6 minute read

Glaciers and Ancient Lemont

Long ago, glacial ice advanced and retreated over thousands of years, the glaciers acting like giant scoops, driving and piling soil and rock, and carving the landscape into ridges and rings called moraines. This process left behind the unique hills, ravines, and stone and sand deposits that form Lemont today.

When the ice melted, the waters collected into a glacial basin east of a moraine and created a continental divide. Geologists called that basin ancient Lake Chicago. Eventually, two breaks in the moraine found outlets and the basin drained, becoming a smaller lake—Lake Michigan. The two outlets became the Des Plaines River Valley and the Sag Valley. Between these two valleys was an area of high ground, named Mount Forest Island, at the eastern edge of Lemont.

Today Mount Forest Island is a triangular section of land that extends from approximately Kean Avenue west to Route 83, from 107th Street on the south to the Des Plaines River on the north. Much of this area is now Cook County Forest Preserves.

The meeting of waterways at the tip of Mount Forest Island in Lemont later became crucial to westward expansion across the entire United States, providing transportation routes that connected the east and west coasts.

The Potawatomi and Settlement of Lemont

It is not certain how long Native Americans populated the area that became Lemont, but evidence exists that it could be as long as five to six thousand years. A succession of tribes occupied the area, most prominently the Illini. The Potawatomi inhabited Lemont Township as settlement approached.

The Potawatomi had a semi-migratory culture. This meant they lived and farmed in welldeveloped homes and villages in the summer, but left their summer homes for temporary winter camps, where they hunted and fished, following the food supply. They returned to their summer homes, much as “snow-birders” do today.

There were no permanent non-native settlers in the Lemont area prior to the 1830s, but French missionaries and explorers, such as Marquette and Jolliet, explored this area as early as 1673. Fur traders had traveled the rivers and land, and the English established a fur trade with the Indians. Illinois became part of the Northwest Territory of the new United States after the Revolutionary War. This brought early frontiersmen, speculators, merchants, and squatters. These people came from the Eastern States and immigrated from Europe. They were anxious to be the first to see and stake claims on the new land as statehood approached.

When Illinois became a state in 1818, the majority of the population lived downstate. Much needed to be done before homes, farms, and towns could be established in Northern Illinois and the Lemont area. The Potawatomi had to agree to give up their land. Land could not be purchased from the government until it was measured and defined. Settlement only made sense if goods could be transported to populations that wanted to purchase them, but there was no transportation through the wilderness. Knowing that settlement was inevitable, plans began long before the first settlers arrived.

These plans included treaties with the Potawatomi, surveying of the land, the development of supply routes, and planning of a canal to provide for transportation of goods. Lemont, a critical geographic juncture, became a key location.

The survey of Lemont was completed by 1827. In 1833, Indian tribes signed the Treaty of Chicago and agreed to relocate west of the Mississippi River. Most of the native population left by 1840, but some stayed. Today it is reported that Chicago has the third-largest urban Indian population in the United States, with more than 65,000 Native Americans in the greater metropolitan area.

The first known settler in Lemont was “Mr. Kinney” in 1830, followed by Jeremiah Luther in 1833, and William Derby and Orange Chauncey in 1834. They settled on a cluster of farms in the southeastern sections of Lemont Township, where the land was mostly flat and had rich topsoil.

One early settler was Joshua Bell. Joshua Bell was born in Coot Hill, Caven, Ireland on December 28,

1791. He immigrated to Canada in 1819, arrived in Lemont in 1838, and purchased land near what is now Bell Road and McCarthy Road. In addition to his farm, he established in the same area the Sag Bridge Inn, a general store, a tavern, and a post office. Joshua sold the store and tavern in 1844 and moved to Chicago, but his descendants remained on the Lemont farm for generations.

The Illinois and Michigan Canal

But from Lemont there was still no way to transport what was produced on farms to a market for profit. Waterways were the best option at that time, so plans went ahead to construct the Illinois and Michigan Canal, the canal that was suggested by Father Marquette in 1673. A canal here would make Chicago a major transportation hub, and Lemont farms and businesses would flourish.

In 1673, Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and his partner Louis Jolliet, a fur trader, explored this area. They were told by the Potawatomi who lived here of a route to Lake Michigan by way of the Des Plaines River. Traveling east and north on the Des Plaines, they came to a swampy area called Mud Lake that connected, except for a short portage, to the Chicago River, and from there into Lake Michigan. Having proved that it was possible to travel from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, the explorers realized that a canal between the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers would provide a water route from there to the Illinois River and then into the Mississippi and the Gulf. Branches of the Mississippi flowed throughout the western continent. A canal would open the entire North American interior.

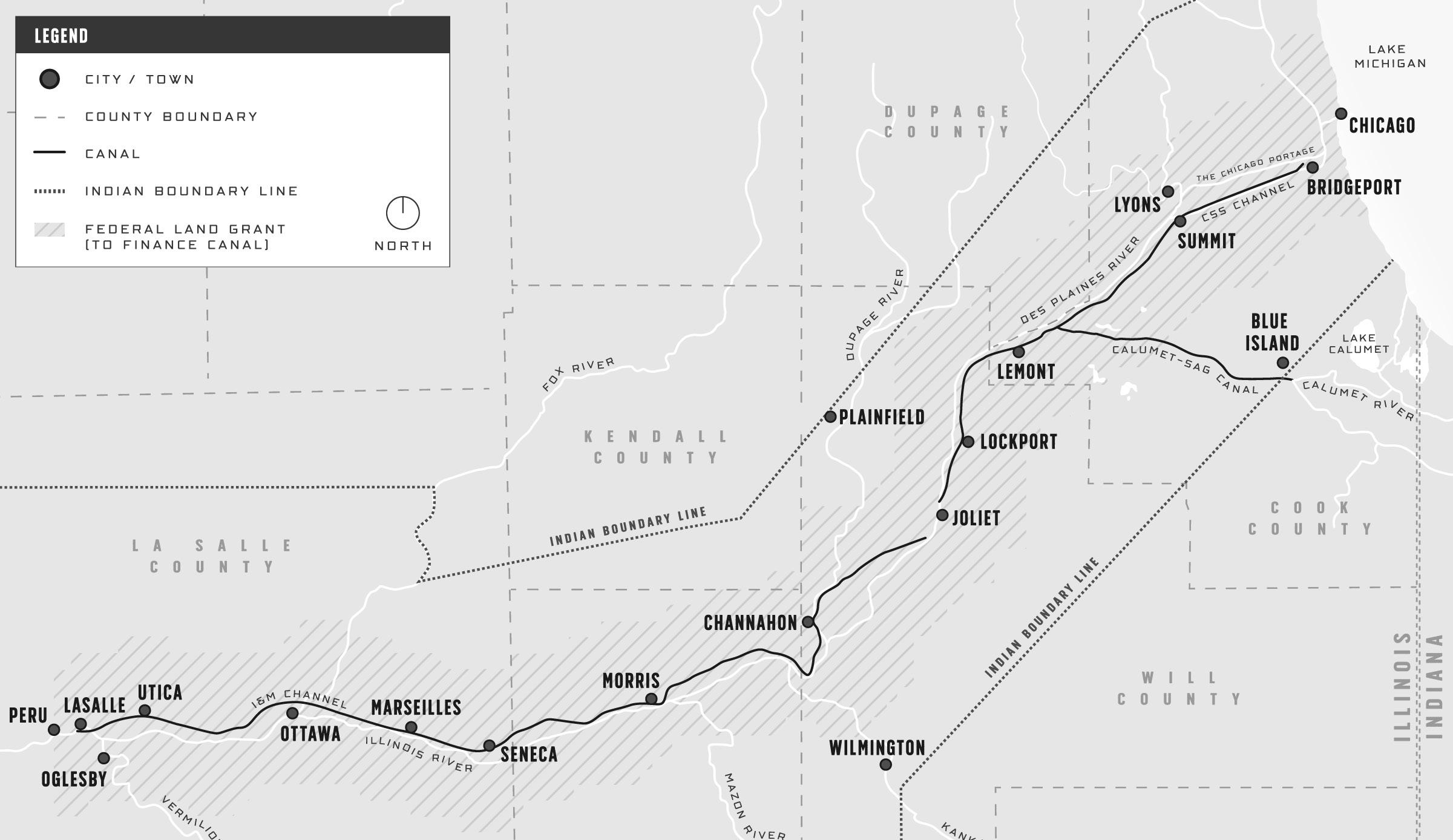

The United States government had long planned to build the canal, but it was not until 1822 that its construction was authorized by Congress. After a series of delays to capitalize the project and develop supply routes, construction began in 1836. The Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal that connected the Illinois River to Lake Michigan was not completed until 1848.

Lemont was a primary location on the canal. Not only did the canal run through Lemont, but along it was an ancient Indian trail that ran all the way from Joliet to Lake Michigan on the south side of the planned route, with no need to cross any waters. This trail was improved to become the major supply route for the canal and named for the canal’s main engineer, William Beaty Archer. It survives today as Archer Avenue.

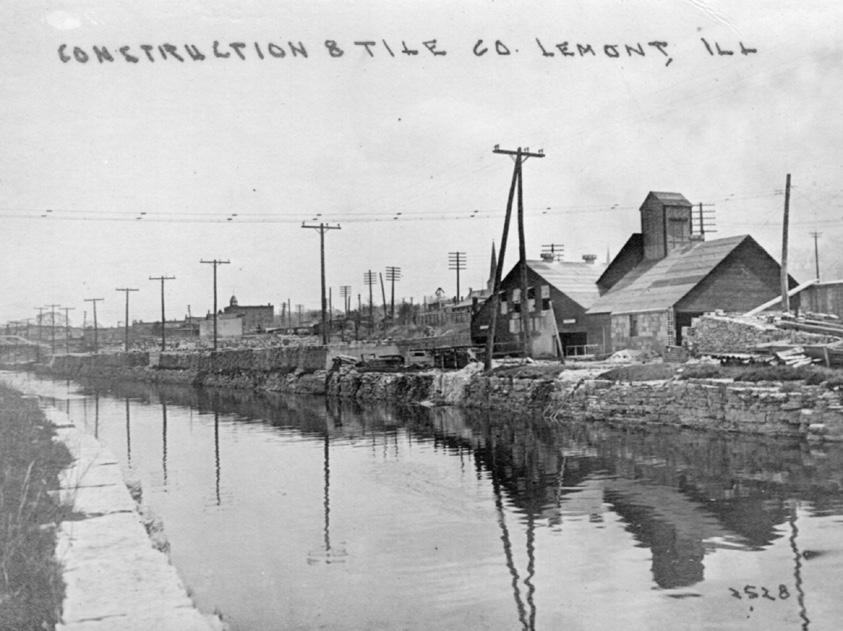

The completed canal opened in 1848, running from the Chicago River to LaSalle, Illinois. Muledrawn canal boats and barges carried cargoes such as lumber, grain, corn, and stone. They also carried passengers and their belongings.

Prior to the canal’s opening, in 1840 Lemont’s population was 2,107 and the city of Chicago’s population was just twice that, 4,470. Due to the canal, by 1850, the population of Chicago jumped to 29,963, and ten years later, in 1860, it had dramatically grown to 112,172 and had become a major industrial center.

Today the I&M Canal has become the nation’s first National Heritage Corridor, providing recreational and educational purposes. The canal no longer carries traffic, except for I&M Canal Boat Tours at LaSalle, Illinois.

Lemont Stone and Quarries

The need for unskilled labor on the canal had brought foreign immigrants to Lemont, many from Ireland, who wished to remain in the area once the canal was finished. Because the project was always short on funds, many of the workers had been paid not in cash but in “land scrip,” a voucher that allowed the worker to purchase land along the canal. Some bought parcels for farms, others bought bottom lands and stony bluffs, where an attractive stone had been discovered during the digging of the canal. Thus was born Lemont’s quarry industry. Soon wealthy quarry owners sold cut building stone so popular that the Sears Catalog at one time advertised a paint color called “Lemont Stone.”

The stone discovered in Lemont was quality building stone because it had a smooth appearance, occurred in layers thick enough to cut in blocks, had a crushing force that allowed for high weightbearing walls, and had a pale buff color that aged beautifully. With an abundance of labor experienced in cutting stone from the building of the canal and the proximity of the canal for cheap shipping to nearby Chicago, Lemont stone became highly desirable and profitable. Chicago’s famous Water Tower, Holy Name Cathedral, and the Old State Capitol Building in Springfield, Illinois were built with Lemont stone.

Quarries were in operation in Lemont from the 1830s until the early 1900s, when other building materials became favored. It is estimated that at one time as many as fifty quarries were in operation between Lemont and Joliet. With the closing of the quarries, pumping of runoff and spring waters ceased, and the quarries filled, leaving behind Lemont’s picturesque recreational area, the Heritage Quarries. Today an adventure park, The Forge, offers climbing, zip-lining, entertainment, and other recreational activities.