6 minute read

Megaform and the grid : Barcelona

L’Illa

Diagonal, Barcelona, Rafael Moneo

Advertisement

The concept of megaform as per Kenneth Frampton is understood through a set of characteristics that distinguish certain projects from being portrayed as megastructures. He also says that our capacity to imagine megaform may well have originated with our first experiences of the world as seen from the air.1 In addition to perceiving the size of buildings from the air, another element that is easily understood and analyzed from air is the grid of cities, the surrounding topography and landscape, layers of land seen from up above which sometimes merge with certain buildings giving them a characteristic of being a megaform. Grids act as perfect multidirectional systems that sometimes, through their irregularities, hierarchy and differentiation give meaning to the city while searching for a balance

The core argument comes down to the concept of size against its integration in the urban grid and grain. The question of how do megaforms function and establish a relationship with a preexisting grid can be looked at through Moneo’s L’Illa Diagonal, a project with a complex urban program sitting on a wide trapezoidal site, in Barcelona, on Cerda’s urban grid. So how does the concept of megaform respond to the dense urban grid of Barcelona? Horizontality, as one of the distinctive characteristics of a megaform, arises in the works of Frampton, along with the densification of the urban fabric.2

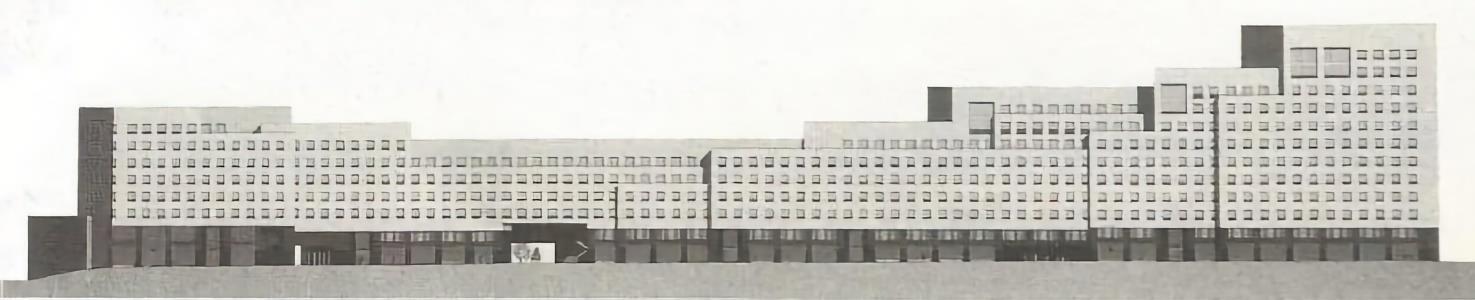

This is evident form the strategy employed by the architects which aimed at using the architecture to contribute to the city-building, through exploiting the Diagonal’s potential. Hence, the site was re-interpreted as fullness, as a fully constructed surface, instead of being treated as an empty site to be filled with a whole series of isolated towers and other built spaces. The project in its entirety is understood to be just another piece of the city’s grid because of the strange perimeter of the block. While the proposal’s dominating horizontality, with 300m length facing the street gives it a character of being a megaform, it also guarantees the continuity of the urban fabric through being built along the Diagonal Through the reversing the concept of ‘fullness of plot’, the proposal is instead perceived against emptiness The fullness is conceptually fulfilled through the continuity of pedestrian movement through the block. The void is interpreted and accepted as an element of the urban public realm. The image of the building is reflected in its empty space which reinforces and enhances its public status. The attention given to its proportion, measurements and construction through the manipulation of rhythm, distances and scales is evident in its architecture. In order to avoid the horizontality and scale of the block from being perceived as an undifferentiated mass, the architects used the notion of fragmentation and segmentation in dealing with the floorplan and the profile.3

1Frampton, K 1999

2Ibid.

3https://rafaelmoneo.com/en/projects/lilla-diagonal-2/

The building is attentive to what is unique and specific, thus disregards the concepts of symmetry and regularity by fully embracing the nature of the grid. The way it can be read from the street, from the broad sidewalks underlines the vital role of tangential perspectives. The building portrays the power of horizontality in regional identity while creating a sense of topography through its staggered façade The large size of the megaform allows us not only to accommodate various programmes under one roof, but also to generate their anticipatory nature which in its turn allows for them to be future-proof and gain the ability to change over time through housing varied functions. The 300,000sqm project encompasses various functions such as Shopping center, Convention center, Hotel and Offices, creating an interior urbanity that is similar to the concept of ‘a city within a city’, that liberates architecture from belonging to one architect, one actor and finds new ways to accommodate the collective. This also leads to the making and reshaping of urban public spaces, that are civic in character, which belong to everyone and yet nobody in particular.4

The staggered treatment of the façade creates a texture along the length of the block, subtly breaking the monotony while creating hierarchy and layering of planes iv This shows us how the notion of a megaform can be looked at in dense urban conditions, where the form does not fight against the pre-existing grid of the city but becomes an integral part of, juxtaposing itself in such a way that it establishes a strong relationship between the idea of size and integration.

Image credits: http://www.tag-am.net/10-lilla-diagonal-en

Orientation, grid, bigness and geography

Baker House Dormitory, Alvar Aalto, Cambridge, MA

The question of how this concept of integration works at different scale, with the theory of horizontality, of bigness that extends itself in a regular grid, along the shoreline can be analyzed through looking at the Baker House Dormitory, designed by Alvar Aalto Aalto’s pre-occupation of re-defining the place of the individual in modern society in the face of industrialization and urbanization through re-defining the modern notion of mass housing was reflected in his proposal for the dormitory built in 1946, facing the Charles River waterfront. In an attempt to maximize the view of the river for every student, the building imitates the way a curving snake slithers, while following a formal strategy. Some of the early sketches by Aalto show clusters of rooms facing south and, because a simple single-sided slab would not contain sufficient rooms, several ways of increasing the density: by parallel blocks in echelon, by fan-shaped ends, and by the "giant gentle polygon" resolving itself into a sinuous curve, that was finally adopted.5 The building's undulating form does not restrict the views of the rooms to be oriented at right angles towards the busy street The form of the building establishes a wide variety of room shapes, creating a wide variety of 43 rooms and 22 different room shapes per floor A composite curve with a single-loaded corridor, there was a lot of importance given to the orientation of the rooms in order to achieve the best view of the river, due to which the rooms on the western end were enlarged and created into large double and triple rooms, which had a dual orientation, receiving both the northern and western light.

The power of the morphology to address the landscape while having typology and the function as its mode of interrogation, the Baker House dormitory embodies the idea of bigness As per Frampton notion, it can be perceived as a complex form that cannot be necessarily articulated into a series of structural or mechanical subsets. It also inflects the existing urban landscape as it creates a sequence of spaces that address and establish a relationship with the landscape, the street as well as the waterfront. The building follows the “head and tail” pattern, a recognized device in Aalto’s buildings. The ‘head’ contains the principal space and the tail contains the subsidiary spaces.6At Baker House, the tail is much larger than the head which houses the rectangular dining and meeting area, yet the relationship is still apparent due to the use of more refined materials in the head compared with the brick-clad backdrop of the tail. This can be illustrated by a quote from Rossi that Colquhoun also mentioned in the ‘Superblock’ essay: ‘What is specific about a building is less its exclusive adaptation to particular functions than its capacity for representing ideas’ 7 It can be argued that the Baker House has more of a representative character that is more expressive, thus shifting functionalism away from the technical sphere and into that of humanism and psychology. The creative spatial expression is rooted into an economic rigour, where the wave in Aalto’s compositions symbolizes the functional heart of the building and the regularised spaces of the service areas.

7 Colquhoun (1981)

The issue of relating form with the function is addressed through the notion of ‘flexiblestandardization’, in which a unit of space may expand towards the light, rooted in a rectilinear, pedal, base

The inspiration lying at the heart of nature, biology offers a luxury of forms that are constructed with the same tissues, where the same cellular structures can produce millions of combinations.8 The abstract nature of this concept brings us back to its representational quality as a residential typology.

In an attempt at articulating his search for an elastic system for orchestrating growth, the spatial cells of which the Baker House is comprised of, are determined by the smallest unit required in the design brief, being the single, double and triple study bedrooms. These units are allowed to flex in a serpentine form. The distinctive fan-shaped form lead to variations of the undulating surface expression of sinuosity, and often, there is an underlying organizing geometry behind the undulating curve It has been argued in the past that his work has a sense of discontinuity and incompletion which echoes the essential nature of the human condition, also becoming the appeal of Aalto’s work.9(Antony Radford & Tarkko Oksala) But these recurring patterns of discontinuity span along the length of the block in such a way that ends up intensifying the urban fabric through its form.

Giedion establishes a relationship of the early modernist’s ambitions with the dormitory by observing that the “bedrooms and workrooms were as small as possible without destroying the vitality of the atmosphere.”10 The form of the building establishes extension by establishing new kind of continuities which adds to its character of a mega-structure where one could argue that it can be perceived as a large frame in which ‘all the functions of a city or a part of a city are housed' combined with the notion of 'citiesin-miniature’11

8Sarah Menin (2003)

9Antony Radford & Tarkko Oksala

10Giedion, S (1941)

11 Frampton (1999)