PIERRE BONNARD

p. 51

MAURICE

DENIS

p. 79

CHARLES

FILIGER

p. 105

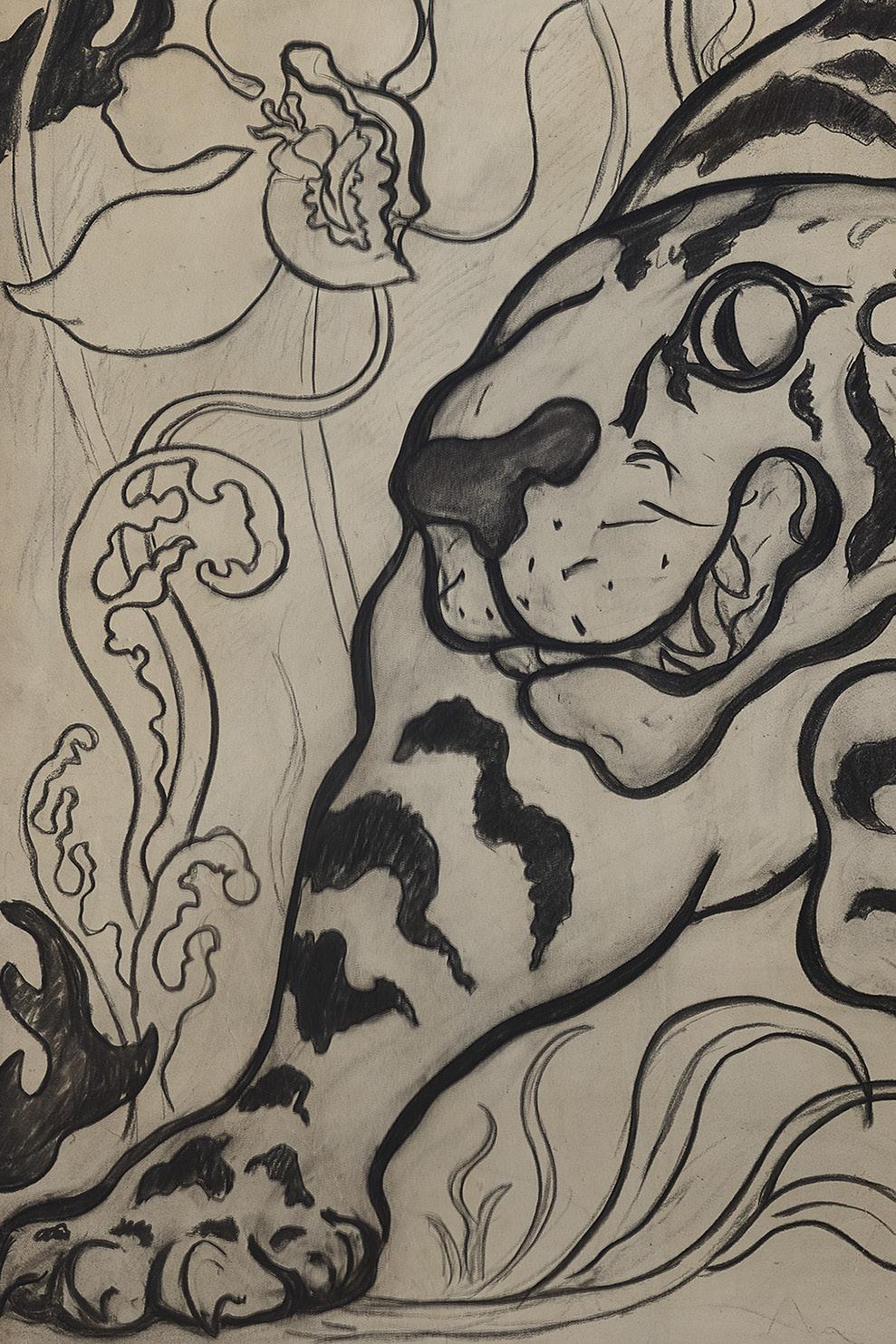

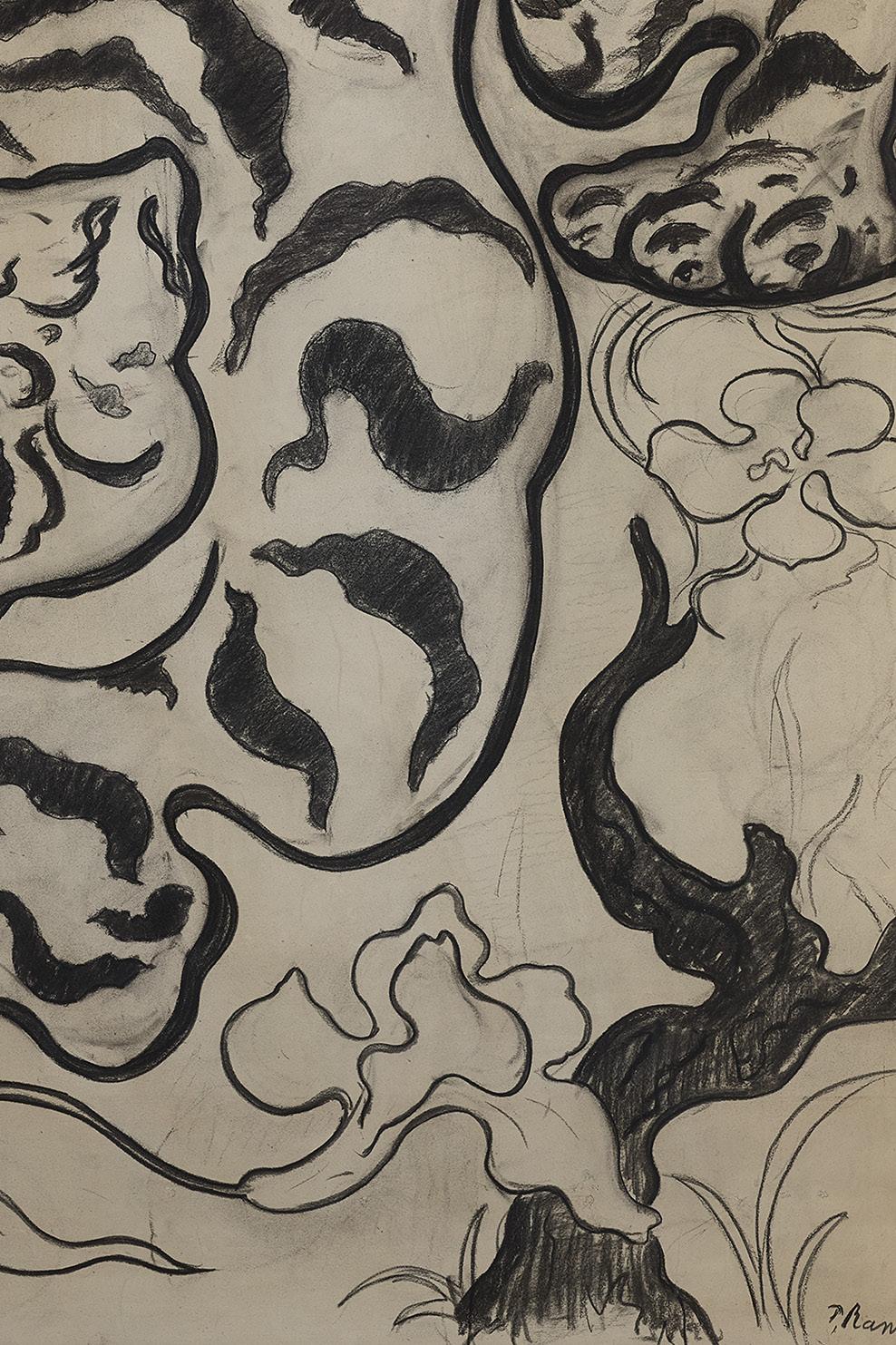

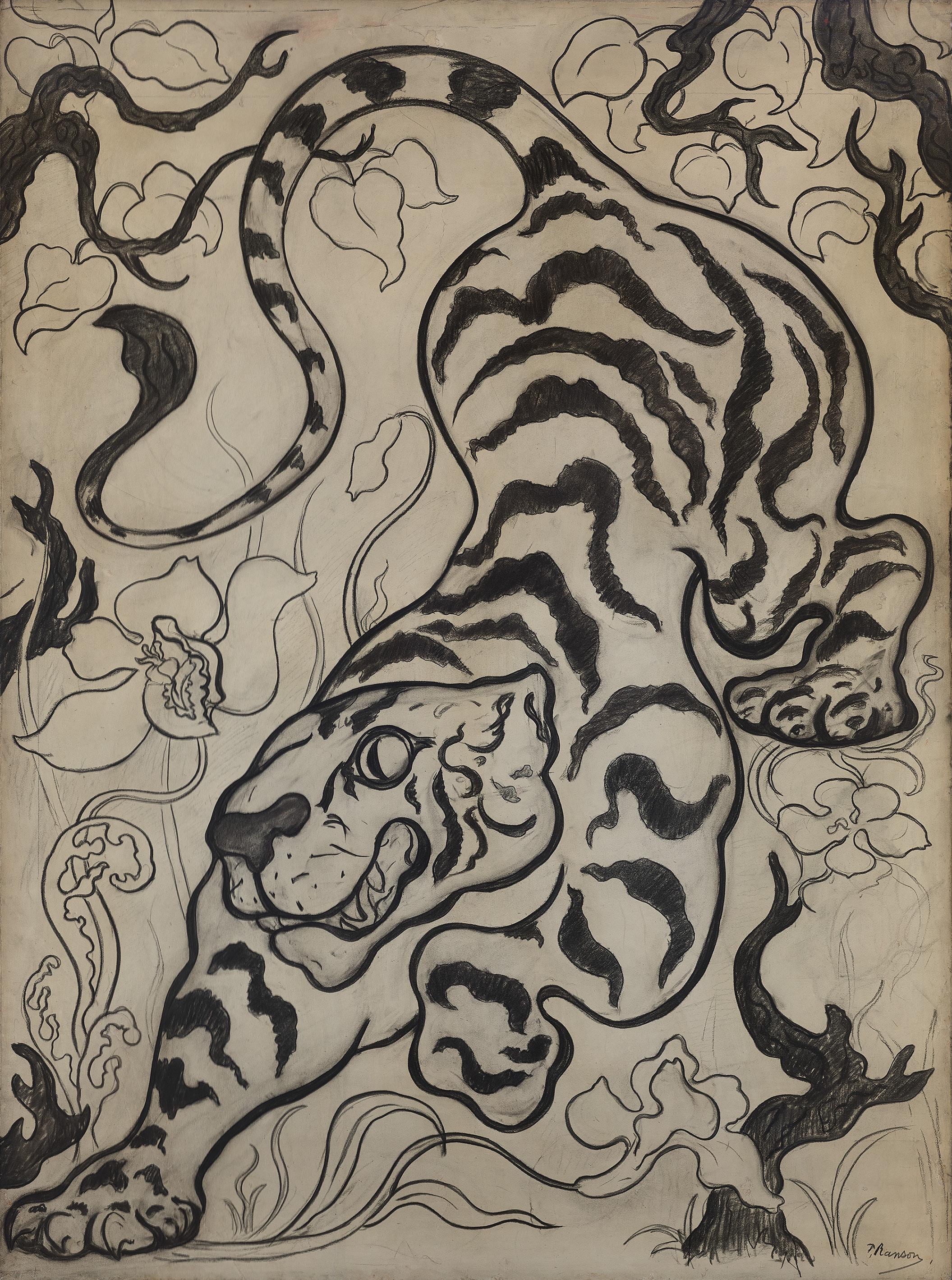

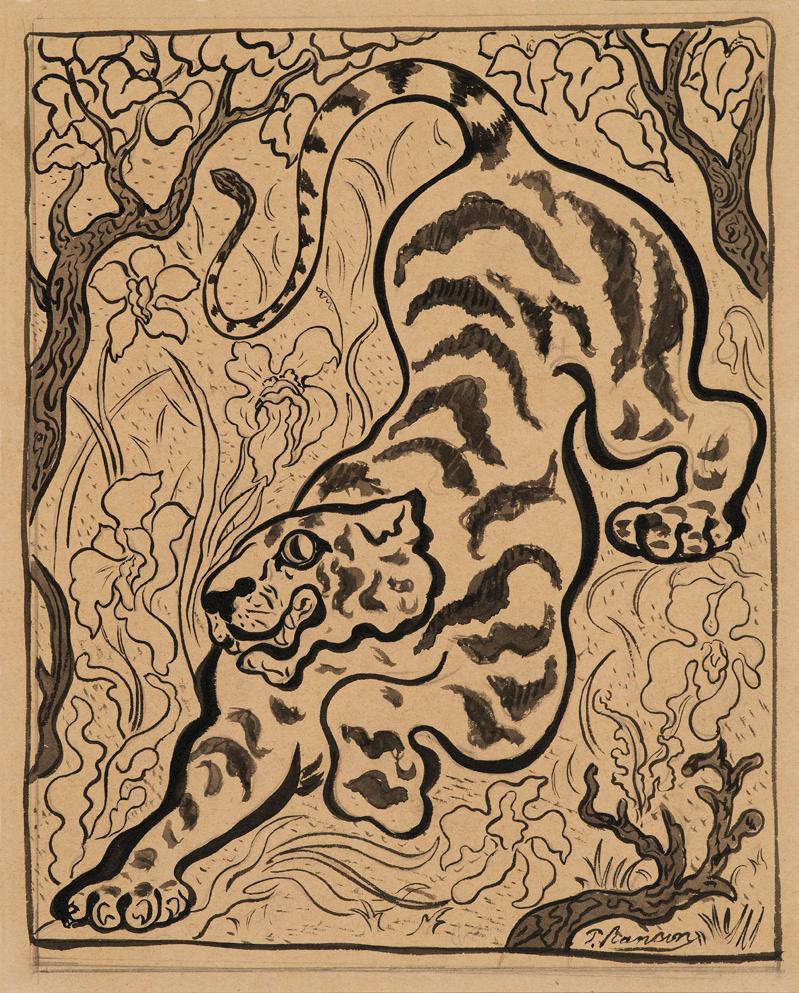

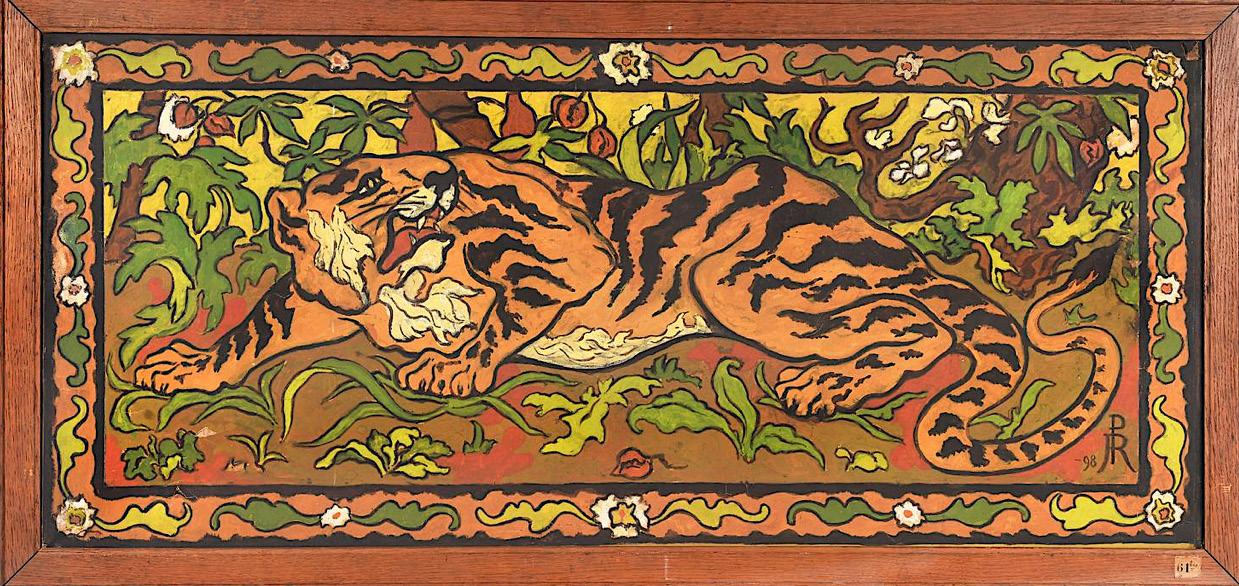

PAUL RANSON

p. 129

JÓZSEF

RIPPL-RÓNAI

p.145

KER-XAVIER

ROUSSEL

p. 155

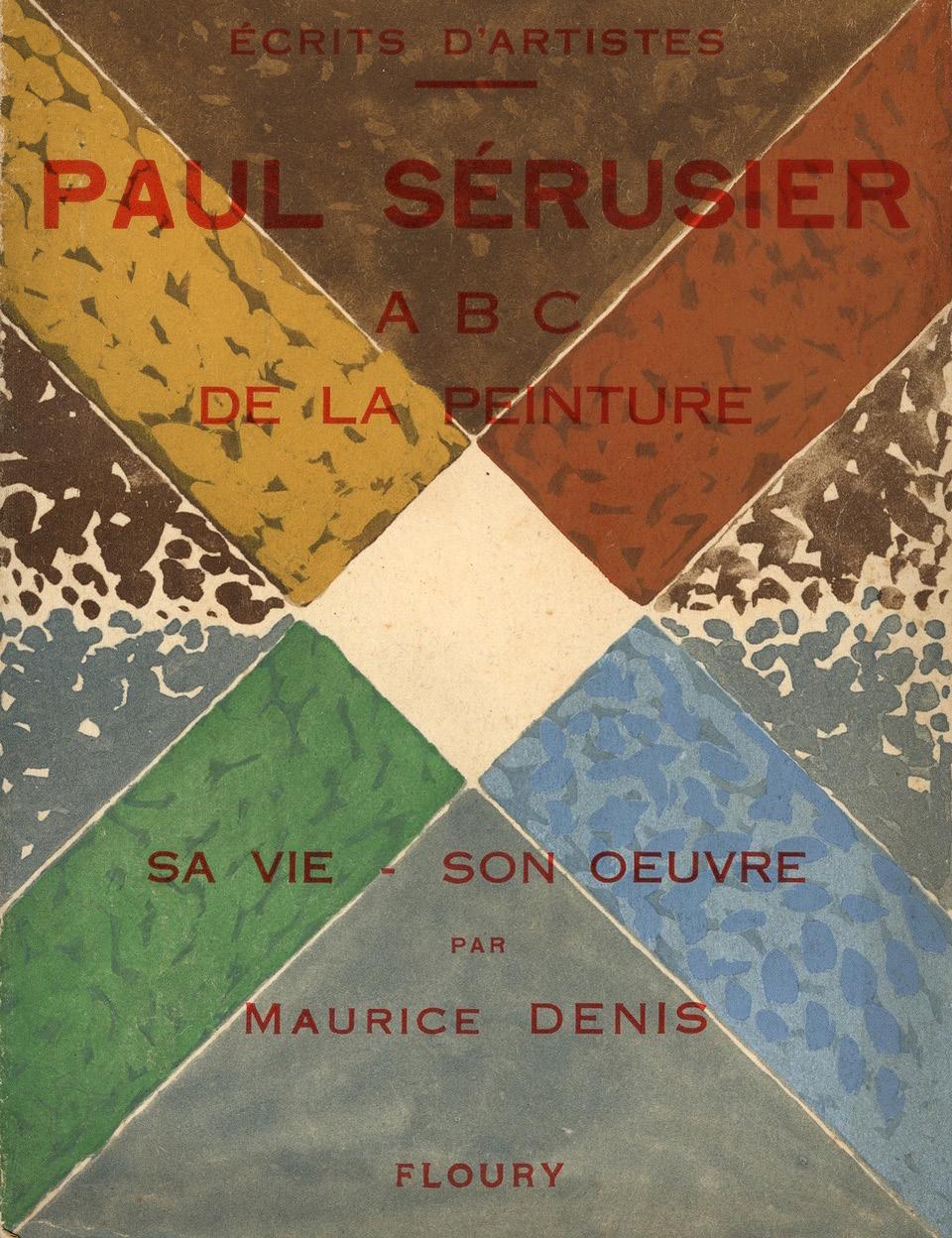

PAUL

SÉRUSIER

p.165

FÉLIX

VALLOTTON

p. 181

ÉDOUARD VUILLARD

PIERRE BONNARD

p. 51

DENIS

p. 79

CHARLES

FILIGER

p. 105

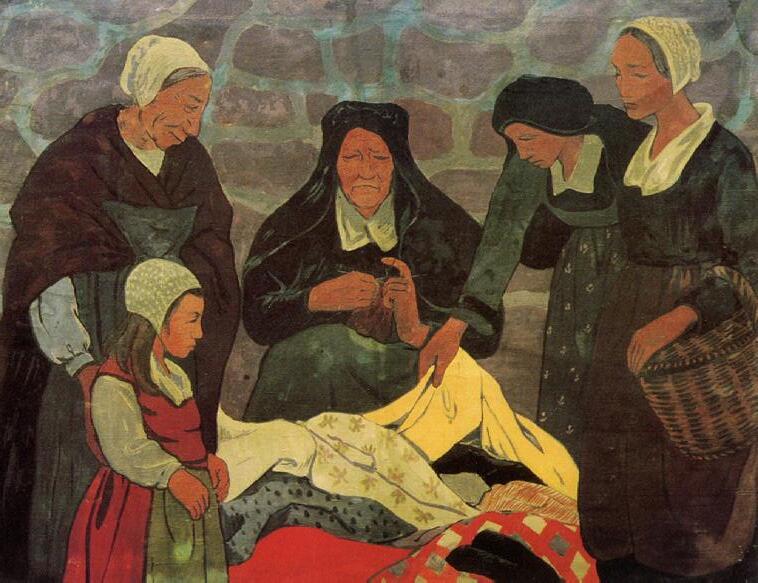

PAUL RANSON

p. 129

JÓZSEF

RIPPL-RÓNAI

p.145

KER-XAVIER

ROUSSEL

p. 155

PAUL

SÉRUSIER

p.165

FÉLIX

VALLOTTON

p. 181

ÉDOUARD VUILLARD

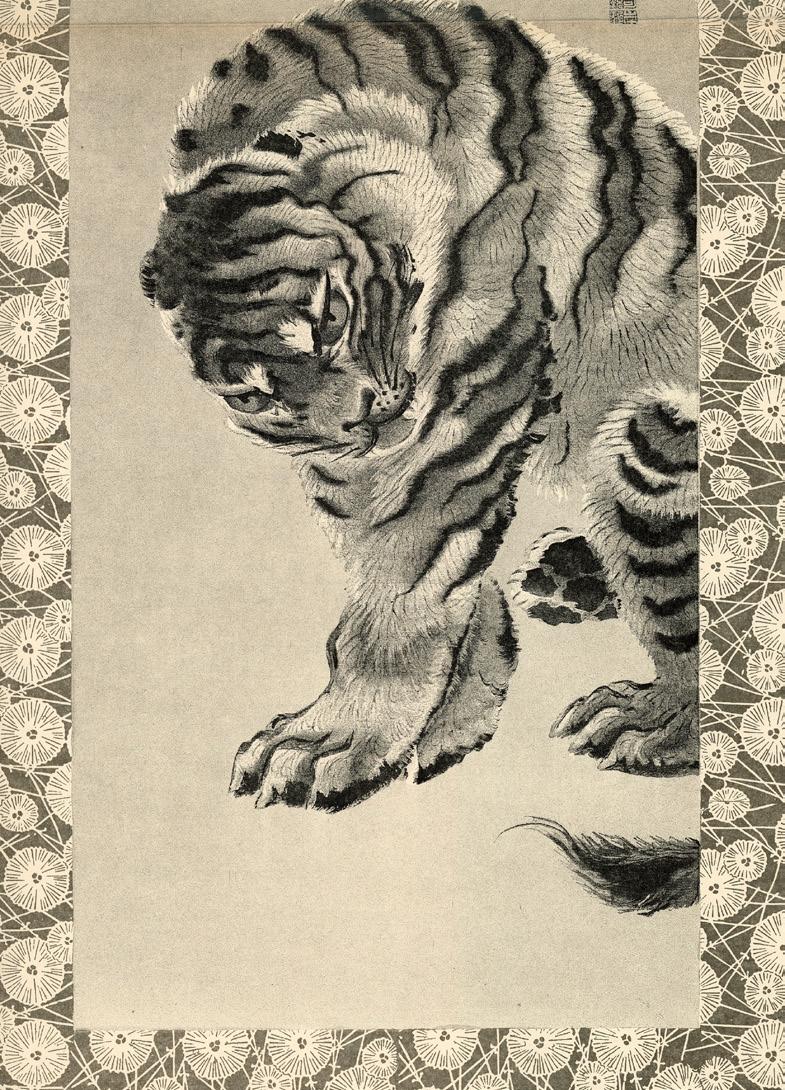

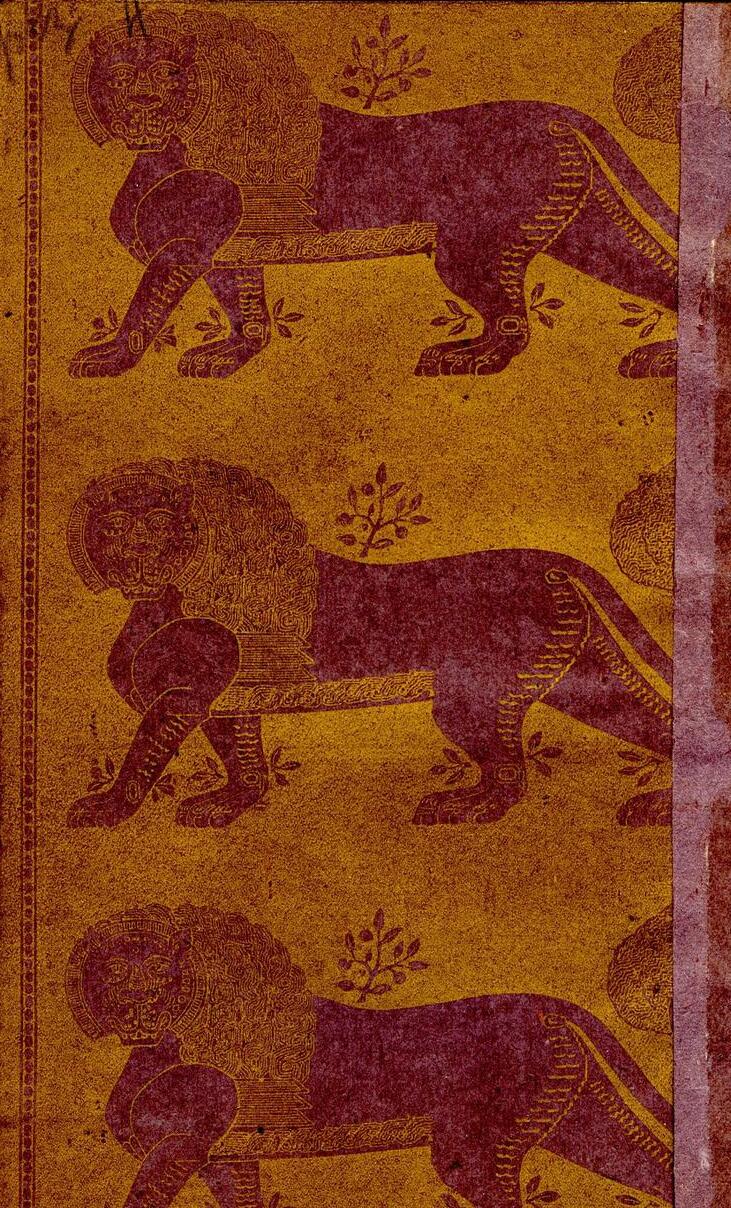

The story of the Nabis began with the close friendship between a group of teenage artists, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis, at the Lycée Condorcet in Paris in the period 1885–87. To understand the birth of their artistic calling, one has to picture their passionate discussions about the writers (Baudelaire, Verlaine and Mallarmé) and the philosophers (Schopenhauer and Bergson) introduced by their teachers; to imagine their first artistic emotions at the Louvre and at the revelation of Paul Gauguin’s painting; to share their astonishment at the Japanese prints exhibited at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890; and to understand the flux of new artists, both French and foreign, who shared their ideals and gradually joined their group – Paul Ranson, Georges Lacombe, Félix Vallotton, József Rippl-Rónai and others. And thus the group of ‘Nabis’ (the Hebrew word for ‘Prophets’) was born.

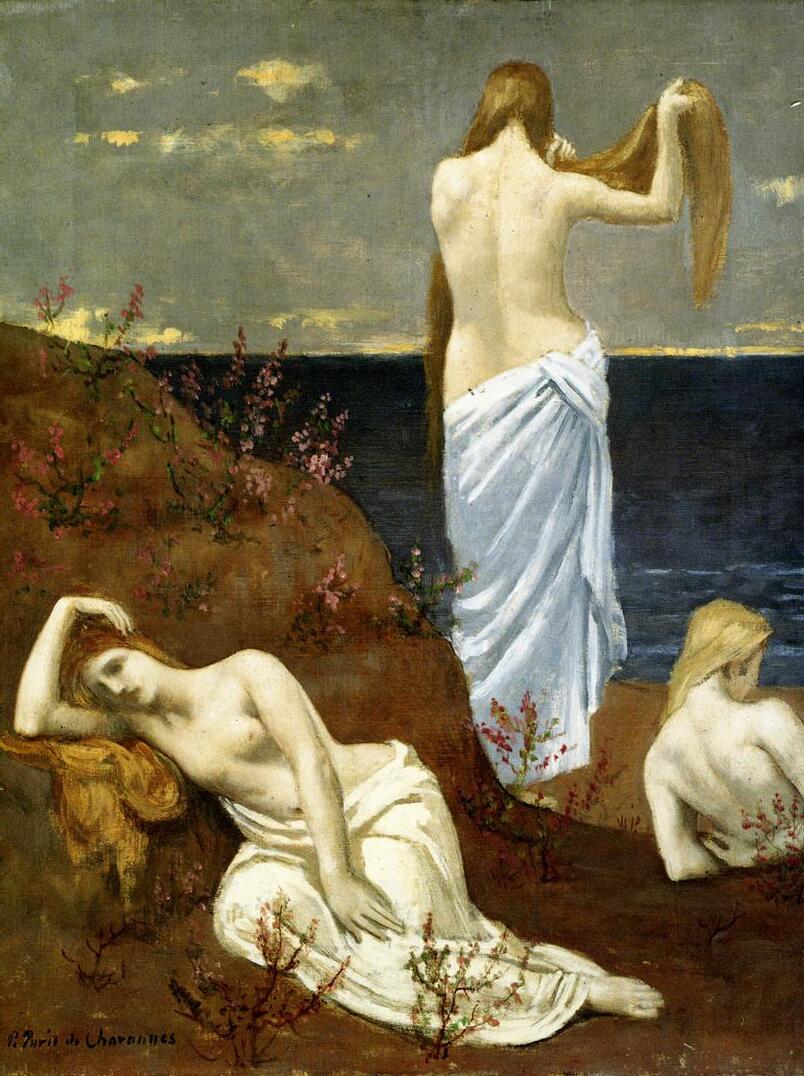

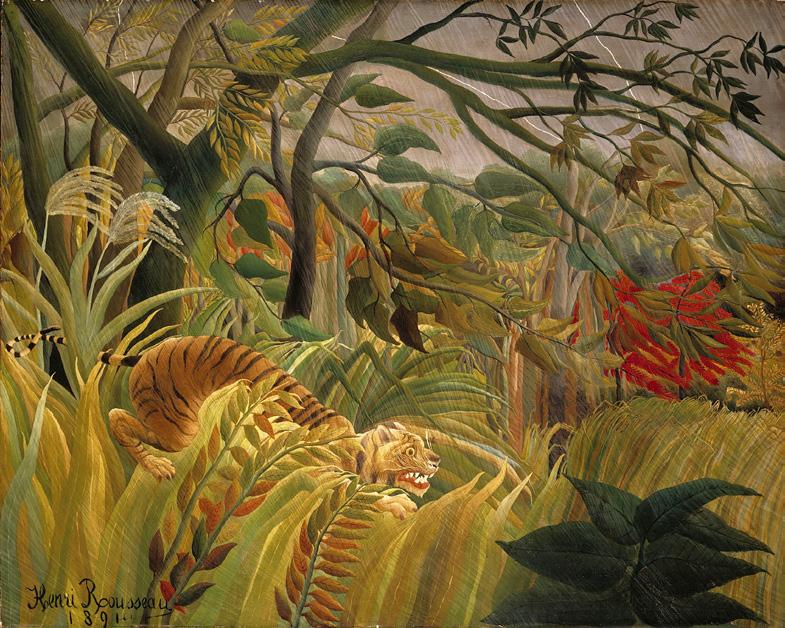

The group called themselves ‘Nabis’, recalling the English Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, to reflect the quasi-spiritual dimension of their shared admiration for Gauguin. It was not by chance that they titled the painting made in summer 1888 by Paul Sérusier under Gauguin’s direction – which became the medium for transmission of this aesthetic – ‘The Talisman’ (Paris, Musée d’Orsay). However, the true breakthrough for the Pont-Aven School’s painting came at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, when works by Gauguin and his circle were displayed on the walls of the Café Volpini. It was there that the Nabis saw a style of painting that went beyond Impressionism. With his unrestrained brushstrokes and flat tints, Émile Bernard produced almost abstract paintings, such as L’Orchestre (c. 1887) [p. 14], creating an aesthetic from the PontAven School that inspired Paul Sérusier to use the same flat tints in his Bretonne

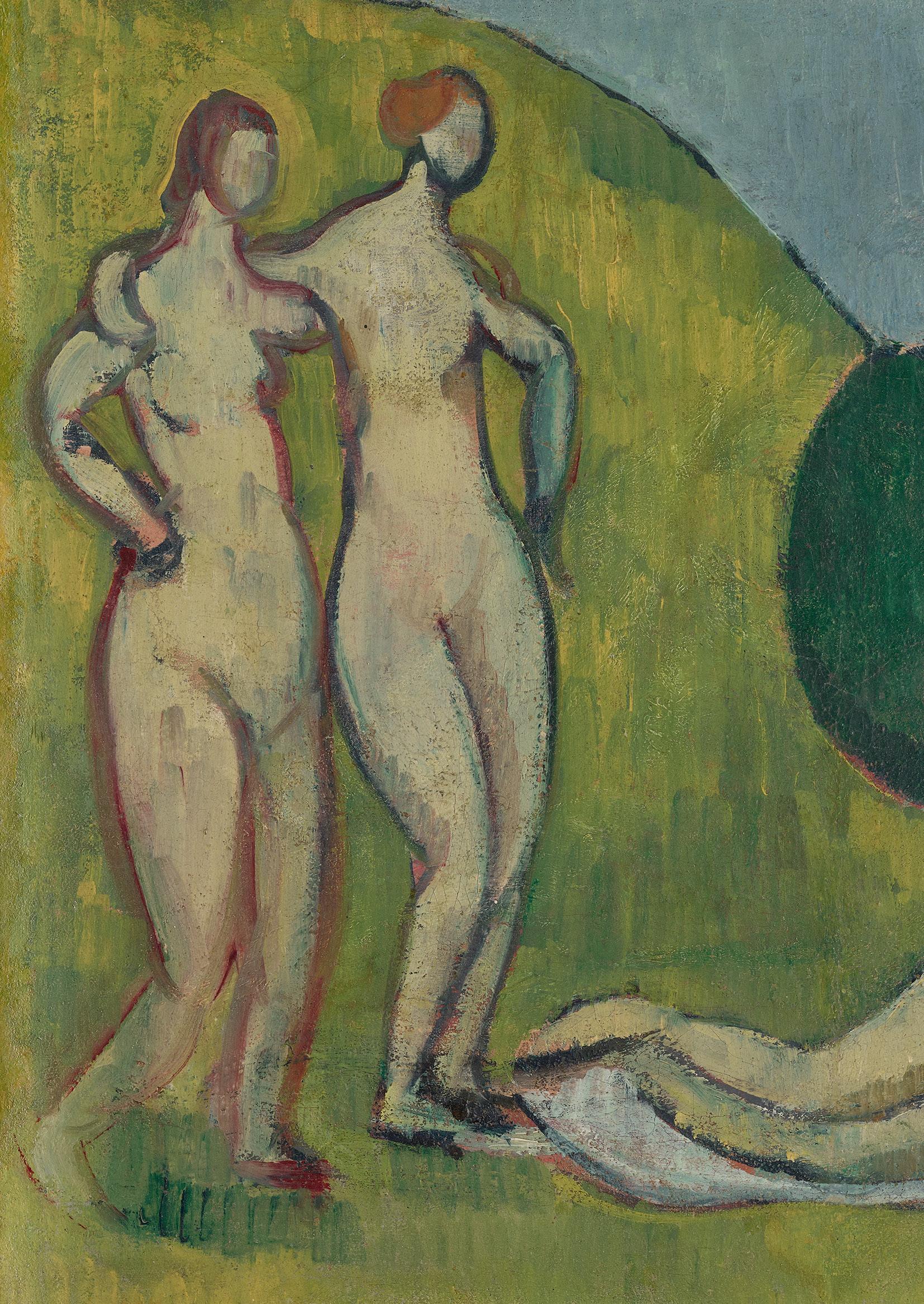

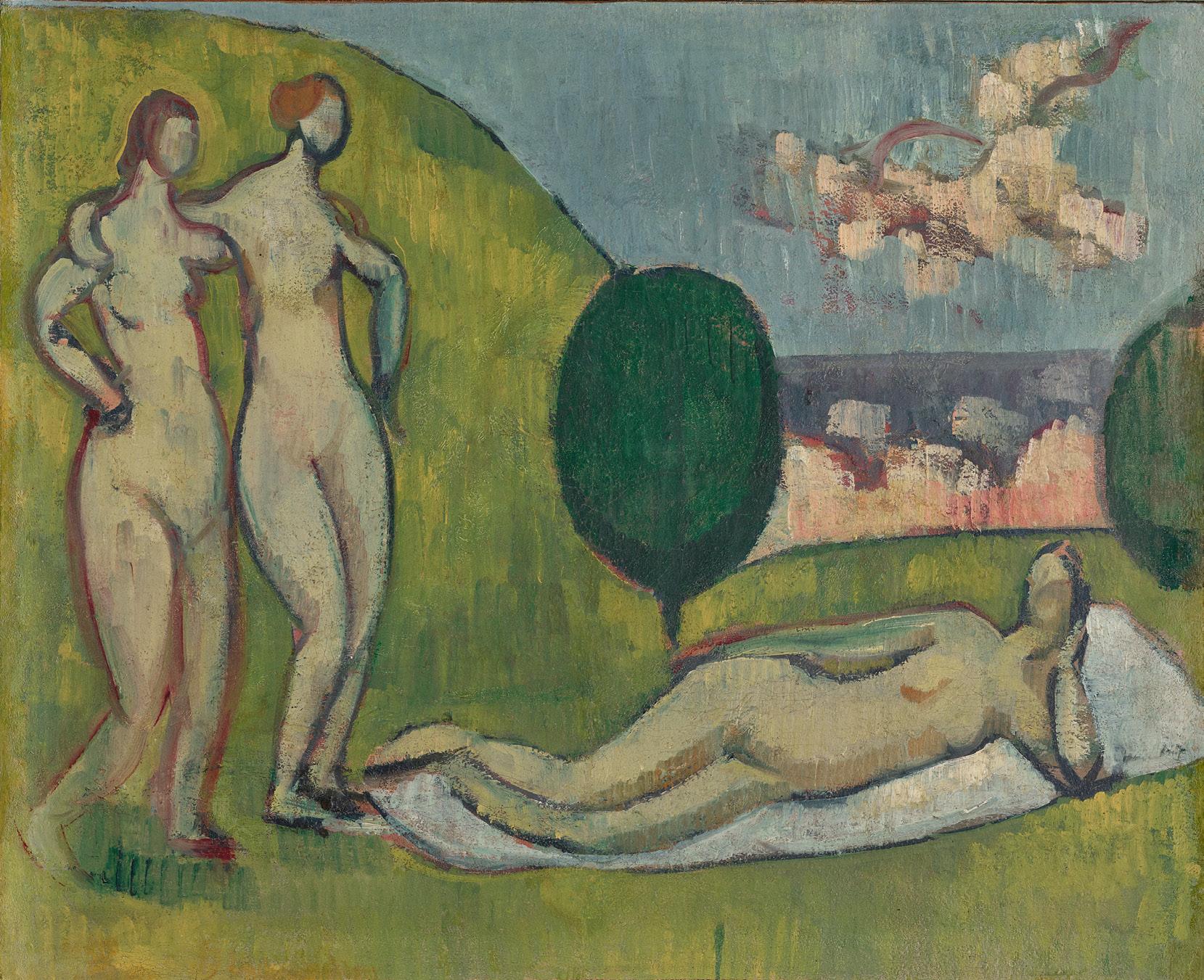

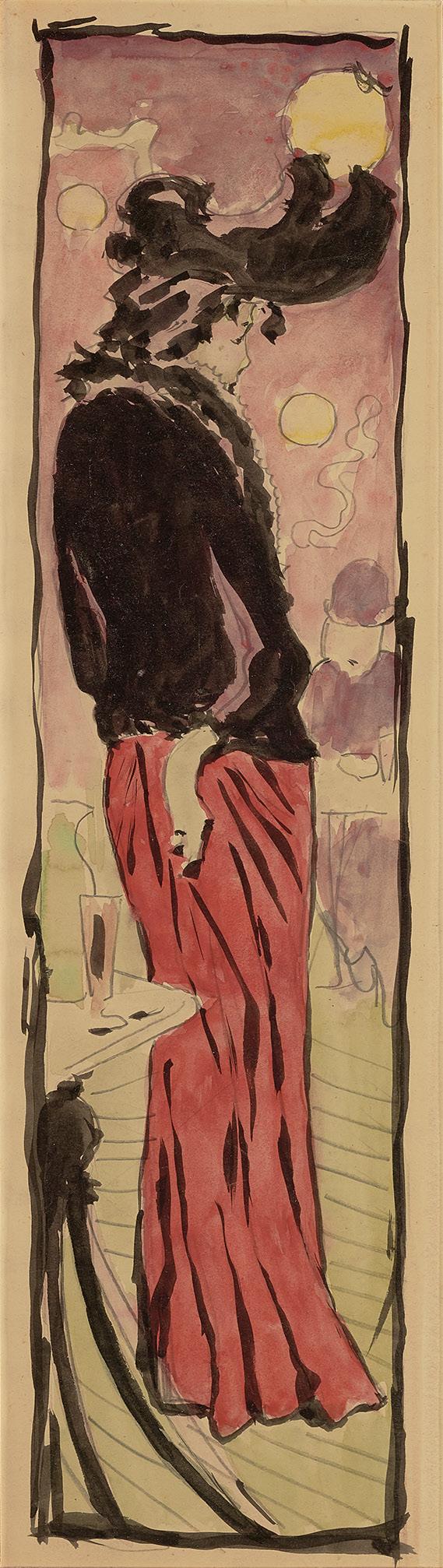

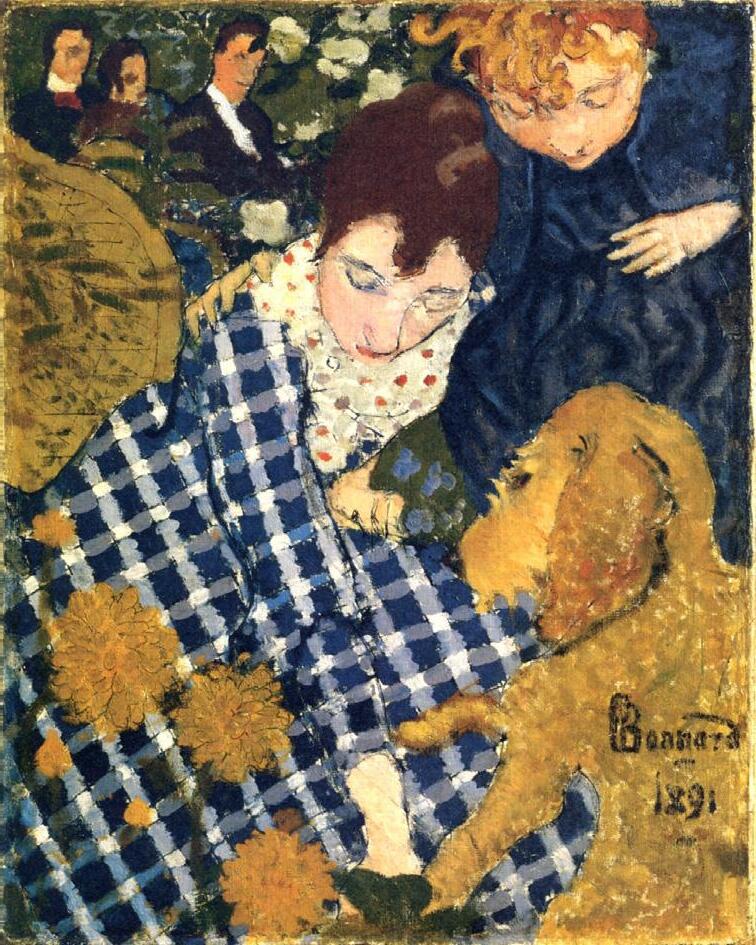

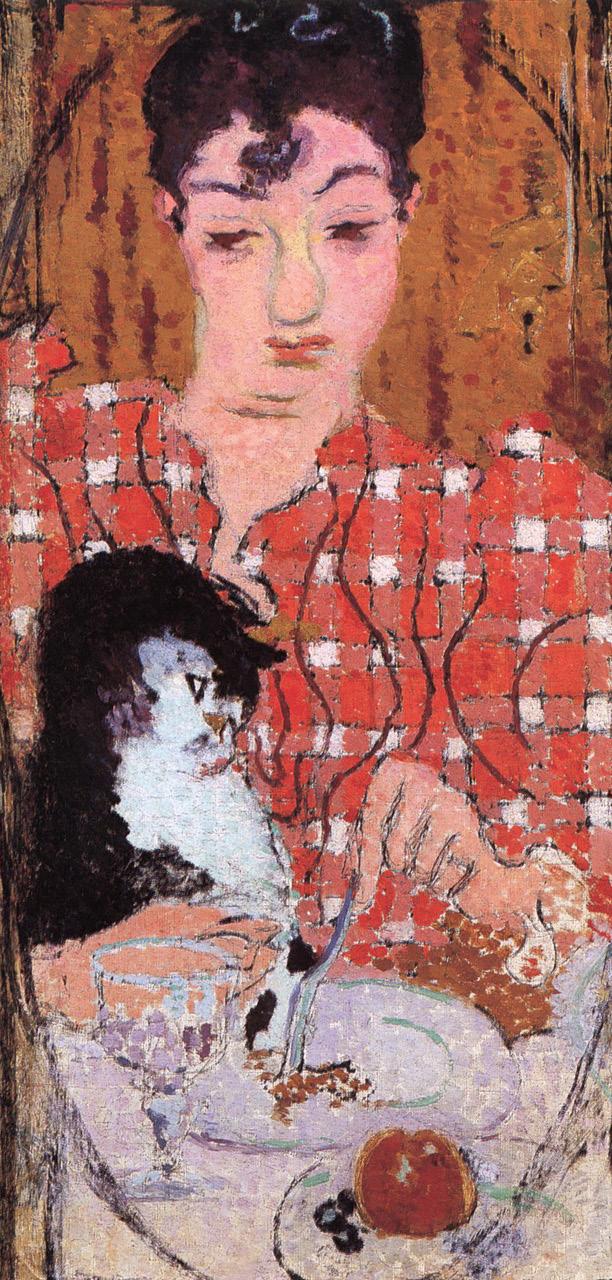

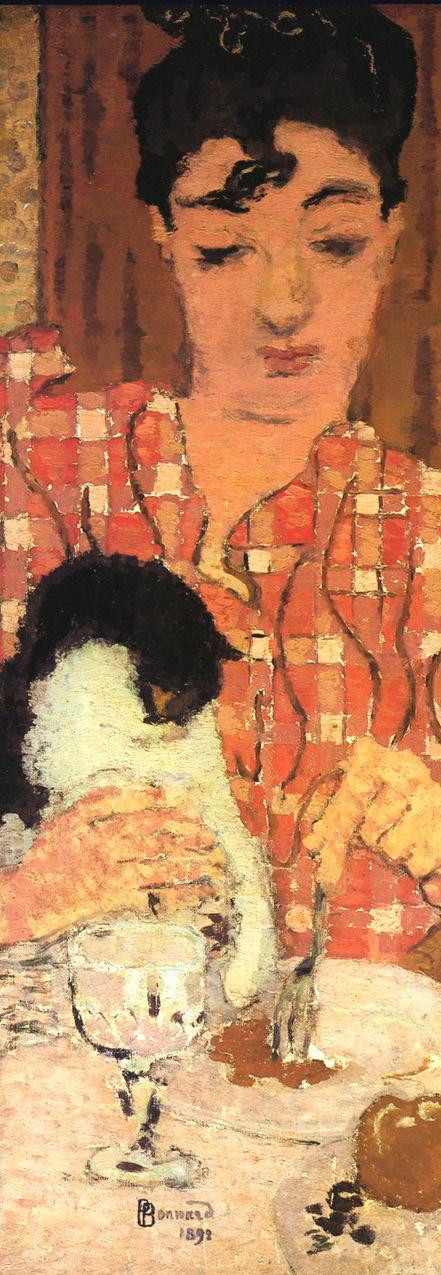

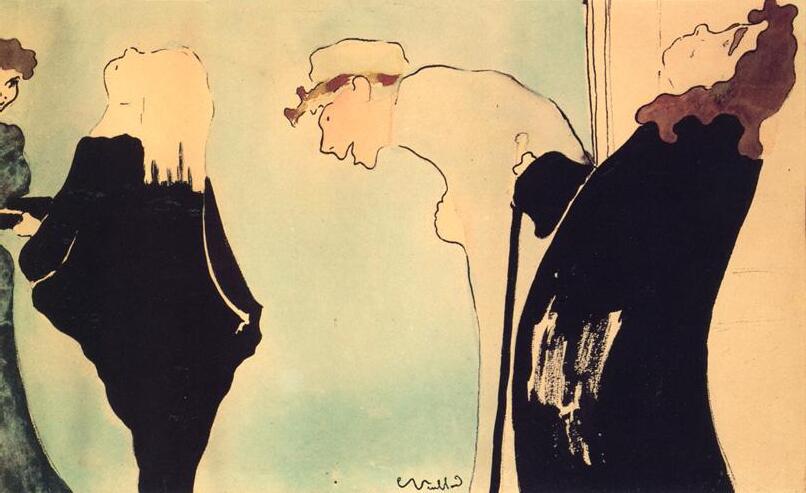

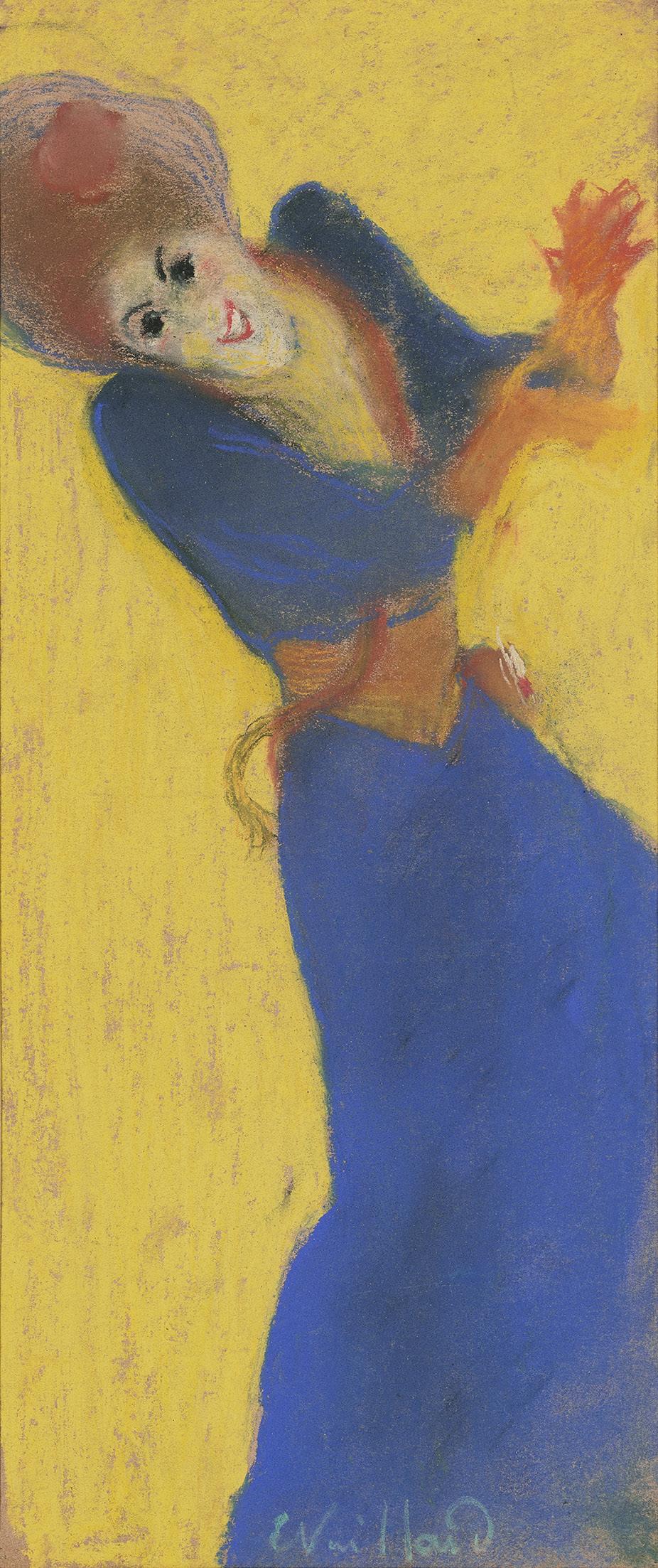

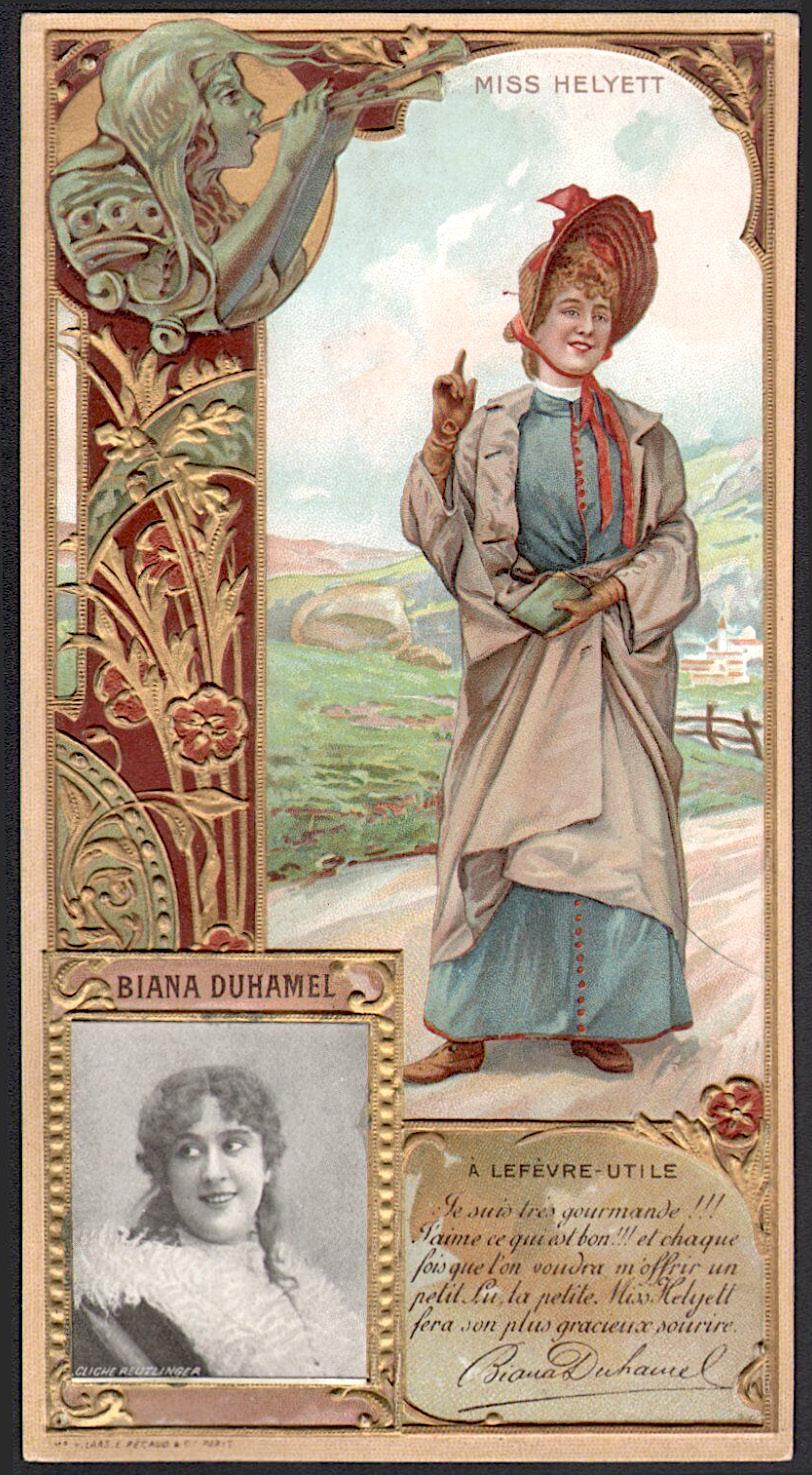

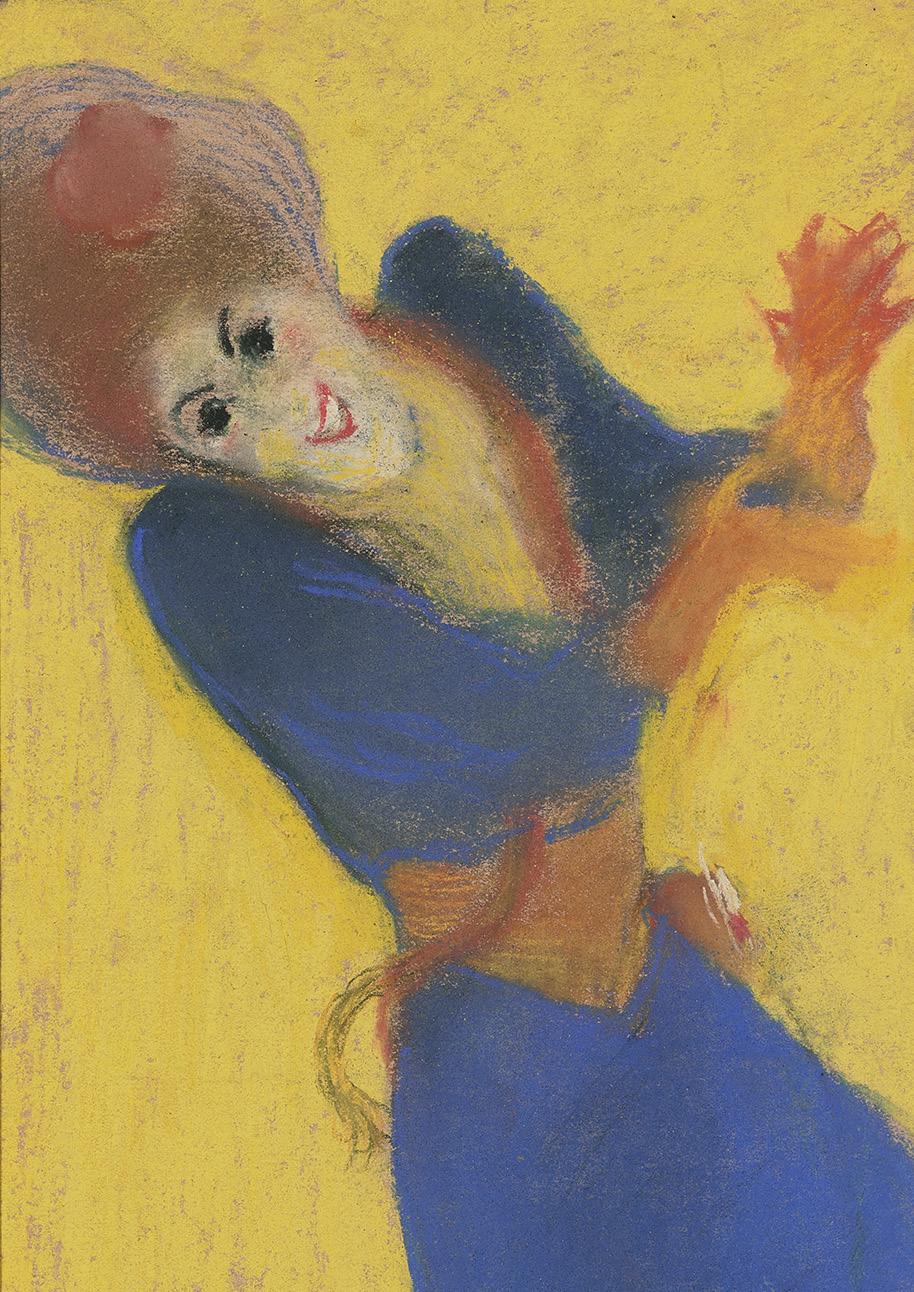

allaitant (1892) [p.158], a masterpiece of these radical years, and Denis in Devant la fenêtre bleue (1894–96) [p. 74]. In Nus dans un paysage (c. 1887) [p. 10], Bernard combined the simplification of volumes that had been so important to Paul Cézanne with the visual solutions invented by Gauguin. The elongation of the figures’ bodies, especially of the reclining bather, is evocative of the earlier imaginings of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). The Nabis were also interested in the Neo-Impressionism of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Long underestimated by art historians, this influence is essential to understanding the development of the group’s aesthetic: it is apparent in Bonnard’s study for Le Corsage à carreaux (1892) [p. 34], and Denis’ Marthe au tablier rouge (c. 1892) [p. 58]. The Nabis were also passionate about Japonisme, as is evinced by Bonnard’s Au café (c. 1890) [p. 20] and Vuillard’s Biana Duhamel dans le rôle de Miss Helyett (1891) [p. 202]. The kakemono format used by both seems to have been directly inspired by the prints published by Siegfried Bing in his review Japon Artistique (1888–91), some of which, furnished in several folds, could be removed from the review and hung on the wall.

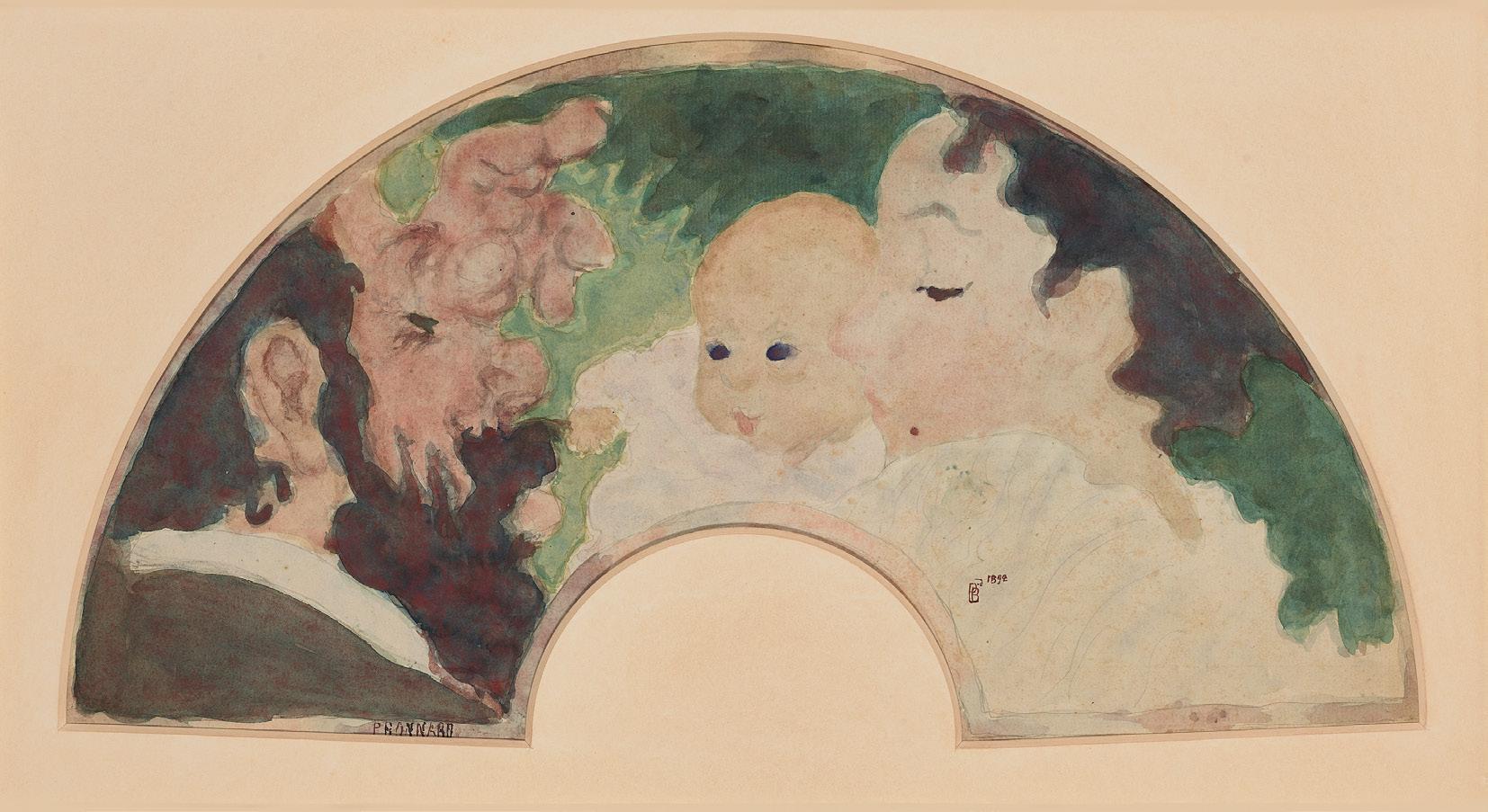

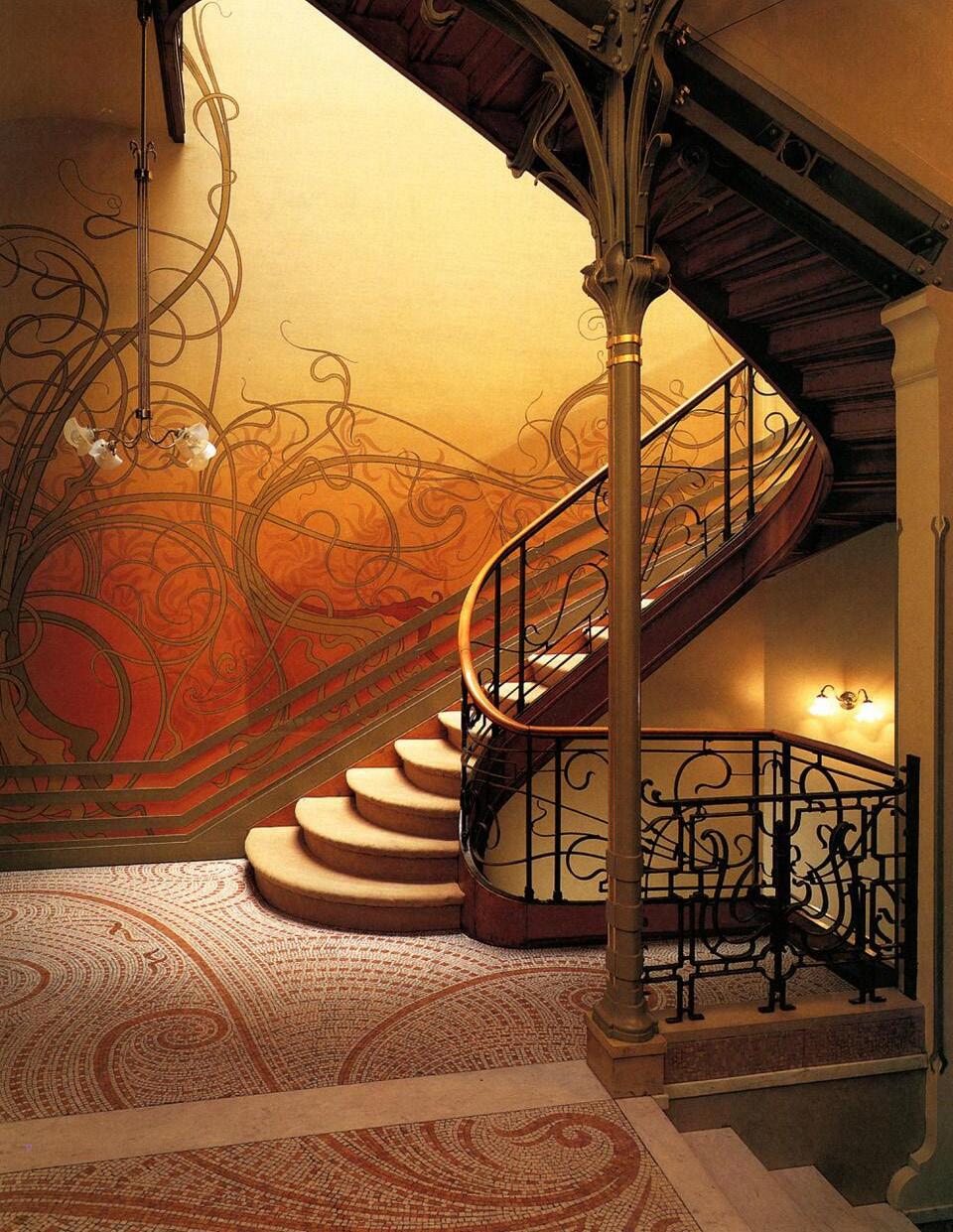

In their combat against the hidebound nature of the official academies, the Nabis aimed to do away with boundaries: those that separated the ‘major’ from the ‘minor’ arts, those between subjects considered worthy of the Salons with others reduced to purely private consumption, and the boundary between easel painting and the decorative arts. Furthermore, like the Art Nouveau designers, whose contemporaries and sometimes friends they were, the Nabis’ goal was to create ‘Total Art’ decors. In addition to their easel paintings, they conceived a great many objects of daily life, for example, Denis’ design for a lampshade, Au Pont du Nord un bal était donné (1894) [p. 65], in which he transformed a folk song into elegant Japanizing

arabesques; and Bonnard’s design for a fan, La Famille Terrasse (c. 1892) [p. 43], in which the figures and setting were taken from his lithograph Scène de famille of 1892. It is clear today the degree to which the Nabis heralded the twentieth-century revival of the decorative arts (textiles, the arts of fire – glass and ceramic, and so on): Henri Matisse was their direct heir.

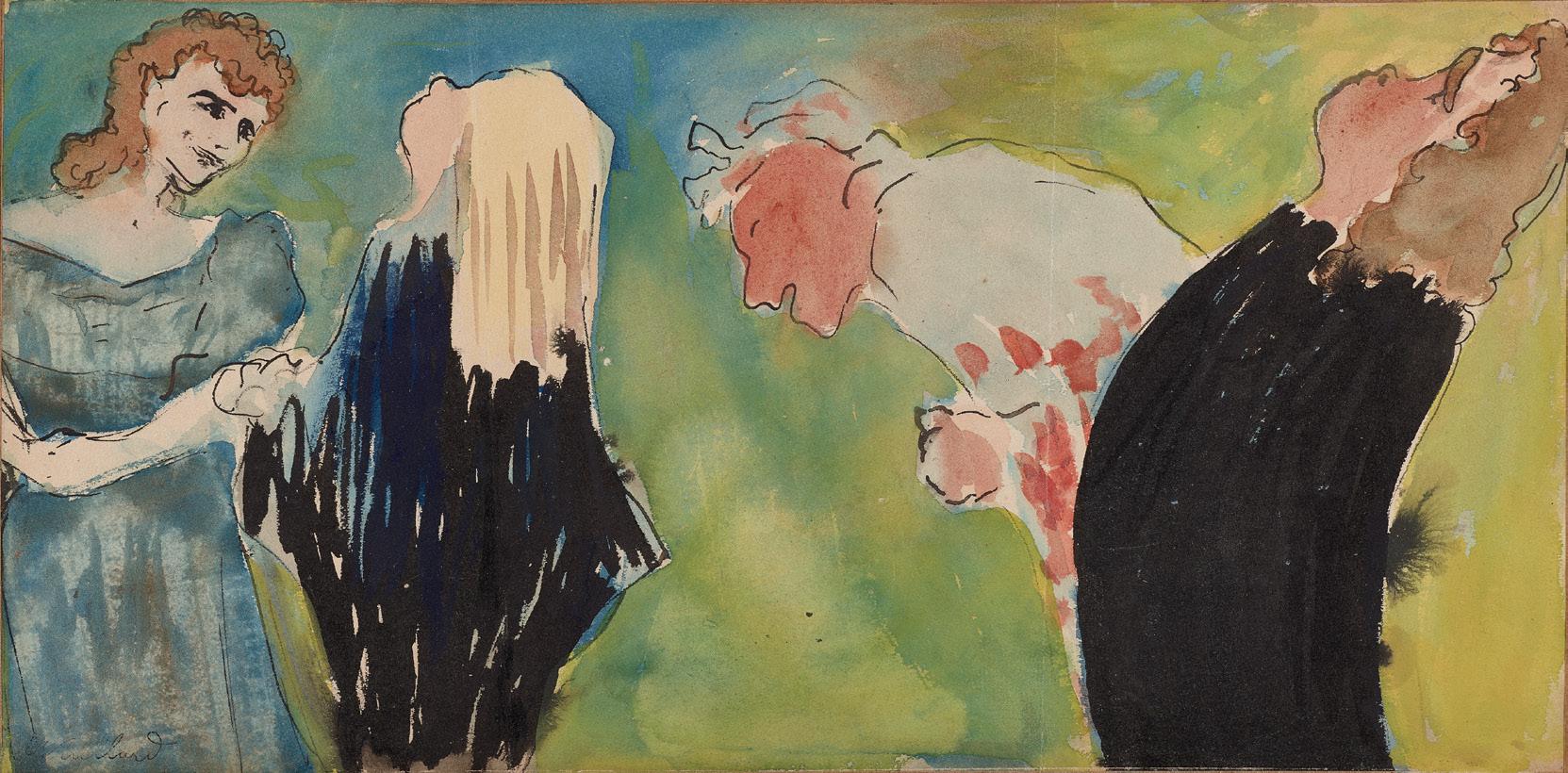

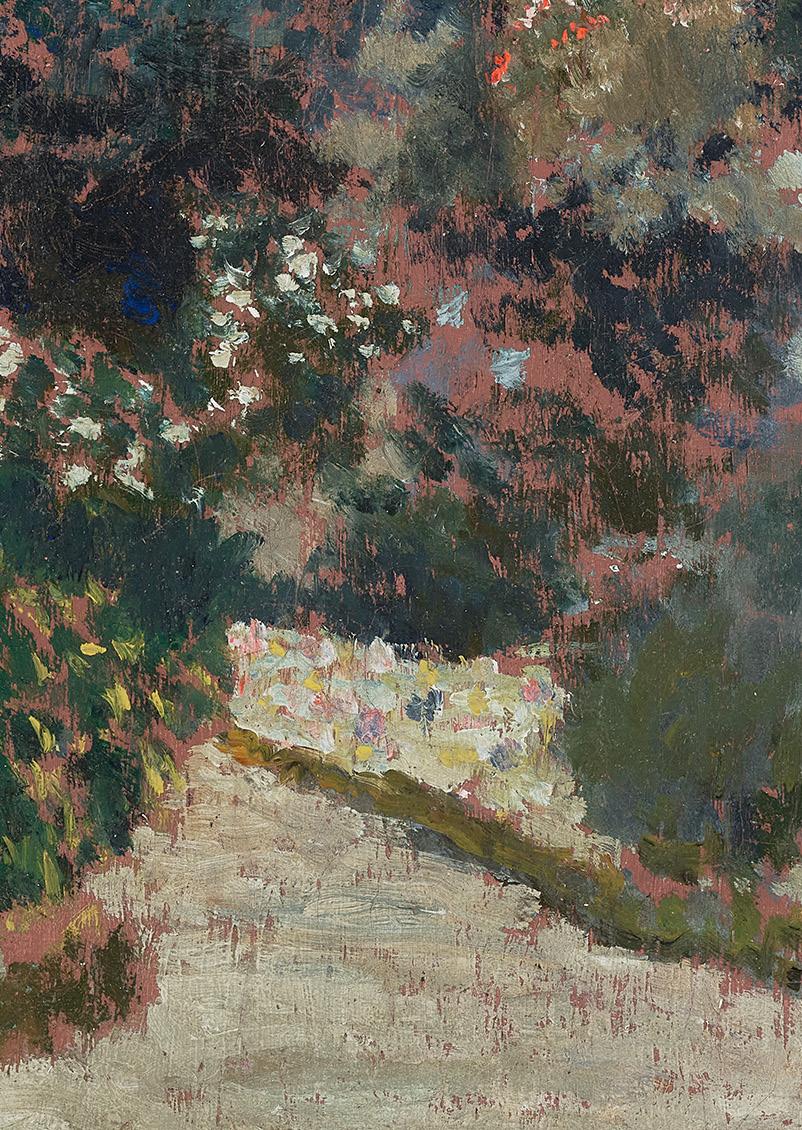

Art and the formation of its history are never dissociated from the societies in which they develop. For this reason, recent exhibitions on the Nabis have explored the relationship between this group of exclusively male painters and women. In the tireless observation of their domestic environments, the Nabis used their mothers, partners, wives and sisters as their primary models. This was the subject of the very recent exhibition ‘Private Lives, Home and Family in the Art of the Nabis, Paris, 1889–1900’ (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH , 2021). Vuillard’s mother was a fundamental reference point in his emotional landscape, as was recently made clear in the exhibition ‘Maman: Vuillard and Madame Vuillard’ (Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, UK, 2018–19). The title, inspired by Vuillard’s own terms of affection, should not mask the richness (and complexity) contained in these moments of everyday life captured by the painter. Consider also the sometimes almost theatrical portrayals he gives of his sister, Marie, the future wife of his friend the painter Ker-Xavier Roussel, for example in the strange and original Marie au jardin (1893) [p. 210] – shown to one side of an expanse of profuse vegetation, she appears to have the same texture as the greenery. Vuillard’s point here is that we are all literally inhabited by the places and objects by which we are surrounded. A follower of young philosophers like Bergson, Vuillard expressed concepts since developed by contemporary psychology. Visitors to the recent exhibition ‘Femmes chez les Nabis, de fil en aiguille’ (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Pont-Aven, FR , 2024) discovered that some of these women had been artists and had contributed to the discourse and philosophy of the Nabis. One was

Marthe Meurier, seen in Marthe au tablier rouge (equisse) (c. 1892) [p. 58], who collaborated on the paintings of her beloved Denis by adding poetic painted flowers to the compositions.

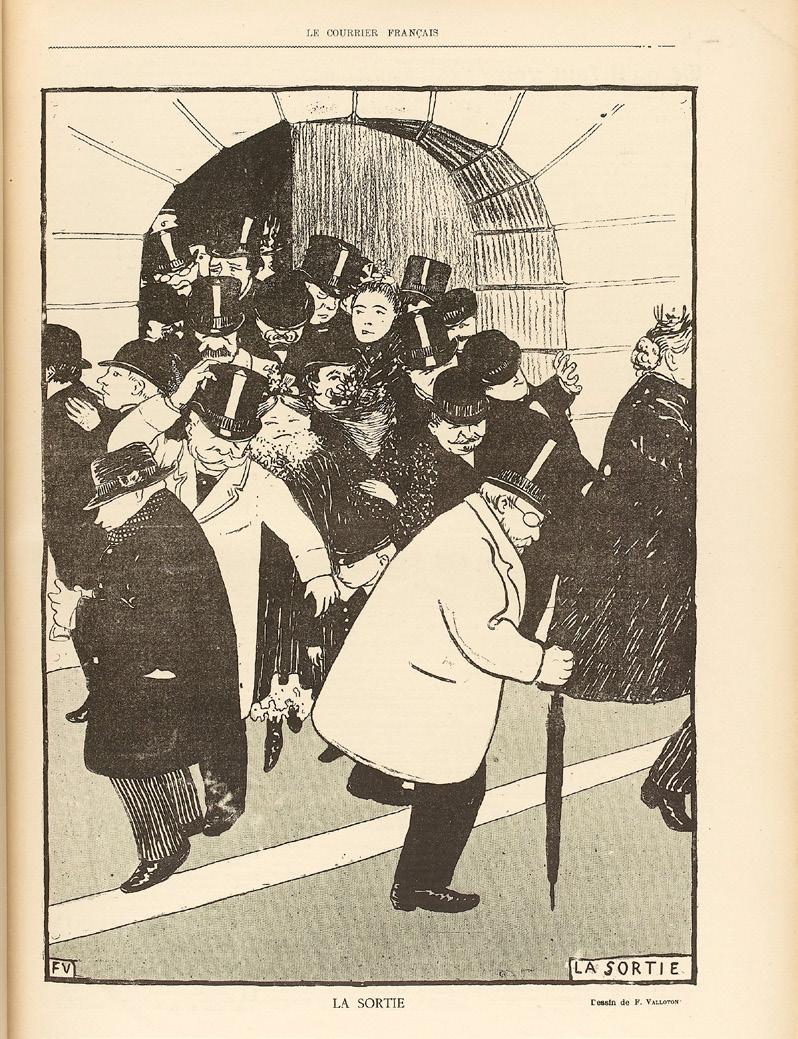

For a long time, the dealings of the Nabis group were limited to a tight circle of initiates. At first, they were supported by Symbolist writers (Mallarmé, Kahn and Mirbeau) and their works collected by their immediate entourage; for example, by the actor Coquelin Cadet (1848–1909), who was involved in the avant-garde theatre that so fascinated the Nabis. Vuillard painted the actor’s portrait in a radical manner on many occasions, as in Coquelin Cadet dans “Le Malade imaginaire” (c. 1890) [p. 184]. Another was the brilliant art critic Gabriel-Albert Aurier, who was one of the first to understand Vincent van Gogh’s painting and who wrote a pioneering article in 1892: ‘Les Symbolistes’ in La Revue Encyclopédique. Aurier owned Bernard’s L’Orchestre and Nus dans un paysage, as well as Bonnard’s Au café and Villa Bach (La Chasse à courre) (1890–91) [p. 28]. Subsequently, the Nabis experienced a period of disenchantment from ‘modernist’ critics who only had eyes for Cubism, which probably culminated in 1947 with the article published in Les Cahiers d’aujourd’hui in which Christian Zervos asked whether Bonnard was a ‘great painter’. Matisse took it upon himself to give a categorical reply! During the 1960s, enterprising American collectors showed a passion for the Pont-Aven School and the Nabis: Arthur Altschul, whose collection represented a landmark in art history, acquired Charles Filiger’s Sainte Famille (1891) [p. 88] and Paysage de Bretagne (1892–93) [p. 94], and Félix Vallotton’s La Sortie (1894) [p. 176], while Robert Walker, based in Paris, owned Filiger’s Lamentations sur le Christ mort (c. 1895) [p. 100]. Sam Josefowitz’s fascination with the Nabis was fundamental to the movement’s recognition. Owning some of the greatest masterpieces by Vuillard and his friends, he was the instigator of a number of important travelling exhibitions. Official

recognition of the Nabis followed with major international retrospectives. In 1984, the Bonnard retrospective (Paris, Washington and Dallas) was the first to highlight the links between Bonnard’s late period and the great all-over works by Mark Rothko and Sam Francis. The show dedicated to Vallotton in 1991–93 (New Haven, Houston, Indianapolis, Amsterdam, Lausanne) shone a light on the artist’s mature works and, in the process, his links with the German and Dutch movement Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) of the 1920s and 1930s, as well as with Edward Hopper.

As may be recalled, Surrealist André Breton – a great admirer of Arthur Rimbaud and Symbolism in general – was one of the first to rediscover Filiger. This dialogue between Post-Impressionism and contemporary art is more vibrant than ever today: in his preface to the 2013 exhibition ‘Félix Vallotton, le feu sous la glace’ (Paris, Amsterdam), Guy Cogeval brilliantly compared Vallotton’s staged settings with those of Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock, affinities that had already been sketched out in the exhibition ‘Alfred Hitchcock and Art: Fatal Coincidences’ at the Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal. In spring 2013, the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne offered a prolific comparison between the American artist Alex Katz and Vallotton. In 2015–16, contemporary artist and film director Joann Sfar was invited by the Musée d’Orsay to present 60 paintings and 60 drawings inspired by Bonnard. To accompany his drawings in the catalogue, Sfar authored a text in which, with extreme pertinence, he questioned the relationship between Bonnard – and, by extension, every artist – and his models, the body, desires and figuration. He also examined the profound and almost philosophical seriousness of Bonnard’s painting, in that it confronts viewers with the mundanities of everyday life, obliging them to put their own existence into perspective. Right down to its semi-circular format, Bonnard’s fan design La Famille Terrasse is a presentation of the ages of life, a characteristic theme

in nineteenth-century popular imagery. In just a few pages, Sfar offers a surprising view of Bonnard, as perhaps only a contemporary artist would be able to. In fact, while the Nabis’ place in art history has become as self-evident as those of the famous ‘-isms’ (Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism), the group’s aesthetic, their vision of the world and their analysis of human relationships are constantly being examined in contemporary art. It is a history that is very much alive and forward-looking.

1868–1941

Six years after arriving in Paris in 1878, Émile Bernard joined the free studio run by Fernand Cormon (1845–1924), where he made friends with artists Henri de ToulouseLautrec and Louis Anquetin. After just two years, in 1886, he was asked to leave, as his use of the pointillist technique went against Cormon’s teaching. In 1887, Bernard went to Brittany with Anquetin, and met Émile Schuffenecker in Concarneau the following year. He then went to Pont-Aven where he became enthralled by the ideas of Paul Gauguin, and introduced Gauguin to zincography.

In 1886, Bernard joined the Mercure de France as an art critic and in 1892 wrote a complimentary article on Paul Cézanne. In 1907, he published their correspondence. In 1888, Bernard’s work was exhibited for the first time, alongside that of Toulouse-Lautrec, in a show held at the Grand Restaurant-Bouillon; he exhibited again that same year at the Salon des Indépendants. Rejected from the Salon d’Automne in 1889, he was one of the artists who exhibited at the Café Volpini on the fringe of the Exposition Universelle. He was later included in the exhibition at the Café des Arts with the group of artists he had met in Pont-Aven. Bernard definitively broke off his relations with Gauguin in 1891, and a year later he decided to mount a first retrospective of the work of his great friend Vincent van Gogh, who had died two years earlier. Supported by his patron Antoine de la Rochefoucauld, Bernard spent the years 1893 and 1904 travelling in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Palestine and Egypt.

On returning to France in 1905, he founded the journal Rénovation Esthétique, which he edited until 1910. Like Anquetin, Bernard encouraged his colleagues to return to both the classicism of the Old Masters (Raphael, Velázquez, Poussin) and the medieval technique of woodcuts. Bernard died in 1941, having published the rest of his correspondence with Cézanne (1925) and an essay entitled ‘La connaissance de l’art’ (1935).

c. 1887 oil on canvas

14 5/8 × 18 in / 37 × 45.5 cm

Gabriel-Albert Aurier (directly from the artist); thence by descent to Suzanne Aurier-Williame (his wife)

Estate of Suzanne Aurier-Williame, Nohant-par-Bruère

Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris: 10 December 2016 (lot no. 20)

Private Collection

Émile Bernard, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Jean-Jacques Luthi, Side Editions, Paris, 1982, no. 69 (repro.)

Émile Bernard, Sa vie, son Œuvre. Catalogue raisonné, Jean-Jacques Luthi and Israël Armand, Editions des cat.s raisonnés, Paris, 2014, no. 89, p. 151 (repro.)

This painting is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by Béatrice Recchi Altarriba.

1887 oil on canvas 16 1/8 × 12 3/4 in / 41 × 32.3 cm

Gabriel-Albert Aurier (directly from the artist); thence by descent to Suzanne Aurier-Williame (his wife)

Estate of Suzanne Aurier-Williame, Nohant-par-Bruère

Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris: 10 December 2016 (lot no. 21)

Private Collection

‘Émile Bernard 1868–1941. A pioneer of Modern Art’, Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim, 12 May – 5 August 1990; touring to Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 24 August – 4 November 1990, cat. no. 38, pp. 170–71 (repro. in colour)

Émile Bernard, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Jean-Jacques Luthi, Side Editions, Paris, 1982, no. 62 (repro.)

Émile Bernard, Sa vie, son Œuvre. Catalogue raisonné, Jean-Jacques Luthi and Israël Armand, Editions des cat.s raisonnés, Paris, 2014, no. 89, p. 149 (repro.)

This painting is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by Béatrice Recchi Altarriba.

1867–1947

Born into a middle-class family, and a brilliant pupil at secondary school, Pierre Bonnard studied law in 1886–87 while also attending the Académie Julian. It was there he met Maurice Denis, Gabriel Ibels, Paul Ranson and Paul Sérusier. After a brief spell at the École des Arts Décoratifs, followed by the Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he met Édouard Vuillard and Ker-Xavier Roussel, Bonnard turned against his family’s wishes and took up painting full time. In 1889 he formed the Nabi group with these six fellow-artists and designed his first poster for FranceChampagne. In 1891, he exhibited for the first time at the Salon des Indépendants and at the gallery Le Barc de Boutteville; in 1896 he had his first solo exhibition at the Durand-Ruel gallery.

Very active in the theatre world, Bonnard produced illustrations for André Antoine’s Théâtre-Libre, then for Lugné-Poe’s Théâtre de l’Œuvre. Bonnard then became close with Alfred Jarry and collaborated on the sets for Jarry’s play Ubu Roi in 1896, followed by the Almanach du père Ubu illustré in 1901. He worked as a preferred illustrator for La Revue blanche until 1903 from the time of its creation by Thadée Natanson and his two brothers in 1889; he also produced prints commissioned by Ambroise Vollard for the album of Peintres Graveurs (1896), for Jules Renard’s Les Histoires naturelles in 1904, and André Gide’s Prométhée mal enchaîné (1920).

In 1912, Bonnard moved to Vernonnet, near Giverny, and frequently visited his elder colleague Claude Monet, returning to a more Impressionist style just as Cubism was prevailing. A year later, he went to Hamburg with Vuillard at the invitation of the historian Alfred Lichtwark, before experiencing a period of artistic crisis during the First World War. In 1924, a major retrospective of his work was held at the Galerie Druet. Two years later, Bonnard bought a villa in Le Cannet, where he lived until his death in 1947.

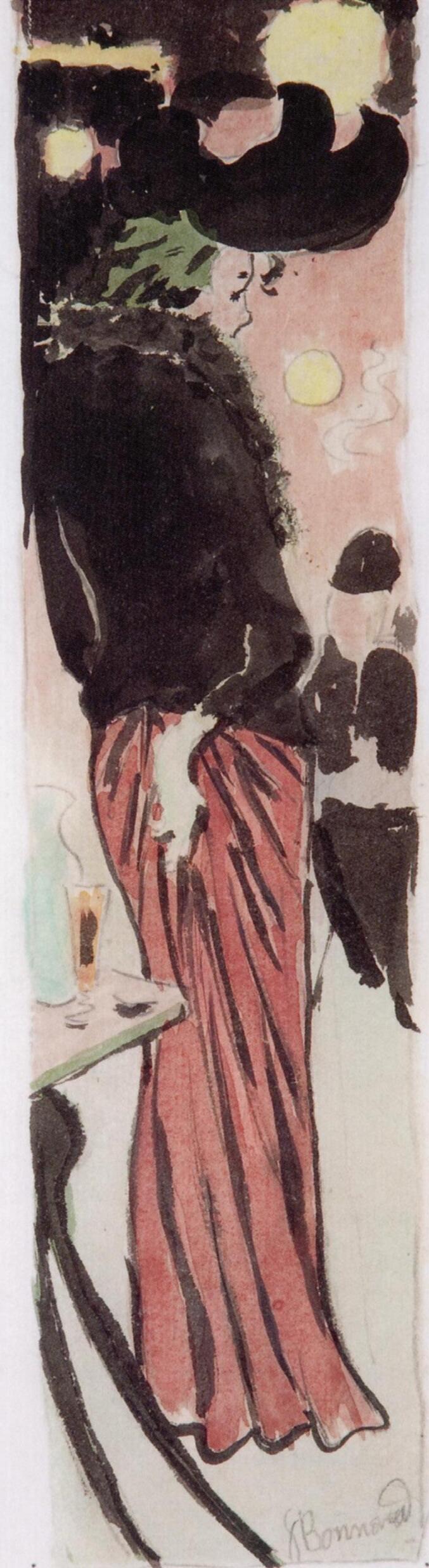

c. 1890

watercolour, Indian ink and pencil on paper 12 1/2 × 4 1/2 in / 31.6 × 11.5 cm

Gabriel-Albert Aurier (directly from the artist)

Succession Gabriel-Albert Aurier

Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris: 10 December 2016 (lot no. 13)

Private Collection

This artwork is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity issued in Paris by Bernheim-Jeune on 12 January 2018 and signed by Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Floriane Dauberville. It is registered in the Bernheim-Jeune archive under number 218-01 12 B [titled ‘Femme au cabaret’].

Once part of the highly discerning collection of art critic Gabriel-Albert Aurier (see his biography on p. 221), this drawing reveals a little-known and surprising aspect of Bonnard’s production: his depiction of Parisian cafés during La Belle Époque.

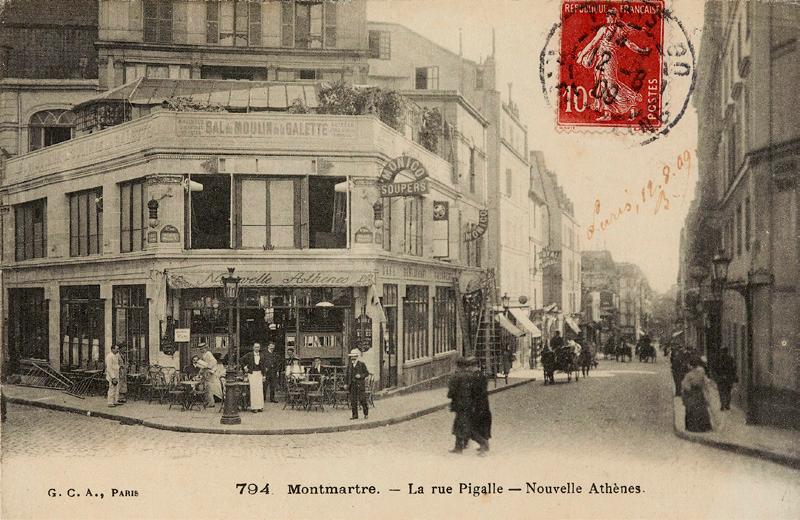

Celebrated in literature and painting in the late 19th century, French cafés were fundamental places of leisure and conviviality, lavishly described by writers – for example, the Café Riche on the capital’s grand boulevards, not far from the Paris Opéra, which Émile Zola used as a setting for several scenes in his novel La Curée (1871), as did Guy de Maupassant for certain chapters in Bel Ami (1885). Cafés were also meeting places for writers and painters: Charles Baudelaire was a regular at the Momus, Paul Verlaine at the François Ier, and Zola at the Café Guerbois, which was also frequented by Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro. Soon, guides were published listing the different cafés according to their specific characteristics: Auguste Lepage published Les Cafés politiques et littéraires de Paris in 1874, followed by Les Dîners artistiques et littéraires de Paris in 1884. Cafés were a favourite motif among the Impressionists: see L’Absinthe (1876) by Degas (Paris, Musée d’Orsay) and La Prune (1878) by Manet (Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art). Artists even exhibited in cafés, for instance Van Gogh at Le Tambourin, run by Agostina Segatori. It should be mentioned that the first public commercial screening of a film was held by the Lumière brothers at the Grand Café on 28 December 1895. In 1890–91, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis and Aurélien

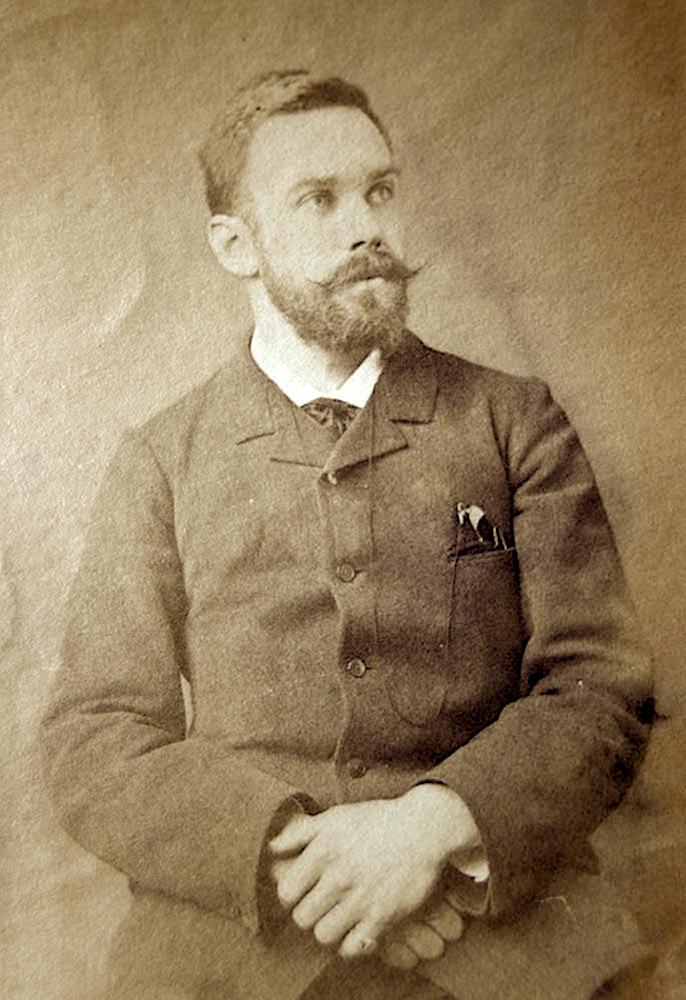

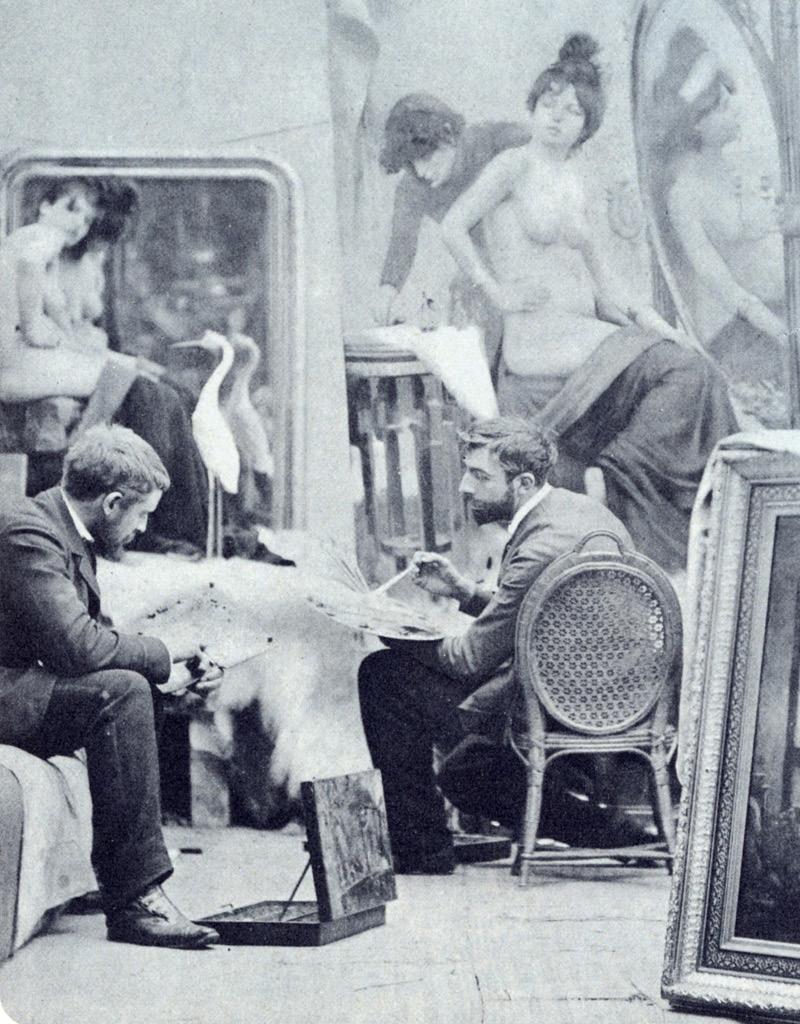

Lugné-Poe shared a studio at 28 Rue Pigalle [1], at the foot of the Butte Montmartre, a short stroll from the Café de la Nouvelle Athènes, the meeting place of the Impressionists. The café was also central to a number of avant-garde cabarets: Jehan Sarrazin’s Le Divan Japonais, Rodolphe Salis’s Le Chat Noir, Aristide Bruant’s Le Mirliton, and, of course, Zidler and Oller’s Moulin Rouge, for which Bonnard designed a poster. Although Bonnard produced several paintings of café-concerts, such as Le Jardin de Paris (1896) (Hays Collection, promised to the Musée d’Orsay), very few works, with the exception of Au Bar (1892) [2], depict cafés. This specificity and originality are indisputably the most important aspects of this watercolour.

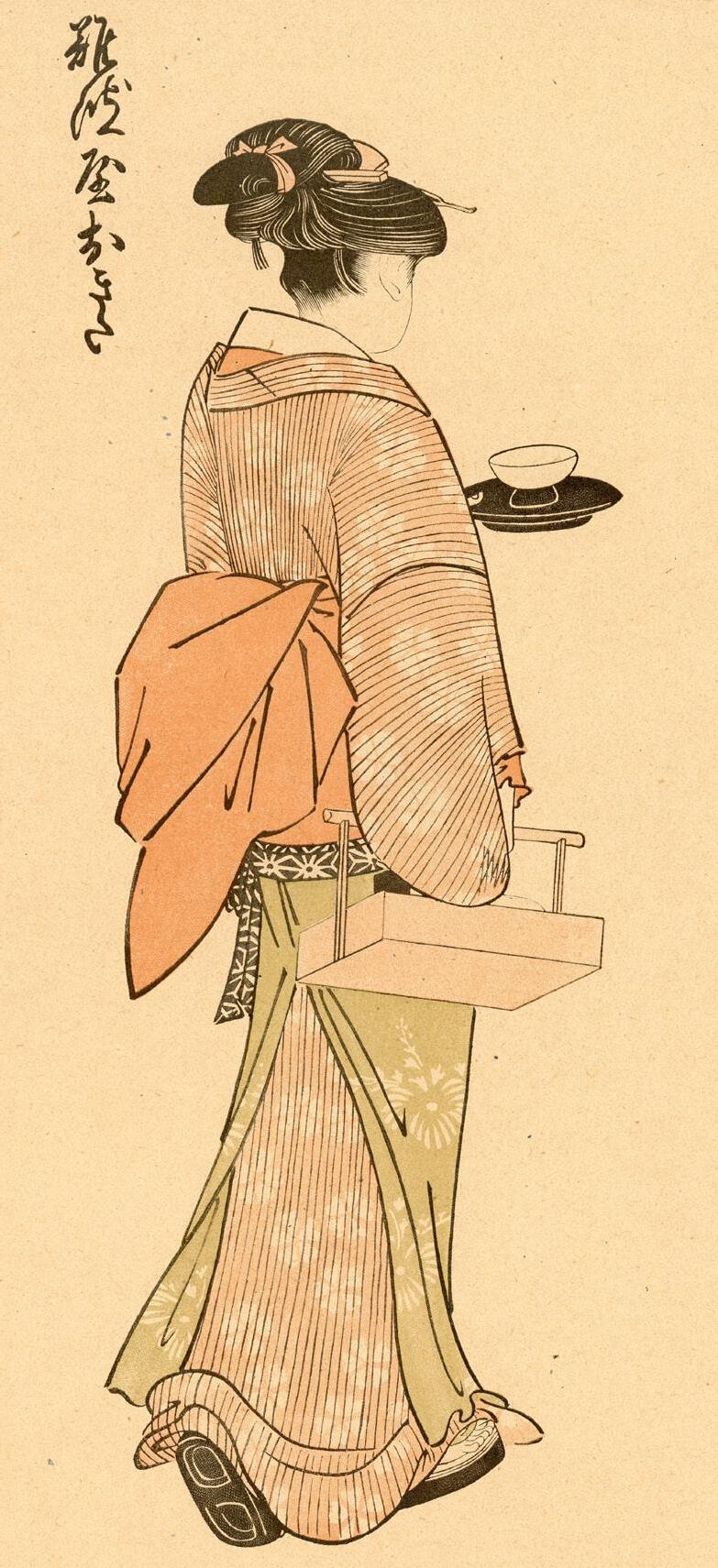

What is most striking about Au café (c. 1890) [p. 20], however, is its very tall and narrow format, which raises questions about its purpose. It could have been a preparatory work for a folding screen, of which we see only one panel here, a study for an easel painting, or even a decorative strip to be used in a magazine. Regardless, its kakemono format attests

to the influence of Japanese prints, enthusiastically discovered by the Nabis in the art review Le Japon artistique (1888–91) [3], published by Siegfried Bing.

Originally from Hamburg, Bing had come to Paris to set up a branch of his family’s company, which specialised in importing objects from the Far East. To open his new gallery, La Maison de L’Art Nouveau, he even commissioned Bonnard and his Nabi friends to design cartoons for a series of stainedglass windows to be made by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Bonnard’s infatuation with Japanese

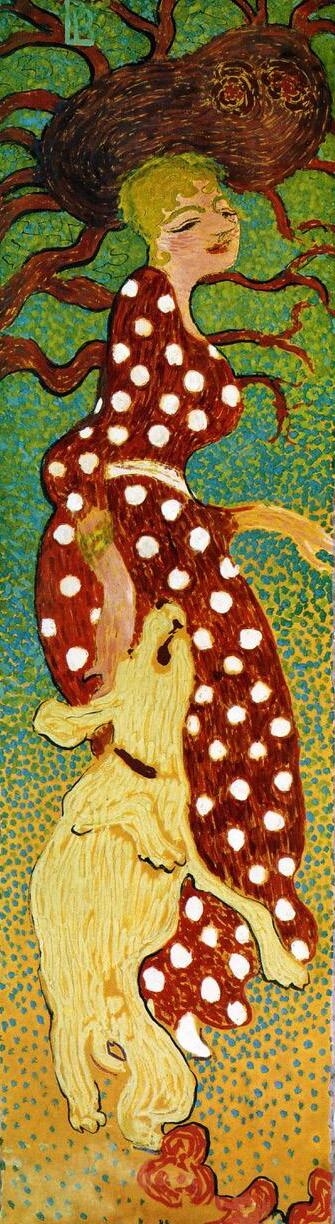

chirimen-e (prints on a kind of crepe paper) was confirmed by his visit to the large exhibition of Japanese prints, fabrics, and objects at the École des Beaux-Arts in spring 1890. Bonnard became, as his friends affectionately called him, the ‘Nabi japonard’.1 From that time on, he had a fondness for the kakemono format, which prompted him to use daring graphic designs enhanced by the two-dimensionality of Japanese prints. For example, consider Femme à la robe à pois (1891) [4], one panel of the screen Quatre Femmes au jardin (Paris, Musée d’Orsay), which Bonnard dismantled in 1892 to transform its sections into easel paintings. The female figure in Au café receives similar treatment, shown in profile and given an identical hat that extends almost disproportionately forward in curves that echo the cast-iron legs of the café table.

Bonnard did not treat this figure purely graphically, however attractive the idea may have been. There are several details that suggest a more complex interpretation of the scene: the feathered boa around her neck (an accessory also seen in some of ToulouseLautrec’s sketches of demi-mondaines), the woman’s right hand strangely contorted behind her back as it seems to reach for a glass, and the position of the man facing her, shown seated in this version but standing in another [5]. Gradually, the mild and rather superficial café scenes painted by Jean Béraud made way for a coarser reality, revealing the harsher aspects of life in Paris in the 1900s. This is almost the world of Jean-Louis Forain, but without that artist’s malevolent gaze. Bonnard did not depict this young woman without wishing to illustrate something more than what we see. In fact, cafés were looked upon with mistrust and suspicion by the authorities throughout the 19th century, with Balzac referring to them as the ‘people’s parliaments’ and Gambetta viewing them as ‘salons of democracy’. By the end of the century, alcoholism and immorality were the greatest issues of concern. In L’Assommoir (1877), Émile Zola viewed bars as dens of iniquity, while Alfred Carel, in Les Brasseries à femmes (1884), and, even more explicitly,

Ernest Guérin, in La brasserie, une plaie sociale (1891), labelled them places of debauchery and possible sexual soliciting. Considered in this context, the respective roles of the man in the bowler hat (indicative of his modest background) and the woman facing him directly, for a ‘woman of the world,’ suggest a dynamic worth exploring. It raises the question of who is attempting to seduce whom. Their relationship may develop into either a sentimental or a commercial affair. A humanist like his friend Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard makes no judgement: he observes, illustrates the scene, and leaves the interpretation open to the viewer.

1. With the meaning of ‘Japanese] Nabi’ but based on a pun on the sound of his surname.

[1]. Postcard, Paris, Le Café de la Nouvelle Athènes et la rue Pigalle

[2]. Pierre Bonnard, Au Bar (c. 1892), oil on card, 23 × 19 cm (private collection)

[3]. Utamaro, Serving Girl in an Inn, published in Siegfried Bing, La Japon artistique, no. 21 (January 1890), pl. Baa

[4]. Bonnard, Femme à la robe à pois (1891) (Paris, Musée d’Orsay), from his Quatre femmes au jardin (1891), distemper on canvas, 160.3 × 48 cm (Paris, Musée d’Orsay)

[5]. Bonnard, Au café (1890), pen and ink, brush and watercolour on paper, 28.7 × 6.7 cm (private collection), reproduced in the catalogue of the exhibition ‘Bonnard, Magier der Farbe’, Wuppertal, Von der Heydt-Museum, 14 September 2010 – 30 January 2011, p. 148

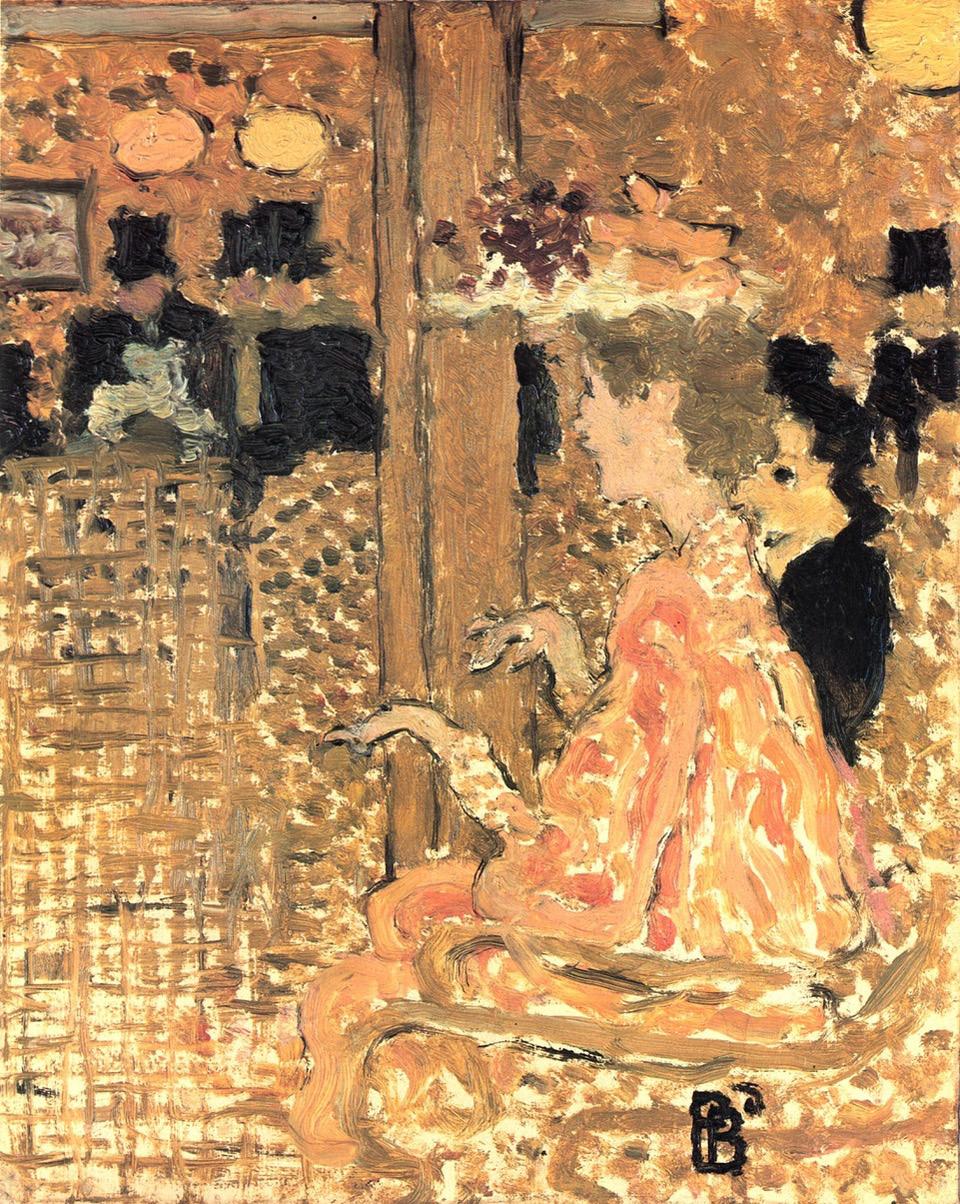

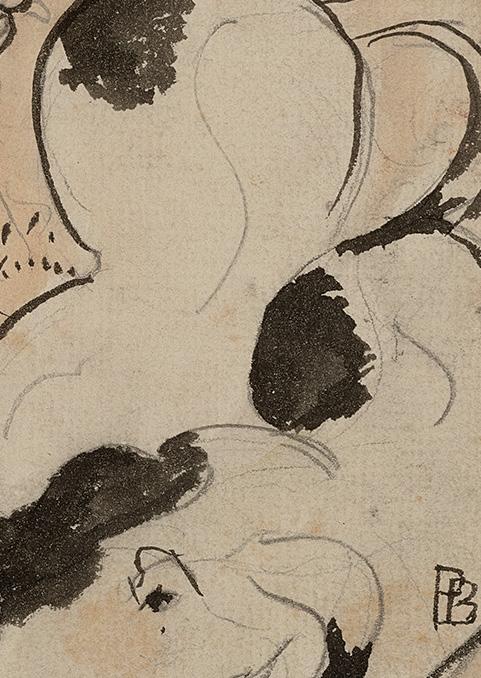

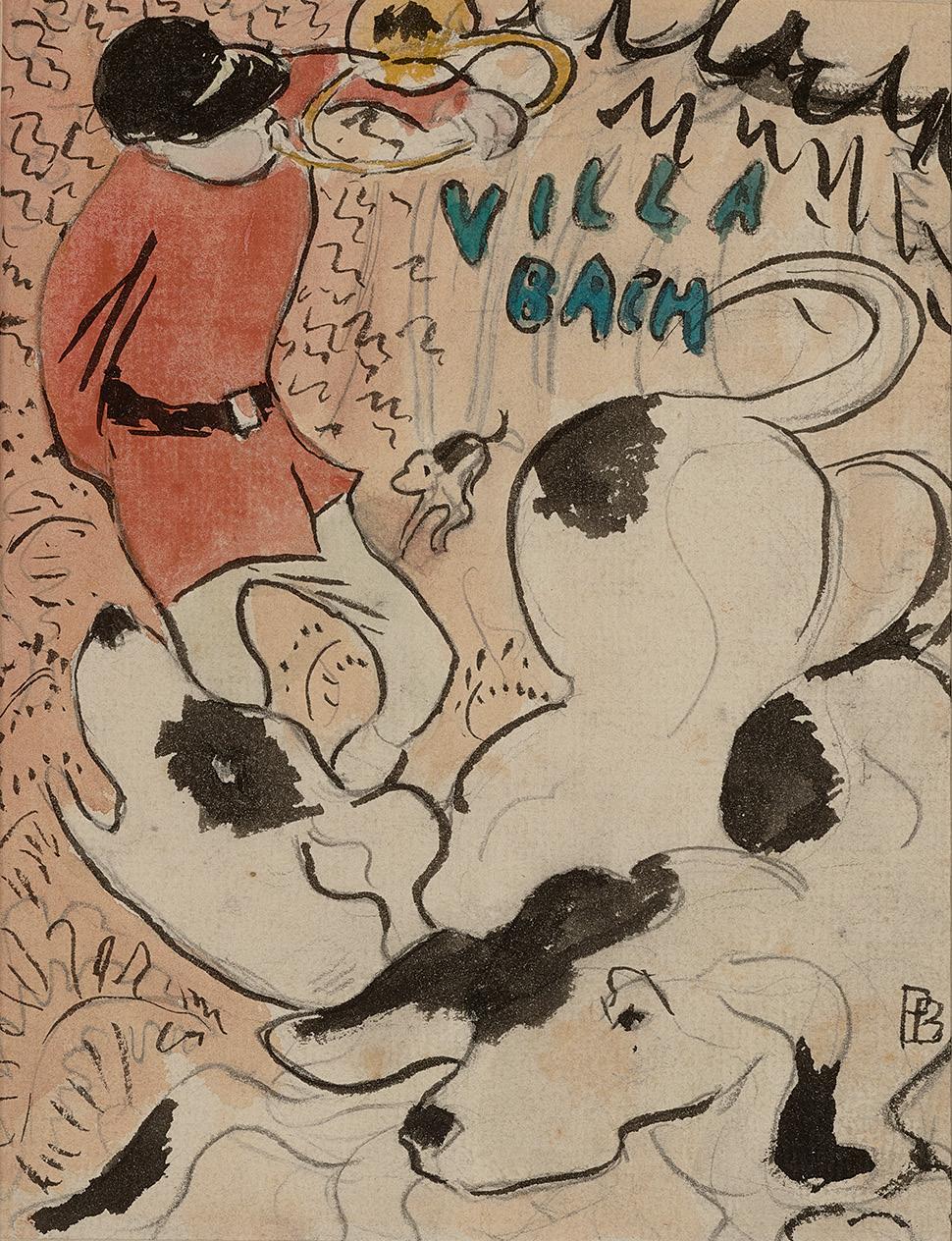

1890–91

watercolour, Indian ink and pencil on paper

6 3/8 × 5 in / 16 × 12.7 cm

initialled lower right ‘PB’

Gabriel-Albert Aurier (directly from the artist)

Succession Gabriel-Albert Aurier

Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris: 10 December 2016 (lot no. 10)

Private Collection

This artwork is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity issued in Paris by Bernheim-Jeune on 16 January 2018 and signed by Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Floriane Dauberville. It is registered in the Bernheim-Jeune archive under no. 218-01 16B.

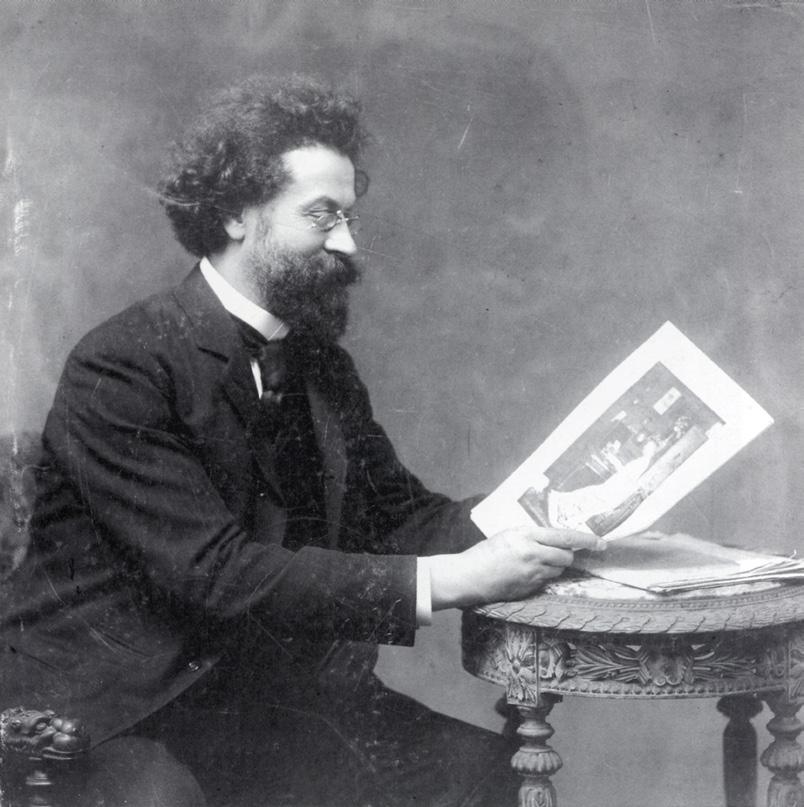

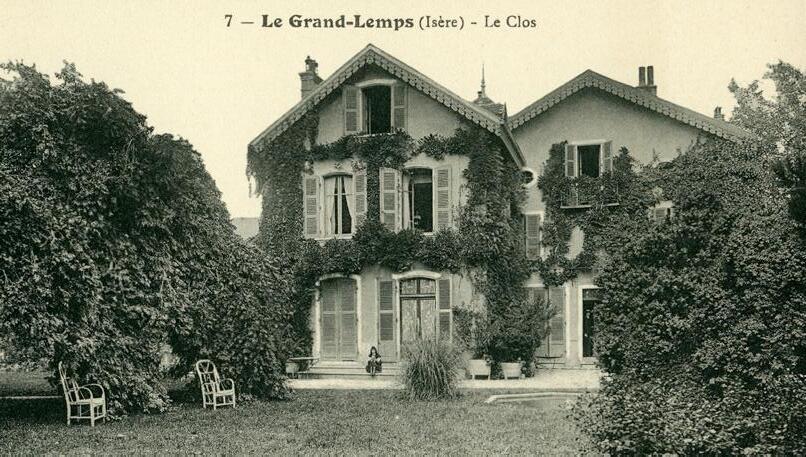

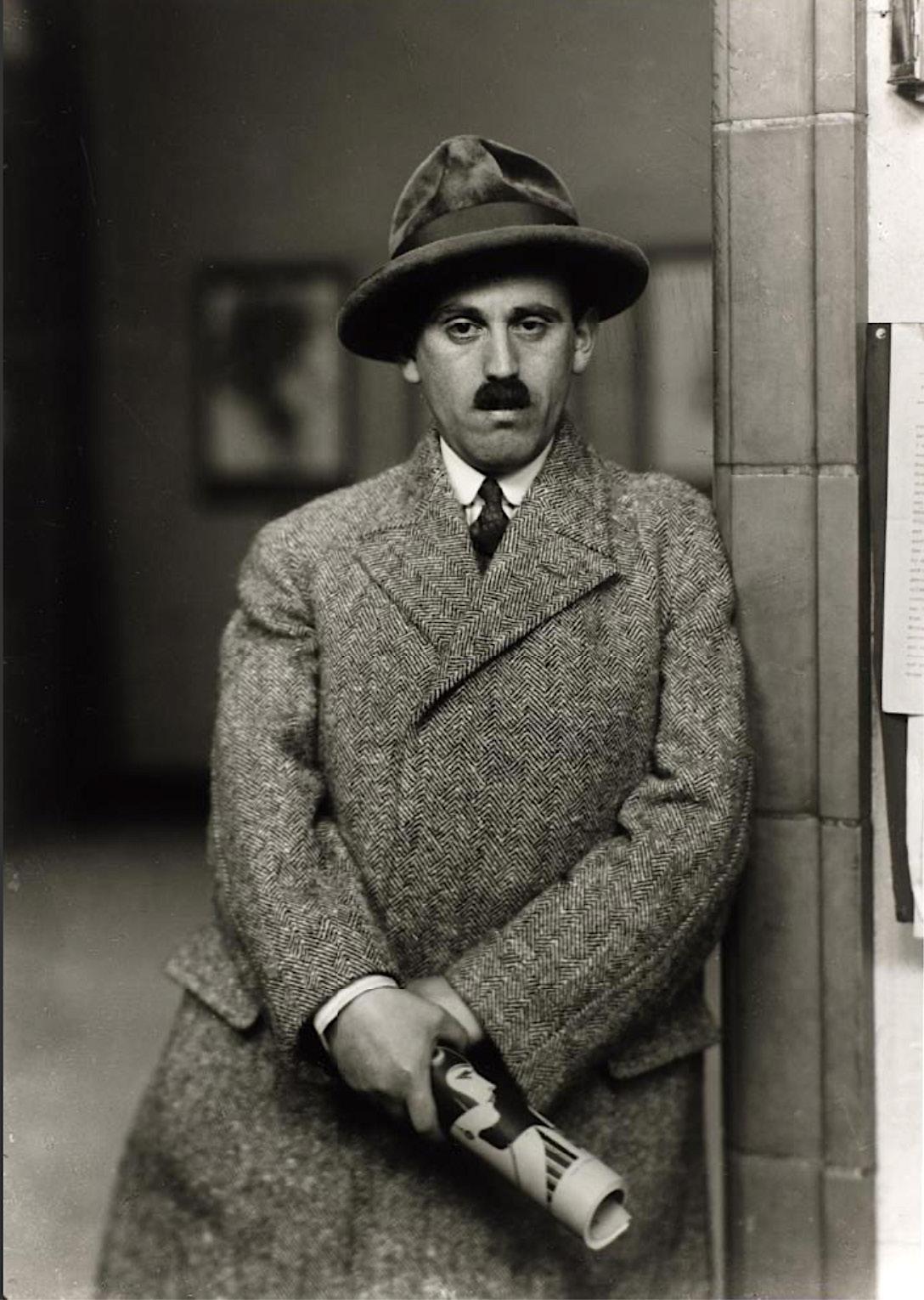

While doing his military service in Grenoble from November 1887, a young musician named Claude Terrasse (1867–1923) [1] met Charles Bonnard, with whom he quickly became friends. Charles was the brother of Pierre Bonnard, who was then a pupil at the Lycée Fontanes (later called Condorcet), alongside fellow students Édouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis. During 1888, Terrasse, a future composer, was invited on several occasions to Le Clos [2], the Bonnards’ family home in Le Grand-Lemps, near Grenoble, where he met Charles and Pierre’s younger sister, Andrée Bonnard.

The pair met again in Paris in early 1889, and in September or October of the same year Terrasse left for Arcachon, where he had been offered the post of harmonics teacher at the Dominican-run Collège Saint-Elme. He held this position from 1889 to 1896.1 A lengthy correspondence followed between the suitor and Bonnard’s mother, Madame Frédéric Mertzdorff, during which the young musician increasingly declared his love for Andrée. After the couple’s wedding, celebrated on 24 September 1890 by the mayor of Le Grand-Lemps, they moved into the Villa Bach in Arcachon. Bonnard and Terrasse soon became close friends, and the artist portrayed the composer in several intimate paintings from 1891 onwards.

Located on Boulevard d’Haussez in the ‘summer city’ of Arcachon, the villa was close to the station, and thus offered all the amenities a young couple might need. Prompted by an overwhelming desire to draw, as a letter to his sister makes clear, Bonnard soon visited them: “I am also bringing a great deal of resignation to the streams of music that are bound to escape from the Villa Bach. But the Muse of Painting will be avenged, as I am bringing my box of colours with me, and streams of green, blue and yellow will flow in return”. This enthusiasm was also confirmed by Charles, who told Terrasse: “My brother has asked me to warn you not to rack your brains looking for distractions to last until Christmas. He’s going to bring his doodle box and while he’s capturing Arcachon beach on canvas, I’ll be collecting whales for lunch.” Contrary to what Charles thought, it was not the beaches that would immediately inspire Pierre, but the concerts that Terrasse held in his home.

Undoubtedly with the idea of illustrating concert programmes, Bonnard created a series of drawings for private use, with no known plans for publication.2 The motifs he chose for these unique works had no direct connection to music but reflected his imagination and abundant inventiveness: he depicted Claude and Andrée sitting tenderly together under foliage, a young woman playing a mandolin,3 a young woman sitting in an orchard,4 Andrée walking a dog,5 and even some skaters. What all these drawings have in common is their size (about 16 × 13 cm) and the fact that they all go by the title Villa Bach.

Villa Bach (La Chasse à courre) (1890–91) [p. 28] is an exception in this series, because although hunting as a subject is far removed from the concerts given at the Villa Bach, the horn offers a direct, though tongue-in-cheek reference to music. Here, Bonnard takes up a motif that he had used in an earlier drawing [3], but this time he transforms it radically. Instead of the stiffness of his youthful watercolour, he now prefers a Japanizing distortion of the outlines. Far from being anecdotal, these small graphic pieces allowed Bonnard to experiment for the benefit of future works; for example, the motif of leaping dogs, whose bodies, partly treated in reserve, i.e. leaving the paper visible, are created using a line drawn almost without lifting the pen. He reused this dynamic arrangement of forms in 1891/1892 in a watercolour with the title Femme avec un chien [4]. The series of drawings for the Villa Bach ended in 1892. Following the birth of their first child, Jean Terrasse, in May of that year, the couple moved to the Villa Bijou on Boulevard de la

Plage in Arcachon. Nonetheless, Bonnard did not stop collaborating with his brother-in-law. In 1893 together they published Petites Scènes familières, a series of scores for songs composed by Terrasse, with illustrations that had been started at the Villa Bach in 1891, and Le Petit Solfège illustré, intended to make learning music less dull for children.

It is important to note the significance of the relationship between Bonnard and GabrielAlbert Aurier, the first collector to own Villa Bach (La Chasse à courre) (1890–91). A poet

and art critic, Aurier came to own several works by Bonnard, including Au café (c. 1890) [p. 20]. Aurier (see p. 221) was an ardent defender of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and the Nabis, and, in particular, Bonnard. This is evident from the place of honour he gave the artist in his influential article on the Symbolists, published in the Revue Encyclopédique in April 1892, in which he reproduced one of Bonnard’s watercolours, whose whereabouts today are unknown [5].

1. See Philippe Cathé, Claude Terrasse (Paris: L’Hexaèdre, 2004), p. 23 ff.

2. 22 drawings today in Austin (TX ), in the collection of the Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas, and described Carlton Lake, Baudelaire to Beckett: A Century of French Art and Literature. A Cat. of Books, Manuscripts, and Related Material Drawn from the Collections of the Humanities Research Center (Austin, TX : Harry Ransom Humanities, 1976).

3. See Gilles Genty and Pierrette Vernon, Bonnard, inédits (Paris: Éditions Cercle d’Art, 2006), chapter ‘Bonnard et la musique’, p. 60 ff.

4. Reproduced in the catalogue of the exhibition Pierre Bonnard, Lisbon, Fundação Arpàd Szenes – Viera da Silva, 11 July – 30 September 2001, p. 21.

5. Reproduced in the catalogue of the exhibition Pierre Bonnard, The Graphic Art, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2 December 1989 – 4 February 1990, p. 44.

[1]. Unknown photographer, Claude Terrasse regardant une photographie (private collection)

[2]. Postcard, Le Grand-Lemps (Isère) – Le Clos

[3]. Pierre Bonnard, Départ pour la chasse (c. 1884), graphite, pen and ink, watercolour on paper, 16.5 × 11.7 cm (private collection)

[4]. Bonnard, Femme avec un chien (c. 1892), graphite, pen and ink, watercolour on paper, 25.7 × 18.4 cm (Springfield, Ma, Museum of Fine Arts)

[5]. Albert Aurier, “Les Symbolistes”, La Revue Encyclopédique (April 1892)

1892

oil on card affixed to panel 9 1/4 × 6 3/4 in / 23.5 × 17 cm

Collection Édouard Vuillard

Antoine Salomon, Paris

Madame Claude Dalsace, Paris

Galerie Berès, Paris

Private Collection, Switzerland

Private Collection

EXHIBITED

‘Au temps des Nabis’, Huguette Berès, Paris, 1990, cat. no. 14 (not repro.)

‘Pierre Bonnard’, Musée Maillol, Paris, 31 May – 9 October 2000, cat. no. 7, p. 24 (repro. in colour)

Bonnard. Catalogue Raisonne de l’oeuvre peint volume 4 et 1er supplement, Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bernheim–Jeune, Paris, 1974, no. 01728, p. 137 (repro. in b&w)

Pierre Bonnard, André Fermigier, Abrams, New York, p. 52 (repro.)

La peinture des Nabis, Claude Jeancolas, Editions Franck Van Wilder, Paris, 2002, p. 60 (repro. in colour p. 61)

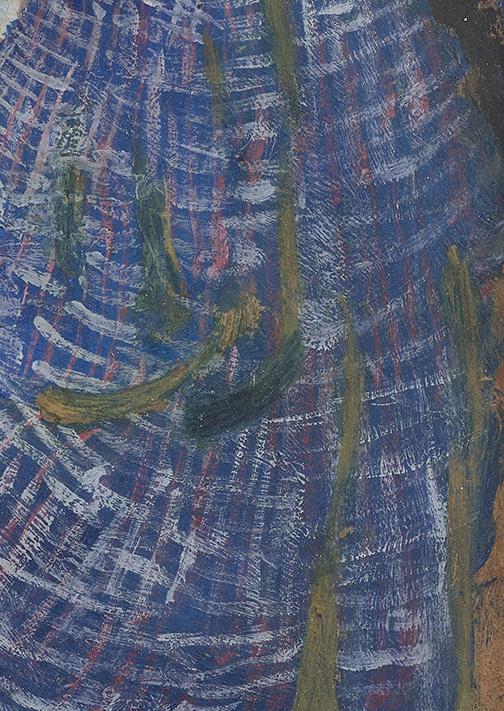

It is profoundly moving to follow the various stages in the creation of a work of art, from the artists’ initial idea to the final version. Exploring the many possibilities shaped by the artist’s imagination, their hesitations, and eventual decisions provides access to what still remains a mystery: what we call creation. This painting invites us to do just that.

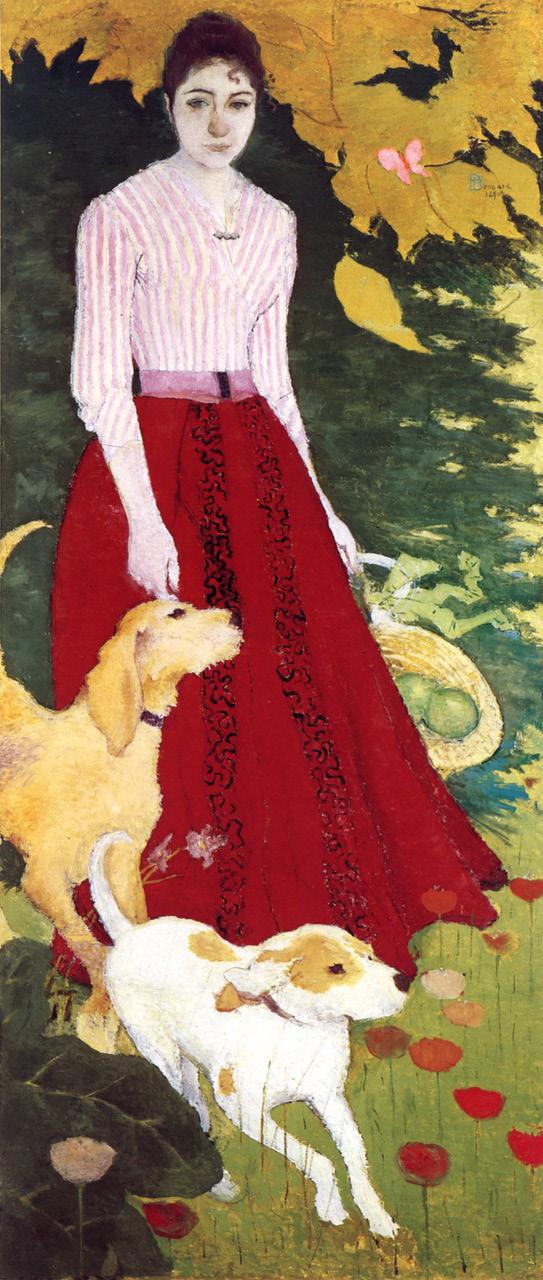

Bonnard’s relationship with his sister Andrée (1872–1923) [1], the figure in Étude pour ‘Le Corsage à carreaux’ c. 1892 [p. 34] was very similar to that between Édouard Vuillard and his sister Marie. Both sisters married artists: Marie became the wife of the painter Ker-Xavier Roussel, and Andrée married the composer and musician Claude Terrasse. Bonnard, who developed a genuine artistic dialogue with Terrasse, created many illustrations for him, particularly those for the concerts the musician gave at the Villa Bach in Arcachon [p. 30]. Both

women were also regularly portrayed by their respective brothers, making it possible to trace the evolution of their styles.

Bonnard usually depicted Andrée accompanied by her dogs, Bella and Ravageau,1 and even painted a portrait of the latter. Although he disrupted the conventional pictorial approach to full-length figures in Andrée Bonnard et ses chiens (1890) [2] by introducing movement, Bonnard remained uncertain about how to organise

the different elements in the space. There is a sense of hesitation between his volumetric representation of the two moving dogs and the contraction of perspectival depth, combined with the flat-tint treatment he applied to the upper section of the painting. It was during 1891 and 1892 that Bonnard truly found his style, as Étude pour ‘Le Corsage à carreaux’ demonstrates.

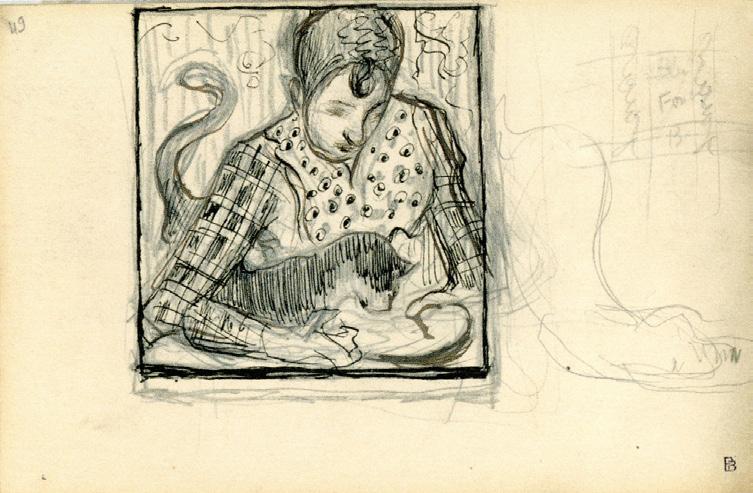

One of his earliest ideas can be seen in a sketchbook from 1890–91: on page 49 [3], Bonnard sketched his sister sitting at a table as a cat decides to join her. The distinctly Art Nouveau curves of the animal’s tail, and the way he created the motifs on the clothing, both attest to the extent of the continued influence on him of Japanese prints. It is worth noting that, in this initial sketch, Andrée is not wearing a red-and-white checked blouse but a blue-and-white checked dress with a red polka-dot jabot, which reappears in Femme au chien (1891) [4]. In the same sketchbook, this time on page 50, Bonnard also made a study for the latter painting. From the outset, he had planned to paint two portraits of Andrée: one with a cat, the other with a dog, one set indoors, the other outdoors.

The motif of the red-and-white checked blouse later appeared in the large watercolour Femme avec au chien (1891–92) [p. 31], in which Andrée is seen playing with a lively dog. Although Bonnard once again employed the idea of an elegant serpentine form to

depict the dog’s tail, this time he was much more adventurous in his use of formal solutions inspired by Japonisme. The publication of the review Le Japon artistique (1888–91) by Siegfried Bing, and the opening in the spring of 1890 of a large exhibition on Japanese art at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, clearly contributed to this shift.

The influence of Japanese art was also the subject of a leading article written by Bernard Dorival (1914–2003), then curator at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, in which he focused on the painting Le Corsage à carreaux when it entered the French national collections.2 Following Ursula Perruchi-Petri’s innovative research 3 and the seminal exhibition Japonisme (Paris, Grand Palais, 1988), Bonnard’s fascination with Japanese prints has been well documented. Like Claude Monet, Bonnard purchased original prints, collecting them more for their aesthetic value than for their rarity. The one by Utagawa Kuniyoshi [5] is a good example: it mattered little to the painter that it was just one part of a triptych because it suggested inventive decorative motifs. Perruchi-Petri recounts an anecdote shared by Professor Hans R. Hahnloser: when he asked Bonnard what he owed most to the Japanese, the artist replied, ‘The small checked patterns!’4

At the start of 1892, the definitive composition took shape: based on a drawing enhanced with watercolour [6], Bonnard returned to his idea of depicting Andrée, this time dressed in a uniform red-and-white checked blouse, eating at a table with her cat in front of her. The cat, now sitting up, seems eager to take part in the meal, as suggested by its wide-open eyes and a paw, sketched in pencil, boldly stretched towards a plate. Bonnard has given Andrée the pose she will adopt in the final painting, including her slightly off-kilter shoulders and the elegant curl of hair on her forehead. The large brown bottle on the right would later be replaced by a white carafe, which gives greater prominence to the young woman. The entire scene is bathed in a warm orange light, cast by a suspension lamp suggested by a few pencil lines at the top of the image. The most surprising aspect of this watercolour is the male figure sketched in on the far left, whose identity remains unknown: is he the composer Terrasse, or Bonnard himself? The painter still had to experiment with the effects that the colours would produce

when painted in oils. And it is precisely this fundamental step that is the subject of this particular painting.

Whereas in his earlier preparatory studies Bonnard had used flat tints and sinuous lines, at this point he began to construct his painting using a profusion of small touches of colour, like the Neo-Impressionists. Long undervalued by art historians, the influence of the technique developed by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac now appears to have been more significant than previously thought. It should not be forgotten that, under the aegis of the poet Gustave Kahn and the art critic Félix Fénéon, both of whom were great supporters of Neo-Impressionism, in 1891 the Nabis were included in an exhibition of Impressionist and Symbolist works in Saint-Germain-enLaye. From 1892 onwards, they also exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, created by Seurat and his friends in 1884 to defend their new approach to painting. Although Maurice Denis and Vuillard were the Nabis who most

admired Neo-Impressionism, Étude pour ‘Le Corsage à carreaux’ shows that Bonnard was not unaware of its formal potential: all the elements in the final composition vibrate with luminous colour, enhanced further by the small juxtaposed touches applied in the ferment of creation. He even used the support he had left almost bare, covered simply with a grey-white preparation, to represent certain motifs, such as Andrée’s face. What we see here is no longer the figurative use of colour but the formal logic developed by the Fauves. Furthermore, Bonnard executed his painting without the aid of any underlying drawing, like those painted by André Derain and Henri Matisse in the years 1904–05.

Bonnard then abandoned the peripheral motifs in the previous watercolour: the figure of the man disappeared, and the framing became tighter, which he bordered with a black line as though it could better restrain the expansion of the colours. Bonnard was acting here like a photographer who crops the shots on his contact sheet. More developed than the other motifs, the cat has almost become the focal point of the composition. The lines of Baudelaire’ s poem Le Chat come to mind:

Seraphic cat, singular cat, / In whom, as in an angel, all is / As subtle as harmonious! [...] A familiar figure in the place; / He presides, judges, inspires / Everything within his province; / Perhaps he is a fay, a god? 5

The last two versions of Le Corsage à carreaux [7 & 8, overleaf] follow the composition of the painting exhibited; in them, Bonnard narrowed the framing further, almost adopting the vertical format of the kakemono. Although he reverted to a more Japanizing style, playing with curves and counter-curves like a counterpoint musician, he retained the marvellous chromatic eloquence of the painting on display, which the Surrealist painter André Masson (1896–1987), who was very attentive to the work of the Nabis, later described as lyrical effusion. 6

1. On this point, see the catalogue for the exhibition Entre chiens & chats, Bonnard et l’animalité, Le Cannet, Musée Bonnard, 2 July – 6 November 2016.

2. Although the painting belonged to Andrée and Claude Terrasse, it was their son who sold it to the museum. See Bernard Dorival, ‘ Le Corsage à carreaux et les japonismes de Bonnard’, La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France, no. 1 (1969), pp. 22–24.

3. Ursula Perruchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1976).

4. Quoted in the cat. of the Bonnard exhibition, Zurich, Kunsthaus, 14 December 1984 – 10 March 1985, p. 82.

5. Charles Baudelaire, Les Fleurs du mal, Spleen et idéal, poem no. LI (1857). Eng. trans. by William Aggeler, The Flowers of Evil (Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954).

6. Quoted in Georges Charbonnier, Le Monologue du peintre, I (Paris: Julliard, 1959), pp. 190–91.

[1]. Unknown photographer, Andrée Bonnard (c. 1900) (private collection)

[2]. Pierre Bonnard, Andrée Bonnard et ses chiens (1890), oil on canvas, 180 × 80 cm (private collection)

[3]. Bonnard, Andrée et son chat, Carnet de dessins / folio no. 49 (1890–91), graphite, pen and ink on paper, 13.2 × 20 cm (private collection)

[4]. Bonnard, Femme au chien (1891), oil on canvas, 40.6 × 32.4 cm (Williamstown, Ma, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute)

[5]. Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Tokiwa Gozen, the Mistress of Minamoto no Yoshitone, in a Kabuki Scene, coloured woodcut, 35.5 × 24.5 cm (private collection, former Pierre Bonnard Collection)

[6]. Bonnard, Study for ‘Le Corsage à carreaux’ (1892), pencil, pen and ink, watercolour on paper (private collection)

[7]. Bonnard, Le Corsage à carreaux (1892), oil on canvas, 61 × 33 cm (Collection of Spencer and Marlene Hays, promised to the Musée d’Orsay)

[8]. Bonnard, Le Corsage à carreaux (1892), oil on canvas, 61 × 33 cm (Paris, Musée d’Orsay)

1892

watercolour on paper 11 1/2 × 21 5/8 in / 29 × 54.8 cm

signed centre left ‘P. BONNARD’; initialled and dated centre right ‘PB 1892’

Hôtel Rameau, Versailles: 2 December 1973 (lot no. 198)

Galerie André Romanet, Paris

Private Collection

Neret-Minet [Tessier & Sarrou], Paris: 21 November 2008 (lot no. 37)

Private Collection

EXHIBITED

‘Bonnard: Tekeningen en Akwarellen (Drawings and Watercolours)’, Singer Museum, Laren, The Netherlands, 1 May – 26 June 1977, cat. p. 11 (repro. in b&w) [titled ‘Le Sourire’]

Pierre Bonnard: The Graphic Art, John P. O’Neill, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1989, p. 213 (mentioned)

An everyday object and indispensable fashion accessory during La Belle Époque, the fan was also a personal belonging, a medium for lyrical beauty, and even a vehicle for declarations of love. In short, a fan was never insignificant.

In France, during the second half of the nineteenth century, fans received great attention. Baudelaire celebrated them in Le Peintre de la vie moderne (1869), and Maupassant asked, ‘Why shouldn’t poets take fans as a subject, just as painters are asked to colour them?’1 Within a few years, the fan had become a genuine social phenomenon. In 1882, the bibliophile and dandy Octave Uzanne2 traced its history since antiquity, while Gustave Fraipont3 offered advice on how to make your own. For painters, fans also became a way to decorate the background of paintings: consider Édouard Manet’s La Dame aux éventails, Nina de Callias (1874) (Paris, Musée d’Orsay) and Monet’s La Japonaise (1876) (Boston, Museum of Fine

Arts) [1]. Embracing Japonisme, painters Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Signac soon began producing fanshaped compositions.

Among the Nabis, fan-shaped drawings also reflected their genuine desire to promote the decorative arts. As Pierre Bonnard said: ‘Our generation has always pursued a relationship between art and life. At that time, I personally imagined a popular art with everyday applications: engravings, furniture, fans, screens.’4 Although Maurice Denis5 was the most prolific, Félix Vallotton and Bonnard also embraced these original mediums. Bonnard made a painted fan, Promeneurs et cavaliers, avenue du bois (1894) (whereabouts unknown), as well as several designs, including Femmes et fleurs (c. 1891) (Netherlands, Triton Foundation) and Les Lapins (1890–95) [2], the border of which poetically incorporates the name of his sister Andrée.

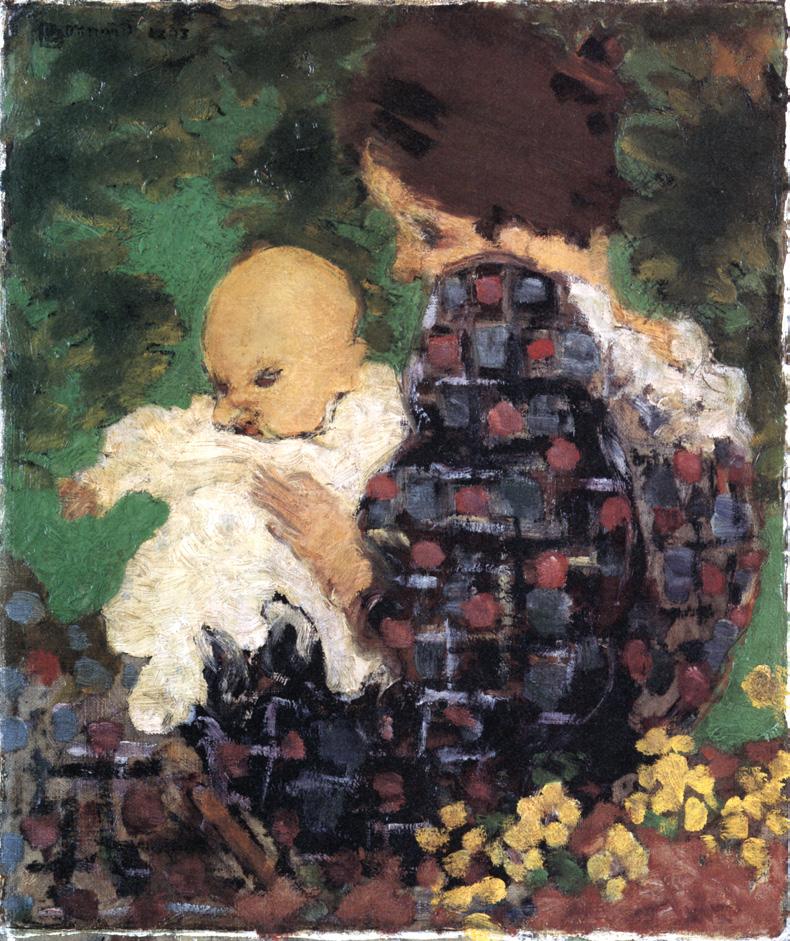

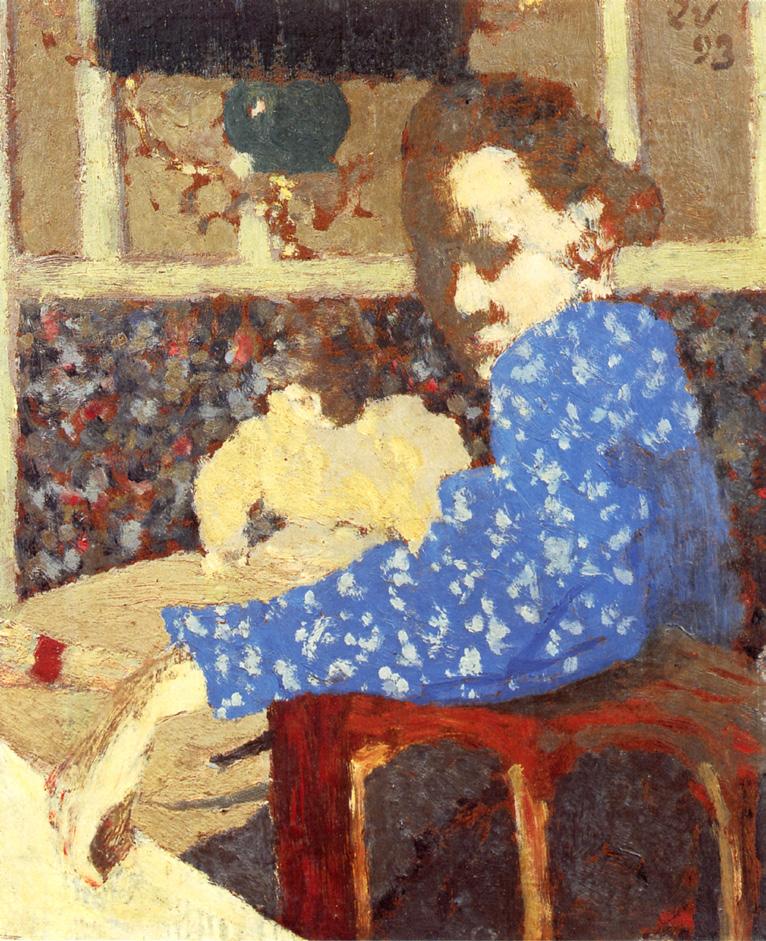

The most important aspect of Bonnard’s fan design lies in its iconography, which refers to the birth, on 6 May 1892, of Jean Terrasse, the first child of his sister Andrée and the musician Claude Terrasse [see Villa Bach (La Chasse à courre) (1890–91) p. 28]. Thrilled for his sister, Bonnard painted her numerous times in 1892 and 1893, as seen in Madame Claude Terrasse et son fils Jean (1893) [3]. For Bonnard, who was experiencing the emotional turmoil of a thwarted love affair with his cousin Berthe Schaedlin, the great love of his youth, this motif likely provided a welcome distraction from his distress.

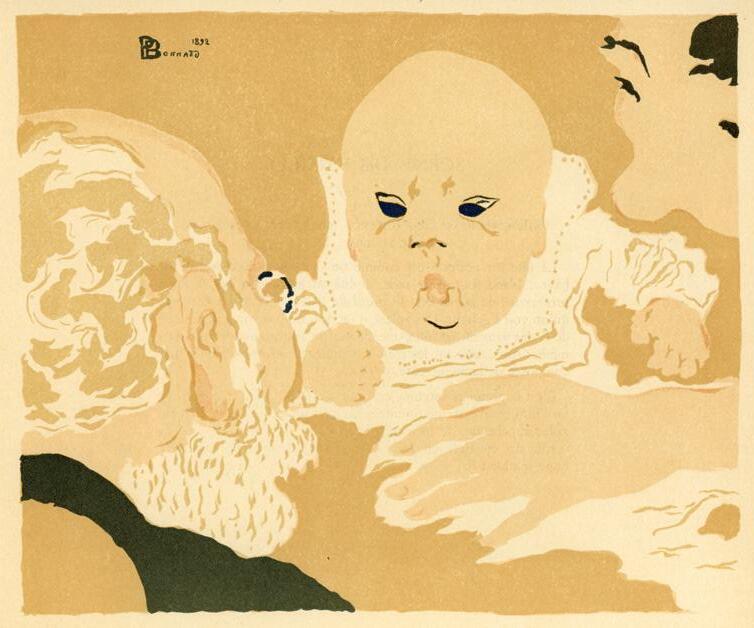

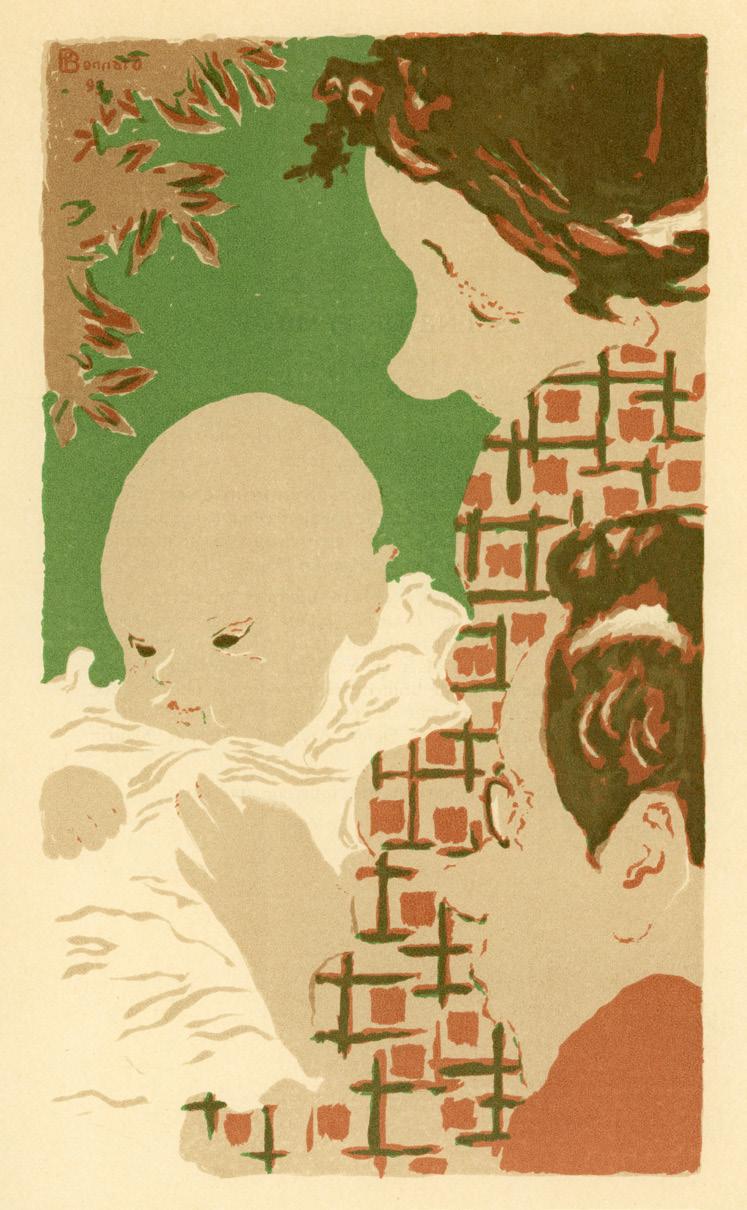

Both emotionally and artistically, family played a central role in Bonnard’s early

works.6 He frequently addressed the motif of mother and child – often with sacred overtones – across various media, including two lithographs from 1892 and 1893, one in horizontal format [4], the other vertical [5]. Regarding the first, Claude Roger-Marx, son of the art critic and collector Roger Marx, understood Bonnard’s graphic intent:

The baby’s head is like a sugar egg placed on the white bib. The same pink is used for the protective hand of the mother and the profile of the white-bearded grandfather on the left. Here and there, flat tints of Japanese black suggest almond-shaped eyes, a lock of hair, a jacket, and pince-nez. The same tones, uniting the three figures, confirm that they are made from the same clay.7

In the fan design, a second version of which is known8, where the only difference lies in a mottling of red spots on Andrée’s blouse, Bonnard employs tight framing, a very close viewpoint, and flat tints. The extreme proximity of the viewer to the figures distorts their outlines and forces us to view the scene through the eyes of a small child, who has little understanding of space.

Aside from stylistic similarities, comparing these works reveals that Bonnard alters the male figure in each: in the horizontal lithograph, he portrays Eugène, the baby’s maternal grandfather, while in the vertical lithograph, he depicts himself. In La Famille

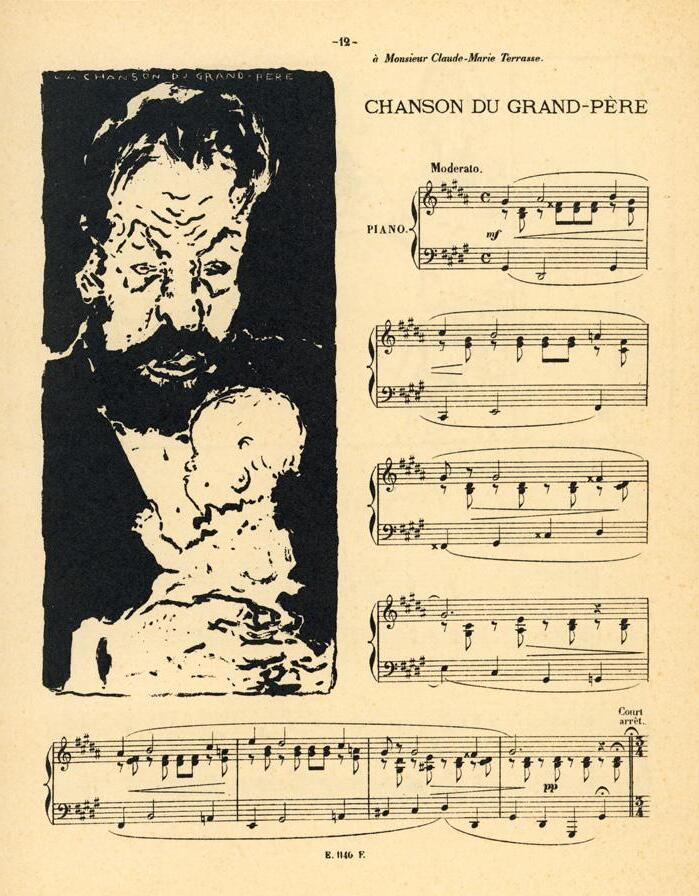

Terrasse (c. 1892) [p. 43], Bonnard’s grandfather, Claude-Marie Terrasse, can be easily identified.

The latter’s rather clumsy gestures toward the child are conveyed by the artist, whose depiction of the hand is almost caricatural. Bonnard references Claude-Marie again in one of the plates he drew for Petites Scènes familières [6], a series of songs written by Franc-Nohain and set to music by Claude Terrasse. The plate dedicated to the grandfather bears the title Chanson du grand-père. Bonnard began the illustrations in 1891, while staying at the Villa Bach; he completed them in 1892; they were published in 1893

In what seems like an ode to family joy, Eugène and Pierre, along with Claude-Marie, are shown as Three Wise Men, each coming to pay their respects to Andrée and Jean. Victor Hugo’s beautiful words in Les Feuilles d’automne (1831) come to mind: ‘Lorsque l’enfant paraît, le cercle de famille / Applaudit à grand cris; son doux regard qui brille / Fait briller tous les yeux’9

1. Guy de Maupassant, ‘Poètes’, Gil Blas, 7 November 1882.

2. Octave Uzanne, L’Éventail (Paris: Quantin, 1882).

3. Gustave Fraipont, L’Art de composer et de peindre L’Éventail, L’Écran, Le Paravent (Paris: Laurens, 1895).

4. Quoted by Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard, “la couleur agit” (Paris: Gallimard, 2000), p. 26.

5. The Musée Départemental Maurice Denis in SaintGermain-en-Laye has 18 fans or studies for fans in its collection. To these can be added designs in private hands.

6. See Véronique Serrano, ‘Maternités et scènes de famille chez Bonnard, Denis, Sérusier’, in the catalogue of the exhibition Enfances rêvées, Bonnard, les Nabis et l’enfance, Le Cannet, Musée Bonnard, 2 July – 6 November 2022, pp. 138–51.

7. Claude Roger-Marx, Bonnard lithographe (Monte-Carlo: André Sauret-Éditions du Livre, 1952), p. 18.

8. Pierre Bonnard, La Famille Terrasse (1892), crayon and watercolour, 26.7 × 51.1 cm (private collection), reproduced in the catalogue of the exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Graphic Art, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2 December 1989 – 4 February 1990, no. 15, fig. 89.

9. ‘When the child appears, the family circle / Applauds with loud cries; his gentle shining gaze / Brings a gleam to every eye’. Victor Hugo, Les Feuilles d’automne (Paris: Ollendorf, 1909), pp. 63–64.

[1]. Claude Monet, La Japonaise (1875–76), oil on canvas, 231.5 × 142 cm (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts)

[2]. Pierre Bonnard, Les Lapins (1890–95), crayon and brown ink on paper, 33.6 × 57.5 cm (Paris, Musée d’Orsay)

[3]. Bonnard, Madame Claude Terrasse et son fils Jean (1893), oil on canvas, 37 × 30 cm (New York, Alice Mason Collection)

[4]. Bonnard, Scène de famille [horizontal] (1892), 5-colour lithograph, 21 × 26 cm (private collection)

[5]. Bonnard, Scène de famille [vertical] (1892), 4-colour lithograph, 18 × 31 cm (private collection)

[6]. Claude Terrasse (music), Pierre Bonnard (lithograph), Petites Scènes familières / La Chanson du grand-père (1893), black lithograph on paper (Paris: Éditions Fromont, 1893)

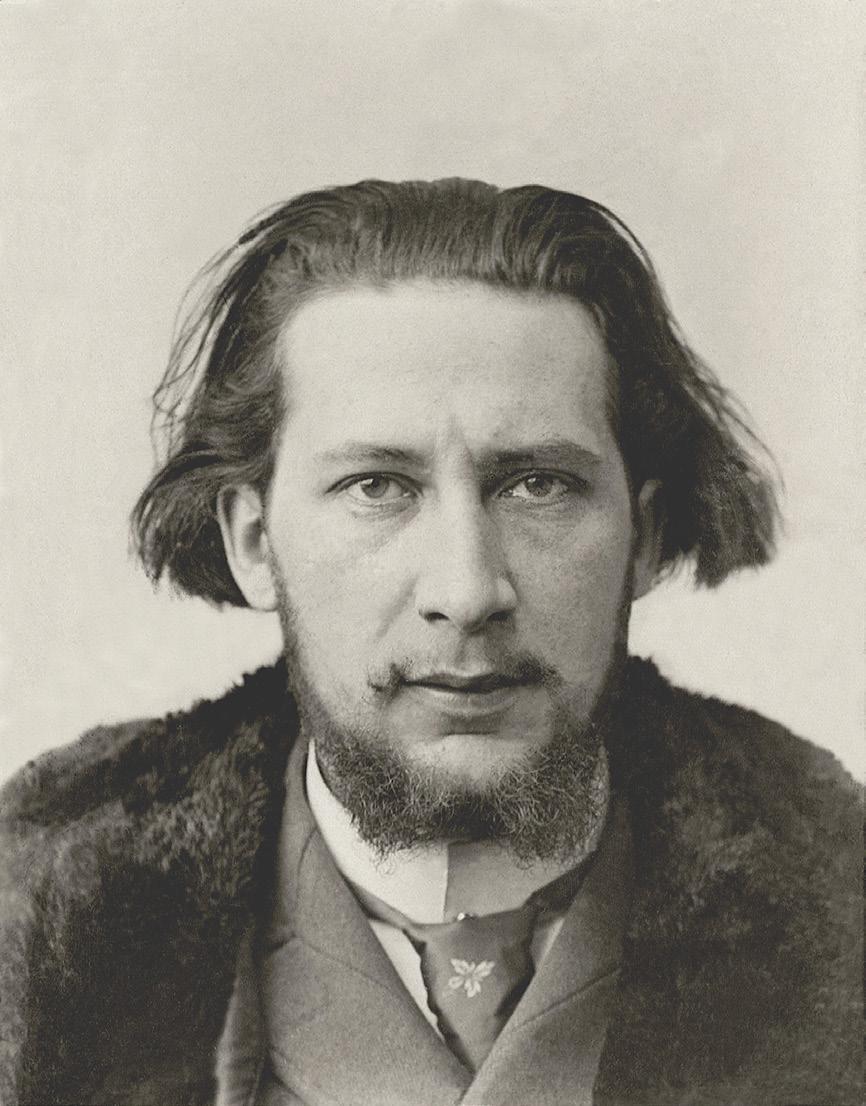

1870–1943

In 1888, Maurice Denis began studies at the Académie Julian with Ker-Xavier Roussel and Édouard Vuillard, both of whom he had met while at the Lycée Condorcet in Paris. Striking up friendships with Pierre Bonnard and Paul Ranson, the five formed the Nabi group the following year, for which Denis would be both the spokesman and the theoretician. On 23 and 30 August 1890 – the year he first took part in the Salon des Indépendants –Denis explained his credo in the review Art et Critique: ‘Remember that a painting – before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or an anecdote of some sort – is essentially a flat surface covered with colours, put together in a certain order’.

A champion of synthetism and mellow colours, the artist, nicknamed by his friends ‘the Nabi of the beautiful icons’, painted decorative panels for such influential people as the composer Ernest Chausson and the parliamentary deputy Denys Cochin, as his list of contacts had grown since he began frequenting the salon of the painter Henry Lerolle (1848–1925), whom he had met in 1891. There he met Renoir and Degas, as well as the authors Paul Claudel, Stéphane Mallarmé, André Gide and Paul Valéry, and the musicians Vincent d’Indy and Claude Debussy. Lerolle also introduced him to the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. In 1912, he converted a former hospital in Saint-Germainen-Laye into a studio he called Le Prieuré (The Priory), which he decorated on the theme of Saint Martha, in celebration of his wife Marthe, who died in 1919. That same year, Denis founded the Ateliers d’art sacré with the painter Georges Desvallières, where he continued the teaching vocation he had begun at the Académie Ranson in 1908.

Beginning in 1940, Denis sympathised with the Vichy regime and was consequently appointed chairman of the Comité d’organisation professionnelle des arts graphiques et plastiques. He passed away in 1943 after being involved in an accident with a lorry.

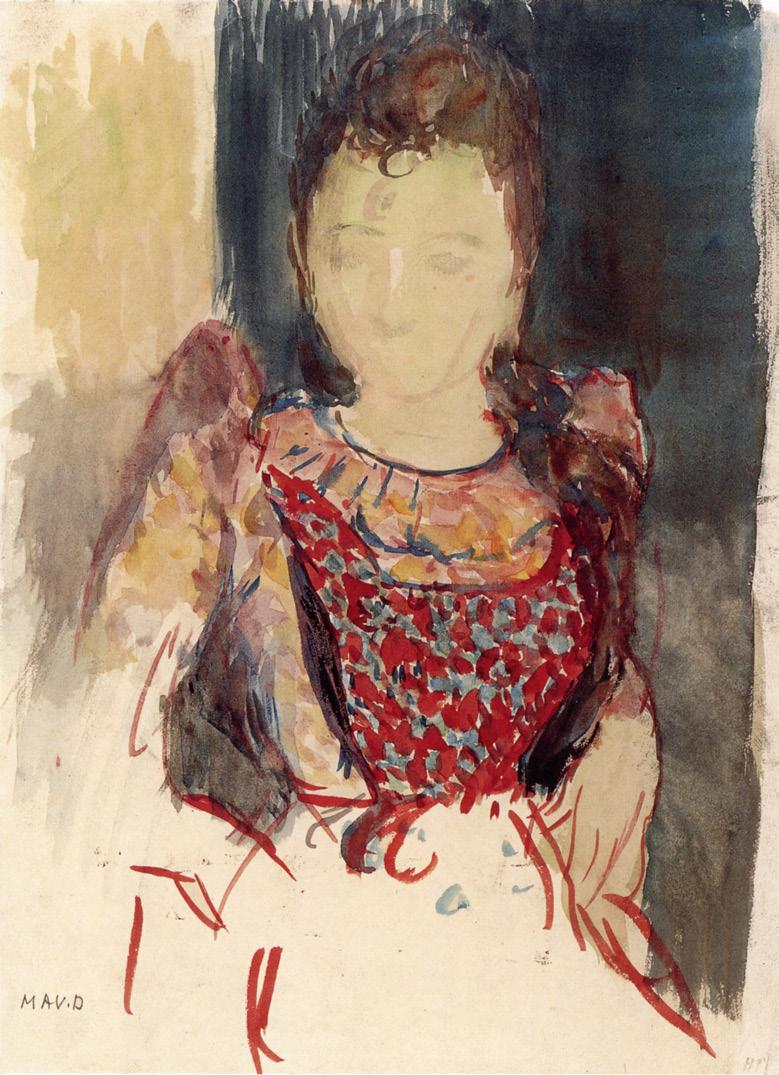

c. 1889–90 oil on card

11 5/8 × 7 1/8 in / 29.5 × 18 cm

stamped lower right with the artist’s round workshop monogram ‘MAUD’; stamped on reverse with the artist’s round workshop monogram ‘MAUD’ and certified by the artist’s daughter Madeleine Follain Denis.

Collection Madeleine Follain Denis (the artist’s daughter); thence by descent to Jean-Baptiste Denis (the artist’s grandson) and subsequent family collections

This work is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity, dated 30 August 2024 and signed by Claire Denis, the artist’s granddaughter.

c. 1892 oil on card

7 3/8 × 5 3/4 in / 18.5 × 14.5 cm

signed lower left with the artist initials ‘MAUD’; figurative sketch present on the underside of backboard

Collection Bernadette Denis (the artist’s daughter); thence by descent to JeanBaptiste Denis (the artist’s grandson) and subsequent family collections

‘Maurice Denis’, Galerie Berès, Paris, 4 June – 22 July 1992, no. 19 (repro. in b&w)

This work is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity, dated 30 August 2024 and signed by Claire Denis, the artist’s granddaughter.

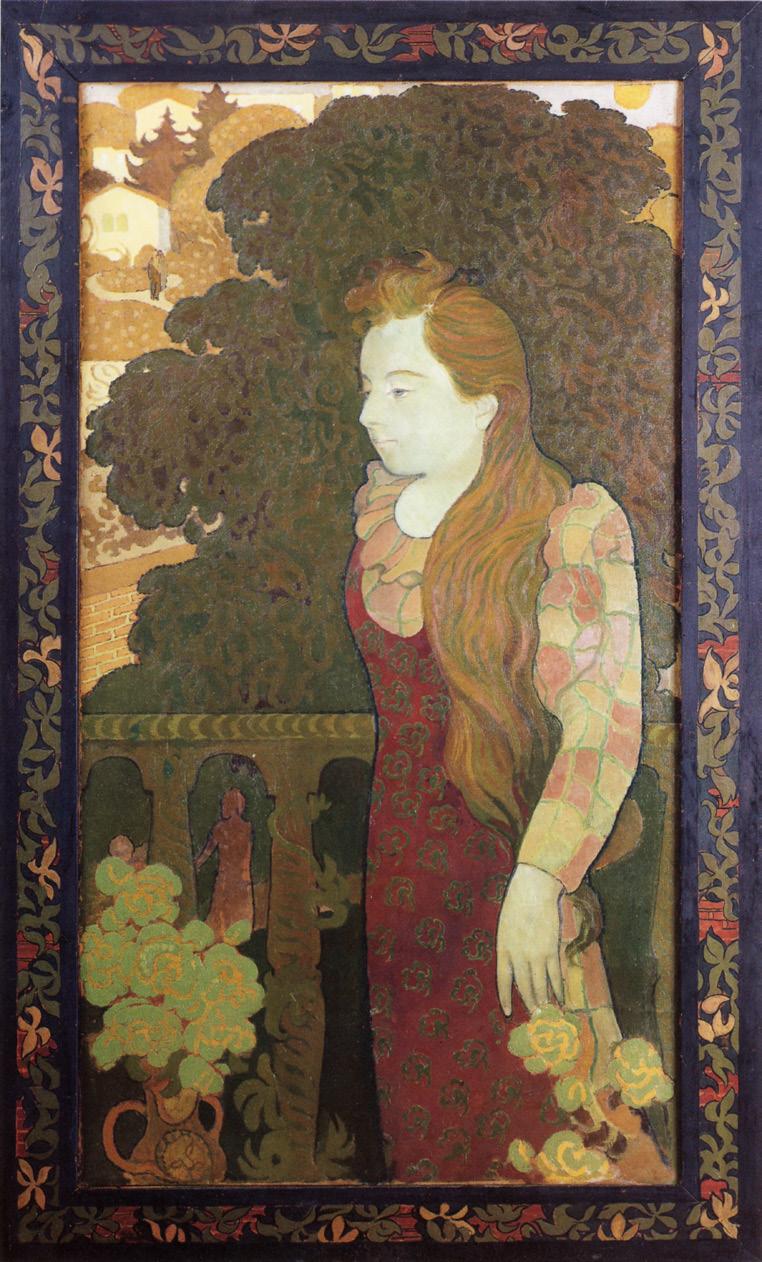

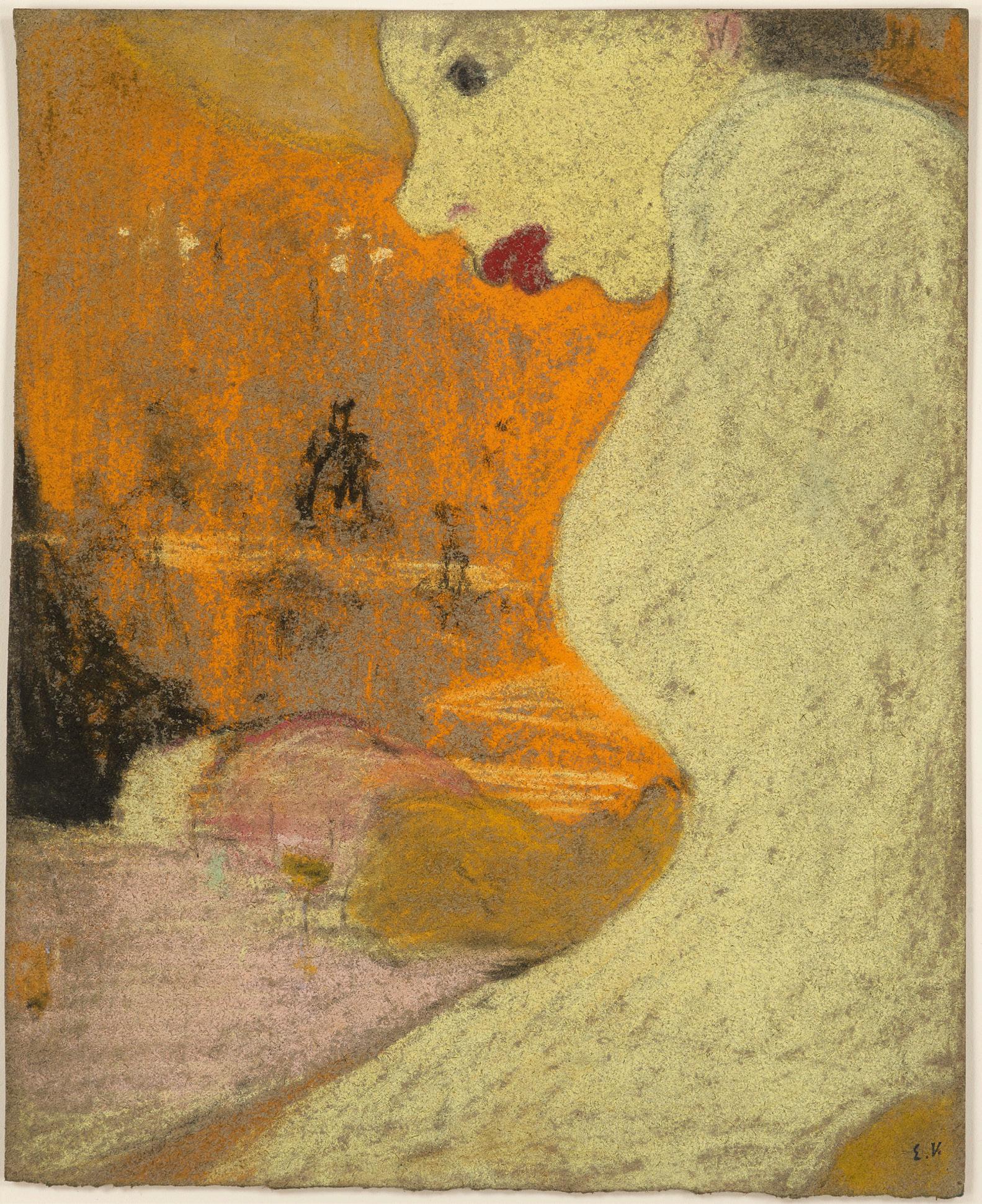

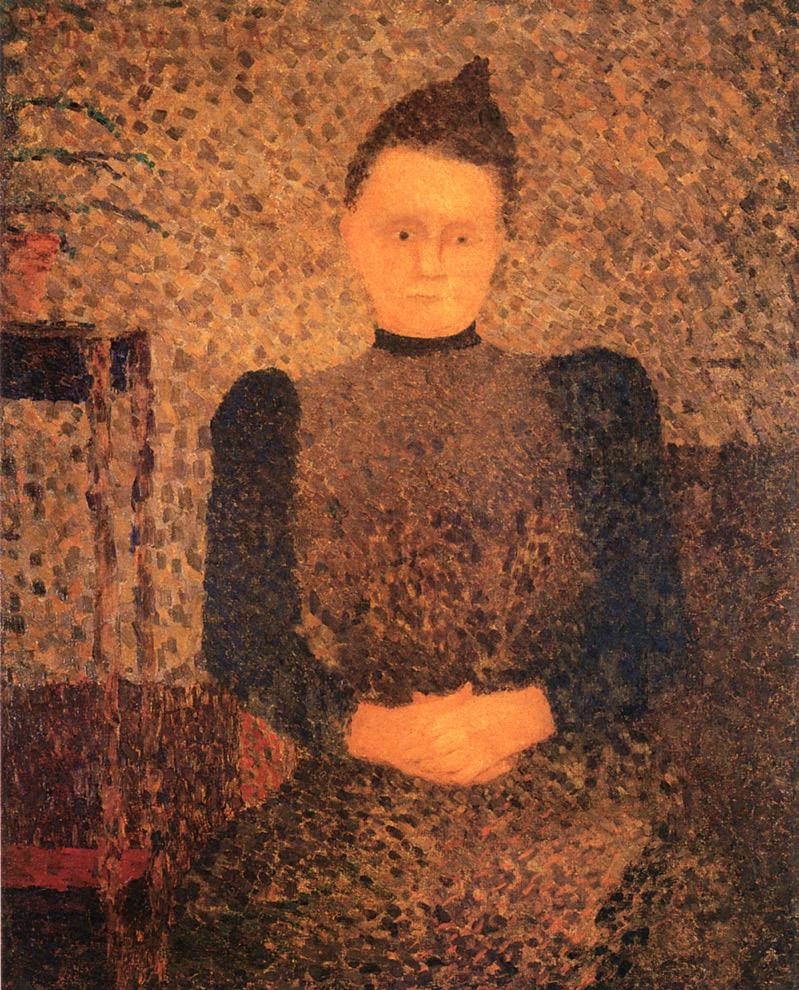

At first glance, Portrait de Marthe au tablier rouge (esquisse) (c. 1892) [p. 58] has all the characteristics of a genre scene: a young woman dressed in a checked blouse and an orange-red apron is seated before a window, through which a large tree and a few houses can be made out. As she looks at us, she lets a napkin slip gently from her hands onto her lap. We are familiar with the elements in this composition: the setting is Saint-Germain-enLaye and the hills of Fourqueux are visible in the distance. This is the town where Maurice Denis and Marthe Meurier met in 1891 and got engaged a year later. Between their engagement and their wedding on 12 June 1893, the young couple experienced hopes and doubts as the opposition of their parents to the marriage grew. During that year, Denis painted a dazzling series of portraits of his fiancée, of which this is one. Denis settled on Marthe’s slightly upright pose in an early preparatory watercolour [1]. Her head faces slightly to the left and she already has a curl of hair hanging down her forehead. The background, however, is very different: two large flat fields of colour – one light, one dark – indicate that the scene is set in an interior. Denis’ final painting [2] shows Marthe seated on a sofa as she gazes

dreamily into the distance. Does this mean that Denis successively painted his fiancée in different settings and at different times of the day? Did these different scenes really exist or were they the painter’s invention?

After Denis met Marthe in autumn 1890, he wrote constantly about his happiness in a journal he had kept since the age of 14: ‘Angels are women who hold me by the hand’. This poetic periphrasis expresses the symbolic process by which Denis would record the progressive realisation of this nascent love affair. It was through a sort of prose poem Denis called ‘Les Amours de Marthe’, which he wrote between 30 June and 29 December 1891, that the artist put his feelings into words: ‘One feels more beautiful when one loves. Attitudes are easy and chaste. Life becomes precious, discreet: sunsets have the mellowness of old paintings. But it is actually the heart that is beating too fast’.1

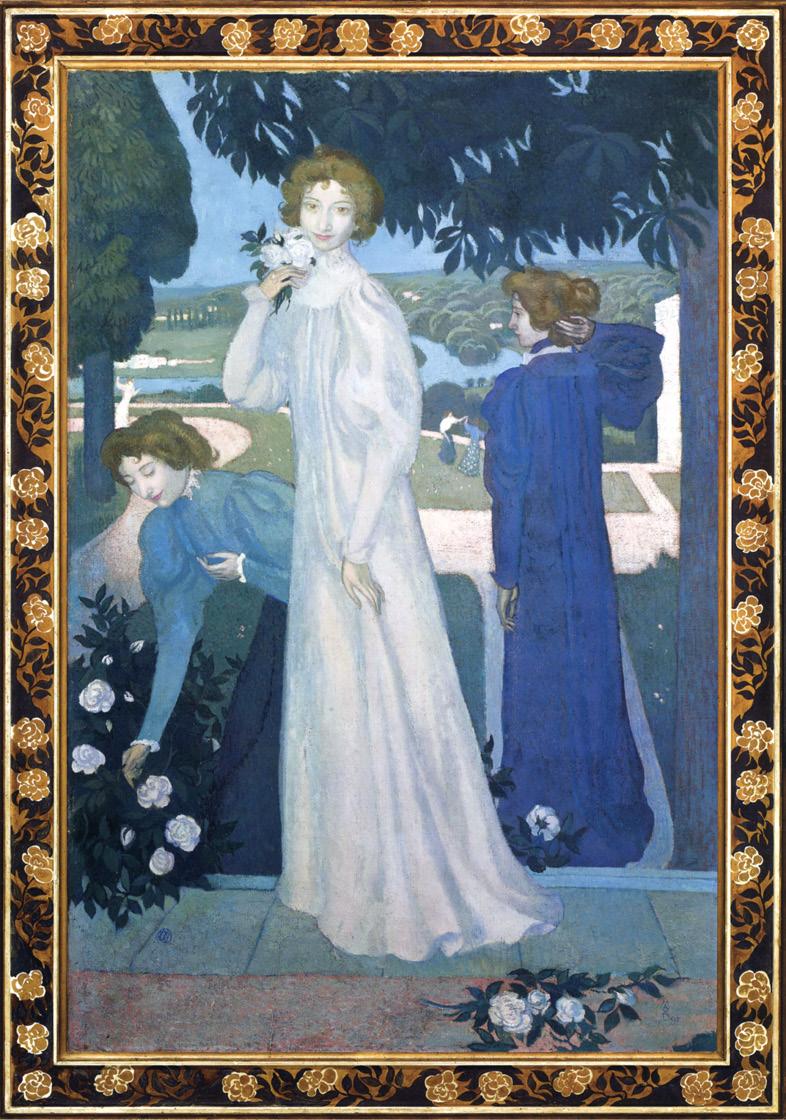

In Jeunes filles qu’on dirait des anges (1892) [3], as in certain paintings by the English

Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), we feel we are seeing a triple portrait of Marthe. Dressed in the same checked blouse, like in some of Bonnard’s contemporary portraits of his sister Andrée, Marthe seems to be an apparition. The intensity of Denis’ passion for Marthe made her, in his eyes, almost unreal. He wrote in his Journal: ‘She is more beautiful. SHE IS MORE BEAUTIFUL than all images, than all representations, than all subjective efforts! She is outside of me, it is not me who created her. The embrace of our hands last night is more valid than all metaphysics to attest the reality of things’.2

Considered from this viewpoint, the content of this painting can be seen in a new light; Denis did not simply represent Marthe as sometimes performing trivial gestures and sometimes as a Symbolist icon, his work is an expression that the marvellous is an integral part of our everyday reality. This is precisely the meaning of these lines written in his Journal:

The evening in September when I received her into my heart for the first time, the evening when she came into my life [...] She was going to do some ironing: she was fanning the stove where the irons were being heated. I can still see how she was standing. And at the same time, she was singing.

I’d never heard her deep voice. She was singing that song Entends-tu pas la nuit d’étoiles that I thought I alone loved, but that she loved too! That was how I discovered the happiness I’ve found in her ever since: her discreet love and her taste for beautiful things in the midst of humble domestic tasks.3

Denis paints a scene of everyday life in which reality is transfigured by a literary imagination in which the two lovers are steeped. In Marthe symboliste [4] or Portrait de jeune fille dans un décor de soir (both 1892) she wears her long hair in precisely the same fashion as in Portrait de Marthe au tablier rouge (esquisse), gently undulating as it descends from her left shoulder to her waist. It is not inconceivable that this is a reference to Mélisande’s golden hair into which Pelléas sinks his face. Remember that the production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, for which Denis and the Nabis created the sets in 1893, at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, was published

in 1892. In Marthe symboliste, as is the case here, a large tree spreads its foliage in the background.

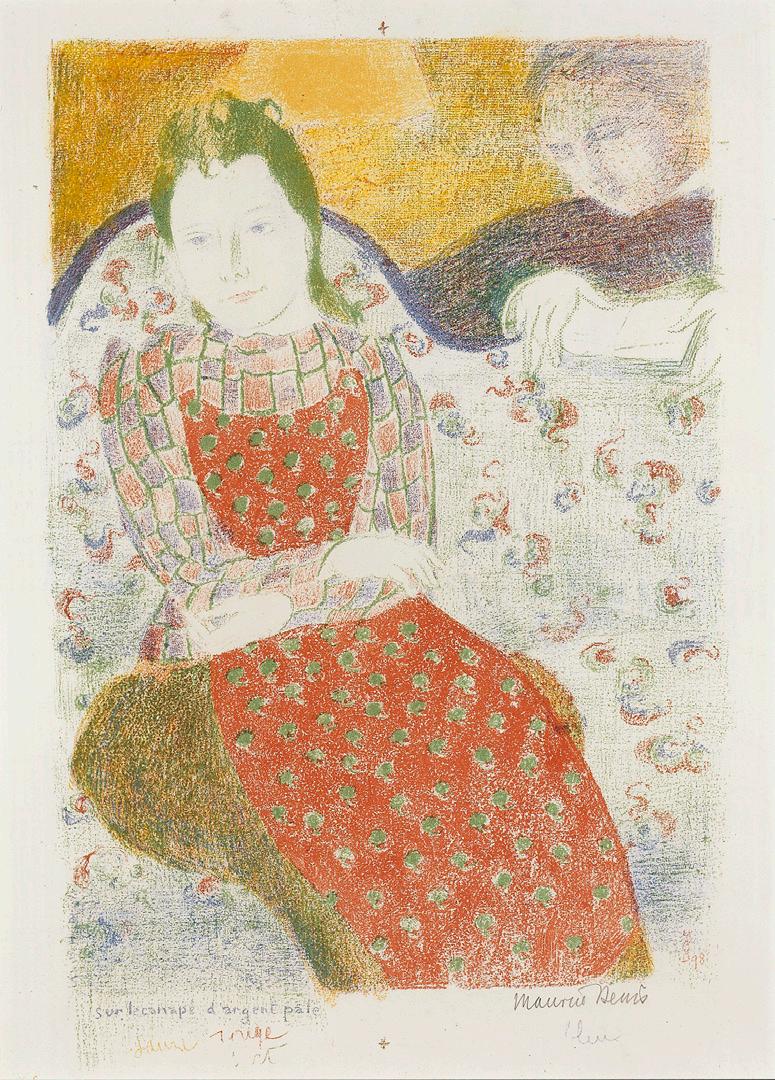

In the beautiful love affair between Denis and Marthe, music and literature were omnipresent. Denis wrote: ‘We read things from the Song of Songs, and a poem by Edgar Poe and even by Baudelaire and Mallarmé [...] She reread Princesse Maleine until two o’clock in the morning. She is pale, on edge, caressing’,4 and then added, ‘I said to her (on the pale silver sofa where we were alone together): your neck is like the Tower of David, ringed with shields’.5 The pale silver sofa, seen in Marthe au divan or Marthe au tablier rouge (1892) [2], was the setting for the pair’s first emotions as they read poetry together at night. Denis used the motif one last time in Sur un canapé d’argent pâle [5], Plate X in his series Amour, published by Ambroise Vollard in 1899.

The portraits of Marthe painted by Denis during 1892 are like the pieces of a loving jigsaw. It is difficult to have an idea of the precise

chronology of these works as Denis’ creative dynamic was never linear. In this series he simultaneously developed multiple symbolic possibilities offered by a single motif, and, enthralled, we observe as an infinite love crystallises before our eyes and, even rarer, takes material form in a series of paintings. As Denis said, ‘Dream will become reality’.6

1. Maurice Denis, ‘Les Amours de Marthe’, 30 September [1891], Journal, Tome I (1884–1904) (Paris: La Colombe, 1957), p. 85.

2. Denis, p. 86.

3. Denis, ‘Wednesday 16 November [1892]’, Journal, Tome I (1884–1904), p. 97.

4. Denis, ‘Les Amours de Marthe’, October [1891], ibid., pp. 86–87.

5. Denis, ‘Les Amours de Marthe’, Friday 23 October [1891], ibid., p. 87.

6. Denis, ‘28 November’ [1892], ibid., p. 98.

[1]. Maurice Denis, Study for ‘Marthe au divan’ or ‘Marthe au tablier orange’(1892), watercolour on paper, 31.2 × 26 cm (former Henri-Marie Petiet Collection)

[2]. Denis, Marthe au divan or Marthe au tablier orange (1892), oil on cardboard, 38 × 28 cm (private collection)

[3]. Denis, Jeunes filles qu’on dirait des anges (c. 1892) (private collection)

[4]. Denis, Marthe symboliste or Portrait de jeune fille dans un décor de soir (1892), oil on canvas, 130 × 71 cm (Niigata, Niigata Prefectural National Museum)

[5]. Denis, Sur le canapé d’argent pâle (1892–1899), plate X from the Amour series, colour lithograph on paper, 53 × 41 cm (private collection). Published by Ambroise Vollard in 1899

1894

watercolour, ink, graphite and pen on paper 13 3/4 × 29 3/4 in / 35 × 75.5 cm

signed and dated lower right ‘MAUD 94’;

Private Collection

Tajan, Paris: 19 March 1983 (lot no. 34)

Collection Sam Josefowitz

Christie’s, Paris: 2 December 2008 (lot no. 7)

Galerie Hopkins, Paris

Private Collection

‘The Nabis and the Parisian Avant-Garde’, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, New Brunswick, NJ, 4 December 1988 –14 February 1989; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 11 March – 21 May 1989, cat. no. 53, pl.12 (repro. in colour), pp. 39–40, p. 78

‘Nabis 1988–1900’, Kunsthaus, Zurich, 28 May – 15 August 1993; Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 21 Sept. 1993 –3 January 1994, cat. no. 193, p. 372 (repro. in colour)

Les Nabis, Claire Frèches-Thory and Antoine Terrasse, Flammarion, Paris, 1990, title page (repro. in colour), p. 161

Maurice Denis, Jean-Paul Bouillon, Skira, Genève, 1993, p. 65 (repro. in colour)

This painting is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity, dated 4 July 2023 and signed by Claire Denis, the artist’s granddaughter.

Indisputably one of the most accomplished watercolours of the 1890s, Au Pont du Nord un bal était donné (1894) [p. 65] demonstrates Maurice Denis’ love of the decorative arts and the way in which he gave great symbolic value to everyday objects.

Like William Morris and the English PreRaphaelites, the Nabis had the goal of renewing the decorative arts with the aim of turning our everyday surroundings into a total work of art. Every object, from a door handle to a dessert table, a carpet to wallpaper, had to be artistic. It was with this in mind that in 1891 Pierre Bonnard entered the competition at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs to design a dining room. In a more theoretical perspective, in 1892 Denis argued for an alliance between art and crafts, even between artists and the business world: ‘Where is the businessman willing to enlist the invaluable help of these decorators, to take a little of the time they devote to making many paintings?’1

Without waiting for actual commissions, Denis began to produce a series of designs: between 1891 and 1898, decorations for fans, some of which make direct reference to his relationship with Marthe Meurier; and wallpaper designs,2 including Les Colombes, Les Trains and Les Bateaux Jaunes, all conceived in 1893. Only Les Bateaux Roses (1893) was printed by L’Estampe Originale, directed by André Marty.

Between 1893 and 1899, Denis created in partnership some fifteen lampshade designs; Fête de noces sous les lanternes (1893), today in the Sant Collection, promised to the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC [1]; Erlkönig (The Alder King) (17 November 1893) based on Goethe’s poem set to music by Franz Schubert, this piece, Au Pont du Nord un bal était donné; Marthe et Noële aux brebis (1896), Marthe et Noële aux marronniers (1896); Chevaux de bois (1900); and Le Trottoir roulant (c. 1900). Some have come down to us as sketches, while others, like Au Pont du Nord un bal était donné, are

very well finished. Originally designed to be used with paraffin lamps, lampshades began to interest artists in the 1890s and 1900s as electricity was introduced more widely, as attested by the works of Antonin Daum and the artists of the Nancy School.

Making skilful use of flat tints and perspective, and the contrast between straight and sinuous lines, Denis took inspiration from Japanese graphic works to create a rhythmic image. The influence of Japonism, which was very fashionable in Paris following its widespread presentation at the Expositions Universelles (1867, 1878, 1889), is seen here in several instances; first, in the Japanese paper lanterns lighting the bridge, a motif Denis had already used in Fête de noces sous les lanternes and in Erlkönig (1893); second, in the Japanese lanterns that Whistler installed in his Peacock Room (1877) and that Henri Rivière used as a repetitive motif in La Tentation de Saint-Antoine [2, overleaf], presented at Le Chat Noir a production at Le Chat Noir in 1887; third, lanterns that graced the cabaret Le Divan Japonais, run from 1883 to 1892 by the poet Jehan Sarrazin on the Butte Montmartre; fourth, in the decorative motifs on the dancers’ dresses, which seem to have been taken directly from the plates published by Siegfried Bing in his review Japon Artistique (1888–91); and lastly, in the elegant [1]

winding lines Denis uses to depict swirling water.

Japan did not provide the only influence here, however: the two cartouches framing the boat, which bear the title of the song that gives the image its name, are explicit references to the Middle Ages, of which Denis was a great enthusiast. They suggest two lines by Paul Verlaine from the collection Sagesse (1880), for which Denis composed illustrations between 1889 and 1893. The meticulous precision with which he drew his motifs is reminiscent of the art of medieval enamelling.

Music had already been the central theme of Erlkönig, based by Denis on Schubert’s lied sung by his beloved Marthe. Denis had numerous ties with music; he was a close friend of Ernest Chausson, who bought many of his works, also of Claude Debussy, whose score of Pelléas et Mélisande he illustrated in 1894, and of Vincent d’Indy. The musical reference in Au Pont du Nord un bal était donné is not to classical music but an anonymous folk song. As often occurs with such songs, several versions exist due to regional variations and adaptations. In the original version, the story is related to the bridge in Nantes where a mother refuses to let her daughter, called Hélène, go dancing. In defiance of this injunction, Hélène’s brother, here seen wearing a top hat, takes the girl out in a boat that overturns when part of the bridge collapses:

Upon the bridge of Nantes, a dance is held / Fair Hélène longs to join the joy dispelled / ‘O dearest mother, wilt thou let me go?’ / ‘Nay, nay, my daughter, thou shalt not do so’ / She climbs her chamber, tears begin to flow / Her brother comes, in a boat gilded bright / ‘What troubles thee, dear sister, on this night?’ / ‘Alas, dear brother, I shan’t join the dance!’ / ‘Oh, fear not, sister, I shall thee advance’ / ‘Take thy white dress and thy belt all of gold’ / Thrice she did turn... the bridge no longer holds / Fair Hélène into the Loire swiftly falls / ‘Alas! dear brother, dost thou hear my calls?’ / ‘Nay, nay, dear sister, I shall save thee yet!’ / Into the waters, both their fates are set / The bells do toll, with sorrow deeply met / What makes the bells to toll so loud and clear? / Tis for Hélène and thy son held most dear / Behold the fate of children, stubborn still 3

Faithful to the text, Denis includes all the details in the song: while the mother reiterates her command with a gesture on the far right of the composition, to her left men and women in festive dress are dashed into the water. Created in the early days of his marriage, just after their 1893 honeymoon in Brittany, the subject matter is far from insignificant and should be understood not in its literal sense but in its symbolism. Remember that in the early days of his relationship with Marthe, Denis was subject to doubt: would his love for his beloved be compatible with his artistic and spiritual commitment? In this context, the fact of the couple being thrown into the river must be understood as the materialisation of the possible perils that threatened Maurice and Marthe. Traditional places of socialisation, in the 19th century dances and balls were looked on with suspicion by the religious authorities. However, the story related by this song should be understood as a metaphor for a passage, a bridge between an earlier life and a future existence. And, in fact, 1894 was the year that Denis resolved the existential questions that had beset him

and gave himself permission to be himself, so that he might offer his beloved a life of fulfilment. From this perspective, the golden boat, depicted fancifully as if it had come out a dream, becomes the symbol of this journey towards a new life full of hope.

1. Pierre Louis [Maurice Denis], ‘Pour les jeunes peintres’, Art et critique, no. 90 (20 February 1892), pp. 94–95.

2. See the catalogue of the exhibition Bonnard to Vuillard, The Intimate Poetry of Everyday Life, The Nabi Collection of Vicki and Roger Sant (Washington, D.C., The Phillips Collection, 26 October 2019 – 26 January 2020), pp. 136–37.

3. See Bernard Cousin, L’Enfant et la Chanson, une histoire de la chanson d’enfant (Paris: Éditions Messidor, 1988).

[1]. Maurice Denis, Fête de noces sous les lanternes (1893) (detail), ink, watercolour and gouache on paper, 17.2 × 71.7 cm (Roger and Vicky Sant Collection)

[2]. Henri Rivière, Scene for La Tentation de SaintAntoine, presented at Le Chat Noir, December 1887

c. 1894–96 oil on card 11 × 8 1/4 in / 28 × 21 cm

stamped lower right with the artist’s round workshop monogram ‘MAUD’

Collection Noële Maurice-Denis Boulet (the artist’s daughter); thence by descent to Jean-François Denis (the artist’s grandson)

Galerie Huguette Berès, Paris (directly from the above in 1992)

Private Collection, London (acquired from the above)

‘Paris in the Nineties’, Wildenstein Gallery, London, 12 May – 23 June 1954, no. 23

‘Paris 1900’, Musée Jenisch, Vevey, Switerland, 17 July – 26 September 1954, no. 41

‘Maurice Denis’, Musée de l’Hôtel de ville, Pont-Aven, France, 17 June – 15 September 1979, no. 21

‘Maurice Denis’, Galerie Huguette Berès, Paris, 4 June – 22 July 1992, no. 36 (repro. in cat.)

This painting is accompanied by a photocertificate of authenticity, dated 26 May 2023 and signed by Claire Denis, the artist’s granddaughter.

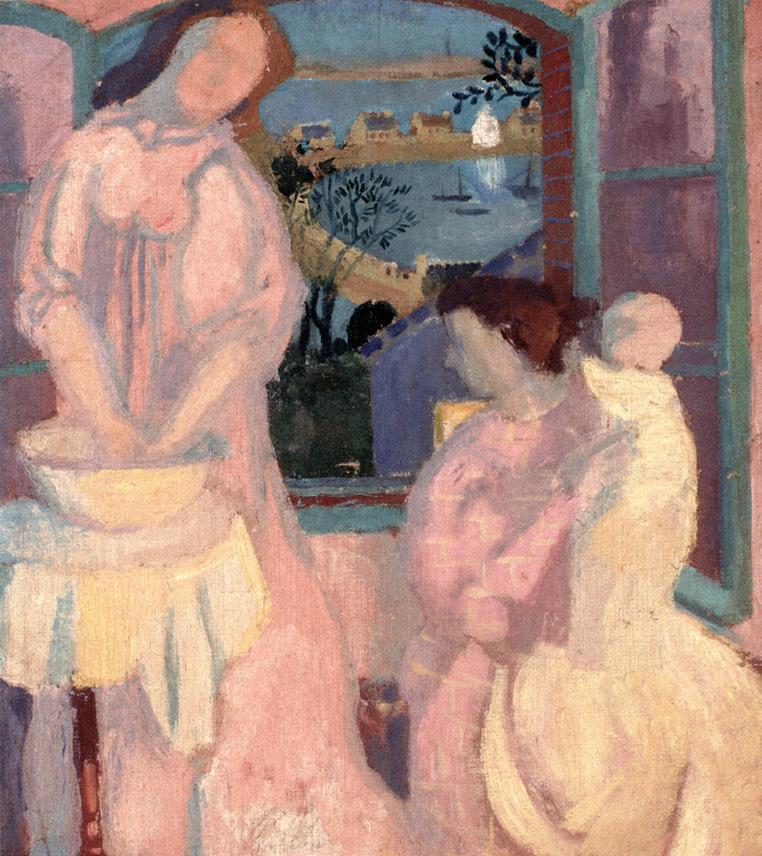

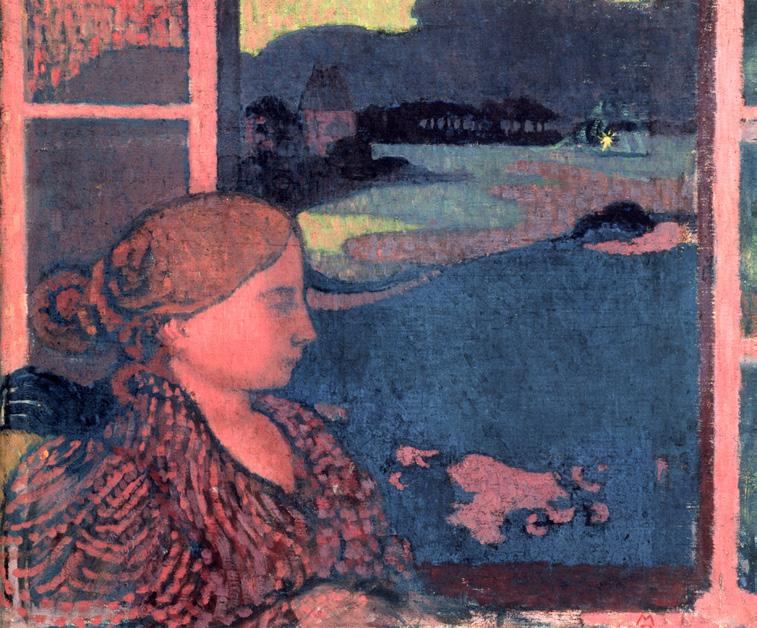

Some paintings are so poetic that the tools of art history are insufficient to convey their sublime beauty; Devant la fenêtre bleue (c. 1894–96) [p. 74] is one of them.

We are in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Maurice Denis and Marthe Meurier, who had met in 1891 and married two years later, are living in Villa Montrouge, a small apartment situated below the upper town, whose windows look out onto the hills of Fourqueux and Mareil-Marly. As this had been the setting of his childhood and his first love affairs, Denis knows every lane of the place and always paints them realistically. Thus, the white wall across the centre of Devant la fenêtre bleue (c. 1894–96) is the Priory built at the request of Madame de Montespan, for which Denis had great fondness on account of its history. As a result of the commission for a decorative cycle made to Denis by the great Russian collector Ivan Morosov, for his Moscow mansion, Denis purchased the Priory and made it his home; it is now home to a museum dedicated to the artist’s work. The landscape in the background of the composition the one seen in Le Pré aux chevaux (1893) [1]

It was in Villa Montrouge that Denis and Marthe’s first child, Jean-Paul, was born in October 1894. Marthe was often visited there by her sister Eva, a musician like herself, who in Devant la fenêtre bleue Denis shows standing in pensive mood, not unlike the one

adopted by the young woman in blue seen from behind in Portrait d’Yvonne Lerolle en trois aspects (1897) [2]. The essential elements of Denis’ affective universe are thus brought together here, and would reappear year after year in later works, like motifs in a tapestry woven over time.

A recurring motif in the history of art, the window became the cornerstone of the revolution of artistic representation in Renaissance Italy when the philosopher, painter and mathematician Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) described a painting as being a window on the world. Breaking with the vertical arrangement of planes characteristic of the Middle Ages, the artists of the Quattrocento began to construct their works using perspective. A diligent visitor to the Louvre from the time of his youth and a passionate admirer of Italian painting, Denis had a perfect understanding of this revolution in aesthetics. What is fascinating about Devant la fenêtre bleue is how it reintroduces

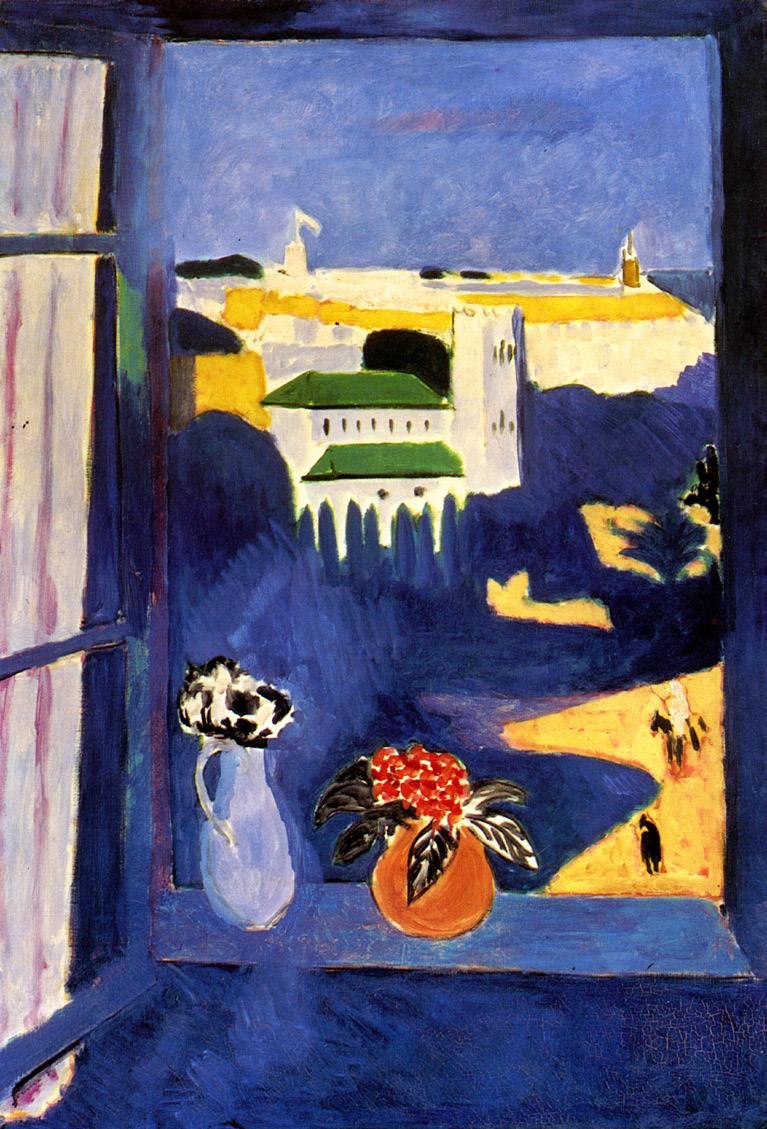

compositional stacked planes, integrating them with the formal experimentation of the Pont-Aven School: the foreground is constructed with several flat tints of blue, like a succession of flat surfaces. Eva, whose face is barely sketched in, is portrayed without volume, like a figure taken from a Japanese print and slid sideways between two flat planes. Denis would return to this idea of young women with blank faces in Figures à la fenêtre verte, Perros (c. 1897) [3]. In both cases, the space between the two casements offers the viewer visual perspective, functioning as a painting within a painting. When we consider the mastery with which Denis has transfigured reality in this work, it is easy to understand the fascination that the young Henri Matisse had for the works of the Nabis [4].

The meaning of this painting, however, cannot be divined through simple formal analysis; this young woman, in a landscape depicted in various shades of blue (a nighttime scene?), whose gesture appears to point toward somewhere other than her present circumstance, no longer fully belongs to everyday reality. To grasp the scene’s atmosphere, it is useful to consider the doubts and hopes expressed by Stéphane Mallarmé in his

poem ‘Les Fenêtres’ (Windows), published in Vers et Prose in 1893: ‘Let the glass be art, let it be mysticism / To be reborn, wearing my dream as a crown, / In a past heaven where Beauty flourished!’1 And to understand this mysterious dreamlike apparition, we also need to refer to verses by Verlaine:

The sky above the roof / Is so blue, so calm! / A tree above the roof / Sways its fronds […] Dear God, dear God, life is there, / simple and still. / That peaceful murmur there / comes from the town. / What have you done, you who are here / weeping endlessly? / Oh, what have you done, you who are here, / with the days of your youth? 2

The repetition, if not the frequent recurrence, of the motif of a young woman at a window in Denis’ later work, for example in Temps gris sur l’île, also known as Le Soir (c. 1894) [5], is not at all inadvertent. The confrontation between inside and outside, between the protective space of intimacy and that of adventure, undeniably speaks of the relationship with reality and the quest for

construction of the self. It is of no real importance that the setting in Le Soir is no longer Ile-de-France but Brittany: the poetic and symbolic framework remains the same, in scenes featuring identified but idealised characters. Baudelaire summed it up brilliantly in his poem of the same title, Les Fenêtres: ‘What does it matter what reality is outside me, provided it has helped me to live, to feel that I am and what I am?’3

1. Stéphane Mallarmé, ‘Les fenêtres’, La Revue indépendante (1887), pp. 18–20.

2. Paul Verlaine, ‘Le ciel est par-dessus le toit’, Sagesse, partie III , poème VI . Eng. trans. Muriel Kittel, Anchor Anthology of French Poetry from Nerval to Valéry (New York: Doubleday, 2009), p. 97.

3. Charles Baudelaire, ‘Les Fenêtres’, Petits poèmes en prose, 1869. Own translation.

[1]. Maurice Denis, Portrait d’Yvonne Lerolle en trois aspects (1897) (detail), oil on canvas, 170 × 110 cm (Paris, Musée d’Orsay)

[2]. Denis, Le Pré aux chevaux (1893), oil on cardboard, 25.3 × 25 cm (private collection)

[3]. Denis, Figures à la fenêtre verte, Perros (c. 1897), oil on canvas, 59 × 47 cm (Pont-Aven, Musée de Pont-Aven)

[4]. Henri Matisse, Fenêtre à Tanger (Tangier, spring 1912), oil on canvas, 115 × 80 cm (Moscow, Pushkin Museum, formerly in the collection of Ivan Morosov)

[5]. Denis, Temps gris sur l’île or Le Soir (c. 1894), oil on canvas, 47.5 × 55.5 cm (Douai, Musée de la Chartreuse)

1863–1928

Charles Filiger was introduced to drawing as a child by his father, who worked as a draughtsman at the Thann fabric company. After attending a Jesuit school, in 1880 Filiger decided to study the decorative arts and, in 1887, moved to Paris to follow the courses at the Atelier Colarossi on Rue de la Grande-Chaumière.

He visited Pont-Aven frequently between 1889 and 1892, and became friends with Paul Gauguin and Paul Sérusier while all three were staying in Le Pouldu, at the Buvette de la Plage belonging to Marie Henry (called Marie Poupée). Filiger spent the rest of his life in Brittany, sometimes visiting Paris to see his patron Antoine de la Rochefoucauld, who financed him from 1890 to 1900, the year that their relations ceased.

Although Filiger also received money from his family, from 1895 he suffered serious financial hardship. Loneliness, worsening health (he was neurasthenic) and alcoholism obliged him to continually change boarding houses. Between 1905 and 1910, he was also confined twice in hospices. Filiger survived on sales of his paintings and pottery decorations. He broke from his brother Paul in 1910, shortly before the latter’s death. In 1914, he was taken into the hotel in Trégunc run by the Le Guellec family, who looked after Filiger until his death in 1928.

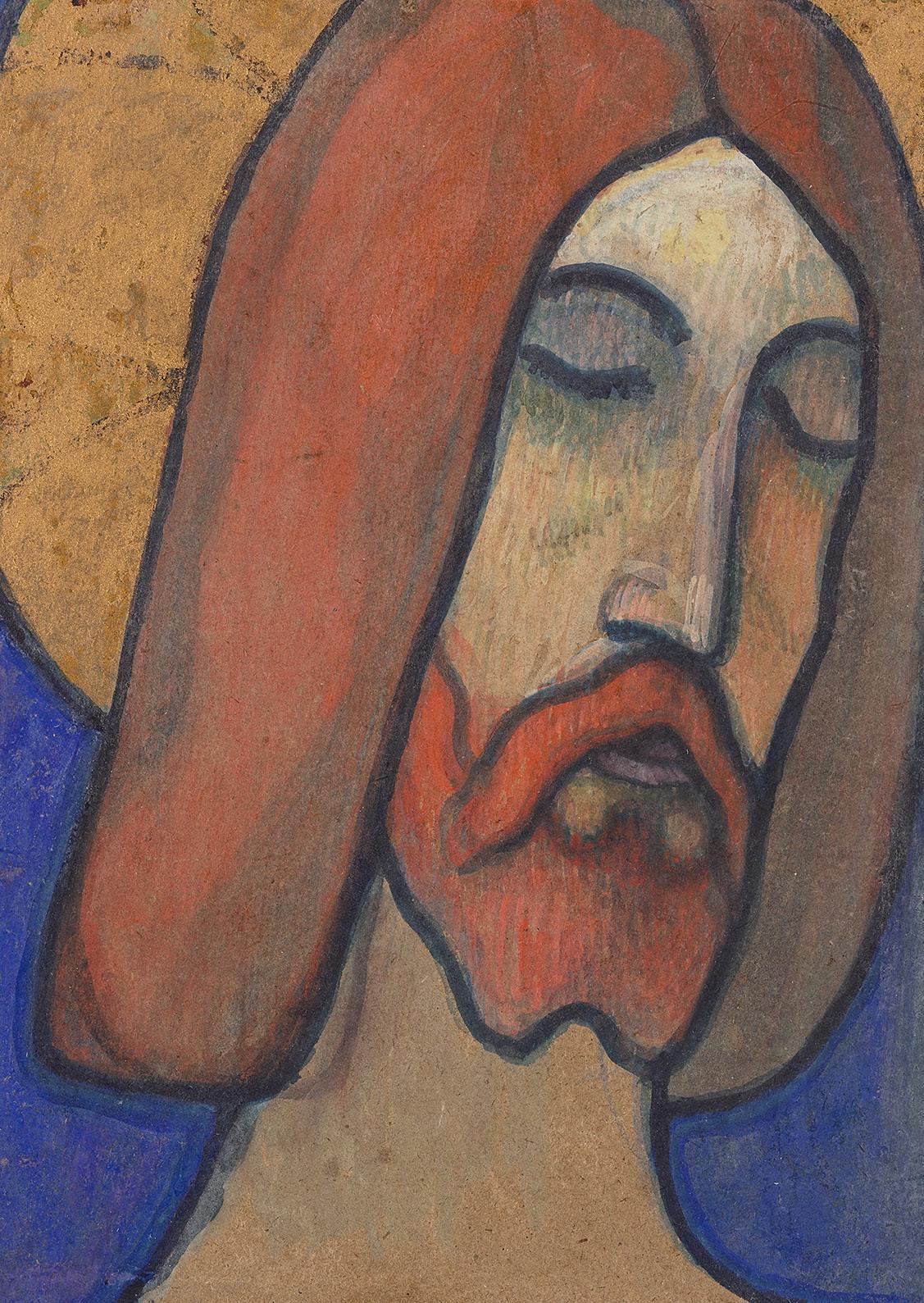

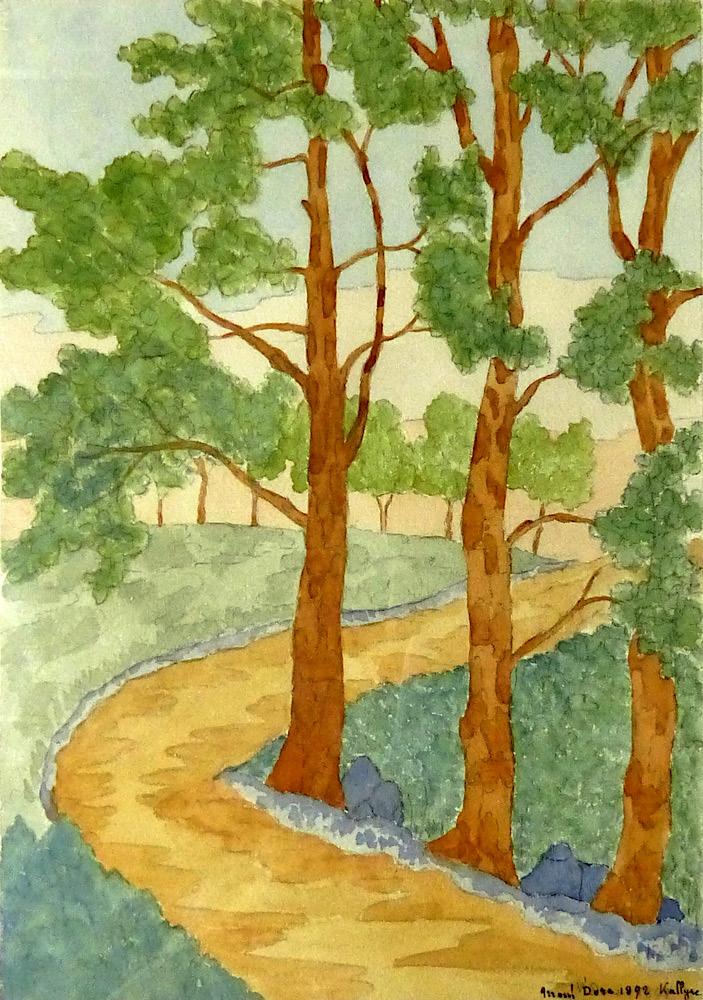

c. 1892

gouache on card 8 7/8 × 7 3/8 in / 22.4 × 18.6 cm

Comte Antoine de la Rochefoucauld, Paris (directly from the artist); thence by descent to Eugène de La Rochefoucauld (his son)

Mira Jacob

Arthur G. Altschul, New York (acquired December 1961)

Private Collection, Paris (acquired from the above in 2002)

Private Collection

‘Gauguin og hans venner’, Winkel & Magnussen, Copenhagen, 1956, no. 56

‘The Nabis and Their Circle’, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, MN , 14 November –30 December 1962, cat. p. 142

‘Neo-Impressionists and Nabis in the Collection of Arthur G. Altschul’, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 20 January – 14 March 1965, cat. no. 27, pp. 74–76 (repro. in b&w)

‘Il Sacro et il profano nell’arte dei simbolisti’, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Turin, 1 June – August 1969, cat. no. 128, p. 120 (repro. in b&w)

‘The Sacred and Profane in Symbolist Art’, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1–26 November 1969, cat. no. 107, p. 102 (repro.)

‘Filiger: Dessins, gouaches, aquarelles,’ Musée départemental Maurice Denis, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 14 November 1981 –15 February 1982; touring to Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, 5 March – 30 April 1982, cat. no. 23, p. 46 (p. 47 repro. in b&w)

‘Charles Filiger’, Musée d’Art Moderne, Strasbourg, 16 June – 2 September 1990, cat. no. 21

‘Filiger: curated by André Cariou’, Galerie Malingue, Paris, 27 March – 22 June 2019, p. 40 (repro. in colour)

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin, vol. LI , no. 4, December 1962, p. 142

Melvin Waldvogel, Art International VII /I, 1963, p. 55

Paul Gauguin et l’école de Pont-Aven, Wladyslawa Jaworska, La Bibliotheque des Arts and Éditions Ides et Calendes, Neuchâtel–Paris, 1971, p. 165 (repro.), p. 260

Filiger l’inconnu, Mira Jacob, Le BateauLavoir, Paris, 1989, no. 74

Filiger. Correspondence et sources anciennes, André Cariou, Locus Solus, Châteulin, 2019, no. 53

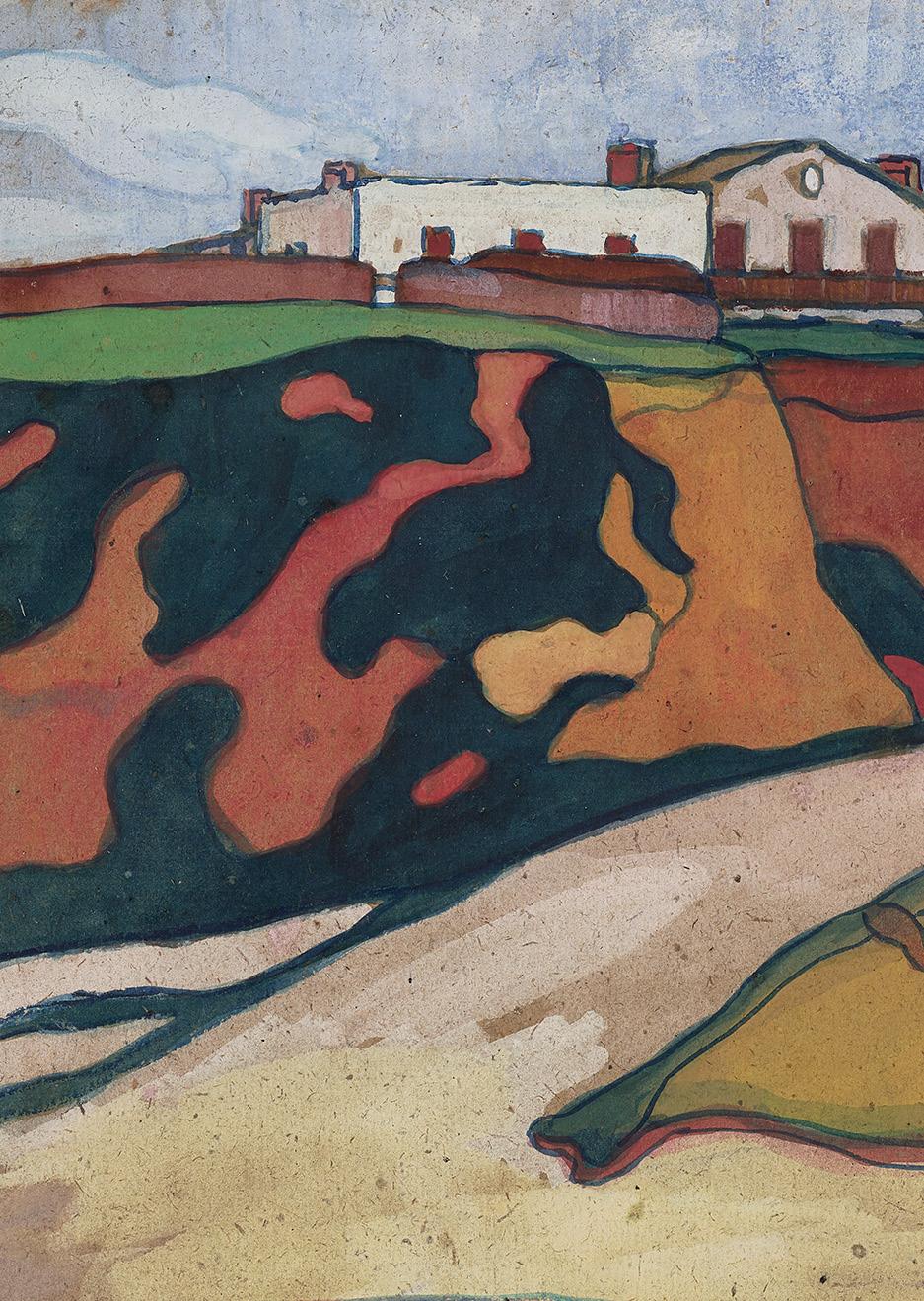

1891

gouache on card 12 1/4 × 10 in / 32.7 × 27 cm

signed upper right ‘FILIGER’