RESILIENCE, ACHIEVEMENT, COMPASSION:

Unni Sonja Blegen grew up in Nazi-occupied Norway, facing both national and personal challenges as a young girl. She immigrated to the United States with her mother in 1951 and adjusted to new roles and customs as she navigated her teenage years. She met Lester A. Hoel, born during the Great Depression, a son of Norwegian immigrant parents from Bergen, and they married after a three-year courtship. Lester worked to complete his masters and doctorate degrees, and they raised three daughters while he went on to become a renowned professor and national authority on transportation engineering, authoring seminal textbooks on the subject. Here Unni tells their story in her own words, with a little help from Lester.

Iwas born on February 21, 1937, and His Majesty Harald V, the present King of Norway, was born exactly the same day, so everybody flew their flags. The flags were flown the year he was born, and every year after, even to this day. My father, Rolf Blegen, was cool as a cucumber, a very nice, kind person. He had his own import/export company and was easy-going. My mother was more highstrung. If you were late for dinner at 4:00 p.m., she would get very upset, because that is dinner time in Norway.

Growing up in Norway During WWII

Norway had a very big resistance movement, but it could only hold up against the Germans for about two months. The Royal Family was able to escape to England, and for a time Crown Prince Harald, his mother Märtha, and his two sisters lived with President Roosevelt in the White House.

People were speaking German all around us and I can still hear their boots on the streets. I remember it was very frightening, but you have to understand I was still a small child. The Germans treated the Norwegians better than the Poles and those in several other countries—if you remember, that was a gruesome time. They treated us better because we were the “Nordic race” and they thought that made us more like them, but they were wrong. My parents owned our condominium. The Germans let people with children of a certain age keep their apartments, but they took over all the other apartments, whether they were those of older people or of childless couples. As a result, we had German soldiers living all around, and they had parties—lady soldiers and men

soldiers. We could hear them talking German from our patio. The apartments were very close together.

When I was a very small child, I was allowed to go outside with my doll and my little doll’s wagon. The German soldiers would give children candy and my mother told me to never, ever accept it. You never knew what they were doing. You had to be very careful. Have you heard the name Quisling? He betrayed Norway, so we used to say you have to be careful of more Quislings. I heard from my parents that you couldn’t really trust your neighbors. You couldn’t really know if they were traitors or were on Norway’s side.

Every night when we went to bed, I had to have my clothes on and be all ready to go, because chances were there would be an alarm at night and we would have to take cover in the basement. It was a big cellar basement and everybody in the building had a little cubby hole where they kept some extra storage and food. So we went down there, and all of the

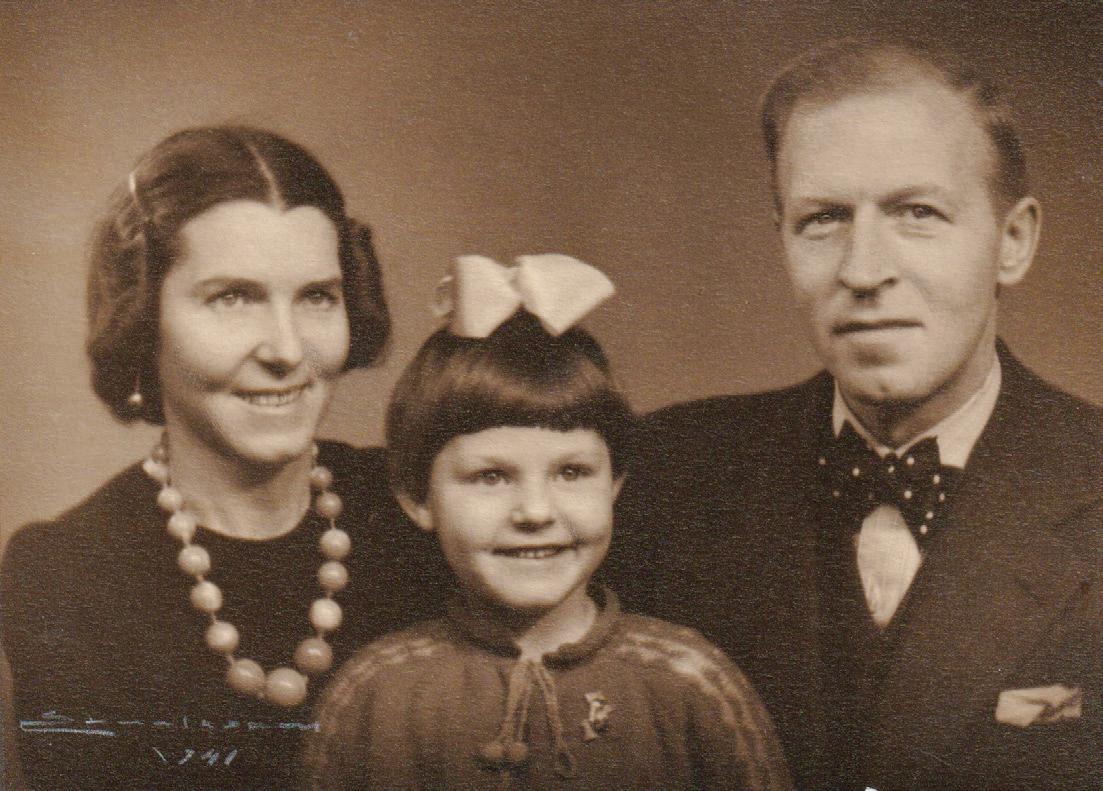

Family portrait: Unni with her parents, Sonja and Rolf. Photo courtesy of Unni Hoel.

Family portrait: Unni with her parents, Sonja and Rolf. Photo courtesy of Unni Hoel.

children used to play together. We weren’t quite sure what was happening because everything was blacked out—all of the windows in the hallways and the apartments—you could not see any light at night.

I am very grateful for the Marshall Plan, because that is how we got food during the war. We got a soup, it was a vegetable soup, we called it Beta soup. That is what they gave us at school. I was able to go to school, in all kinds of weather. There was not much food at all. One time my father went out to a farm and came home with a whole chicken, full of feathers, and it was amazing! That was the first meal of meat we had in a very long time. There was rationing in Norway. Of course we did have fish. My father was in the herring business,

so I had more herring than I ever want to think about. I don’t really eat it much today.

The bread you could buy in the stores at that time was mixed with sawdust. My godmother had ulcers, so she had a special dispensation and was able to get white bread. Whenever I visited her, it was like cake to me to have a piece of white bread.

As a sign of resistance, Norwegians wore red caps, and, if you had a red cap, you could be arrested. That was a Norwegian way of saying, “Please disappear.” My father was very calm about the war, but my mother was excitable and nervous. Once I was going outside and I remember my mother getting angry because I wanted to wear a red cap. All of the tram tickets had swastikas on them and one time I tore my ticket up on the tram. I can still remember to this day how my mother got completely hysterical, because if there had been a German soldier or spy on that bus, we could have been arrested.

But the war really hit home for me when my father and I, plus a friend of mine, went to see a play at the National Theater right in downtown Oslo near the royal palace. It is a very special theater. I said to my father, “Something is falling from the ceiling into my eyes.” That was the day of the big explosion in Oslo, in the park right outside the Royal Palace. The play stopped and the theater emptied. It was raining and we walked all the way to our apartment in the pouring rain and there was glass everywhere. We came home to a house full of water and broken glass—all the windows were shattered. My father was very handy and he was able to get some boards or cardboard boxes to cover them for the short term.

My father worked for the Norwegian underground. He went every night to hand out propaganda and to help people find shelter during the sirens. He could have been arrested for that. I wish I knew what was in my father’s propaganda papers,

because every morning, or every night before we took shelter, he tore up a lot of little papers and threw them in the toilet and flushed them down. At his office where he ran his herring import/export business, he had a radio hidden in the wall. One time the Germans came to his office and they actually beat him up. He came home all bloody, but they never found the radio. Now that I am older, I wish I had asked my father a lot more questions. It was a scary time.

When the war was over in 1945, the first thing I did with all of my friends in the apartment building—there were quite a few children—was to tear down all of those black-out curtains in every hallway, and we thought that was a really fun game. We were jubilant that the war was over. And we were able to visit with my grandparents, who lived a little outside of Oslo in Blommenholm. They had a big garden and we went there often.

When I was ten, my mother and I moved to my grandfather’s house. We lived there for two years. My mother and father had separated. My mother later moved to America to remarry, and I was left behind in Norway to finish school. I think my mother and the man who became her second husband had been sweethearts when she was 16, but he had

moved to America. At some point he visited her in Oslo and their romance was rekindled.

I lived with my grandfather, and partly with my father and partly with my uncle (my mother’s youngest brother). I had a long commute to school. I had to take a train and then the metro to go to school every day. That took over an hour from my grandfather’s house, but I wanted to stay in the same school. That was important to me because I had a lot of nice friends at the school.

My class at school had 26 girls. They all had birthday parties and I was always included, and even when I was at my father’s, he let me have a party in our little apartment. I used to go off to school and if I had a little money, a few cents or whatever, I could buy bread crumbs and cake crumbs, which was so wonderful—I used to share it with all of my friends. My school was divided, all of the girls in one class and all of the boys in another class. So sometimes we had snowball fights and fun like that. I remember one time somebody stopped me on my way home and threw snow in my face.

My grandfather was always working. Everybody, including my mother, said all we ever saw of him was his back. He had a nice house, but no central heating. So every morning at 5:30 or so, he used to put wood in the big oven and that heated up the whole house. My grandfather owned a big patent office in Norway, he was well known and had meetings with King Haakon. He was famous, and ended up in the papers a lot, so my friends used to love to come to his house. When I would invite them home, that was always a big treat. His patent office won a big case for Dupont. Instead of money for payment, he wanted a trip around the world. I still have all of the postcards he sent me from that trip. You can see how all of the cities have changed.

I wasn’t really lonely, but I lacked direction. I did what I wanted to do—a lot of ice skating and a lot of skiing, and my father took me tobogganing in the Oslo woods. Actually, I learned to ski when I was two years old. My father held me. I have pictures somewhere. It was just a different kind of life. A lot of athletic, outside activities—that was part of my life.

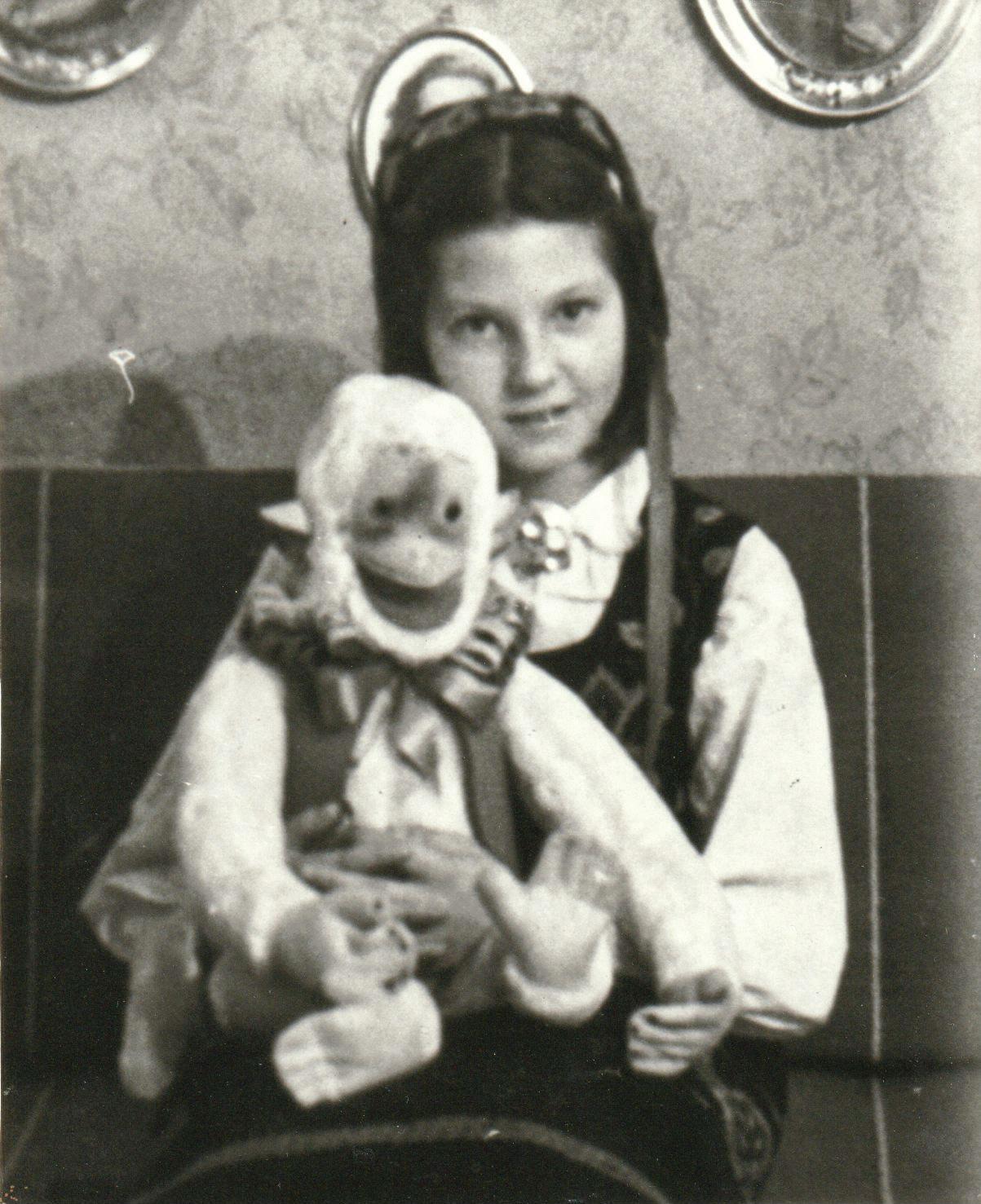

Unni visiting a farm outside Oslo. Photo courtesy of Unni Hoel.

Once, I came back from girl scout camp to find my mother had returned. I sat on my father’s lap and they told me my mother was going to remarry and move to America, and that I could stay where I wanted. But my mother said, “Of course she is coming with me.” That was the first I had heard about it. Her new husband-to-be, George, lived in Brooklyn and had a family himself, with four children. My mother left for America and my grandfather was going to take me there, but he had died right before Christmas on December 23, 1950, so my mother had to come back to bring me to America.

I came to America in September of 1951 and it was a big adjustment. I was just 14 years old. George picked us up at the pier and he was not in a very swell way. I can still remember we were charged $50 for a taxi coming from the pier to Brooklyn. That was a fortune in those days. We were immigrants, so they were just taking advantage of us, but George paid anyway.

George was one of those old-fashioned people, where “No wife of mine is going to go to work.” In Norway, my mother had worked at the patent office for her father as a translator. She was very good, fluent in English and German and Norwegian. Now she was just home. After a while, all my mother wanted was to go back to Norway. She didn’t like it in America. She did return to Norway with George, after I was married with three children all under the age of two—what timing, as there was no way I could return to Norway! She was 84 when she passed away in 1985. George died four years later.

As a teenager, it was very difficult living in a home where I wasn’t really wanted. My mother had gone through a lot of things in her own life, so it wasn’t that easy for her, and she had this teenager to contend with. I was lucky because I don’t like to dwell on the past. I could think things away. I feel I have really been on my own since I was ten years old, honestly. My mother left for three years to go to America and I was shifted around between my grandfather, my father, and my uncle. I was independent.

My mother didn’t understand about American schools, so she took me to a grammar school, and they said I was too old for that, so we had to find a high school nearby. I was fortunate, I met some nice friends. One nice young man I met

belonged to an organization at the school called “Be Kind to Each Other,” a Christian organization. He introduced me to his family and his aunt and uncle, and they became almost like second parents. They were of Italian descent and were absolutely wonderful, and that helped me a lot.

That is how life was: I came over, I managed. I had friends. I picked up the English pretty quickly. I had studied English in grammar school in Norway, but I didn’t know American slang. I had to go to all of these classes where I had to talk.

We were used to having respect for the teachers in Norway, so whenever the teacher came into the room, we all stood up. It was a matter of being polite. Here, when the teacher left the room, the kids threw their books in the air and became wild. I was almost scared. But it didn’t take much to excel at that school.

I became the manager of the bank staff and a representative to the Red Cross for the school, collecting donations for various causes. I was trusted and a mathematics teacher put me in charge. Another student and I were representatives for the Red Cross in high school. We were good friends. As representatives, we had to go into Manhattan to the Red Cross headquarters for meetings. I still remember the stares we got on the subway, because he was Black. It was very disturbing then, and it still is today.

In high school, I got a job with a big publishing company and they hired me back the next summer. I had some good secretarial skills. In those days people felt you had to get married eventually, maybe Mr. Right would come along, but I got a job at the New York Times after high school. I worked for the photographic department and that was interesting. The New York Times gave me a scholarship to New York University, which lasted just half a year: I had still to work from 10:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. every day. I was young and I wanted to have fun, so I quit. I realize now that was a young person’s decision, but times were different then.

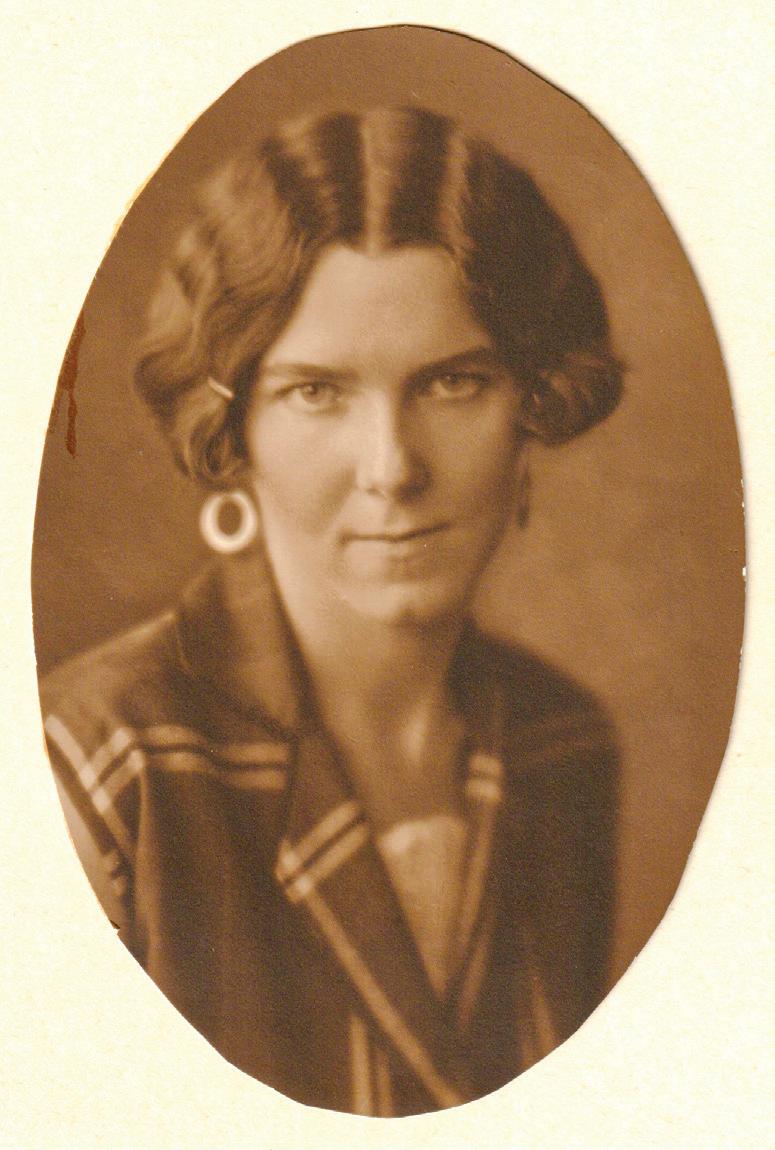

Unni’s father, Rolf, who was quite athletic, enjoying running and sailing.

Photo courtesy of Unni Hoel.

Unni’s father, Rolf, who was quite athletic, enjoying running and sailing.

Photo courtesy of Unni Hoel.

Lester was born in Brooklyn in 1935. His parents were Norwegian immigrants from Bergen. Lester’s mother came to the U.S. with her sister from Bergen. They were just going to be in America for a short time, but they both met husbands here. Lester’s mother met his father in Chicago. He was a very skilled cabinet maker, making pianos and very fine furniture. They later moved to New York. There were four children, but one died at birth: Lester was the middle child, with an older sister and a younger brother. The family was very poor. They had a very small apartment in Brooklyn in the same neighborhood as their church. Lester’s father was extremely religious. He worked way out on Long Island and commuted. Lester always wondered why couldn’t they have a small house nearer to his workplace, but the church meant more than anything else to his father.

Lester knew he was not going to live in poverty. He was going to get a good education, and got one through the City College of New York, which was free at that time. He went on to get a doctorate at Berkeley. He is a self-made man, a very successful engineer, professor, and researcher, and has written many books on civil engineering and transportation. He has accomplished a lot during his life. I met him at an early age, and I am happy we were a great team.

When I was in my late teens, I met Lester at a youth group. It was a Christian group, but not a church, and we went every once in a while. That day, I went with a girlfriend, and they had music. Lester sat a few seats over from me and I could sense that he was looking at me. When the meeting was over, we stood up and started to talk. And it turned out his parents were from Norway, Bergen to be exact, and of course I was from Norway, so we had a few things in common. Lester had a car, which was very nice, and he asked if he could drive me home. We went to have pizza, and then he drove me home, and he asked for my phone number. I had some other suitors at that time, but Lester won out. He was a kind and wonderful person.

Lester recalls:

At 19 years old I had the best luck. She agreed to ride home and I was smitten. First thing I thought is why don’t we just stop and have pizza, and get to talk a little. So, we did that. My brother was with me, he was just there. I think she decided when she saw me I was trustworthy. She saw I had friends in the church, too. It was a defining moment in our life. If she had said “No, I don’t give phone numbers to boys I have just met,” I would have never seen her again.

I was born on February 26, 1935. And if I may say so myself, anybody born on that day in the middle of the depression would have said, “I don’t want this life.” But being born at the worst time turned out to be the best time. Sometimes you don’t realize what looks like the worst time for you could be a best time. Why do I say that? Because the birth rate in that era, in the 1930s, was the lowest it had been probably in American history. What does that make me? Scarce! There weren’t that many of me around.

I was just a student, going to City College of New York and Brooklyn Polytechnic. My persona was a hard-working kid. I had a lot of jobs. That car I had, I worked for, bottling 7-Up all summer long when I was in college. I saved all

my money until I had $1,000, and I bought that car. I wanted to be an engineer, so I got into Brooklyn Technical High School and I graduated from there, and I wanted to continue on that path and went to City College of New York, and got a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering. I then came out to Berkeley and got a doctorate. I love to teach which is why became a professor of civil engineering.

My courtship with Lester lasted three years. After Lester graduated from the City College of New York, we got married on January 24, 1959, in the Brethren Church in Brooklyn, NY. We had a small wedding and had our reception at the Norwegian Seamen’s Church in Brooklyn. Our friends and family came, including my mother and George. Lester and I have been married for over 61 years and we feel lucky that we made the right choice at the right time. There is a meaning in life.

After we got married, Lester went to Brooklyn Polytechnic University at night to earn his master’s degree while I was still working. Later, on a scholarship at Berkeley, he earned his D.Eng. and taught.

While I had been living my life in America, I had not heard from my father for 13 years. He felt, once I got to America, it might be too confusing or difficult. My father missed me a lot. After we got married, Lester had a Fulbright to Norway and my father was there on the tarmac to meet us, which you could do in those days. He was the sweetest person, and Lester loved him right away. My father explained why he hadn’t been in touch—he didn’t want to upset my life. And we got to know him better later on, because, when he was 70 years old, we sent him a ticket to visit us in Pittsburgh. Lester was a professor at Carnegie Mellon University at the time, and the Director of the Transportation Research Institute. My father stayed with us for three weeks. The girls got to know him and he loved them. Sonja and Lisa and Julie will still remember having him play with them. I got to know my father all over again. My father died eight years later at 78 years old.

Because Lester decided to earn his doctorate at Berkeley, we took all of our belongings in a little black Plymouth with a red interior. My uncle Charlie made a rack for the roof. We sold all of our furniture and planned to buy what we needed when we got there. We just drove across the country. On the Pennsylvania turnpike we ran out of gas. We will never forget that. We learned the hard way and that’s why we always have a full tank of gas in our car.

Having been on my own, fending for myself since I was ten years old, I had an independent streak. One weekend I was very upset Lester was going to the computer center again—he had thousands of cards to compile—and I wanted some fun. Lester had been working all of the time, even on the weekends. I thought it would be nice if he had a little more free time. So I took a bus to Carmel by myself. Stayed in the Pine Inn, had a wonderful time for two days. I met a very sweet lady who was by herself on a little vacation. She was going to a concert and asked me to go with her. It turned out she lived Berkeley, so when we were both leaving the next day, she offered to give me a ride home. The funny part was, Lester had expected me to come by bus at a certain time. When instead he saw me get out of a car in the little courtyard in front of our apartment building, he got a little scared, I think. After that, you know, he took a little more time off.

At one point in his doctorate work, Lester thought he was going to quit, and I said, “Don’t you dare!” He did not quit. We are a good team. He later became a professor at San Diego State.

San Diego and Julie’s Birth

We were living in San Diego when President Kennedy was shot. Lester was teaching and I did volunteer work. I was the president of the newcomer’s group and also going to school, and then I found out I was pregnant with Julie. I stopped going to school, and Julie was born on June 6, 1964. I had been a “Pink Lady” at Sharp Hospital, and met two lovely friends there who were also “Pink Ladies.” At that time Lester was doing a lot of consulting work in addition to being

a professor, so he was gone quite a lot. When he was gone, I stayed in their homes. They took care of me like a mother would. I can still remember one of them had an electric blanket, which was heaven. I had never had an electric blanket in my life!

Lester later got an associate professor position at Carnegie Mellon University, so we moved to Pittsburgh in 1966. We had a little Volkswagen, and Lester drove it across the country while I flew with Julie. We rented a house in Monroeville, in an area called Garden City, and I was pregnant again, and I had to find a new doctor. They didn’t know me, and in those days they did not have sonograms. The pregnancy was troublesome and I was told I had to be off my feet. Lester then came down with double pneumonia and was in an oxygen tent. It was not the best time of our lives, but our neighbors were very friendly and kind to us, taking me to visit Lester and watching Julie so I could rest.

Soon my water broke and I went to McGee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh. Men were not allowed in delivery rooms in those days, so Lester left me and went to work. Sonja was born, and then the doctor said, “There is one more baby here.” Lisa was a breech, so she was a big surprise. All I remember is that the operating room was filled with people and doctors, but I had a natural birth. They had to move Lisa—she had jaundice and some problems at birth, so she was in incubators for a rather long time. Today she is fine, but the doctors were not sure she was going to make it at first. That birth was over 50 years ago.

The story goes that Lester was at his office when the doctor called him, and one of Lester’s colleagues answered the phone. The doctor told him that he had twins. His colleague told Lester, “Sit down and talk to this man,” and handed him the phone.

Lester recalls:

Your first child was like, “Oh man, that’s terrific! Oh finally we have a child!” The next two were kind of like, “Oh my God, you’ve got to be kidding! Twins! And a twoyear-old!” In fact, I got the information on a phone call in my colleague’s office, and he knew what the doctor was going to tell me. He said, “Les, sit over there and take this phone call,” and then he tells me I am the father of twins. I looked at him and said, “What do I do now?”

Lisa had some kind of needle in her head for weeks. The twins were in a hospital near where my office was, so I could go over there and check them out. They were in incubators and it was touch and go. The doctor told me he wasn’t sure one of them was going to make it. And you know what I did? I fired him. I didn’t want a man like that telling my wife they don’t think the babies are going to make it. It was so surprising to me. It was a time of uncertainty, a time of a new job, a new place to live, so much change going on. But it all worked out.

We had been quite happy in Pittsburgh. Lester had gotten promoted to a full professorship at Carnegie Mellon, I was active in the women’s organization there. We had a good

life, we built a nice home. But Lester was approached by the University of Virginia—those were the years when you didn’t really apply for a job. Initially he was asked to come give a lecture. He wasn’t really looking for anything, because we were quite happy. At first he said no, and then the dean called a few more times. Lester went down to meet with them, and then they wanted me to come to Charlottesville. We left Pittsburgh in an ice storm and it was very cold, and we came to beautiful Charlottesville, where everything was in bloom—it was just gorgeous! I was sold.

It was a big adjustment coming from across the country again, but we built a very nice life in Charlottesville. We lived there for 35 years. Lester was chairman of his department for 16 of those years and he wrote his prolific text books there.

When I first came to Charlottesville, I didn’t know anybody from Virginia. It was very different from Pittsburgh. It was a southern town at that time, the university had just started admitting women in 1974, there were biases everywhere. At that time some people in Charlottesville were racist. It was very sad. I remember going to events where some would actually talk about Black people with little respect. That bothered me—our best friends in Charlottesville were Black, and they are still among our very best friends today.

There was a woman in town who opened a little Norwegian store, Ellen. I went down there to see what she was selling and she had julenisser, trolls, and some Norwegian embroidery. She was so happy I was Norwegian. Then we found out there were more Scandinavians living in Charlottesville. The community was not very big, but we did

have professors visiting from Europe and Norway and so forth. After a few months, she invited all of us to her condominium for a party. We all met and from there we all bonded. We decided to meet once a month. All of us Scandinavians—there were Swedes, Danes, and Norwegians—became like sisters, very close friends. To this day I hear from them all of the time.

We had three children—Julie, Sonja, and Lisa. I do feel that you wouldn’t know my three children are in the same family, because each one of them is so distinctly different in their personalities and their way of living.

Julie, who is the oldest, liked to run away and climb on things, kind of a tomboy when she was little and now has a biology degree. Lisa is sort of an artsy person. She got her degree in nursing at the University of Virginia, but she decided she didn’t want to be a nurse after all, so she went to the London School of Communication Arts and got into advertising. Sonja has been a businessperson ever since she was small. When she was little, she used to say, “Mommy, when I grow up I am going to make a lot of money.” Sonja earned a MBA from Harvard Business School and became a venture capitalist. And I must say, you know, the way you are when you are little…

Sonja was always neat as a pin. Her room was perfect. With Lisa, you had to wade through clothes on the floor, and Julie was our in-between. Julie loves animals, she just can’t live without animals. We always had a dog when they were growing up.

I didn’t really have a philosophy about parenthood, it was all new to me. Lester had a very strict upbringing, and I didn’t really have much supervision as a child, but it turns out I was the strict one. I wanted them to be home at a certain time, and I was nervous when they started to drive. I did the best I could. Trial and error, that’s how children grow. I wanted all my children to be independent. I wanted each one of them to have a college degree—that was so important to me and Lester. I wanted them to be able to be on their own if they ever needed to be. And I was lucky to have attained that. I was stricter than Lester, because I know what children can do when unattended. He was more trusting and very kind. The kids loved to sit next to him. He was the best father anyone could have. He really was. He had more siblings, but I was an only child and was never exposed to a lot of young children, so I kept learning.

Lester recalls:

The children would come to me because they considered me to be a little easier than Unni was. I am easy going, I let it happen, and so on and so forth. They would say something about Unni, “I got in trouble with Mom today, I didn’t do my homework and . . . .” And I would say, “Let me tell you one thing about your mother, people like her.” That was the end of the conversation. And that is very true. She is a very personable human being, very generous, very kind, open, a good conversationalist, a good hostess. Wherever we have been—and we have traveled around, when you add it all up it has been a number of places in our lifetime—we have always made friends and she was the one doing the hard work.

At 57, I had quadruple bypass surgery. When I went down on the gurney, I said, “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want, he maketh me to lie down in green pastures.

He restoreth my soul. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death (which is where I was) I will fear no evil. . .” That is the prayer. That is what I said.

Lester and I see things in the same way. We have learned a lot. Even though I don’t have all of his degrees, I have learned so much by being involved in the academic life. Most of my friends all have master’s or doctorate degrees—very intelligent people—and I have learned a lot being exposed to academia most of my life. He has learned too.

Lester:

I have learned that if you are kind and generous and willing to compromise, the world will love you. And that’s how she has been all my life.

Lester is now retired, a Professor Emeritus at the University of Virginia, and we live in San Francisco to be near our daughters Sonja, who lives in San Francisco, and Lisa, who lives in Berkeley, and our four grandchildren. Julie lives near Washington, D.C. We love to be together as a family on special occasions. Last year everyone gathered to mark our 60th wedding anniversary—three days of celebration. Looking back, despite the Nazi occupation, my parents’ divorce, and many other obstacles, my life has been wonderful. We visit family in Norway, and they visit us. One young cousin even attended UCLA and played soccer. Had I stayed in Norway, those family bonds no doubt would have been even closer, and my life would have been very different. I would not have become the person I am today. If I could look back and change anything in my life, I would not change a thing because I love how my experiences have shaped me as a person today. There is a meaning to life.