13 minute read

Clinical Poetics:The Good

Clinical Poetics

A D.C. nonprofit makes poetry out of the stories of nurses, doctors, and patients.

Advertisement

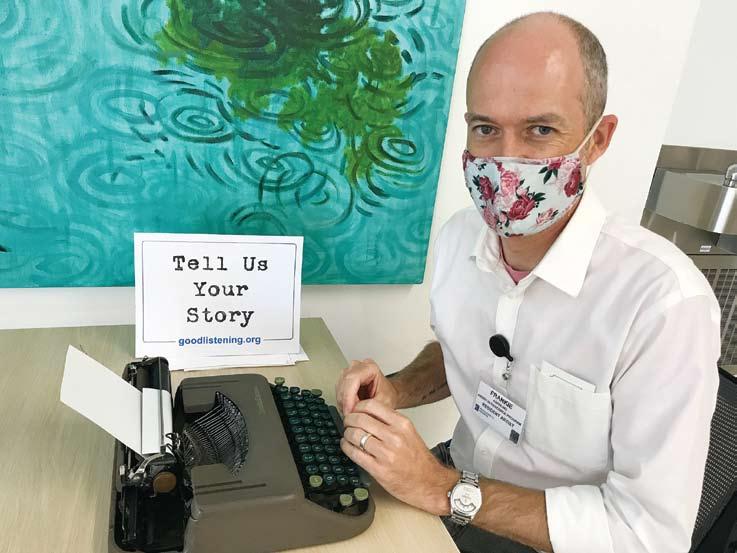

Frankie Abralind

By John Anderson

Contributing Writer “The word tender comes to mind,” says Tamara Wellons, who manages the artist in residence program at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute in Fairfax. In a space on the second floor, near the elevators and escalator, a person sits at a table with a typewriter and an open chair across from her. Two signs read “Listener Poet” and “Tell Us Your Story.” Anyone is welcome to sit and tell their story, Wellons continues. “A caregiver, staff member, or patient: on site, it can be a security guard. It can be anyone in the space who wants to sit down and be with the listener poets.”

Schar’s AIR program is a partnership with Smith Center for Healing and the Arts, a D.C. nonprofit that creates most of its programming to support patients and caregivers dealing with cancer. A variety of artists participate: painters, knitters, musicians. It also includes The Good Listening Project, a D.C.-based nonprofit that sends listener poets to hospitals and medical conferences—in person or, now, remotely. They listen to doctors and nurses, and write poems for them based on their conversations.

The Good Listening Project is the brainchild of Frankie Abralind, an experiential designer and experienced listener, who wants to be part of the solution to reduce staff burnout in medicine. What was once a weekend art project got reinvented through his job as a designer in the Sibley Memorial Hospital’s Innovation Hub— plus business trips and chance encounters at Burning Man. While anyone who sits with The Good Listening Project receives a poem, in the end, what they get from the experience is something far greater: the opportunity to be heard. The project has roots in a business trip to New Orleans in 2013. Abralind saw numerous poets busking in the French Quarter the way musicians might—typewriters their only instruments. “I was immediately captured by that idea,” Abralind says, “because I love talking to strangers, and I had this confidence that I could write a poem.”

He’d never seen a poet busker in D.C., so when he returned home he became that guy, minus the tip jar. He called it Free Custom Poetry. Accompanied by a friend, a folding table, two typewriters, and a bag of paper, they’d set up near the National Air and Space Museum and write poems for interested tourists. Abralind would then photograph the people—his poemees, as he called them—and write brief notes about each poem. But the fun wasn’t just giving writing away: It was in the connection, the empathy.

For a long time, Free Custom Poetry was just a hobby, though. In 2016, Abralind began working in the Innovation Hub at Sibley Memorial Hospital. The Hub worked to solve staff-led problems via design thinking: a way to solve problems through ideation, prototyping, and user testing. They might create devices, like 3D-printed hooks to carry walkers on the back of wheelchairs when transporting patients, or they might work on more abstract issues, like creating an illustrated guide to better communicate the importance of case coordinators.

That summer, Abralind asked his co-worker, Andrew Yin, if he would be interested in joining him on the Mall to write poems for tourists, as he’d been doing for years. “He said, ‘I know you really like listening and hearing people’s stories,’” Yin recalled. Abralind described it as a creative way to listen to people’s stories and translate them.

Poem-writing frustrated Yin at times, but he remembers most encounters fondly, like the poems he composed for a pair of women who just graduated college. “I got to write this poem about getting older, growing up, and becoming adults,” Yin reflected. “As they walked away, I saw them turn to each other and give each other a hug, and just be so happy to be with each other. It was totally amazing to see that reaction.”

Back at work, their boss, Nick Dawson, saw photos of Yin and Abralind’s outing. He asked why Abralind hadn’t done it at Sibley. Abralind hadn’t considered it. On a day off, Abralind went to work and set up his typewriter, expecting to write poems for patients. Instead, staff sat down. They discussed giving diagnoses, or concerns about burnout, among other things. It dawned on Abralind how well Free Custom Poetry fit in a hospital setting: He wanted to make it a program.

Burnout, which came up often in the sessions, is a major concern in medicine. “Nurses want to leave after the first year of being a floor nurse,” says Suzanne Dutton, a geriatric nurse practitioner at Sibley who earned her Doctor of Nursing Practice studying burnout. Dutton first met Abralind in the Innovation Hub, creating a whiteboard questionnaire to assist nurses dealing with patients who had delirium and short-term memory issues.

According to one recent longitudinal study, pre-COVID, 31 percent of registered nurses will leave after the second year and up to 55 percent will leave within six years. Dutton mentions other factors, such as patient to nurse ratio, staffing shortages, patient suffering, and challenges with institutional and ethical issues. But for her, burnout was also a lived experience. After 15 years as a nurse practitioner, it got to be too much. She had been on-call 24/7 for 1,000 geriatric patients. “I considered leaving and becoming a pastry chef,” she says. Instead, Dutton took a different job at Sibley. Chance encounters at Burning Man made it possible for Abralind’s project to get off the ground. In 2017, the festival provided him with a summer intern; in 2018, it gave him a pro bono grant writer, a benefactor, and a co-founder. By the end of 2018, he’d officially left Sibley and started an independent nonprofit called The Good Listening Project with Kay McKean, a leadership coach who balanced her organizational strategy and long-term planning against Abralind’s mission development and sales.

“Poetry is the how of what we do,” says McKean. “Listening is the why of what we do. From the beginning, we always had the presence of listening: That is where the healing comes from.”

Listening has a multitude of benefits. Good listeners make for better doctors and nurses: They can get better information, make better diagnoses, and retain the trust of patients and their families. When Abralind recruits listener poets, he looks for people with high emotional intelligence—people who know how to listen; he doesn’t care if they’ve been published. “One of my earliest team members had a master’s degree in counseling and had not written more than five poems before she started working with us,” he says.

In 2019 and 2020, The Good Listening Project’s setups at SXSW, an American Nurses Association conference, and the International Integrative Nursing Symposium were similar to Free Custom Poetry: a table, a typewriter, a sign. “We never call over people,” noted Abralind. “People always selfselect.” Still, they might pass the table three or four times in a day before choosing to sit down. Participants who approached the listener poets sat with them for 10 or 15 minutes to tell their stories. After a session, poemees might linger as the listener poet jotted notes or began to compose the poem. But unlike Free Custom Poetry, these poems aren’t intended to be written in 15-20 minutes; they’ll be emailed within 24 hours of a listening session.

“You have to go into the conversation with the right energy,” remarks Elle Klassen, who met Abralind at Burning Man and interned with The Good Listening Project during its nascent days at Sibley. “I have to have a neutral energy so that people can share something really positive or really negative.” Throughout a session, she remains calm and leaves space for silence, to let the participant have the time to collect their thoughts. “If I was too positive, participants might not talk about heavy topics.”

After listening to someone, McKean takes notes of the words used, elements of the story, and the overall experience. “If I have to step away [from the poem], when I return to write the piece, what I pay attention to first is the feeling we shared in that space.”

“The process of listening and writing the poem is really about staying in that place of presence and not breaking it,” says listener poet Jenny Hegland, a trained therapist who began contracting with The Good Listening Project in 2019. “Sometimes the poems just come,” she notes, mindful not to let too much of her interpretation overshadow the words of the poemee. She also admits there are poems that take hours to craft. “It is a delicate art to take someone’s words and reflect it back,” she says. “If there was no deadline, it might take forever.”

After receipt, some participants might request a rewrite of the poem. All participants are informed that their poem may be used in a publication, anonymized, but that they have the option to opt out. Few do.

Not all poems are about health care. “I think people expect all our conversations to be about illness, disease, cancer,” Abralind says as he reflects on poems about trips, world politics, moving to D.C., and commuting. “The reality is patients are people first. Staff are people first. The first thing that comes to their mind might be completely orthogonal.”

After The Good Listening Project completes a contract with a hospital or conference, they create collections of poems, each roughly 140 pages. Only half of the pages contain a poem: The other half are notes about the poems. For example, one of Abralind’s poems uses a river as a metaphor.

There’s never been a way to stop

The river Gabrielle

The rocks, and dams, and ice blockades

That have made her feel unwell

Have only served to redirect

She finds another way

To trickle, flow, to carve out, roar,

And thrive another day

The opposite page clarifies the obstacles were three cancer diagnoses, and the patient’s definition of resilience is not just to survive, but to thrive and use the opportunity to grow.

Other poems are more direct. “Mauricio” by Ravenna Raven, the only trained poet among the listener poets, begins:

He’s the best dad ever, even when we’re not together. I was gone for five days but he was never worried, though the baby started teething and the two-year-old stopped sleeping…

“As listener poets we are not writing for anyone but that one person,” Abralind reflects, noting that the motivations of his Listening Poets are not to get work into journals or the New Yorker. “Is it the best poem ever written? Yes—for that one person. That is our hope.”

As part of their follow-up work, The Good Listening Project solicits feedback from participants. One patient’s testimonial debated whether the best thing about the day was the poem or learning the shadow on her liver was benign.

Dutton, the nurse practitioner who’d studied burnout, brought The Good Listening Project to her unit at Sibley for Nurses Week in early 2020. As she made her rounds and told nurses where to get a poem, she overheard one say, “That was the best part of my whole month.”

Rosemary Trejo was one of the nurses who took part. “I thought if Frankie was leading it, then I want to do it,” she says. She previously sought Abralind’s help in the Innovation Hub to create a bag to carry awkward patient-controlled analgesia pumps when moving patients. “I always thought he was a great listener.”

Trejo spoke with Abralind about her evolving relationship with her mother as she becomes her mother’s caretaker, coming to the U.S. from El Salvador, and the sacrifices she and her husband made for their kids. “He tapped me into a space that I have not tapped in—being a mother and career woman, all these different roles I have carried.” Throughout, she listed accomplishments that she never stopped to give herself credit for. “He captured it, and put it in a poem. And when I reflected, I thought, ‘oh my God, that’s incredible!’”

“I do know some other people have their poems hanging up,” she says, but Trejo’s poem is no longer available to her. It lives in a locked drawer; the office space she once inhabited is now part of the hospital’s COVID unit, storing masks and other PPE. “I have moved so many times already. I hope it’s still there.”

At the beginning of 2019, Abralind’s hope was to be able to reach 100 hospitals by the third year of the nonprofit. 2020 seemed equally hopeful. Then the pandemic hit.

“That one week at the beginning of March, [Schar] said we aren’t allowed into the hospital anymore,” Abralind recalled. “The next week, we had our Zoom set up.”

“The Good Listening Project pivoted quickly,” according to Wellons. “Frankie worked really hard to get things going online so people could do it virtually.” She recalls the signs and vouchers for staff at the Schar Cancer Institute to connect. The Good Listening Project continued to iterate on its remote capabilities through the spring of 2020.

Because of The Good Listening Project’s online programming, the American Association of Medical Colleges recently collaborated with it—as well as StoryCorps and 55-Word Stories—on a story-sharing activity. Virginia Bush, a medical education project manager for the AAMC, calls it “a perfect fit.”

“The listener poet work highlights the therapeutic effects of telling a story during a time when many were isolated and scared,” Bush says. Partially funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, the activity supports AAMC’s Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education initiative. Bush cites a growing understanding of how incorporating arts and humanities into hospitals helps with empathy, communication, and observation skills when doing patient intake. “The hard sciences only go so far.”

The pivot to online also enabled other advantages that will likely outlive COVID restrictions. Affordability is one: Clients don’t have to pay for the costs of travel. Access is another. “[With Zoom] it doesn’t matter if you are working from home or at the other end of the building, or the night shift,” Abralind says. “You can sign up for a slot and talk with one of our listener poets.”

Predictability has been another advantage of Zoom. In person, the number of participants would fluctuate. People, unaware the service was on the hospital campus, might only be lured by what Raven called the anachronistic sound of the typewriter. Remotely, “because people sign up ahead of time, you know your schedule,” Raven says. “People get reminders about their sessions, so it’s a lot more formal. Very few people don’t show up at all.” Additionally, the contracts are now shared among who is available, instead of sending one contractor to one location. “On one given day a listener poet might be talking with participants from three or four different clients in three or four different states,” observed Abralind.

While Abralind can make an argument for continuing to use Zoom beyond 2021, Dutton knows that there are still benefits to in-person sessions. “So often nurses will say they don’t have time. ‘I can’t get off the unit. I can’t get a break. I don’t have time to eat lunch.’ They’ll do that and not make time for themselves,” Dutton says. That’s why she brought the project into her unit at Sibley: All her nurses had to do was round the corner. Nurses could simply ask one another to cover patients for 10 or 15 minutes.

Trejo’s in-person listening session with The Good Listening Project was, overall, a learning opportunity. “[As a nurse] you’re running around and have to do 10 other things.” She incorporated what she experienced during her listening session into how she works with patients: “I have tried to be a better listener.” On rounds with physicians she’s mindful, sits to talk with patients, and maintains eye contact. “I think it has been effective. Your mind is still racing, but I try to be present. I take a deep breath because it is about them.”

John Anderson