8 minute read

Arts Club:Randall and

Drivers are battling new external factors, and some restaurants are doing to-go food for the first time and might take longer to fulfill orders, so customers should be patient. “We’re so used to instant gratification—where food is at your door within 30 minutes without fail,” Sarah says. “So when that doesn’t happen, we’re so quick to blame each other or not tip someone.”

Long waits for small orders are a big frustration for drivers. Ahmad, a former rideshare driver who asked to be identified only by his last name, tried Uber Eats, but determined it wasn’t worth the trouble after a bad day at the McDonald’s on 14th Street NW. He accepted what he thought would be a quick order guaranteeing him $3.25 from Uber Eats. But then he was stuck waiting under the Golden Arches for 25 minutes. With a $2.75 tip, he netted $6 for 30 minutes worth of work.

Advertisement

For former delivery driver Ca it l in Schiavoni, finding parking was the biggest time suck. She drove for most companies, but found Caviar the most favorable. “Customers can track couriers,” she says. “‘Why is this idiot going around in circles? Why haven’t they stopped and given me the food?’ Because they can’t find somewhere legal to park!”

When Schiavoni sensed her tip money was slipping away, she’d park illegally, hoping to slip in and out unscathed. “There were so many times I’d run out to them putting a ticket on my car,” she says. She wishes the city would grant permits to delivery drivers so they could park in loading zones and other designated areas. “It would solve so much anxiety about parking and money issues.”

Parking wasn’t the only problem. When Schiavoni pulled up to residences, customers wouldn’t always pick up the phone. “They’re showering, they took their dog for a walk, or they fell asleep,” she says. “I can’t tell you how many times I got somewhere and called and called. Did you not think I was going to try to go fast? That’s the whole point of me doing this. The whole time you’re waiting, you’re losing money.”

Schiavoni, who has also worked in restaurants, isn’t sure people ordering on apps know drivers depend on tips for the lion’s share of their earnings. “To get a good tip depending on how far you’re driving, you need to accept something over $35,” she says. “Just like serving, you don’t want to serve somebody who only orders a Coke and sits there for two hours.”

Some platforms assign drivers a score based on a number of factors, including customer ratings and percentage of deliveries accepted. Schiavoni knew how to work the system, but could only control so much. “I’d try to wait for a big one, and I’d decline 10 little ones. But I’d have to take a small one eventually or my score would go down,” she says

Schiavoni says she “got stiffed” on tips more frequently as a delivery driver than as a restaurant worker. “Or they only give you a couple of dollars for delivering large orders,” she says, noting she was tipped in cannabis once, but gave it away. “That’s when you fall back on delivery fees, which you don’t always get all of. You’re not making hourly. People don’t treat it like the tip model that it is.”

One bad delivery can throw off a whole day’s wages, especially because some delivery apps permit couriers to complete multiple deliveries at once. “If you have three deliveries to pick up and you get a call that the first one gave you the wrong food, now you have three [orders] that are late because you have to go back to get the correct food,” Schiavoni continues. “Then you have three customers who don’t tip you.”

Drivers can predict when they’re going to get slighted. “I had to go to Toastique to pick up one juice,” Sarah says. “As soon as I got it I was like, ‘I’m definitely not getting tipped for this.’” She delivered it three blocks away and left it on an empty desk as she was instructed. During the COVID-19 pandemic, couriers offer contactless delivery to minimize interaction. She was right. “I understand you want the convenience, but why won’t you tip?”

Even though contactless delivery is now the norm, Sam still wants to provide good service. He estimates that 50 to 60 percent of his Caviar income comes from tips. “As much as I don’t like random calls from people, I’ll text the customer and say, ‘Enjoy and be safe,’ to add some modicum of a human element. Otherwise it feels like a ghost is dropping off your food.”

He’s intrigued by the new DC To-GoGo grassroots delivery platform that the owners of Ivy & Coney started earlier this month. Its goal is to provide an alternative to third-party apps that puts more money in the hands of restaurants and delivery drivers. The middle membership tier involves restaurants hiring their own delivery drivers—ideally employees they’ve laid off. DC To-GoGo asks restaurants to pay these drivers a base wage of $18 an hour.

“If they can sustain that, that’s incredible,” Sam says. He thinks only restaurants that crank out orders can afford to pay that much. “I don’t know that the average restaurant, especially on a weekday, can handle that.”

While hyperlocal alternatives to traditional delivery services may respond to some of the injustices of the job, the reality is the industry suffers from what Georgetown’s Wells calls “the Titanic problem.”

“These workers have been told the automated vehicle is coming and their jobs are going to disappear,” she says. “The thought is, why unionize the engine room while the ship is sinking? Why work to fix these jobs if they’re going to disappear anyway?”

It’s a dejected feeling shared by delivery drivers, including Tony. “Nobody wants me to make a good living just delivering food,” he says. “All these things are done to make it cheaper for the customer.”

While drones are currently prohibited in D.C., Tony doesn’t think it’ll be long before he’s replaced by one. “The lobbyists will get that taken away,” he says. “Jeff Bezos lives here. In the future, maybe chefs will have a personal touch for food that you can’t replace. But as far as delivery—we can be replaced in seconds.”

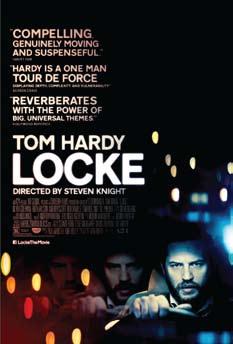

Locke

For this week’s edition of City Paper Arts Club, arts editor Kayla Randall and multimedia editor Will Warren quarantined in a car for an hour and a half with a man named Ivan Locke. He was not having a good night. Locke, which premiered in 2013 at the Venice Film Festival and was released in 2014, is a compelling, experimental film written and directed by Steven Knight and centered on the title character’s car ride to London to be present at the birth of his child. Locke (Tom Hardy) gets into his car at the very start of the film, and he stays there for the film’s entire duration. He’s the only character we ever see. And this film’s experiment pays off in spades.

These Arts Club chat excerpts have been edited and condensed for clarity. For the full chat, subscribe to Washington City Podcast.

Will Warren: It is the story of one man driving to the hospital to see the mother of a child that he has as a result of an affair. He, over the course of this drive, makes 30-something phone calls: [calling] his work, who is upset because he will be unable to do his [concrete] pouring duties, calling the mother of his child, who is in labor, and then also calling home, where he admits he had the affair. And that’s the movie.

Kayla Randall: This movie really resonates with me. Living through a pandemic, it’s really interesting — he is isolated in the film. The filmmaker chose to have a character be isolated the whole time. He’s in his car, making calls.

KR: You learn so much about him, and you learn so much about his life and his family, just through him making those phone calls. He and his two sons really love football, and they’re excited for a big match the night the film takes place. Mom’s making sausages, the whole thing. And then he has to tell her, oh, by the way, this woman’s having my baby and I’m driving to go to the birth. It’s horrible, it’s so sad. But on the same night, there’s this huge concrete pour that has to happen and he’s on the phone with coworkers trying to figure that out. Basically, this film is this one man’s life getting blown up in a single night.

WW: We learn that he’s a super control freak, that’s why it’s so interesting [that] his life is unraveling. His whole life is crumbling. There are just so many tiny writing flourishes that tell us who this guy is. For example, his boss is calling to say that he’s going to be fired. He was saying, “I tried to appeal to the higher-ups and said you’d been at the company for 10 years.” And then, Ivan says, “Actually it was just nine years.” Like, he’s just so precise and literal and trying to be in control of every situation. Ivan is definitely a psychopath.

KR: It captures your attention. It’s actually really suspenseful because of the nature of the filmmaking, which is so compelling: Who’s he going to call next? Who’s going to call him? What’s happening? It feels so real. Within the drama are a million other little dramas. On the subject of Ivan being a psychopath — he totally is. But I think that’s why he’s such a compelling character. It’s that kind of psychosis that makes him so good at his job. It’s the only reason his co-worker was like, “OK yeah, I will do all these things for you and make sure your concrete pour goes well.”