years to come. In due course, her husband was arrested for conspiring with enemies of the emperor. When her attempts to disprove the charges failed, in 1805 she pursued the French armies amid raging battles across Germany and Austria, accompanied only by her chambermaid, seeking an audience with Napoleon himself. She pleaded her husband’s cause to whomever would listen, painting as she traveled. She so impressed Napoleon that he permitted the couple to live exiled in

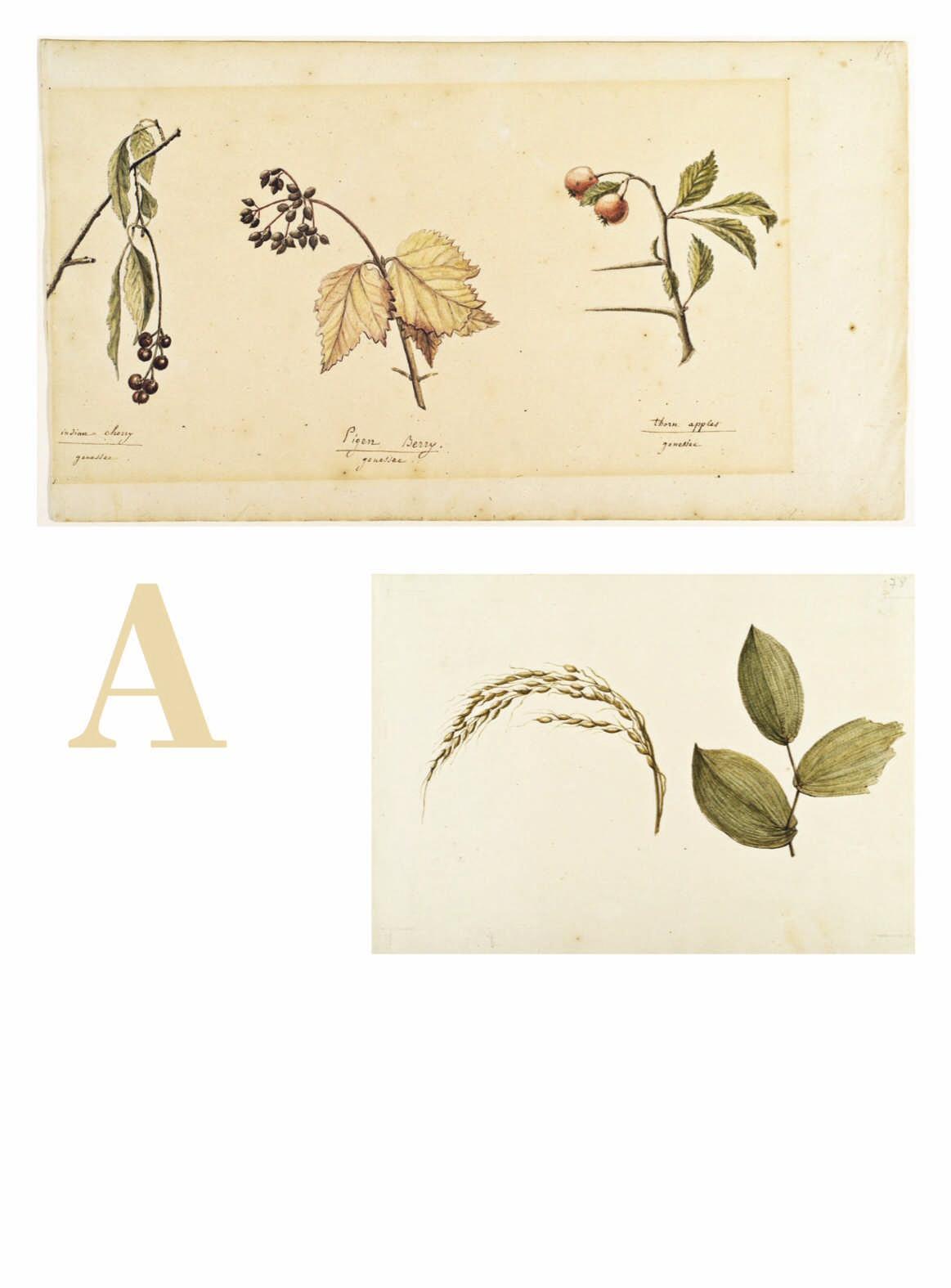

TOP TO BOTTOM

Studies of Fruit-Bearing Plants: Wild Black Cherry (Prunus serotina); Mapleleaf Viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium); Thornapple or Hawthorn (Crataegus species), Genesee, New York

1807–14; watercolor, graphite, black chalk, and brown and black ink on paper; 7¼ x13

Studies of Rice (Oryza glaberrima or sativa) and Leaves of the Sessile Bellwort (Uvularia sessiliforlia)

1807–14; watercolor, brown ink, black chalk and graphite on paper; 5¾ x8 OPPOSITE

Distant View of Albany From the Hudson River, New York

1807; watercolor, brown ink, black chalk and graphite with touches of gouache on paper

PREVIOUS SPREAD

Break’s Bridge, Palatine, New York

1808; watercolor and graphite with touches of white gouache, black ink and black chalk on paper

the United States. In 1807, the two arrived in New York. Th e Baroness’s watercolors provide thoughtful, honest depictions of the new world.

VIEWS OF THE VALLEY

Neuville would have used a wooden, hinged-lid pochade box that provided porcelain dishes, paint pots and a drawer to keep brushes and supplies. Th e quantity of her watercolor paintings indicates she almost always had the box with her. Drawing with pencil and watercolor was one of the arts instilled in young women of the 18th century, but Neuville seems to have dedicated herself to painting throughout her life, fi nding time for her avocation in spite of other demands.

Th e Neuvilles traveled to Niagara Falls during their fi rst year in New York. Admiring the lush landscape of the Hudson River Valley, the Baroness made careful watercolors long before William Guy Wall made the practice popular among artists with his Hudson River Portfolio, featuring hand-colored aquatints, the plates of which were produced from 1821 to 1825. Educated with the Enlightenment’s deference to the natural world, Neuville’s botanicals are beautiful studies of the new varieties of fl ora that she encountered (see the botanical studies on the opposite page). She valued fruit-bearing plants as much as simple geranium fl owers or the trunk of a fallen tree. Her landscapes are reminders of the densely vegetated land dotted with distantly spaced towns that made up the Eastern seaboard at the time (see Distant View of Albany from the Hudson River, New York; below).

Impressed by the engineering feats of the Hudson River Valley’s settlers, Neuville also painted bridges, fences and buildings (see Break’s Bridge, Palatine, New York; pages 26–27). Th e American wilderness was daunting, and

the drive to establish trade, commerce and Old World ways of life demanded industriousness. European visitors were often intrigued with the ways people found to overcome wild rivers and mountain chasms.

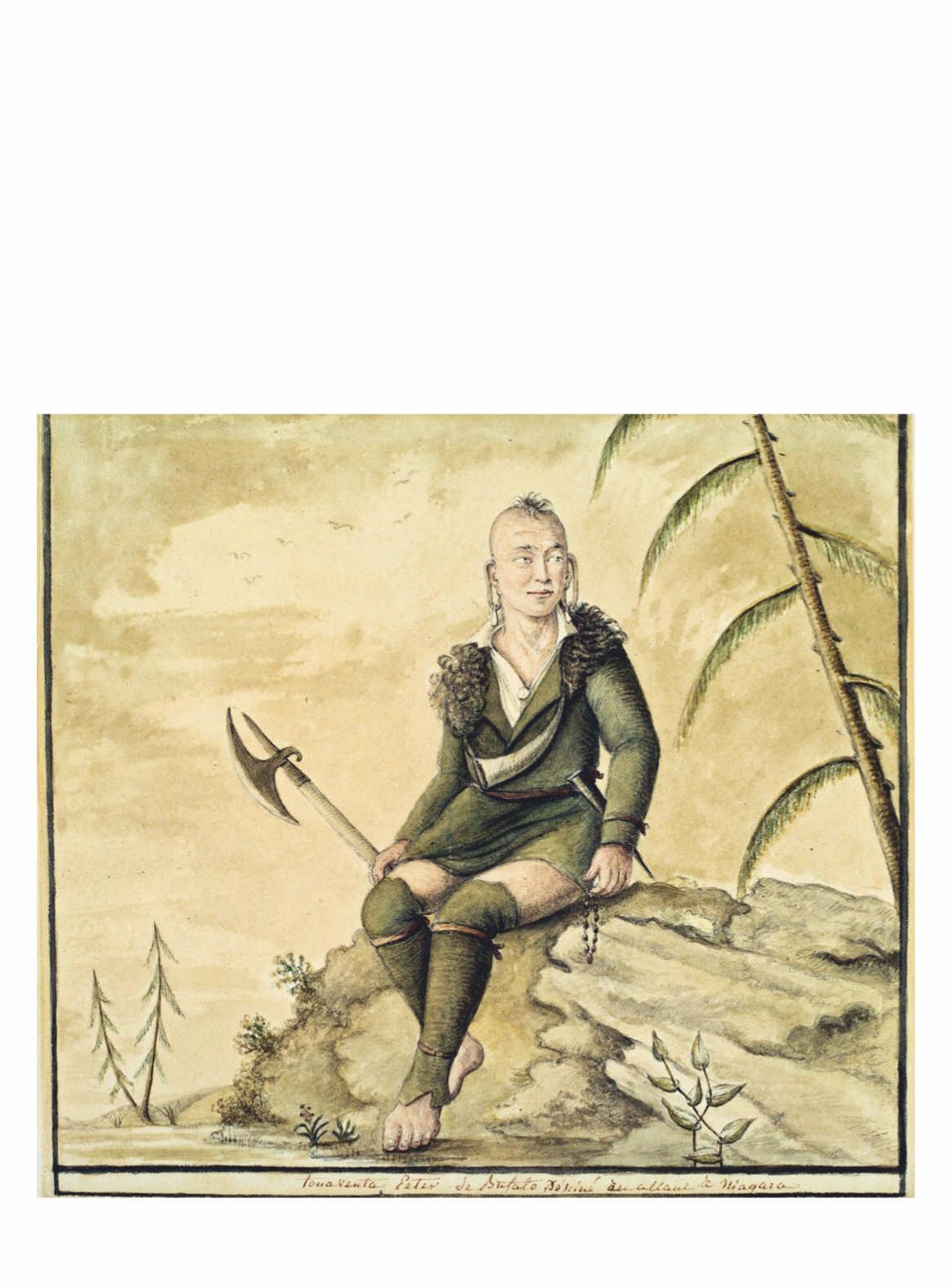

DIVERSITY PORTRAYED

While traveling, Neuville encountered individuals from various tribes and countries, including other émigrés from France. Th e Baron’s diaries indicate that the couple believed the United States to be a truly classless society, and perhaps that belief dispelled the infl uence of their aristocratic upbringing and allowed Neuville to see clearly the people she faced. Her watercolors are some of the fi rst ethnographically correct images of the Native peoples, many of whom agreed to sit for her. She met representatives of the Oneida, Mohawk and Seneca tribes, and always identifi ed her sitters by name and title. For example, the name of the painting Peter of Buff alo, Tonawanda, New York (below) identifi es a site on the Seneca Reservation. Peter was likely a Seneca tribesman, as evidenced by his lengthened earlobes and earrings, and recognizing his home was a sign of respect. His clothing and accessories,

Peter of Buffalo, Tonawanda, New York

1807; watercolor, graphite, black chalk and brown and black ink with touches of gouache on paper

Martha Church, Cook in “Ordinary” Costume

1808–10; watercolor, graphite, black chalk, brown and black ink and touches of white gouache on paper

however, indicate a life partly infl uenced by the settlers. His undershirt and gartered leggings are European, but his fur and tools—a trade ax known as a “halberd tomahawk,” a knife, a powder horn and a string of wampum—are attributes of his tribe’s way of life.

Neuville’s works include formal portraits as well as depictions of people working, sitting, reading, writing and painting. A portrait of artist Louis Simond (1767–1831), with a palette to denote his vocation, honors her mentor; however, the artist was respectful of all her subjects, regardless of their social or vocational standing. Th ere’s a sense of stillness about these portraits, yet Neuville captured her sitter’s attitude and personality. Her painting Martha Church, Cook in “Ordinary” Costume (left), depicts a woman wearing her workaday clothes and looking as if she’s ready to return to her duties in the kitchen. Th ere’s a similar sense of restlessness in Young Girl in Full or Fancy Dress, (page 32).

Neuville’s interest in people was indefatigable, and her watercolors, delicate and sincere, suggest that she was a woman who, unlike many of her day, felt comfortable in all company and knew how to make others feel comfortable, too.

Young Girl in Full or Fancy Dress

1809–15; watercolor, graphite and black chalk with touches of brown and black ink and red gouache on paper

SOCIAL CONSCIENCE AND ACUTE CURIOSITY

After the Hudson tour, the Neuvilles settled in New York City, where they found an active French community. Th e artist’s watercolors of the city during that period provide a vivid sense of the street life, the nature of the neighborhoods and the diversity of the population. She became actively involved in the Economical School, an organization founded to provide basic lessons to fugitives from the West Indies and other French emigrants. Drawing was part of the curriculum as it advanced one’s observation of the world. Th e school was also a place that cared for poverty-stricken children, both boys and girls. In fact, Neuville was an avid proponent for gender equality, even expressing her desire to see “an American Lady elected President” in 1818, when she was in the country’s new capital of Washington, D.C.

In 1814, with the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, Neuville and her husband returned to France but traveled again to the United States in June 1816. Th ey endured a 29-day stormy crossing so that the Baron could assume diplomatic duties in Washington, D.C. as minister plenipotentiary. Neuville’s watercolors aboard the Amigo Protector reveal her fascination with nature and utter lack of squeamishness. Her painting Study of Two Sea Creatures (Aboard the “Amigo Protector”), opposite, of two organisms crawling over one another reveals an open curiosity. Once in D.C., her husband’s duties required that Neuville turn much of her attention to the hosting of political dinner parties and gatherings, but she still found time to paint the growing town and its visitors.

INVALUABLE RESOURCE

Neuville’s works off er a poignant reminder of watercolor’s important role before the invention of photography. Th is was the medium used to capture daily life. Watercolors off ered the speed that allowed busy people to agree to sit for a portrait, but it’s in the care of the strokes that the

Learn More This article is based on works presented in the New-York Historical Society’s 2019–2020 exhibition Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville. Learn more at bit.ly/ neuville-exhibition.

ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Study of Two Sea Creatures (Aboard the “Amigo Protector”)

watercolor, black chalk, brown ink and graphite with a touch of gouache on paper; 5⅜ x7⅛

painter’s attitude toward her subject becomes evident. Neuville, for all her wealth and bearing, shows an equal interest in the lives of all men and women that asks us to reconsider our historical imagination. She used paint with a fair and equalizing eye to celebrate who and what she encountered in her life. Th ese simple images, many of which are in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, invite artists today to reconsider the advantages of watercolor painting. If a Baroness could do it aboard ships on stormy seas and as a dignifi ed political guest in a foreign nation, what new insights might a watercolor artist bring to the world today? WA C.J. Kent is a freelance writer and editor, as well as a professor at Montclair State University. She also founded Script and Type (scriptandtype.com), which helps people express themselves eff ectively in writing and in person.

Self-Portrait

1800–10; black chalk, black ink and wash, graphite and Conté crayon on paper

SOJOURN TO ITALY

Four watercolorists heed the call to a country beloved by artists—and each has a unique creative response.

BY COURTNEY JORDAN

The scenic beauty and rich culture of Italy have called to artists for centuries. The country’s historic cities and idyllic countryside, its famed architecture and museums, its hidden side streets—each of these features is alluring in its own way. Each overflows with inspiration for visiting artists.

Here we feature four watercolor painters who have found an artistic connection to Italy. They take the country’s sights as their muse, although each artist interprets those sights in a different way. Peter Carey opts for a variety of styles in his depictions of the Italian cityscape; David R. Smith spends much of his time gathering the bellissima of Italian cities through his camera lens; Anne McCartney embraces a new interpretation of the country every time she visits; and Tim Wilmot celebrates the plein air paradise of Italy while keeping his paintings grounded in reality.

Though you may not be booking international travel at present, the visual interpretation and storytelling that this quartet of artists share is armchair traveling at its best—a virtual holiday for the present and inspiration for future visits.

PETER CAREY

AN ARTIST’S WONDERLAND

ITALY’S CITIES and all the history they contain call to Peter Carey (petercareypaintings.com) most of all. “Th e churches and monuments, galleries, cafés and city lifestyle are what appeal to me,” says Carey. “You can turn a corner in Rome and see something built 2,000 years ago. Likewise, in Florence, you can see buildings that the Medici commissioned. To me, as a photographer and painter, Italian cities are my Disneyland.”

But bombast and magical whimsy don’t drive the artist’s work. Carey’s art is quite factual and unsentimental, slices of life that he presents ‘as is.’ “Th at’s an extension of my personality,” he says. “I had eight years of English private schools, and they purged sentimentality out of me. I fell into a style of painting that worked for me, and it happened to be a factual or realistic style. All my paintings have meaning or sentiment for me. I just hope that others can connect. Sometimes that’s just luck.”

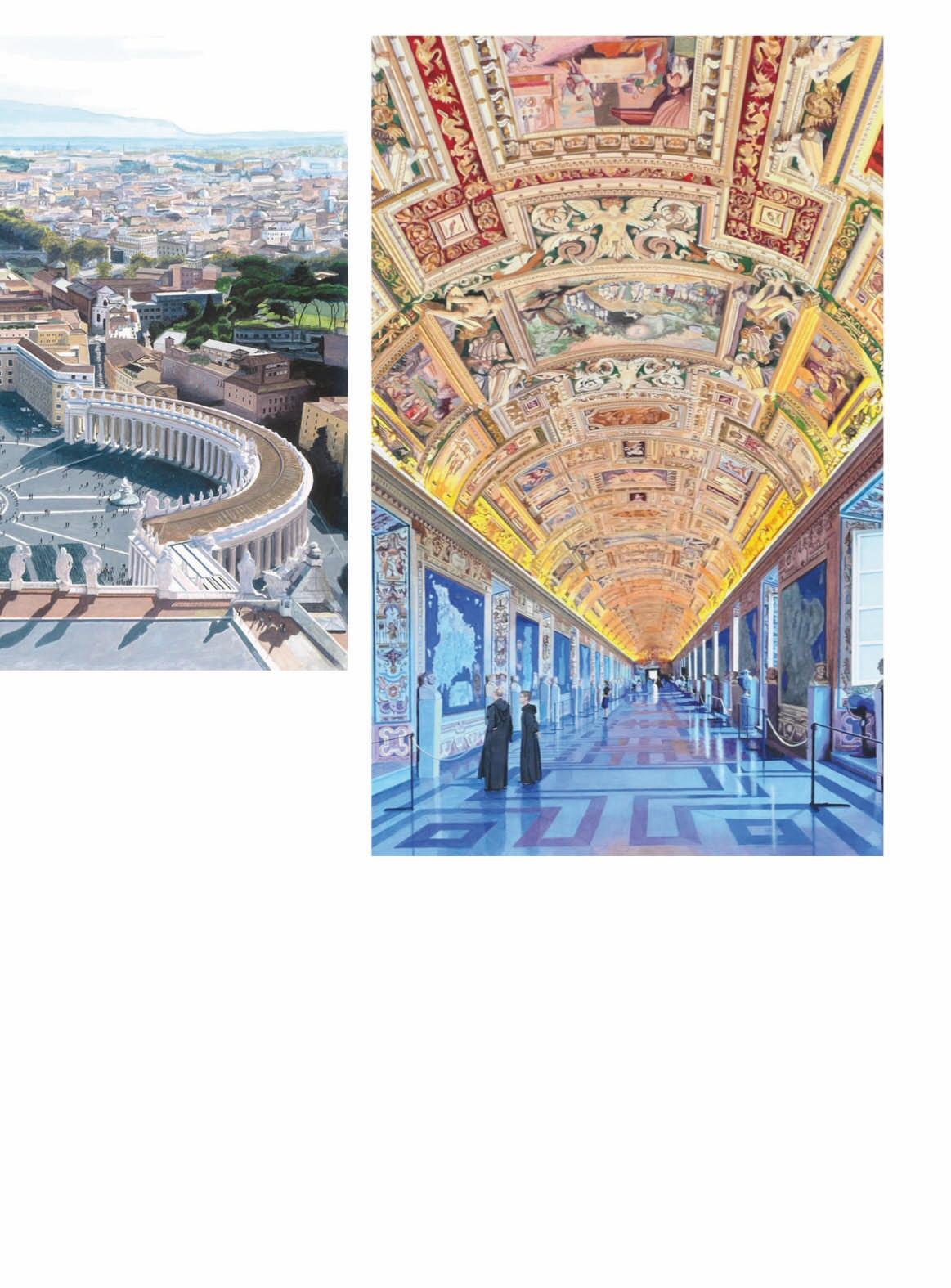

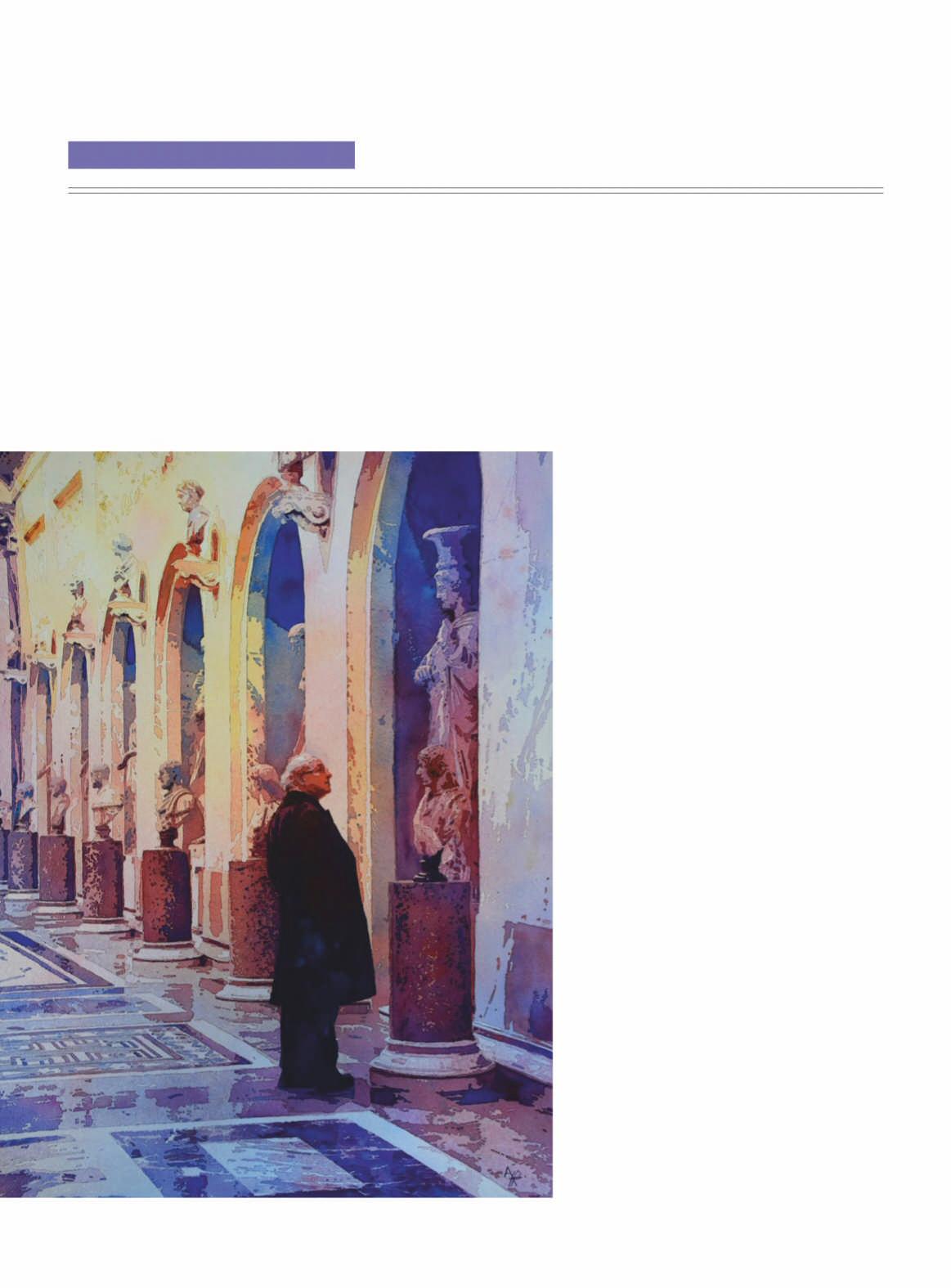

Carey’s depictions of the plaza in front of St. Peter’s Basilica (see St. Peters Square, above) and the nearly 450-yearold Gallery of Maps (see Gallery of Maps, opposite) are

a refreshing change from the postcard or souvenir images of these famous cultural landmarks in Vatican City. Th e process to arrive at these deliberately unromanticized works is not one that happens on site. When in Italy, Carey paints from a small, portable watercolor set, but usually in hotel rooms from photos, as he’s not primarily a plein air painter. Most often, though, he takes what he has seen in Italy back to his home studio in California to be worked into watercolor creations.

For Gallery of Maps, Carey started with a reference photo he’d shot that captures a quiet moment at the Vatican museum. “Early morning is the only time of day when the site isn’t guaranteed to be fl ooded with crowds,” he says. He combined several references: photos he took coupled with images he sourced from the internet of the ceiling paintings. Th e two priests in the painting aren’t in any of the reference images of the Vatican. “I took that

photo in Santa Maria del Popolo and dropped the priests into the Gallery of Maps,” says Carey. “Artistic license!”

Carey goes on to note, “It took me several months and hundreds of hours to paint Gallery of Maps, but the colors were so saturated, I didn’t get bored. Th e yellow of the ceiling comes from the artifi cial light, and the blue light on the fl oor comes from the natural light of the windows.”

St. Peter’s Square is the result of a photo taken after a walk to the top of the dome of St. Peter’s—something few people know they can do. “My wife and I have climbed to the top several times,” says the Carey. “Often you can’t see the hills in the distance, but one day the air was beautifully clear. Most of the landmarks are in the right places. I may have moved some apartment buildings around. Th e wonderful thing is that now I appreciate this part of Rome much more for having painted it.”

ABOVE LEFT

Saint Peter’s Square

(watercolor on illustration board, 12x20)

ABOVE RIGHT

Gallery of Maps

(watercolor on illustration board, 22x14)

DAVID R. SMITH

DEFINITELY NOT MINNESOTA

THIRTY YEARS AGO David R. Smith (dsmithfi neart.com) and his brother were treated by their grandmother to a tour of Italy organized through a local art guild. “It was a two-week whirlwind of ancient architecture and art to be enjoyed along with the busy cities and beautiful hill towns,” says Smith. “Th e experience inspired me artistically and fueled my desire to explore more of Italy and the world; however, what struck me most on my fi rst trip was that Italians didn’t have screens on their windows! If I did that in Minnesota, the mosquitos would fl y in and carry me off .”

In 2012, Smith decided to take his watercolor painting more seriously and embarked on a nine-week European

trek—passing through Italy three times. Th is experience set the tone for how he would approach all the visits he would make to Italy thereafter: with camera to eye, ready to capture all the paint-worthy scenes that came into view. “I was after the countless subjects that could be turned into attractive watercolors—ancient Roman ruins decorated with timeworn statues, vistas of couples walking through narrow alleyways, ports with colorful boats against a backdrop of majestic mountains. My trigger fi nger became numb from the almost nonstop clicking of the camera shutter.”

Th e result was a treasure trove of photos and inspirational memories for the artist. Using those photos, Smith

ABOVE

Lights of Florence

(watercolor on paper, 22x30)

OPPOSITE

Shower of Light

(watercolor on paper, 22x30)

Lamentation

(watercolor on paper, 22x30)

has painted more scenes of Italy than of any other country, but he looks forward to capturing those scenes in person as well. “I do feel a little intimidated by the long list of exceptional artists who have painted there before me,” he says, “however, I’m defi nitely in Italy to view and interpret the country on my own terms.”

As Smith explores with his camera, he’s constantly on the lookout for compositional elements that will allow him to develop a striking painting. Among these he cites “strong shapes with interesting action lines, such as those of ancient cathedrals with spires adorned with statues; the diff erent moods created by light and shadow, with light streaming through high windows or cast across a dramatic sculpture; and the interesting juxtaposition of tourists and taxis against ancient architecture.”

What Smith doesn’t mention, perhaps because it’s intrinsic to his process, is color, yet color holds much visual power in his work. Paintings like Shower of Light (opposite) feature architecture that seems to be built not of marble and stone but of prismatic color. Th e statuary in Lamentation (above) is bathed in stained-glass color.

When I commented to Smith on his use of color, he said, “Th is reminds me of other comments I’ve heard: ‘Is that a watercolor? I didn’t know watercolor could have such strong color.’ As one of my fi rst watercolor instructors, Gordon MacKenzie, said, ‘To have professional results, you need to use lots of pigment and a big brush.’ I also attribute the clean colors to my letting them mix on the paper.”

Smith showcases several styles in his Italian paintings. Some works, such as Lights of Florence (left), are full of high drama; others show more of a slice-oflife. “Working watercolor wet-into-wet, one fi nds it has a life of its own and rewards the artist with unique textures and an intermingling of colors,” says Smith. “One reason for my variety in style and subject is that I paint, in part, to learn more about this versatile medium and what I’m capable of producing. Th e more I learn, the more I can share. In my pursuit of becoming the best artist and teacher I can be, I stay open to the journey of discovery.”

ANNE McCARTNEY

LAND OF MEMORABLE MOMENTS

ANNE MCCARTNEY (mccartneyartworks.com) possesses a relationship with Italy built on the power of fond memories and observed moments accumulated over the course of a lifetime. Having visited Italy as a child, a student and a parent with her own children, McCartney’s connection to the places and people of Italy are born anew with every trip. “My visits were far apart, and I was at diff erent stages of my life each time,” she says. “I experienced it for the fi rst time, each time.”

A general sense of wonder and joy underlies most of McCartney’s recollections of Italy, although she says that

most of the memories are mere “snatches of moments— seeing Michelangelo’s David for the fi rst time, the awe of the Sistine Chapel, the deliciousness of gelato …” Th at sense of the momentary extends to her work as a visual artist.

“When I paint people, I want them to be relatable, to have a narrative. In Italy, people enjoy being in the streets, in the cafés and just out in the piazza visiting with friends and catching up,” says McCartney. She showcases that social spirit in her painting Problem Solving (opposite). “People walk to their destinations, so there are many more people out and about. It makes it easy to capture moments of ordinary people going about their lives and then create paintings from those moments.” Th e painting An Admirer (left) was developed in just such a way. McCartney, visiting the antiquities in the Vatican Museum, spotted another sightseer taking advantage of a rare moment in a quiet and empty gallery hall to closely observe marble sculptures along the wall. “I couldn’t help but wonder what he was thinking as he contemplated these works of art,” she says. “I thought that his admiration and contemplation would make a wonderful narrative. I liked the idea of creating a new piece of art from someone appreLEFT ciating something ancient An Admirer (watercolor on and historic.” paper, 29x22) When McCartney elects to paint architecture, she OPPOSITE comes at it diff erently, Problem Solving (watercolor on paper, 22x15) sidelining the human element so it doesn’t become the focal point. “I paint fi gures without faces and abstract the body so that it becomes secondary to the building,” she says. In that way the architecture of the Italian cityscape—the “old souls,” as McCartney calls them—can claim the lion’s share of a viewer’s attention. Th e results are uniquely still moments around a city’s celebrated architectural features that usually brim over with sightseers and visitors. “Italy is very much about the hustle and bustle of tourism,” says McCartney, “but there are opportunities for serenity, moments when you can fi nd yourself alone and able to contemplate the beauty around you. To be intimate with your surroundings is very much a luxury.”

TIM WILMOT

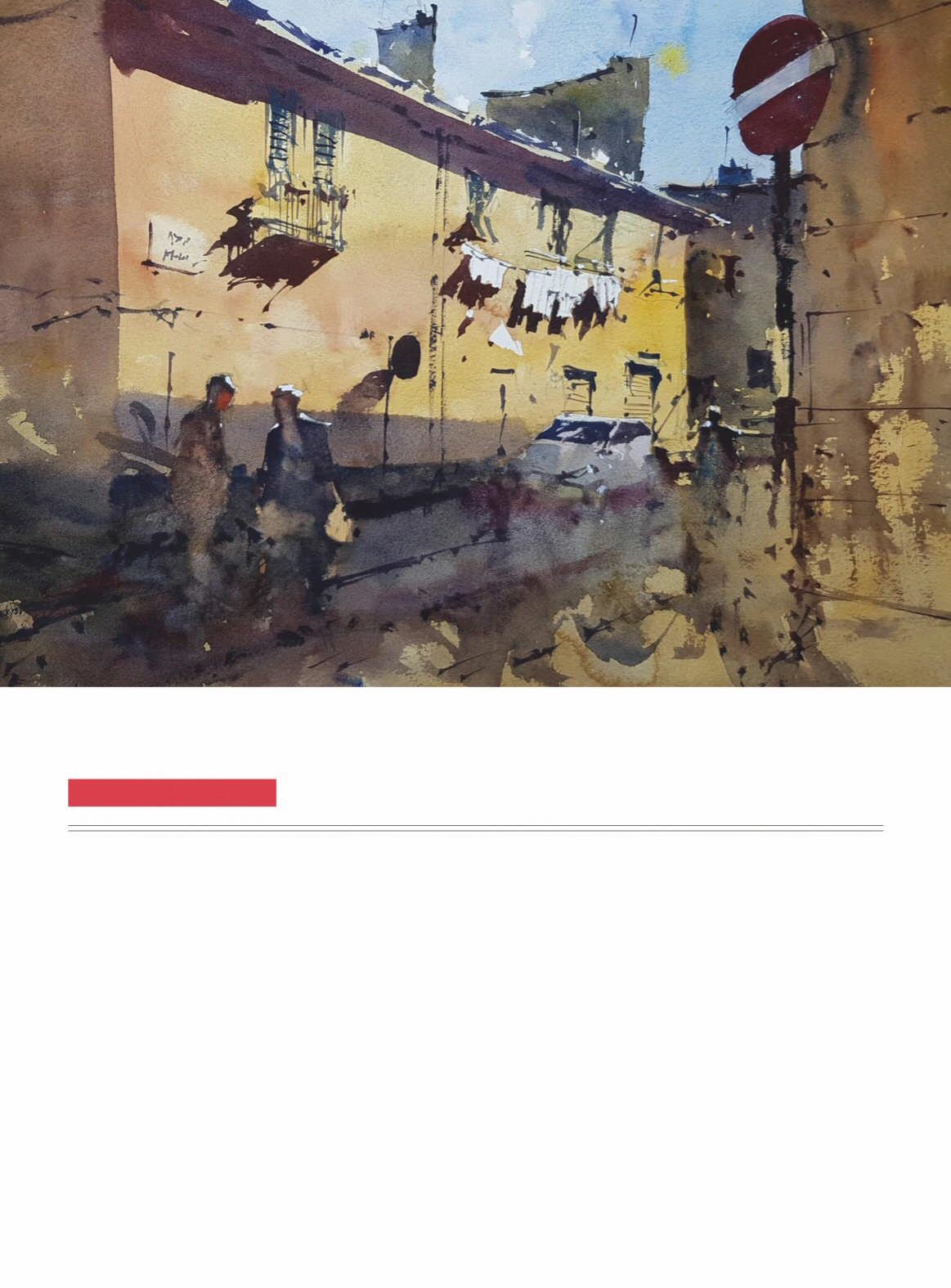

BACK ROAD GETAWAYS

ITALY IS REVERED for its countryside and its cityscapes, but one of those prospects calls to artist Tim Wilmot (timwilmot.com) more: “Th e countryside. Defi nitely,” says Wilmot. “Although a lot of my paintings are street scenes slightly off the beaten track, it’s getting away from the city centers along ordinary streets that I’m attracted to—authentic, ordinary backstreets, little coastal scenes, harbors. Th ere’s a real charm to them.” His preference for these off -the-beaten-path places dates back to his fi rst experience in Italy some 35 years ago during a summer conference in Sorrento, near Naples. He took time to roam the less popular areas of the city, exploring on his own.

As a plein air painter, Wilmot describes the opportunity to work outside in Italy as “a brilliant experience—the ultimate for painting.” He explains, “I love being outdoors and I love painting. Italy off ers a great combination of the two. Th e climate defi nitely helps. Living in the U.K., we often think of places like Italy as nice to go to in the summer for a little bit of sun and a diff erent climate.”

Washing Line,

Livorno (watercolor on paper, 103⁄5x15

Whether painting outdoors or in the studio, Wilmot sticks to the same palette of warm colors for his Italy-based body of work, often featuring reds against cool blue skies, strong sunlight and cypress or palm trees. “Th e ochres are very important,” he says. “I don’t have a wide palette. I stick to nine or 10 main colors: burnt sienna, yellow ochre, cobalt green, cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, alizarin crimson, a light red, a bright red, cadmium orange, cadmium yellow—a combination of those is everything I need.”

During his visits to Italy, made roughly once a year, Wilmot has found a living culture of support for artists, as opposed to solely historic interests. “Painting is highly regarded in Italy, a creative pastime worth following. I’ve recently given workshops online with attendees from Italy numbering as many as 60 to 70 people.”

When asked what impact Italian art history has on his own work, Wilmot replies emphatically, “None whatsoever. I live for the now.” As a result, the artist doesn’t put Italy on a pedestal. Paintings such as Washing Line (above),

TOP TO BOTTOM

Livorno Canal Corner

(watercolor on paper, 103⁄5x15)

Fivizzano No. 1

(watercolor on paper, 103⁄5x15)

Livorno Canal Corner (left) and Fivizzano No. 1 (below) show unglamorous street scenes and humble dwellings, anonymous corners of everyday places. Nevertheless, the main characters of Wilmot’s Italian works aren’t the street signs, lamp posts and clotheslines he often depicts. “It’s the shadows.” says Willmot. “Ordinary objects casting interesting shadows across buildings.”

He goes on to explain, “Th e attraction to me is fi nding something that’s ordinary and trying to make a statement about it, to fi nd something artistic about it. Defi nitely, the ordinary is my key thing, but the scenes are romantic to me—I love them all.” WA

Courtney Jordan is a freelance fi ne arts writer who makes her home in New York City.