IN THE PRESENCE OF ABSENCE

by Briar Craig

The artist performs only one part of the creative process. The onlooker completes it, and it is the onlooker who has the last word.

Marcel Duchamp

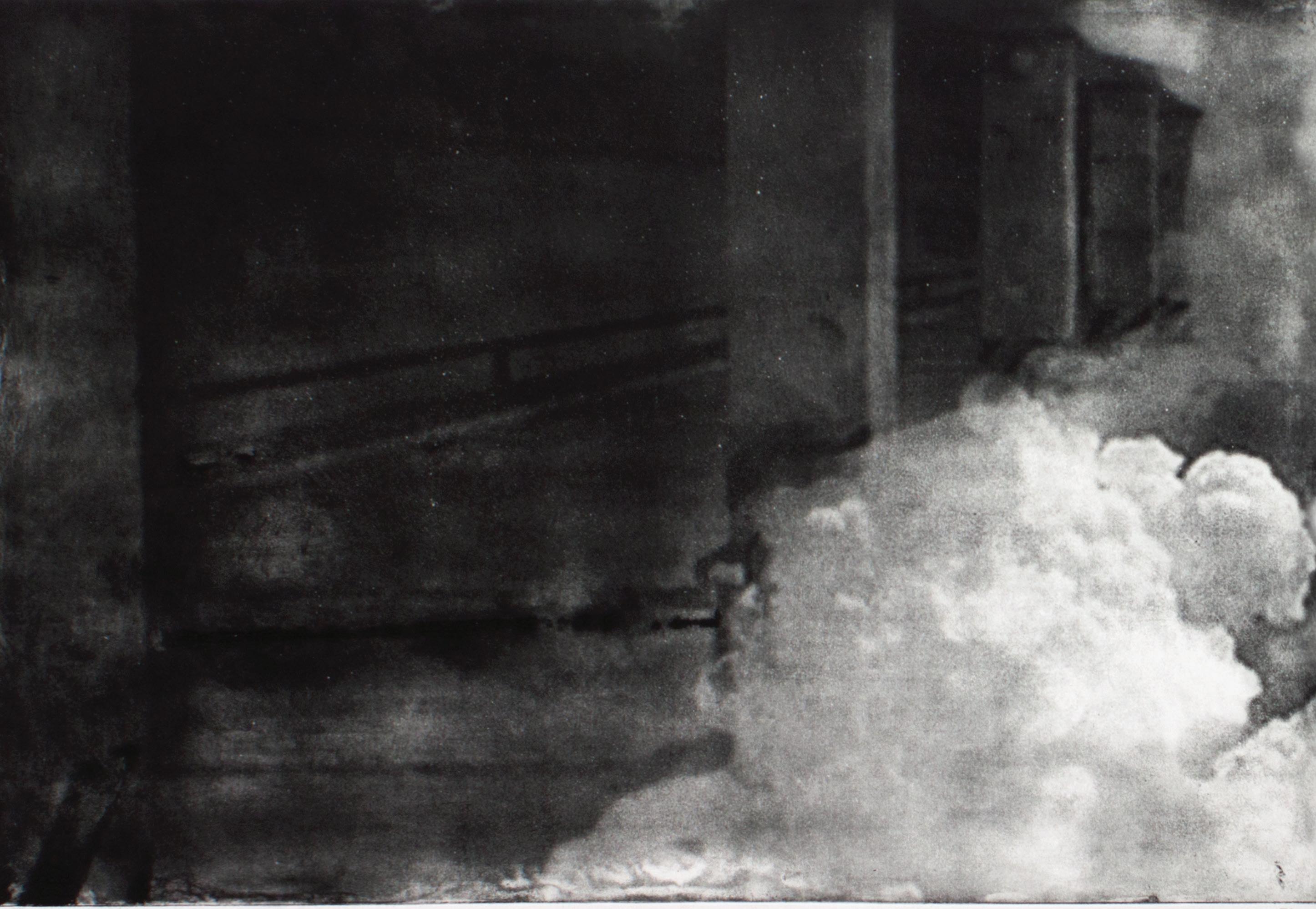

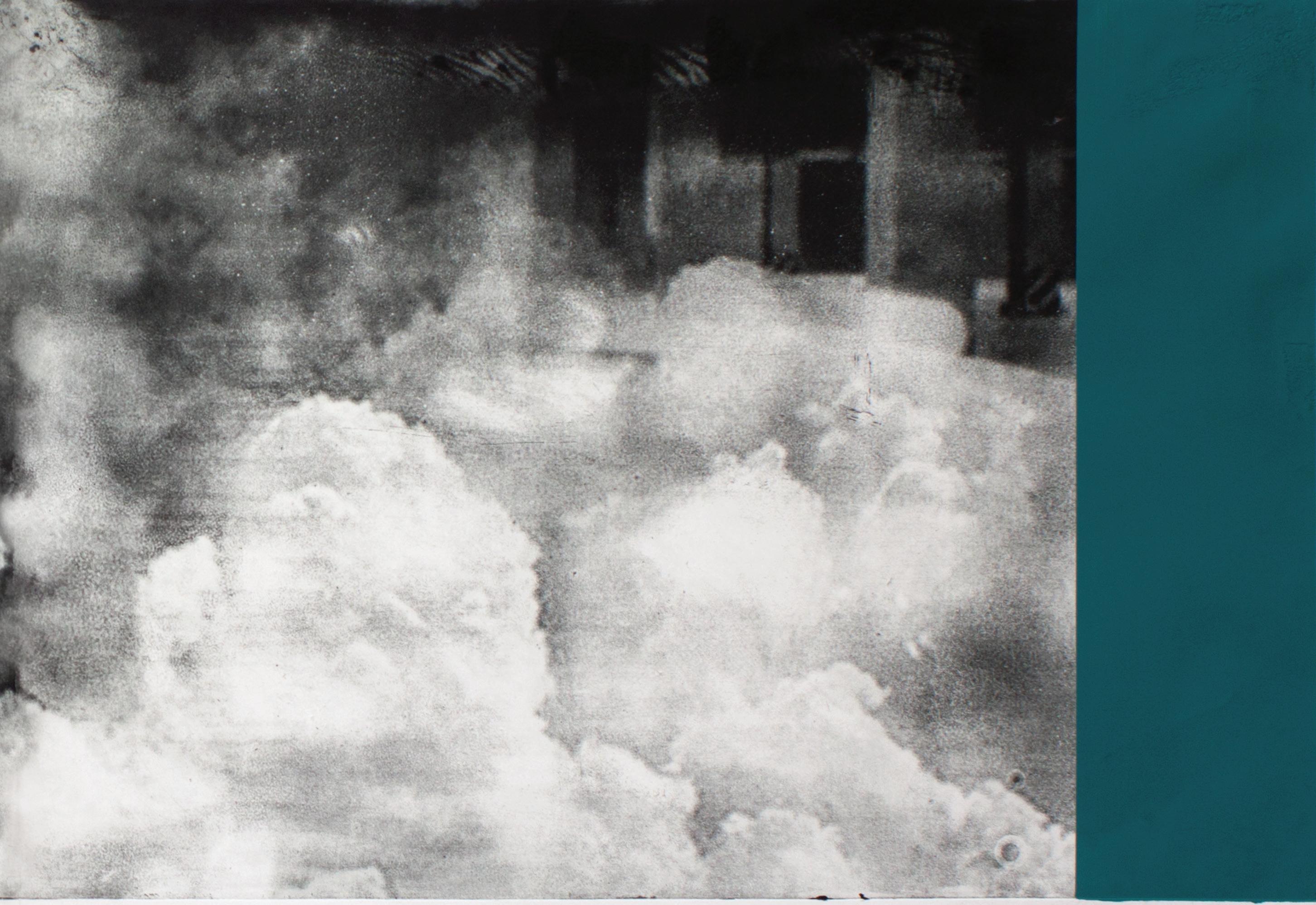

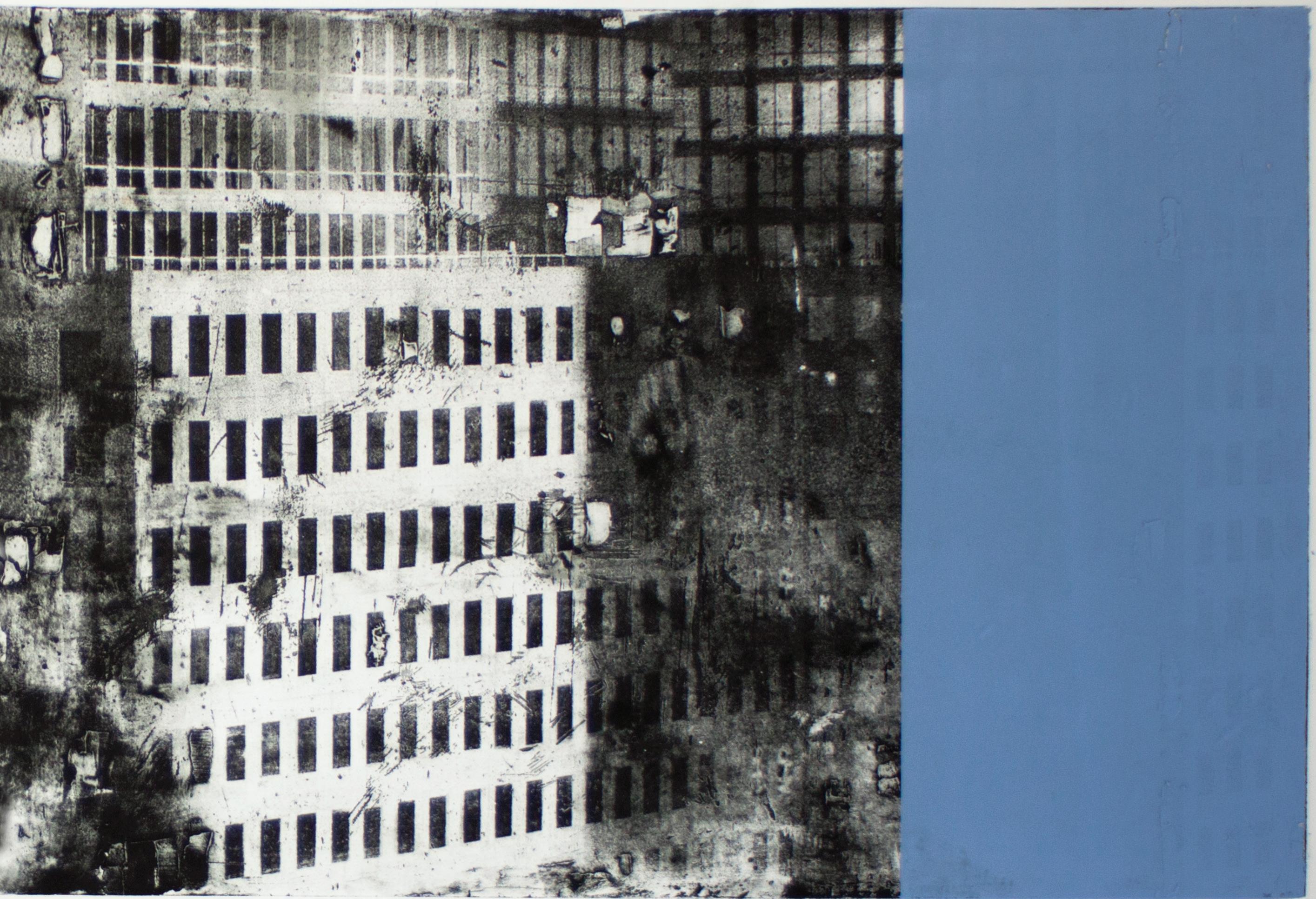

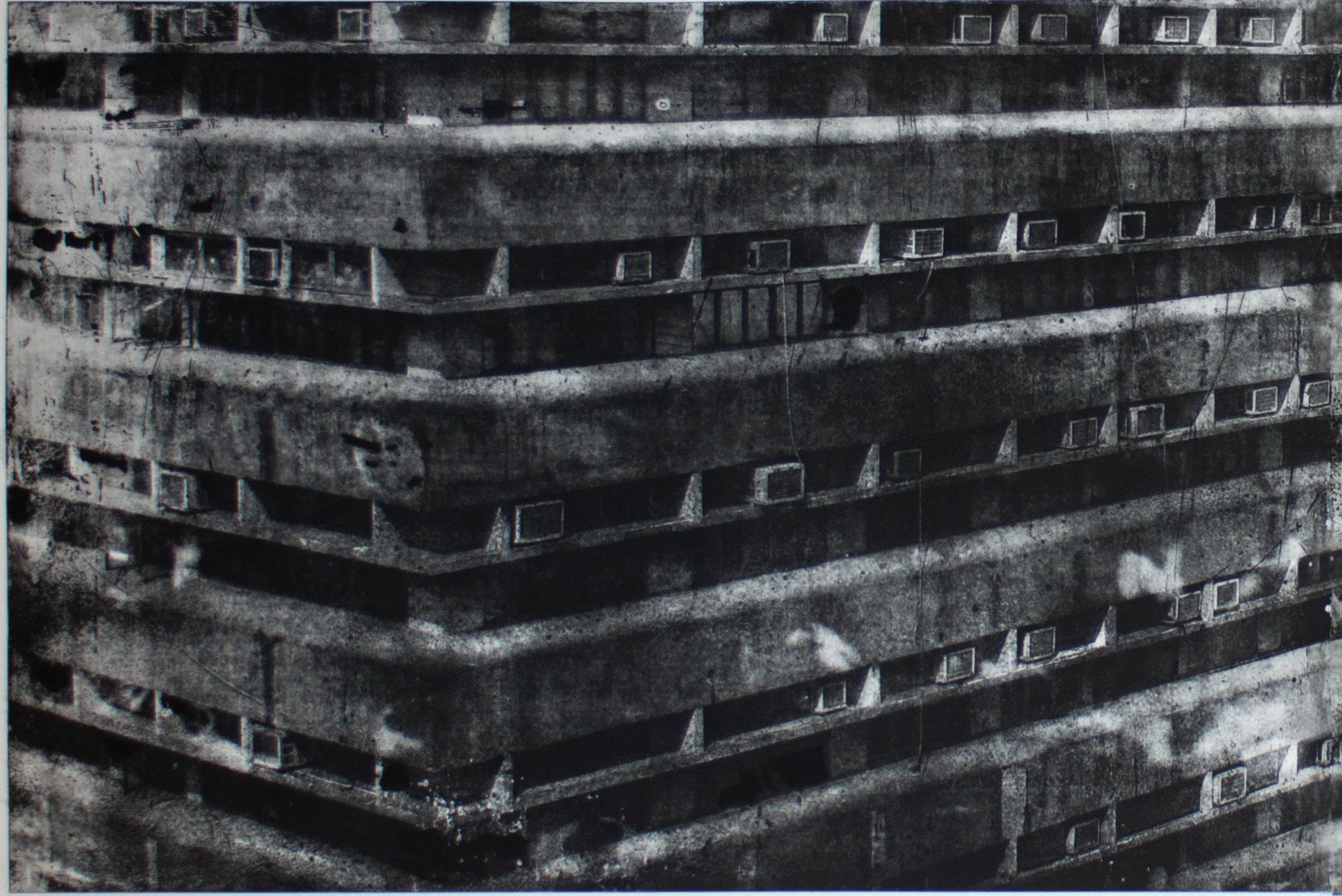

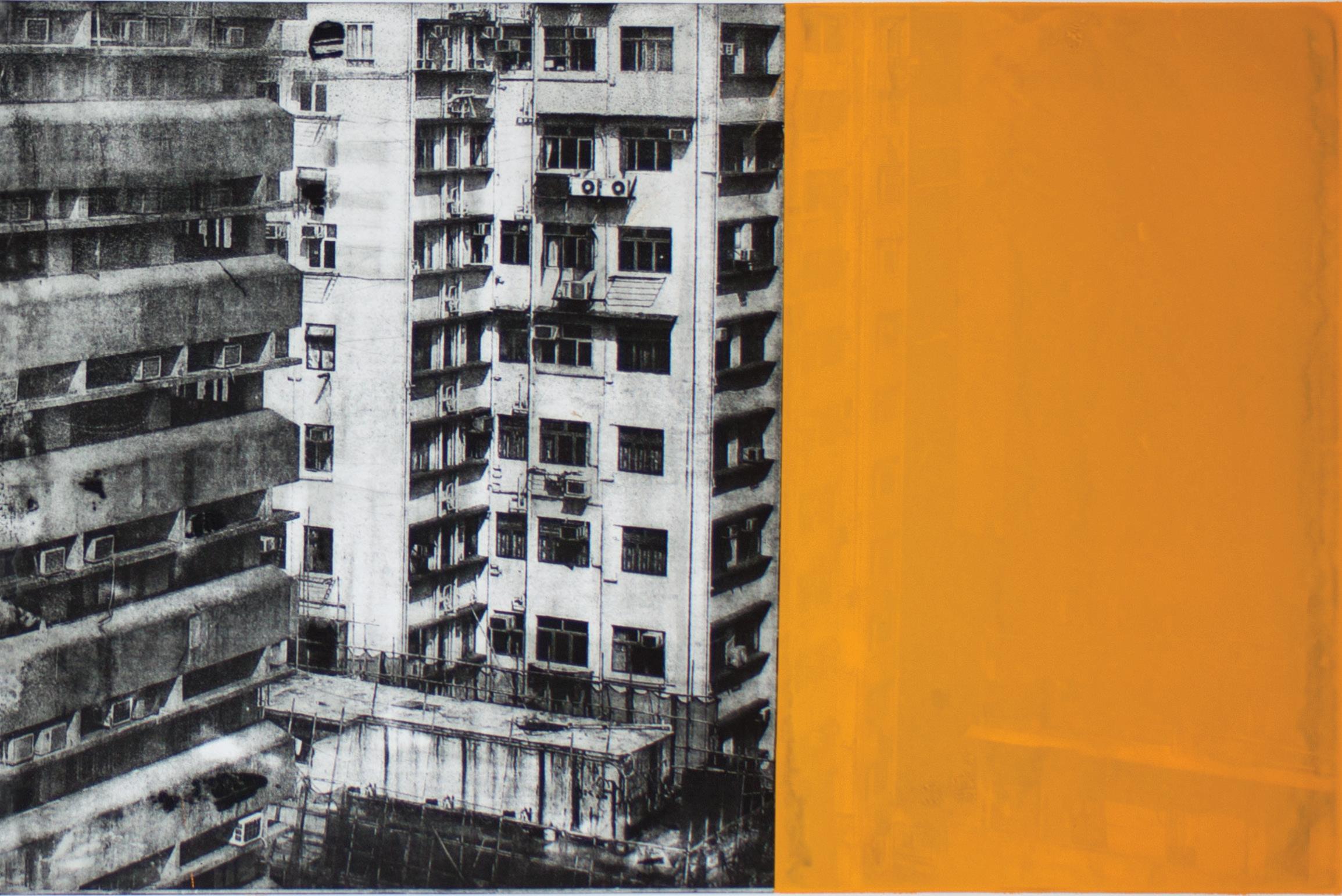

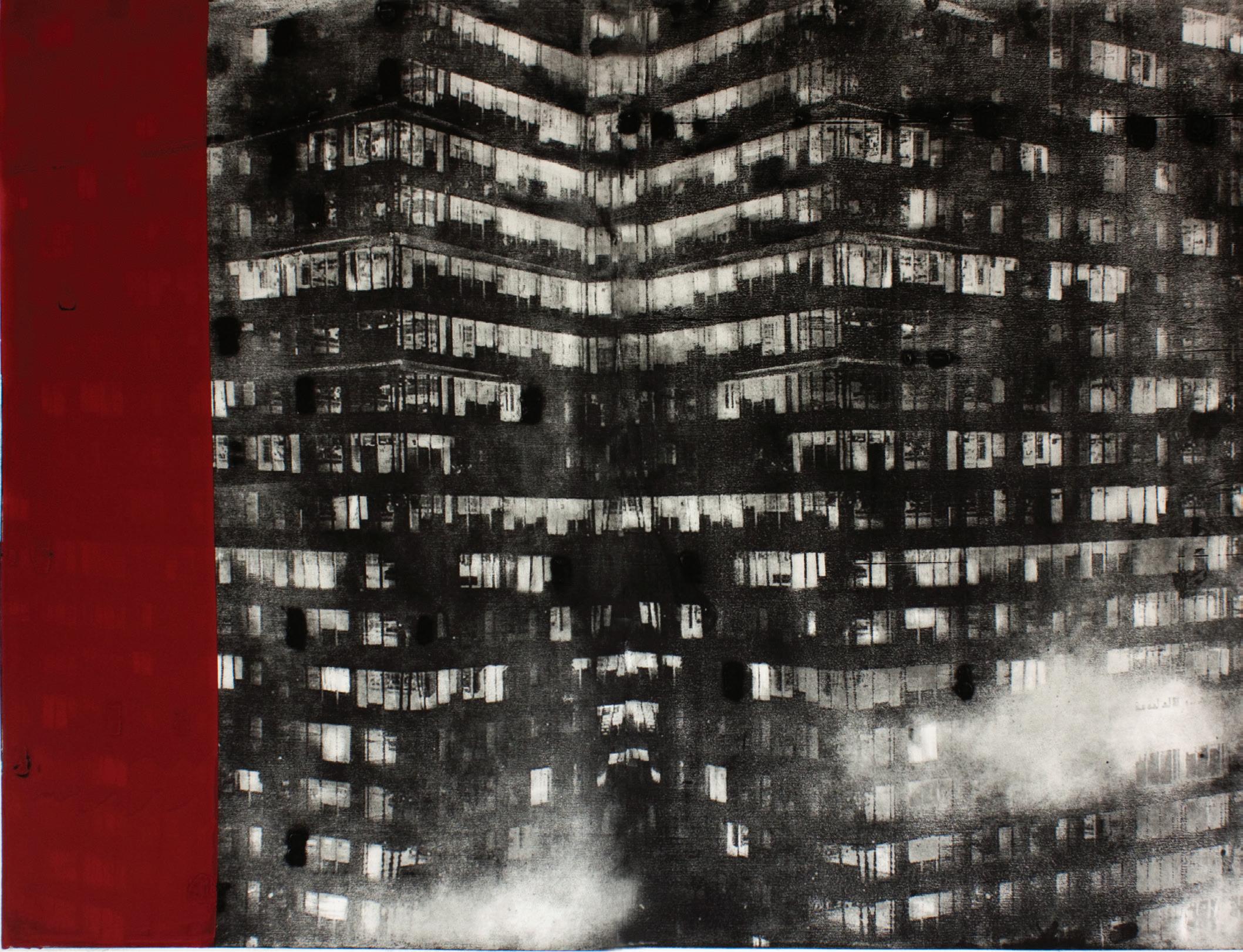

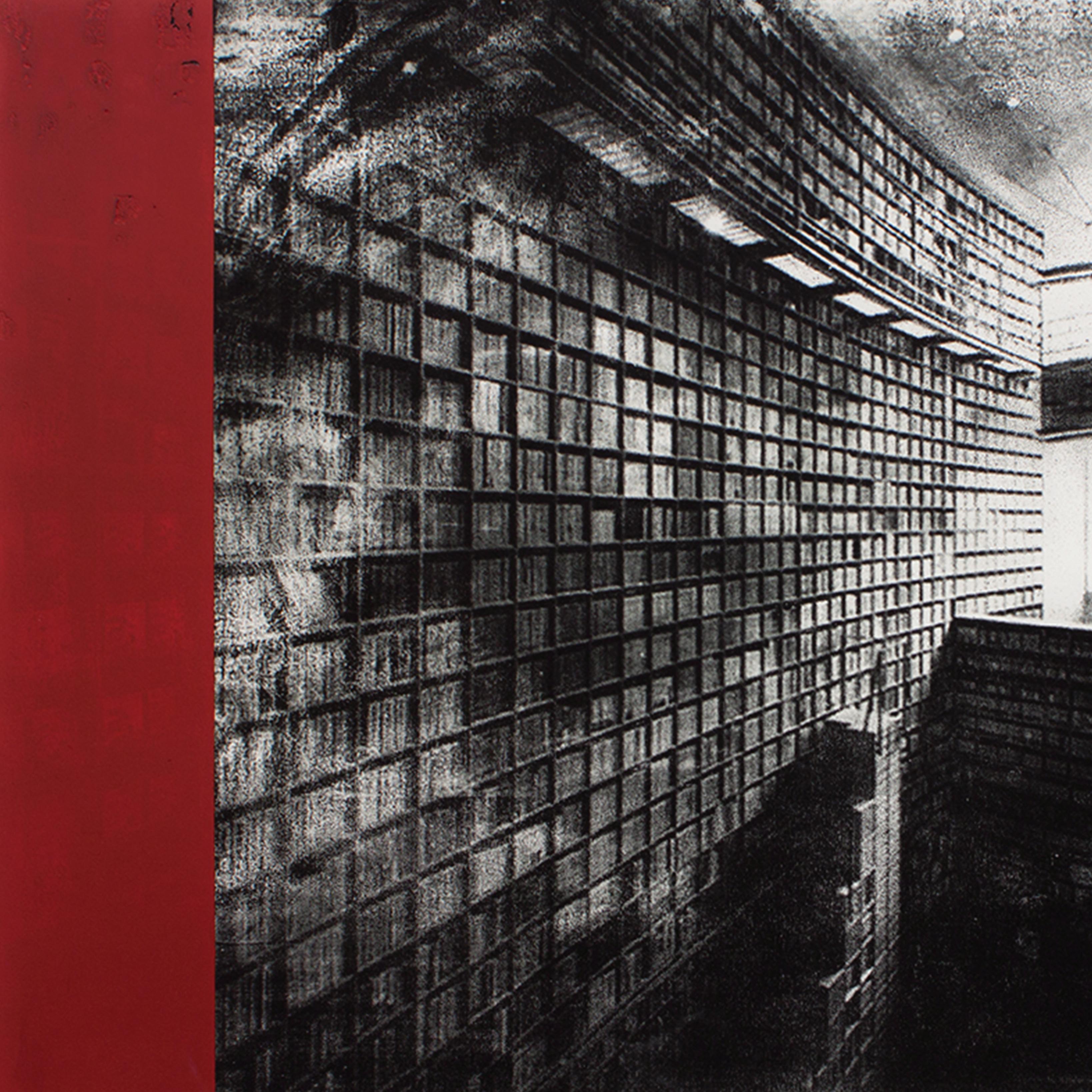

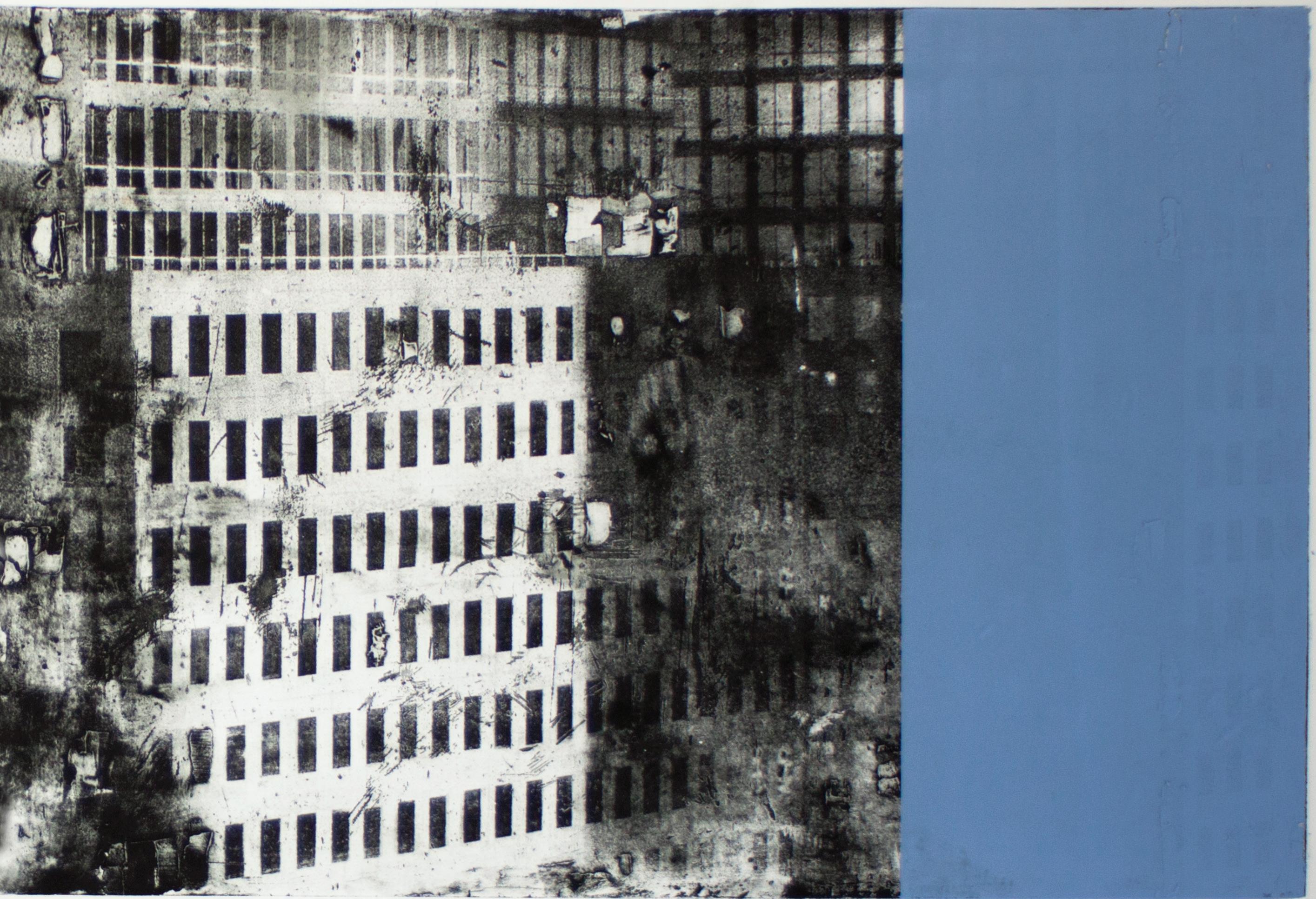

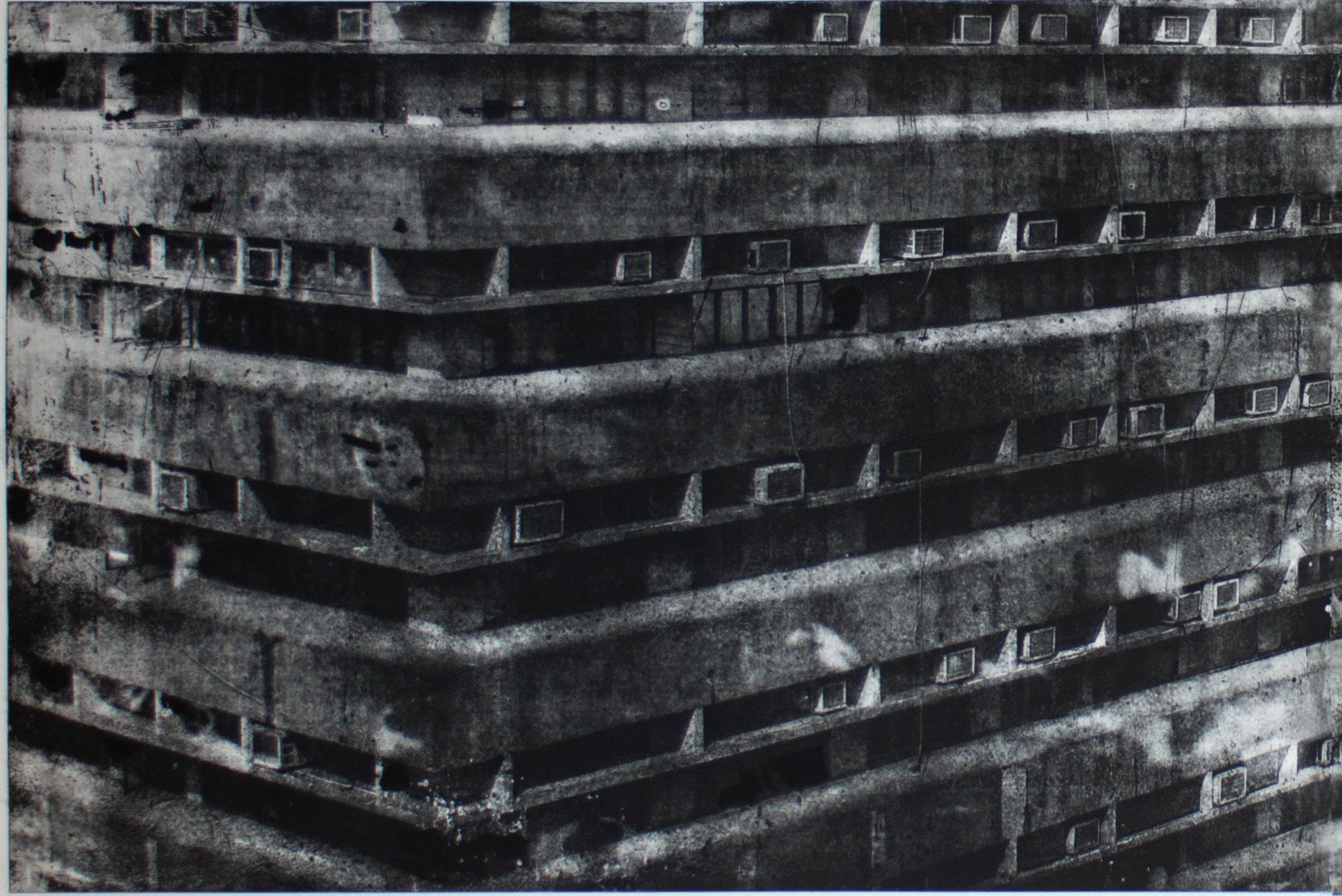

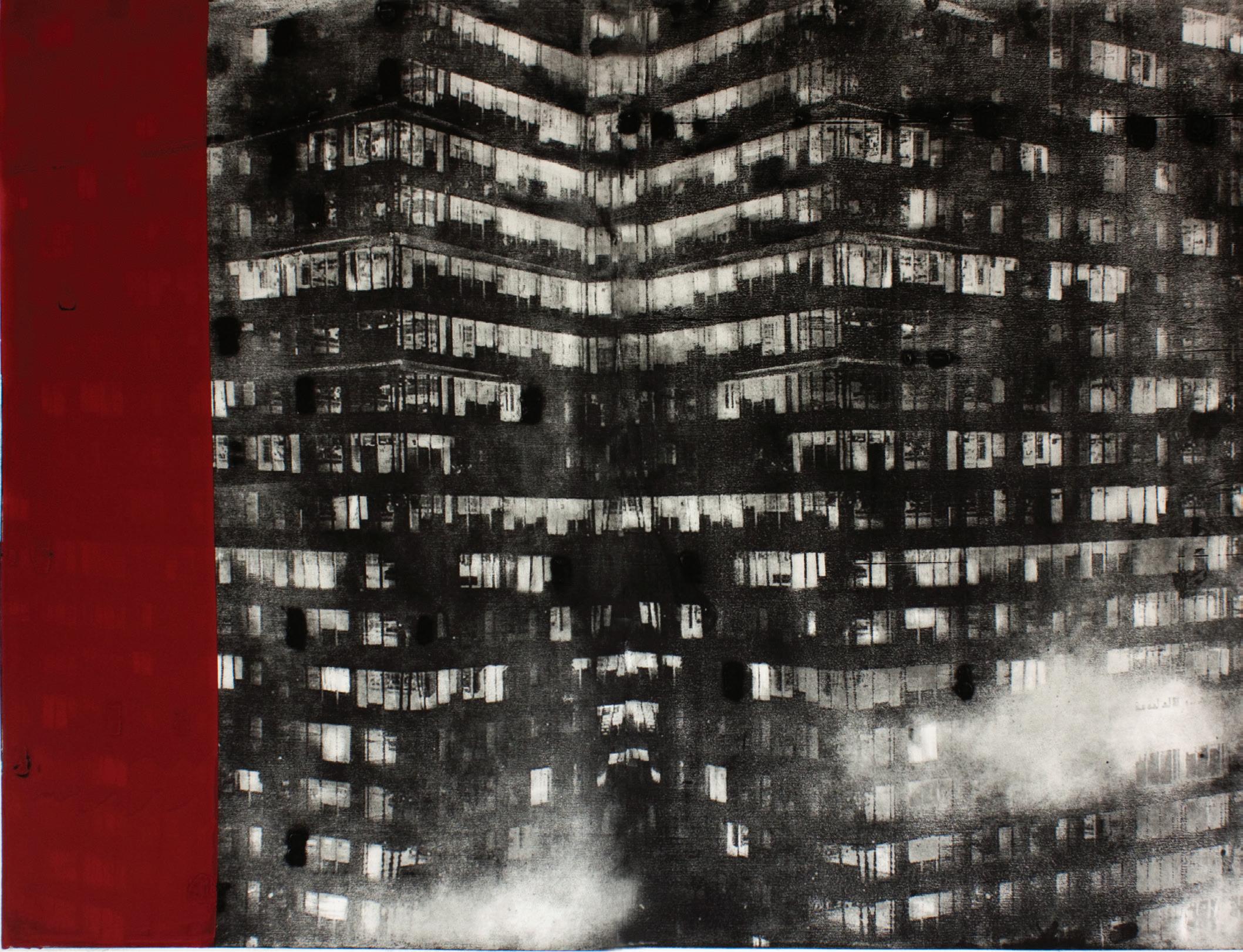

My first encounter with the print works of Ulrich J. Wolff occurred during jurying of the Okanagan Print Triennial in 2021. That year, Wolff was awarded top prize for a selection of his works. Each of those works contained tonally rich, yet stark black and white, depictions of cityscapes – closely packed apartment blocks and office buildings viewed from a slightly elevated perspective, as though viewers were looking down and across into areas of dense urban habitation. That perspective subtly exaggerated senses of depth beneath the picture plane, suggesting the building facades stretched broadly in front of the viewer and extended far back into space. The overall reference to a populace thus became even more extensive. We were presented with a view into an environment where many, many lives have been lived, where many, many narratives have unfolded.

As vast and densely compacted as the structures appeared, the images were without any evidence of human figuration.

In 2021, our world was in the midst of initial Covid-19 pandemic waves. The absence of people in Wolff’s prints seemed a poignant reference to the mandated isolation we were all being subjected to. The three prints exhibited in 2021 evoked an initial interpretation of embodied sense of loss, loneliness and isolation. They proved an effective metaphor for that particular time and the transpiring global circumstances .

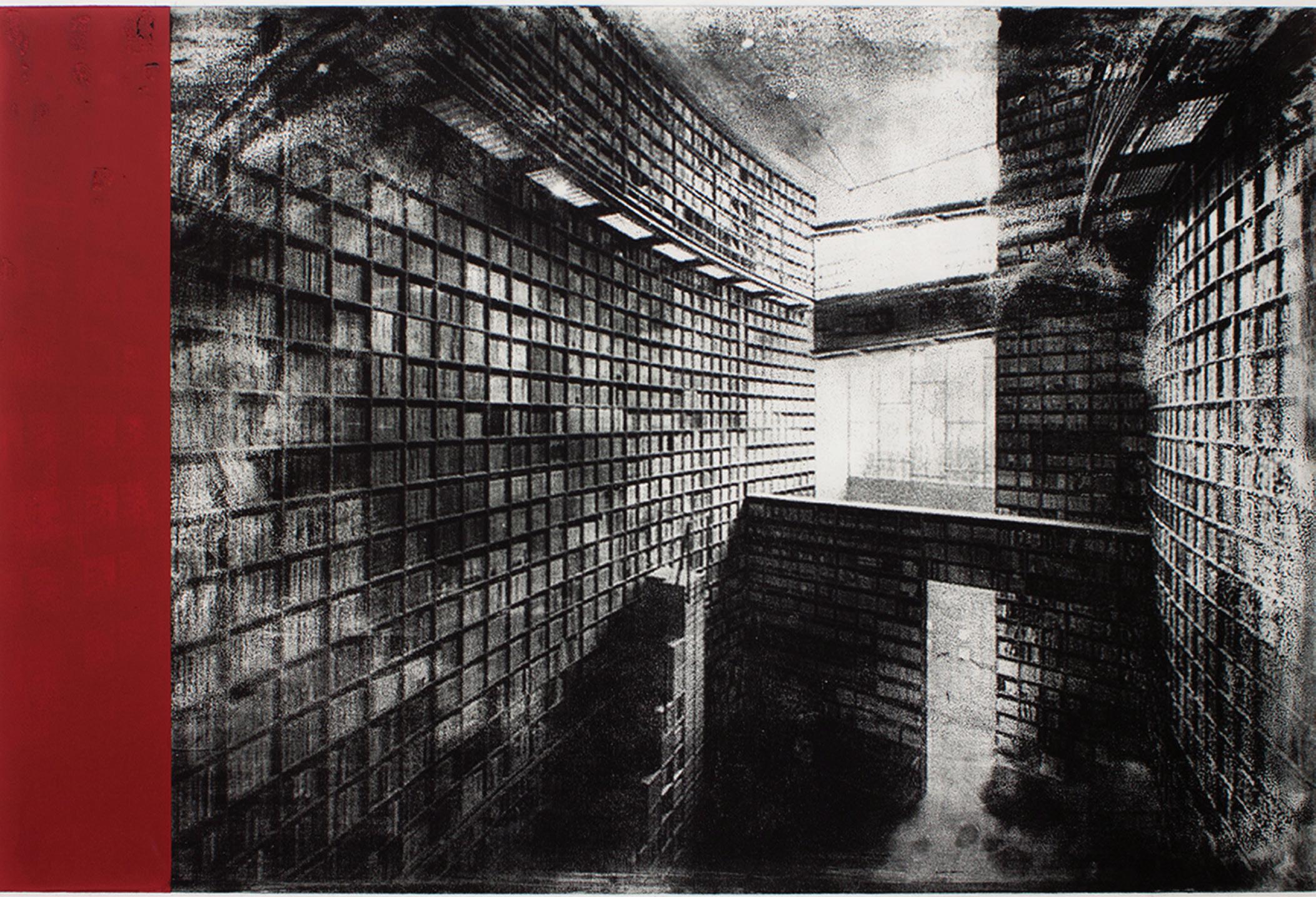

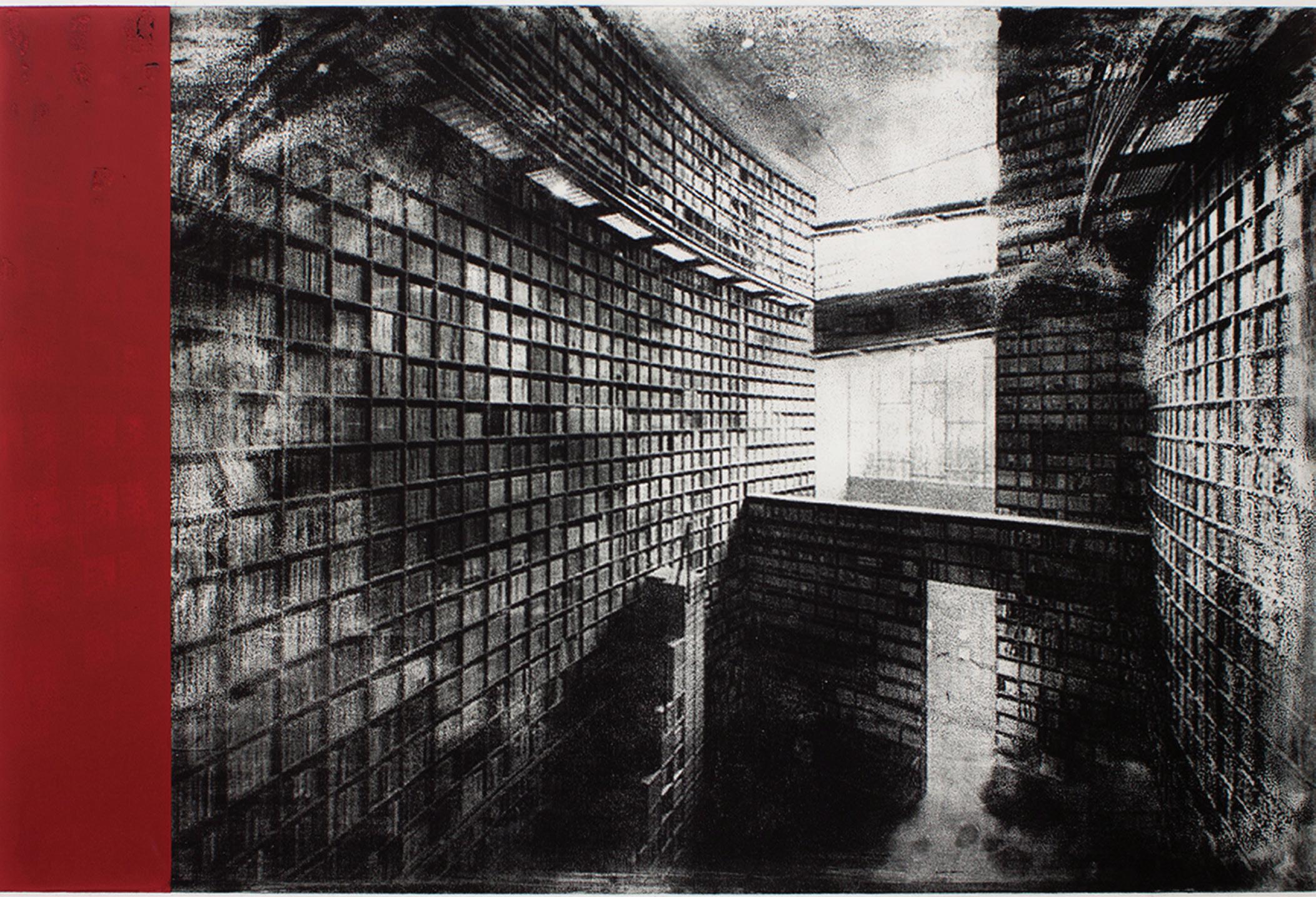

Wolff’s prints are all large in scale – large enough to fill the viewer’s field of vision and feel immersive. The prints are not, however, so large that they don’t also entice viewers into an intimate, close-up, look. Indeed, upon close scrutiny, evidence of urban decay on the surfaces of the various structures appears. Decay infuses a sense of history into the environments. This calls up Jacques Derrida’s contention that absence leaves a trace. Time and the activities of life imprint palimpsest-like evidence of human presence into the spaces of Wolff’s prints.

There are typically multiple perspectives at play in Wolff’s prints. The urban scape appears like an overlapping compilation of similar locations. Perhaps a memory of high-density urban life from a collective unconscious? The scenes appear to be hybridized, a number of different points of view reduced to a sense of specificity or depicting a single and exact location. Those equivocations enable viewers to conjure something familiar, something from our own personal experiences and memories. That in turn opens up greater connection to places where one might imagine our own histories and experiences having played out.

7

In 2021 it was easy to see Wolff’s prints as sombre, and perhaps even nihilist, visons about the future of humanity. It was difficult to view anything differently. While various strains and variants of COVID 19 have not been eradicated from our lives, the virus is certainly not as omni present as it was three years ago. We might now bring a different kind of understanding to Wolff’s works (and many of the new architecturallybased images in the exhibition Let There Be Life!). This new understanding lends itself to thoughts about more than just loss. Perhaps because humankind appears to be (just) emerging from the catastrophes of a global health crisis, the notable figurative absence in Wolff’s work might now equally evoke memories and visions of the vast possibilities of what might still be ahead of us. Renewed human activity and not exclusively the loss of it. We are now able to imagine the innumerable narratives that might have and might still unfold in any given moment in these kinds of spaces. Absence, in other words, hold a presence of potential.

In reference to the presence of absence, David Gariff (senior lecturer at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC) states, it “…is the ability to render a room without people or narrative action and yet somehow convey the sense of their being in the space – a lingering life force, as if someone has just departed or is about to arrive.”

Suggesting presence through a depiction of absence is a trope used by many artists as a means of effectively activating a viewer’s involvement within a given work.

In 1952, artist and composer John Cage created arguably his most seminal work, 4’33”. During a performance lasting exactly four-minutes and thirty-three seconds, the performer/musician sits silently at a closed piano. A listener/audience member becomes acutely aware of other sounds and stirrings in the concert hall – the buzzing of lights, the shuffling of feet, the creaks and groans of theatre seats, etc. The absence of the expected sound of a piano recital invites (possibly demands?) a listener to notice, and then pay attention to, ambient sounds in the concert hall. Many also turn their thoughts inward as they become increasingly aware of their place within that environment. Pianist David Tudor (who made the premiere performance of 4’33”) remarked that the piece was “one of the most intensive listening experiences you can have”. Like things a listener might notice while experiencing a work like 4’33”, Wolff’s urban prints have an imagined auditory quality. They suggest sounds. But the prints also call forth the actions and human industry that may have (or may still) take place in these imaginary environments. Wolff has created spaces where we can simultaneously remember and imagine.

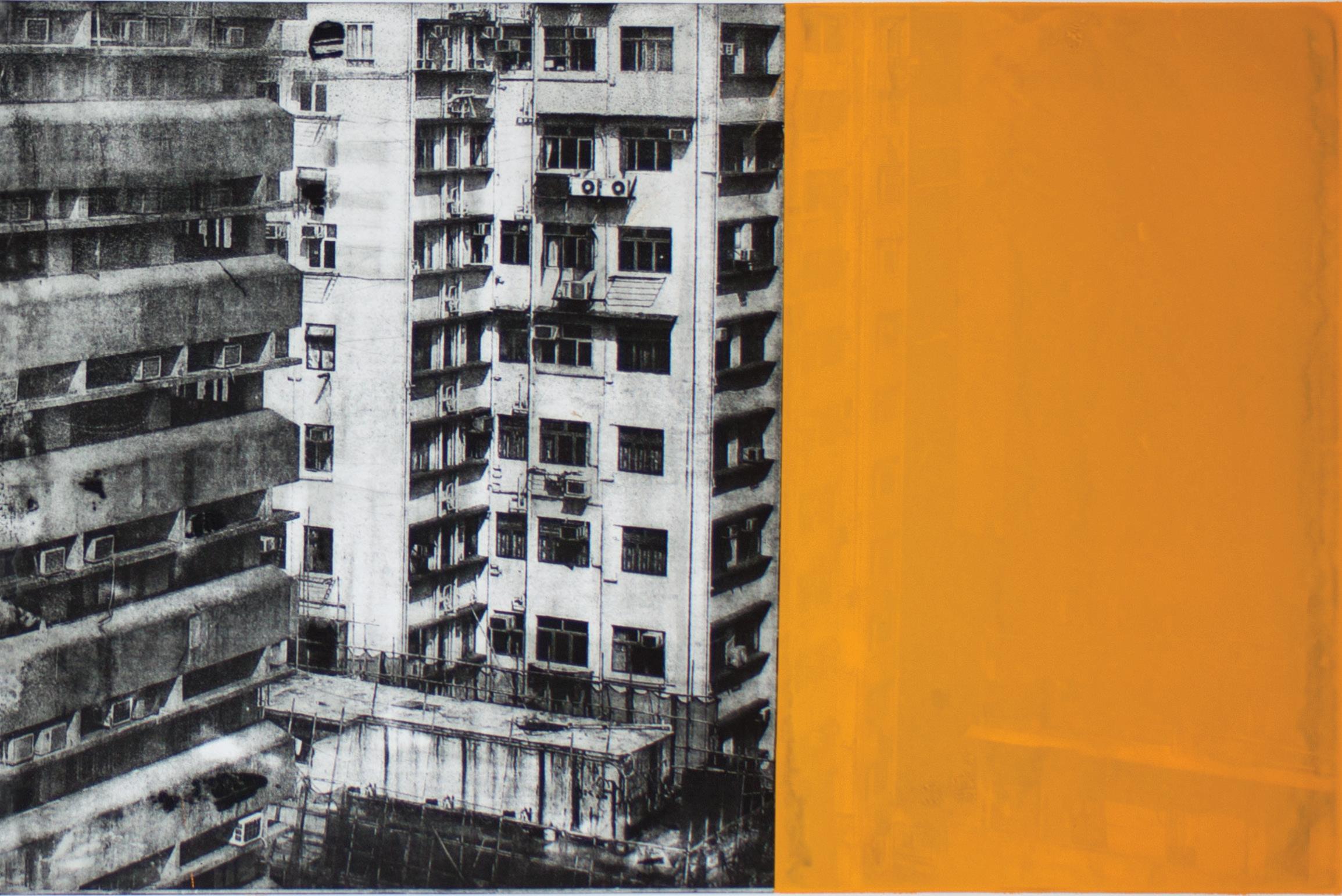

Wolff’s depictions of cityscapes are largely devoid of representational colour. Colour suggests specificity and individuality. Colour’s absence, in favor of a fairly strict and perhaps purposefully ominous monochromatic palette and a paring away of variations and intricacies of chroma, provides an opportunity for a viewer to slow down. To spend some time injecting their personal memories and experiences into each scene. We aren’t confronted with the memories or the artist’s specific references to place (or even the intention of the characters who might have once occupied these buildings). We are instead left to read into and complete

8

narratives for the works in our own ways. While colour is mostly absent from the photographic imagery, Wolff consistently places large, frontal colour bars adjacent to the perspectively oriented cityscapes. That exclamation mark of colour suggests the liveliness of life and the possibility of continued life in these spaces. Without those coloured shapes, the reading of these empty and somewhat time worn spaces might be one of finality, of something at its end.

Wolff is not providing us with a singularly pessimistic image of the world nor is he presenting a world with a false sense of optimism. I contend the colour bars in his works inject a sense of liveliness and optimism about the possibilities of future lives. But, the human absence and visual austerity could also be read as a warning of what might be to come. Whatever Wolff’s intent, the colour blocks are prompts to contemplate our place and the harmful activities we undertake within an ever-expanding populace and globally compromised environment. In that awareness, and through that contemplation, lies possibility for change and perhaps a glimmer of optimism. In his 1992 article, The Cognitive and Mimetic Function of Absence in Art, Music and Literature, Timothy Walsh states that “whenever we are confronted with a perceived absence, we typically become more intensely aware of our surroundings and more speculative in our thinking.” Walsh goes on to suggest that the “manipulation of absence and uncertainty can be productive and empowering…”

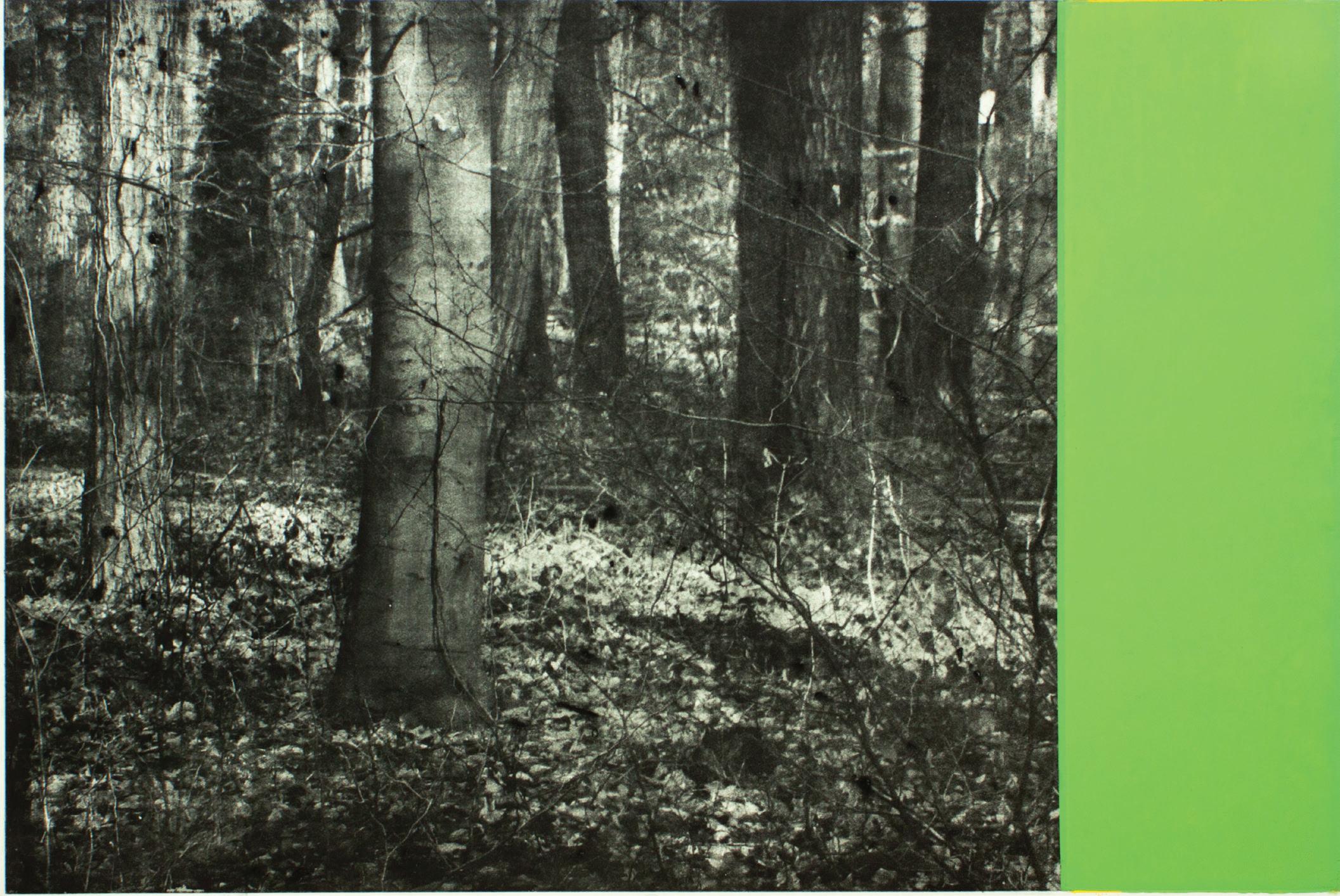

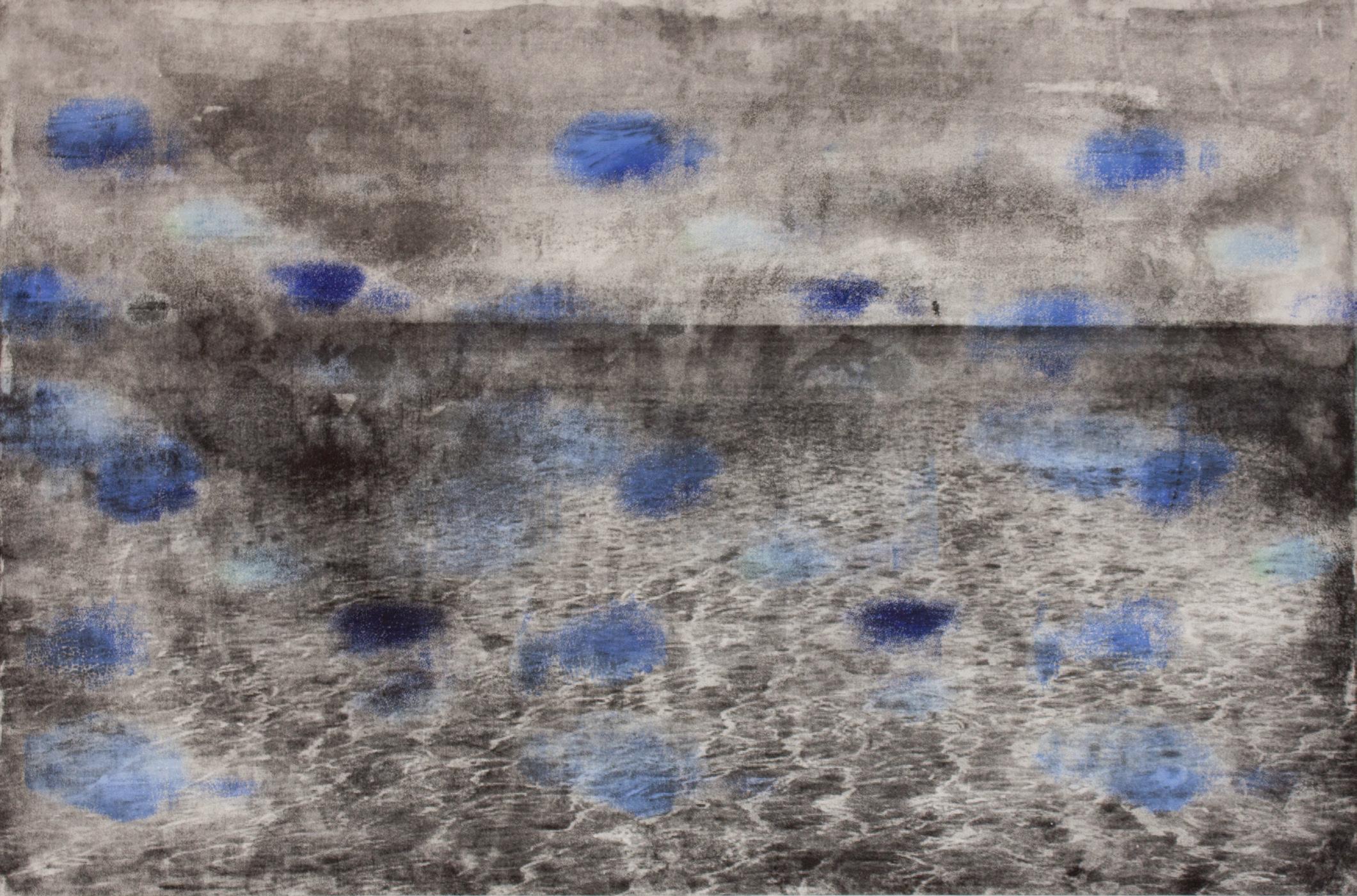

Certainly, the threat of global war, widespread famine, human health crises and isolation, and the degradation of the environment could all be subtexts in Wolff’s urban prints. But his other works –images of trees, ripples on water, fields of drooping sunflowers, clouds, and landscapes– equally portend the threats that face so much of humanity. Despite their ominous and moody palette, those images do more than just foretell impending tragedy. They depict aspects of life on the planet. Yes, that life seems threatened and sombre, but Wolff also depicts breezes on the surface of water, growth (even dead sunflowers illustrate a moment at the epitome of the harvest when the fruits of agrarian labour is at its most abundant) and the sublime magnificence of the spaces we inhabit.

Indeed, let us move forward contemplatively – there is much to lose. Let There Be Life!

Briar Craig received a BFA from Queen’s University in 1984 and an MFA in printmaking from the University of Alberta in 1987. He is a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus and has been teaching printmaking (drawing and photography) since 1987.

His work has been exhibited around the world in over twenty-five solo and over three-hundred and fifty juried group exhibitions.

He is the co-founder and co-curator for the Okanagan Print Triennial which has been running since 2009.

9

THERE MUST BE LIFE

Fotoradierungen von Ulrich J. Wolff

Dorit Schäfer

„Es muss Leben geben!“ Ein aufrüttelnder Appell im Zeitalter des Anthropozäns, in dem mehr als acht Milliarden Menschen die athmosphärischen Bedingungen für das Leben auf der Erde wesentlich bestimmen. Artensterben, Klimawandel, Umweltverschmutzung – die Menschheit steht mit Blick auf die sich rasant entwickelnden Veränderungen auf unserem kostbaren blauen Planeten vor ihrer wahrscheinlich größten Aufgabe, wenn sie weiter existieren möchte. „Ich bin Leben, das Leben will, inmitten von Leben, das leben will“ gehört zu den bekanntesten Zitaten des Mediziners, Theologen, Philosophen, Musikers und Pazifisten Albert Schweizer, der die Ehrfurcht vor dem Leben zur ethischen Leitidee seines Wirkens machte – eine zeitlose, ungeachtet jeder Religiosität gültige Leitidee und heute aktueller denn je. Und doch: Jeder Appell, Leben zu ermöglichen, trägt unweigerlich die zutiefst existenzielle Ambivalenz in sich, das Ende jeden Lebens, den Tod mitzudenken. „There must be life!“ ist daher beides: Ausdruck eines Glaubens an die Notwendigkeit des Lebens und unausgesprochenes Wissen um seine Endlichkeit.

Ulrich Wolff gibt mit diesem Titel ein Thema vor, das ein wesentlicher Auslöser, eine innere Triebfeder und ein allgegenwärtiger Beweggrund für das Schaffen von jedweder Art von Kunst ist: Die Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen Vergänglichkeit, die Vanitas , der die Menschen mit ihrer Kunst etwas entgegenzusetzen vermögen. Damit bewegt sich das Werk Wolffs bewusst in der Tradition einer klassisch-europäischen Kunstgeschichte, die er auch in seinen Motiven auf unterschiedlichste Weise rezipiert: Stadtansichten und Architekturdarstellungen, Porträts, unterschiedliche Landschaften (Wälder, Gebirgspanoramen und Seestücke) sowie Baum- oder stilllebenartige Blumenstudien, das Themenspektrum ist vielfältig und umfasst zahlreiche Gattungen. In den letzten Jahren hat sich der ausgewiesene Experte für Radiertechniken, der über 30 Jahre lang die Druckwerkstätten der Staatlichen Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe leitete, auf die Fotoradierung konzentriert, die er vielfach mit farbigen Siebdruckflächen kombiniert. Die fotografischen Vorlagen stammen aus eigener Produktion oder aus dem Internet, werden digital verändert, teils collageartig neu zusammengesetzt und auf der Druckplatte weiterbearbeitet. Im Abdruck stets schwarz-weiß, erzeugen Wolffs Überarbeitungen die ästhetische Wirkung von historischen Aufnahmen, von verstrichener Zeit, in der die abgelichteten Bilder verwitterten: Kratzer und Abnutzungsspuren lassen die Formen verschwimmen, diffuse Flecken und dunstige Schwaden durchziehen Landschaften, Hochhäuser oder Gesichter. Die Motive erhalten eine ungewisse Historizität und scheinen Dokumentationen einer so nicht mehr vorhandenen Landschaft, Natur oder Architektur zu sein.

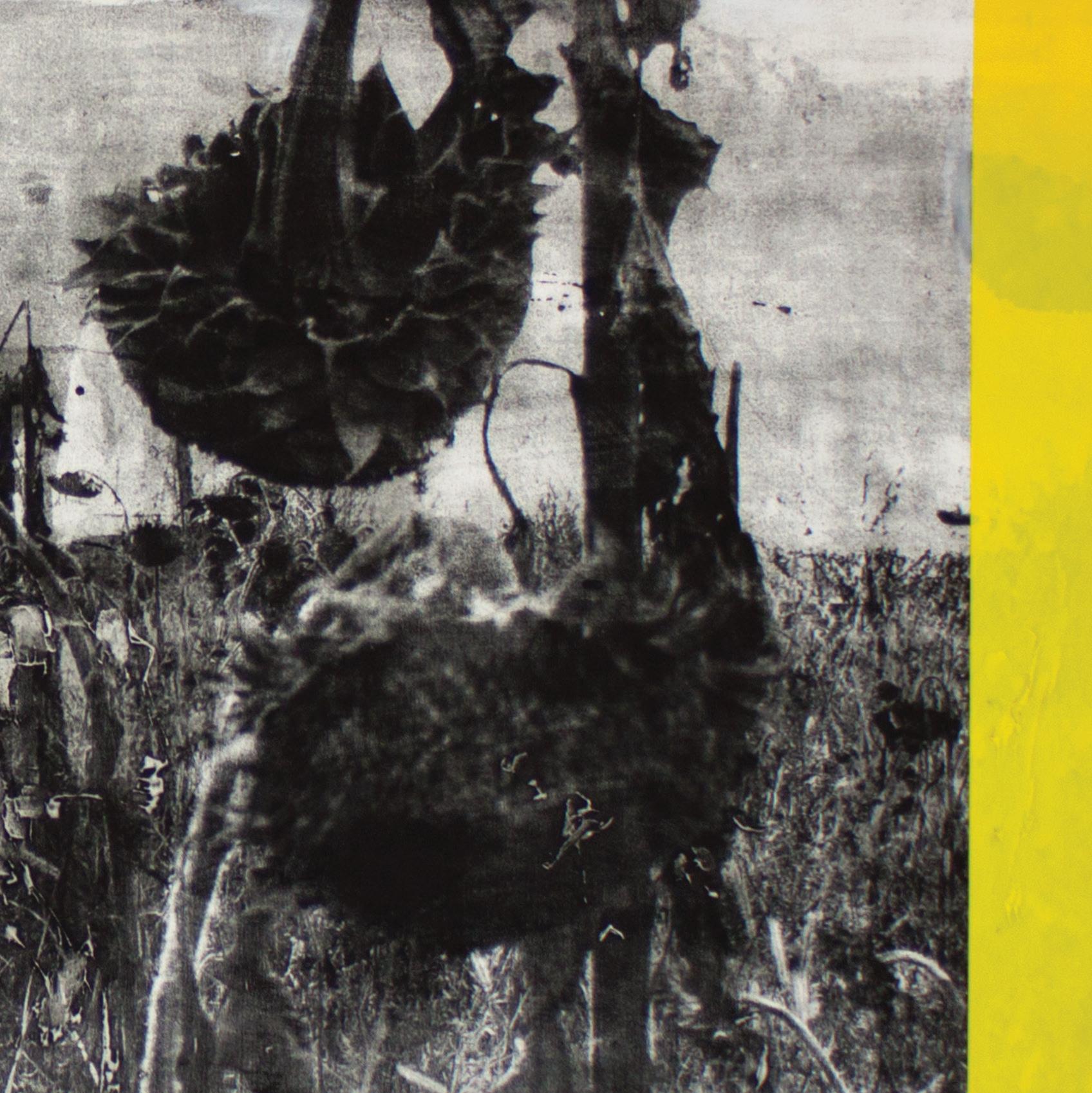

Ein Motiv, das die Endlichkeit alles Lebens besonders deutlich vor Augen führt, ist das Bild eines Sonnenblumenfeldes im Spätsommer: Im dunklen Vordergrund neigen sich die schweren, verwelkten

10

Blütenköpfe an geknickten Stielen zu Boden – Symbole für das Untergehen der Sonne, für die Hinfälligkeit von Schönheit und für die Sterblichkeit prallen Lebens. Denn im Blick auf die verblühten Pflanzen entstehen in der Imagination der Betrachtenden andere Bilder – Bilder leuchtend gelber, vitaler Blumen, die ihre Köpfe der Sonne entgegenstrecken und Sinnbilder für Licht und Leben sind. In der europäischen Kunst wecken Sonnenblumen zudem immer Assoziationen mit Gemälden van Goghs, der sich im Sommer 1888, während er im südfranzösischen Arles auf seinen Künstlerfreund Paul Gauguin wartete, malerisch mit großer Leidenschaft diesen Blumen widmete. An seinen Bruder Theo schrieb er: „Ich male jetzt mit demselben wütenden Eifer, mit dem ein Marseiller seine Bouillabaisse verzehrt; das wird Dich nicht wundern, wenn Du hörst, dass ich große Sonnenblumen male. […] Wenn ich also diesen Plan ausführe, wird es ein Dutzend Bilder geben. Das Ganze eine Symphonie in Blau und Gelb. Ich arbeite jeden Morgen von Sonnenaufgang an. Denn die Blumen verwelken schnell, und das Ganze muss in einem Zug gemalt werden.“ Heute gehören diese Gemälde van Goghs zu den berühmtesten und teuersten der Welt. Es erstaunt daher nicht, dass im Jahr 2022 ausgerechnet eines seiner Sonnenblumenbilder von Klimaaktivistinnen in der Londoner National Gallery attackiert wurde. Van Goghs Sonnenblumen wurden als Sinnbild für das gefährdete Leben auf diesem Planeten gesehen, das den Protestierenden zufolge der Gesellschaft auf einem Gemälde mehr wert ist als in der bedrohten Natur. Auf Ulrich Wolffs Radierung, deren breites Querformat die weite Ausdehnung des Sonnenblumenackers suggeriert, ist das hinzugefügte gelbe Farbfeld ein deutlicher Hinweis auf die ursprüngliche Leuchtkraft der flammenden Blüten, für die lebensspendende Kraft der Sonne und für eine „Symphonie in Blau und Gelb“, wie van Gogh sie beschrieb und sie in unserer Vorstellungskraft entsteht.

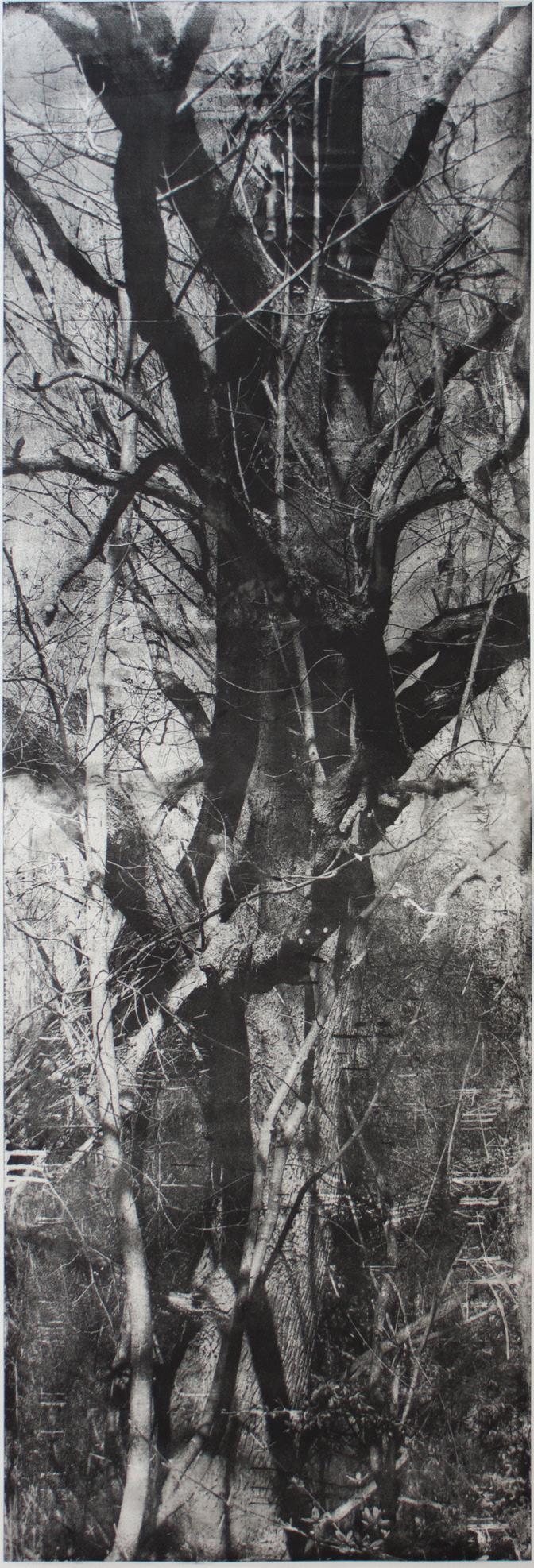

Blicke in dicht bewachsene Wälder sowie einzelne knorrige Eichen, die ihre Zweige wie taumelnde Krakenarme in die Luft strecken, gehören zu Wolffs weiteren Naturmotiven, mit denen seine Kunst tief in der europäischen Landschaftsmalerei verwurzelt ist. Von der Donauschule über die arkadischen Landschaften des 17. Jahrhunderts und den bizarren Eichensilhouetten Caspar David Friedrichs bis zur Schule von Barbizon – die künstlerische Faszination für Bäume korreliert mit den Mythen, die sich um diese großen und alten Organismen weit über Europa hinaus in nahezu allen Kulturen der Welt gebildet haben. In der Antike galten Wälder als heilige Sitze von Gottheiten, wobei Eichen im Speziellen mit dem Göttervater Zeus verbunden wurden. Im Alten Testament waren die Verlockungen der Früchte vom Baum der Erkenntnis im Garten Eden Auslöser für die Selbstermächtigung des Menschen und für sein sündhaftes Verlassen aus göttlicher Obhut. In der nordischen Mythologie verkörpert die Esche Yggdrasil als Weltenbaum den gesamten Kosmos, unter alten Linden wurde über Jahrhunderte hinweg Gericht gehalten, und Buddha fand unter einer Pappel-Feige Erleuchtung. Noch heute wird häufig zur Geburt eines Kindes ein Baum gepflanzt, und „Stammbäume“ werden für die Genealogien von Familien aufgeschrieben. So selbstverständlich Bäume zum Leben der Menschen gehören und so sehr sich die Menschheit global mit ihnen identifiziert, so rücksichtslos werden sie jedoch als Rohstoff genutzt und gnadenlos abgeholzt. Die zivilisatorische Ausbeutung hat bedrohliche Ausmaße erreicht, und der Klimawandel unterstützt diese Entwicklung auf erschreckende Weise. Brennende Wälder weit über das natürliche Maß hinaus gehören mittlerweile auf allen Kontinenten zu einem gängigen Bild und verwüsten weite Landstriche. Vor diesem Hintergrund inszeniert Ulrich Wolff die Bäume und Wälder auf seinen bearbeiteten Fotoradierungen wie Naturaufnahmen aus einer weit

11

entfernten Vergangenheit. Die gestürzten Zweige, schlingernden Äste und dichten Wälder scheinen hinter wabernden, teils schwefelgelben Nebeln zu verschwimmen. Die Fragilität Ihrer Schönheit, die Verletzlichkeit ihrer Würde ist hinter den bedrohlichen Schleiern umso deutlicher wahrnehmbar. Bewusst verzichtet der Künstler in seinen Naturdarstellungen auf die Darstellung des Menschen, dessen Anwesenheit auch in den landwirtschaftlich genutzten Äckern von Sonnenblumen oder Maispflanzen lediglich implizit vorhanden ist. Wolffs Naturdarstellungen zeigen deutliche Bezüge zu den interdisziplinären Ansätzen des Ecocriticism und der Environmental Humanities, die sich zunächst in der Literaturwissenschaft etablierten und in den letzten Jahren zum kulturwissenschaftlichen Forschungsfeld der Plant Studies führte. Vor dem Hintergrund der wachsenden Gefährdung globaler Ökosysteme konzentriert sich diese Forschungsrichtung auf die Wechselwirkungen von Mensch und Natur und betrachtet kritisch die durch eine zunehmende Trennung beider Bereiche entstandene Abwertung der natürlichen Umwelt durch den Menschen. Dabei ist die lebensspendende Bedeutung der Phytossphäre auf der Erde unumstritten: Die Bedeutung der Pflanzen in Kunst und Kultur ist zurückzuführen auf ihre Bedeutung als existenzielle Sauerstoff- und Nahrungslieferanten, als Grundbedingung des menschlichen Lebens. Angesichts dieser globalen Situation plädiert der Biologe und Philosoph Andreas Weber für ein neu gedachtes Zusammenspiel von Natur, Mensch und Ökonomie und führt die Denk-Kategorie des Enlivenment ein: Die Lebendigkeit als Form einer Teilhabe, in der sich der Mensch über seine fundamentale Zusammengehörigkeit mit der Natur bewusst ist, die er zwar beeinflussen, von der er sich jedoch nicht lösen kann. Die Erkenntnis, dass wir nicht „über“ der Natur stehen, sondern uns als Teil von ihr begreifen müssen, führte die amerikanische Philosophin und Wissenschaftshistorikerin Donna Haraway bereits vor über zwanzig Jahren zum Begriff der natureculture.

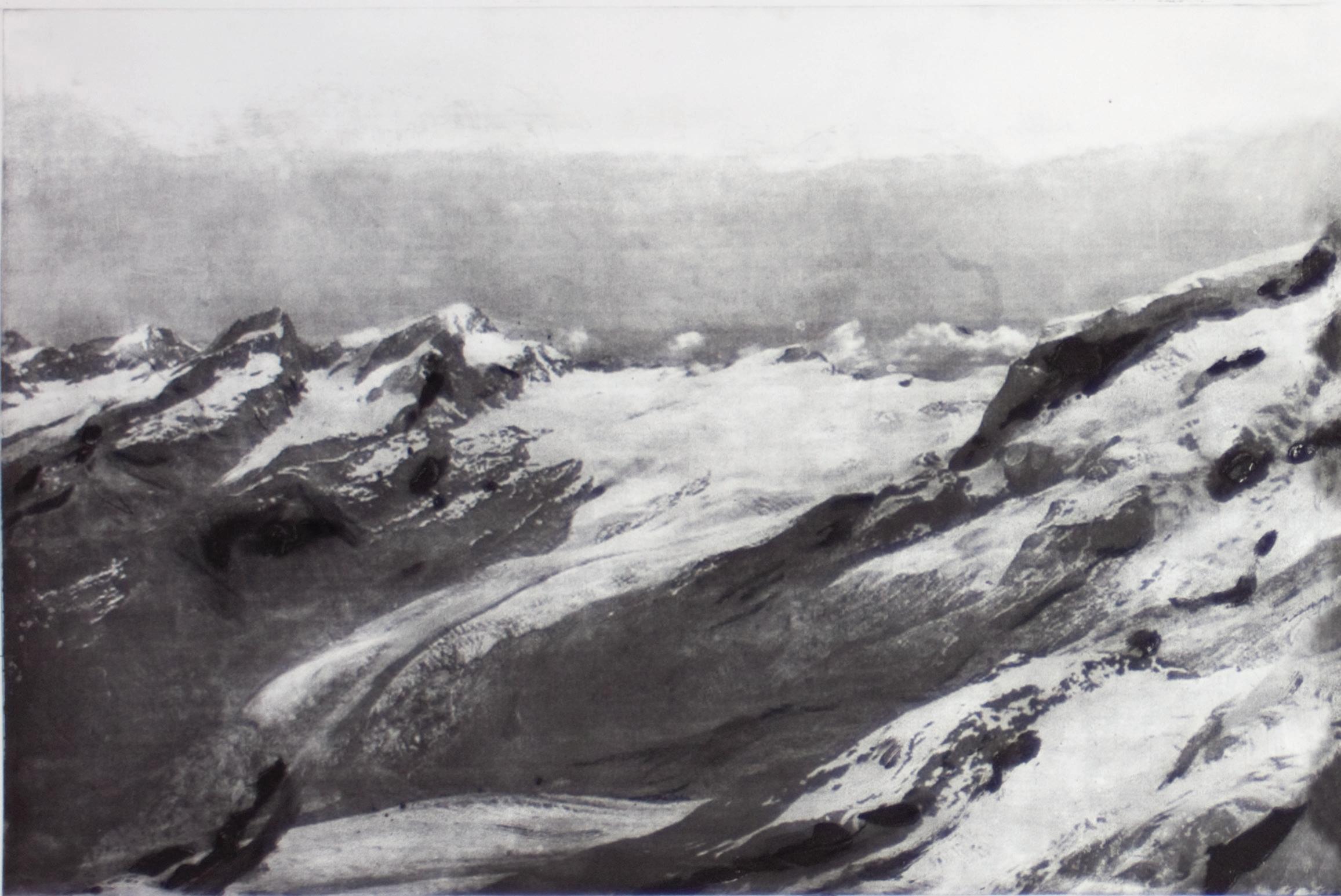

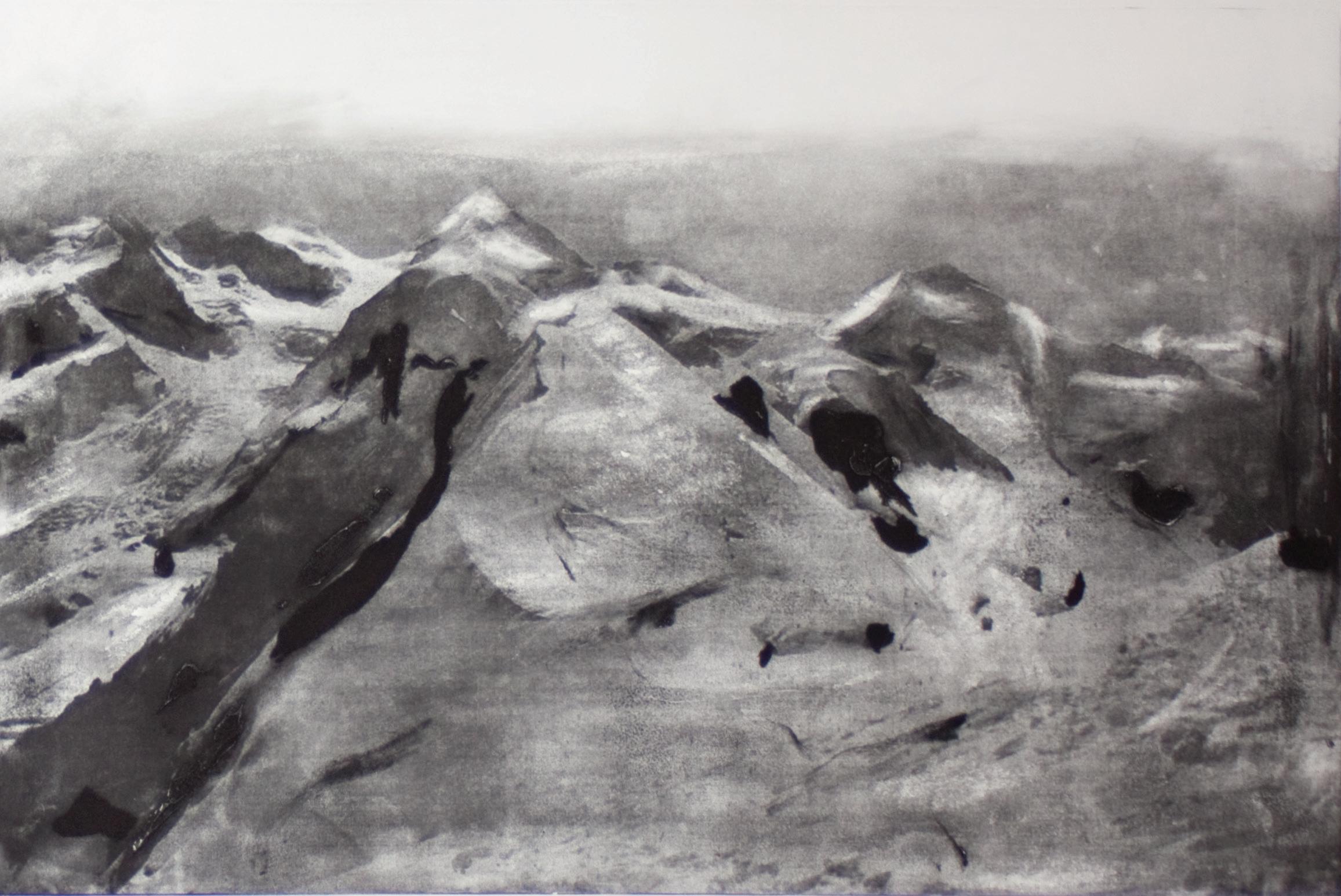

Dass die Natur auch gut ohne den Menschen denkbar ist, zeigen Wolffs oft im großen Querformat komponierte Gebirgslandschaften oder Seestücke. Der Künstler lehnt sich in diesen Bildern eng an die Romantik des 19. Jahrhunderts an. Die Motive einer überwältigenden, erhabenen und scheinbar zeitlosen Natur reduzieren die Bedeutung des Menschen auf eine Weise, die auch als schmerzlich empfunden werden kann. Auf panoramaartig komponierten Darstellungen werden die unbegrenzten Weiten schneebedeckter Berge oder uferloser Meereshorizonte abrupt von den Bildrändern beschnitten, ohne dass rahmende Elemente den Blick behutsam in die Tiefe führen könnten. Diese radikalen Beschnitte suggerieren eine sich über den gezeigten Ausschnitt erstreckende, unbekannte Landschaft, die sich der eingeschränkten menschlichen Wahrnehmung entzieht. In der Landschaftsmalerei wurde eine ähnliche Entgrenzung erstmals von Caspar David Friedrich 1810 in seinem Gemälde „Der Mönch am Meer“ (heute in der Alten Nationalgalerie in Berlin) dargestellt, mit dem er kompromisslos gegen die traditionellen Konventionen verstieß. Ein berühmtes Zitat von Heinrich von Kleist fasst die damalige Erschütterung vor diesem als radikal empfundenen Gemälde zusammen, dessen Uferlosigkeit den Eindruck erzeugte, „als ob Einem die Augenlider weggeschnitten wären“.

Vergleichbare Erfahrungen von Grenzenlosigkeit entstehen beim Betrachten von Wolffs Stadtlandschaften aus nicht lokalisierten Mega Cities. Riesige Wohnmaschinen erstrecken sich ähnlich unbarmherzig über

12

die Bildränder hinweg, nur können sie nicht mit der Erhabenheit der Natur aufwarten. Der Mensch erschafft sich selbst unmenschliche Behausungen von überdimensionierter Größenordnung, in der er zu verschwinden droht. Die Radierungen, durch die Bearbeitungen des Künstlers in ihrer Wirkung teils noch gesteigert, beeindrucken durch ihre Darstellungen einer bedrückenden Anonymität, in der dunkle Straßenschluchten unsere Blicke verschlucken und uns schwindeln lassen. Lediglich einige erleuchtete Fenster zeugen von Wärme, Licht und Leben, doch die Bewohner treten nicht in Erscheinung. Die Hybris aus der biblischen Geschichte des Turmbaus zu Babel liegt als kultureller Topos dieser Motive nicht fern –umso mehr, wenn man an reale menschenleere Geisterstädte denkt, die in einigen Teilen unserer heutigen Welt aus Profitstreben entstanden und schon wieder gesprengt werden. Wolffs kalkulierte Kompositionen, Collagen und Beschnitte der architektonischen Motive erzeugen jedoch eine abstrakte Formensprache, die bar jeder inhaltlichen Aussage auch eine bildnerische Schönheit vermittelt – in Anlehnung an eine Aussage der kanadisch-amerikanischen Künstlerin Agnes Martin von 1989: „Wenn ich an Kunst denke, denke ich an Schönheit. Schönheit ist das Geheimnis des Lebens. Sie liegt nicht im Auge, sie liegt im Inneren. In unserem Inneren gibt es Erkenntnis von Vollkommenheit.“

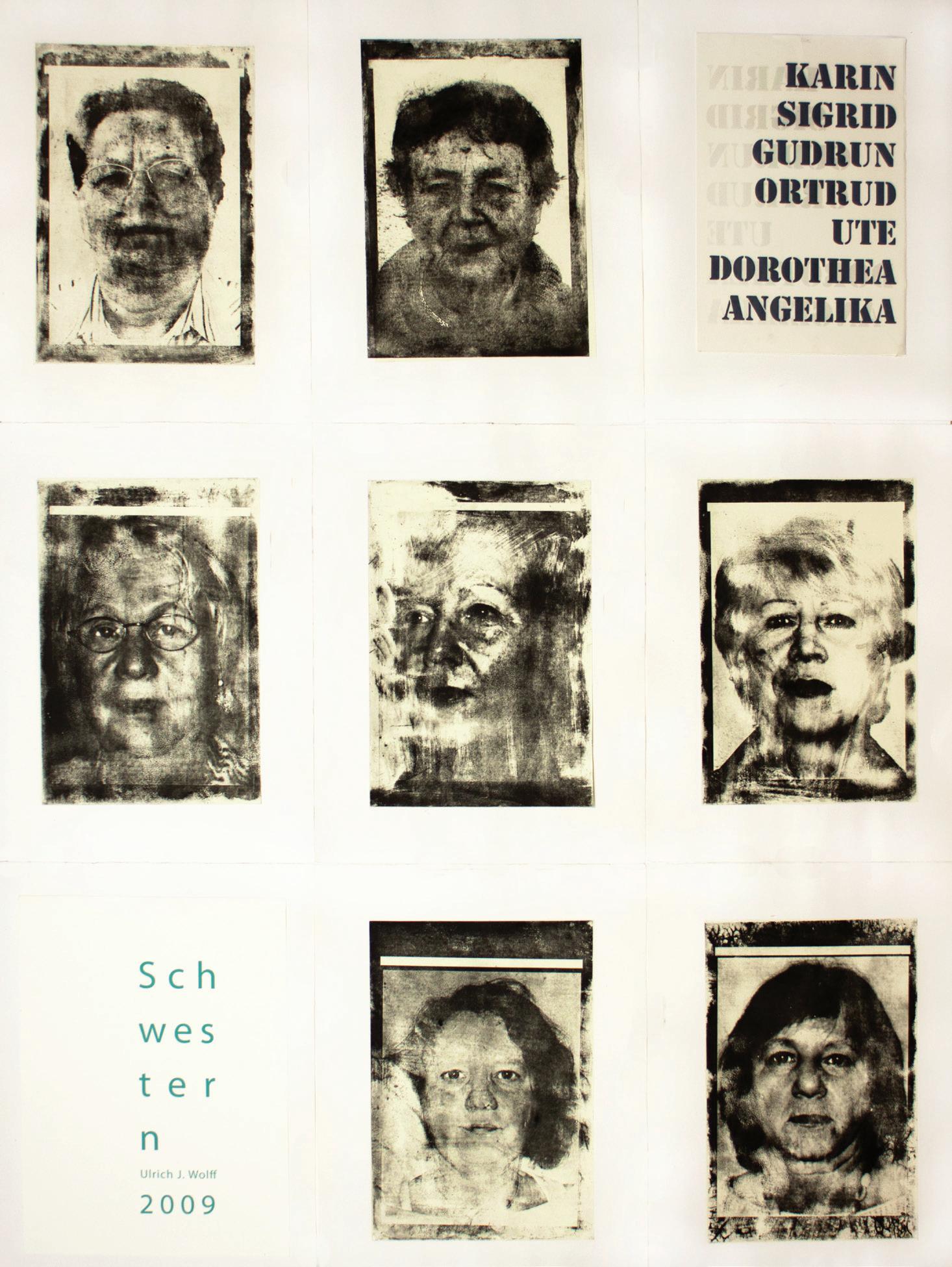

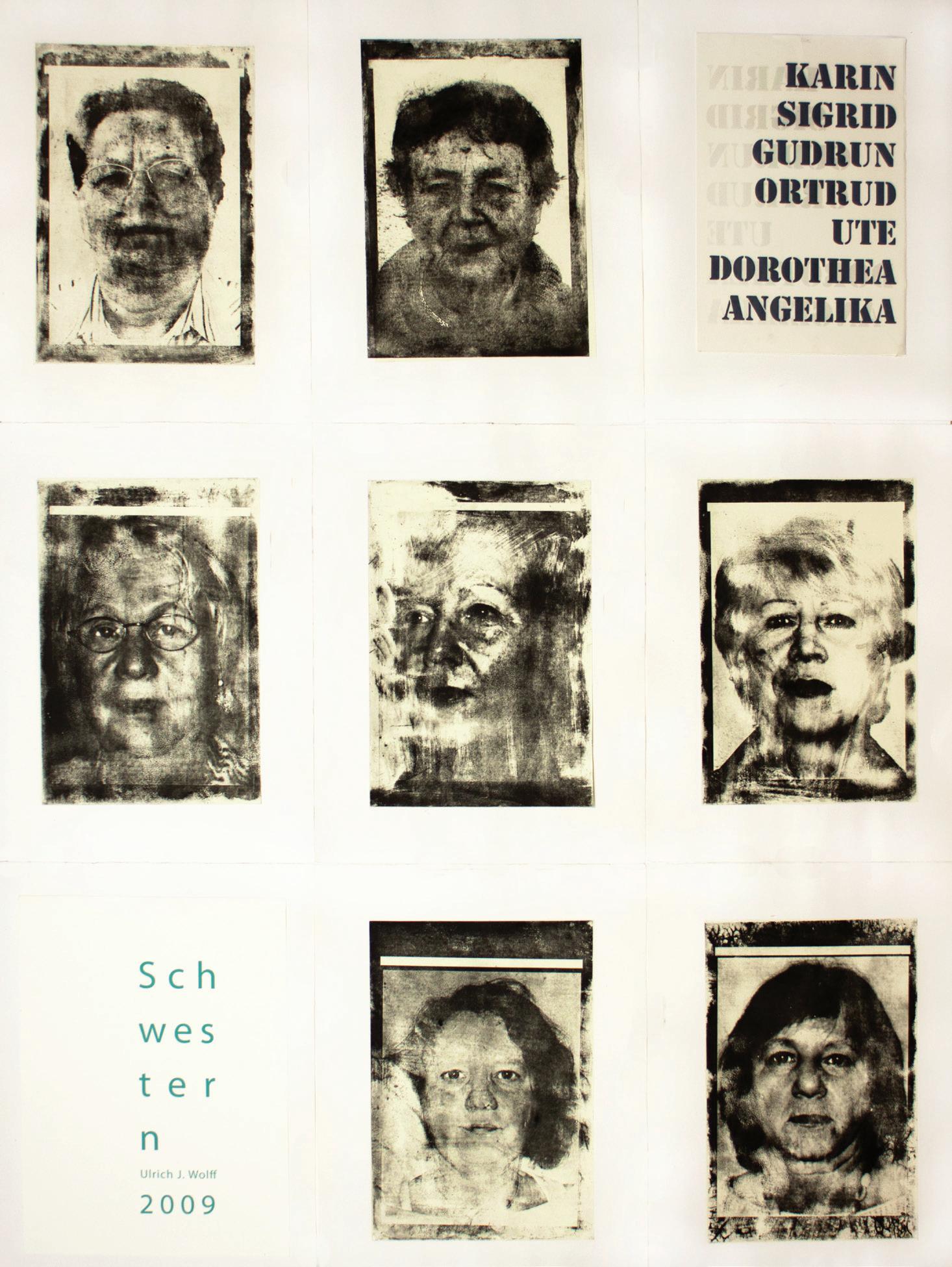

Während Wolff in seinen Stadt- und Naturlandschaften auf die Darstellung von Menschen verzichtet, zeigt er sich in seinen Porträts als uneingeschränkter Humanist. Er konzentriert sich auf einzelne Gesichter, deren Verletzlichkeit er durch eine starke Nahsicht eindrücklich veranschaulicht. In den Serien „Sieben Schwestern“ oder „Opfer/Täter“, aber auch in Einzelbildnissen außerhalb eines Kontextes sind es die Menschen als Individuen, die ihn interessieren. Durch ihre Vergrößerung verschwimmen die Umrisse und verlieren sich die Details, wobei Wolffs Bearbeitung der Negative und Druckplatten auch hier eine unbestimmte Vergangenheit suggeriert. Die Formen der Personen lösen sich auf wie unsere verblassenden Erinnerungen an sie, wie verwehende Spuren des Lebens, des Verfalls, des Erlöschens. Und doch: Es bleiben die intensiven Blicke der Porträtierten aus dem Bild heraus auf uns, die sie anschauen – eindringliche Appelle an das Leben, an seine Würde, seine Schönheit und seine Kostbarkeit, ungeachtet aller zeitlicher Begrenztheit: „There must be life!“

Dr. Dorit Schäfer studierte Kunstgeschichte, Klassische Archäologie und Französische Literatur in Heidelberg und London. 1998 wurde sie an der Universität Heidelberg mit einer Arbeit zum Thema Der Ortenberger Altar – Untersuchungen zur mittelrheinischen Kunst uns Maltechnik um 1400 promoviert. Seit 1998 ist sie als Kuratorin an der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Karlsruhe tätig, wo sie 2003 die Leitung des Kupferstichkabinetts übernahm und zahlreiche Ausstellungen zu Themen von der mittelalterlichen Kunst bis zur Moderne kuratierte. Ihre Arbeitsschwerpunkte liegen in der Zeichnung und Druckgrafik der Altdeutschen Meister, der französischen Kunst des 18.-20. Jahrhunderts und in der zeitgenössischen Zeichnung und Druckgrafik.

13

THERE MUST BE LIFE

On Ulrich J. Wolff‘s Photographic Etchings

by Dorit Schäfer

“There must be life!” A rousing plea in the Anthropocene, when more than eight billion people are decisively influencing the atmospheric conditions of life on earth. The extinction of species, climate change, pollution—given the rapidly developing changes on our precious blue planet, humanity is probably facing its greatest challenge if it wants to continue to exist. “I am life that wants life, in the midst of life that wants to live,” is one of the best-known quotations by the doctor, theologian, philosopher, musician, and pacifist Albert Schweitzer, for whom reverence for life became the ethical guiding principle of his work—a timeless, valid principle, regardless of any religious affiliation, and today more timely than ever. And yet: every appeal to enable life is inherently deeply ambivalent because the end of every life, death, must also always be considered as well. “There must be life!” is therefore both: an expression of the belief in the necessity of life and the implied knowledge that life is finite.

With this title, Ulrich Wolff sets a topic that is an important trigger, an inner mainspring and the omnipresent motivation for the creation of every kind of art: an engagement with one’s own transience, the vanitas which humans are capable of countering with their art. Thus Wolff places his work intentionally in the tradition of classic European art history, which is also reflected in various ways in his choice of motifs: city views and depictions of architecture, portraits, various landscapes (woods, mountain panoramas, and seascapes) as well as trees or still lives of flowers; the range of themes is diverse and comprises numerous genres. In recent years, Wolff, an expert in etching techniques who for more than 30 years directed the printing workshops at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe, has been focusing on photographic etchings, which he often combines with colored silk screen prints. The photographic models are either of his own making or are sourced from the internet, then digitally processed, sometimes newly combined in a collage-like manner, and further modified on the printing plate. The prints, always black and white, produce the aesthetic effect of historical photographs, of time passed, with weathered images: scratches and misty cloud landscapes, high-rises and faces, and blur the shapes. The motifs are marked by a vague historicity and seem to be documentations of a landscape, nature, or architecture that no longer exist in quite this way.

One motif that demonstrates the finiteness of all life especially clearly is the picture of a field of sunflowers in later summer: in the dark foreground, the heavy, wilted flowers bend down on broken stems—symbols for the descending sun, for the fleeting nature of beauty, and for the mortality of all life. Gazing at the withered plants brings to beholders’ imagination other images—images of brightly yellow, vital flowers that direct their heads towards the sun and are symbols of light and life. Moreover, in European art sunflowers are always associated with the paintings of van Gogh, who in the summer of 1888, while waiting in Arles in southern France for his artist friend Paul Gaugin, devoted himself with great passion to painting them. He

14

wrote to his brother Theo: “I’m painting with the same gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won’t surprise you when it’s a question of painting large sunflowers. […] Well, if I carry out this plan there’ll be a dozen or so panels. The whole thing will therefore be a symphony in blue and yellow. I work on it all these mornings, from sunrise. Because the flowers wilt quickly and it’s a matter of doing the whole thing in one go.” Today, these paintings by van Gogh are among the most famous and expensive in the world. It is therefore hardly surprising that of all things, one of these sunflower paintings was attacked in 2022 by climate activists in the London National Gallery. Van Gogh’s sunflowers were regarded as a symbol for the endangered life on this planet, which according to the protesters, society values more highly in a painting than in actual (and highly endangered) nature. In Ulrich Wolff’s etching, whose broad landscape format suggests the expanse of the sunflower field, the added yellow field is a clear pointer to the original luminance of the blazing flowers and stands for the life-giving energy of the sun and “a symphony in blue and yellow,” as van Gogh described it and as it arises in our imagination.

Views into dense forests and single gnarled oak trees that extend their branches like the swaying arms of an octopus also belong to Wolff’s nature motifs, which roots his art deeply in European landscape painting. From the Danube School via the Arcadian landscapes of the 17th century and Caspar David Friedrich’s bizarre oak silhouettes to the Barbizon school—the artistic fascination for trees correlates to the myths that have emerged around these large and ancient organisms, far beyond Europe and indeed in almost all cultures in the world. In antiquity, forests were regarded as sacred seats of gods, and specifically, oak trees were associated with the father of the gods, Zeus. In the Old Testament, the allure of the fruits of the tree of knowledge caused the self-empowerment of humans and their sinful abandoning of God’s protection and care. In Nordic mythology, Yggdrasil, the Norse tree of life, embodies the entire universe. For centuries, trials were held, and justice meted out, under old linden trees, and Buddha found enlightenment under a bodhi tree. To this day, a tree is often planted to celebrate the birth of a child, and “family trees” are drawn up to trace the genealogy of families. Even though trees are part of human lives as a matter of course, and humanity identifies with trees globally, they are nonetheless ruthlessly exploited as a raw material, and mercilessly lumbered. Their exploitation has reached a threatening degree, and climate change aids this development in an alarming manner. Burning forests far in excess of natural levels are now a common sight on all continents, devastating large areas of land. Against this background, Ulrich Wolff stages the trees and forests in his photographic etchings like nature photographs from a long-ago past. The fallen twigs, lurching branches, and dense forests seem to become blurred behind a billowing, partly sulfury-yellow mist. The fragility of their beauty and the vulnerability of their dignity can be perceived all the more clearly behind these menacing veils. In his representations of nature, the artist intentionally foregoes the representation of human beings whose presence is merely implied.

Wolff’s depictions of nature contain clear references to the interdisciplinary approaches of ecocriticism and the environmental humanities, which were first established in literary studies, and in recent years led to the scholarly field of plant studies. Before the background of the increasing endangerment of global ecosystems, this field concentrates on the interplay of humans and nature, and examines critically the increasing

15

devaluation of the natural environment by humans, a result of the increasing separation of humans and the rest of nature. This is the case even though the life-sustaining significance of the phytosphere on earth is indisputable. The significance of plants in art and culture can be traced back to their significance as existential providers of oxygen and sustenance, as the basic condition of human life. In view of this global situation, the biologist and philosopher Andreas Weber argues for the need to rethink the interplay between nature, humans, and the economy, and suggests the intellectual category of Enlivenment: “aliveness” as a form of participation where humans are aware of being fundamentally part of nature, which they can influence, but from which they cannot separate themselves. The realization that we are not “above” nature, but must see ourselves as part of it, led the American philosopher and historian of science Donna Haraway to coin the term natureculture as long as twenty years ago.

Wolff’s frequently large landscape-format mountains or seascapes show that nature is easily thinkable without humans. In these works, the artist clearly draws on 19th century Romanticism. The motifs of an overwhelming, sublime, and seemingly timeless nature reduce the significance of humans in a way that could also be experienced as painful. In depictions composed like panoramas, the unlimited expanses of snow-covered mountains or shoreless sea horizons are abruptly cropped by the edges of the works, without any framing elements that might direct our gaze carefully into the depth of the image. This radical cropping suggests an unknown landscape that extends far beyond the section shown in the works, evading our limited human perception. In landscape painting, Caspar David Friedrich was the first to present a similar abandonment of limits in his painting The Monk by the Sea (1810, today in Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie), a work in which Friedrich uncompromisingly defied traditional conventions. The shock caused by this painting, which was perceived as radical at the time, and whose shorelessness impressed viewers deeply, was summed up famously by Heinrich von Kleist, who said seeing it one felt “as if one’s eyelids had been cut off.”

We experience a comparable sense of infinity when we view Wolff’s cityscapes of unidentified megacities. Enormous housing units also extend similarly mercilessly beyond the edges of the images, but they cannot convey any of the sublimity of nature. Humans create their own inhuman dwellings of oversized dimensions which dwarf them and threaten to make them disappear altogether. The etchings, whose effect is increased by the artist’s interventions, are characterized by an impressive, oppressive anonymity, where dark urban canyons swallow our gaze and make us dizzy. Only a few illuminated windows are evidence of warmth, light, and life, but the inhabitants themselves don’t appear. The hubris of the Biblical story of the tower of Babel suggests itself as a cultural topos of these motifs—even more so if we think of real, abandoned ghost towns, which were created in some parts of our world out of greed, a desire to make a profit, and which are already being blown up and torn down. Wolff’s calculated compositions, collages, and cropping of the architectural motifs, however, create an abstract formal vocabulary that, leaving their content aside, also communicate a visual beauty, reminiscent of statement of the Canadian-American painter Agnes Martin, who in 1989

16

wrote: “When I think of art, I think of beauty. Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not in the eye, it is in the mind. In our minds there is awareness of perfection.“

While in his cityscapes and landscapes Wolff foregoes showing people, in his portraits he reveals himself as an absolute humanist. He focuses on individual faces whose vulnerability he makes visible by way of extreme close-ups. In the series “Sieben Schwestern” [“Seven Sisters”] or “Opfer/Täter” [“Victim/Perpetrator”], but also in individual portraits outside of any context, he is interested in people as individuals. The enlargements cause the silhouettes to blur, and details to get lost, while Wolff’s interventions in the negatives and printing plates here again suggests an undefined past. The shapes of the people dissolve like our fading memories of them, like disappearing traces of life, of decline, of expiring. And yet: what remains is the intensive gaze of the people portrayed coming from the picture, at us who gaze at them—powerful, haunting pleas for life, for its dignity, its beauty and its preciousness, despite all temporal limitations: “There must be life!”

Translated to English by Wilhelm Werthern

Dr. Dorit Schäfer studied art history, classical archaeology and French literature in Heidelberg and London. In 1998, she received her doctorate from the University of Heidelberg with a thesis on The Ortenberg Altarpiece - Investigations into Middle Rhine Art and Painting Technique around 1400. Since 1998 she has worked as a curator at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, where she became head of the Department of prints and drawings in 2003 and curated numerous exhibitions ranging from medieval to modern art. Her work focuses on the drawings and prints of the Old German Masters, French art from the 18th to the 20th century and contemporary drawings and prints.

17

THERE

MUST BE LIFE

ARTWORK IN THE EXHIBITION

19

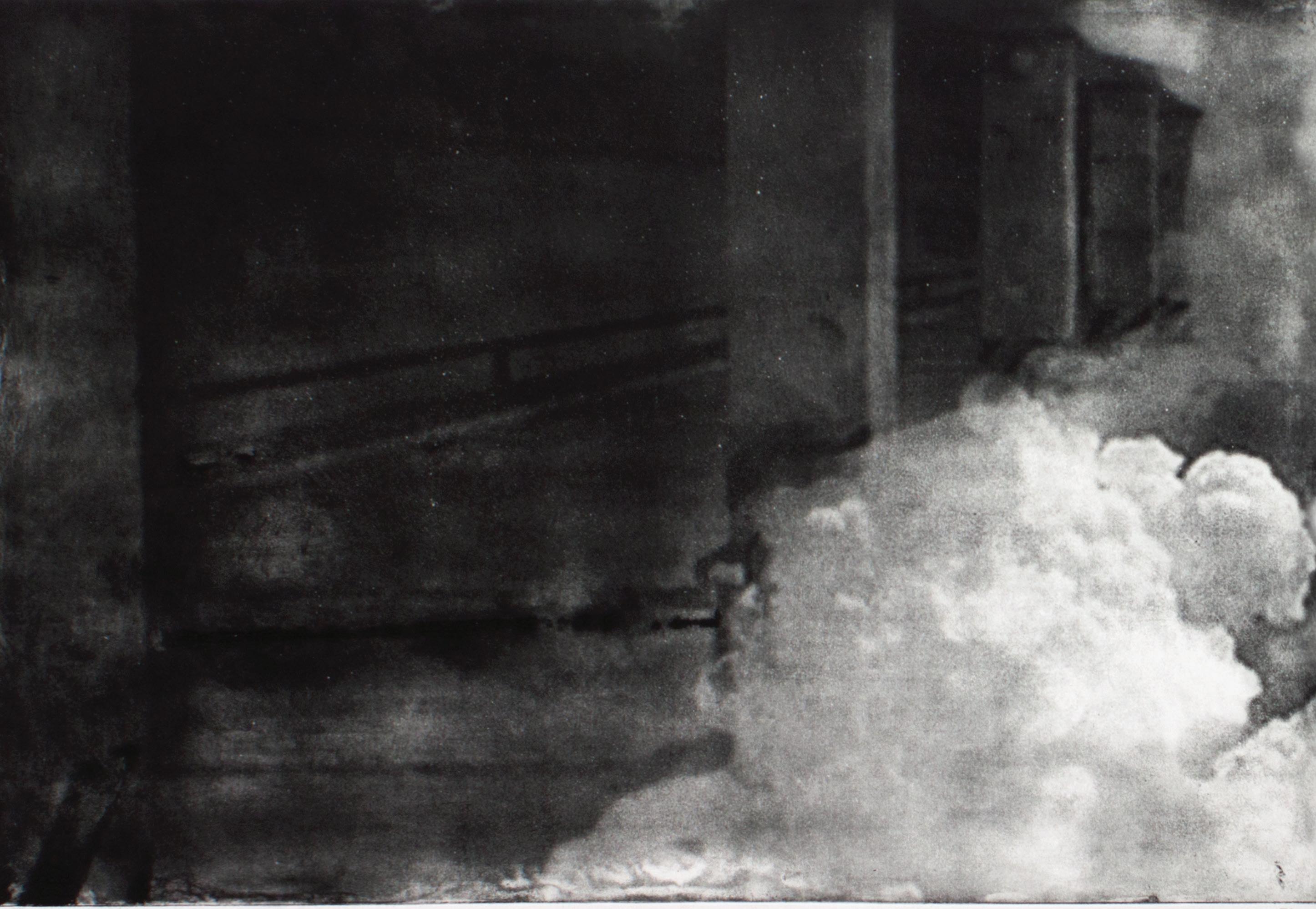

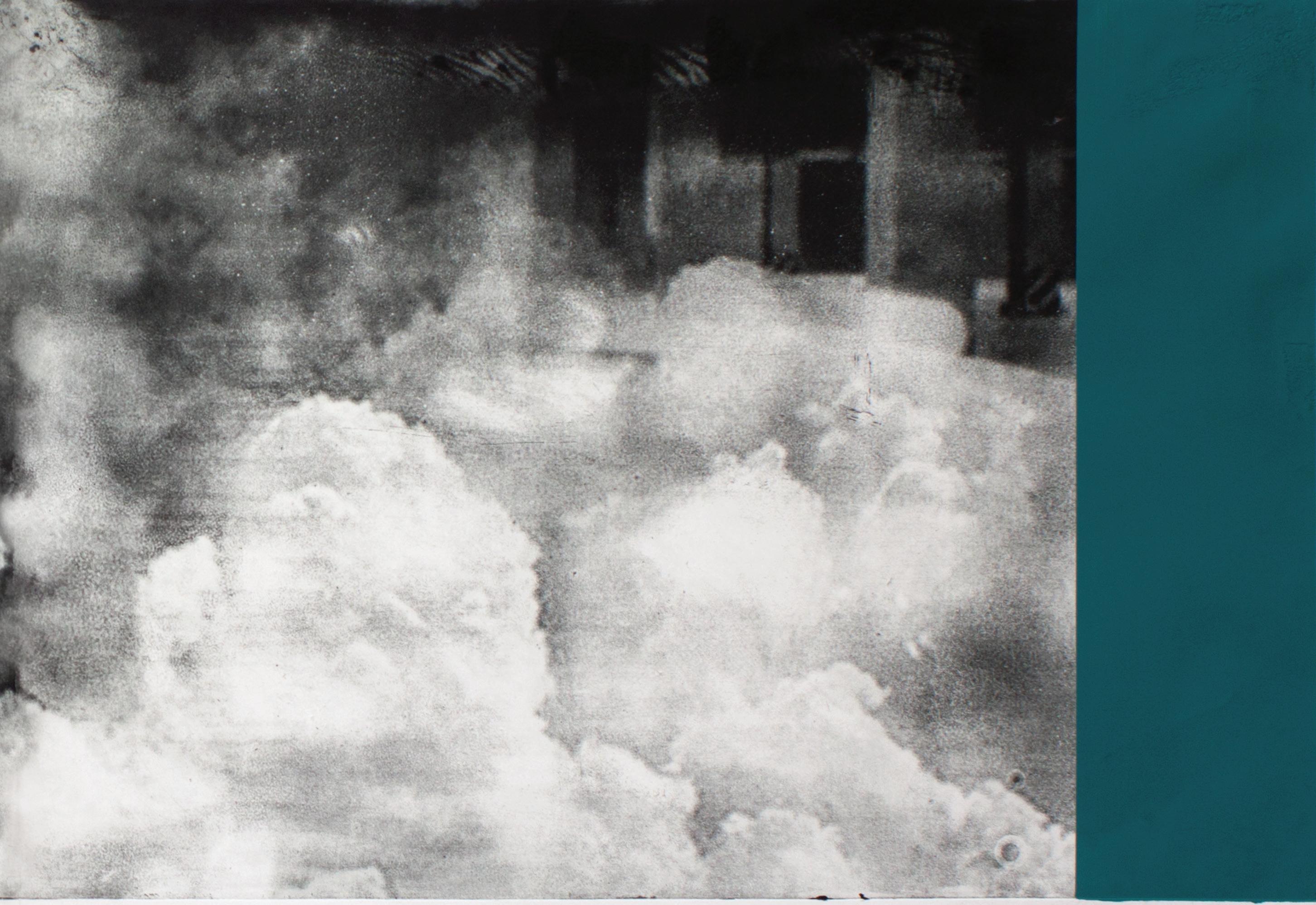

Cloud, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Cloud, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Shadow, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Shadow, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Long House, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Long House, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Library, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Library, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

City, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 156 cm

City, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 156 cm

Inner Space II, color etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Inner Space II, color etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Fasade, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Fasade, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

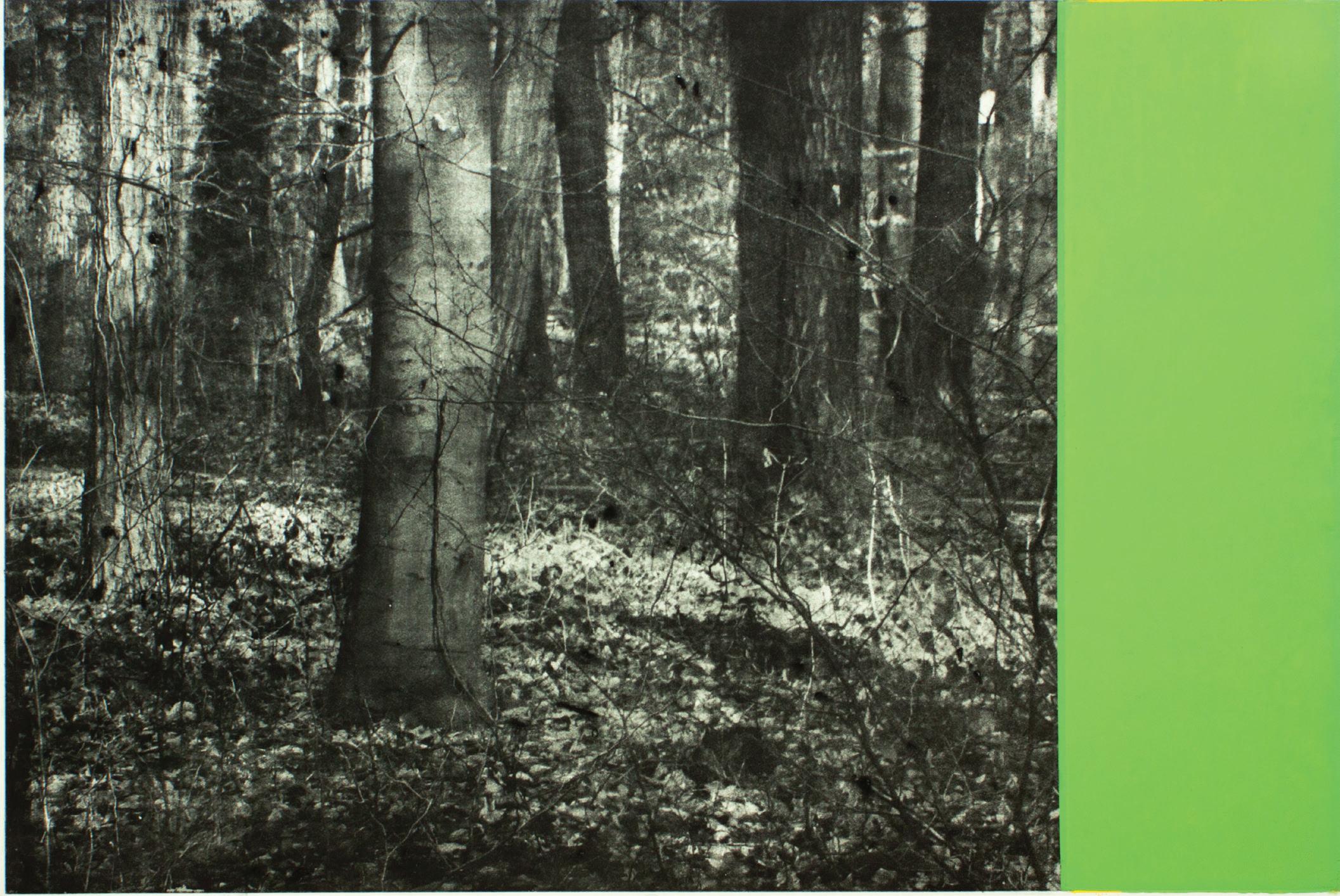

Beech, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Beech, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

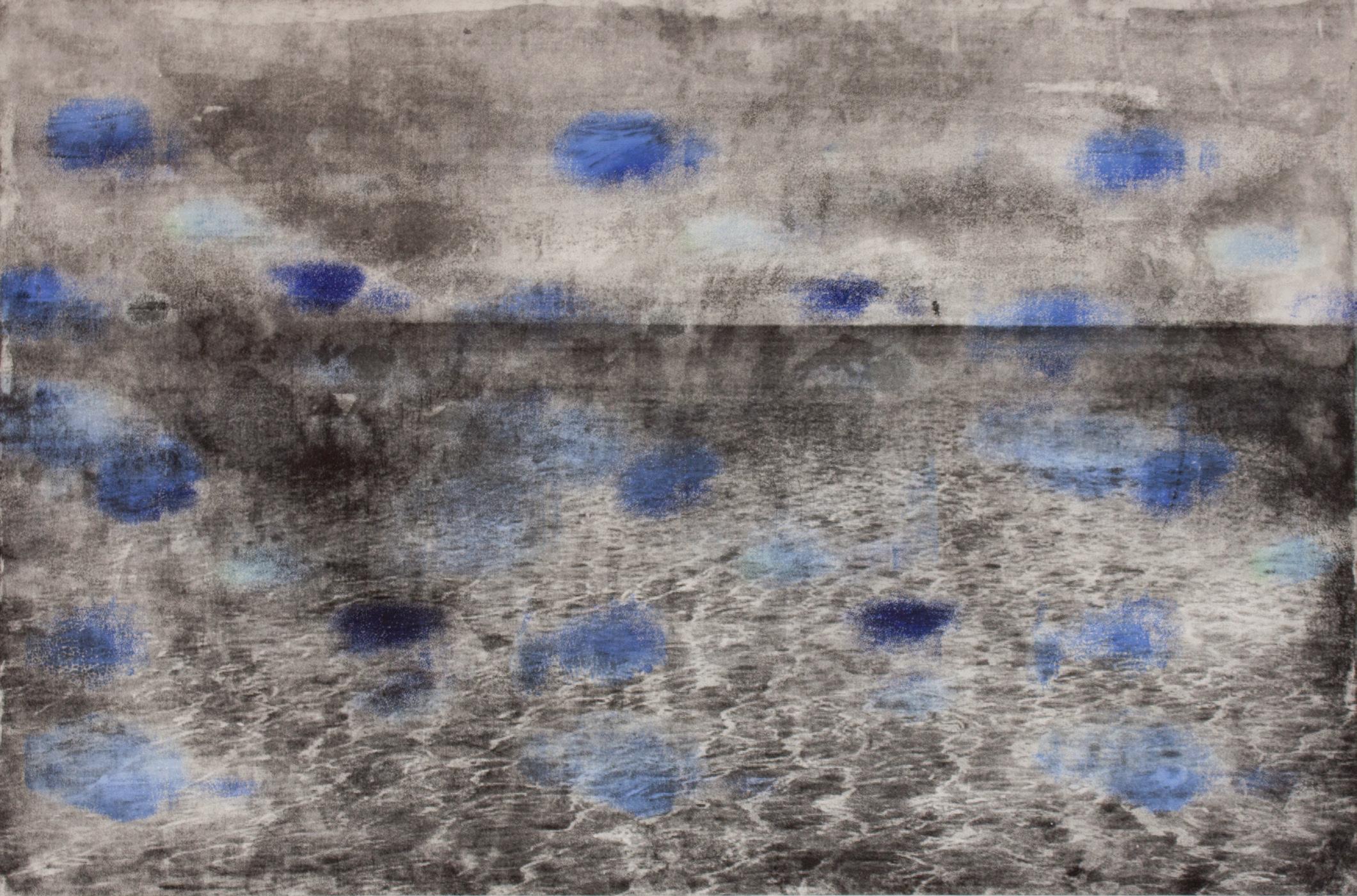

Black Suns, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Black Suns, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Field, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Field, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

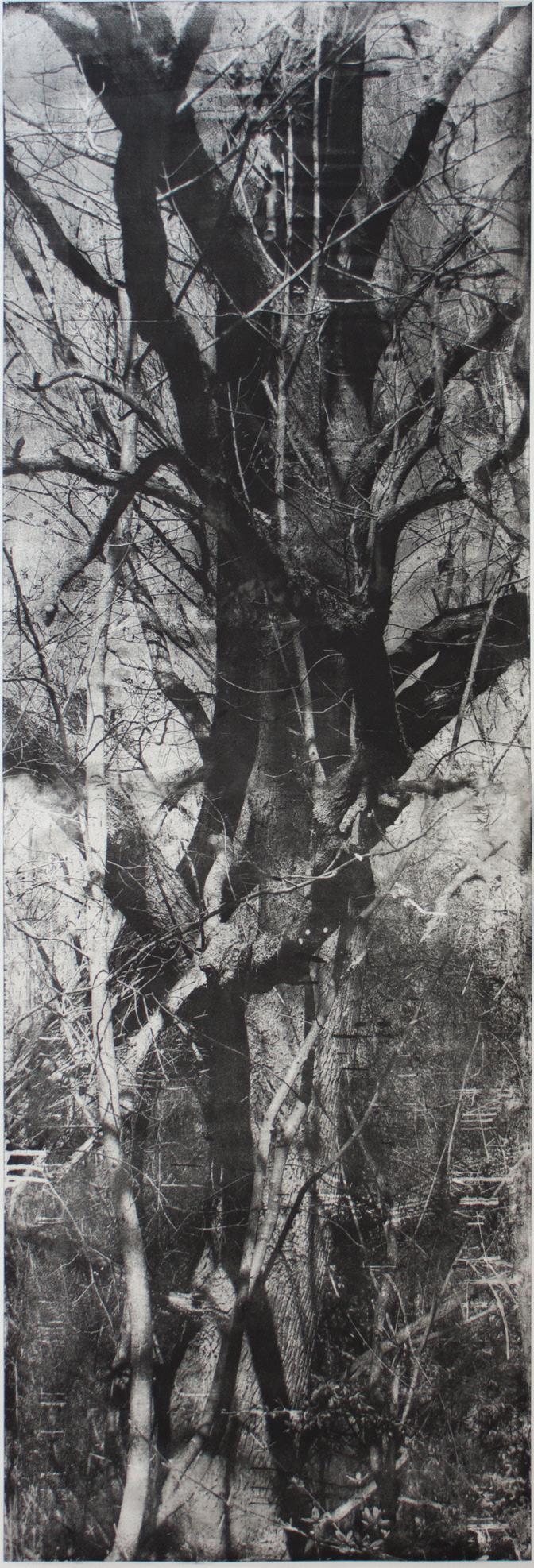

Big Tree, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Big Tree, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Crooked Tree, colour etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 156 x 108 cm

Crooked Tree, colour etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 156 x 108 cm

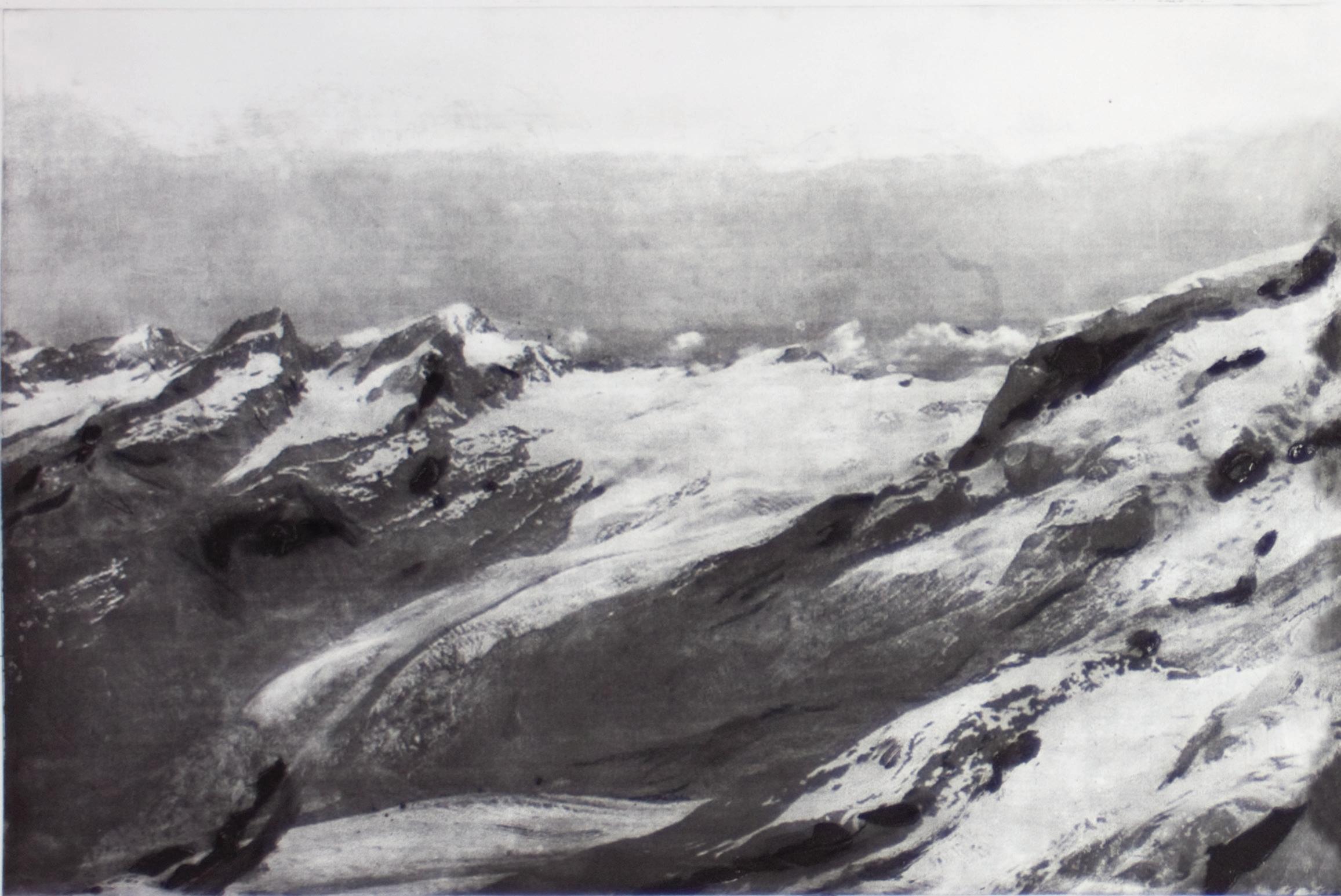

Mountains, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Mountains, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

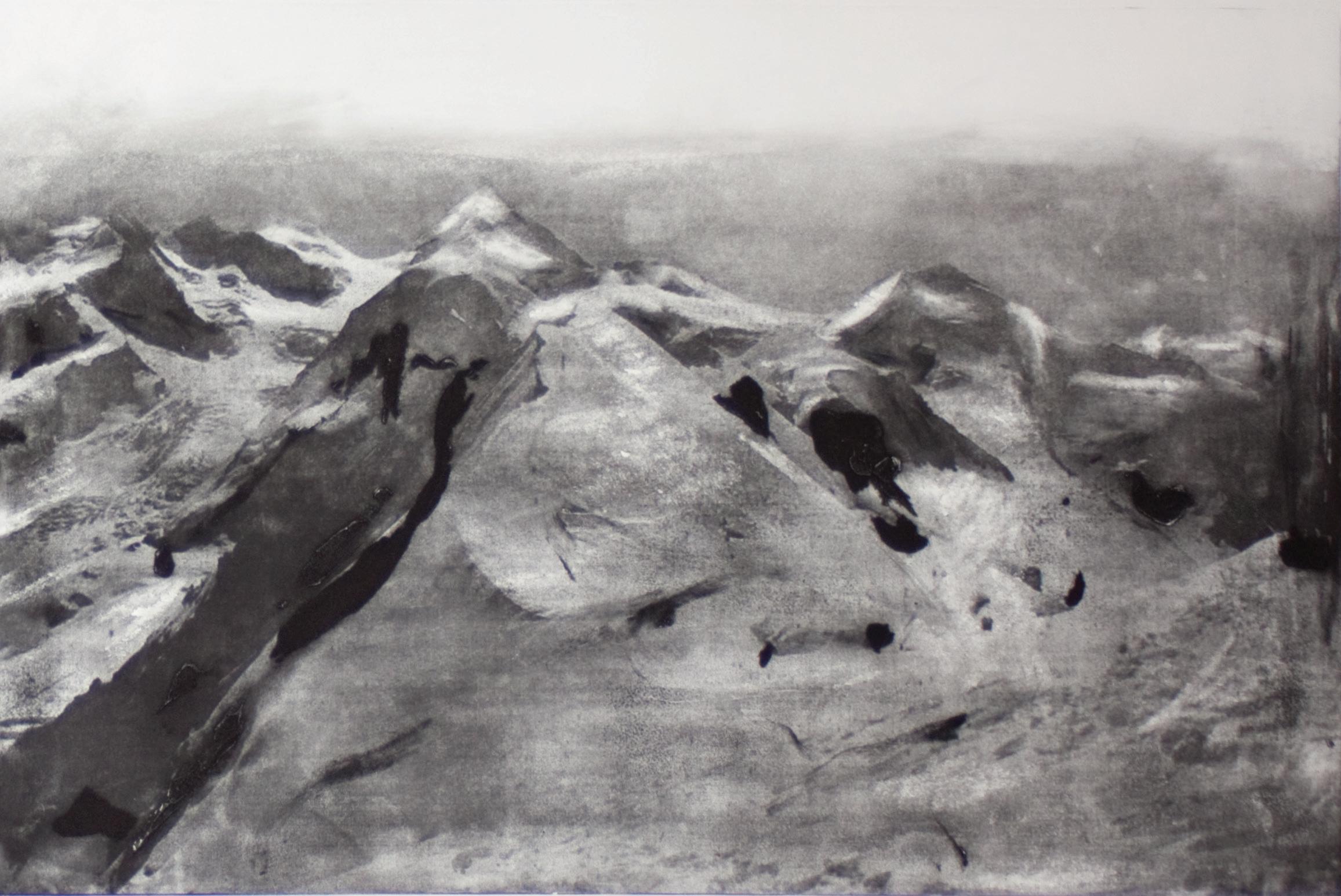

Mountains I, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Mountains I, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Kowloon Bay, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Kowloon Bay, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

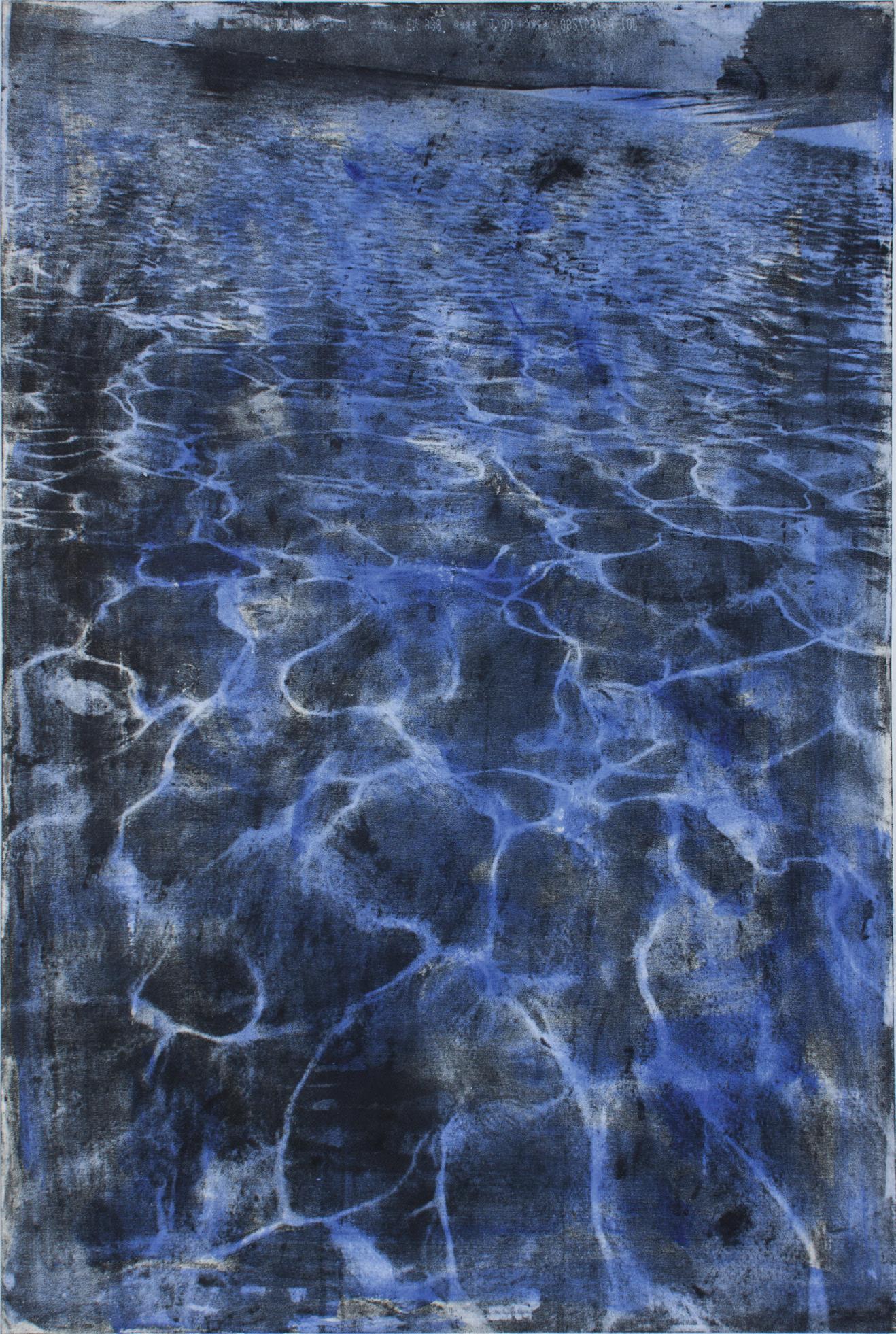

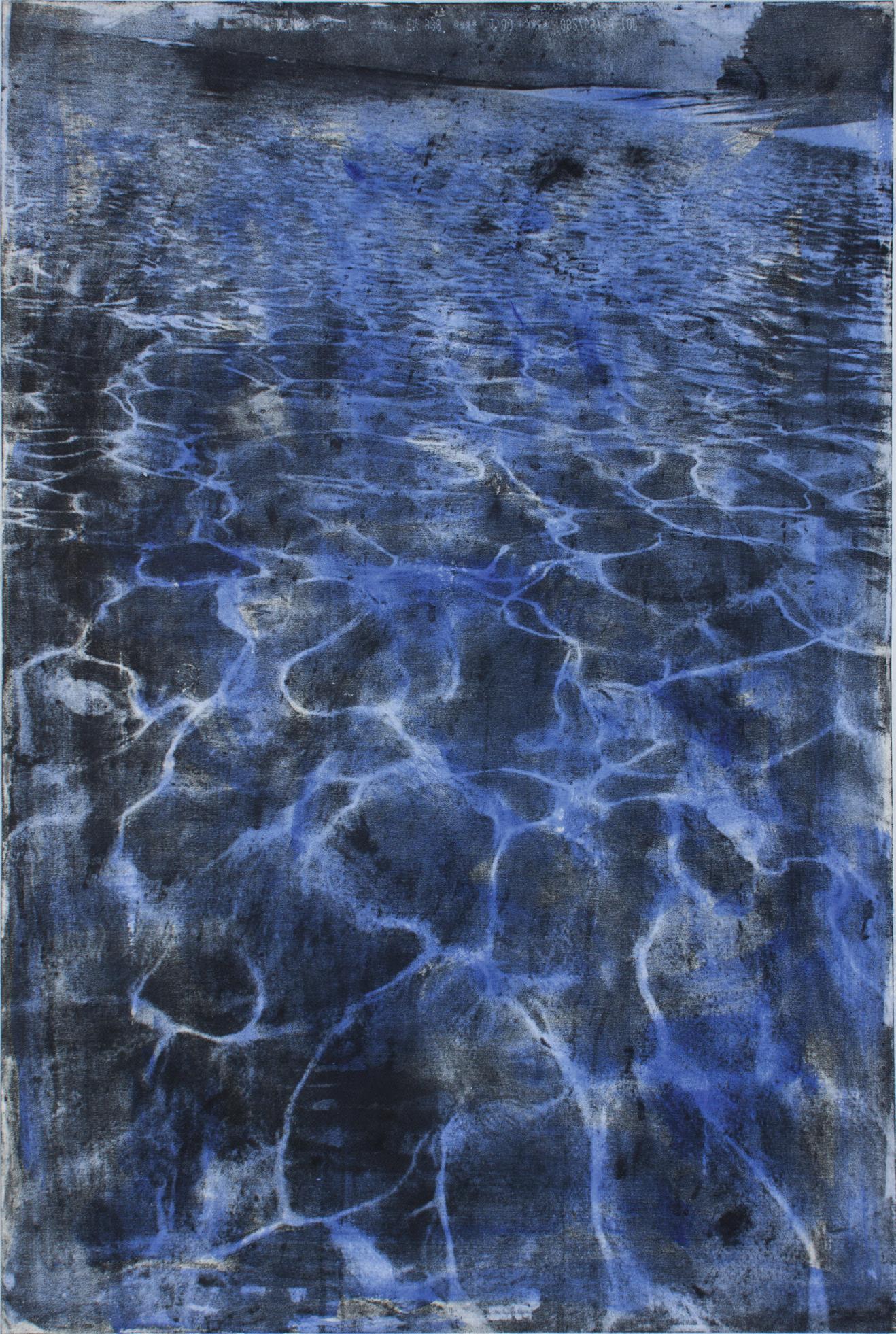

Water, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 108 x 78 cm

Water, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 108 x 78 cm

7 Sisters, etching photo aquatint/chine colle on handmade paper, text: screen print on transparency and handmade paper, each 68 x 46 cm, unique

7 Sisters, etching photo aquatint/chine colle on handmade paper, text: screen print on transparency and handmade paper, each 68 x 46 cm, unique

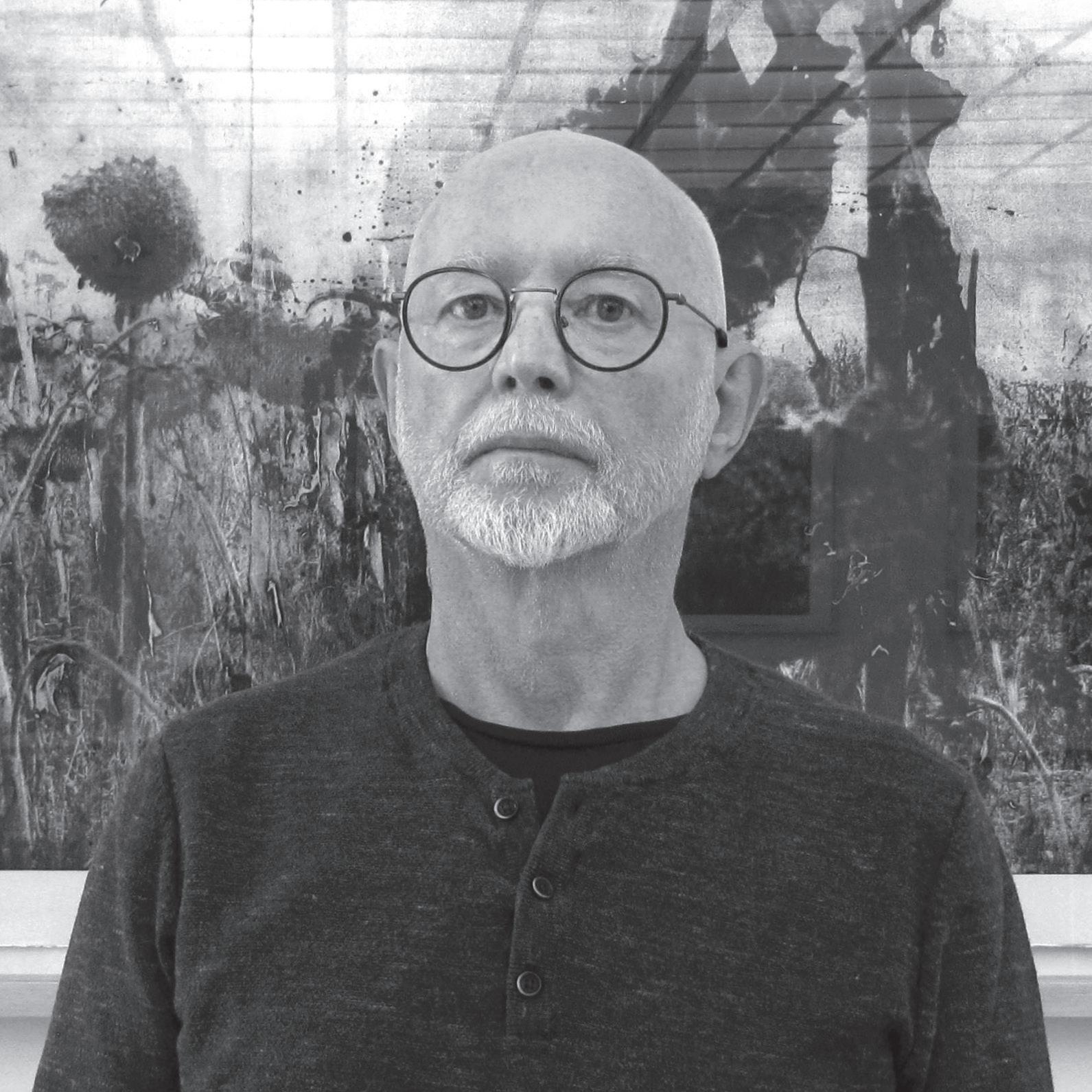

ULRICH J. WOLFF

Born 1955 in Schwaigern, Germany

CURRICULUM VITAE

Studied painting and graphics at the State Academy of the Fine Arts Karlsruhe, master student with Gerd van Dülmen

Teacher of etching and screen printing at the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe

Member of the artist federation Baden-Wuerttemberg

AWARDS

2024 Solo Exhibition Award Winner, Vernon Public Art Gallery, Vernon/Canada

2023 Special Prize of the first International Biennale of Miniature Art Graphics and Drawings Bitola/ Macedonia

2021 Winner of the OPT Okanagan Print Triennial 2021, Vernon/Canada

2021 Special award of the 10th International Graphic Triennial Bitola/Macedonia

2018 Artist in residence in the Guanlan Orginal Printmaking Base, Shenzhen/China

2017 Prize of the Jury, First International Print Biennale, Yerevan/Armenia

2017 Special Award of 8th Splitgraphic International Graphic Art Biennial Split/Croatia

2015 Grand Prize of Guanlan International Print Biennial, Guanlan/China

2006 Karlheinz Knoedler-Preis Ellwangen/Germany

2004 Kunst Forum Forst Kunstpreis Forst/Germany

2000 Heinrich von Zügel Kunstpreis of the City of Wörth/Germany

1993 Bronze Medal of 1st Egyptian International Print Triennale, Kairo/Egypt

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

Interesting Times – Graphics in Times of Crisis, Galerie im Gustav–Siegle–Haus, Stuttgart/Germany

Schichtung-Drei, Fotoradierung, Malerei, Druckgrafik, Kunstverein Germersheim/Germany

IPC International Mini Print 2022, Taipei/Taiwan.

Big Bang, Ein Universum moderner Druckgrafik, Der Sammlung Hartmann, Kunstmuseum Albstadt/Germany mini maxi print berlin, Galleri Heike Arndt Berlin/Germany

2. Print Biennale India, Lalit Kala National Academy of Arts, Jehangir Art Gallery-Mumbai/India

10th International Graphic Triennial Bitola 2021, (award winner) Bitola/ Macedonia

Vernon Public Art Gallery- OPT Okanagan Print Triennial 2021, International Printmaking Exhibition, (award winner), Vernon/Canada

International Triennial for Contemporary Printmaking Liège 2021, Liège Art Museum/Belgium

International Academic Printmaking Alliance-3rd Printmaking Biennale, Beijing/China

46

Second International Print Biennale Yerevan 2019, Yerevan/Armenia

The Second Xuyuan International Print Biennial, Beijing/ China

Wohin das Auge reicht - New insights into the Würth Collection, Kunsthalle Würth, Schwäbisch Hall

8th Splitgraphic, International Graphic Art Biennial, (award winner), Split/ Croatia

First International Print Biennale Yerevan 2017, (award winner), Yerevan/Armenia

1st International Triennial of Graphic Arts Livono, Bosnia-Herzegovina

International Print Triennial Krakow-Falun/Sweden, Dalarnas Museum Falun, Sweden

International Print Biennial Guanlan 2015 China, (award winner), Printmaker Museum/China

Highpoint Center for Printmaking, Minneapolis/USA

XII Baltic States Biennale of Graphic Art “Kaliningrad“, Kaliningrad Art Gallery Kaliningrad/Russia

VIII L’arte e il Tochio - Art and the Printing Press, Cremona/Italy

The Book of Seven Sisters, Coimbria Library University of Coimbria /Portugal

2nd International Printmaking Symposium “Out of the Studio”, Abbey of Bentlage/ Germany

Estampadura: European Print Triennal, Toulouse/France

Prints-without-Frontiers, International Print Network 2010, Krakow/Poland, Oldenburg/Germany, Vienna/Austria

Masterpieces of Art Printing, Gallery of the City of Karlsruhe/Germany

1th. Internationale Print Biennal, Maastrich/Netherlands

12th Internationale Triennale of Graphic Art, Grenchen/Switzerland

4th Graphik Biennale, Wakayama/Japan

Art Cologne, (1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1999), Gallery Dreiseitel, Köln/Germany

PARTICIPATION IN MORE THAN 270 NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS FOR GRAPHICS AND ART EXHIBITIONS:

Austria, Argentina, Armenia, Belgium, Brazil, China, Canada, Croatia, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Morocco, Macedonia, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Switzerland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, United States.

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

There Must Be Life, The award-winner exhibition from OPT Okanangan Print Triennial 2021, Vernon Public Art Gallery, Vernon/Canada

Welten Bilder, Fotoradierungen, Fridrichsbau Bühl, Bühl/Germany

Lebens Welten, Städtischen Galerie Tuttlingen, Tuttlingen/Germany

tin and paint, Gallery Knecht and Burster, Karlsruhe / Germany

Unikat Radierung, Drawing Sculpture, (with I. Ronkholz), Gallery Knecht and Burster, Karlsruhe / Germany

The Beauty of the Profane, Gallery Josef Nisters, Speyer/Germany

47

Graphics, Faculty Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, Krakow/Poland

Art Karlsruhe 2014, “One Artist Show”, Gallery Knecht and Burster, Karlsruhe/Germany

Town Person, Gallery Knecht and Burster, Karlsruhe/Germany

Painting and Unicum Etching, Gallery Julia Dorsch, Berlin/Germany

Town Person, Gallery Luther, Dinslaken/Germany

Radierung, Galerie Klinger, (mit E. Chillida) Görlitz/Germany

Neue Arbeiten 2008, Galerie Helmut Dreiseitel, Cologne/Germany

Unikat Radierungen und Bildobjekte, Galerie Königsblau, Stuttgart/Germany

Aiguaforts 1990-1994, Galeria Joan Gaspar, Barcelona/Spain

Color Etching, Museum Moderner Kunst, Passau/Germany

Etchings, Galeria Britta Prinz, Madrid/Spain

SPOTS, Gallery Helmut Dreiseite, Cologne/Germany

Two Length, Pictures and etchings, Galerie Netuschil, Darmstadt/Germany

Picture-etchings, Galerie Ruppert, Landau/Germany

48

VERNON PUBLIC ART GALLERY VERNON, BRITISH COLUMBIA CANADA www.vernonpublicartgallery.com

Cloud, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Cloud, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Shadow, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Shadow, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Long House, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Long House, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Library, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Library, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

City, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 156 cm

City, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 156 cm

Inner Space II, color etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Inner Space II, color etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Fasade, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Fasade, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Beech, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Beech, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Black Suns, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Black Suns, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Field, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Field, etching photo aquatint, screen print with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Big Tree, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Big Tree, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 216 x 78 cm

Crooked Tree, colour etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 156 x 108 cm

Crooked Tree, colour etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 156 x 108 cm

Mountains, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Mountains, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Mountains I, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Mountains I, etching photo aquatint with embossing on handmade paper, 78 x 216 cm

Kowloon Bay, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Kowloon Bay, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 78 x 108 cm

Water, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 108 x 78 cm

Water, colouur etching photo aquatint on handmade paper, 108 x 78 cm

7 Sisters, etching photo aquatint/chine colle on handmade paper, text: screen print on transparency and handmade paper, each 68 x 46 cm, unique

7 Sisters, etching photo aquatint/chine colle on handmade paper, text: screen print on transparency and handmade paper, each 68 x 46 cm, unique