4 minute read

Drought

IN A STATE OF DROUGHT

EXAMINING THE LOCAL EFFECTS OF CALIFORNIA’S WATER CRISIS

AS PALO ALTO HIGH school students walk along the path dividing the two halves of the Quad, they are met with patchy, albeit green, grass on one side and almost completely dry grass on the other. Brown lawns, drought-resistant crops and water regulation laws in residential areas are part of telltale signs of the worsening drought in California.

Water levels have dropped from 20 million acre-feet in 2020 to a current capacity of only 33 percent, according to The State Water Project. Around 80 percent of California’s water is used for agriculture according to the California Department of Water Resources. This is particularly damaging for local farmers like Rye Muller, who said he decided to farm 50 fewer acres this year — a 10 percent cut from what he would in the average year.

“We rely on the reservoir [which] released no water, so we were relying on natural flows which are at basically nothing now,” Muller said. “So we are deciding right now, how much to cut back going into the fall.”

While Muller is trying to predict future water supply, he also underscored the importance of rain.

“If it doesn’t rain, there’s going to continue to be lower and lower amounts of water in our creek [and] in our watershed,” Muller said. Muller also feels that this drought is worse than he has seen before.

“I was still a young guy but I feel like this drought is different because … the reservoir from previous years [was] way more at a higher capacity, whereas now, if it doesn’t rain, there’s going to continue to be lower and lower amounts of water in our creek [and] in our watershed,” Muller said.

While farmers have been hoping for rainfall, they have also taken matters into their own hands.

“We’re doing more cover crops and mulching, [and] more compost than ever,” Muller said.

Mulching is a technique to preserve water, where wood chips are used on top of the soil to cover crops, which helps enhance and protect the soil. However, these efforts, while effective, come at the expense of farming profits.

“Farmers have to spend more mon-

“But I think another dry year and we’re gonna be making more ey getting water, either by drilling into drastic conservation.” the groundwater or getting it trucked in,” AP Environmental Science teacher Nicole — RYE MULLER, local farmer Loomis said. “So food potentially becomes more expensive.” John Burkhold, a dentist and bee keeper, has also felt the increased price of water in his own residential home. “Last five, six years, it’s been affecting us because we didn’t water more,” Burk“Farmers have to spend more money getting water ... so food potenhold said. “Five, six years ago, water bills were really high and that was a concern, and we sort of cut back tially becomes more and make sure we expensive.” weren’t planting other water-thirsty new plantings. We — NICOLE LOOMIS, AP Environmental cut back watering science teacher on our lawn.” Beyond the price-based regulation of water, Palo Alto is also attempting to mitigate the harms of drought.

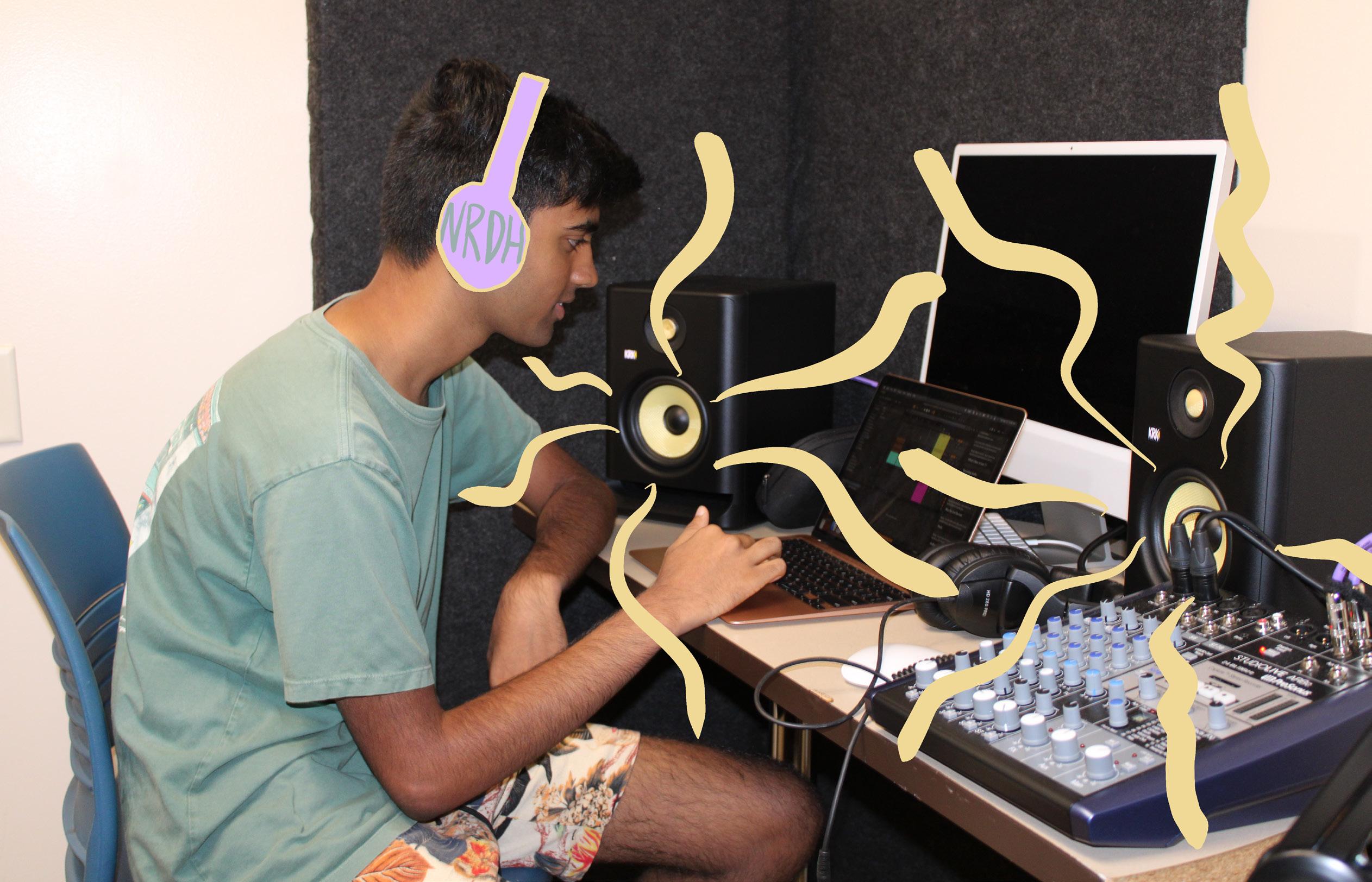

TWO HALVES — Palo Alto High School seniors Isaac Kirby (left) and Drew Nagesh (right) on the Quad during 7th period. “If one person limits their usage of water, it won’t make a difference, but if more and more people do so, then over time there will be a big impact, and we should all do our part,” Kirby said. Photo: Ines Legrand

“The City is developing a One Water Plan, an integrated water resources plan that will address how the City can mitigate the impact of future uncertainties such as severe multi-year drought, changes in climate, water demand, and regulations,” City Sustainability Programs Administrator Linda Grand said. “This plan will be a 20year adaptable roadmap for implementation of prioritized water supply and conservation portfolio alternatives.”

Additionally, the city has recently implemented a watering schedule, forcing odd addresses to water use only Mondays and Thursdays and even addresses to water use only Tuesday and Friday.

This is all to make sure that non-residential groups use water responsibly, Grand said.

“The city does not allow wasteful water practices such as broken irrigation sys-

tems,” Grand said. “City staff investigate water waste reports and educate community members about drought regulations.” While imperfect, farmers like Muller are grateful for the city’s efforts. “They can’t make it rain more, unfortunately, which is ultimately what “They can’t make it rain more ... but there are programs that’ll would be the biggest relief to us,” Muller said. “But there are programs that’ll help fund faster help fund faster drought relief.” drought relief.” Right now, only time will tell — RYE MULLER, local farmer the effectiveness of a concerted city and farmer plan, and whether rainfall will pick up in the coming years. “Assessing whether or not we’re going to be able to carry crops through this fall is where we’re at,” Muller said. “We’ve had enough water to get through this summer, but another dry year and we’re going to be making more drastic conservation.” v