2 minute read

Met historische foto's

Voor de lezers van De tweeling van Auschwitz

Eva Mozes Kor en Ik ontsnapte uit Auschwitz

The first time I began to feel that there was anything wrong—my first experience of being singled out, being different, being perse- cuted—was my first day of school, in 1934.

van van Rudolf Vrba

204,000 Jews all Jews have big noses—and a way of saying: “If it’s annoying, a Jew must be the cause.”

Children of this age were typically taken from their parents and sent to be murdered at the Chelmno, Poland, extermination camp.

Like every other kid, I was frightened, a little apprehensive. I was six years old now, and I was going out, into the unknown world, away from my mother and father for the first time, ready or not. My parents walked me to school; I was carrying, very seriously, a little leather backpack containing a tiny blackboard, a piece of chalk on a string, and a sponge to use as an eraser. I was wearing knee pants, stockings and a little hat, like a beret, which identified me as a first-year student.

Like all the other children, I carried a huge cardboard cone that my parents had given me. It looked like a megaphone or a dunce

By setting these stones so they stick up from the surrounding sidewalk—so you are actually likely to stumble over them—Demnig turned this custom on its head. He turned it from a rude saying into a daily reminder of Germany’s guilt and responsibility—a persistent, permanent tribute to what the German people did to the Jews and other persecuted minorities.

Document: Unites States Holocaust Memorial Museum memorial

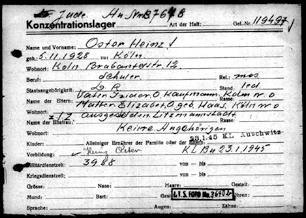

Henry (Heinz) Oster’s German SS file card recovered by the Allies from the Buchenwald concentration camp (Konzentrationslager) files. It details his birthday (November 5, 1928), home address (Brabanterstrasse 12, Koln (Cologne), his parents (Isidor and Elisabeth Oster), his detention in Łódź (called Litzmannstadt by the Germans), his detention at Auschwitz and his arrival date at Buchenwald (23.1.1945). It also shows both his identity numbers: the number on the upper right, 119497, was his prisoner number, displayed on his blue-striped prisoner jacket. The handwritten number at the top, B7648, is the number tattooed on Henry’s left arm.

Henry Oster en Dexter Ford ontmoetten elkaar in Californië in de optometriepraktijk van Henry. Hun afspraken werden gesprekken, hun gesprekken een vriendschap. Op een dag vroeg Dexter naar het getal dat op Henry’s arm getatoeëerd stond. Het boek De staljongen van Auschwitz is het resultaat van die vraag.

Blocks”

I remember sitting on my bunk in the former SS barracks answer- ing question after question in Yiddish as my interviewer wrote down the answers on his clipboard. I still have the report he made that day. It sounds strange, but it felt good to have my life set down on paper—as if I’d stopped being a human being for a time, but was now coming back into the land of the