28 minute read

4. Overall Evaluation of VOICES through Situational Analysis

by VOICES

4.1 Introduction 4.2 Method

The study of multi-faceted interventions like VOICES, that aim to intervene on various aspects of already complex systems, such as the provision of health and social care for people experiencing multiple disadvantage, requires advanced methodologies to understand the potential impact on the target population’s health, well-being, and on health equity [8]. Situational Analysis is a methodology designed to unpick the knowledge from complex inquiries, where methodologies grounded in linear models of cause and effect are inappropriate [6]. It is well-suited to this purpose for several reasons. First, data can be gathered using various methods, such as reports, interviews, field notes and minutes [7]. Second, emerged from Grounded Theory, it is an iterative and data driven methodology, where data collection in each phase depends on the findings from the previous phase. This is appropriate as we are not testing predefined hypotheses but are being guided by the data [9]. Third, Situational Analysis is one of the few complex systems methodologies that places the importance of context at the heart of its investigation [9] . Specifically, Situational Analysis involves a three-stage methodology of conceptual maps, which aims to provide a detailed picture of non-linear interlinkage of complex systems structures and processes that shape the experiences of those within a specific environment [7] . The three stages are:

Advertisement

Micro level analysis on situational maps is implemented where all important human, nonhuman, elements of the situation under concern unfold (reported in section 4.3).

Meso level analysis involves the production of social worlds/arenas maps, where all collective actors (humans) and actants (non-humans) are analysed in relation to the arena in which they are engaged and negotiated the related to situation discourses (reported in section 4.4).

Macro level analysis uses positional maps to unpack all positions that have emerged from data around key discourses or issues. These positions are presented on a

Cartesian map in which axes present the issues of concern or controversy [8, 27] (reported in section 4.5). Through this bottom-up, data driven methodology, Situational Analysis produces a higher and abstract level of explanation of non-linear relationships within the context (or situation) of interest. The Situational Analysis process is iterative. There are no fixed boundaries between the three analytical stages. Data collection of each phase depends on the findings of the previous one, but there is a constant recursive analytical loop (where earlier stages can be amended based findings from subsequent stages) until the saturation of evidence is achieved. For the overall exploration of VOICES’ impact and legacy, Situational Analysis was chosen as linearity, universality and generalisability are not relevant. Rather, post-modern ideas that embrace fragmentation, instability, diversity, context, and positionalities (all accepted by Situational Analysis) are necessary. When taking this approach, nothing was taken for granted; especially on issues that seem ‘normal’ within the situation and, therefore, have become invisible. Minor discourses or issues are given equal consideration as those that appear to be major or more prominent, because they may be indicative of power imbalances. Similarly, deviations from the norm are not treated as exceptions but as the boundaries

of the situation. Finally, a thorough investigation is used to identify all relevant actors/ actants (including those that are usually hidden, silenced, or only discursively/tangentially present) as they might help to improve our understanding of the situation. For this project, Situational Analysis focused on the three priority areas through which VOICES aimed to affect systems change:

Ensuring fair access to services. Housing First Stoke-on-Trent. Making service users leaders in service design and commissioning.

Data sources were primarily from existing material, including completed and on-going VOICES discrete reports (including those summarised in Section 2), previous interviews and case studies, field notes, and minutes of meetings (see Appendix 1 for list of data sources).

Following processes set out by Clarke [27], after thoroughly reading all written materials, the first stage of analysis was to create situational maps. The analytic focus of the situational map is the situation. In this case, the situation was the wider system of support for people in Stoke-on-Trent who experience multiple disadvantage. Initially, various ‘messy’ situational maps were produced and included all human (i.e., key people, groups, networks, organisations) and non-human elements of the situation (i.e., physical infrastructure, resources, policies, discourses). To produce a readable map different colours have been used to indicate different categories of elements (Appendix 2). The messy map was then used to create an ordered map, which arranged all elements into categories (Appendix 3). This helped to identify ‘major issues/ debates’ and ‘related discourses’ that were most relevant to situation (e.g., “coproduction”, “stigma and marginalization”, “equity and healthcare provision”) and were later used to focus the Situational Analysis. Subsequently, three situational relational maps were created, one for each of the three VOICES priorities (Appendices 4-6). These maps are used to show relationships between the elements of interest and other elements in the situation, in a systematic and coherent way. These maps were used to generate questions that were explored in three workshops (one for each priority area). These workshops helped to further understand the relationships between key elements and significant discourses/issues, leading to the next phase of Situational Analysis.

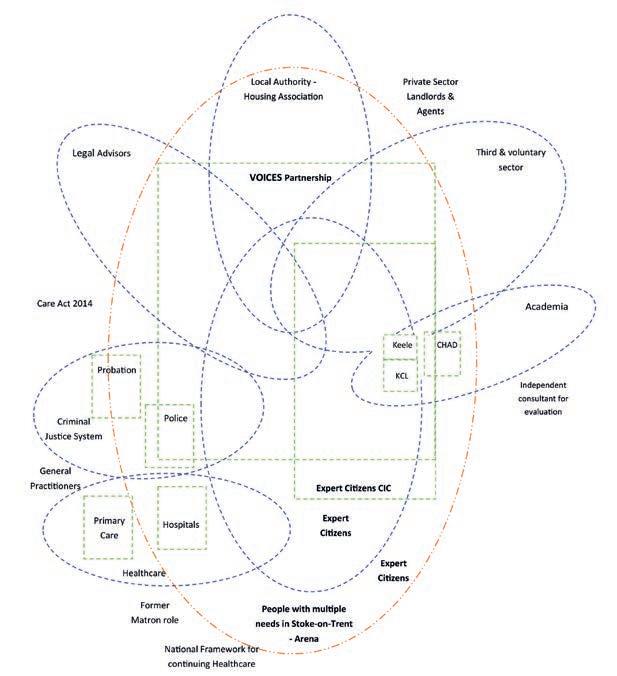

The meso level of analysis began with the creation of the social worlds/arenas map (Figure 2). This map represents the key social active players (social worlds), and the field (arena) in which they interact; for example, how the social worlds of local voluntary and public sector organisations interact within the arena of the

local support system for people in Stoke-on-Trent who experience multiple disadvantage. In this sense, social worlds are comprised by various social entities and institutions, all with their own perspective and collective identity at the present time, within the situation of inquiry, and are dynamic, potentially changing over time[8] .

Through Situational Analysis, we attempted to understand the boundaries of the social worlds, as well as their collective actions and interactions with each other (i.e., their negotiations, collaborations, conflicts, seeking of power). The final product is a map of “relational ecological form of organizational analysis dealing with how meaning making, and commitments are organized and reorganized again and again over

time” [27, p150] .

In the map, social worlds that are similar are positioned adjacent to each other, and those with conflicting or opposing relationships are positioned opposite. The depth of intersections indicates the extent of their single or cooperative involvement with the situation. Finally, the actor(s) or actant(s) identified as important from the data, but which are not part of a collective action, are shown in the social worlds/arena maps without a surrounding circle [27] .

In the social worlds/arena map for this evaluation, people from Stoke-on-Trent who currently experience multiple disadvantage were defined as the arena in which all the actions, negotiations, conflicts, debates and so on, took place. Within this arena, 10 different social worlds were identified, five of which comprised the VOICES partnership (and, therefore, intersect the large green square that represents the VOICES organisation): 5 social worlds identified and comprising the VOICES organisation

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

Third sector housing associations that support housing needs Voluntary sector champions who support those who need and use health care services Local public sector agencies, mostly derived from the City Council (e.g., Housing, MaRG) and the NHS Legal advisers’ social world, which is dominated by the third sector welfare advisers Expert Citizens social world, acting as ambassadors of local people with lived experience on multiple disadvantage.

In the map, social worlds that are similar are positioned adjacent to each other, and those with conflicting or have opposing relationships are positioned opposite. The depth of intersections indicates the extent of their single or cooperative involvement with the situation. Finally, the actor(s) or actant(s) identified as important from the data, but which are not part of a collective action, are shown in the social worlds/arena maps without a surrounding circle.

The other five social worlds aligned closely with VOICES objectives (while not being part of the VOICES partnership) such as legislation, criminal justice system, healthcare sector, Department for Work and Pensions and Academia. Nine out of 10 social worlds actively, collaborated, competed and/or conflicted with one another, while one was identified only discursively. The visual representation of the VOICES partnership in Figure 2 shows the complexity of the situation, but also illustrates how VOICES provided the common ground for many organisations to work towards widely accepted targets regarding the tackling of multiple disadvantage. This helped to overcome competitive attitudes and practices from partnerships of voluntary and public sectors.

Figure 2. Social worlds / Arenas map

The positional maps in section 4.5 present the main findings. However, there are several aspects of the social world/ arenas map to note, as they are important it the development of the analysis. First, a pinnacle of the VOICES legacy captured in the social worlds/arena is the evolution of Expert Citizens. Expert Citizens have transformed from a group of people with lived experience of multiple disadvantage without collective action, to a Community Interest Company (CIC) that is independent of VOICES and holds equal positioning among the other social worlds within the arena (of supporting people experiencing multiple disadvantage in Stoke-on-Trent). This power-seeking relationship of Expert Citizen’s relative to the other VOICES partnership organisations (as identified from narratives and workshops with Expert Citizens) was presented by positioning Expert Citizen’s social world opposite to voluntary and public sector.

The map also illustrates the emergence of Expert Citizens as a new social world that started to interact autonomously with the other social worlds and the situation, with potential for sustainable impact through affecting the wider system of support for people experiencing multiple disadvantage. The Expert’s Citizens social world is positioned slightly opposite the public sector healthcare social world, mainly due to Expert Citizens’ involvement in the primary care report and the identification of the gatekeeping role of local GP practices to people experiencing multiple disadvantage when trying to access them. However, Expert Citizen’s social world is adjacent to voluntary sector champions and Academia as where both social worlds collaborated with Expert Citizen’s for various VOICES reports/evaluations. Expert Citizens’ social world takes the largest part of the VOICES partnership organisation to indicate the extent of support that they have received from VOICES, to:

Develop as an autonomous organisational entity.

Emerge as co-designers, codeliverers and co-evaluators of various methodologies and tools that have been developed with VOICES (e.g.,

INSIGHT service evaluation,

Care Act toolkit). Second, legal advisors’ social world is positioned opposite public sector social worlds (specifically in relation to welfare benefit claims), but adjacent to Legislation social world, to reflect their role in promoting legal literacy. This is because the lack of legal literacy in the public sector emerged as a main barrier to people experiencing multiple disadvantage having fair access to benefits and welfare (to which they were entitled), and legal advisors offered a solution. Third, the criminal justice system, which includes organisations like the probation service and police, did not oppose any other social worlds. Despite the issues regarding inappropriate prison release plans or the initial resistance to incorporate specialist welfare benefits adviser within the probation service, there were positive changes throughout the period of VOICES. Indeed, this was true for all social worlds, especially Expert Citizens, except for the healthcare sector where a lack of engagement was observed.

Fourth, academia played a part, albeit a lesser one, mostly in trying to apply rigorous independent research and evaluation to study specific activities, projects or areas relevant to VOICES (as indicated in Section 2). An independent consultant who also supported VOICES evaluation process, though not part of Academia social world, also appeared adjacent to it. Finally, several ‘implicated actors’ (human) and ‘actants’ (non-human) were identified; elements that play an indirect role in the situation, but critically, did not appear to have done so before VOICES (i.e., their indirect involvement is part of the VOICES legacy). For example, private landlords and letting agents benefited through Housing First (through renting properties), but in some cases created problems (e.g., failing to maintain property quality standards). They are not presented as a social world because they did not act collectively. General Practitioners have often been reluctant to intervene (as reflected in Section 2.5), either through lack of understanding of their legal obligations, a belief that people experiencing multiple disadvantage are primarily a social care phenomenon, or because they are able to remain disengaged (which increases pressure on crisis healthcare services through failure to identify and treat health problems before they escalate). The implicated actants relating to the Legislation social world included legislation that governs how the public sector must support people facing multiple disadvantage (e.g., Care Act 2014, Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, National Framework for Continuing Health Care, Equality & inclusion strategy 201-2017). The important point here is that the public sector can lack knowledge regarding the legal rights of people experiencing multiple disadvantage, follow them reluctantly or partially/ not in the spirit of the law (e.g., as observed through primary care gatekeeping and hospital discharge reports).

4.5 Data collection and analysis: Main findings - Positional maps (Stage 3)

Drawing on the wealth of material considered, the final macro analysis reflects our best effort to elucidate and represent the various positions taken with respect to the major discourses/ issues. Again, where possible, we avoid naming specific individuals, groups, or organisations. The outcome is a number of positional maps, some generic and some specifically relating to the three priorities under investigation

4.5.1 Fair access to local support services of people experiencing multiple disadvantage

Within this priority area, five positional maps are presented to highlight the key discourses/ issues that create barriers to fair access and that VOICES’ work has attempted to address.

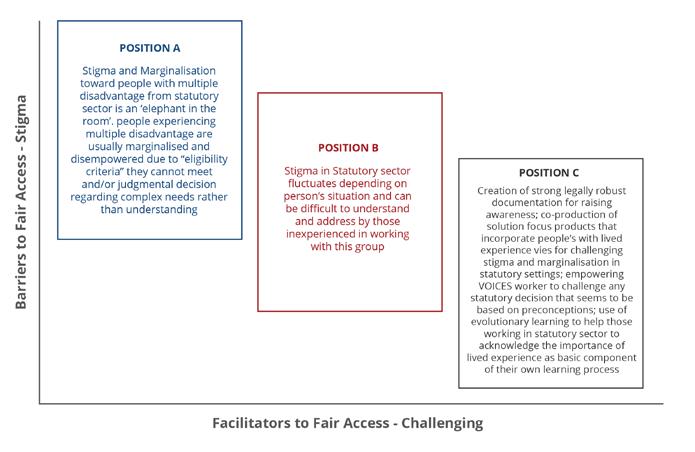

Stigma & Marginalisation

Figure 3 illustrates a fundamental barrier to people experiencing multiple disadvantage accessing services: stigma and marginalisation among some personnel in public sector support services. This is the first position (Position A) on the positional map that was identified in the data, and specifically in two different VOICES reports: a) Hospital discharge and homelessness and b) Primary care gatekeeper projects. It was also widely acknowledged during the workshops with stakeholders and Expert Citizens.

“I think probably the

elephant in the room is a little bit the stigma which gets attached to our

customer group at times”

McCormack, Parry and Gidlow [18]

Workshop discussions highlighted (Position B) that stigma can vary with the needs/situation of the individual presenting (e.g., different stigma attached to people with substance misuse issues vs. homeless vs. past offenders). This is not only problematic for the individuals seeking care/support, but also for staff who lack the knowledge and experience to deal effectively with potentially challenging behaviour or situations (as a result of their inexperience). This position found strong support among participating stakeholders. VOICES has made important moves to challenge this problem (Position C) through:

Producing legally informed materials and recommendations to raise awareness (e.g.,

Gatekeeper report on Primary care where through mystery shopping methodology raise awareness on the subject matter on national level).

Co-producing solution-focused products that challenge stigma and marginalisation, such as

VOICES and Expert Citizen’s coproduced methodologies (e.g.,

INSIGHT) and tool kits (e.g., Care

Act tool kits, MEH safeguarding).

These examined understanding among local organisations who work with people experiencing multiple disadvantage, and empowered VOICES to challenge any incorrect or unjust decisions.

Empowering and training public sector professionals to acknowledge the importance of lived experience as basic component of their own learning process.

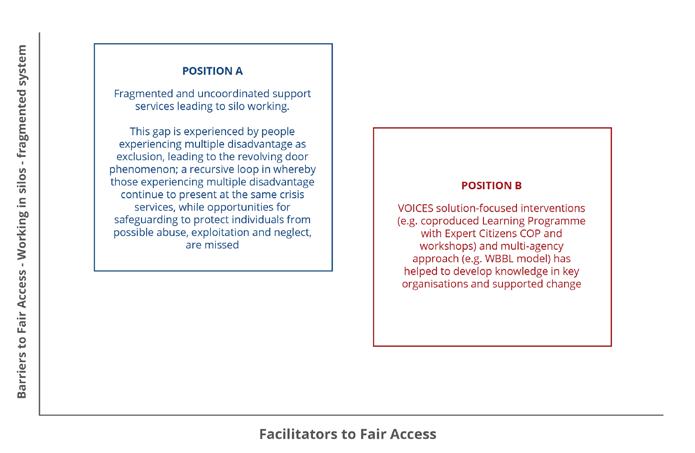

Silo Working

Figure 4 illustrates the common issue of silo working by organisations within a fragmented system of support services. Critically, the gaps between services/ organisations are experienced by people experiencing multiple disadvantage as exclusion. Silo working jeopardises effective coordination between services, which has the potential to avoid the “revolving door” phenomenon. To challenge this, VOICES developed a multi-agency approach and solution-focused interventions that have helped to develop knowledge in key organisations and supported changes in practice, such as codevelopment and co-production together with Expert Citizens of targeted Learning programmes and Community Of Practice workshops, and the incorporation of the specialist welfare benefits adviser within the frontline teams.

Figure 3. Positional map for stigma and marginalisation as a barrier to accessing services

Figure 4. Positional map for silo working as a barrier to accessing services

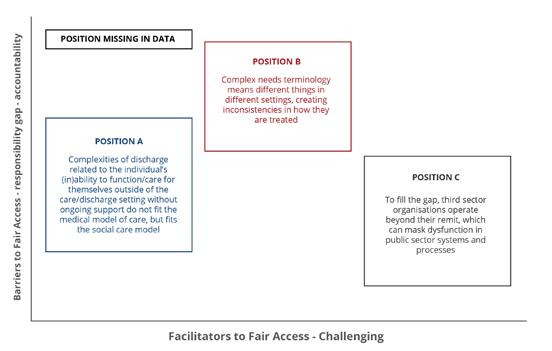

Responsibility and accountability gaps

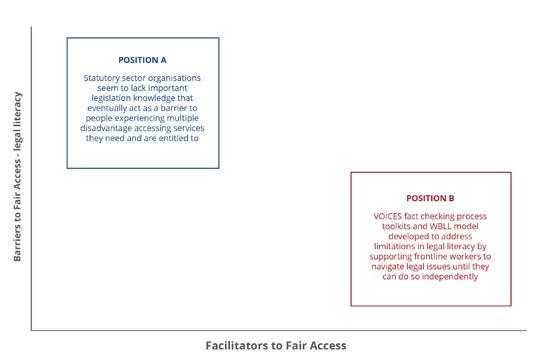

Figure 5 illustrates the issue of gaps in responsibility and accountability for supporting people experiencing multiple disadvantage, a likely consequence of a system fragmented by silo working. This is particularly important in the context of people exiting crisis services, such as hospitals, where there needs to be a clear understanding of each organisations’ legal responsibilities to ensure that the individuals transition between settings and who is responsible for each stage (e.g., Accident and Emergency, to local authority). As the Former Chair of the Faculty for Homeless and Inclusion Health acknowledged “long-term dispossession is fundamentally an issue of health” [28, p8] and, as such, requires a change in position from the health sector where it is generally considered to be the concern of housing and social care. VOICES reports have shown the large gaps in provision, in particular, between health and other services (as illustrated in Figure 5). The positional map highlights two strong positions found in the data: the notion that this is the responsibility of social care (position A); the other position that the third sector work beyond their remit to cover this gap, to the benefit of the individuals, but serving to mask a shortcoming in the system (position C). No position was found regarding the “taking of responsibility”, but one stakeholder identified potential for misunderstanding regarding the meaning of “multiple disadvantage” in different settings, and the need for better clarification (e.g., in healthcare settings this implies a need for multiple medical services vs. social care, where the meaning is more aligned with VOICES customers and their needs) Figure 6 shows the positional map relating to a lack of legal literacy, another common phenomenon that was largely unchallenged before VOICES. Position A shows the public sector apparently lacking knowledge of some important legislation, which acts as a serious barrier to people experiencing multiple disadvantage accessing the services they need and to which they are entitled. Often, frontline personnel are working with insufficient knowledge and or misunderstandings around policies, which are perpetuated as the policy. This can be considered a ‘negative feedback loop’, whereby organisations lack the incentive to address legal literacy problems in their staff. Doing so could mean having to dealing more situations, and potentially complex cases, perceived to be high demand with low chances of reward/positive outcomes. Therefore, managers pass on ‘myths’ and misunderstandings to frontline workers that, in turn, are enacted as policy. VOICES helped to address this problem through developing toolkits (e.g., Care Act toolkit) and models (e.g., WBLL) to facilitate development of related knowledge and skill in frontline staff (Position B).

Figure 5. Positional map for responsibility and accountability gaps as a barrier to accessing services

Figure 6. Positional map for legal literacy as a barrier to accessing services

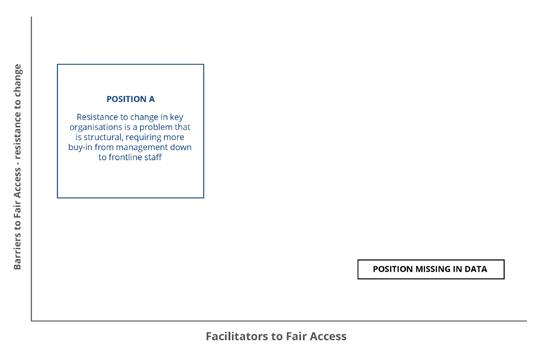

Figure 7 is the final Fair Access to Services positional map and relates to resistance to change, at both organisational and individual levels. Evidence, such as that presented in WBLL report and workshops undertaken for this analysis, highlighted a perception that key organisations can be reluctant to internal change their processes and ways of working. This issue was exemplified by the WBLL model (see 2.12). Having a specialist welfare advisor embedded in support services was a key proposal from VOICES, taking a multi-agency approach to provide free welfare/ benefit expertise to key partners (first within VOICES, then other services) to allow organisations to provide effective and legally informed financial advice and support to people experiencing multiple disadvantage. As Position A indicates, resistance to change was observed at personal/functional and structural (organisational) level. No position was found on how VOICES had systematically responded to such challenges. Some examples were given during the workshops, but these seemed more as a response to a given problem rather than well-planned solution focus approach. Resistance to change is a wellknown phenomenon in systems thinking and various solutions should be planned and tested at future similar attempts. Within this priority area, three positional maps are presented that illustrate the main discourses that emerged.

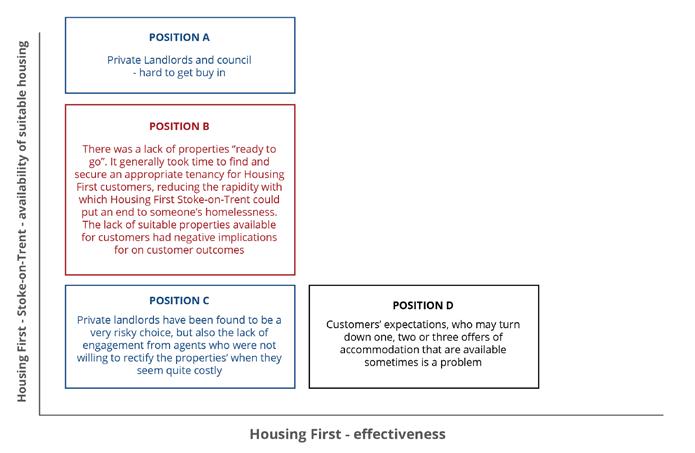

Availability of suitable housing

Figure 8 outlines the major discourse/issue and perennial challenge with Housing First in Stoke-on-Trent: limited availability of suitable housing. Positions A suggested that the biggest problem is the difficulty to secure both the social and council properties, and those of private landlords. Similarly, Position B indicates the general challenge of housing demand exceeding supply, leading to delays in securing appropriate tenancies for those referred to Housing First.

Another barrier shown through Position C was that the lack of social and council housing availability leading to a reliance on private landlords and letting agents, one of the biggest concerns. This position verified the importance given to these roles at the social worlds/arenas as implicated actors (as they could not be engaged, despite best efforts, through the Housing First evaluation).

what it says on the tin, you have got appropriate accommodation for somebody first and then you wrap support around them. Now if you haven’t got enough properties to begin with, that’s clearly

an issue, isn’t it?”

Gidlow et al [24]

Finally, Position D suggested that customer expectations were another type of barrier, with examples of customer who had refused two or three different accommodation offers. This neither violates Housing First principles nor suggests a mainstream behaviour of Housing First customers. Rather, it may indicate another issue that emerged from the Housing First evaluation regarding unsuitable accommodation (e.g., sub-standard, or unsuitable location). Unrealistic customer expectations were a position among some stakeholders and reported as such. However, the solution does not necessarily lie in addressing those expectations, but in addressing perceptions among the stakeholders regarding the Housing First model. This links back to the demand for appropriate properties (primarily single occupancy) leading to compromise, where customers might have to choose between accommodation that is not suitable (based on quality or location) or wait for suitable accommodation (perhaps in hostel or on the street).

Figure 8. Positional map for availability of suitable housing as a barrier to Housing First

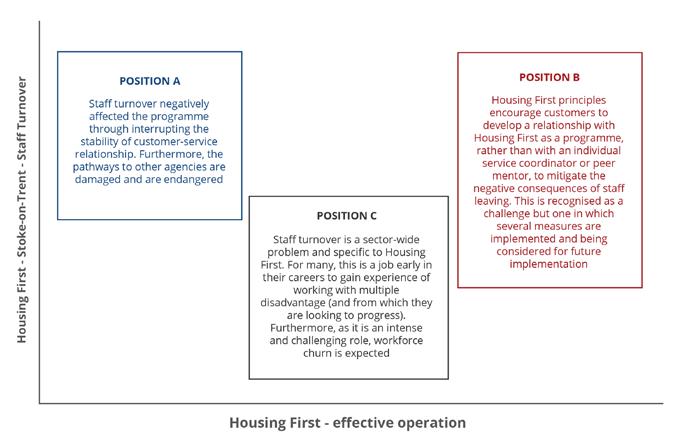

Figure 9 is the positional map relating to staff turnover. The frequency and negative implication of staff turnover in Housing First were a key issue. Three main positions were identified through the Housing First evaluation and related workshops. Position A notes the negative effects of high turnover through interrupting the continuity and stability of customers’ relationship with the service and, in turn, their engagement with other support services. Opposing this, Position B indicates the response to problems of staff turnover, which is inevitable and needs to be managed (rather than prevented). This stresses the need to encourage customers to develop good relationship with the program itself – rather than only their service coordinator or peer mentor (who might leave). Although this was recognised as a challenge, it is in keeping with Housing First principles and necessary for people experiencing homelessness who are likely to feel disengaged from and let down by services. Position C illustrates the position that high staff turnover is a sector-wide challenge and is not specific to Housing First. Two reasons identified were the high demands of the role and the development/ progression of workforce who might see frontline Housing First work as pathway in developing their own career.

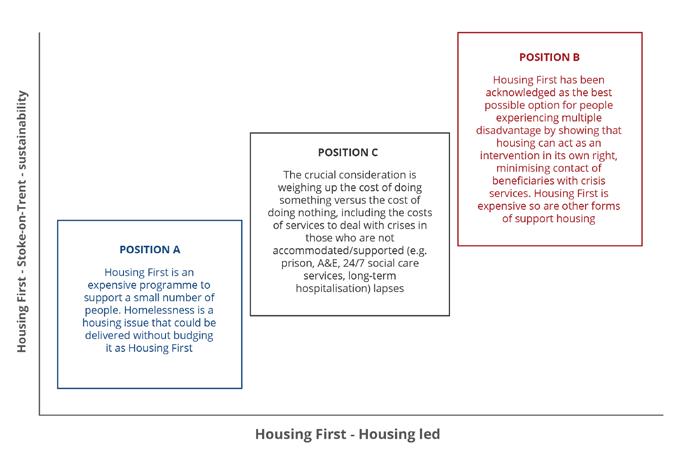

Sustainability of Housing First in Stoke-on-Trent

Figure 10 illustrates the final and most critical discourse regarding local systems change needed for a sustainable Housing First programme as a local strategy for tackling chronic homelessness, or a revised programme that adheres less rigidly to the Housing First principles but might be more readily accepted by key stakeholders. Three positions were verified from the data and workshops. Position A shows the wellknown argument that focuses on the cost of implementation. This view considers Housing First as a costly approach with a relatively small number of beneficiaries. It advocates for a less intense, housing-led intervention, which deviates from Housing First principles (e.g., finite support, greater for selection of customers, tenancy conditional on engagement with support services). In opposition, Position B expresses the need to maintain Housing First as the key strategy for people experiencing multiple disadvantage, especially after being acknowledged as the best possible option for this population and its approval by the VOICES Partnership Board (which includes a range of public/ third sector partners) to extend the programme for 12 months. This position acknowledges the high cost of running a Housing First programme but provides a counter argument that numerous other support services that are even more expensive. Position C uses the comparative principle, arguing that doing nothing costs more than doing something, and that effective intervention (even costly options) has wider benefits through avoiding the costs of dealing with the consequences of inaction (e.g., incarceration, emergency hospital care, 24/7 social care services).

Figure 9. Positional map for staff turnover as a barrier to Housing First

Figure 10. Positional map for programme sustainability as a barrier to Housing First

4.5.3 Making Service users leaders in service design and commissioning

The third VOICES priority area concerned the greater role for people with lived experience, who have:

These are the people with lived experience who, through VOICES, have become established within the political agenda and can be considered a key requirement for a systems change approach. Two positional maps are presented to illustrate key discourses/issues for this theme.

“Tasted at first-hand

how the system can progressively miss chances to help them or even

actively exclude them”

Project Plan, Fulfilling Lives Stoke p.7

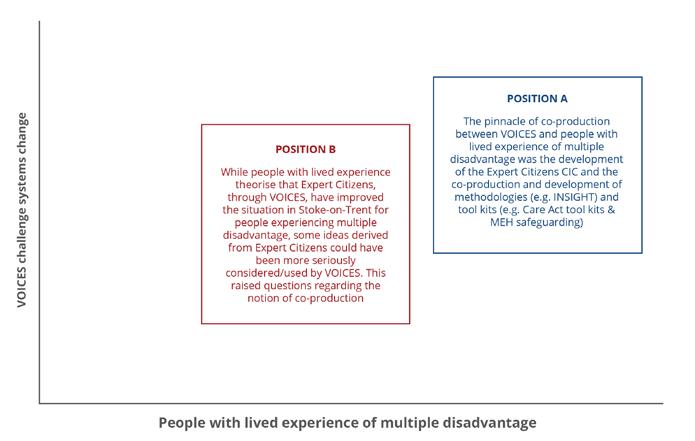

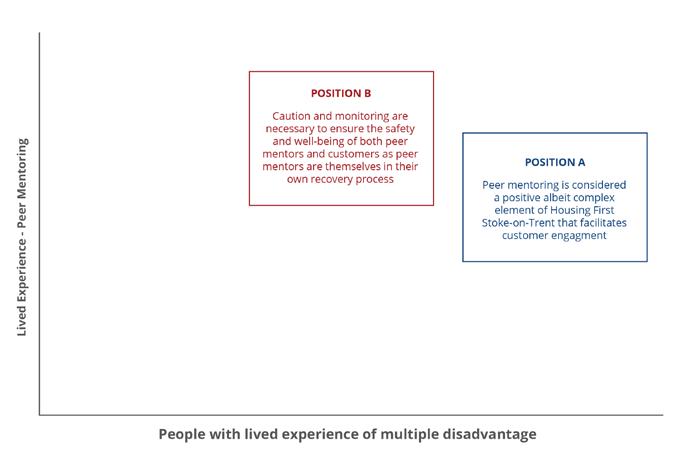

Development of Expert Citizens CIC

In Figure 11, which relates to the development of Expert Citizens CIC, Position A identified this as a cornerstone achievement of VOICES. It is the pinnacle of co-production between VOICES partnership and local people with lived experience, in addition to subsequent, and no less important co-development and co-production between VOICES and EC-CIC methodologies (e.g., INSIGHT) and tool kits (e.g., Care Act tool kits, MEH safeguarding). Position B stresses that, despite Expert Citizens have managed to improve the things in Stokeon-Trent, not all their ideas have been taken under serious consideration or actioned by VOICES, questioning the extent of true co-production. Figure 12 relates to peer mentoring, whereby support is given to the VOICES beneficiaries by people with lived experience who joined Expert Citizens and received training. This is used primarily for Housing First. Learning from Peer Mentoring within VOICES (which was discontinued), Expert Citizens deliver and manage Housing First Peer Mentoring. Peer mentors help to build informal relationships with Housing First customers and provide support around activities of daily life, which can be of great value to the customer. Position A stresses the positive impact of peer mentoring, while acknowledging the complexities and that such support is not a requirement of Housing First principles (i.e., a feature not common to other Housing First programmes). Position B valued the notion of peer mentoring but showed concern regarding potential negative impact on peer mentors. These included difficult situations for peer mentors who, because of pressure on themselves or from the customers, might feel obliged to act beyond the remit of their role, or feel overburdened. This poses risks to peer mentors’ mental health and jeopardises both customer’s and their own recovery process. Caution and regular monitoring have been proposed as one feasible solution.

Figure 11. Positional map for the development of Expert Citizens CIC

Figure 12. Positional map for use of Peer Mentoring

4.6 Summary of Situation Analysis: VOICES addressing failure demand through promoting equity

This section provides a summary, reflecting on the learning from sections 2 and 4, to consider VOICES efforts to address the failure demand of the support systems for local people experiencing multiple disadvantage. The last positional map (Figure 13) summarises the identified positions taken by VOICES in relation to pre-existing positions within the situation (the system of support for people experiencing multiple disadvantage) at the time of inquiry. This map also proposes a higher level explanation of how the local system’s failure demand (“demand caused by a failure to do something or do something right for the customer” [29, p26]) negatively impacted the situation as VOICES applied solutionbased responses. VOICES made considerable efforts to free local people experiencing multiple disadvantage from a system that often shifts blame to the individual for non-engagement/ non-compliance with typical processes. Figure 13 shows the differential positions of the public sector and VOICES, in relation to equality and equity. In general, equality approaches fairness as the provision of the same treatment/ support opportunities to all, whereas equity acknowledges the potentially different needs and abilities to access services provided, thus allocating treatment/ support proportionately. This seemingly small conceptual difference can have substantial implications for the support that people experiencing multiple disadvantage receive. Moreover, this provides an appropriate basis to consider differences in this system and resulting support before and during VOICES (i.e. what difference VOICES has made).

According to the evidence considered in Situational Analysis, support services more aligned with equality were mostly those of the public sector. This is perhaps not surprising as the common delivery focus is citywide and based on population needs, rather than being targeted or tailored to those with the most extreme disadvantage and needs. However, this appears to have led to the observed failure demand that exacerbates social and health inequalities between the local general population and those experiencing multiple disadvantage. A series of examples have been presented in VOICES reports that show how people experiencing multiple disadvantage have been excluded from services for which they were eligible, and entitled to. Some of these are illustrated in Position A of Figure 13. Legal literacy and misinterpretation of the legislation’s inclination toward equity affects many services, excluding the VOICES customer group from social, health and financial services. In turn, the observed lack of responsibilitytaking in the public sector for those experiencing multiple disadvantage, alongside reactive and untargeted nature of some provision (e.g., prison release plans, hospital discharge), were illustrations of the causes of the revolving door issue, whereby those with the greatest needs are continually in/out of the same local support services (often in crisis). Finally, Position A also notes the perpetuation of the traditional treatment first or temporary hostel accommodation policy that had failed to address local chronic homelessness.

Figure 13. Equality vs. equity and the system's failure demand

It is also clear that ‘equality’ was the common target within the diverse local system’s support services. In systems thinking, this could be explained by ‘system’s perpetuation’. Specifically, this mean that various sub-systems in this situation (e.g., prison release, hospital discharge) aim to treat everyone equally (i.e., towards a target of equality), which is reflected in the whole system’s behavior. However, for those experiencing multiple disadvantage who need additional, specific support, the result is exclusion and marginalisation. Furthermore, the equality principle and policies favour those in better social, health and mental position, rather than people experiencing multiple disadvantage resulting in the ‘competitive exclusion principle’; a ‘gravitational force’ that keeps people experiencing multiple disadvantage in the same vulnerable position [30]. Eventually, when the problematic situation becomes unmanageable and overburdens the system (in what is called a ‘feedback delay’), the need to turn to more systems thinking solutions is acknowledged; in this case, such solutions were attempted through Fulfilling Lives and VOICES. VOICES acknowledged the need to focus on equity as the target. The aim was to approach this through implementing changes on every level at the situation, as illustrated in Position B (fig 13). Initially, the emergence of Expert Citizens as ambassadors for people experiencing multiple disadvantage redirects the focus of the local support system. According to system thinking, changing one element cannot be expected to drastically transform the system as a whole. However, it could cause a redirection of priorities if the change is accompanied by analogous changes in nested systemic relationships. For example, it was achieved in this case through supporting Expert Citizens not only to become an independent CIC, but by acknowledging the need for skilful personnel who are accredited and trained to particate equally as co-designers (i.e., Care Act toolkit), coresearchers (i.e., interviewing and collecting data at various VOICES reports) and co-evaluators (i.e., INSIGHT), with VOICES and partner organisations. This is expected to provide gradual and long-lasting change that will steadily help to transform the face of the local support system. VOICES acknowledged the need for great systemic changes. That was mainly achieved by:

a)

b)

c) Transforming VOICES to a totally co-produced project (of constantly adapted, innovative, diverse but autonomous partnership. Adopting an “evolutionary learning” approach, which acknowledged the complexity of the support system for people experiencing multiple disadvantage (i.e., the situation); e.g., the Learning Programme for workforce development around working with this population; WBLL to improve legal literacy; commissioning research and evaluation around VOICES activities to inform practice. Overcoming professionals’ assumptions of who knows best, acknowledging the importance of lived experience as basic component of their own learning process and being open to constructive criticism as opportunities to learn and adapt