5 minute read

Spiritual Connection: A local

Spiritual Connection

The filmmaker behind Kindred Spirits talks about its special story and documenting D.C. history.

Advertisement

By Kayla Randall

@whichkayla Years ago, a painting on a brochure ended up sparking a documentary idea for independent filmmaker Cintia Cabib. The creator of that painting, Hilda Wilkinson Brown, is one of the subjects of her new film, Kindred Spirits: Artists Hilda Wilkinson Brown and Lilian Thomas Burwell. It tells the story of the bond between a Black American aunt and niece who endured the extraordinary hardships of their eras—the Great Depression and racial segregation—and became artists and educators in D.C. Howard University’s WHUT-TV is broadcasting Kindred Spirits on July 16 and 19, and Cabib and another one of the film’s subjects, Lilian Thomas Burwell, will have a virtual conversation in support of the documentary on July 23, hosted by the Charles Sumner School Museum and Archives. Cabib spoke with City Paper about her film and why it’s so important to preserve local history. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

WCP: How did Kindred Spirits come together?

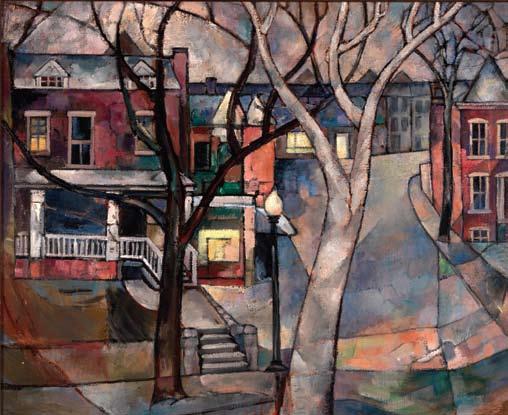

Cintia Cabib: In 2014, I was presenting two other documentaries that I had produced at a conference held by the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. At the conference, there were a lot of tables set up with different historical associations and organizations. On one of the tables, I saw a brochure, and on it I saw this beautiful modernist painting in color of a street scene in Washington, D.C. It was called “Third and Rhode Island” and the artist was Hilda Wilkinson Brown. I had never heard of her before, and I was really struck by that painting. I wanted to find out more about her. In doing my research, I found that she had a niece, whose name was Lilian Thomas Burwell, and I found her contact information.

Lilian was living in Highland Beach, Maryland, so I sent her an email, and I told her I wanted to learn more about her aunt’s work. She was thrilled to hear from me because it turned out that her aunt had played a really influential role in her life. She told me that they were really close, that because of her aunt, her parents agreed that Lilian could study art to become an art educator like her aunt and pursue her art that way. I learned that Lilian had become a very accomplished artist herself. After my initial idea about maybe producing a documentary about her aunt, I decided to produce a documentary about both of them, their really close relationship.

WCP: How big of a part does D.C. play in the story of these women and their art?

CC: A huge part. I love exploring the neighborhoods in D.C., and I love learning about D.C. history. A lot of my documentaries have incor

porated D.C. history. Women artists, especially

All images courtesy of Lilian Thomas Burwell Hilda Wilkinson Brown

African American women artists, are very underrepresented, unsung. There are so many artists out there whose stories should be told. I really wanted to bring to light the lives and work and experiences of these two women, the society in which they grew up and excelled despite the fact that they were discriminated against.

Lilian Thomas Burwell As I learned more about the work that Hilda did, the schools that she attended and the schools that she taught in, Lilian being born during the Great Depression, going to Dunbar High School when schools were segregated, I really wanted to provide a historical context for the times during which they lived. I decided that I wanted to weave that into the documentary as well.

Hilda lived for most of her life in LeDroit Park, a historic neighborhood in D.C. where many accomplished African Amerians lived— civil rights activists, artists, authors, elected officials. She drew inspiration for many of her paintings from LeDroit Park. I really want people to discover their artwork, because for me it was a discovery, so I want to share that with other people. A lot of their work is not in the public view. It hasn’t been exhibited widely. A film can do that: It’s there and it preserves it forever.

WCP: Do you think of this film as preserving D.C. history?

CC: Definitely, because I feel like my work as a documentary filmmaker, when I produce these types of documentaries, I am preserving D.C. history. Lilian Burwell, she is now 93. She is the one person who knows the most about her aunt Hilda’s life and work, and can talk about it and can talk about her own life and work as well. If I didn’t do this now, this could be lost, it would be lost. When she is no longer living, who can tell the story? She is the one who can tell that story and the one who can provide access to so much of her artwork. I did tons of archival research: museum collections, university collections, special library collections. But at the same time, Lilian had all these family photos, which I could use, both hers and Hilda’s. The importance of preserving these photos is huge. I was able to access all this material through Lilian, as well as her story. I see that as such an important part of my work, to get these stories out there.

WCP: What is your process as an independent filmmaker trying to tell these stories?

CC: I would say that, for me, the most important thing in terms of being an independent filmmaker is that I have a love and passion for what I do, and I have a lot of curiosity about people and places and history and issues. I’m always looking for good stories. You have to have a drive to do it despite having setbacks, despite nobody asking you to do it. You do face rejection. You have to believe in what you’re doing and pursue it. I’m the type of person who really likes to have a final product at the end. That’s one of the things I like about documentary filmmaking, you do have a final product. The research, all the archival research, I love—just the discoveries that I make, finding those elements and images that I feel will really make the documentary so much more interesting and visual. Even though it’s a lot of work, I love doing all that. You open up a file when you’re at an archival museum and you suddenly find the image that you’re looking for; you didn’t even know it existed. It’s a real education.