5 minute read

MUSIC: An Old Soul

MUSIC

Charly Lowry on the banks of the Lumbee River

Advertisement

an OLD SOUL

Charly Lowry defies classification as performer with Indigenous roots

by DAVID MENCONI photography by JOHN GESSNER

“Sometimes I’ll meet audience members after a show and they’ll say, I thought there’d be flutes or more native drums or something,” Charly Lowry says with a laugh. “It’s been a journey to break down stereotypes and educate people, especially because I don’t look like what non-natives think a native looks like. But I grew up listening to everything.” An Indigenous singer of Lumbee/ Tuscarora descent, Lowry was born and raised in the town of Pembroke, where she lives on land that has been in her family since the late 1800s. Her speaking voice carries a drawl that’s pure Down East, and her singing voice is powerful and soulful, with an occasional slide into a country music-style warble. Lowry might occasionally play a hand drum onstage, but if you see her singing with her rock band, Dark Water Rising, it’s obvious that she’s influenced at least as much by pop singers like Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston as she is by Native American music. Lowry wanted to be an entertainer as a child. By her middle-school years, she was telling anyone who asked that her main career choices were singer, veterinarian, or basketball player in the WNBA (she says her 5 foot, 4 inch frame made the latter dream unrealistic). Singing held the most promise. Lowry was 12 years old and had just been voted “Junior Miss Lumbee” by her nation when she met Pura Fé, a Tuscarora/Taino singer who was al-

MUSIC

ready well-established in Indigenous music circles. Lowry impressed Pura Fé immediately. “Charly really stuck out,” says Pura Fé, “very talented and beautiful, inside and out.” They eventually became collaborators in her acclaimed voice-and-drums ensemble Ulali Project. “She’s great, very quick musically, and a great singer and person, just topnotch,” says Pura Fé. “She can be very bluesy and soulful with no limits. I think she’s still just tapping into a very deep well. She has not yet gotten to even half of what she has in her.” Lowry was in college at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the early days of the singingcontest show “American Idol,” which

she watched avidly. She auditioned for 2004’s third season (ultimately won by High Point’s Fantasia Barrino), one of almost 100,000 entrants nationwide. A fiery version of “Proud Mary” was her calling-card performance, and it earned her the coveted “golden ticket” to the Hollywood round. But Simon Cowell, who had a reputation as the show’s naysaying “mean judge,” almost derailed her. “He said, Well, you’re a pretty girl, but you’re a bit old-fashioned,” Lowry says. “That’s what he said instead of saying I’m an old soul, which I’ve come to find out I am. And I’m from the country; we do things a little slower than mainstream media and TV is used to.” Lowry was one of 117 contestants to make the Hollywood round and got as far as the top 32 before being voted off, after which she went back to UNC. But with “American Idol” on her résumé, she was hearing from area producers and musicians. One of them, Aaron Locklear, became her longtime bandmate and collaborator in various groups, including Dark Water Rising. They were gigging regularly and putting out records by her senior year, with plans to keep going. Unfortunately, a number of calamities slowed Lowry’s momentum, including serious health problems. She has had two kidney transplants over the years, the most recent one in 2020. During the years she was on dialysis, she moved back to be caregiver to her ailing mother, who passed from cancer in 2017. And the pandemic put a serious crimp in her performance schedule the last couple of years. But through it all, she’s stayed active with her various groups, often in educational settings as an “artivist” — an activist as well as a musician. She played the Governor’s Mansion for a 2019 “Music at the Mansion” performance as part of the state arts council’s Come Hear North Carolina program, bringing the music of eastern North Carolina to life. And her online livestreamed shows during the pandemic

included an October 2020 “Songs of Peace and Justice” program presented by the city of Greensboro’s Public Library. “She’s awesome,” says Rhiannon Giddens, the Grammy-winning MacArthur Fellow, who connected with Lowry when she opened Giddens’ 2019 performance at the North Carolina Museum of Art. “What a voice, what heart, what soul. I love her to pieces and want the rest of the world to know about her, too.” In terms of career longevity, it should help Lowry’s cause that she is a versa-

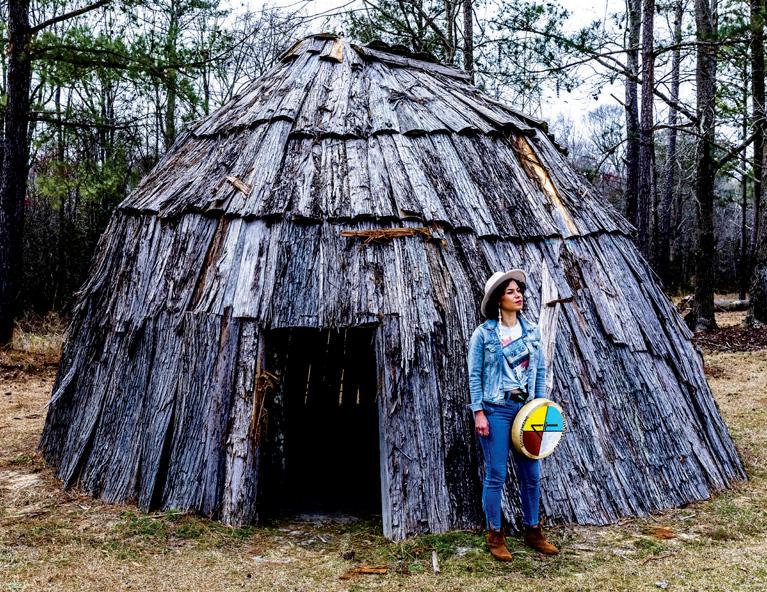

Lowry with A hand drum given to her by Pura Fé

— Rhiannon Giddens

tile singer who can handle pretty much any style convincingly. As she notes, nobody knows how to classify Dark Water Rising, so they often wind up in the “roots” or “folk” categories. “I don’t consider myself ‘folky,’ but I’ve been invited to play at the Folk Alliance International conference,” she says with a laugh.

It has been a few years since Lowry has released any recordings, but that should change if things go according to plan. She’s going to put that multifaceted versatility on display.

“This year, I plan to hone in on a bunch of different genres with a series of records,” she says. “I’ll do one called Charly Goes Country, then Charly Goes Soul, Charly Goes Gospel, or Charly Goes Indigenous. I’ll do my best because this is my life. Music is my baby and I can’t focus on anything else. There’s not enough time or energy for anything else.”

Lowry at the Lumbee Cultural Center in Maxton

SEE THE SHOES EVERYONE IS RAVING ABOUT… ONLY AT MAIN & TAYLOR