LETTER FROM EDITOR

I am very excited to present you with the 16th edition of Contrast. This semester we sought to center unique and untold Vassar stories. To that end, we had the privilege of interviewing Raegun, a rising star in the Digicore tech music scene, who became our cover story. Elsewhere, we explored how undergarments, by shaping the form itself, shape our perceptions of ourselves and each other. Finally, we highlight a story about how clothing and material culture can mean much more than what is obvious.

I hope you enjoy. Much love!

Faking Figures

by Anjali Krishna

by Anjali Krishna

A couple years ago I was watching a Bernadette Banner video on corsetry, and she said something I’ve never been able to shake from my mind. If you’re a fashion history nerd like me, you know Bernadette. She’s that slightly unhinged person on Youtube that does ridiculous things like making mini series on how to sew an European 19th century ball gown, but refuses to use current technology, instead insisting on hand sewing and finishing the entire dress by hand (please go watch it, she’s so good). But aside from these extended, soothing, ASMR-like tutorials that I watch religiously but will never follow, Banner proves to be a walking encyclopedia of Victorian fashion knowledge. So when she put forth the idea that achieving the “ideal” body shape may have been easier in corsets than it was today, I sat up and listened.

Banner paraphrases Luca Costiligono from Patterns of Fashion 5 (a seminal book series for historical reconstructionists) who states that there is “no such thing” as the “modern” body in comparison to the Victorian body, claiming that the basic ratios and proportions of a human body today are relatively the same as your everyday Victorians. Instead the silhouettes of each time period –– wasp waist, pigeon breasted, bustled rump –– were achieved with “copious

amounts” of padding and the creation of optical illusions.

In one video, Banner calls in a plus size historical dresser, who explains why this is so significant to recognize.

“In today’s society we have shame with making yourself larger in any way, in any part of your body. Like, today’s society wants you to make every single thing you have smaller…Historically they didn’t have any problem with making themselves larger in certain areas…just make your hips and shoulders wider, and instantly your waist looks smaller.”

Banner follows her up by talking about historical pattern drafting books, in which a single pattern might be reprinted 6 times for 6 different body types: “stooped,” “stout,” “erect” etc. She describes padding out her own figure to make her spine, bent from scoliosis, seem more symmetrical and prevent uncomfortable pressure. Overall, the impression that I got, and that I haven’t been able to let go of, was that the Victorians had more options available to them when it came to achieving the fashionable silhouette, which blew my mind and also made me a little jealous. My clothing options don’t really allow me to create illusions. I feel like I’m missing out on a level of control over my own self-expression, and isn’t that what fashion is all about?

So what has changed? Why do we now have a taste for thinness everywhere? The more I thought about it, the more I narrowed in on one factor that the 21st century fashion just hasn’t taken advantage of: underwear.

This semester I took part in an intensive course cross listed under nineteenth century studies and drama called “Searching for the Makers.”

We were given access to garments in the Vassar Historical Costume Collection (an incredible resource that I didn’t even know existed until last year) and researched their time period, garment history, wearers and most importantly, tried to figure out who made them. One of the things that we quickly learned was the importance of silhouette as a marker of time period.

1850 - 1869 was the crinoline period, and dresses were bell shaped. The Edwardian era was from 1900 - 1910, and the body took on an S curve, with chests thrust forward and hips pushed back. However, just as quickly we learned that it was underwear, and not bodies, that built these silhouettes. The dress I worked on had a small waist and huge, bell shaped skirts, typical of the 1850’s. Another was smooth fronted but had a large bustle in the back, decorated with extensive trimmings, gathers and a bow, characteristic of the 5

1870’s. Neither of these dresses could achieve their trademark silhouettes without the corresponding underwear. The first dress had both hoop skirt and petticoat, and was definitely worn with a corset, considering that the waist measurement was 21 inches. The voluminous skirts and sloping, dropped shoulders made the already small waist look even tinier. The 1870’s gown had a hoop as well, but this one was designed to protrude off the

rear, supporting just the bustle. Both hoops were extremely lightweight and flexible, and although scary looking to the modern eye, actually would have put less of a burden on the wearer than layers upon layers of heavy skirt fabric.

Underwear was everything to the Victorian dresser. Corsets, petticoats, bustle cages, and bust pads, were all carefully layered and sheathed under

the outer dress. It was inconceivable that the fashionable silhouette could be achieved without them. Whatever your natural body shape was, it could be manipulated with underwear. In this manipulation there was freedom: freedom to control how the world viewed you, freedom to construct the image you desired. As Banner explains, the Victorian expectation was that every body was different, and that clothing had to be adjusted accordingly to fit each unique person. Today, fashion labors under the opposite school of thought: that we must adjust ourselves to fit in clothes. Along with this comes an obsession with having not only the “perfect” body, but the perfect “natural” body. In the Victorian era, undergarments were publicly advertised and widely available. Corsets were sold for sports, for sleeping, for maternity and more. As such, I doubt there was much pretense about the “naturalness” of a woman’s figure. No one would have been shocked to undress a lady and find that she was wearing bust or hip padding –– it was par for the course. Sadly, we don’t have nearly that amount of nonchalance today –– people lose their shit when the background of an instagram photo is slightly warped. While there have been social media movements that push influencers to acknowledge photoshopping, and plenty of articles attempting to reveal the Kardashians’

plastic surgeries, we are still sold the narrative that with enough hard work and dieting, we can achieve the desired figure.

It’s just not true. Despite our undergarments getting smaller and smaller, and more of our bodies becoming exposed, our body standards remain just as ridiculous as in the Victorian era. The difference being that now we project an impossible image onto flesh instead of fabric. So, we get plastic surgery, drink teas that make us sick, and fast before big events, all the while attempting to seem like we aren’t doing anything at all –– we’re just born this way.

A solution to this pain has emerged in the body positivity movement, which preaches the truth: that all bodies are worthy of love, that all bodies deserve to be admired and that shame has no place in fashion. Yet, despite the movement gaining traction, there is no doubt that fashion continues to exclude people of different body shapes and types. As much as we claim that anyone can wear anything, most clothes, especially in high fashion, aren’t designed with universality in mind. Jeans dig into waists that are “too big,” thighs chafe in shorts that ride up, and blouses gap because chests are “too small.” People of different shapes and sizes shouldn’t have to force themselves into discomfort for the

sake of fashion; garments should be designed for us, not the other way around.

Well damn, what a depressing state of the world. So what does the future hold? To be honest, I don’t know. While it’s lovely to see the resurgence of Victorian undergarments worn on top of clothes as statement pieces, and more and more people are unlearning myths associated with corsetry (Keira Knightly/Elizabeth Swann fainting off of a cliff because of the tightness of her corset delayed us, like, 20 years), they won’t be returning to regular use as an undergarment anytime soon. And hoop skirts? Forget about it. But what I am most excited about is the explosion of “non-natural” silhouettes we’ve seen in recent years. The voluminous Selkie puff dress, the molded golden abs of a Schaparelli gown, the exaggerated, alien sculptures of Balmain and Iris Van Herpen. These forms have no pretenses, they fully embrace being illusionary and artificial. Their abstraction makes them feel like they could be worn by anyone wanting to control the shape they carve out in the world, and that is thrilling. When all is said and done, I hope we continue down this path of faking it, because everyone is, and as the Victorians show us, we always have.

Fashion Collaborations: How far is too far?

by Wyatt KeleshianGucci. Adidas. Balenciaga. The unholy trinity of the religion that is luxury fashion. Everytime I open any sort of social media, it seems these brands have consumed the timelines. Just when I thought it was getting out of hand with the individual brands, they started collaborating with each other. Lord help us all.

Designer collaborations seem to be the hottest headline in the fashion industry, even if they’re between brands that have no association to each other. It begs me to ask the question: who asked for this? Do consumers truly want their corneas assaulted with $3,000 leather bags embossed with an Adidas logo, or Gucci scarves plastered in BALENCIAGA? These current luxury collaborations appear to be more about what will get the fashion world talking and less about creating pieces that promote aesthetic exploration.

The catalyst of these hype-based collections was the Gucci Aria collaboration with Balenciaga. In the “Hacker Project”, Creative Director Alessandro Michele mixed the heritage GG monogram with violent jewels, layered coats, neon velvets, leather harnesses, and ridinging caps (referencing Gucci’s roots in equestrian wear) exemplifying the distinct Gucci maximalist

Gucci x Balenciaga SS22

Gucci x Balenciaga SS22

aesthetic he has worked hard to develop. Unfortunately, Balenciaga logos are garishly plastered on Gucci handbags and screen printed across coats and jackets. These pieces show no blend of artistic style or aesthetics, but rather are a logomania explosion of loud marketing. I can’t help but feel that the collection was a money grab, as any design student can plaster BALENCIAGA on a Gucci Jackie bag or cover a Balenciaga hourglass bag in the Gucci monogram. I think my main problem with this collection is that it relies too much on logos to push its “collaboration” aesthetic

and doesn’t actually show a blend of styles to create a new, unique look.

It would be presumptuous of me to say that all the “Hacker Project’s” collaboration pieces lack artistic merit. Michele references Demna’s Balenciaga by incorporating structural elements like cinched blouses, flowing gowns gathered at the waist, strong tailoring, and utilitarian inspired coats. Yet many of these references are again plastered with the Gucci or Balenciaga logo. But why? If the designers are capable of creating holistically blended collections, why do they then bury them

under logos? My conclusion is this: buyers who are not well versed in fashion history might not recognize that the body-hugging purple top from look 10 i is a direct reference to a look from Demna’s 2017 collection for Balenciaga. Instead, to cater to the everyday consumer, the collaboration had to be more black and white by putting Balenciaga logos on Gucci motifs and vice versa.

Apparently this collection was so successful that it sparked a flood of designer collaborations this year, including two separate Adidas collaborations. There is Adidas x Gucci, which launched in June. And then there is Adidas x Balenciaga (sigh) which launched a couple weeks ago. Both suffer from the same problem: they are boring. And way too similar. They feature the Adidas triple line motif nauseating replicated on leather handbags, tracksuits, and sweaters. There is a t-shirt that has the Adidas logo but says Balenciaga. There is a t-shirt that has the Adidas logo but says Gucci. There is just an obvious lack of design integrity. Balenciaga and Gucci are respectively headed by two of the greatest fashion designers of our time, yet both of these collections look as if they were photoshopped together.

It’s not just the use of logos that makes the collaborations feel lackluster. It’s the lack of anything else. The silhouettes are basic. Oversized Adidas tracksuits selling for thousands of dollars. This is not something original or exciting. The streetwear aesthetic that Balenciaga is still trying to push feels tired and overdone –– hypebeast

silhouettes of oversized shirts and track pants are played out, yet with the Adidas x Balenciaga collection, this proto-streetwear style is all the eye can see. One style that I find particularly odd is a soccer jersey selling for $995. Not only is the vermillion red of the jersey hard to look at, but the jersey itself is poorly fitted as its exaggerated proportions makes it look as though the model is drowning in a pool of red –– exemplifying the collabs overall silhouette and tailoring issues.

Again I ask the question: what is the point?

Selling Adidas track pants that say Balenciaga does not push the boundaries of fashion. It feels as though designers are less worried about creating collections that evoke meaning and unique aesthetics and more focused on designing clothes that will get the most “hype.” These collections practically beg to be displayed on social media. To me, they are not representative of what high fashion truly is and are a result of the rapacity of the fashion industry.

That’s not to say that all collections are poorly executed; I do find some well done. Take the Marni x Uniqlo collaboration from this summer. Bold colors and oversized pants were juxtaposed with florals and stripes. Marni’s maximalist essence translated well on Uniqlo basics. I myself own many Uniqlo tees (they are well made and fit perfectly) and now I could get one designed by a premium design house with a fun pattern without breaking the bank. This collection combines the aesthetics of Marni with the utilitarian minimalism of Uniqlo to create a collaboration that isn’t just for hype amongst the social elite, but increases accessibility by allowing people who might not be able to afford $500 Marni pants to get a taste of the brand’s fashion philosophy for less.

True collaborations should be a blend of aesthetics and designs that complement both parties involved. They should be a celebration of collaborative artistic expression. The sad thing is that these collections could have been done well. Both Demna and Michele have the design skill to create masterful garments and accessories. I’ve seen them do it. To me, these collections show that designers are continuously sacrificing quality collections to money grabs and the pressure of the industry. My hope for the future of fashion is that designers don’t have to make this sacrifice to create hype. Thus, this leaves me with one last, incredibly thought-provoking, word: BALENCIAGA.

Marni x Uniqlo SS22

Nostalgia and Trend Cycles: The Issue With Indie Sleaze

No, I don’t have a personal vendetta against Tumblr.

American Apparel. Ironic t-shirts. Smeared eye makeup. Alexa Chung (it-girl) and Alex Turner of the Arctic Monkeys embarking on one of the most public relationships of the time. Sky Ferreira, Cory Kennedy, Chloe Sevigny, and Alice Dellal reigning over Tumblr. Who are these people? you may wonder. Why is she talking about that one store from a 5SOS song? Well, reader, get ready to learn about indie sleaze. “Indie sleaze” describes the aesthetic of the mid2000s to early 2010s, encompassing both looks and lifestyle. Born out of 80s extravagance and 90s grunge, indie sleaze is gritty nightclubs, flash photography, and overt self-indulgence. Many a “YOLO” and “live in the moment” were flung about. The goal of indie sleaze is to dress the part to be the part, and as such, the indie sleaze lifestyle is characterized by its fashion. It relies on a sense of irony and a rejection of “cringe” to create a shared identity defined by quirkiness. High-waisted shorts were paired with tights to create the perfect FW/SS satire blend. Slogan tees were worn with pride, specifically, those designed by House of Holland. The more “underground” the better.

We have TikTok to thank for the term “indie sleaze” – just “hipster” culture, repackaged to fit the modern-day definition of nostalgia. On TikTok, anything can be romanticized and glamorized, especially new aesthetics. TikTok highlights the “good” parts of indie sleaze – the glittery residue from a wild night out, the cigarette stubs on the ground, and the reckless bohemian lifestyle. It erases the “ugly” parts – mustache t-shirts, neon snake print shorts – because “ugliness” doesn’t fit the romanticized version of this era. This desire for nostalgia has recently increased, and it often conveniently ignores the fact that things often look better in hindsight. An uptick in nostalgia often originates from shared trauma; for original indie sleaze-rs, that was the aftermath of 9/11. For us, it’s the COVID-19 pandemic. Shared trauma forces an awareness of time, especially how much time we have left. That’s where the nostalgia comes in. The pandemic created a psychological and developmental ripple and its true impact remains unknown. We’re experiencing the social consequences but do not fully comprehend the lasting effects of isolation

and the disruption of normalcy. A fog of uncertainty still lingers. Fear for the future looms. We turn to nostalgia and sentiment and “living it up” in an attempt to connect and experience it “all” before time runs out (all hallmarks of indie sleaze and its inevitable return). Nostalgia evolves into a craving for the normalcy we lost, and we search for it in how we present ourselves to others through what we wear, thereby accelerating trend cycles. Trend cycles used to consist of five stages: introduction, rise, peak, decline, and obsolescence. Now, trends typically undergo three stages: introduction, rise, and obsolescence. These new microtrends usually last about three to five years, but because of the “make more and make it faster” nature of capitalism, they’ve gotten even shorter, now typically lasting only the length of a fad – a few months. That affects real trends, decreasing a real trend’s existence down to three to five years. Increasingly shorter trend cycles inhibit any true resurgence of indie sleaze; indie sleaze originally developed more gradually – it was less dependent on the range of modern social media apps for disseminating its message and aesthetic (it relied mostly on Tumblr), which is why it felt more organic. With the proliferation of social media and these rapid trend cycles, that same slow development is impossible for the new era of indie sleaze; people rush into the moment instead of abiding by indie sleaze’s ethos and appreciating it. And don’t forget – eliminating two steps in the trend cycle is detrimental to the environment as well; trend fatigue is quicker, a new trend arises and production increases (increasing carbon emissions), and clothing piles up in landfills – unused, gray, and forgotten. I have a problem with the current replica of the indie sleaze era because we rely on a constant media presence to disseminate information, whether it be about the country, the world, or ourselves. This constant dependence ensures that everything is curated. Nothing is as “organic” as the original era; it can’t be, given society today and social media’s influence on the trend cycle (an ongoing conversation for another time). If we bring indie sleaze back, one thing is clear, we have to do it responsibly; we have to do it healthily – for ourselves and the planet. l

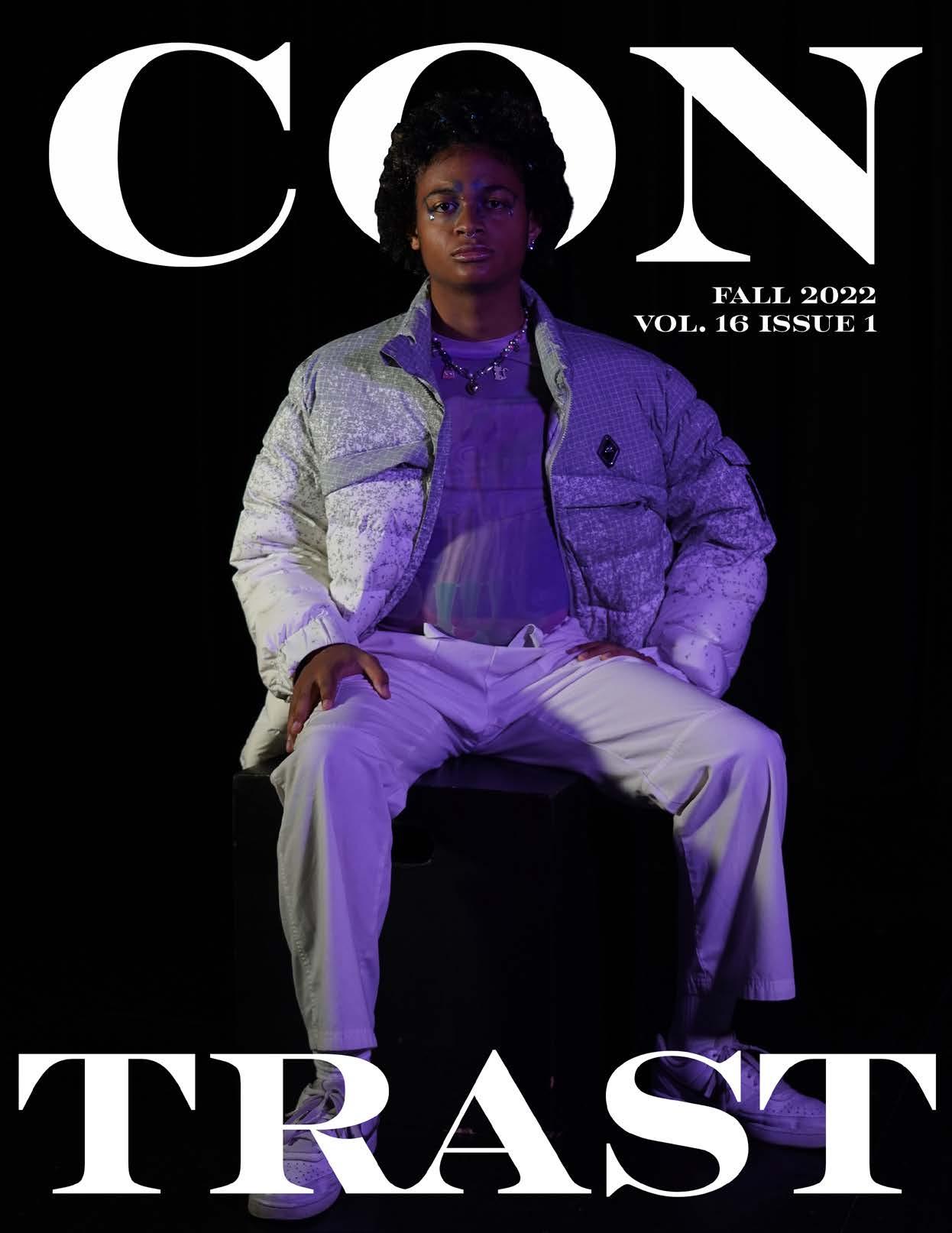

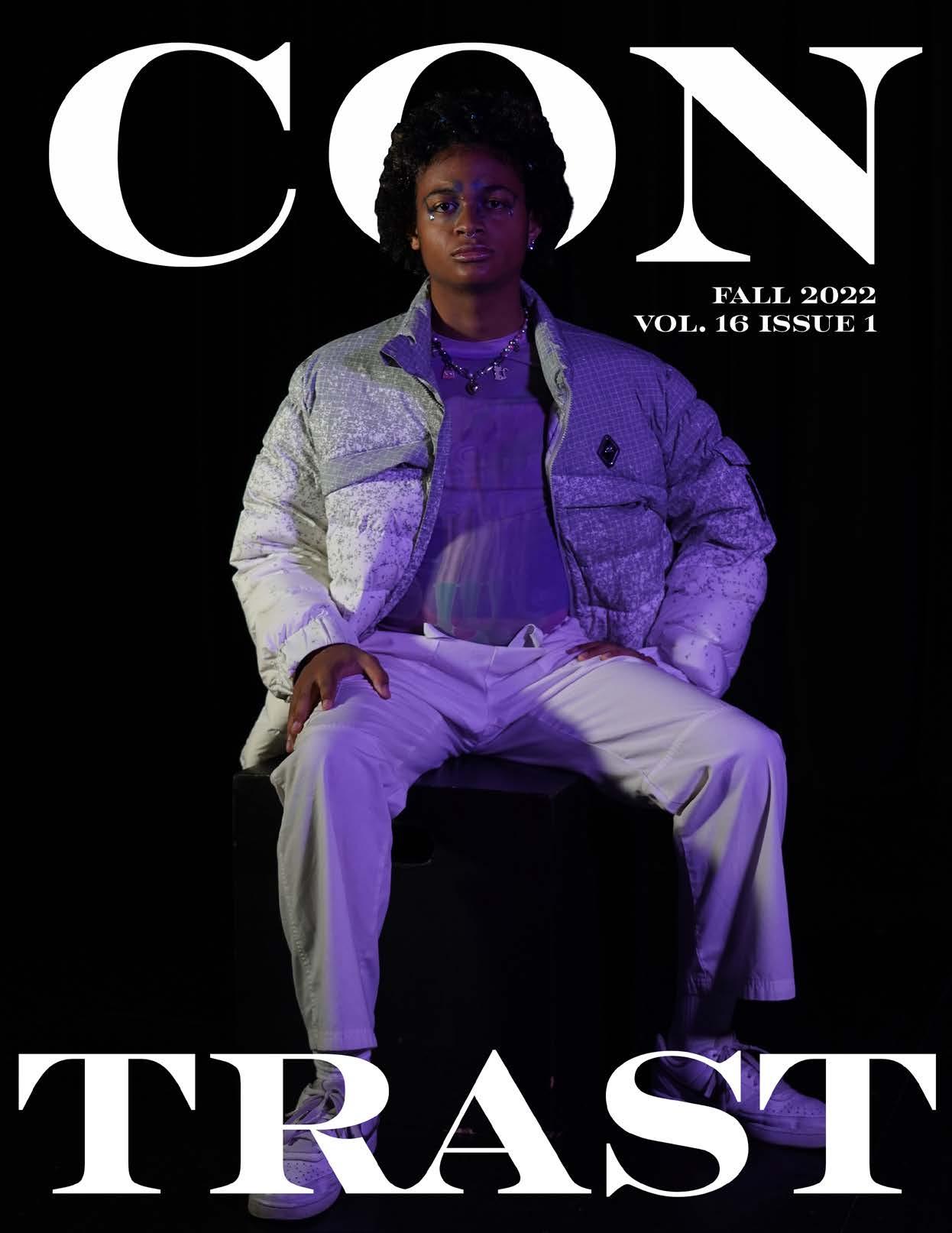

Tech, Music, and Identity: Interview with Digicore Artist Raegun

Over a year ago Koss headphones took over the tiktok homepage. Shortly afterward headphones, of any variety, became an essential accessory. From the Airpods Max, to the return of cords and earbuds, plugging in and tuning out became fashionable. Despite the isolating appearance of headphones, in an era where you may be stopped and asked “what are you listening to” the selection of music or curation of playlists became just as intrinsic to the overall tech aesthetic as the headphones themselves.

In an interview with Raegun, a first year at Vassar and digicore artist, we discuss the overlaps of music, fashion, and identity.

Nicole: So I guess the first question is just like, how did you get into music?

Rae: So the first time I played music, I got a ukulele when I was like seven. And I played a little bit. I wasn’t too good at it. And I played clarinet in fourth grade. I was really good at clarinet. I quit because I was better in my class than everybody. And I felt like the teacher was spending too much time with the sucky people.

Nicole: That’s so funny, my sister did clarinet but now she dropped it and she plays the guitar.

Rae: Maybe this is a pipeline. I picked up bass. Middle school, seventh grade. I picked up bass guitar. And it was because I was obsessed with HAIM, the girls in HAIM. And I thought they were awesome. And then I picked up electric guitar freshman year of high school. In freshman year of high school, I also started playing violin. I started out in concert strings one the first year. And the next year I made the Sinfonia

and I got the most improved award. And then I ended up transferring schools, so I just stopped violin.

Nicole: Do you still play?

Rae: Hell no. I tried senior year. Somebody had their violin in class. I was like, guys I play violin. And then when I played, strange sounds came out. Then I was like woah, like I don’t play violin anymore. Actual music that I record and create is inspired by my brother who is a rapper. Coolcupofwater, baby. And that’s how I got into it. I started rapping in seventh grade. The last rap project I made, I actually am still pretty impressed with that one. It was heavily inspired by like–at that time the new underground New York scene was starting to take off. So it was like, MIKE, Navy Blue, AKAI SOLO, Earl Sweatshirt, like the abstract rap New York scene started to take off and I really love them. And that’s what got me into like passionately

recording music. And then, I mean, the singing was quarantine. Quarantine was when I started questioning about like gender and identity and stuff. Singing helped me release my feelings regarding my identity. And then I start listening to these artists like, specifically the first artist was ericdoa. He’s a singer I idolize. He was one of my first hyperpop artists. And the first song I heard was badgirlsclub. I was like yo, I want to do this. And then people in that community ended up also being trans and gay so I was extremely comfortable and vulnerable with trying new things. So that’s kind of why I started making music, so I could be friends with people. It started more as a friendship thing, and then out of that it grew to something serious. That summer I started listening to, like, ericdoa and like glaive. And then by four or five months later, they were following me. And then we were friends. I’m like, this shit is real. Way earlier that year, like January, I don’t know if you know who Zack Villere is, but I went to a concert and literally at the end of that year we became Twitter mutuals and we became friends and shit. The internet is just so strange.

Nicole: When you meet your idols.

Rae: I know. Right.

Nicole: Okay. So I guess my next question is like how would you self-describe the music that you make now?

Rae: I would say, like, introspective and made for me. But still something you can dance to. I didn’t really like pop music before I started recording it. When I started recording, I started seeing different aspects of pop music, like, intricacies that I really attach myself to. I was attracted to when pop artists, specifically the boys in BROCKHAMPTON namedrop or use a very specific event that only they would understand, but like still make it danceable. So I’d say, like, introspective, but also very fun, very flirtatious.

Nicole: Okay, so how do you balance– do you still make music now?

Rae: Music in college is used more as a coping mechanism than anything. Before I was just making fucking music, like, for fun because I was mad isolated. I went to an all-boys school as a transgirl. I was super isolated, especially during quarantine. So I was just making music because I had nothing else to do. Now it’s more like coping.

Like, when I first got here, obviously for the first month, I wasn’t making music. I was just living life, yeah, but now, out of the past seven days I’ve made music like three or four of those days. Like if you really want to do something you’re gonna find a way.

Nicole: Yeah. Especially, I relate to that. Yeah. Okay, I remember you being the face of, like, digicore, on Soundcloud, So I guess– how would you describe that genre to someone who maybe hasn’t heard of it before? And what do you feel as being like the person who’s the face of it?

Rae: Okay, so the thing with digicore recently, it’s not the same as it was a year ago. The term digicore was professionally coined by a friend of mine. Her name is Billie. And she works with SoundCloud and she was in our community for a long time before. And we use the term digicore because originally a bunch of us were getting placed in the Spotify Hyperpop playlist and then we’re like, this doesn’t make sense because like we’re hyperpop and we’re mostly like trans, like people of color and stuff like this. But also there are like these white artists that are being prioritized over us, but they’re still considered hyperpop and– there’s just like this clear disconnect

with that. So Billie decided to run with the term digicore which is not necessarily for a genre, but a specific scene of people. We’re mostly based around Discord calls so it’s more like a scene. But like now it’s not how it was before. It’s not much of a community anymore, I think because it got so much like attraction and recognition that it’s not as community based. So now I’d say people use the word digicore to describe internet music or any music that’s somewhat emo-esque and adolescent and a little electronic (it doesn’t even have to be electronic). It’s not what it meant two years ago– like we used to have collectives. So I was in the collective called Noheart and there’s me, kmoe, funeral, mental, blxty and then there’s GraveeMind, which is actually still a popular collective. There are still collectives now, just not necessarily as active. So it was like a much more formulated thing. But now everybody’s getting older and we’re growing up and doing things so it’s not like that anymore. If I had to give a few people the spotlight for digicore, I’d definitely say ericdoa, midwxst for sure. And angelus. And juno. But being considered one of the faces of digicore has been one of the greatest things to happen to me. It gave me a purpose. Getting messages from kids all over the

world telling me how much my music meant to them… It feels all too real and I’m just forever grateful to know such lovely musicians and get to call them my peers.

Nicole: Awesome. Thank you. Okay. So since Contrast is a fashion magazine, how would you describe, like, your personal style and do you feel like kind of the way that you make music also meshes with the way that you personally dress yourself or style things?

Rae: That is interesting because it used to a lot more than it did. If you go through my Instagram archive, when I was rapping and making music specifically about being extremely pro-black, you could see that I was wearing all these different, cultural vests with multiple patterns and colors. Wore political shirts, like my ASSATA IS WELCOME HERE shirt. I still have that actually. But now actually, yeah, I guess because I developed my personal identity with transness through my music and of course I try to express that when I dress and how I like to present myself. So yeah, there definitely is that like connection, but mostly through femininity. I try to be as feminine as possible.

Nicole: Okay. Do you have

anything that you just came into this wanting to talk about that we haven’t talked about?

Rae: Yeah. About my music that I end up releasing whenever. It’s going to be very different from what it was before. The break I’ve taken from releasing music was mostly because I started realizing that I’m growing up, so you can’t expect me to be stuck on the same things. Back then, music was a lot more careless for me because it was more community based and made from energy and spontaneity. Now I’m taking a much more personal and mature approach, I guess. I just think it’s going to be a surprise.

Nicole: I look forward to it.

Rae: I will never be able to kill off the traditional hyperpop elements of my music because it’s kind of what makes my music feel special. But it’s definitely going to be a lot different.

x Minecraft

Technology and Fashion: Burberry

by Abigail StraussA basic crewneck sweater can be grabbed from the thrift anywhere from $1 to $10 depending on where you go. Want to buy one new? Try Amazon for prices near thrift store level, or maybe head to the mall and find a brand-spanking new one lined with a fleecy-feeling fabric and cute embroidered details for $50. You could also go online to the Burberry website and grab their Monogram Motif Print Cotton Sweatshirt for a mere $1,000 from the Burberry x Minecraft collection.

But look around, this collection isn’t limited to physical pieces, oh no. Instead, it includes virtual options that come in the form of skins for your Minecraft characters. To obtain these, your entire Minecraft world will become augmented with Burberry as you play through the “Burberry: Freedom To Go Beyond” adventure game. Once in-game, you can choose items of clothing (i.e. “skins”) for your character to wear, all of which have real-world counterparts – so you and Steve can match, duh. The game also incorporates elements of the overall Burberry aesthetic with colors and patterns mimicking the clothing designs, all of which you encounter as you play through a rescue mission in which you restore an industrialized, dystopian London to its lush, forested former self. If you’re thinking, “uhhh what?” You’re not alone. Who asked for this? The answer lies in fashion trends

from recent years, which have pushed toward the inclusion of new technology on the runway and in stores.

Take the SS23 Coperni collection and its already iconic Bella Hadid spray-on dress display. This show quickly made headlines with innovative spray-on fabric capturing the public’s curiosity and imagination. This display (for those of you who missed the cultural moment) began when Hadid entered the runway in nothing but a string bikini and made her way to a platform on which she stood while a white dress was sprayed onto her body. Once applied, the dress was manipulated to finish off the design and sent down the runway. The web-like material used to cover her was made all the way back in 2003, but Coperni chose to exhibit it now to fit with their brand’s essence of innovation, which has been showcased in past collections, such as in their line of glass handbags in FW 22.

The new materials sweeping fashion go far beyond spray-on fiber, extending into steel and resin manipulated through 3D printing – a technique that has long been employed by artist and designer Iris Van Herpen. Though her designs have got-

ten press before, this year’s 2022 Met Gala, America: An Anthology of Fashion, released her style to a broader audience than ever before through actress and singer Dove Cameron. The look featured a 3D printed masterpiece, with tendrils coming off Cameron’s arms posed to mimic the large bustles of early American fashions. Corseture was also formed through intricate bodice boning, showing how modern technology can be used to recreate that of old.

Technology can also create completely new silhouettes that defy laws of physics, virtually that is. DRESS X is a company that offers its customers this opportunity, selling designs with floating elements or lights that seem otherworldly. Like the Burberry x Minecraft collection, however, this doesn’t come cheap. DRESS X’s lowest offer is $24 for a pair of sheer glasses that can be digitally uploaded to photos, and while that price might not seem too steep, glasses are merely an accessory compared to something like their Intergalactic Freedom Dress, which stands at a whopping $1,500. Nothing in your cart will be physical on checkout, with DRESS

X prompting you to upload a photo instead, which the item you chose can then be applied to. Once created, your photo allows for you to build new outfits without creating any of the waste so closely associated with fast fashion. There are plenty of arguments against these strange virtual fashions, pointing to their often ill-fitting forms and obviously virtual appearance, yet as technology improves so will they.

From digital To physical

From Burberry x Minecraft to Iris Van Herpen the fashion industry has been exploding in technology-powered design in recent years. Through combining the real world and the artificial, collections such as Burberry x Minecraft and companies like DRESS X are starting to blur the lines between fashion and virtual reality. On the other hand, designers using technology in the real world have begun to blur lines in the opposite way, bringing reality-defying elements off the screen. As the industry continues to develop, technology and fashion will continue to become more and more synonymous, and we will have to face the inevitable collision of the virtual and real worlds.

COATCULTURE

by Keira DiGaetano

by Keira DiGaetano

Canada Goose. Oversized denim (with patches). The Aritzia-inspired black leather jacket plaguing the wardrobes of aspiring “it girls” everywhere –– as I write this, my friend’s is draped on the chair behind her, poised to be shrugged on with ease at the first shiver. From autumn to spring, until the weather turns too undeniably warm to wear anything more than a tank top, jackets are universally linked with the qualities you want the world to recognize you for. A coat is your own personal billboard upon which to signal that you fit in with a certain community –– think the aforementioned sleek, feminine leather jacket versus the studded, cropped and torn alternative –– both leather, representing distinctly different identities. Think of the fear you feel when you set your coat on the sticky pile at the back of a house party, to lose this personified possession would be an irreconcilable loss.

I spoke to four of my peers about their own pieces of distinctive outerwear, to ask them what exactly

is so compelling about the jackets they armor up with each morning. Evelyn recounts the purchase of her puffy purple North Face with fondness –– “my friend Avery was considering buying a new coat at Aritzia, in which case she would sell her old black Aritzia coat to me for fifty bucks. I was really stoked about that, but then after forty minutes of going back and forth, she decided to keep her jacket. I was bummed, but then when we left we walked past North Face, and I decided to go in. There she was. It came in red and blue too, I think, but purple was the only possible option. I knew someone who had the blue and didn’t want them to think I was copying them.” She reflects that “since I got this coat freshman year it definitely represents my construction of my Vassar self, too” –– the identity that comes with her coat is directly linked to her identity on Vassar’s campus.

Another friend, Zoe, remarks on what makes her particular black leather number special to her –– “I got it around a year ago at Aritzia,

and was debating between buying it versus an oversized jean jacket— on the counsel of my friend Abigail, who thought the jean jacket was a tad too ‘2014 Sky Ferreira Tumblr’ (her words), I went with the leather jacket. And it was the right choice! I wear it all the time. I like that it’s not the traditional moto/biker cut, and that it’s spacious enough that I can layer sweaters underneath.” On the other hand, Theo appreciates his vintage blue wool coat as the current evolution of coats past, “newly branded as my signature coat, to replace the 1960s white wool sculpted coat I wore all of last year,” and “warm, but not warm enough to merit versatility,” which he loves–style over substance. Finally, Cecily mourns a denim jacket that she wore out one night –– “as I went to leave, I noticed the corner where I’d stashed my jacket was suspiciously barren. With reckless abandon, I searched the emptying room, now unsettlingly lit by the overhead sconces instead of the colored strobes I’d grown to love. As I walked home that night,

protected from the night air only by the lingering effects of tequila soda, I felt an almost inappropriate grief.” The loss of this jacket, its warmth and familiarity, was incomprehensible to her.

As far as my own leanings, I find myself rotating between three coats of distinct significance. I reach for each of them for distinct purposes, even if the unique, sentimental role each one of them plays is invisible to the naked eye. One, a dark green fleece that used to belong to my grandmother, is my most frequent pick. It’s a solid color, not flashy, lightweight and nondescript enough to wear around campus and then to a house concert with no transition time –– to leave on that aforementioned pile while still knowing ex-

actly which coat is mine. The memories of visiting my grandmother are invisible to the crowd, it’s Patagonia and actively pilling, but my grandma was an artist, and I like to imagine that giving the coat a second life in artistic spaces gives it a sort of cyclical sense of fulfillment.

My second choice coat is wooly, oversized with big round buttons, a blurry plaid in shades of pink, orange, and green that I proudly say I thrifted for five dollars any time someone asks. If I want to impress, to look my most art-teacher, this is what I reach for –– it reminds me of my semester abroad, of running around England aimlessly while my classes were on strike, of rain soaking through to my skin (it’s not a very sturdy coat). Coat number three is the one a friend mentioned

when I told her I was writing this piece, a black tapestry coat with embroidered flowers, the sort of “I’m buying something I actually need, so I’ll let myself also buy something silly” purchase, and then of course I wear this coat way more than the practical item. My jackets make me feel safe, protected. When zipping them up, I feel a sense of control that is beyond physical possibility, like I hold influence on how I am perceived by strangers. Regardless of mood, time or place, putting on the same coat is an act of intimacy that soothes us, merging familiarity and style into one cohesive image for the rest of the world to see.

AUTISTIC PANTS AUTISTIC PANTS

by Tao Beloney

Cards on the table, this is a nepotism publication – Contrast editor Anjali Krishna saw a pair of pants I was wearing and asked me if I wanted to write about them, I responded that I had no idea what I’d write, then a month later she asked again and I agreed, still not knowing what to say. The pants in question are a pair of Rustler jeans I found about four years ago at the Salvation Army on Park and Blanding in my hometown of Alameda, California, which I heavily repaired with the remnants of another pair of jeans that I’d long since grown out of. They weren’t an art project, not self-consciously at least; I did it because I wanted to, because I enjoy sewing, and I wear them because I like them. That’s not to say I’m not proud of my work, but I am having difficulty finding anything to say about these pants beyond “I like them.”

Venerable camgirl and philosopher Natalie Wynn begins her inquiry into beauty by asserting that it begins in childhood with “pure aesthetic bliss.” So, I suppose “I like them” is as good a starting point as any. Wynn’s point of departure was her childhood experience of

thinking that the gemstone collection at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History was pretty, but for me, the bliss of these pants begins not with visual beauty but with their sensation. It begins with the autistic joy of simple, repeated actions, the humble running stitch and the emergence of the repeating geometric patterns, the satisfaction of the physical sensation of pulling on thread. Making the pants was a stimulating, meditative act, not done for the final product but really out of boredom, a need to do something, anything with my hands.

I was inspired at the time by sashiko, a traditional Japanese textile art dating back to the Edo period that uses decorative embroidery to reinforce garments. Because in medieval Japan indigo cloth and white thread were cheap and abundant, the distinctive sashiko look is stark white, repeating, geometric patterns against a dark blue backdrop. Nowadays, both in and out of Japan, it’s typically done on denim. Since the American occupation after World War II the Japanese have had a somewhat macabre (to my eye, at least) fascination with Ameri-

can fashion, combining military, Western, and Ivy influences into a distinctive style sometimes known as “Japanese Americana,” which has recently been creeping back across the Pacific in the form of men’s fashion. When mending these pants I had no idea about Japanese Americana or the long history of cross-Pacific fashion exchange between Japan and America. I was inspired by a couple of cool Filipino Instagram accounts of dudes who will repair your jeans with sashiko for money.

Wynn’s point about beauty is that aesthetic values are distilled over time from childlike bliss into a “mature” set of socially acceptable tastes. We might call this “refinement,” but to many it is restrictive; Wynn observes that this distillation is one way in which queerness is suppressed during adolescence and into adulthood. This is very similar to the phenomenon of autistic masking – we all learn as we grow older how to approximate allistic-ness, at least enough to make it through job interviews, we learn to stim in private, to hide – “mask” –our autisms. This is one of the rea-

sons I like those pants so much – because they are a physical embodiment of some thing that is ordinarily invisible. But I cannot escape the reality that they are at the same time an amateur bit of Japanese textile art. Even as we “refine” our tastes, we become in creasingly aware of the social, cultur al, and historical implications of the things we enjoy and aesthetic bliss becomes impossi ble to maintain. Is wearing Carhartt stealing blue-collar valor? I think that’s reductive, but, like, it’s not not blue-col lar appropriation. There’s a somewhat apocryphal sto ry about Japanese Americana that I find enlightening, and also kind of funny. Sometime in the mid-to-late 70s, a Jap anese fashion designer, having read the 1965 seminal menswear photography book Take Ivy (does one “read” photography books?), embarked on a tour of Amer ican college campuses looking for inspiration for his work and was shocked to find American students dressed not like Ralph Lauren models but like students in the ‘70s. The thing about Jap anese Americana is that Ameri cans don’t dress like Yale students in the 60s anymore unless they’re doing Japanese Americana. It’s a picture of WASP America filtered through two layers of myth – the

ments or vocalizations that may be socially unacceptable or simply confusing to allistics. It is, to the autist, one of life’s simplest pleasures, but you quickly learn as you grow older that it must only be indulged in private, that your physical comfort must always be secondary to the social comfort of the people around you.

The first thing I thought about when I sat down to write this was Leo Tolstoy’s 1897 book What is Art? which I picked up on a whim in San Francisco around the same time I started working on my pants (I was not a terribly fun 17-yearold). Tolstoy rejects aesthetic beauty as a defining characteristic of art and concludes that art, fundamentally, is anything at all which conveys emotion. The question then is what emotion these pants express: sensory joy, stimulation. But even that cannot exist in a

vacuum. In a way I’m privileged that my stimming can be done in a way that produces socially acceptable “art,” privileged that it can be externalized publicly at all. More often than not autistic aesthetics are the subject of intense ridicule, the sort of thing that gets you bullied in grade school and makes you unemployable in adulthood.

Most modern philosophers don’t actually like Tolstoy’s What is Art? very much. They think it’s more important for what it rejects than for what it asserts. But I think he was on to something. To Tolstoy, aesthetic proceeds from emotion, and in these pants, aesthetic proceeds from stimming, and that feels to me like an extremely autistic thing for aesthetic to do. And I thought, when I set out to write about them,

pants may be autistic, but they also embody a long, complicated, and frankly kind of strange political history of violence and artistic exchange between Japan and the United States. And even as they embody autism they do so in a way that is socially acceptable to allistics, that is, through fashion, and in that sense they are diminished as a form of embodiment.

In some ways Anjali’s initial question was the death of the pure bliss of those pants, though really I had most of this article in the back of my mind already. I wonder how much of my resistance to writing about them was motivated by a desire to maintain that bliss, as if the act of writing something makes it real. There is an impulse, I think, when discussing fashion and aesthetics to think of it as a kind of personal expression, an impulse that often sits alongside a rejection of outside influences, typically trends. It’s an impulse that sits uneasily beside discussions of tact and cultural appropriation, as well as discussions of fashion that try to analyze it as art. Cowards and fools will sometimes try to maintain their bliss by arguing that analyzing media ruins the fun, though I must confess I’ve never really understood this position. Isn’t analysis fun? And what do they gain by neutering art, denying it its ability to impact and influence? But regardless, the fact of the matter is that basically all engagement with the world requires some degree of reconciliation between aesthetic bliss, personal and emotional expression, social mores, and more – everything exists in context. And I think my pants are beautiful, not in spite of their context, but because of it. I just wish they fit better.

The New Americana

Exec Board

EdiTOR IN CHIEF

Nick Gayle

h Treasurer

Zarina Guefcak

h pHOTO Gwen Ma Jade Hsin Lily Tarrant h

STYLE

Carissa Kolcun Lily Tarrant Yasmin Mohamed Zarina Guefcak

BEAUTY

Carissa Kolcun

h fILM Jade Hsin Mareme Fall h Layout

Freddie von Siemens Gwen Ma Morgan Stevenson-Swadling h

eDITORIAL & Media

Anjali Krishna Henryk Kessel Julia Colon Kiera Digaetano Natalie Colletta

Contributors

Writers

Abigail Straus Anjali Krishna Carissa Kolcun Lindsay Shih Tao Beloney Wyatt Keleshian h

Photographers

Abigail Straus Alisha Arden Gwen Ma Jade Hsin Mareme Fall h

Models

Aanzan Sachdeva Amber Huang Anjali Krishna Becca Spence Celeste Weidemann Estella Zacharia Grace Fox Ila Kumar Mareme Fall Neariah Leiner Presley Wheeler Rae Sophie Wigington Wren Reardan Yasmin Mohamed Zerah Ruiz