C T P A A

O E O R R

N M R Y T

THE MARK H. REECE COLLECTION OF STUDENT-ACQUIRED

C T P A A

O E O R R

N M R Y T

All

Table of Contents

Foreword

In 1963, Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, P ’81, P ’85), Wake Forest’s dean of men and College Union advisor, had a vision to establish a contemporary art collection for the College. In the true spirit of Wake Forest and its consistent mission to make our students and their learning goals our first priority, all acquisitions for this new collection would be led by students. At the time, Wake Forest lacked not only an art collection but also an art department. Even so, Dean Reece’s bold objectives were unanimously accepted by the governing board: to purchase and collect student-selected art created during each generation and to bring localized awareness to the College’s shortcomings in the area of art and — thereby, they hoped — see a department of art established.

With no money allocated that first year for the purchase of artwork, Reece cobbled together funds from other student organizations that went unspent the previous year. That June, Dean Reece, along with Dean Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, P ’93), Professor J. Allen Easley and two students, drove to New York City — the center of the contemporary art world — with the purpose of exploring the city’s art galleries. They returned from that first trip with a dozen works of art, all selected by the students.

Every four years since, an acquisition committee composed of a small group of students has traveled to New York City with university funds to purchase art by nationally and internationally recognized artists for what is now named the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art. As courageous and progressive as it was in 1963, the

students’ charge has remained consistent over six decades: to purchase artworks that reflect the times. This brilliant policy has built a collection that today is both a reflection of major trends in modern art history and an ode to the social and political concerns shaping each four-year period.

What started as an experimental concept, the “student artbuying trip” (as it is fondly known), now serves as a model for peer universities and still remains the most rigorous and robust learning and acquisition experience of its kind. This revered tradition has empowered three generations of students to amass a nationally renowned collection of contemporary art.

This catalog celebrates the 60th anniversary of the student art-buying program and the collection that honors Dean Reece and his visionary leadership. This publication would not be realized without the support from John (’81) and Libby Reece (P ’09, P ’14). Their steadfast commitment to the care and stewardship of the Reece Collection that honors their father and father-in-law paved the way for this commemorative catalog. Our gratitude goes to the following alumni, faculty and staff members for their insightful contributions to the catalog: Professors Jay Curley and Leigh Ann Hallberg; J. D. Wilson (’69, P ’01), 1969 student artbuying trip participant and tireless supporter and advocate of the Reece Collection; and former student art-buying committee members Caroline Culp (’13) and Jay Buchanan (’17), whose catalog entries expand the discourse about the Collection. We thank Madeleine Douglas (’23) for her initial

design work and editing and Jessica Burlingame, collections manager, who was a key contributor to the success of this project due to her attention to detail in amassing images, image rights and other essential information.

Our gratitude to Hayes Henderson, Shana Atkins, Kris Hendershott and Jill Carson of Wake Forest University’s Communications and External Relations team, who gave structure and beauty to the design of this book and shepherded us through this effort.

Our heartfelt appreciation goes to Cristin Tierney (’93) and J. D. Wilson, co-chairs of the 60th Anniversary Reece Collection Steering Committee, and all Steering Committee members and donors (alumni, parents and friends) who have supported the Reece Collection and student-led art acquisition program with their deep commitment to our students. A special note of gratitude to Cathy and Jeff Dishner (P ’21), whose generous gift will increase the frequency of the art-buying trip to every three years starting in 2024, allowing more students to participate in this transformative experience.

We thank the leadership of the Provost’s Office for years of support for the program, and the vice provost of the Arts & Interdisciplinary Initiatives, Professor Christina Soriano, who continuously uplifts the Reece Collection and the studentled art acquisition program as a cornerstone of Wake the Arts. We acknowledge all current and former professors in the art department, with a special note of remembrance for

Professor Robert H. Knott, whose guidance and leadership helped to maintain the integrity and rigor of this program. We recognize all the faculty and staff who taught the required Global Contemporary Art & Criticism courses, served as advisors, accompanied students on buying trips to New York, acted as art stewards and taught from the collection. We also recognize Paul Bright, director of Hanes Gallery, and his team for their collaboration and exhibition support for Reece Collection acquisitions over the years.

Good art poses questions and introduces us to ideas and concepts. The art of our time serves as a catalyst for open discussion and intellectual inquiry about the world today, underscoring the spirit of Pro Humanitate. For that, we extend our deepest gratitude to all the artists in the Reece Collection for inspiring our students, faculty and staff to glean such benefits from art in which we can also see ourselves.

Finally, we thank all the alumni who served on acquisition committees from 1963 to 2021, each of whom brought their dedication, passion and unique perspective to the process and spent hundreds of hours researching artists to contribute to the legacy of this remarkable collection.

Thanks to the generosity of Alex Acquavella (’03), I am fortunate to be the curator of the Wake Forest Art Collections at this moment, stewarding the Reece Collection into the next decade and working with students and faculty to integrate this extraordinary collection into the curricula and communities of Wake Forest University.

Jennifer Finkel, Ph.D. Acquavella Curator of CollectionsI will be forever grateful to Wake Forest art history professor Robert Knott for his enthusiasm and generosity regarding the student-led art acquisition program; the “buying trip,” as it has been colloquially known for years. When I began teaching as an adjunct professor in 1999, I had many conversations with Bob about the program and its enormous benefits to students and to the institution. We marveled at the enriching and unique experience the trip provided, and we shared our thoughts on trends in the art world, emerging philosophies and potentially interesting artists for the students to consider. When Bob, in a seemingly casual way, reached beyond the usual boundaries of hierarchy and status to recommend that I be a participant in the program alongside Professor Jay Curley, I was dumbstruck. To be invited to be a part of this innovative, groundbreaking venture was sheer joy. I am so grateful for his generosity in allowing a then-lecturer to participate in guiding students on the buying trip. Thank you, Bob! We so miss you.

Why

Should Students Buy Art for a University Collection?

Leigh Ann Hallberg (P ’12) Teaching ProfessorThe students’ sole criterion for selection of artworks for the Reece Collection is to purchase works that “reflect their time” at Wake Forest. “Their time” is a difficult, slippery concept, and I would say students’ understanding of that time evolves as they move forward through the program. There are certain topics that will appear as obvious subject matter, such as identity, war, climate change, migration and so on. Students push deeper into content and each work’s resonance beyond its initial topicality. Do the work’s formal properties support and augment the subject matter and content? Does the work continue to ask questions of the viewer? And on a more pragmatic level, how does this work relate to the existing collection in terms of media, size, the gaps it might fill and our ability to care for and display it.

The question of whether Wake Forest should even be collecting art has been discussed, especially considering the lack of a dedicated space for its presentation. I, too, have thought about the Reece Collection in this light. There is an argument that collecting art is only a means of signaling wealth and status. Obviously, for some people, it is. If you Google “art and money,” the search engine’s results are pages and pages of articles titled, for example:

• “The Three Most Expensive Contemporary Artists of the Year So Far”

• “Top Ten Most Expensive Artworks by Living Artists”

• “The World’s Ten Most Valuable Artworks”

Students need to understand all aspects of the art world, even the coarse and ignorant parts, if they are going to participate in this world. But most importantly, students need to understand that art is about much more than money. As John Berger stated in his BBC television series from 1972, “Ways of Seeing”:

“It’s as if the painting, absolutely still, soundless, becomes a corridor, connecting the moment it represents with the moment at which you are looking at it, and something travels down that corridor at a speed greater than light, throwing into question a way of measuring time itself.”

I cannot imagine trying to teach art, the making of it or its history, without the experience of looking at physical, material, present works of art. Pedagogically, students need access to unmediated examples of what they aspire to make and study. Looking at reproductions or projections of artworks does not allow for an authentic, faithful experience of the work. Seeing works in person makes an enormous difference. When students’ lives are dominated by screens, the experience of relating to a physical work of art is essential. A tiny Instagram image or a small work that has been blown up to fit a projection screen without accurate color and texture is no substitute for apprehending and learning from an actual work of art. Our Reece Collection, which has been carefully and thoughtfully selected by students, encourages discussion, asks questions, gives hope, challenges and creates joy for the entire Wake Forest community.

I have had the pleasure of participating in the Reece Collection program twice, in 2009 with Professor Jay Curley and in 2017. When I think back to 2009, what I recall most vividly are the debates and deliberations. After spending three and a half days pounding the Chelsea pavement, we returned to a rather dark conference room at our hotel to decide what to purchase. A number of works were being considered, but two expensive works were at the core of the discussions: The Sleep of Reason, a large photograph by Yinka Shonibare, and a large cyanotype by Christian Marclay. The students did not have sufficient funds to buy both. I wish I had recorded the conversation! The discourse was intelligent, respectful and INTENSE. I will never forget that discussion. At one point, I made small sketches of all the works being debated on separate cards along with their prices so that the students could create groupings of works that they might purchase within the

budget. Arguments for the Marclay, now an iconic work in the Reece Collection, prevailed. We also purchased a small Shonibare collage that has been exhibited most recently at Reynolda House Museum of American Art in the exhibition substrata. I was immensely proud of those students. The seriousness with which they addressed their task, not in terms of money but in terms of what the artworks purchased would mean to future students, was inspiring.

The program has occurred every four years, and as a rule, seniors and sometimes juniors were chosen as participants. I remember having to reluctantly tell inquiring students that the trip would occur in a year when they, first-years or sophomores, would most likely not be able to participate. It seemed unfair to not consider students who might not be as polished or advanced but who were knowledgeable and enthusiastic. So in 2017, I intentionally sought to carefully review applications of superior students beyond just juniors or seniors. The 2017 students included three seniors, one junior and two sophomores. Previous groups contained odd numbers of participants to break any ties in voting, but the group in 2017 simply coalesced at six, and I asked that all decisions be unanimous. The students agreed. With a generous gift from Wake Forest parents Cathy and Jeff Dishner (P ’21), starting in 2024, the program will occur every three years for the next 15 years, allowing for a greater number of students to experience this amazing opportunity. 2017’s deliberations were also memorable in that then-Provost, Rogan Kersh (’86), was involved. Provost Kersh had always voiced his enthusiasm for the program and invited students to fill him in on the proceedings. When deliberations did come to a unanimous conclusion, the students did not have sufficient funds for shipping the works back to Winston-Salem, and so the students just gave him a ring and asked for a bit more money. Granted! Amazing!

Participants in the student-led art acquisition program have gone on to work in the art world as curators, art educators, artists, gallery directors, gallery accountants, registrars and exhibition managers. This program allowed them to experience and participate in the art world, giving them incomparable insights. The works that they have purchased have given the Wake Forest community an invaluable resource for learning, for contemplation, for debate and for pure enjoyment.

Reflecting the Time: The Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art

John J. Curley Associate Professor of ArtWhat can the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art tell us about the historical moment in which certain objects were acquired? Certainly, students’ purchasing decisions reveal something of shifting artistic tastes since 1963, but what might they tell us about the social and political events of the time? In other words, how can these works illuminate the “history” part of “art history”? In this short essay, I will investigate these questions using the 1969 and 2021 art-buying trips as short case studies.

The late 1960s were among the most tumultuous years in American history. The protest movement against the Vietnam War was at its height, and the general disregard for authority was particularly strong on college campuses, even among the relatively conservative student body of Wake Forest. In April 1969, just after students from the 1969 buying trip returned from New York, Life magazine’s cover story covered the protests, sometimes violent, erupting on American college campuses. The sheer stylistic variety of the student acquisitions that year, as well as the content of particular works, engages with the nationwide culture of protest in 1969. (See J. D. Wilson’s essay in this volume for his personal recollections of this trip.)

The four students who traveled to New York in 1969 bought more works than any other art-buying trip group. When considered together, the 20 works represent a broad spectrum of artistic styles and practices. This becomes clear when we look at the 1969 trip’s artwork from some of the more famous artists: Paul Cadmus’ careful realism in Male Nude NM 59 from 1968, Adolph Gottlieb’s late example of Abstract Expressionism Green Ground, Blue Disc from 1966, and Roy Lichtenstein’s Hopeless, an exhibition poster from 1967 associated with Pop Art. Lesser-known artists continue this diversity of styles: Hungarian emigré Margit Beck’s lightly colored abstraction, German printmaker Paul Wunderlich’s surrealist figuration and Sidney Goodman’s deadpan depiction of a prosaic gas storage tank. Perhaps the variety and quantity of works can retrospectively reveal

a moment of crisis over the role and function of art and the lack of cultural consensus circa 1969. Put simply, the stylistic chaos within this group of 20 works can mimic the larger social and political confusion of these four college students confronting their contemporary moment.

The content of several of the works purchased in 1969 also directly reflects the social turmoil of the moment.

Uruguayan artist Antonio Frasconi’s The Involvement III (1967-1968) depicts ghostly, white American planes in a black sky dropping bombs on an already-scorched, blood-red landscape. Jasper Johns produced his more politically subtle lithograph Flags in 1967-1968, featuring the American flag motif he has engaged repeatedly throughout his career. Johns used the optical tricks of complementary colors to make his political point: When viewers stare at the upper, miscolored flag and then shift their focus to the lower gray depiction, human perception creates an afterimage that renders the flag, in the perception of the viewers, in its familiar colors of red, white and blue. Johns seems to suggest that patriotism is something that is both deeply personal, seen only in an individual’s mind’s eye, and just a mere illusion.

Students most recently purchased art for the University during the spring semester of 2021, a time during which Americans were wrestling with another deeply consequential moment in history. First, the COVID-19 pandemic changed the very nature of everyday life. In addition to the trauma of dealing with a new, highly contagious and deadly virus, students’ classes and social lives largely moved online. The art-buying trip was also radically transformed; for the first time, students did not travel to New York and instead met with galleries on Zoom to make selections. Second, the brutal murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 led to a profound racial reckoning in the country that, among other things, addressed the structural and institutional effects of white supremacy in America. (The 2021 students

marked this event directly, selecting Jorge Tacla’s May 25, 2020, a blurred rendition of a Black Lives Matter protest in the unsettling medium of pigment mixed with cold wax.) The group’s discussions transcended national politics and artistic strategies; they also critically examined Wake Forest itself, especially the lack of diversity in the Reece Collection. Works by artists of color and women only constituted a small percentage of the overall purchases since 1963. Students in 2021 offered a corrective — beginning to rectify this lack of diversity while also finding works that addressed the ways that the institution of art has long perpetuated histories of exclusion based on race, gender and sexuality.

Students purchased nine works, and none were made by a white-identifying man. This diversity of artists is unparalleled among the other trips: three artists identify as Black, four as members of the LGBTQ+ community, two as South Asian and three as Latinx. The issues presented in Zanele Muholi’s Thandiwe I, Roanoke, Virginia from 2018 can represent the students’ overall aims with their acquisitions. Muholi is a South African photographer who identifies as nonbinary, using the pronouns of they/them. Their photograph is a self-portrait taken about 100 miles from Wake Forest’s Reynolda campus — in Roanoke, Virginia — that depicts the artist with a headdress made of American currency. Not only does the money suggest the violent commodification of the body inherent to the slave trade, but the portraits on the bills themselves suggest a microhistory of American race relations until the Civil War: the so-called father of the country, George Washington, owned enslaved Africans; Alexander Hamilton was born in the eastern Caribbean, and his name is the title of the famous Broadway play that offers a revisionist account of the nation’s founding; Abraham Lincoln was the president during the Civil War who issued the Emancipation Proclamation; and Ulysses S. Grant was the Union general who defeated the Confederacy in 1865. The artist, framed by these white American men,

stares intently at the viewer while standing in a Southern landscape — confronting the picture’s Wake Forest viewers with this racial history while also offering an image of a strong, resilient Black individual who can and will overcome.

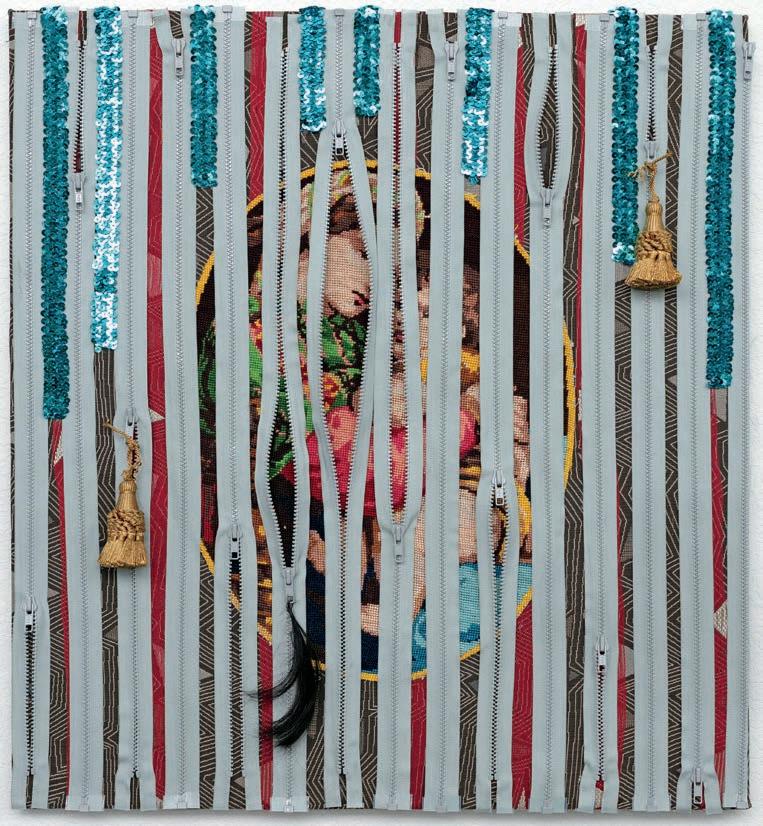

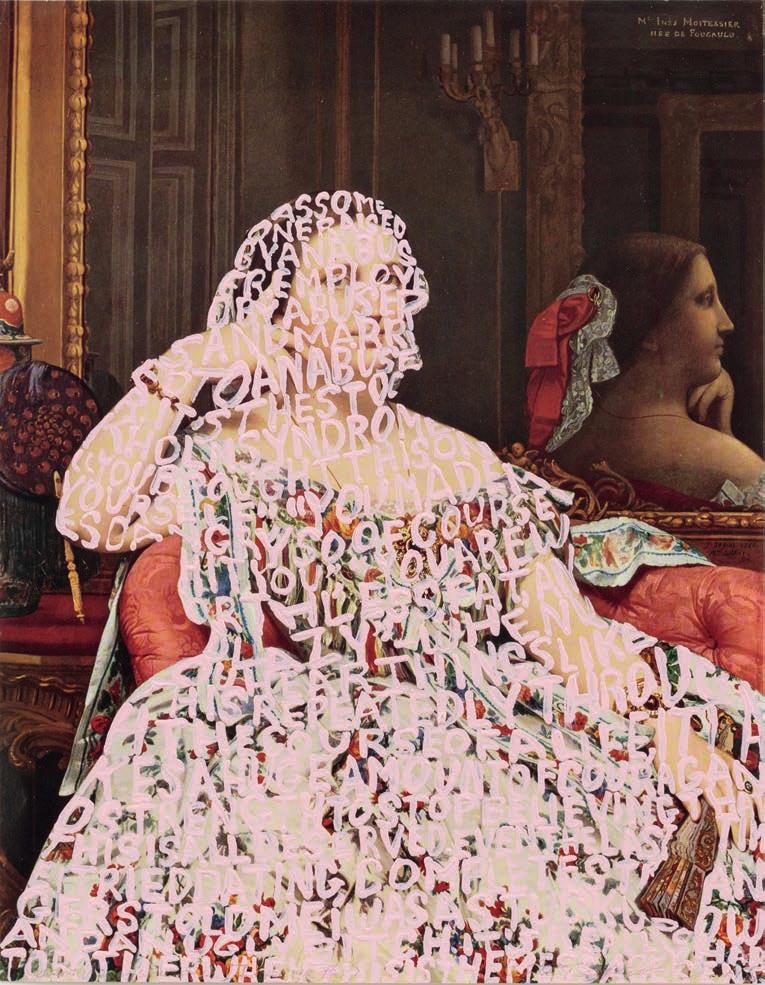

Other works also carry a significant political charge. Betty Tompkins’ Women Words (Ingres #3) (2018), offers a deeply unsettling text about misogyny covering the body of a woman in a reproduction of a work by 19th-century French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres; Salman Toor’s The Meeting (2020) riffs on Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles and subject matter to think about his identity as a queer Pakistani man in a cosmopolitan world; and Martine Gutierrez presents herself as a bold work of colorful art in a traditional museum in Queer Rage, Don’t Touch the Art (2018). This photograph suggests how stories like hers, a queer Latina with Indigenous heritage, have been ignored in most art museums. These three examples, with at least two others purchased in 2021, explicitly reference past traditional works to help viewers recognize and question art’s historical ties to the institutions of colonialism, misogyny, bigotry and white supremacy. When viewed among other works of art, they force us to reconsider our assumptions about the perceived neutrality of past works of art. They remind us of a vital fact: All art is political.

Since all art is political, we should be mindful that Reece Collection works acquired during less eventful years are as significant as any others. One of the real gifts of these works is that each trip’s selections are a snapshot of the participants’ hopes and fears told through works of contemporary art. If the only charge given to selected students is that the art they purchase reflect the times, the Reece Collection can serve as a window into how students negotiated their own experiences relative to larger social, political and artistic forces.

A Vision for the Arts. A Distinction for Wake Forest.

J. D. Wilson (’69, P ’01)Those who truly know Wake Forest know it’s a unique place not easily described. It has character and a certain spirit of confidence, often playing above its size, and it feels good just to be there, walking the friendly and friendly-looking campus. It also has had leaders of character, such as Dean Mark Reece, a man of many titles and talents — all centered on students and the student experience. He helped define what makes Wake Forest so special and devoted his life to doing so — as acknowledged by his receiving the Medallion of Merit, Wake Forest’s highest honor for service to the University.

How appropriate it is that the art collection he conceived now bears his name. Like his lifetime of focus on students, the art collection uniquely has students making buying decisions. Early radical collaboration.

So who was Mark Reece?

To me, he was my first recognized mentor, showing me that mentorship is a strong value that defines the Wake Forest experience, as he guided me through campus leadership positions, giving me confidence to do things I had never done and, ultimately, to lead. He impacted my life in countless positive ways, including its trajectory.

To some, he was our version of the iconic Norman Rockwell. They shared similar interesting faces. Sometimes Dean Reece wore a flat cap and tweed jacket with leather-patched elbows. Or smoked a pipe while zipping about campus in his small MG convertible — British racing green. And, of course, Rockwell and Reece both loved and had special connections to the world of art. And golf.

His proudest roles, though, had to be as the spouse of Shirley and father of Mark, John, Lisa and Jordan in their “Leave It to Beaver” home setting on Faculty Drive, where I was a frequent guest. They treated me like family, as Wake Forest does so well.

He was leader of the College Union, now the Student Union. Names changed, as I entered Wake Forest College and graduated from the University. As Wake Forest defines its bold vision of “Wake the Arts,” which I applaud loudly, I see proven seeds of success from the College Union days. Frankly, being involved in College Union was a way to be immersed in the future world of work in a safe campus environment; it was an entrepreneurial and leadership incubator at its core — for all who took advantage of it.

The Major Functions Committee engaged us to plan and execute big concerts of top entertainers in Wait Chapel — from soup to nuts: deciding which artists to get; participating in negotiations, budgeting, contracts, marketing and public relations, and ticket sales; setting up the stage; running the soundboard; and ensuring contractual items were in dressing rooms. We were running a business — with Mark Reece looking over our shoulders, letting us make decisions, guiding us and assisting with challenges. Our entertainers were Simon & Garfunkel, Dionne Warwick, The Lettermen, Ray Charles, Sam & Dave, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Marcel Marceau, Carlos Montoya and more.

Of course, the Arts Committee played a major role in my life, as I was tapped to be one of four students for the 1969 art-buying trip to New York City. Our guides were Dean Reece, Provost Ed Wilson, and Professors Allen Easley and Sterling Boyd.

To make the trip more affordable, I drove my car, and we stopped overnight at Harv Owen’s (’71) home in Pennsylvania. The four of us on that trip were the late Beth Coleman (’71), Leslie Hall Hallenbeck (’72), Harv and me. It was my first (and only) time driving in New York City.

Our days were tightly scheduled, a gallery here, a gallery there, then lunch, then more galleries, then dinner, and then a night in the room of our four elders to defend works on our list, deleting some and taking notes. We had the same intense schedule the next day and then a final vote. In. Out. We also had real-world lessons to learn about staying within our financial limits (about $35,000), as there was a large work by Larry Rivers, now considered by many to be the godfather or grandfather of Pop Art, we chose to give up so we could have the broad range of choices we made — the largest number in the collection. Our instinct to buy Rivers’ work was validated when I visited Williams College Museum of Art in 2009 and the first focal point was an almost identical work by him. It hit me: They had a Rivers and a dedicated art museum.

One of the most memorable highlights of the trip was a visit to the Park Avenue penthouse of Barbara Millhouse, creator of Reynolda House Museum of American Art. She and Winston-Salem native, the late Bob Myers, hosted us for a reception, followed by dinner at an Irish pub. It was the first time I’ve taken an elevator up directly into a home.

High above a transom was a slide projector displaying 10-second views of the latest contemporary art. She used that innovation to show us the importance of contemporary art and how it gives meaning and life to the walls of our homes and special places.

Another memory in her living room happened as I looked down on the coffee table at a picture of R. J. and Katharine Reynolds — reminders that I was in a very special home — when out from the bedroom came a little boy in his pajamas to tell mommy goodnight. That was my introduction to Reynolds Lassiter, her only child, who said goodnight to us as well. Years later, as a young adult, he lived in WinstonSalem, and we served on boards and strategized together on initiatives to benefit Winston-Salem and Wake Forest.

My true introduction to art happened my first days on campus, in 1964, as I viewed the exhibit of works purchased by students that spring. It’s beyond my telling to convey the significance that moment has had on my life. It opened doors for me at Wake Forest and then doors in Winston-Salem, especially at the iconic University of North Carolina School of the Arts, where I received an honorary degree. I was also introduced to Philip Hanes, who became my community mentor, and to Nick Bragg (’58), my arts and historical behind-the-scenes whisperer. I now have a home full of art my wife, Janie, and I have casually “collected.” Creativity and arts have continued as a life theme: Our daughter, Mary Craig Tennille (’01), who chose Wake Forest and a major of studio art, married Andy (’00), a photographer-artist centered on musicians (they met in English class at Wake Forest), and they nurture our arts-loving grandchildren, Olivia and Cy, who treasure visits to Reynolda House and Gardens and the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. A prize possession in our personal collection is the program of that 1964 exhibit that opened my eyes to the world of art. In fact, it was Sept. 15, 1964, as noted by me in pencil on the back, which my father taught me to do for experiences I never wanted to forget. The cover is Picasso’s La Femme au Chapeau, from the first purchase year.

These are but a few examples of the effect the Wake Forest experience can have on every student of every major at a unique, world- and life-impacting university. Today, through arts interconnectivity, Mark Reece continues to lead, mentor and inspire us to honor our motto of Pro Humanitate in bold support of Wake the Arts.

1960 s 1980 s 2000 s 2020 s

1970 s 1990 s 2010 s

ACQUISITIONS 1960-1969

Pablo Picasso Spanish (1881-1973)

Portrait de Femme a la Fraise et au Chapeau, 1962

Linocut

25" x 17"

1963 Acquisition

Perhaps the most influential artist of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso is best known for pioneering Cubism in the visual arts. This experimental new mode of picturing the world fractured the twodimensional picture plane, disrupting once-familiar linear relationships by abstracting, flattening and layering forms. In Portrait de Femme a la Fraise et au Chapeau (Portrait of a Woman with Strawberry and Hat), Picasso represents an unnamed woman from many angles at once. While her hair and nose are depicted in profile, her hat is shown from above and the rest of her face from a slight frontal angle. These conflicting viewpoints and the loose, sketchy quality of the engraving suggest the figure of the woman is perpetually coming into being, shifting and changing before our very eyes. Combined with Picasso’s calculated color palette — with dull browns making up the jagged lines of the composition’s framing device and bright blue and yellow geometric shapes layered over her cheeks — it is her face that draws the viewer’s attention. While the sitter’s identity is unknown, the model bears a close resemblance to Jacqueline Roque (1927-1986), who became Picasso’s second wife when the artist was 79 years old, the year before this print was completed. Because the subject vacillates between a type and an identified person, the twisting spirals at the heart of her pupils become still more enigmatic and unreadable.

Milton Avery American (1885-1965)

Morning News, 1960

Oil wash on paper

23" x 35"

1965 Acquisition

Many modern artists take an interest in everyday materials and situations. Avery said of his practice that he sought “to construct a picture in which shapes, spaces, colors, form a set of unique relationships, independent of any subject matter.” Avery continues, “At the same time I try to capture and translate the excitement and emotion aroused in me by the impact with the original idea.” Avery brings this dual project to bear in Morning News, exploring it with his signature play of solidcolor bands. A blond figure with pale gray skin and white clothing sits on a coral couch. The figure holds an open newspaper that lends the work its title; the novel color combinations further nuance the “news” of the title, as does Avery’s choice to cast the image in the soft hues of morning light. An uneven horizon line bisects the background of the painting, emerging where an upper field of pink meets a lower field of black. Avery’s work subtly influenced American abstraction, never fully breaking with figurative representation but neither allowing rigid conventions of depth and perspective to distract him from his real focus: the relationships between colors.

Leonard Baskin

American (1922-2000)

Lucas Van Leyden, 1963

Etching

16 ¼" x 21 5/8"

1966 Acquisition

Hans Erni

Swiss (1909-2015)

Le Couple Endormi, 1965

Lithograph

22" x 30"

1969 Acquisition

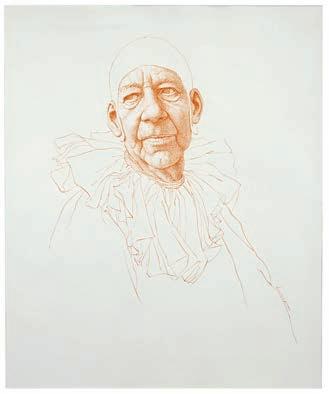

Robert Vickrey

American (1926-2011)

Head of a Clown, 1960

Sanguine ink on paper

24" x 20"

1965 Acquisition

American (1930-2020)

Untitled, 1963

Acrylic emulsion paint on cardboard 18" x 18"

1963 Acquisition

A leader in the Op (Optical) Art movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, Richard Anuszkiewicz constructs optical illusions in his abstract polymer paintings. In this untitled 1963 work, Anuszkiewicz arranges lines at regular angles, generating squares in several planes of negative space in the painting. The lines are white and yellow, arranged before a red-orange background. Anuszkiewicz refined the “color-line mixer” technique in his illusory paintings, manipulating the viewer’s perceptions through the use of color and shape so that the center of the piece appears to emit light. Speaking to the quasihypnotic effect of his compositions, Anuszkiewicz said, “I’m interested in making something romantic out of a very, very mechanistic geometry.” Viewers can evaluate the success of Anuszkiewicz’s romantic project for themselves, but art history bears out his claims to a mechanistic geometry of colors: The artist and color theorist Josef Albers mentored Anuszkiewicz. The mathematical precision of Anuszkiewicz’s Untitled provokes the viewer’s optical perceptions with scientific insights, but his play with color and his invocation of the viewer’s body give concerns of the subjective equal force in the painting.

Ruth Clarke

American (1909-1981)

Big Mountain, 1963

Oil on canvas

43 ¾" x 48 ¼"

1964 Acquisition

Paul Jenkins

American (1923-2012)

Phenomena September Morn, 1964

Acrylic on canvas

20" x 36"

1965 Acquisition

Paul Wunderlich

German (1927-2010)

Joanna in a Chair, 1968

Lithograph

25 ½" x 19 ¾"

1969 Acquisition

Sidney Goodman

American (1936-2013)

White Gas Tank, 1968

Charcoal on paper

26" x 40"

1969 Acquisition

Antonio Frasconi

American (1919-2013)

The Involvement III, 1967

Woodcut and mixed media

36" x 24"

1969 Acquisition

Green Ground, Blue Disc, 1966

Screenprint 24" x 18"

1969 Acquisition

Adolph Gottlieb helped pioneer Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s with his paintings, prints and sculptures. The artist’s minimalistic visual language took inspiration from the aesthetics of Surrealism and reformulated symbols recalling ancient myth and indigenous imagery. By the late 1950s, Gottlieb had developed his signature Burst series: flat, elemental fields of color containing a floating sphere hovering above a gestural mass. Green Ground, Blue Disc comes from this series, which ultimately centered experiments in color and form via a radically simplified image pattern. Vibrant and energetic, the palette of emerald green, sky blue and golden yellow evokes the colors of a lush summertime landscape. Looking to the environmental movement, which was newly emergent during this time, scholars have interpreted Gottlieb’s earthly imagery — with its unstable and vibrating forms — in accord with the new awareness of Earth’s fragility.

Ben Shahn

American (1898-1969)

Flowering Brushes, 1963

Lithograph

39 ¾" x 26 ½"

1969 Acquisition

Ben Shahn

American (1898-1969)

Wheat Field, 1958

Screenprint

27" x 40 1/8"

1969 Acquisition

Ben Shahn was born in presentday Lithuania in 1898 to an Orthodox Jewish family. As a child, he witnessed anti-Semitism and political persecution, experiences that became dominating influences in his work. In 1906, he immigrated with his family to New York, where he lived for the rest of his life. A successful painter and printmaker, his work focused primarily on social and political issues, often protesting against social injustice and honoring ordinary people in their suffering.

Shahn’s 1958 lithograph Wheat Field remembers his time as a photographer for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WPA-funded Farm Security Administration. During this period, he immersed himself in the austere realities of Depressionera farming. His photographs from this assignment advanced the agency’s moral mission to educate the American populace in rural economic and social reform. Looking back on this time, Wheat Field depicts a flattened row of ripe wheat. The elongated verticals of the stalks rise from the bottom of the composition in straight lines before crossing a third of the way up. The negative space around these entangled stalks creates a series of elongated diamond shapes, 27 of which Shahn hand-colored in bright earth tones. A poetic metaphor for the communities that are grown from hundreds of striving individuals, Wheat Field is an offering to the stained-glass beauty of the American farm.

Shahn included a later version of Wheat Field in an artist’s book he made a decade later, an illustrated version of the Book of Ecclesiastes. There, the stylized and flattened wheat accompanies this verse: “For everything there is a season, a time for every activity under heaven. A time to be born and a time to die. A time to plant and a time to harvest.” Illustrating this book from the Old Testament was a passion project for Shahn, allowing him to reflect on his Jewish ancestry following the persecutions of World War II.

American (1898-1969)

For the Sake of a Single Verse (folio), 1968

Lithograph 22 ¾" x 17 ¾" each

1969 Acquisition

These lithographs are part of Shahn’s For the Sake of a Single Verse, which includes 24 folio illustrations the artist made to accompany Rainer Maria Rilke’s only novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910). The Austrian poet’s semi-autobiographical novel tells the story of a college student from an aristocratic but destitute Danish family living in Paris in the early 1900s. Deploying an experimental format of plotless diary entries, Notebooks explores Paris’ gritty undercurrents of poverty and sorrow. The novel made a profound impression on Shahn, who first read it as a young man in the 1920s. And while Rilke’s expressionistic prose stayed with Shahn all his life, the artist did not create illustrations for the book until 1968 — a year before his death. Shahn published his illustrated version of Rilke’s novel in a limited print run of 750 copies. His frontispiece, an abstracted view of a twisting, contorted series of Parisian skyscrapers, foreshadows the urban scene and labyrinthine prose that follows. Other illustrations include a field of blooming flowers, the graphic outline of a hand holding a pen, a tiger and a dove.

Nathan Cabot Hale

American (1925-2021)

Fire of Spring, 1969

Welded nickel and silver sculpture

27" x 11" x 9"

1969 Acquisition

Milton Resnick

American (1917-2004)

Untitled, 1960

Oil on paper

25 ¾" x 20 ¼"

1963 Acquisition

Joe Lasker

American (1919-2015)

Yucatan Holiday, 1962

Oil on canvas

47" x 38"

1969 Acquisition

J.W. Edwards

American (b. 20th century)

Dream World, c. 1963

Oil on canvas

18" x 24"

1963 Acquisition

Robert Burkert

American (1930-2019)

The Screen Comedians portfolio, 1966-1967

Serigraph

A. Harry Langdon

20 ½" x 33 ½"

B. Buster’s World 18 ½" x 30"

C. Chaplin 18" x 33 ¼"

D. Fatty Arbuckle 21" x 31"

E. The Interior (with Stan and Ollie) 21 ½" x 31"

F. Harold Lloyd

21" x 30 ½"

23"

1969 Acquisition

American (1915-1991)

Blue and Green, 1969

Handwoven wool

116" x 96"

1969 Acquisition

Harold Altman

American (1924-2003)

Profile, 1969

Lithograph

22 ¼" x 30"

1969 Acquisition

Charles Cajori

American (1921-2013)

Small Figure, 1962

Oil on canvas

20 ¼" x 18 ¼"

1963 Acquisition

George McNeil

American (1908-1995)

Longing, 1962-1963

Oil on plywood

20" x 26"

1963 Acquisition

Paul Cadmus

American (1904-1999)

Male Nude NM 59, 1969

Crayon on hand-toned paper 22 ½" x 21"

1969 Acquisition

History celebrates Paul Cadmus for egg tempera paintings, but he also produced scores of finished crayon drawings like Male Nude NM 59. Cadmus articulates the figure’s facial features with realistic fidelity. His hair is more abstract. The nude’s closed eyes and mild smile convey peace and pleasure in equal measure. Cadmus exaggerates the musculature of the model, contorting his subject’s form and treating his skin in white-gray. Cadmus was a gay man, and his textured sex life emerges as source material for some biographical and art historical analysis of the artist. Male Nude NM 59 indeed hearkens the Renaissance vision of masculine beauty conjured by Michelangelo’s Dying Slave, which has been read through the lens of the artist’s sexuality, though Cadmus preferred the drawings of Signorelli and Mantegna (Michelangelo’s contemporaries). Cadmus also contrasts the deep detail of his figure drawing with an unrealistic sense of place in Male Nude NM 59, blurring the lines between real and unreal in the magical realist style he explored in his practice.

John Waddill

American (1927-2013)

Untitled, 1963 Polymer on paper 23 ½" x 22 ¼"

1963 Acquisition

Darell Koons

American (1924-2016)

Sunday Morning, 1963 Polymer and tempera on panel 17" x 35"

1965 Acquisition

Pablo Picasso

Spanish (1881-1973)

L’Ecuyere (The Horsewoman), 1960

Lithograph

21" x 27"

1963 Acquisition

Robert Broderson

American (1920-1992)

Child with Flower, 1963

Lithograph 24" x 18"

1963 Acquisition

Jasper Johns

American (b. 1930)

Flags, 1967-1968

Lithograph

35" x 26"

1969 Acquisition

Two years after his discharge from the U.S. Army, in 1954, Jasper Johns had a dream of the nation’s flag. The dream inspired over 40 of Johns’ works over subsequent decades, including this 1967-1968 lithograph. In the print, Johns positions two U.S. flags atop a field of rough gray. The flag in the upper half of the image bears green and black stripes, with black stars filling a bank of orange in the upperleft corner. The bottom border of the print truncates the lower flag, omitting two of the 13 stripes. On the one hand, Flags aligns Johns’ contemporaries, the Abstract Expressionists, the tactile surface of the print suggesting a handmade and bespoke quality that implies Johns’ physical contact with the image. On the other hand, Johns cedes his authority over the interpretation of this work to the ready recognizability of the flag and smoothly replicates the picture through the lithographic process. Johns said, “Using this [flag] design took care of a great deal for me because I didn’t have to design it. I went on to similar things like the targets, things the mind already knows. That gave me room to work on other levels.” Flags contains at least one deliberate perceptual trick: Staring at the white circle in the center of the green, orange and black flag produces an afterimage of red, white and blue over the grayed one. Other editions of Flags appear in the collections of MoMA and the Walker Arts Center.

Claude Howell

American (1915-1997)

Two Market Women, 1962

Oil on canvas

50" x 36"

1966 Acquisition

Isabel Bishop

American (1902-1988)

Study for Drinking Fountain, 1964

Oil on Masonite

15" x 12"

1965 Acquisition

Like several artists whose work appears in the Reece Collection, the painter Isabel Bishop practices social realism and is best recognized for portraits and urban landscape paintings that capture everyday public moments. Bishop composes Study for Drinking Fountain as a system of scratchy lines of blue and yellow-brown oil paint, exposing canvas beneath each brushstroke. A faintly defined figure appears in the center of Bishop’s study, bending over at the waist to drink from a water fountain. Bishop produced paintings and drawings of figures at public drinking fountains as early as 1947. Perhaps more than other iterations, however, the 1964 Study for Drinking Fountain reminds viewers that political phenomena seep into scenes of everyday life. Bishop’s central figure has brown skin and dark hair, and 1964 was a landmark year in the history of American civil rights. Specific attributes of the figure fade into Bishop’s color scheme, leaving their race and gender somewhat ambiguous, but the painting nevertheless encapsulates the problematic discourse surrounding the spatial rights of Black Americans in the 1960s. Raising the racial politics of public works, Study for Drinking Fountain necessitates reflection on the civic contours of Bishop’s practice.

Francis Speight

American (1896-1989)

Holy Family Church, 1942

Oil on canvas

24" x 30"

1964 Acquisition

John Hartell

American (1902-1995)

Vignette, 1962

Oil on canvas

30" x 32"

1963 Acquisition

Joseph Heil

American (1916-1974)

Autumn, 1961

Collage

6" x 7"

1963 Acquisition

William Lidh

American (1925-1999)

Garden of the Psyche, 1963

Woodcut

60" x 26"

1964 Acquisition

Margit Beck

Hungarian American (1918-1997)

Winter Slopes, 1965

Acrylic on canvas

50" x 60"

1969 Acquisition

Reginald Marsh

American (1898-1954)

Bowery Group, 1950

Chinese ink on paper

31" x 22"

1970 Acquisition

Reginald Marsh’s claims that “well-bred people are no fun to paint” and “wealthy people pay to disguise themselves” appear widely in the historical literature surrounding the artist. Marsh’s work often investigates the uneasy proximity of whimsy and darkness in public culture, especially in densely populated New York. Often positioned in the genealogies of political caricaturists like the British Hogarth and the French Daumier, Marsh’s work balances the humorous, insidious and salacious facets of an urban working-class existence in equal parts. Marsh made the double-sided inkbrush drawing Bowery Group late in his career. Marsh composes the image of organized lines that celebrate the smooth diffusion of ink on paper. Spectral architecture sets the stage: a working-class urban street. A woman strolls in the foreground. A man, possibly drunk, sits against the frame of a building, looking in the woman’s direction. Other men, silhouetted in the background, join him in leering at her. A seemingly straightforward scene, Bowery Group recapitulates the ancient moral conflict of innocence and vice on urban streets, interlacing it with the mid-century complexities of gender.

Garo Antreasian American (1922-2018)

From the Silver Suite, 1968

Lithograph

21 3/8" x 19 7/16"

1969 Acquisition

Robert Gwathmey

American (1903-1988)

Untitled, 1969

Poster

26" x 18"

1969 Acquisition

Roy Lichtenstein

American (1923-1997)

Kunsthalle, Bern Exhibition Poster – Hopeless, 1967

Printed 1967 by Albin Uldry, Bern

Serigraph

50" x 36"

1969 Acquisition

Anne Kesler Shields

American (1932-2012)

Red and Blue, 1964

Oil on canvas

52" x 40"

1964 Acquisition

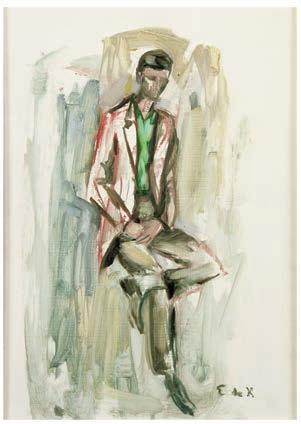

Elaine de Kooning American (1918-1989)

Portrait of Eddie #2, 1961 Oil on Masonite

13" x 9"

1963 Acquisition

A noted Abstract Expressionist, Elaine de Kooning favors a gestural application of paint, composing her 1961 Portrait of Eddie #2 of overlapping color bands. A male figure, Eddie, sits on an unpictured stool before a background of reaching bands of blue and light brown. He wears a reddish jacket, a green shirt, and brown pants and shoes. Hands folded in his lap, he properly crosses his left leg over his right. De Kooning made several paintings of her proteges Eddie Johnson and Robert Corless in the early 1960s. Histories of de Kooning’s career often omit the voices of Johnson and Corless, but these trainees supported some of de Kooning’s most significant sittings; Johnson once photographed de Kooning as she painted a portrait of John F. Kennedy. De Kooning brings geometric precision to her subject’s face, but runny trails of paint anonymize her student’s features, destabilizing the notion that recognizable likeness must power portraiture. De Kooning renders the Eddie of this portrait recognizable only through her title and perhaps the quirks of her student’s physicality. De Kooning said, “Always when I look at anyone’s art, I get flashes of the person. … To me all art is self-portraits.” In its distinctive relaying of de Kooning’s style and its relative effacement of the subject’s distinguishing features, this painting seems to challenge its own title: Is this a portrait of Eddie or Elaine?

Birgit “Gitte” Krøncke

Danish (b. 1935)

Manhattan, 1963

Oil on canvas

26" x 32"

1963 Acquisition

Grace Cranford Freund

American (1922-2013)

Intruders, c. 1965

Polymer on canvas

48 1/4" x 42"

1965 Acquisition

Stanley William Hayter

British (1901-1988)

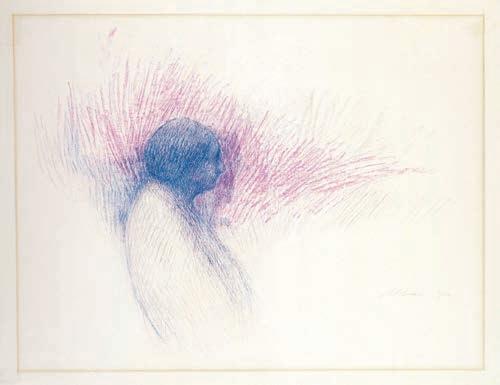

Unstable Woman, 1947

Etching

20" x 26"

1963 Acquisition

“My approach to art,” Stanley Hayter said, “is fundamentally experimental.” The British printmaker’s revolutionary reinvention of traditional gravure techniques triggered a renaissance of the process in the 20th century. Previously, artists had employed gravure as a means of reproduction; Hayter transformed the long-established technique with inventiveness and originality. Dozens of artists, including Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, came to Hayter’s famous Atelier 17 print workshop to learn from him. Unstable Woman reflects Hayter’s interest in color prints in the later decades of his career. The relationship between the female nude — the subject of the work — and the linear, spiraling background produces the “instability” of the woman, who appears to move counterclockwise. Although Hayter abstracts her body, it maintains its figurative specificity. Hayter also uses jarring shades of cobalt blue, bright fuchsia and banana yellow to create rhythm with repetitions of line and shape. Reflective of mid-20th-century Jet Age aesthetics, Unstable Woman embodies the experimental and edgy ideals of an era.

1960 s 1980 s 2000 s 2020 s

1970 s 1990 s 2010 s

ACQUISITIONS 1970-1979

Alex Katz

American (b. 1927)

Vincent with Open Mouth, 1970

Oil on canvas

96" x 72"

1973 Acquisition

Alex Katz is one of the most widely exhibited artists of his generation. Often associated with the Pop Art movement, his large-scale portraits were influenced by the graphic close-ups found in television, film and advertising that were exploding into American visual culture during the 1950s and ’60s. In Katz’s portrait Vincent with Open Mouth, the artist depicts his 10-year-old son in the stylized, flattened planes of color that mark his mature work. In a 2009 interview, the artist recalled his dependence on photography to plan such compositions, saying, “Photographs had the two things I was interested in: one, they were flat, and the other, they had nostalgia. I was trying to make something new, and flatness seemed the way to go.” The boy’s bulbous head takes up the majority of the frame. And his face, with its enigmatic expression, is so immediate it seems almost to push out from the surface of the canvas. Is his mouth open in wonder? Or are those eyes glazed with boredom? As with many of Katz’s best pictures, the painter creates a tension between the intimate and the remote, the overwhelming and the absurd. An enormous and all-consuming canvas (8 feet tall and 6 feet wide), it foregrounds what Katz called the colossal and epic “visual dominance” of the human figure in all its mundane expressions and quotidian environs.

Red Grooms

American (b. 1937)

Picasso Goes to Heaven,

1973-1976

Etching/Pochoir

28 7/8" x 30"

1977 Acquisition

Best known for his assemblages and painted installations, Red Grooms’ Picasso Goes to Heaven is crowded with big personalities and costumed characters from Picasso’s imagined afterlife. In a work begun shortly after the artist’s death in 1973, Picasso is depicted front and center with a gigantic golden halo, a hairy chest and strappy sandals. Seated on a swing held up by cherubs, Picasso glides through a melange of clowns, monkeys, nude women, trumpet players and French bureaucrats. Bumping up against the right edge of the frame, a red-faced Paul Cézanne holds a painter’s palette while he draws a single red apple on the white canvas before him. To the left of Cézanne’s easel, Gertrude Stein wears a severe Victorian gown and holds a platter of apples. Her mannish features and tiny angel wings complete the satirical tableau. A zany, cartoonish scene teeming with chaotic life, Grooms’ caricature of the 20th-century artist is just plain fun. As Grooms said, “Humor is like boxing. You set ’em up. Then, whammo!”

9" x 9" each

1977 Acquisition

Since the 1950s, Robert Mangold has explored line and color on supports ranging in shape, size and dimension. A committed Minimalist, his practice responded in a coolly strategic way to Abstract Expressionism, which dominated the American art scene throughout the mid-20th century. Working within a consistent geometric vocabulary, his spare and subtle works — from paintings and prints to constructions and glassworks — employ monochromatic abstraction as a means of communication. Five Aquatints establishes underlying order and pattern by building relationships between purely abstract geometries. Subtle changes take place as the earth-toned squares brighten over the course of the print sequence. The contrasting light and dark, straight and arching lines set up complex spatial connections that affect the way we perceive the implied dimensionality in each square. Derived from the principles of geometric science, Five Aquatints challenges the illusionistic limits of the two-dimensional print medium.

Fairfield Porter

American (1907-1975)

Under the Elms, 1971

Lithograph

32 ¼" x 24 ½"

1977 Acquisition

Fairfield Porter, a post-war representational painter, struggled for recognition during the Abstract Expressionist heyday of the mid-20th century. His portraits, landscapes and still lifes reflect traditionally realistic subject types rendered in unmodeled and soft-edged forms. Under the Elms is a lithograph after Porter’s oil on canvas original of the same year, now in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Scholars have identified the figure as Porter’s daughter, Katherine, and the house in the background as the artist’s Southampton studio. The rippling patterns of dappled sunlight on the lawn and in the shapes of the trees are reminiscent of plein air paintings by Impressionists, who were obsessed with capturing the changing light conditions found in nature. Porter’s practice was similarly based in the direct observation of his world and in his delight of everyday beauty. But unlike his 19th-century precedents, Porter’s works embrace flatness and abstracted shapes as intrinsic to the representational medium.

Bob Timberlake

American (b. 1937)

Near Boone, no date

Offset print

12" x 16 ¾"

1977 Acquisition

Robert Rauschenberg

American (1925-2008)

Visitation II, 1965

Lithograph

30" x 22"

1977 Acquisition

Robert Rauschenberg embraces rough edges across sculpture, painting and printmaking. Rough-hewn black strokes dominate the surface of Visitation II. Triangles, rectangles and a target emerge in saturated black.

Rauschenberg identified the inspiration for the Visitation prints as his experience walking in the city, in which “all you saw was a general no-colour in which the tone stood out.”

Rauschenberg includes a photorealistic image of a kitchen right of center, positioning a scene of domesticity within his tonal impression of urban movement. His title references the Christian scene in which Mary, pregnant with Jesus, meets Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. A reticent contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists and an out queer man, Rauschenberg appropriates the trappings of mainstream culture — from consumerism to religiosity to the experiments of his fellow artists — dragging them with love through a rigorous reexamination.

Visitation II replicates the general forms of Visitation I (1965), a similar but nonidentical print produced on gridded graph paper.

Rauschenberg favored “multiples” and seriality, which problematize artistic originality. A quintessential Rauschenbergian print, other editions of Visitation II appear in the collections of The Met, MoMA, Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Ron Davis

American (b. 1937)

Diamond in a Box, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

114 ½" x 133 ¾"

1977 Acquisition

Ron Kleemann

American (1937-2014)

The Four Horsemen and the Soho Saint, 1976

Screenprint

37 ½" x 41"

1977 Acquisition

Alfred Leslie

American (1927-2023)

Richard Bellamy, 1974

Lithograph

40" x 30"

1977 Acquisition

Warm Drypoint Robe, 1976 Drypoint

42" x 29 ¾"

1977 Acquisition

Jim Dine’s sprawling multimedia practice spans painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, photography, poetry and performance. Across four decades and many different types of media, Dine developed the specific form of the bathrobe as a repeated motif. This everyday object, transformed into a noble subject by the artist, functions as an imaginative self-portrait of Dine himself. The Warm Drypoint Robe print in the Reece Collection uses an extraordinary variety of textures and marks to produce an expressive image evoking a wellused and cozy robe. Loose scratches across the surface of the fabric lend the work the unfinished, casual quality of a handmade object, bringing our attention to its facture. With the arms of the robe hitched up in an attitude of attention, the wrapped cloth takes on an anthropomorphic pose full of character, as if it has a life of its own. Printmaking is a central part of Dine’s practice, and he is recognized as an extraordinary draftsman. Over his long career, he made more than 1,000 prints, including etchings, lithographs and woodcuts.

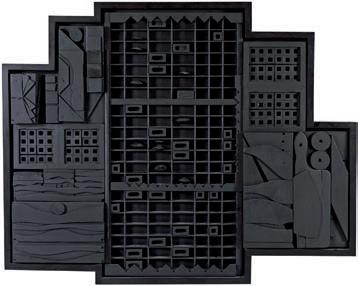

Louise Nevelson

American (1899-1988)

Night Zag III, 1973

Wood assemblage

34 ½" x 42 ½" x 4"

1973 Acquisition

Night Zag III typifies Louise Nevelson’s monumental, monochromatic wall-hanging sculptures, which the artist called “zags.” The zag sculptures exemplify Nevelson’s contributions to the mid20th-century Junk Art phenomenon. She built Night Zag III by collecting dozens of found pieces of discarded wood and organizing them into tidy but irregular grids before painting the entire composition in matte black. Despite its asymmetry, Night Zag III affords the viewer a sense of order and cohesion, systematizing rectilinear chambers, saw-toothed and curving strips, and recognizable objects like a cutting board in a bounded polygonal form. Nevelson produced some of her zags in other colors but readily admitted black was her favorite. The artist challenged the common Western association of black with fear and death, explaining, “When I fell in love with black, it contained all color. It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance.” Just as each piece of found wood has a story of its own but finds its place in Nevelson’s unification, so, too, does every perceptible color find welcome in Nevelson’s capacious understanding of black. In their complex arrangement of geometric shapes, the zags reference Cubist collages, musical compositions, Maya stelae, and the urban architecture and dynamism of New York City.

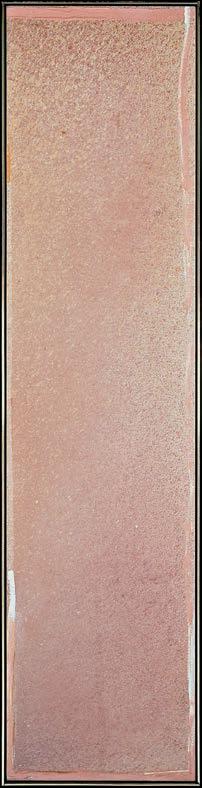

Jules Olitski

American (1922-2007)

First Years, 1970

Acrylic on canvas

94" x 23"

1973 Acquisition

Russian-born American artist Jules Olitski was at the forefront of Color Field painting, an abstractionist movement of the 1960s and ’70s made popular by Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis. His large-scale abstract paintings feature misty fields of solid color with little depth and no perspective. Working on uncut rolls of canvas with buckets of paint, spray guns, sponges and squeegees, he used spray and impasto techniques to create richly textured color surfaces. First Years is a color field framed at the edges of the canvas by brushstrokes in white and salmon pink. These marks communicate the edge of the painting and define its surface. Olitski built up successive layers of acrylic paint on the canvas, gradually changing the balance of hue and value in a fragile pinkish color reminiscent of Tiffany glass. A pale reddish spray covers some areas, adding further dimension by alluding to the subtle play of light. Together these elements create a virtually boundless, eye‐filling terrain — a dematerialized field of pure color.

American (1925-1981)

Christ Head Tondo, c. 1970

Drawing

23 ½" x 18"

1970 Acquisition

Ray Prohaska

American (1901-1981)

Floats and Markers, 1964

Oil on canvas

50" x 40"

1971 Acquisition

American (1928-2011)

Untitled, 1963

Acrylic on paper

14" x 17"

1973 Acquisition

Helen Frankenthaler was an Abstract Expressionist painter. This untitled acrylic painting on paper typifies the mode of painting, which Frankenthaler began exploring in the early 1950s and for which she would become best recognized. Her work was a direct inspiration for Color Field painting which utilizes the application of paint to large areas of canvas at a time, often engaging the canvas at odd angles to exploit gravity and the viscous materiality of paint. Frankenthaler applied a narrow field of blue and a wide field of red atop the mild base, seeking to satisfy her conviction that “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image.” While Frankenthaler enjoyed acclaim and relative success as a mid-century female artist, her male contemporaries received more market and critical attention at the height of Abstract Expressionism. Surging historical interest in recuperating Frankenthaler from misogynistic canon formation in recent decades marks the prescience of this early accession to the Reece Collection.

William T. Wiley

American (1937-2021)

Near the Red Pit, 1975

Drawing

36" x 37"

1977 Acquisition

Jack Beal

American (1931-2013)

Oysters, Wine, and Lemons, 1974

Lithograph

20 1/8" x 33"

Study For Oysters, Wine, and Lemons, 1974

Pastel on paper

19 5/8" x 25 ½"

1977 Acquisition

Ellsworth Kelly

American (1923-2015)

Colored Paper Images XVI (Blue Yellow Red), 1976

Colored and pressed paper pulp

32 ¼" x 21 ¼"

Edition 4 of 24

1977 Acquisition

Ellsworth Kelly relishes in tidy spectra of monochromatic stripes in his paintings and prints alike. Colored Paper Images XVI (Blue Yellow Red) adheres to this rule. Kelly stacks horizontal bands of blue atop yellow atop red. Kelly uses colored pulp rather than smooth industrial paper, centering the square of pigment on rough-edged paper that holds visual weight. Kelly’s work straddles the striated celebrations of color put forth by Abstract Expressionists and the neat geometries of American Minimalism. He asserted, “My forms are geometric, but they don’t interact in a geometric sense. They’re just forms that exist everywhere, even if you don’t see them.” Kelly studied at the Pratt Institute before enlisting in the mountain ski troops and the camouflage unit for World War II, which shaped his relationship with color. After the war, he continued his education at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Perhaps he encountered the specific orientation of blue over yellow over red — the oldest configuration of the national flag of Romania — during his military service and European education, though the homology could be coincidental.

Philip Pearlstein

American (1924-2022)

Nude on Striped Hammock, 1974

Etching and aquatint

23 ½" x 26"

1977 Acquisition

Philip Pearlstein was one of the preeminent American figure painters of the 20th century. He is best known for his unidealized nudes, which usually consist of one or two figures set against a stark background with only a piece of furniture and a patterned rug or blanket as supporting props. Like many of his works, Nude on Striped Hammock is notable for its use of assertive cropping — an influence, perhaps, from his early work as a layout artist at Life magazine. The print depicts a woman suspended in a hammock in the artist’s studio, one foot on the floor. From this high vantage point, we can see a section of baseboard at the composition’s upper left. A web of shadow pools on the floor below, cast by three separate light sources. Pearlstein’s overall approach to composing his almost clinically realistic nudes was not to eroticize or sexualize their bodies but, instead, to treat the figure as, he said, “the main form of my compositional structures.” He continued, “I see the arms and legs and torsos primarily as directional movements, their contoured areas as the major shapes on my page.” This depersonalization of the human body allows the life of his works to come from the abstract two-dimensional patterns created by shapes within the picture plane.

1960 s 1980 s 2000 s 2020 s

1970 s 1990 s 2010 s

ACQUISITIONS 1980-1989

Robert Colescott

American (1925-2009)

Famous Last Words: The Death of a Poet, 1988

Acrylic on cotton duck

84" x 72"

1989 Acquisition

Robert Colescott’s figurative paintings confront stereotypes while celebrating Black history. His garishly colorful Famous Last Words: The Death of a Poet centers the last moments of the Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of the first influential Black poets in American literature. The poet lies in the foreground of the composition, tucked beneath a green and red quilt. With a cigarette between his fingers, the dying Dunbar speaks the memories of his life into a microphone. These are the stories given flesh in the surrounding painting, where Dunbar himself is rendered at least three more times. Each time, he’s shown with a cigarette clenched between his teeth: in bed with a lover, in heartfelt conversation with a blond woman and in a mortal struggle with a gun-toting man. People of many colors populate Colescott’s painting, some with mottled skin tones, suggesting one race shifting into another. In a frenetic composition packed with interlocking forms, their couplings and struggles evoke a mixture of emotions, from pain to desire, love to hate. Of his paintings, Colescott asserted, “I talk about the sociology of race and sex,” and he claimed, “You can’t talk about race without talking about sex in America.” His garish and gritty recollection of a poet’s life — punctuated by sex and violence — provocatively engaged racial stereotypes still prominent in 1980s America. Three years after its installation in Benson University Center, the painting was vandalized: The body of the blond-haired lover in bed with the poet was defaced with black felt-tip pen. The artist traveled to Wake Forest to restore the painting.

Richard Diebenkorn

American (1922-1993)

Blue Club, 1981

Aquatint, spit bite, soft ground etching

37 ½" x 31"

1989 Acquisition

The artist Richard Diebenkorn is best known for a group of large-scale, luminous canvases that brought abstraction to the West Coast. Called the Ocean Park paintings, the soft-hued series took inspiration from the special luminosity of the California landscape Diebenkorn called home. Blue Club comes from the later decades of the artist’s career, when he played with combinations of abstraction and figuration. He began to draw playing-card imagery in the mid-1970s, focusing in particular on clubs and spades. Of his lifelong fascination with the iconic imagery found in playing cards, Diebenkorn said, “I had always used these signs in my work almost from my beginnings.” As a child, he invented family emblems from heraldic signs — like spades — and painted them onto homemade shields.

While his early abstract paintings incorporated clubs and spades peripherally, this new series dealt with them, he said, “directly — as theme and variation.” For Diebenkorn, such symbols had “a much greater emotional charge than I realized.”

Along with his strong sense of compositional balance, Blue Club reveals a fine sense of gestural line and sensitivity to color, lending this simple image the weight of deeper meaning.

Jody Pinto

American (b. 1942)

Henri: Renaissance Clamming, 1983 Crayon, watercolor, gouache on paper 96" x 60"

1985 Acquisition

Jody Pinto’s creative projects primarily focus on the integration of sitespecific artworks into architecture and landscape. Deriving from her practice as a painter, Henri: Renaissance Clamming is part of her Henri series, a group of works inspired by Pinto’s neighbor and childhood hero, Henri LaMothe. An Olympic swimmer, jokester and unqualified daredevil, Henri once built a 40-foot platform over a shallow pool so he could perform the death-defying feat of a four-story belly flop. In this particular work on paper, Henri’s dangling feet are visible, descending from the rough yellow clump of fireworks suspended in the sky. In the red-washed water below, two back-turned figures look on in silhouette. Inspired by the mystical imagery of Giotto and fresco paintings of the Italian Renaissance, Pinto has said that she imagined Henri to be her own personal saint. These references suggest we read the yellow mass of fireworks as evocative of an angel or crucifix. Fantastical, enigmatic and highly personal, Henri: Renaissance Clamming is an elemental ode to the magical people who populate our daily lives with drama and mystery.

Keith Haring

American (1958-1990)

Untitled, 1982

Dayglo paint and ink on paper

38 ¼" x 48"

1985 Acquisition

Keith Haring began as a graffiti artist in New York City in the 1980s, and the city informs much of his work. He approached the streets as a laboratory for his dayglo and ink creations, and Haring’s work often relies on line images of stick figures. For the dichromatic Untitled, Haring represents a breakdancer in his recognizable style, inking the details of the image onto a solid yellow background. The sole figure in the painting performs a backbend, with curving lines above and below the figure suggesting motion of the body. Haring marks the ground by a horizon line and offers dots for texture. He dates the work “1982” in the top-left corner and adds a cross-hatched circle in the top right, a symbol that is part of the artist’s personal pictorial vocabulary. This dayglo work on paper was prominently featured in Haring’s infamous 1982 exhibition at the prominent Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo, where the artist transformed the gallery into a club-like environment, covering every inch of every wall, from floor to ceiling, with paintings, drawings, wallpaper and graffiti. Like most of the figures in Haring’s oeuvre, the central figure of Untitled eludes identification as any specific individual. Such images of the dancing body could reference the dancers on the street or in the nightclub, as both spaces influenced Haring and other gay creatives in 1980s New York. The playful spirit central to so many of Haring’s paintings often belies life-and-death political stakes; the artist made big, loud artworks opposing Apartheid, drug abuse and anti-LGBTQ+ ideologies and advocating safe sex practices in response to the HIV/ AIDS epidemic. While this painting does not engage such macro-political forces in any direct way, the untitled 1982 work foregrounds joy and movement — indeed life itself — in Haring’s urban surrounds and queer communities.

Allan Erdmann

American (1931-2012)

Ives, 1979

Electronic sculpture

39 3/8" x 3 ½"

1981 Acquisition

Ed Paschke

American (1939-2004)

Rouge Clair, 1984

Mixed media

40" x 60"

1985 Acquisition

James Surls

American (b. 1943)

A Certain Great Angel, 1980

Carved and burned wood sculpture

138" x 84" x 54"

1981 Acquisition

Joseph Raffael

American (1933-2021)

Pink Lily with Dragonfly, 1981

Lithograph

41" x 29 ½"

1981 Acquisition

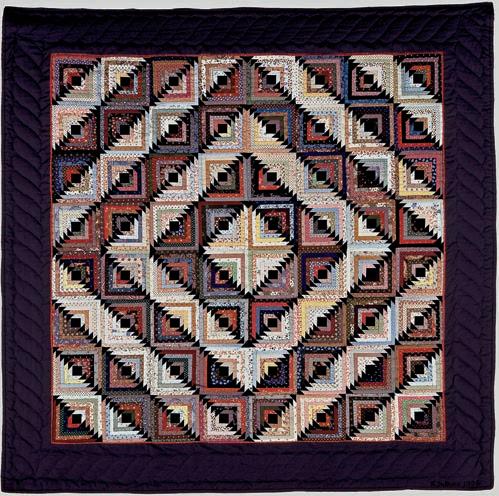

Kathlyn Sullivan

American (b. 1943)

Compulsive Log Cabin, 1986

Machine pieced, hand-quilted

48" x 48"

1987 Acquisition

John Monti

American (b. 1957)

Stand In, 1988

Charcoal on paper

62" x 27"

1989 Acquisition

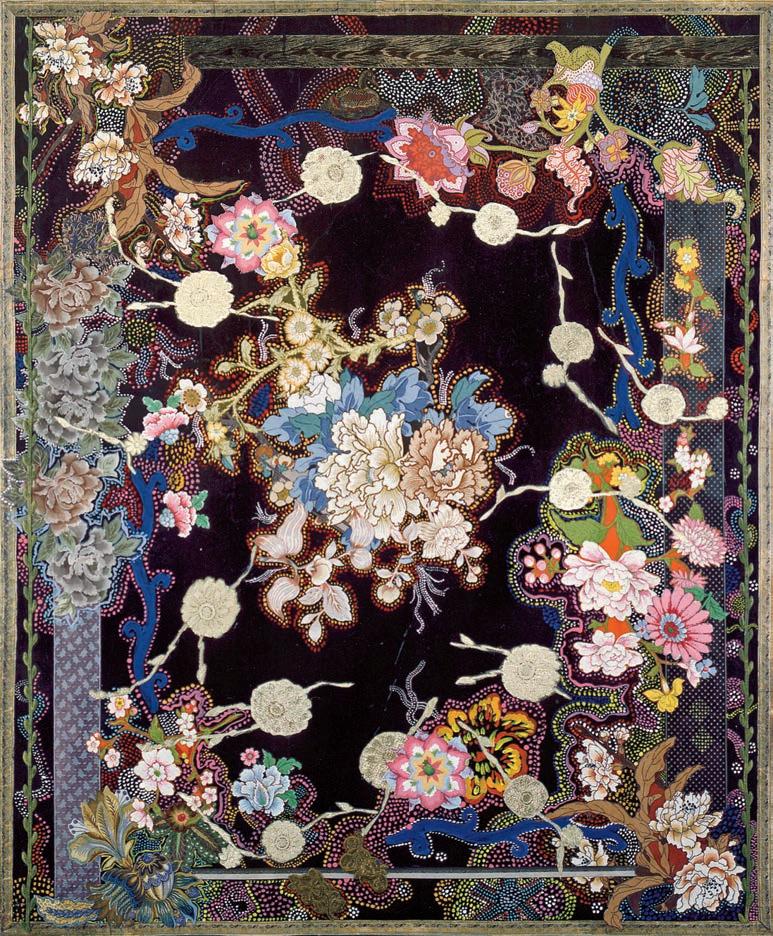

American (1923-2015)

What is Paradise, 1980

Acrylic and collage on paper

60" x 50"

1981 Acquisition

A flagbearer of Second-Wave feminism in the arts, Miriam Schapiro worked to recuperate diverse materials and techniques sidelined by the historical supremacy of painting and sculpture. “We really didn’t have any literature telling us it was a good thing to be a woman artist,” Schapiro said, and that “was something to get really angry about.” While the artist’s What is Paradise is an acrylic painting on canvas, the work breaks with pictorial conventions and repopulates painting with the feminized artistic forms of floral arrangement, mosaic and woven textile. Meticulous floral motifs, some smooth and others composed of many tiny tiles of paint, stand starkly against a black base. Schapiro adds ornamental columns and a rectangular border to frame the painting in further nods to the feminized sphere of decorative arts. Produced in the decade following her 1970s pioneering of femmage (feminist collage) and the success of the Womanhouse (1970) exhibition she co-organized with Judy Chicago, What is Paradise attests to Schapiro’s versatility as an artist.

Gladys Nilsson

American (b. 1940)

Course Line, 1975

Watercolor

12" x 15"

1981 Acquisition

Gladys Nilsson was a member of the 1960s Chicago Imagist group Hairy Who?

It was neither a movement nor a style but a loose collective of six artists who exhibited together at Hyde Park Art Center. Imagists like Nilsson enfold vibrant colors, bold lines, and psychedelic, urban imagery. Though their work was loosely unified in combining these elements, the Imagist artists of Hairy Who? took care to establish distinct individual styles. Nilsson distinguishes herself through the use of watercolors, rich tonal values and contorted two-dimensional human figures. In Course Line, Nilsson arranges several such tonally rich figures, informed by Indian miniatures and the ancient planar pictures common to the art of ancient Egypt and Greece. Nilsson said, “You can look at a piece of mine and think that it’s a benign exploration, but I like to think there’s an edge underneath it all in terms of certain commentaries on relationships. I’m an everyday person. … I’m not ruthless.” Despite the grand historical references and dramatic figuration Nilsson puts forth in Course Line, her attention to the “edge underneath” everyday relationships suggests that her distortive picture springs from humbler source material.

Jennifer Bartlett

American (1941-2022)

Untitled (Graceland Woodcut-State II), 1979 Woodcut

32 ¾" x 32 ¾" each

1981 Acquisition

Jennifer Bartlett is best known for prints and paintings in which everyday subjects — ranging from houses and gardens to oceans and skies — are visually reordered through scientific rule systems like the grid. This imposed structure allows viewers to focus on perception, process and the effects of shifting perspective. The three prints in the Reece Collection come from the artist’s larger Graceland woodcut series, a group of images that play with the common conception of a generic house — a recurring image in Bartlett’s work. But the title refers to no ordinary house. It references Elvis Presley’s Graceland Mansion in Memphis, a home that became the magnet for public attention in 1977 when the star suddenly died. Bartlett employs basic geometric shapes, such as squares, triangles and lines, for the five-color woodcuts, reducing our idea of the basic necessity for shelter into a two-dimensional form. In the first print, only the vertical lines are printed; in the second, only the horizontal lines are printed; and in the third, both the vertical and the horizontal lines complete the conceptualization of the form. Read from left to right, the works move fluidly from controlled, mathematical abstraction into a more painterly realism, a journey combining Bartlett’s artistic commitments to Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and Conceptualism. In a labor-intensive process, Bartlett cut the wood blocks herself. She wanted the prints to evidence their process of making and display their materiality. Of the medium, she said, “Woodcut is very direct. … It’s quite close to drawing.”

Howard Finster

American (1916-2001)

Heaven Is Worth It All, 1984 Enamel paint and mixed media on plexiglass

24" x 31"

1985 Acquisition