Beliefs and Customs through the Ages in Newry and Mourne

Exhibition at Newry and Mourne Museum

12th September 2011 – 13th May 2012

Artist’s impression of the Cistercian abbey at Newry as it may have appeared c.1300

© Newry and Mourne Museum (artwork by Philip Armstrong)

Front cover:

Kilnasaggart Pillar Stone, County Armagh

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce)

Réamhrá an Mhéara

Ba mhaith liom an leabhrán seo a mholadh, leabhrán a ghabhann le Nósanna agus Deasghnátha fríd na hAoiseanna i gCeantar an Iúir agus Mhúrn. Is é seo taispeántas sealadach in Iarsmalann an Iúir agus Mhúrn.

Tugann an taispeántas léargas de nósanna agus dheasghnátha a bhaineann leis an réigiún seo. Leagann an taispeántas béim ar a dteacht chun cinn thar na haoiseanna, ó thréimhse Neoiliteach go dtí an lá atá inniu ann, agus an dóigh a mhúnlaigh na leasaithe seo saol na ndaoine agus ár dtimpeallacht.

Chomh maith leis sin tugann an taispeántas deis don Iarsmalann, fairsinge déantán agus doiciméad ina cnuasach a bhaineann le nósanna agus le deasghnátha, a nochtadh.

Chuaigh an Iarsmalann i dteagmháil le roinnt mhaith d’eaglaisí an cheantair, grúpaí áitiúla,agus iarsmalanna eile a thug ábhar tábhachtach ar iasacht don taispeántas atá muid thar a bheith sásta a thaispeáint i ngailearaí sealadach nua.

Ba mhaith liom mo bhuíochas a ghabháil le foireann na hIarsmalainne as a gcuid oibre agus le hachan duine a thug eolas, déantáin agus grianghrafanna don taispeáint seo.

Comhairleoir Séarlaí Ó Cathasaigh Méara Chomhairle an Iúir agus Mhúrn

Mayor’s Foreword

I would like to commend this booklet which accompanies Beliefs and Customs through the Ages in Newry and Mourne, a temporary exhibition at Newry and Mourne Museum.

The exhibition provides an overview of the beliefs and associated customs in this region. Their evolution over the centuries is highlighted in the display, from the Neolithic period to the present, and how these changes have shaped our lives, and our landscape.

The exhibition also provides an opportunity for the Museum to showcase the breadth of artefacts and documents relating to beliefs and customs in its collection.

The Museum engaged with many local churches, local groups and other museums who have contributed loans of important material to the exhibition, which we are proud to display in the new temporary exhibition gallery.

I would like to thank the staff of the Museum for their work and thank all who contributed information, artefacts, and photographs to this exhibition.

Councillor Charlie Casey Mayor, Newry and Mourne District Council

Beliefs and Customs in Prehistory

There has been human habitation in Ireland for 9,000 years, but it is only from the Neolithic period (4000 –2500 BC) that archaeologists have found some evidence of beliefs and customs. Known as the first farmers, Neolithic people built megalithic tombs.

Excavation of these tombs provides insight into burial customs of the period and some archaeologists believe that the tombs were also ritual centres celebrating solar and lunar events. This may be reflected by the commanding position of the passage tomb on the summit of Slieve Gullion.

The evidence for beliefs and customs is richer and more varied in the Bronze Age (2000 BC -500 BC). Burial customs changed, with human remains placed in a pit or stone lined cist. Monuments of this period such as stone circles, henges, standing stones and rock art have been interpreted as possibly having some ritual or astronomical significance.

The ritual deposition of metal objects, human remains and animal bones in lakes and rivers in the middle Bronze Age and continuing into the Iron Age, may indicate a type of water cult. These objects have been found in the King’s Stable, a man-made pool, and Loughnashade Lake, both near Navan Fort. It has been speculated that the origins of some of the holy wells of the Early Christian period may date back to these water cults.

Navan Fort was the Emain Macha of the Ulster Cycle stories and was a major Iron Age ritual and royal centre.

These stories portray the legendary heroes of Ulster such as CúChulainn, who had pagan beliefs and looked to druids, a priestly caste, for divination and advice. Tales such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley), portray druids as sorcerers opposed to the coming of Christianity.

The druids were also associated with the rituals that accompanied the four sacred festivals that demarcated the seasonal changes; Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasa and Samhain Aspects of these festivals were later Christianised, for example the spring festival of Imbolc on the 1st and 2nd of February was associated with the pagan goddess Brigit. This became the feast day of Saint Brigid, whose birthplace was Faughart near Dundalk.

Over millennia, a rich oral tradition developed around prehistoric monuments. This folklore was collected in south Armagh by T.G.F. Paterson and Michael J. Murphy, and in south Down by E. Estyn Evans and Michael G. Crawford, representing a vibrant legacy of the beliefs and customs of the past.

Clontygora Court Tomb, County Armagh

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce) Known locally as The King’s Ring, the tomb was excavated in 1937 and small fragments of bone, pottery and flint tools discovered. The King’s Ring was a grand place once, but they took stones to build the lock on the Newry Canal…There’s times when there’s music in the ring. It’s quare music altogether. One minute it wud coax the heart out of ye, an’ the nixt it would frighten ye with the sorra that is in it. …’ From Country Cracks by T.G.F. Paterson (Dundalk, 1945)

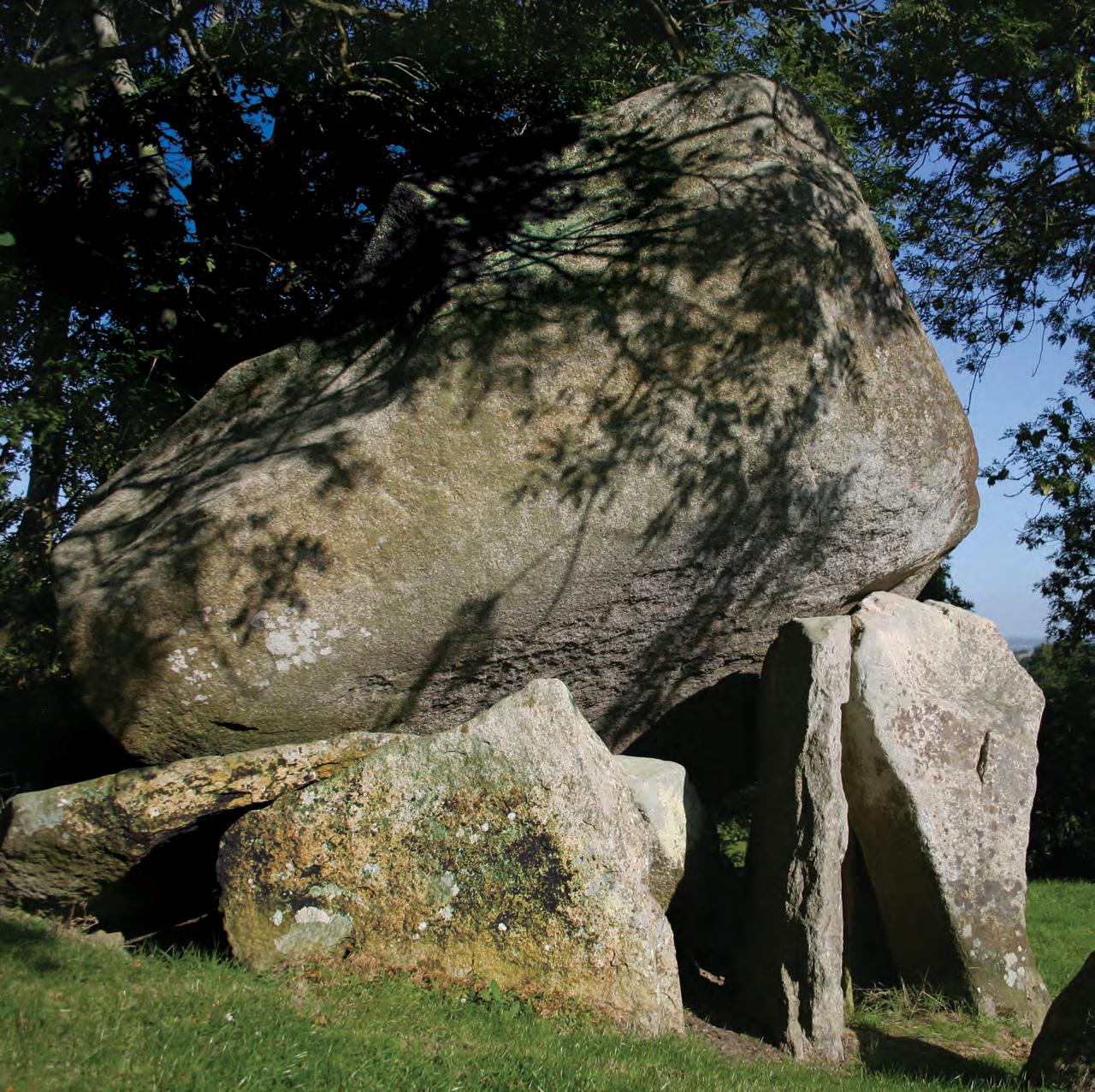

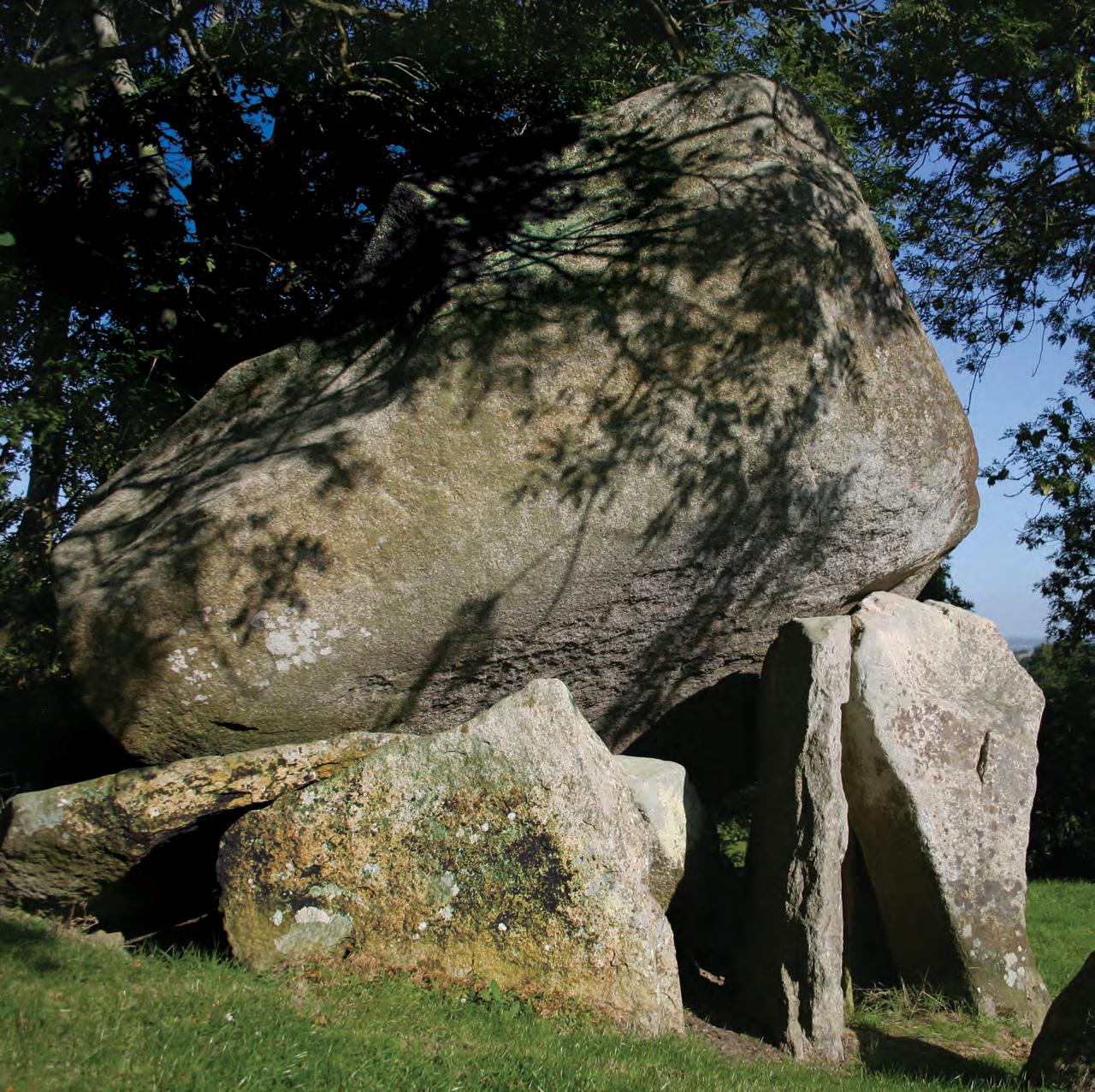

Goward Portal Tomb, County Armagh

Near Hilltown, in the foothills of the Mourne Mountains. The enormous capstone of the tomb has slipped from its original position and would have roofed the rectangular chamber. Investigations in the first half of the 19th century uncovered a cremation pottery vessel and a flint arrowhead. Known as Finn McCool’s Fingerstone, local tradition recorded by E. Estyn Evans relates that Finn threw the capstone from Spelga and that he sleeps underneath.

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce)

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce)

The Coming of Christianity

Little is known about how Christianity first arrived in Ireland. The first missionaries may have come from Gaul (France) in the 4th and 5th centuries but their work was superseded from the late 5th century onwards by the mission of Patrick, the son of an official in Roman Britain.

Much of the work of St. Patrick was focused on northeast Ireland and 7th century source material links him with south Down in particular. A strong local tradition records St. Patrick with the planting of a yew tree ‘at the head of the strand’ above the Clanrye River which gave Newry its name – Iubhair Cinn Tragh. This is mentioned in the Annals of the Four Masters.

Early Christian mission activity was probably very localised with royal patronage playing a major role. Scholars have suggested that place-names with domnach [donagh] may indicate early missionary centres. Donaghmore, near Newry, may have been the ‘mother church’ for evangelising the area known as Mágh Cobha, the plain which gave its name to the Uí Echach Cobo, the ruling dynasty of west Ulaid (west County Down, later the Diocese of Dromore).

During the 6th to 8th centuries a number of other important ecclesiastical settlements were established in the Newry and Mourne area, often under the patronage of dynamic and well-connected individuals. In the 6th century, a church was founded by St. Bronagh of Glenn Sechis at Kilbroney on the north shore of Carlingford Lough and c.700 AD, an ecclesiastical centre was established at Kilnasaggart by

‘Ternoc son of Ceran Bic under the patronage of Peter the Apostle’.

Old Town Seal

Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Local tradition credits St. Patrick with the planting of a yew tree ‘at the head of the strand’ above the Clanrye River which gave Newry its name – Iubhair Cinn Tragh. Recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters, this may indicate St. Patrick adapting pagan tree cults to Christianity. As evergreens, yew trees symbolise the eternal cycle of life, death, transformation, regeneration and rebirth.

One of the most important early convents in Ulster was established at Killevy, near Slieve Gullion, in the late 5th or early 6th century by St. Moninne (also known as Darerca, daughter of Erc). Like St. Patrick, a ‘cult’ emerged in honour of St. Moninne from the 7th century onwards. A number of ‘lives’ of St. Moninne were written and she was celebrated in two hymns composed at Killevy in the 8th century.

The Irish Church underwent significant reform in the 12th century. One result of this was the introduction of new European monastic orders. Around this time Killevy was converted to the Augustinian order and, in 1153, a Cistercian abbey was founded at Newry. A parish structure developed, with parish churches being built, such as the old churches at Kilkeel and Greencastle.

Donaghmore Parish Church and High Cross, County Down © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) The high cross, carved with images from the Old and New Testaments, dates from the 10th – 11th centuries. The present church opened in 1741 with the tower and chancel being added in 1828 and 1878 respectively.

Donaghmore Parish Church and High Cross, County Down © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) The high cross, carved with images from the Old and New Testaments, dates from the 10th – 11th centuries. The present church opened in 1741 with the tower and chancel being added in 1828 and 1878 respectively.

Reformation and Consolidation

Originally a theological and doctrinal challenge to the late medieval Catholic Church, the 16th century European Reformation soon became enmeshed in politics and the ambitions of secular rulers. The beginnings of the Reformation in England and Ireland were associated with Henry VIII’s break with the papacy in 1536. In Ireland, the Reformation became associated with Tudor expansion, particularly during the reign of Elizabeth I.

The dissolution of the monasteries was the first aspect of the Reformation to affect the Newry area. In 1542, the last abbess of the Augustinian convent at Killevy, Alicia Negan McDonnechy O’Hanlon, withdrew with her nuns and the convent with its lands passed into secular control. This period also saw the dissolution of the Cistercian abbey at Newry and, in 1552, the abbey and its lands were granted to Sir Nicholas Bagenal, a settler from Staffordshire. Bagenal was one of the New English reformers and he saw the establishment of the Protestant religion as part of English plantation in the south Down area. In 1578 he built St. Patrick’s Parish Church in Newry, which was the first purpose-built Protestant church in Ireland.

The religious profile of Ulster, however, changed with the arrival of Scottish Presbyterians during the plantation in the early 17th century. Presbyterian congregations began to be established in Ulster from the 1640s. A Presbyterian congregation may have been established at Newry around this time under the Rev. James Simpson. Although this growth was curtailed after the Restoration of Charles II

in 1660, Presbyterians and other Non-Conformists were given greater freedom by William III. This led to the establishment of the Synod of Ulster and the Toleration Act of 1719.

The Old English and Gaelic Irish remained Catholic as they associated Protestantism with an alien government. Periodic repression of Catholic worship and freedom intensified after the defeat of the Catholic James II by the Protestant William III in 1690 and the first Penal Laws were passed in 1695. This legislation placed further limitations on Catholic freedom in religious and secular life.

By the mid 18th century Newry had become a thriving commercial port. International contact with the outside world introduced various Protestant denominations. The spread of Methodism, the system of religious belief promoted by John and Charles Wesley, is one example. During his preaching tours of Ireland, John Wesley made sixteen visits to Newry between 1756 and 1789 preaching to large congregations of Catholics and Protestants.

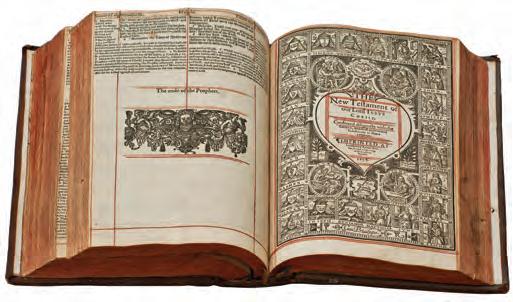

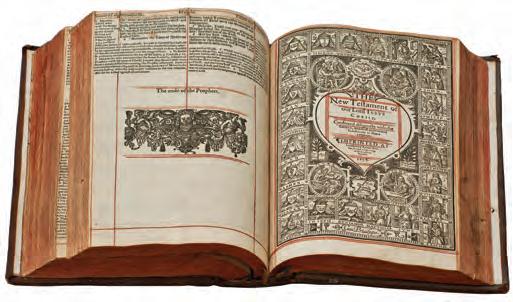

Geneva Bible (Breeches Bible)

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) This was one of the most important translations of the Bible to be made as a result of the Protestant Reformation. This copy, printed in 1608, was presented to St. Patrick’s Parish Church in Newry by the fourth Earl of Kilmorey in October 1920.

A Mass House was built on this site c.1730 and the oldest grave dates from 1763. The present church was built in 1789 and served as a cathedral before the present cathedral was opened in Hill Street in 1829.

St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Chapel Street, Newry

© William McAlpine

St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Chapel Street, Newry

© William McAlpine

Revival and Transformation

Revival in all denominations continued in the 19th century with developments sometimes being influenced by political events. After the Act of Union of 1801 the political power of the Church of Ireland was diminished in a series of reforms as its privileged position was resented by other denominations. The 1861 Irish Census had revealed that 4.5 million people were Catholic, 700,000 were Church of Ireland, while 550,000 belonged to other denominations, mostly Presbyterian. The Irish Church Act of 1869 placed all denominations on the same standing.

The Catholic Relief Acts of the last quarter of the 18th century had repealed most of the penal laws against Catholics, but still excluded election to Parliament and to major office. This barrier was lifted with the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 and ushered in a new confidence, which was locally reflected by the opening of churches and convents. In Newry the Cathedral of St. Patrick and St. Colman was opened in 1829, followed by Saint Clare’s Convent in High Street in 1830.

Changes in the wider Presbyterian Church impacted on the Newry congregation during the ministry of the Rev. John Mitchel. Differences in aspects of doctrine between conservative and liberal elements led to division. Mitchel was a supporter of the liberal Presbyterian view and, with

his congregation, withdrew from the jurisdiction of the General Synod in 1829. This led to the building of new Presbyterian churches throughout the district.

The Evangelical Revival of 1859, which started in the parish of Connor in County Antrim, is also closely associated with the Presbyterian community in Ulster. These developments led to a revival in personal faith, and the establishment of Sunday Schools and support for the temperance movement.

Temperance, the control of alcoholic consumption, was promoted by all denominations in Ireland. One of the best known figures associated with this movement was Father Theobald Mathew who visited Newry in August 1840 where he addressed a gathering in Hyde Market.

During the 20th century Protestantism experienced a growth in evangelical denominations, particularly in the post-war period. Fundamental changes in Catholic worship were ushered in by the Second Vatican Council (1962 – 1965) including the end of the Latin Mass and change in layout of the altar.

European integration in the latter half of the 20th century facilitated the migration of people from other countries, who have settled in this region. Some of them have different beliefs systems, which has contributed to a more multicultural society.

Taylor’s Illustrated Manuscript Bible

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) Inspired by the Evangelical Revival, James Taylor took one year and seven months to make this copy of the King James Version of the Bible.

Contributors

A number of people have been invited to contribute articles to this booklet to provide a deeper insight to topics and processes involved in this exhibition. The contributors are:

Christina Joyce

Christina is a visual artist and teacher, who lives in the Mournes. She has a Masters Degree from the National College of Art & Design, Dublin. During her MA in Art in the Digital World, she examined the symbolism of religious statues of the 1950s. She is interested in storytelling, folklore, nature, and social history among many other things.

Kevin Murphy

Kevin is a native of south Armagh and was a teacher of English and Politics for thirty-six years. He has coauthored the books Kick Any Stone and A Famine Link - The Hannah. He has researched a number of topics and is best known for his work on Michael J. Murphy, Ribbonism, Townlands, the 1798 Rebellion and the Famine.

Sean Madden

Sean is a conservator of works of art and archive on paper. He qualified in 1995 from the University of Northumberland (Newcastle upon Tyne) with a MA degree in Conservation of Works of Art and Archive on Paper. In 1998 he established a full-time private conservation business. He has been the paper conservator for Special Collections at University of Sheffield since 1996.

Nuala Maguire

Nuala is an Objects Conservator who qualified from Cardiff University in 1998 with a degree in Archaeological Conservation. She has been freelance since 2008 and has worked with a range of national and local museums. She is also a qualified designer and keen seamstress with an interest in other textile crafts.

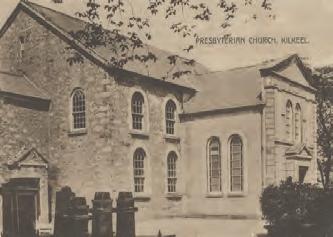

Postcards showing churches in Kilkeel, County Down, in the first half of the 20th century

From The Hugh Irvine Collection at Newry and Mourne Museum

John Wesley’s Pulpit, Old Meeting House Green, Newry

© The National Library of Ireland

Local tradition records that John Wesley used this pulpit, (which still survived in the ruins of the First Presbyterian Church in the late 19th century), during his visits to Newry in the 18th century. The church on the Old Meeting House Green was built in 1722 after Presbyterian worship was legalised by the Toleration Act in 1719.

Gospel Hall, Glennane, County Armagh

© Michael O’Connell

Gospel halls have been a feature of the Ulster countryside for many years. This example was built in 1923 using corrugated iron. Biblical texts are displayed on the porch. It was demolished and a new gospel hall erected on the site in 2001.

Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church, John Mitchel Place, Newry

© William McAlpine

Built as a result of the split in the Presbyterian Church in Newry after the Second Non-Subscription Controversy. The Meeting House in High Street continued to be used by the Non-Subscribing congregation. Subsequently a new site was obtained in Needham Place (later John Mitchel Place) and the present church erected to the design of the architect, W.J. Barre, in 1853.

Built in 1816, this is an example of a pre-Emancipation chapel. Like many Catholic churches of this period, it has a T-plan with internal galleries, which are approached from the outside. The architecture is Gothic in style.

St Malachy’s Roman Catholic Church, Camlough, County Armagh. © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

St Malachy’s Roman Catholic Church, Camlough, County Armagh. © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

A Photographic Pilgrimage

Christina Joyce

Commissioned by Newry and Mourne Museum in summer 2010, Christina spent six months photographing subjects associated with beliefs and customs in south Down and south Armagh.

The Newry and Mourne area has a high concentration of historical sites across a landscape dominated by uplands. Finding sites and photographing them opened my eyes to the wealth of history on my doorstep. Increasingly, the pilgrims whose footsteps I followed became real to me. I hope that my photographs inspire a similar response in the viewer. The following meditations are shared with this intention.

Time stands still on mountain tops. They are more resistant to human activity. Standing at the mouth of Cailleach Beara’s House and surveying the Ring of Gullion and beyond, one is transported back in time 4,000 years to the Neolithic people who built this tomb, or to 1789 when locals disturbed the chamber searching for a witch.

To pause at the cairn on Knockshee, between the High Mournes and Carlingford Lough, and to breathe the heathery-salty breeze, is to feel reverence for the dignitary who rests here.

Kilbroney small cross has endured centuries of weather. Lamplight reveals its endearing face, demonstrating the sculptor’s playful artistry. At dawn, at dusk or by moonlight many sites have an ethereal presence. Viewing

the full moon at Ballymacdermott Court Tomb, modern life seems to dissolve into mist.

A vibrant holly tree has brightened a sombre Rathfriland cemetery for two hundred years or more. Like many indigenous species, holly’s associations in folklore and history links us to the distant past. A Rag Tree at St Moninne’s Well, preserves a timeless tradition of prayer. A lone Haw at Ballykeel Dolmen seems ineffably rooted in the history of the site.

I was privileged to be able to photograph Irish Wolfhounds. Watching the lithe hounds at Annaghmare, it seemed that their warrior owners were not far away. I read accounts of local saints I had never heard of, St Thuan, St Domangard, St Tighernach, St Moninne, and St Mahula, influential members of their society who caused me to re-imagine this landscape.

My journey started at a forgotten court tomb near my home. I wondered about the nameless person buried there and was impelled to find out more. My photographs aim to stimulate curiosity about the past. The more I scratch the surface, the more I realise what lies beneath and the more admiration I feel for our predecessors.

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph Christina Joyce)

Locally known as Calliagh Berra’s House, Calliagh Berra was a mythical old hag or witch and local folklore relates her adventures with Finn McCool.

“Do ye know her house on the mountain an’ the lake beside it. Shure it was into that very lake she coaxed fool Finn. An’ in he went fresh an’ youthful an’ out he come a done oul’ man.” T.G.F. Paterson, Armagh Miscellanea Vol. XII.

A

Rag trees are often associated with holy wells which have ‘cures’ for ailments. A nearby tree or bush would often be festooned with rags, Rosary Beads and other religious tokens, perpetuating prayer.

View from Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb (South Cairn), County Armagh

Rag Tree at St Moninne’s Well, near Killevy Churches, County Armagh © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph Christina Joyce)

View from Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb (South Cairn), County Armagh

Rag Tree at St Moninne’s Well, near Killevy Churches, County Armagh © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph Christina Joyce)

Michael J. Murphy‘The Last Druid of Sliabh Gullion’ [Benedict Kiely] Kevin Murphy

Michael J. Murphy, writer and folklorist, was born in Eden Street, Liverpool, in June 1913. Both of his parents were from the parish of Dromintee, south Armagh, and when he was nine years old the family returned home.

He attended the local national school until he was thirteen years old and he then went to work as a half-acrown-a-day labourer with neighbouring farmers.

Michael’s father, also Michael, and his mother Mary Campbell, were accomplished storytellers. Michael senior, a seaman, was a friend of both James Connolly and Jim Larkin and was a strong socialist and republican. So it was no accident that the young farm labourer developed an interest in folklore, customs, the plight of the rural poor and the political problems of a divided country. Living in the shadow of Sliabh Gullion gave him an appreciation of landscape and of the mystic quality of his environment.

He began in the early 1930s collecting stories from the people around Dromintee, writing articles and short stories for newspapers and magazines, doing broadcasts for Radio Eireann and the BBC. When his first book

At Slieve Gullion’s Foot was published by Harry Tempest of Dun Dealgan Press in 1941 he joined the Folklore Commission in Dublin as a part-time collector. He continued to work as a farm labourer, freelance writer

and part-time collector of folklore for most of the 1940s. In 1949 he became a full-time collector and moved with his wife Alice and young family to Glenhull, Co. Tyrone. Further work for the Folklore Commission brought him to the Glens of Antrim, Rathlin Island, the Mournes, Cavan, Fermanagh, Louth, Monaghan and back to south Armagh.

He compiled, until his retirement in 1983, what is probably the largest collection of oral tradition by a single individual in the English-speaking world. These one hundred and fifty volumes are in University College, Dublin. Each volume has between three hundred and fifty and seven hundred pages. He kept a journal to accompany the material and compiled an invaluable glossary of Anglo-Irish speech.

Michael was also an accomplished creative writer and social commentator. He wrote six plays; a collection of prose poems; a large number of social and political articles and more than fifty short stories.

He died at Walterstown, Castlebellingham, County Louth, on May 18th 1996 and is buried, along with Alice, in Darver cemetery.

Michael J. Murphy with his wife Alice and sons Patrick and Michael Jnr. c.1949 © Department of Irish Folklore, University College Dublin

Michael J. Murphy with his wife Alice and sons Patrick and Michael Jnr. c.1949 © Department of Irish Folklore, University College Dublin

Conservation treatment

drawings of St Mary’s

Sean Madden

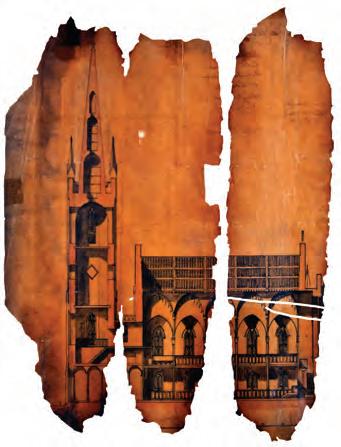

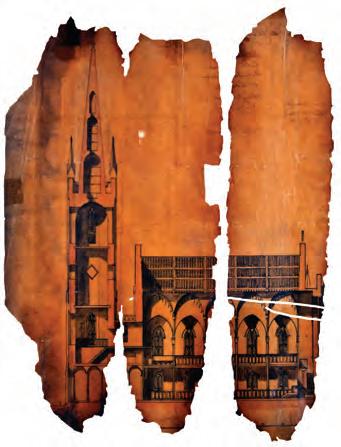

Sean was commissioned by Newry and Mourne Museum in 2010, with grant aid from the Northern Ireland Museums Council, to conserve and prepare for exhibition a series of fire damaged drawings of St. Mary’s parish church in Newry. These are from the Reside Collection.

The drawings consisted of charred fragments of original ink and water colour plans on tracing paper. The plans had been damaged by fire in the 1950s and then had been rolled for storage.

Each drawing was surface cleaned to remove loose surface dirt and mould spores. Old cello-tape and adhesive residues used to carry out repairs were removed using a scalpel and localised heat treatment.

Several oxidising metal particles were located in the paper fibre of the drawings using ultra violet light, these were removed under magnification using a tungsten needle.

All of the drawings were flattened by being pressed between archival blotting paper under weighted perspex for eight weeks. This treatment removed the ‘memory’ of being rolled. Old tears and structural damages were repaired using Japanese paper (Kizuki -shi) and non-aqueous Klucel G adhesive.

Each drawing was then attached by it’s edges only, to a Japanese paper backing. This held the drawings flat and prevented the drawings from recoiling, allowing mounting onto conservation board. Only the Japanese backing paper was adhered to the board while the drawings hung free.

Michael J. Murphy (1913 – 1996)

© The Arts Council of Northern Ireland

Once the drawings had been unrolled they were found to be many fragments which had become very dry and brittle. They comprised seven incomplete drawings, all severely damaged. The fire had caused significant loss, scorching, and dehydration to the paper fibre, exacerbating the already weakened paper structure. Poor storage and handling over the years had caused a heavy build up of surface dirt and mould spores. Insects, water and old repairs (including the use of cello-tape) had also damaged the drawings.

After a full conservation survey of the drawings the conservation treatment commenced with the aim of preserving the drawings, carrying out restoration where ethically appropriate, and mounting and framing the drawings for exhibition.

The drawings were then mounted with conservation card window mount and sealed into new oak frames.

I found the conservation of these drawings a rewarding challenge. I had to use well tried techniques as well as innovating new procedures due to the fragile state of the drawings and the complexity of the damage from a number of sources.

I am proud with the finished result as it signifies what conservation of historic artefacts should be, preserving the past for the future.

Drawings of St. Mary’s Parish Church after conservation These drawings date c.1900 and are from the Reside Collection

Interior of St. Mary’s Parish Church, Newry © William McAlpine Building of St. Mary’s Parish Church commenced in 1810 to a design by Patrick O’ Farrell under the supervision of the architect, Thomas Duff. The church was consecrated on 25th August 1819.

Drawings of St. Mary’s Parish Church after conservation These drawings date c.1900 and are from the Reside Collection

Interior of St. Mary’s Parish Church, Newry © William McAlpine Building of St. Mary’s Parish Church commenced in 1810 to a design by Patrick O’ Farrell under the supervision of the architect, Thomas Duff. The church was consecrated on 25th August 1819.

Conserving textile and other items for Beliefs and Customs Exhibition Nuala Maguire

Nuala was commissioned by Newry and Mourne Museum in 2011, with grant aid from the Northern Ireland Museums Council, to conserve and prepare a range of items for display in this exhibition.

A number of textile items were conserved including a 1930s First Communion dress, an 1880s sampler and christening robes.

Marble model of Newry Cathedral

Different kinds of plaster and glue on the surface of the model showed it had been repaired several times in its history. These were removed by using small tools to lift the residues without scratching the marble. Solvents were used to remove old yellowed glues and pieces which had become separate were reattached using a conservation adhesive.

The missing areas were filled in, then painted to tone in with the colour of the marble. Wax was applied to the surface to seal and improve the appearance of old scratches. The wooden base had several large scratches and areas of loss. These were sealed and again painted to tone in with the main colour of the base.

Model of the Cathedral of St. Patrick and St. Colman, Newry

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

The model was made by the Toman brothers who lived in Francis Street, Newry. It depicts the cathedral as it appeared at the turn of the 20th century, before the transepts, bell tower and sanctuary were added. The model is very detailed, and the interior includes the altar, rows of seats and pillars.

Wedding dress

The dress was cleaned using a museum vacuum which has a much lower suction than domestic vacuum cleaners. A soft brush was used to loosen dirt from the surface.

Dirt particles can be sharp and can cut through delicate fabrics.

Areas where the silk was torn or lost were supported using fine silk netting and thread, as this supports the weight of the tear and prevents further damage to weak areas. A loose silk decoration to the waist area was reattached to the dress to prevent loss.

The dress has been mounted on a mannequin, (the mannequin used is child size) this gives you an idea of how people’s shape has changed over time. Polyester wadding was used to build up the chest and hips of the torso whilst leaving a small waist, this would have been achieved by the owner wearing a corset.

Wedding dress

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

Purchased in 1914 in Fosters drapery store, Newry, the silk and lace wedding dress has a matching pair of silk shoes. It belonged to Ella McGaffin who became Mrs Poland.

© Newry and Mourne Museum

This dress was also worn by Patricia’s sisters. It has been conserved for this exhibition.

Photograph of Patricia McArdle wearing her First Communion dress mid 1930s

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the staff of Newry and Mourne Museum for their assistance in this booklet:

Joanne Cummins

Emma Farrell

Conor Keenan

Shane McGivern

Maureen O’Connell-Fitzpatrick

Frances Potts

We are grateful to Christina Joyce, Kevin Murphy, Sean Madden and Nuala Maguire for contributing articles to this booklet.

Thanks also to Northern Ireland Museums Council for grant aid to conserve items in this exhibition.

Thanks to all those who contributed to the exhibition through donations, loans or expertise, including:

• Irwin Major and St Patrick’s Church of Ireland

• Fr. Gerard Fearon and Fr. Noel McKeown, St Catherine’s, Dominican Church

• Christina Joyce

• Jack Gamble

• Justyna McCabe

• Fr. Stanislaw Hajkowski

• Sean Madden

• Kevin Murphy

• Margaret McGaffin

• Greer Ramsey and Sean Bardon, Armagh County Museum

• Nuala Maguire.

• Michael O’Connell • Fr. Hackett, Kilbroney • Cathy Brooks

• Seamus Mac Dhaibheid

• Ursula Mhic An tSaor

• Michelle Boyle

• Andrew Kernaghan

• Sister Perpetua, Sisters of Mercy Convent, Newry

• Phillip Armstrong

• National Museums Northern Ireland

Text by Noreen Cunningham, Dr. Ken Abraham and Declan Carroll

Poster advertising a visit to the Town Hall in Newry by Ballymacarrett No. 1 Salvation Army Band in 1923 © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) This band had just returned from performing at the London Festivals at the Alexandra Palace and Albert Hall.

Salvation Army Citadel, Trevor Hill, Newry © William McAlpine

Formerly known as the Ebenezer Chapel, it was erected in 1816 as a meeting house for Congregationalists. There was originally a school at the rear of the building. The Salvation Army moved into the chapel in 1908.

Picture of Emmanuel Chapel Convent of Mercy, Newry © Sisters of Mercy, Newry

The Emmanuel Chapel in the Covent in Catherine Street is named in the honour Sarah Russell later Sister Emmanuel, sister of Lord Russell of Killowen. She was elected Superior of the Convent of Mercy in 1870. The chapel was designed by John Brown and built by Denis Neary, both from Newry and opened in 1901.

©

All

Published by: Newry and Mourne Museum Bagenal’s Castle Castle Street Newry Co. Down BT34 2DA www.bagenalscastle.com

Copyright 2011

rights reserved Newry and Mourne Museum Design: G. Watters

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce)

© Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by Christina Joyce)

Donaghmore Parish Church and High Cross, County Down © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) The high cross, carved with images from the Old and New Testaments, dates from the 10th – 11th centuries. The present church opened in 1741 with the tower and chancel being added in 1828 and 1878 respectively.

Donaghmore Parish Church and High Cross, County Down © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine) The high cross, carved with images from the Old and New Testaments, dates from the 10th – 11th centuries. The present church opened in 1741 with the tower and chancel being added in 1828 and 1878 respectively.

St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Chapel Street, Newry

© William McAlpine

St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Chapel Street, Newry

© William McAlpine

St Malachy’s Roman Catholic Church, Camlough, County Armagh. © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

St Malachy’s Roman Catholic Church, Camlough, County Armagh. © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph by William McAlpine)

View from Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb (South Cairn), County Armagh

Rag Tree at St Moninne’s Well, near Killevy Churches, County Armagh © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph Christina Joyce)

View from Slieve Gullion Passage Tomb (South Cairn), County Armagh

Rag Tree at St Moninne’s Well, near Killevy Churches, County Armagh © Newry and Mourne Museum (photograph Christina Joyce)

Michael J. Murphy with his wife Alice and sons Patrick and Michael Jnr. c.1949 © Department of Irish Folklore, University College Dublin

Michael J. Murphy with his wife Alice and sons Patrick and Michael Jnr. c.1949 © Department of Irish Folklore, University College Dublin

Drawings of St. Mary’s Parish Church after conservation These drawings date c.1900 and are from the Reside Collection

Interior of St. Mary’s Parish Church, Newry © William McAlpine Building of St. Mary’s Parish Church commenced in 1810 to a design by Patrick O’ Farrell under the supervision of the architect, Thomas Duff. The church was consecrated on 25th August 1819.

Drawings of St. Mary’s Parish Church after conservation These drawings date c.1900 and are from the Reside Collection

Interior of St. Mary’s Parish Church, Newry © William McAlpine Building of St. Mary’s Parish Church commenced in 1810 to a design by Patrick O’ Farrell under the supervision of the architect, Thomas Duff. The church was consecrated on 25th August 1819.