Milton Resnick Hawkeye

with an essay by Klaus Ottmann

van doren waxter New York: 2022

stand fast; to stand or fall Free in thine own arbitrement it lies. —John Milton, Paradise Lost

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure And so each venture Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate . . . —T.S. Eliot, “East Coker”

MILTON RESNICK (1917–2004) has long been associated with Abstract Expressionism; yet, as the painter and writer Geoffrey Dorfman has elegantly stated, “his artistic makeup did not provide for a comfortable fit.”1 Resnick always seemed to be, mostly of his own accord, the odd artist out. During his long artistic presence in New York City, interrupted only by a five-year stint in the U.S. Army (from 1940 to 1945) and two years studying and painting in Paris (from 1946 to 1948), his work straddled both figuration and abstrac tion. His early figurative paintings from the 1930s were informed by his training as a commercial artist at the Hebrew Technical Institute, which he attended instead of high school, and at the real ist-aligned American Artists School. It was the work that followed, his gestural and colorful abstractions of the 1950s and early 1960s, that earned him the title of being “the last Abstract Expressionist painter” by critic Roberta Smith (in her 2004 New York Times obit uary of Resnick). In the 1970s and 1980s he mostly abandoned the established canon of Abstract Expressionism to create large abstract canvases with a reduced color palette, until he returned to expres sionist figuration toward the end of his life—yet always challenging

1. Out of the Picture: Milton Resnick and the New York School, transcribed, compiled, and edited by Geoffrey Dorfman (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2002), 1. All quotes by Resnick, unless otherwise noted, are taken from this book.

the capacity of painting to be representational. What has remained consistent throughout was his unrelenting belief in the evocative power of paint.

Resnick has been compared to Willem de Kooning, Claude Monet, and Philip Guston, yet none of these artists matched his single-minded pursuit of the unfathomable abyss that Modernism revealed in the late nineteenth century. One who did was the French painter Chaim Soutine, whose work Resnick encountered during his time in Paris and whose “lack of an edge” was an early inspiration for Resnick.

Like Soutine, who used forceful brushwork and heavy impasto to create haunting still lifes of beef carcasses and dead birds—which the critic Peter Schjeldahl compared to “something between a mud-wrestling match and a fight to the death”2 —Resnick’s darker and more densely layered canvases of the 1970s and 1980s convey a sense of loss.

Philosophers, poets, and artists seek to understand life at its deepest level. Ultimately, as the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once said, they always run up against the boundary of language. One might call this boundary “the nonrepresentable,” “the indefinite,” or “the Absolute.” Thus the question of art is, as Tolstoy remarked in his 1896 pamphlet What Is Art, forever linked to “the conditions of human life”3 and is ultimately a question of life and death. “Paint ing at its most intense revels in its deathliness,” wrote the art historian T.J. Clarke in his study on Poussin.4

Resnick often spoke in religious terms, but unlike one of his early mentors, the painter Max Schnitzler, who came from an Orthodox Jewish background, Resnick was not an observant Jew and never “placed the Torah on the easel.”5 Both he and his wife, the painter Pat Passlof, worked in deconsecrated synagogues that they converted into studios, and Resnick has described painting as “breathing

2. Peter Schjeldahl, “The Vulnerable Ferocity of Chaim Soutine,” The New Yorker, May 7, 2018.

3. Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art, translated by Aylmer Maude (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1904), 47.

4. T. J. Clark, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 236.

5. Resnick, in conversation with Geoffrey Dorfman, in Out of the Picture, 27.

something onto the canvas,”6 recalling the spirit or breath described by the Hebrew word Ruach in the first book of Genesis. Other Old Testament references can be found in paintings such as Fire B (1975) or the much earlier Burning Bush (1959), which, as the writer Nathan Kernan has stated, “suggests a metaphor for painting itself: as some thing alive and actively ‘burning’ but never consumed.”7 Both paintings may also allude to “that [creative] fire, that burning” that Schnitzler told Resnick he saw in Arshile Gorky.8

In the early 1970s Resnick began two remarkable series of paint ings titled explicitly after animals (hawks and elephants). The “Hawkeye” series of works on paper, delicately layered like a “thing with feathers / That perches in the soul,”9 are smaller in scale but no less evocative than the second, later series of “Elephants,” which range from 81 to 209 inches in width and are much darker, with sur faces built up with thick impasto paint until they resemble an ele phant’s hide, or appear fortified like a protective armor. Comparing painting to swimming in the ocean, Resnick once told his students:

Very quickly you began to put on armor. You become very conscious that without this armor you cannot get to shore again.

It has something to do with life.

The “Elephant” paintings, covered with blotchy dark gray paint, lit erally became the “Elephant[s] in the Room” (as a 2011 exhibition of his paintings was cleverly titled) when the first six paintings from the series were originally shown at the Max Hutchinson Gallery in New York in April 1979.

6. Resnick, New York Studio Talk, 1972, in Out of the Picture, 204.

7. Nathan Kernan, in Milton Resnick: A Question of Seeing—Paintings 1959–1963 (New York: Cheim & Read, 2008), exh. cat.

8. Quoted in Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, De Kooning: An American Master (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 99.

9. Emily Dickinson, “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” in Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries, edited by Helen Vendler (Cambridge, Mass. and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010), 118. Vendler explains Dickinson’s use of the word “thing” as “her single largest mental category, which can embrace named and unnamed acts, creatures, concepts . . . It is as though she begins each inquiry with the general question, ‘What sort of thing is this?’ and then goes on to categorize it more minutely: major thing or a minor thing, a present thing or an absent thing, a live thing or a dead thing.”

Most likely written by Resnick himself, the press release for the 1979 show stated:

This is an elephant show

Some of these new paintings are elephants and some are not. [Res nick] is always taking something out because he sees something else behind it. Thinking there’s a lot more that hasn’t been seen yet, he’s always removing what he doesn’t want to see. Color, form, light and dark, harmony and images (like little people, mountains, noses, etc.) to Resnick are just dead horses.

And yet he doesn’t act accordingly. He puts a lot of paint on when what he wants is to uncover, but only by using a lot of paint can he understand its nature and what it can do.

The point is, it is hard to paint with no dead horses to beat. Resnick cares only for paint.

On painting dead elephants instead (or elephants that play dead, as Phillip Larrat-Smith suggested10), Resnick has said:

Is it possible that the thing that has been spoken of as the creative nature of the artist is really some kind of death machine? . . . It could be the death that you can suffer over and over again.

And referencing his “Elephants” series directly, and in relation to a series of vertical paintings, which he made concurrently and called “Straws” or “Straws in the Wind,” he remarked:

It is not YOU that is important in painting, it is what the painting is telling you. You must make the painting stronger than you. So when the painting is the elephant or the wind—and you are the straw—then you know how to paint.

The archetypal psychologist James Hillman, who has thought deeply about how animals are interiorized into the human soul, wrote:

Again and again, the elephant is associated with the majesty of kings and gods . the elephant is a bringer of weight and bearer

10. “Play Dead,” in Milton Resnick: The Elephant in the Room (New York: Cheim & Read, 2011), ex. cat.

of weight, whether in the world or in word; the strength and endurance of substantial virtues.11

In Poussin’s famous painting Hannibal Crossing the Alps on an Ele phant, it is the elephant (rather than the military strategist and hero of the Second Punic War riding it) that becomes the symbol for the greatest fighting force ever assembled in ancient times (consist ing of more than 40,000 soldiers and 37 elephants).

Like the elephant, hawks are a symbol of power, in addition to being “all-seeing” due to their powerful eyesight, which is five times sharper than that of humans. In Hesiod’s Works and Days, a hawk is quoted saying, in effect, “I have the power to devour you” (lines 202–212). Likewise, Resnick’s paintings of the 1970s have the power to devour: light, color, one’s self, and the world. As Resnick told the critic, painter, and art instructor Lawrence Campbell, who wrote about the artist in 1957 for Artnews’s groundbreaking series of arti cles that followed the creation of a work of art from the beginning to its completion:

What I like is a painting to act in many different directions at once, so strongly that it will shatter itself and open up a small crack, which will suck the world in.12

A highly verbal artist (“I love to talk. The World is too large not to talk”), Resnick engaged in many conversations with Geoffrey Dorf man and with students at the New York Studio School that took place between 1968 and 1972 and were transcribed by Dorfman. They reveal much about his process of painting, which he viewed as a progression of failures: “When it comes to something as form less as art is, you can’t help but fail.”

He once asked his students: “How do you get to work on a canvas without knowing anything?”:

You are . . . about to attack this blank canvas—and the first thing you find out is that you’re falling. You get this strange feeling that when you reach, you fall; what has seemed very solid to

11. “The Elephant in the Garden of Eden,” in James Hillman, Animal Presences (Thompson, Conn.: Spring Publications, 2022), 132–36.

12. Lawrence Campbell, “Resnick Paints a Picture,” Artnews 56, no. 8 (December 1957): 39.

you is no longer solid. If this paint which came out of a tube is now on your canvas, and at the very same moment you say “art” to yourself, you fall. . . . Whether you know it or not, you’re falling. How do you fall without completing this fall? How do you avoid falling on your face? How do you fall without falling completely?

Resnick painted from within a continuous act of falling—a terrifying and exasperating process for the artist that brings to mind John Milton’s lines from Paradise Lost (10.288): “tossed up and down together shoaling towards the mouth of hell.” As Campbell can attest, this act of falling experienced by an artist in their studio is often re-experienced by the viewer. Campbell recalls:

I was interested in watching Resnick paint. But I did not learn much from it about his ideas. A Resnick painting has a hundred stages. Hardly anything remains from one visit to another. Nine-tenths of the paint ended up in scrapings on the floor. Even so the paintings were unusually heavy.13

The experience of falling from a state of knowing into a state of not-knowing or emotion is what for Resnick constituted the begin ning of the creative process. It is the reversal of the biblical fall unto knowledge; yet it is only a temporary suspension of the human con dition, which began after the fall and is defined by our mortality. Again, Resnick speaking to his students:

Falling is dying. At least it is the knowledge that you will, in some way or other, receive the blow that will be your undoing

The artist who is falling yet prevents himself from falling has, by this time, in his state of grace, realized that timelessness has something to do with death.

And it’s only then that the thing becomes very serious. It runs away from the intellectual to the emotional. . . .

The one thing that the emotional bath that you are now indulging in, standing in front of your canvas—feeling and not thinking—is that it does something to those poles. Those ideas of good and evil—night and day, begin to lessen within you.

13. Ibid.

The artist’s act of creation originates in a decision to make visible the conflict between the pressing of the unfathomable or non-representable to be represented and its inability to be represented.14 It is a decision that in Resnick’s case results in a representation of fall ing towards beauty through failure

In an animated exchange with one of his students about the experience of pain and failure, Resnick brings up the notion of beauty:

There is another word that I have sympathy with and the word does come up—beauty. What does that mean? Again, I find myself in circles but I do think about it… Seeking an answer is not the thing to do.

But when you say “beauty”—

Well, that’s not an answer exactly. I can still sympathize with the word. If there is a difference between the kitchen and the temple, say—I would prefer the temple… I have sympathy with something better than a f*cking kitchen.

Looking at Resnick’s paintings it becomes almost instantly clear why Resnick chose the temple over the kitchen; the extraordinary over the ordinary; poetic beauty over prosaic pursuits: “Every day poetry day.”15

klaus ottmann is an independent curator and writer, and chief curator emeritus of The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. He is also the publisher and editor of Spring Publications. In 2016 Dr. Ottmann was conferred the insignia of chevalier of France’s Order of Arts and Letters by the French ministry of culture and communication.

At the Phillips, he has curated the exhibitions Nordic Impressions: Art from Åland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, 1821–2018; George Condo: The Way I Think; Arlene Shechet: From Here On Now; Karel Appel: A Gesture of Color; Hiroshi Sugimoto: Conceptual

14. I have described this “decision” in greater detail in my The Genius Decision: The Extraordinary and the Postmodern Condition (Thompson, Conn.: Spring Publi cations, 2015).

15. “Every day,” in Up and Down: Poems by Milton Resnick (New York: Pandemo nium [Hauge Passlof], 1961), 48

Forms and Mathematical Models; Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet; and Per Kirkeby: Paintings and Sculpture; and oversaw the installation of a second permanent installation at the Phillips, a Wax Room created by Wolfgang Laib. Dr. Ottmann has curated more than 50 international exhibitions, including Jennifer Bartlett: History of the Universe. Works 1970–2011; Still Points of the Turning World: SITE Santa Fe’s Sixth International Biennial; Life, Love, and Death: The Work of James Lee Byars; Wolfgang Laib: A Retrospective; and Strange Attractors: The Spectacle of Chaos. His publications include Yves Klein by Himself: His Life and Thought; The Genius Decision: The Extraordinary and the Postmodern Condition; and The Essential Mark Rothko. In 2006 he translated and edited Yves Klein’s complete writings, Overcoming the Problematics of Art: The Writings of Yves Klein.

Untitled, 1976, acrylic on paper, 36 x 24 inches (91.4 x 61 cm)

Untitled, 1975, acrylic on paper, 36 x 24 inches (91.4 x 61 cm)

Untitled, 1976, acrylic on paper, 36 x 24 inches (91.4 x 61 cm)

Untitled, 1976, acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Untitled, 1976, acrylic on paper, 36 x 24 inches (91.4 x 61 cm)

Fire B, 1975, oil on canvas, 90.25 x 80 inches (229.2 x 203.2 cm)

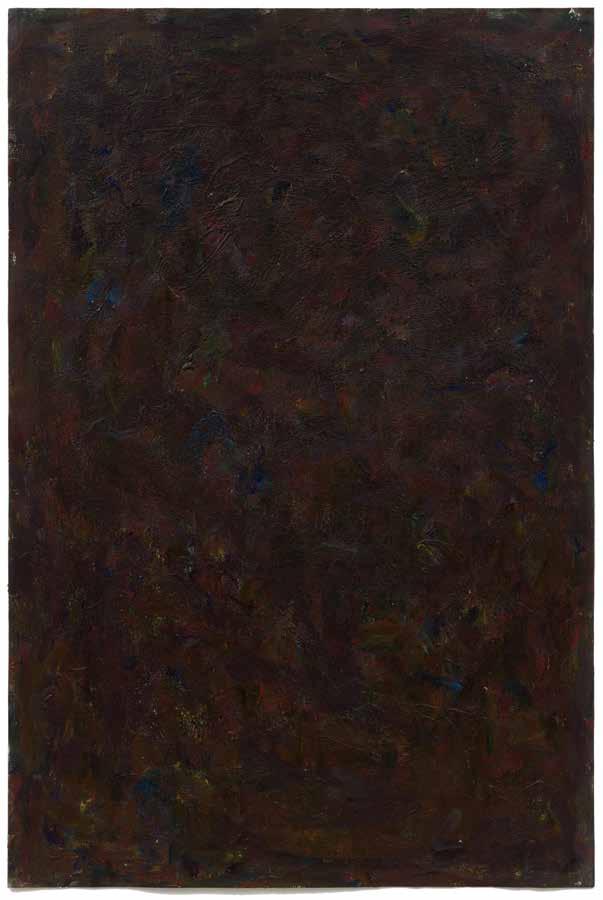

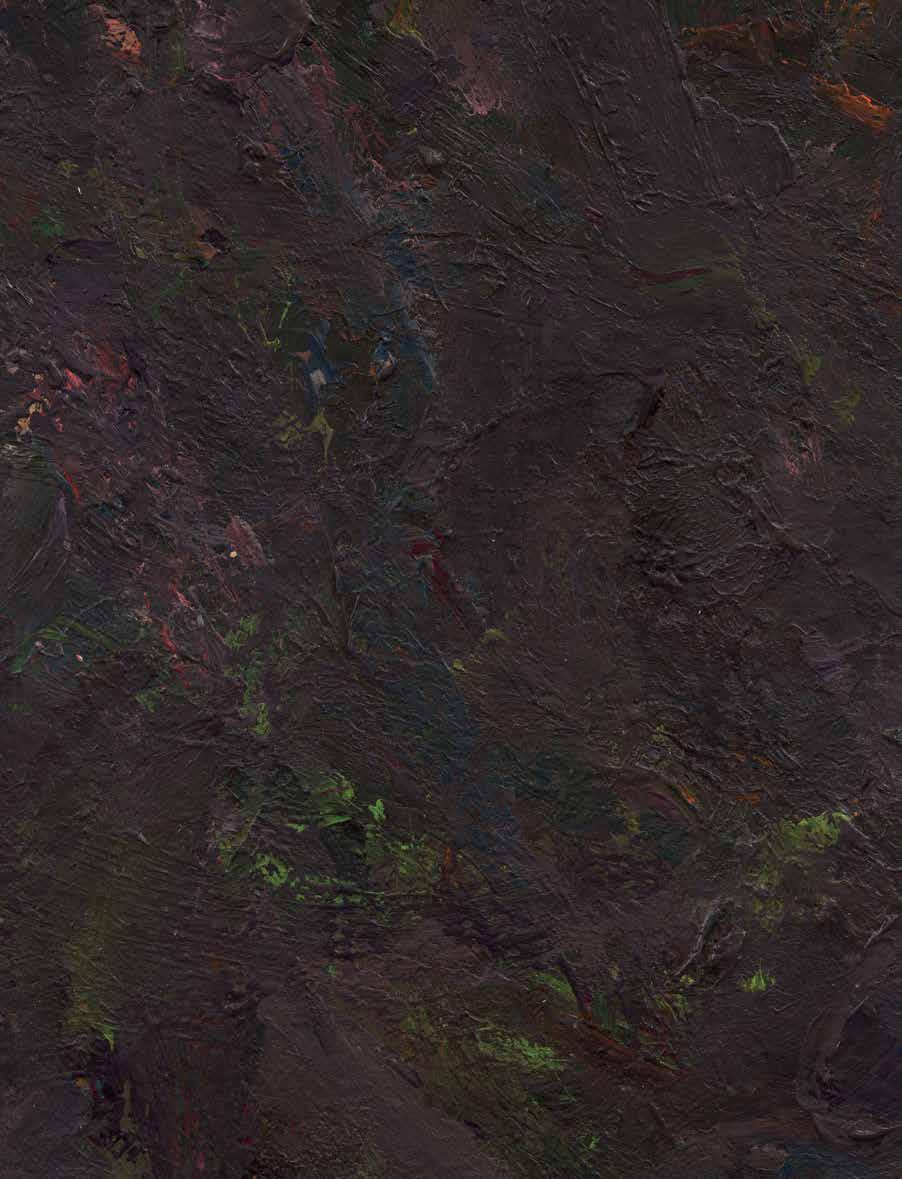

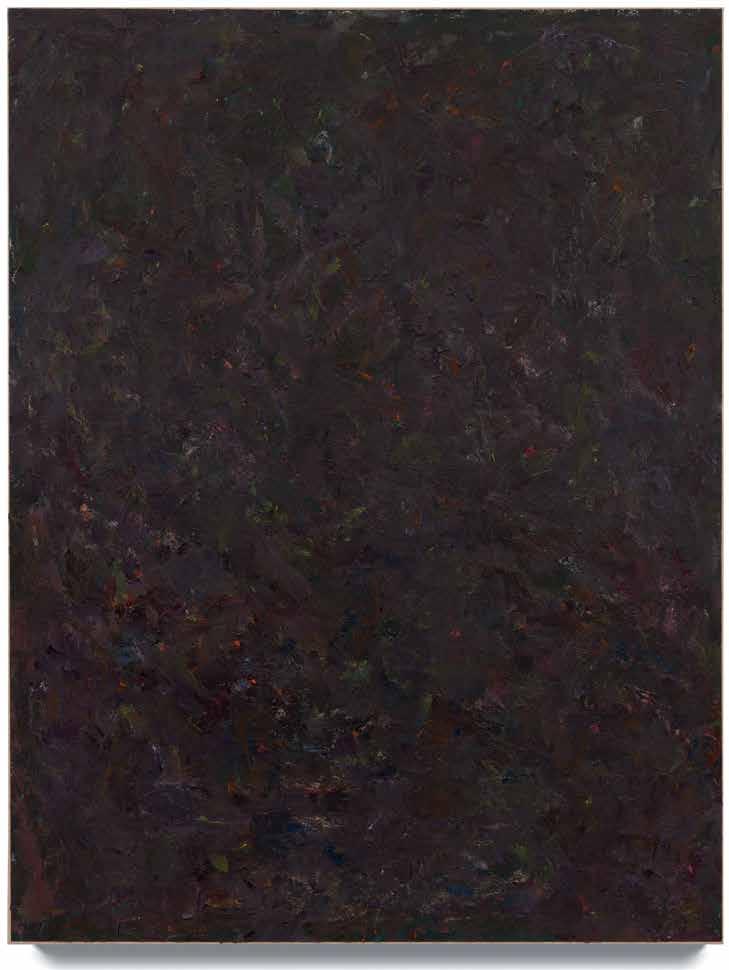

Hawkeye 12, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 12, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

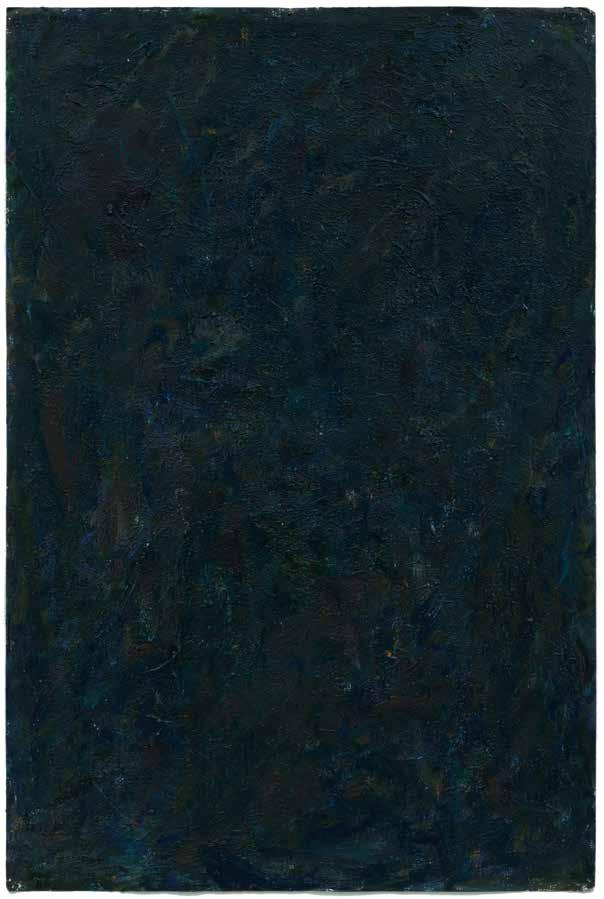

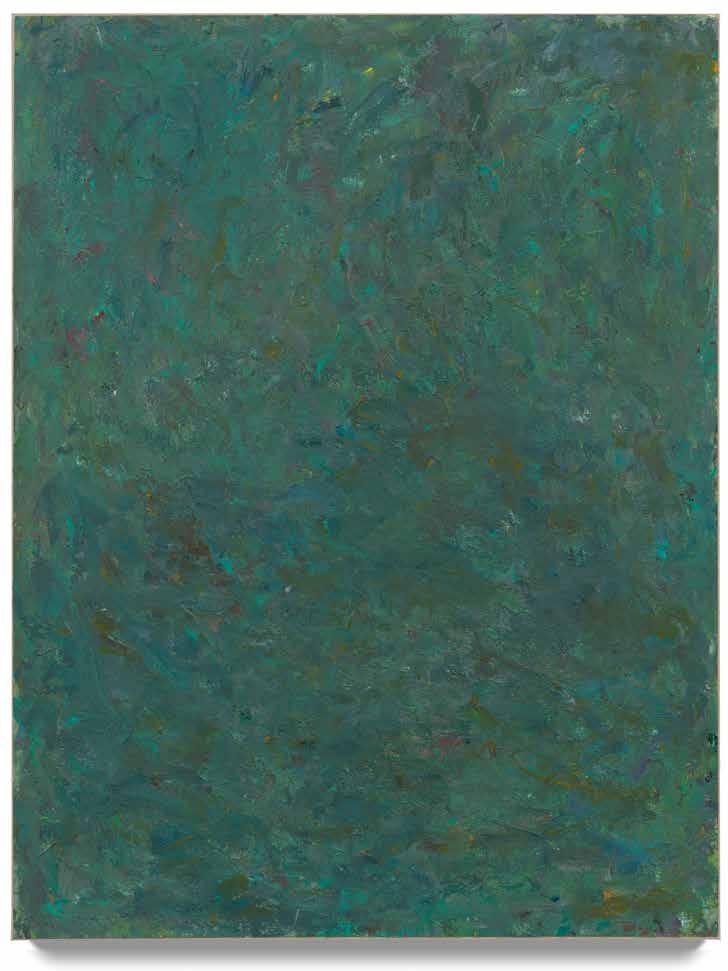

Hawkeye 6, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 6, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

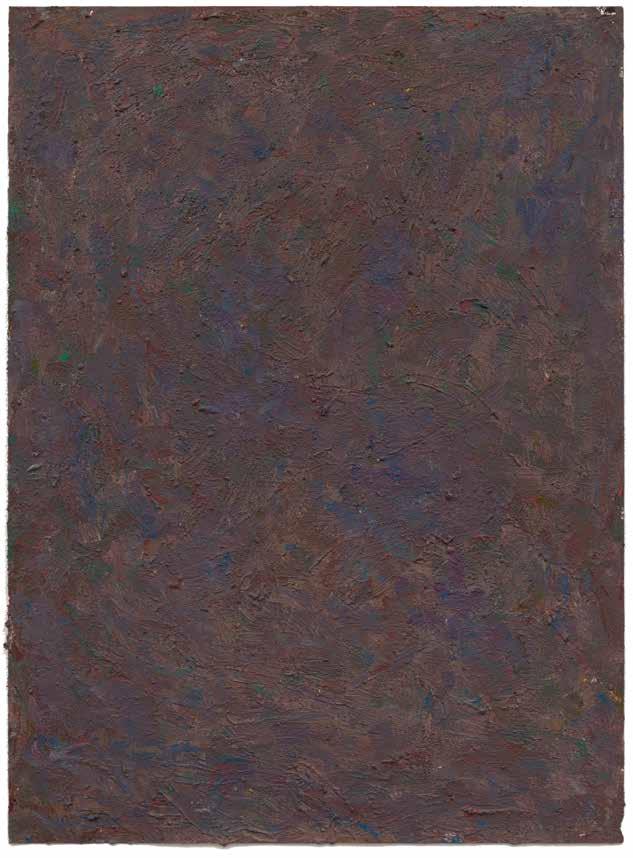

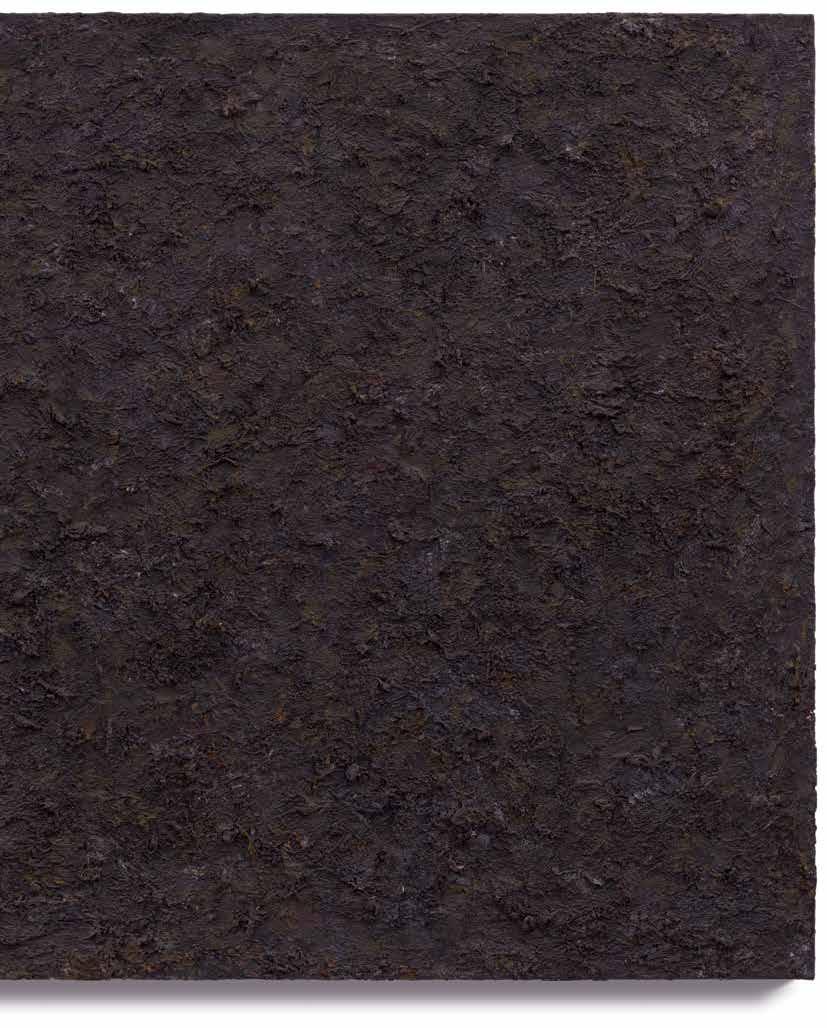

Hawkeye 9, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 9, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

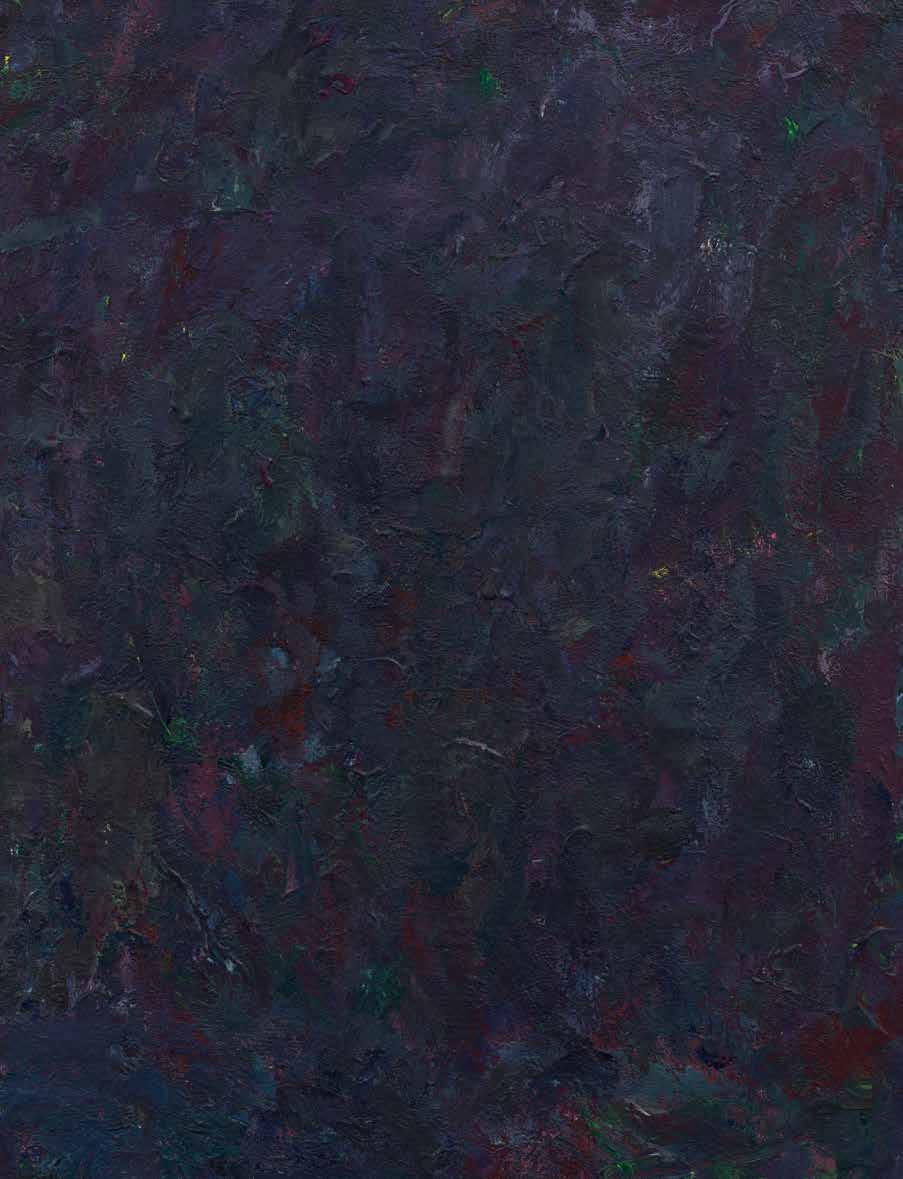

Hawkeye, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 11, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 11, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 10, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 10, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 15, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

Hawkeye 15, 1972, acrylic on paper mounted on linen, 50 x 38 inches (127 x 96.5 cm)

1917 Born Bratslav, Ukraine, January 7

1922 Immigrated to the United States

2004 Died New York, March 12

education

1932 Pratt Institute 1933–37 American Artists School

1938–39 Worked for W.P.A. Art Project

1940–45 Military Service, U.S. Army 1946–48 Lived and painted in Paris

solo exhibitions

2021 Milton Resnick: Paintings 1954–1957, Cheim and Read, New York, New York

2018 Milton Resnick: Paintings 1937–1987, Milton Resnick & Pat Passlof Foundation

Milton Resnick: Apparitions, Reapparitions, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Milton Resnick: Boards 1981–1984, Cheim & Read, New York

2014 Milton Resnick: Paintings and Works on Paper from the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation, Mana Contemporary, New Jersey

2012 Milton Resnick, Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

2011 Milton Resnick: The Elephant in the Room, Cheim & Read, New York

2008 Milton Resnick. A Question of Seeing: Paintings 1958–1963, Cheim & Read, New York

2006 Milton Resnick: The Life of Paint, The Anthony Giordano Gallery, Dowling College, Oakdale, New York

Black & Blue, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

2005 Milton Resnick: Late Works, New York Studio School

2002 Milton Resnick Five Years: 1959–1963, Robert Miller Gallery

2001 Milton Resnick: X Space, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

2000 Nielsen Gallery, Boston

1997 Milton Resnick Monuments, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1996 Recent Paintings, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1995 Recent Paintings, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1992 Robert Miller Gallery, New York

The Substance of Painting: Part I Milton Resnick: New Paintings on Paper & Panel, D. P. Fong and Spratt Galleries, San Jose, California

1991 Milton Resnick: Straws 1981–1982, Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1988 Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles

Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1987 Galerie Montenay-Delsol, Paris

Meredith Long Gallery, Houston, Texas

Compass Rose Gallery, Chicago

1986 Arbeiten auf Papier, Galerie Biedermann, Munich

Robert Miller Gallery, New York

Gallery Urban, Nagoya, Japan

1985 Robert Miller Gallery, New York

Milton Resnick: Paintings 1945–1985, Museum of Contemporary Art, Houston (traveled to University Art Museum, California State University, Long Beach)

Hand in Hand Galleries, New York

Meredith Long Gallery, Houston, Texas

1983 Gruenebaum Gallery, New York

Main Gallery, Art Department, San Jose State University, San Jose, California

1982 Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York

1980 Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York

1979 Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York

Robert Miller Gallery, New York

1977 Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York

1975 Poindexter Gallery, New York

1973 Kent State University Art Galleries, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

1972 Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York

1971 Roswell Museum and Art Center, New Mexico

1969 Arden Anderson Gallery, Edgartown, Massachusetts

1968 Reed College, Portland, Oregon

1967 Madison Art Center, Madison, Wisconsin

1964 Howard Wise Gallery, New York

Feiner Gallery, New York

1963 Zabriskie Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts

1962 Feiner Gallery, New York

1961 Howard Wise Gallery, New York

1960 Howard Wise Gallery, Cleveland, Ohio

Howard Wise Gallery, New York

1959 Ellison Gallery, Fort Worth, Texas Holland-Goldowsky Gallery, Chicago Poindexter Gallery, New York

American Association of University Women of Rochester, New York

1957 Poindexter Gallery, New York

1955 The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, M. H. de Young

Memorial Museum & California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco

public collections

Akron Art Museum, Akron Ohio

Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell, New Mexico

Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, University of Texas at Austin, Texas

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkeley, California

Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Calcutta, India

Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin, Texas

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Carlson Gallery, University of Bridgeport College of Fine Arts, Bridgeport, Connecticut

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

College Union Collection, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Fort Wayne, Indiana

Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York

Hampton University Museum, Hampton University, Hampton, Virginia

Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawaii

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Jonson Gallery, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Madison Art Center, Madison, Wisconsin

Malmö Konsthall, Malmö, Sweden

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, North Carolina

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas

Museum of Modern Art, New York

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey

Roswell Museum and Art Center, Roswell, New Mexico

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, California

Sheldon Museum of Art and Sculpture Garden, University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Nebraska

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Tufts University Art Gallery, Somerville, Massachusetts

University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, Iowa

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, North Carolina

Wexner Center for the Arts, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

November 3–December 23, 2022

Designed and produced by Ink, Inc., New York

Edited by Dorsey Waxter, Nick Naber, and Peter Kelly

Artwork photography by Lance Brewer

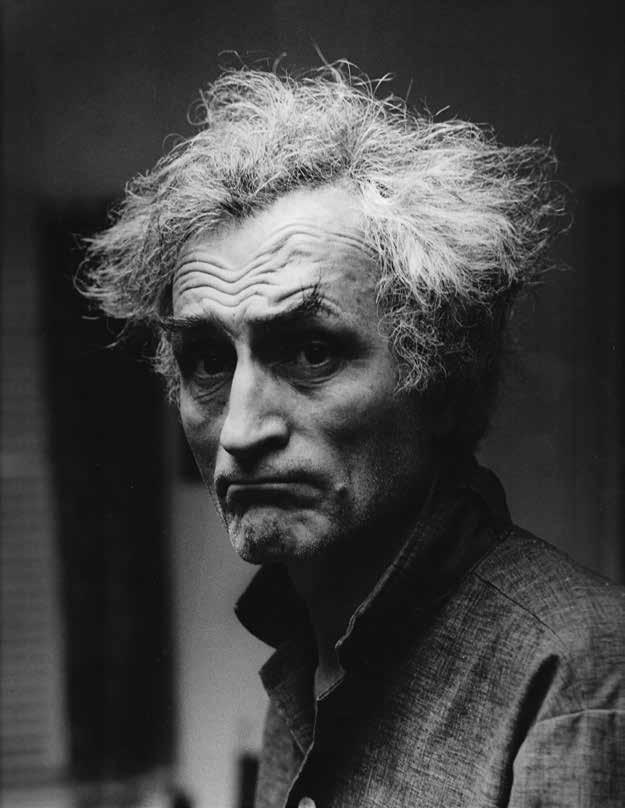

Page 34: photo by Leon Walters, n.p., c. 1971

All works © the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation

It is with great pleasure that we present the current exhibition of paintings and works on paper by Milton Resnick (1917–2004). This show would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation most especially Susan Reynolds, Nathan Kernan, Geoffrey Dorfman and Alex Chapin. Special thanks go to Klaus Ottmann, independent curator and writer for his essential insights into the artist and his works.

VAN DOREN WAXTER

23 East 73 Street New York, New York 10021

Phone 212 445-0444

info@vandorenwaxter.com www.vandorenwaxter.com

ISBN: 978-17325933-8-1

Copyright © 2022 VAN DOREN WAXTER, New York, New York

Essay copyright © 2022 Klaus Ottmann

All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this catalogue may be reproduced without permission of the publisher.

van doren waxter