17 minute read

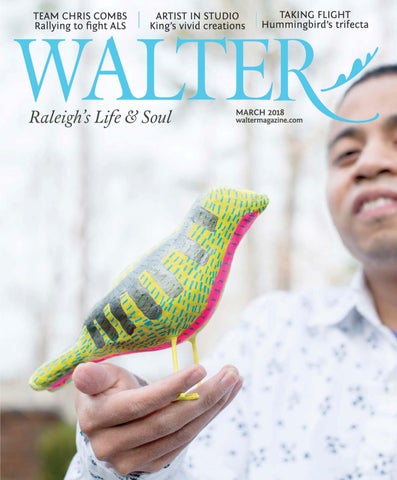

ARTIST IN STUDIO

King Nobuyoshi Godwin’s bright, layered paintings PATTERN MAKING

by SAMANTHA GRATTON photographs by LISSA GOTWALS

Advertisement

King Nobuyoshi Godwin’s mother, Yuko Nogami Taylor, helps organize his art business, including pricing the pieces affordably. Most of Godwin’s work ranges from $65 - $85, but his larger canvases can be as much as $700. Bright colors teeming with numbers fill the canvases that hang throughout the small but cozy studio with slanted ceilings. Two different songs from completely different genres play simultaneously – on a phone and through the speakers behind him. In the center sits King Nobuyoshi Godwin, silently painting as his aide and parents look on. It is a room full of unlikely but perfect pairs: colors with numbers, music on top of music, and an artist with autism.

As Godwin finishes painting a house on a recent weekday morning, he says it is having an “OK day” because “it is raining.” Next, he begins working on a blue canvas with a seahorse which is “71”. Godwin has painted hundreds of canvases, has his work in several retail spaces in Raleigh, and was awarded a merit award at last year’s Artsplosure. As his mother explains, Godwin’s autism isn’t a disability but an ability when it comes to his art. At just two years old, Godwin was diagnosed with autism. Now, at 26, he lives independently in an apartment and works as an artist. His life as an adult has structure and routine, because this is how he likes it best. Each day starts at 7 a.m. with a movie and breakfast. Godwin’s full-time aide, Lori Morgan, assigned by the Autism Society of North Carolina, arrives daily at 10 a.m. On Mondays through Thursdays, they go to his studio at Moondog Fine Arts to paint for three hours. The afternoons have a bit more variety, but still follow a routine. Mondays are for laundry, Tuesdays and Thursdays are for swimming. He cooks his own meals, watches a lot of movies, constantly listens to music, and loves to paint. Growing up, he attended public school with special programming, which was available to him until he was 21. From there, he went to UNC-Greensboro for one year to attend a program called Beyond Academics, which supports students with intellectual and developmental disabilities as they learn how to live independently and explore potential career options. Godwin was told his possible job choices included sorting items at a thrift store or stacking cans in a grocery store. Godwin’s mom, Yuko Nogami Taylor, also a painter, asked Godwin, “Would you like to do that?” No, Godwin felt it would be too easy. Wanting to find something that would challenge and excite him, they set out to figure out what he could do. After Taylor offered several options, Godwin chose painting. Together they went to a bookstore and scoured magazines as she asked him what style he wanted to paint.

Aide Lori Morgan, Yuko Nogami Taylor, and artist King Nobuyoshi Godwin showcase a favorite piece (“The bird is having a great day because it has pretty legs and flying above the cloud 71”) that is hanging in the home of N.C. State Chancellor Randy Woodson.

Godwin picked something with bright colors and repeating shapes (far different from Taylor’s own style). He started small with colors and circles. One day, Taylor told her son that he needed to put feelings in his paintings. That’s when the numbers started to appear. While Godwin does speak, he typically only responds with two or three words. It was once Godwin started painting numbers at the age of 22 that his parents began to understand, for the first time, that Godwin’s thoughts and emotions are best felt and expressed through numbers and colors. Upon first glance at a piece by Godwin, the numbers may seem more like texture in the painting. If you look closer, you will see that every inch of the canvas is covered in painted numbers. The numbers are not based on a linear scale rating his feelings from bad to good; they are based on a pattern and a connection, known only to Godwin, between both the colors and numbers. Purple and yellow are the happiest. Orange is positive. Numbers 11, 15, and 71 are often used and are all good. Red is not so good. And seven is bad – written as 07, it is not to be confused with 77 repeated on the painting, which is good. “You can really see his humor in some of the paintings and the titles that he gives the paintings,” says his father, Thomas Taylor Jr. Godwin’s parents say their son’s art has helped them experience more of his personality. They understand Godwin’s perspective better now through his paintings. Godwin has a specific creative process and a routine when it comes to his art. He readies the canvas with an initial coat of brightly colored acrylic paint. These color schemes were not taught to him; he knows them and feels them intuitively. He speeds up the drying process by using a hair dryer, eager to move on to the next stage. In another bright color, Godwin meticulously draws the animal, plant, or object to be the subject of the piece. Every line is delicate and precious, painted until it “feels good” to him. Many of the animals or objects have faces, but usually with mouths drawn in straight lines. Morgan says she thinks this is because those with autism have a harder time reading facial expressions for emotions. Then, Godwin uses bright Japanese paint pens to number everything, sometimes using different numbers throughout different sections of the canvas. He frames and names each piece of artwork before it goes up for sale. “He paints every day with the same level of enthusiasm because he truly loves to make others happy with his art. All of his creations are a testament to the type of person that he is,” says Morgan.

Godwin relies on the support of those around him, including his mother, pictured above, who is also an artist. She offers creative advice, such as suggesting materials and paints that best suit his work. “King has the kindest soul and his mere presence will light up a room.” As soon as he arrives at his studio each day, Godwin starts listening to several different sources of music. Whether at home, in the car, or in his studio, he plays songs in multiples, listening to several songs from different styles and genres at the same time. Sometimes he has up to five devices playing simultaneously. Instead of sounding like overstimulated noise, it truly sounds like a new form of music. Music is not only a part of Godwin’s creative process but also a significant part of his life and his upbringing. His father is a jazz drummer, whereas Godwin plays Taiko drums as a part of a ceremonial Japanese drum performance group. And his memory is uniquely tied to music. Godwin remembers exactly what situation happened with a specific song, even with a library of thousands of songs to choose from. There is a reason Godwin’s work looks completely original. While Godwin may not often speak verbally, art is how he expresses himself. His autism shapes his paintings with his unique perspective and voice. At 26, both of his parents say Godwin is proud of who he is and knows his strengths. The painting is simply evidence. As his father says, “He doesn’t have to say much to make a great impact.”

Godwin’s work can be found locally at HandmeUps, Lucky Tree, Moondog Fine Arts, and Read With Me. His newest collection is on display at Artspace through April 28.

THEUMSTEAD.COM|CARY,NC|866.877.4141

CUCUMBER GLEANING

Jason Brown hung up his NFL uniform and returned to his home state to purchase First Fruits Farm. The farm grows and then donates crops like sweet potatoes, cucumbers, and watermelons.

CALLED to CULTIVATE

Jason Brown grows food to donate, not to sell

by IZA WOJCIECHOWSKA

Every fall, Jason Brown welcomes thousands of volunteers to First Fruits Farm in Louisburg, North Carolina, who roam the farm’s 20 acres plucking sweet potatoes out of the freshly plowed earth. In this way, Brown collects hundreds of thousands of pounds of the crop – and every last one goes straight into the community. First Fruits is a donation-first farm, which means that the priority is not to sell produce, but to give the first crops of the season away. To date, Brown has donated more than 800,000 pounds of sweet potatoes to those in need across the state.

GOLDEN HOUR

Jason Brown’s First Fruits Farm relies on volunteers to harvest their produce.

First Fruits Farm works with more than 100 community organizations, including the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle, Food Bank of Central & Eastern North Carolina, the Society of St. Andrew, and numerous local churches, soup kitchens, and food banks to provide hunger relief to thousands of people. But Brown’s path to farming, and to good works, was unconventional. After graduating from UNC-Chapel Hill, where he was a star football player, he was drafted by the Baltimore Ravens. In 2009, he signed with the St. Louis Rams, where he became the highest-paid center in the NFL. Three years later, Brown, a devout Christian, felt a calling; he decided to leave the football field to tackle issues of food insecurity in his home state instead. Without any real farming experience, he and his wife, Tay, a dentist, purchased First Fruits Farm in 2012 and got to work. “People often say to me, ‘If you had continued playing football, you could have made millions of dollars and purchased more food and given it away than what you’re doing now,’” Brown says. “But you can throw money at problems and they’re still going to persist. If we’re truly going to seek change, it’s got to come from our hearts, and that’s what’s made all the difference.” Sweet potatoes are First Fruits Farm’s main crop because they’re nutrient-rich and easy to cultivate, harvest, and store. Brown also grows cucumbers, watermelon, and corn, and he hopes to soon start growing muscadine grapes, which have been shown to have high antioxidant content and significant health benefits, he says. This spring, the farm will also reprise its Sow a Seed program, which saw success in 2015 and encourages people who may never have farmed before to grow their own vegetables. Brown packaged seeds for corn, watermelon, squash, cucumbers, and tomatoes to mail to anyone who requested them and sent seeds to hundreds of people across the United States and abroad. “The idea is if Jason Brown, some kid from the country who plays a little bit of football, can grow some food, then you can do it too,” he says.

Jamie Thayer-Jones (PORTRAIT); The News & Observer (POTATOES/GLOVES) Brown grew up in Henderson, an hour north of Raleigh, where his father was a landscapist and taught Brown to mow lawns and plant trees. Though his father had himself grown up on a farm, he left home at 18 and never looked back at that lifestyle. Now, Brown is learning that farming is a completely different experience from landscaping, but one that’s been very rewarding. He says he wouldn’t trade it for anything – even his football career. When he reflects on his decision to leave football – at a time when his three dream teams were ready to sign him, at that – he credits it largely to his faith and conversations he had with God, who called him to help others. But at the same time, he was also coming to terms with personal tragedy, which eventually became an inspiration, he says. When Brown was 20, his brother, Lunsford Bernard Brown II, was killed at age 27 in Afghanistan, where he was serving with the U.S. Army. “When I turned 27,” Brown says, “I was at the peak of my game, the peak of my career, financially successful.” But he woke up that morning of his birthday and found himself having a quarter-life crisis and comparing his own life to Lunsford’s. “There was no comparison,” he says. “He had lived a life of service, and I was living a life of fortune, fame, and entertainment. So I just really began to reflect on what I learned when I was a child growing up in church: Love thy neighbor. But what does that look like?” Brown decided to follow the calling and honor his brother’s life, and says it was one of the hardest decisions he’s ever had to make. Learning to farm and maintaining the crops has not been easy, either. He and Tay run the farm with only the help of volunteers, and they’re raising six children, with a seventh on the way. “It’s been a very interesting journey,” Brown says, “but it’s really turned into something beautiful.”

GREATER PURPOSE

First Fruits Farm donated its first harvest of sweet potatoes in 2014. Above, Jason Brown repurposes his NFL equipment to work on his 1,000-acre Louisburg farm.

YAM ON

Here’s how to support First Fruits Farm’s efforts locally.

Society of St. Andrew of the Triangle

The ecumenical nonprofit seeks to “meet people’s hungers,” physical and spiritual, by providing volunteer opportunities related to hunger relief. The group’s volunteer-driven Gleaning Network coordinates with statewide farmers and food providing agencies to act as a go-between. Groups from the Triangle regularly volunteer at First Fruits Farm, and also deliver sweet potatoes to shelters and kitchens locally. endhunger.org/north-carolina

N.C. Study Center, Chapel Hill

The Christian nonprofit next to UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus works to activate and empower college students. Jason Brown donates 40,000 pounds of sweet potatoes to the group’s annual Yam Jam in February, among other collaborations throughout the year. ncstudycenter.org

Volunteer directly

You can sign-up for time to volunteer at First Fruits Farm most any time of the year. There are opportunities to harvest sweet potatoes, and also: greenhouse work, seed planting, harvesting crops year-round, fishing derbies to harvest fish for donation, meat processing, carpentry and farm upkeep work. wisdomforlife.org/volunteers

CLASSICMODERN

by CC PARKER

FAMILY FUN

Above: Sara Parks and her son Braxton conquer the Fuji crossing.

LEARNING the ROPES

Finding perspective at one of Raleigh’s treetop courses

by JAMES HATFIELD

AERIAL VIEWS

Right: Leah Kipps enjoys one of the many ziplines at Go Ape.

At the back of a gravel parking lot in Blue Jay Point County Park is the log-cabin headquarters of Go Ape treetop adventure course. The quaint wooden hut is about the size of a beachside frozen ice stand, and it has a drive-through style window in its front. It reminds me of refreshing cool drinks during relaxing summer days on the beach. Unbeknownst to me, it is actually the launchpad of a grand undertaking, a far cry from relaxing on the beach. I recently visited the site in search of fresh air and a bit of adventure. I found both in spades, all tucked away in the North Raleigh park.

The experience

As soon as my companions and I arrive at Go Ape, I hear the joyful cheers of children, plus a couple of pitiful wails from adults on zip lines; I knew we were in the right place. I should mention that I’ve always been afraid of heights. My hope is that this excursion will cure my fear via overexposure. This screaming, however, does not help. I steel myself and keep moving forward. Luckily, the attentive staff pays attention to party allegiances: If you, like me, attempt this with your friends and family, the staff will stagger your course set-off accordingly. This further assuages my fears, as at least no strangers will witness any profound lacks of balance among the trees. The adventure begins with a 30-minute in-depth safety briefing, during which we practice walking along a wire strung between two trees. For this demonstration the wire was only four feet off of the ground. Next up: the 50-foot course. During the safety briefing, I had to ask: Has anyone ever fallen? Thankfully, the answer was a resounding “no.” This might be because, also thankfully, the instructors will coach you from the ground throughout the course if you need help. The security briefing is so clear and concise that you have all the tools you need to complete the course. For me, they were still moral support from below. Primed and ready, we set out on the first of the course’s five segments, called “sites.” Each site starts with a ladder from the base of a towering tree to the starting platform. Advancing to the next tree’s platform is where the challenges lie. There are four to five different obstacles at each site, from a single tightrope style wire to traverse (much scarier than that four-foot-elevation safety demonstration), to a series of X-shaped wooden swings in a row that you must leap-lunge-hop along. Each site’s reward is a jaunty zip line ride to the ground. After the cheers of accomplishment subsided, we dusted the wood bark out of our shoes and walked along the trail to the next site. With each new site, the route from ladder to zip line becomes increasingly more challenging. By the time I approached Site Five, something like shimmying through a hole drilled in the middle of a suspended wooden platform, fireman’s-pole-style, felt like business as usual. I felt confident, ready to finish this course strong. And then I saw the net. Before me, about 30 yards out, was a giant net of ny-

lon rope hanging like a sheet on a clothesline. There was no structure bridging the gap between me and the net, only a single thick cable dangling at the end of the platform with a giant clip secured to it. A sign next to my head encouraged me to utilize the “Tarzan Swing,” and its accompanying pictorial guide showed a silhouette clipping to the single dangling cable, and then climbing the net. Just in case I misunderstood: “How do I get to the net?” I asked our coach below. She looked up and smiled, “Just…walk off.” The time for conquering fear was now. I held my hands and started up to jump – and then, honestly, I clung to the rope for dear life, screaming pitifully. I scaled up the net, pulled myself onto the next platform, and continued to the last zip line stretching across the entire parking lot. As I glided over the parked cars I could see the entire course and its horseshoe shape, and how it doesn’t end far from where it began. I really did ease my fears by facing them, by tackling these obstacles. It might be in the name of fun and adventure, but this ropes course has solid life lessons to offer, too.

SKY HIGH

Brent Hazelett and Ashleigh Groff, above, suspend from Jamor Crossing.

OTHER OPTIONS

There are a few local places to test your treetop aptitude:

Go Ape

Open March – December; $38 ages 10 - 15, $58 ages 15 and up; 3200 Pleasant Union Church Road; goape.com/ locations/north-carolina/raleigh

TreeRunner Adventure Park

Open March - December; $39 ages 13 and under, $44 ages 14 and up; 12804 Norwood Road; treerunnerraleigh.com

City of Durham Courses

There are low and high ropes options; $25 - $60; durhamnc.gov/2809/ ropes-courses

Bond Park

Open by reservation only; $35 - $75; 801 High House Road, Cary; townofcary.org