3 minute read

MY ANTARCTIC

Dr. Damon Stanwell-Smith, Head of Science and Sustainability at Viking Expeditions, reflects on his emotional connection with this icy wilderness

Clockwise, from

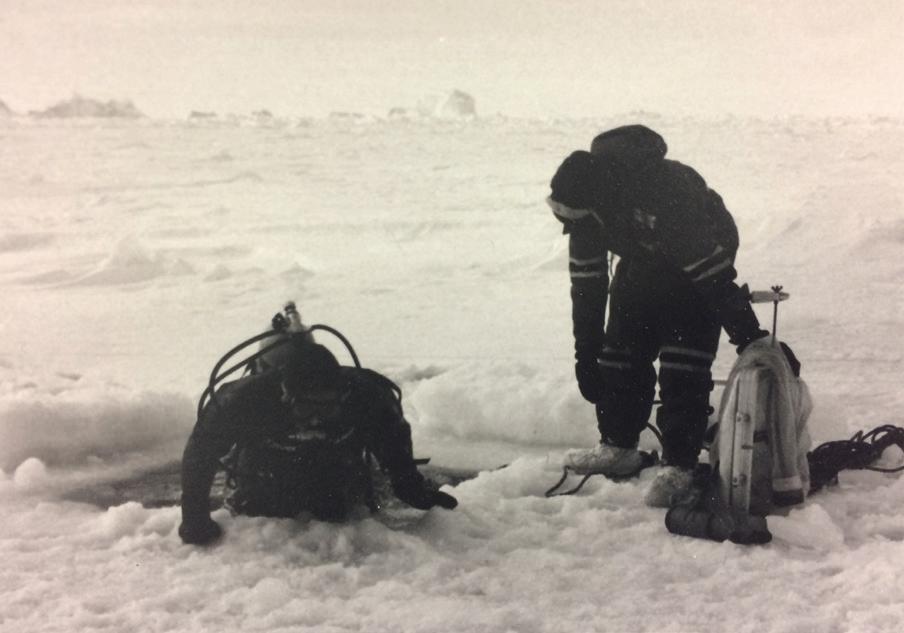

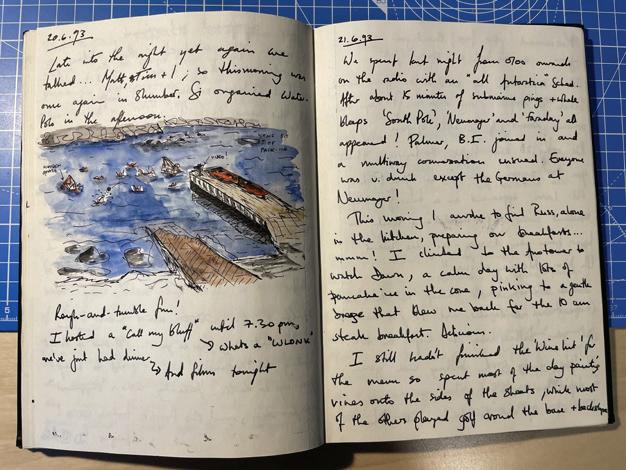

above: Damon and his wife Hannah; beautiful Antarctica; Damon emerges from an ice hole with a plankton sample; Damon (back row, second from right) with the British Antarctic Survey wintering team, Signy Base, 1993; Damon’s 1993 diary entry describing a (cold!) water polo match “I was an Antarctic diver.” A simplifi ed description of my early career, yet when mentioned in social settings nearly thirty years after I fi rst successfully applied for work as a marine biologist with the British Antarctic Survey, I still feel a tingle of excitement and the sense of immense privilege to have had the opportunity to experience the greatest wilderness on the planet.

In 1992, I graduated from a marine biology degree at university and was immediately plunged into the extensive preparations required for a deployment to Signy Base in the South Orkney Islands. With some pleasing symmetry, it included spending the summer in the (Northern) Orkney Islands, training in commercial diving within the deep and swirling waters of Scapa Flow. I couldn’t quite believe I was being paid to explore this diving Mecca of scuttled warships and Celtic mystery.

After the course, I spent a weekend with friends by the coast on the South of England. It was October, and we were jumping in and out of the seasonally frigid sea, and I was the one complaining the most about feeling cold. I was teased about my impending choice of subaquatic career and was privately crushed by shivering doubt that I was making a monumental mistake.

However, the Southern Ocean beckoned and I was swept along with the regimented excitement of the long fl ights south, then boarding an ice-strengthened ship across the fearsome Scotia Sea to eventually reach our island home for the next three years. Myriad adventures followed – of discovery and selfdiscovery – with thirteen colleagues and many thousands of penguins and seals.

My research investigated the planktonic, drifting larvae of the underwater invertebrate animals that thrive in Antarctic waters and I immersed myself in endeavouring to understand their way of life. However, my overriding memory of that time is the morning ritual of donning a neoprene drysuit and breathing apparatus and lowering myself through a hole chain-sawed through the sea ice. Swimming down, down. I can close my eyes and it is as vivid as yesterday, recalling those wind-swept icy sledge trips to our dive sites and the calm blue world beneath.

By 2005, my Antarctic love was expressed through seasonally working on an expedition ship as a specialist guide and expedition leader, indeed where I first met Jorn Henriksen, now Viking’s Director of Expedition Operations. Jorn and I were requested to supervise the in-water safety of a world-record swimming attempt in Antarctic waters by the remarkable athlete and ocean protection advocate, Lewis Pugh. Watching Lewis as he meditated prior to his recordbreaking swims vicariously evoked my own profound emotions of connecting with this wildest of briny places.

Being in Antarctica is a visceral experience, and so hard to describe to those who have not (yet) had a chance to visit. My partner has patiently listened to my tales of polar adventures, yet my words and the media images of the White Continent cannot truly convey its majesty. And so, in 2019, we travelled South together and were married, in the old Whalers church in Grytviken, South Georgia. We continued on to the Antarctic peninsula, and it was a joy to see my wife splash into the sea for a most brief of ‘polar plunges’. Once again, memories of diving under the ice fill my mind.

I am now sitting at my desk in Cambridge in 2021, cocooned in the pandemic-induced isolation we have experienced recently. Remotely, I work with Viking colleagues to prepare our expedition vessels in readiness for voyages next year and beyond – and I am once again reflecting on cold waters. My wife has found that swimming in our local rivers has been her salvation. I am once again teased for finding the local waters rather too cold, and yet I still dream of the White Continent. “I am an Antarctic diver.”