KEYNOTE

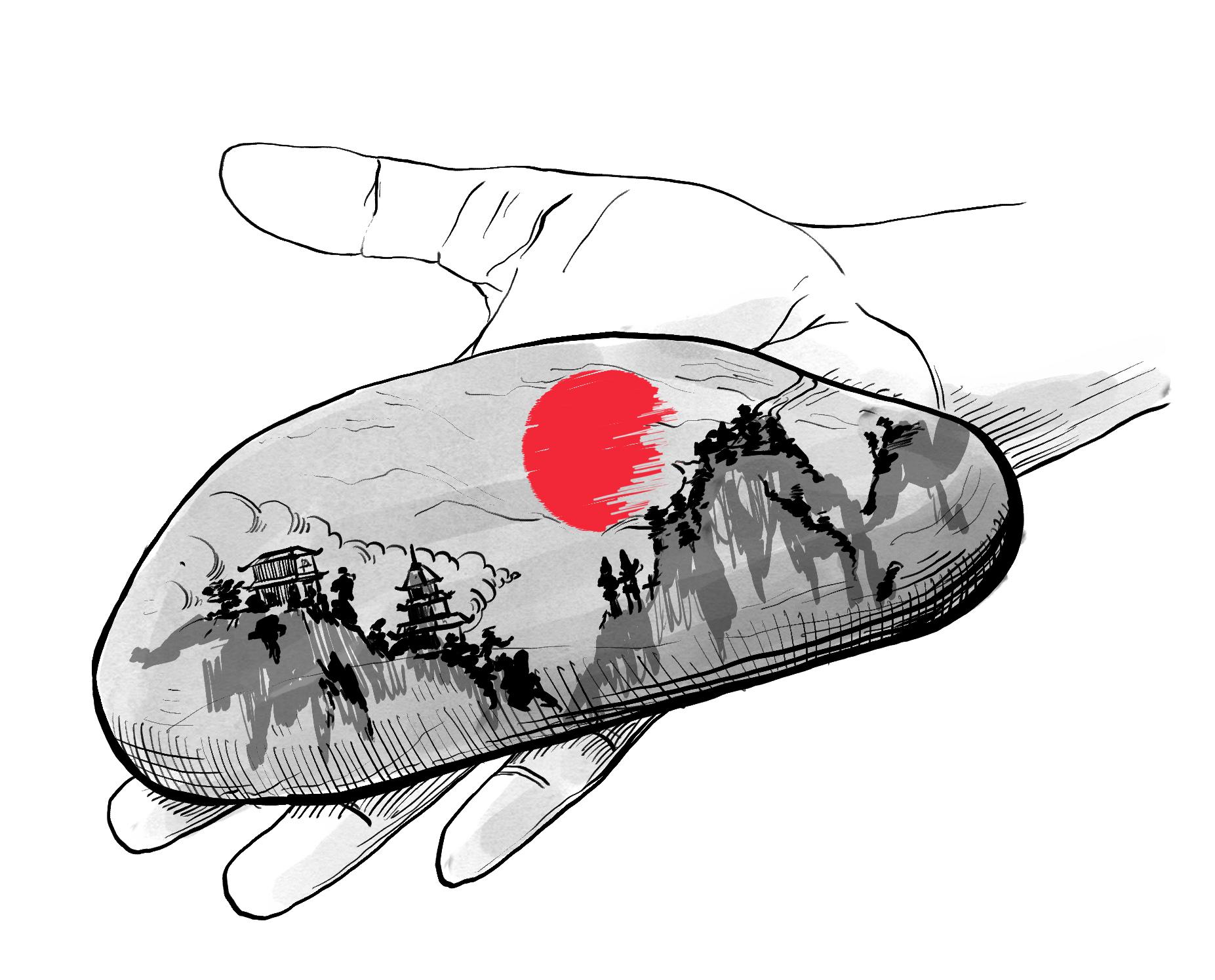

WASSHOI! Interdisciplinary Magazine on Japan

BILINGUAL SHORT STORY WASSHOIMAGAZINE.ORG/MAGAZINE • ISSUE 5, WINTER 2022/23 Yokai! The Foreign Father of

ARTICLE REVIEW Ōmameda Towako and Her Three Ex-Husbands

Japan’s Pre-War Parliamentary Diplomacy

Japanese Ceramics

Arita or Seto Ware?

Luigi Zeni

Japan’s Pre-War Parliamentary Diplomacy and the IPU

Kaori Itoh

(Transl. Amelia Lipko)

Negotiating Modernity Underwater: Women of the Sea in a Changing World Part I

Shuhei Tashiro

In Search of the Truth(?): The Kubotas’ Illustrated Report on the First Sino–Japanese War

Arend Bucher

POPULAR CULTURE / REVIEW

Ōmameda Towako and Her Three Ex-Husbands 大豆田永久子と三人の元夫

Fengyu Wang

FILM

BILINGUAL / REVIEW

Equilibri affettivi e spirituali in Under the Stars di Tatsushi Ōmori

Ilaria Malyguine in collaboration with Nippon Connection

Emotional and Spiritual Balance in Under the Stars by Tatsushi Ōmori

(Transl. Luigi Zeni)

ESSAY TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 6 22 54 34 4 POLITICS ANTHROPOLOGY

EDITORIAL

ARTS

HISTORY

HISTORY HISTORY / POPULAR CULTURE 48 FILM

/ KEYNOTE

Transportation and the Castle Town in the Mōri Clan Domain under Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Hiroki Nakahara (Transl. Amelia Lipko)

ARTS

The Foreign Father of Japanese Ceramics: A Walk Through Gottfried Wagener’s Appointment as a ‘Hired Foreigner’ in Japan

Laura Vermeulen

POPULAR CULTURE

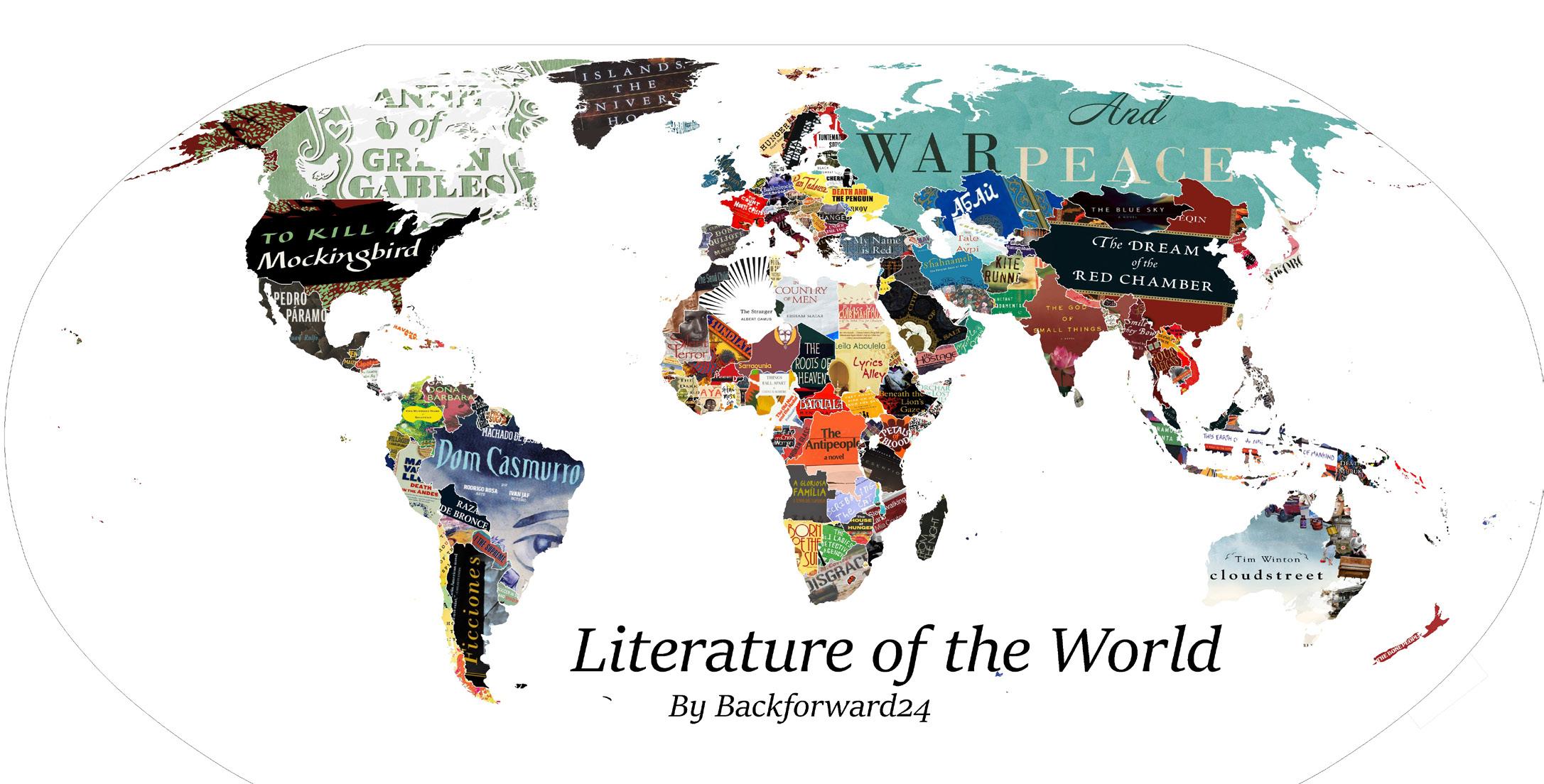

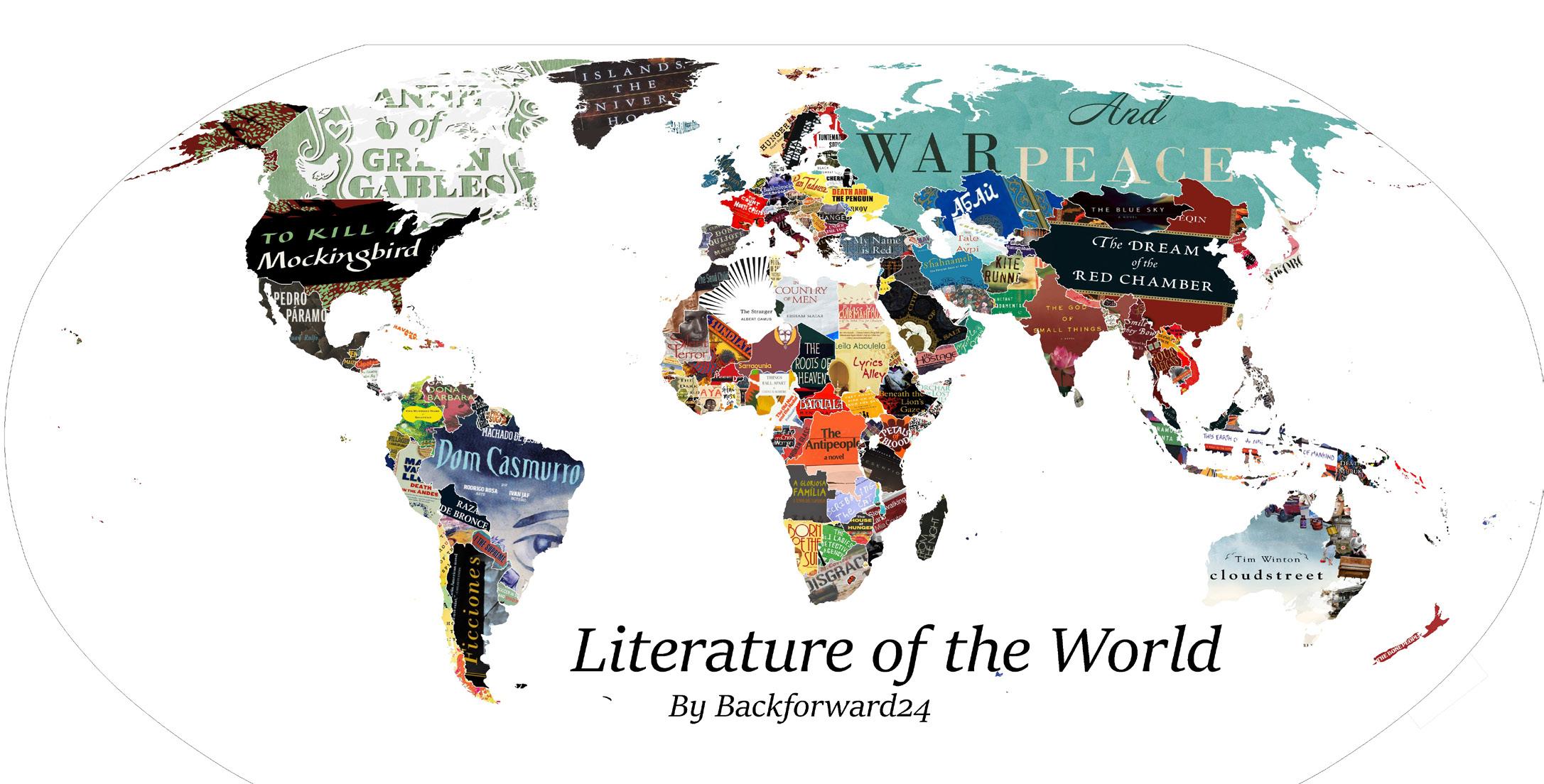

World Literature from Left to Right: Bilingual Authors and Their Influence on Japanese Language

Sara Odri in collaboration with Kotodama

MUSIC

ARTS / POPULAR CULTURE / ESSAY

In The Land of All Things Heavy: The Underground Doom and Sludge Metal Scene in Japan

Patrick Pozzi

SHORT STORY

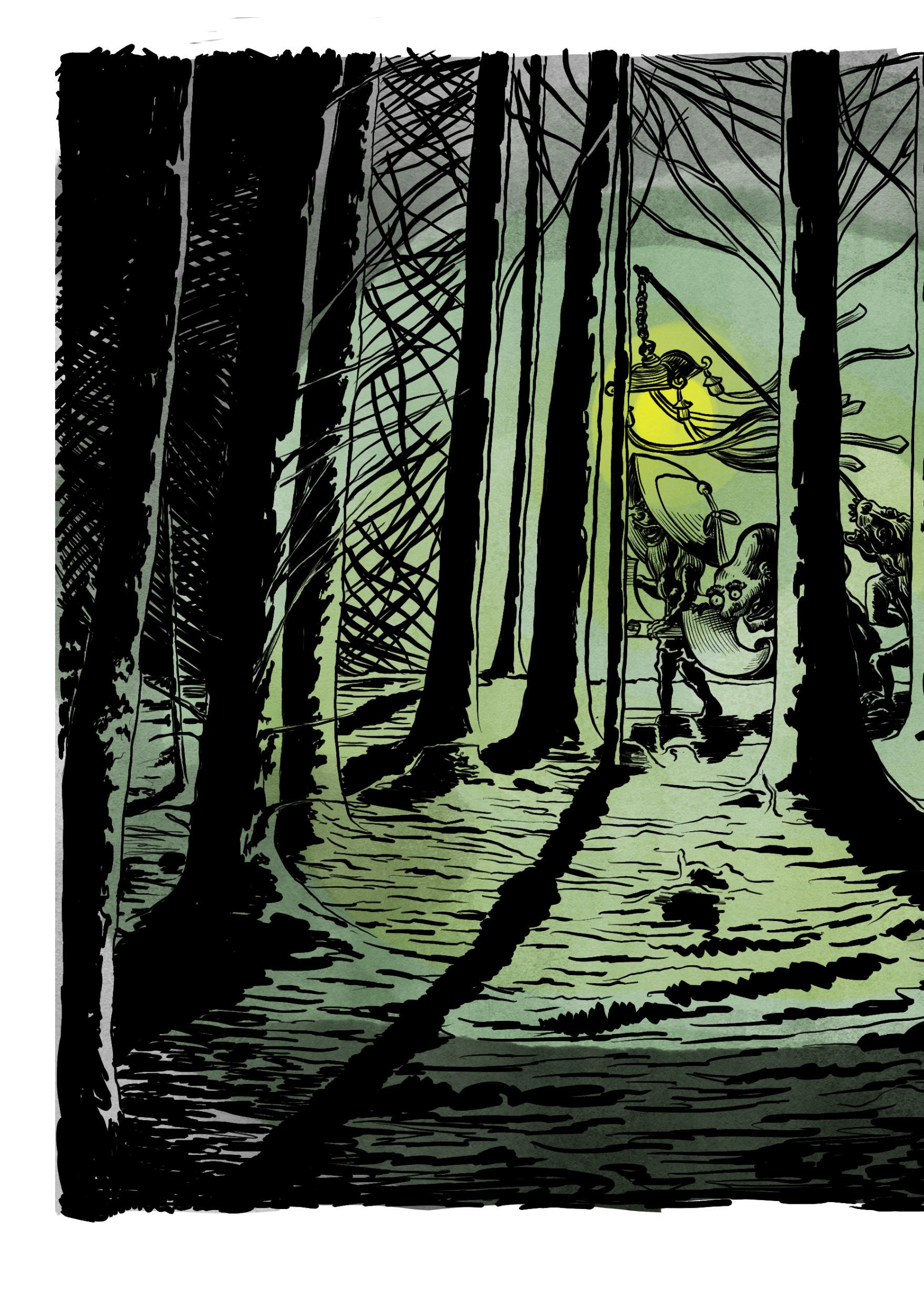

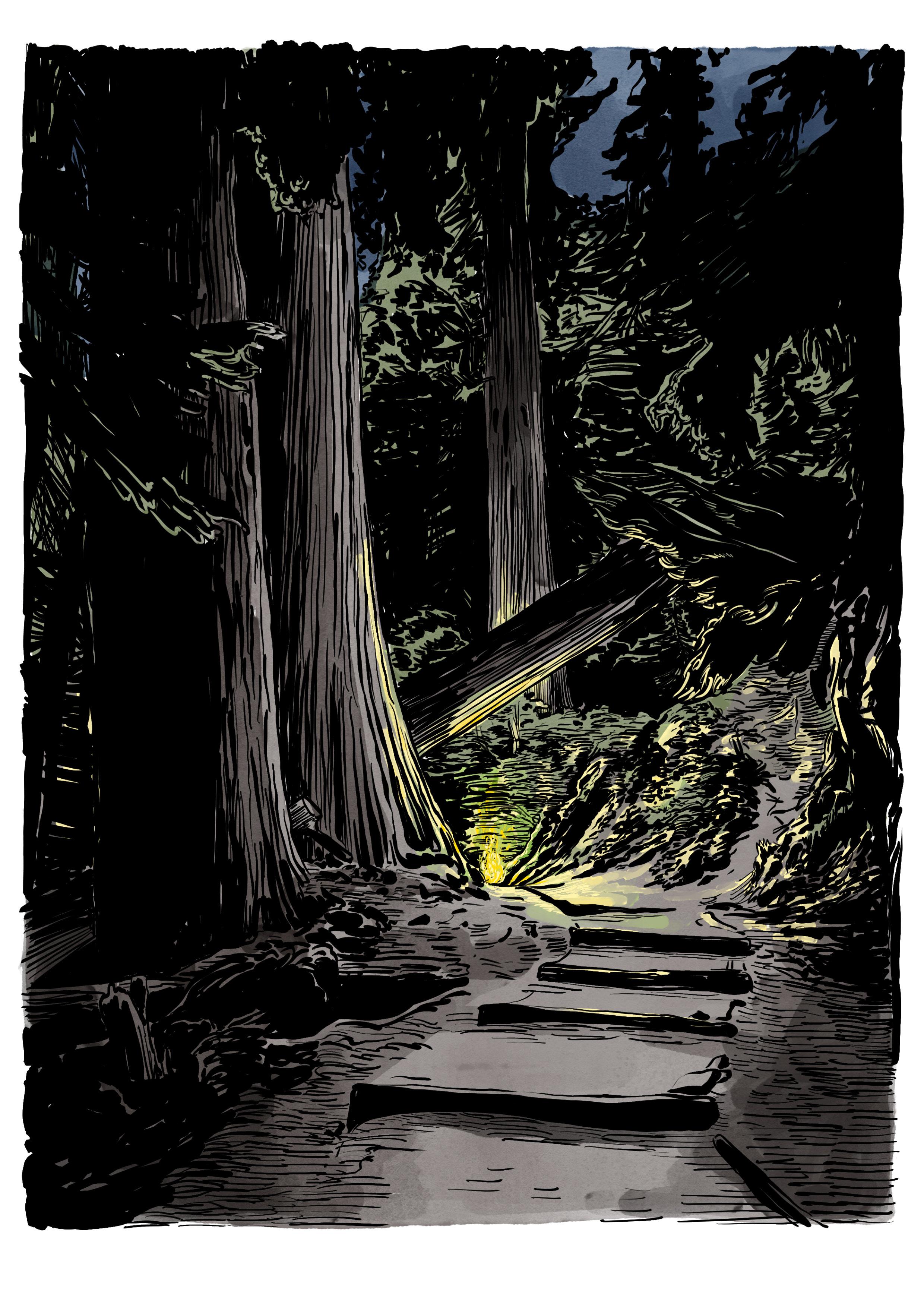

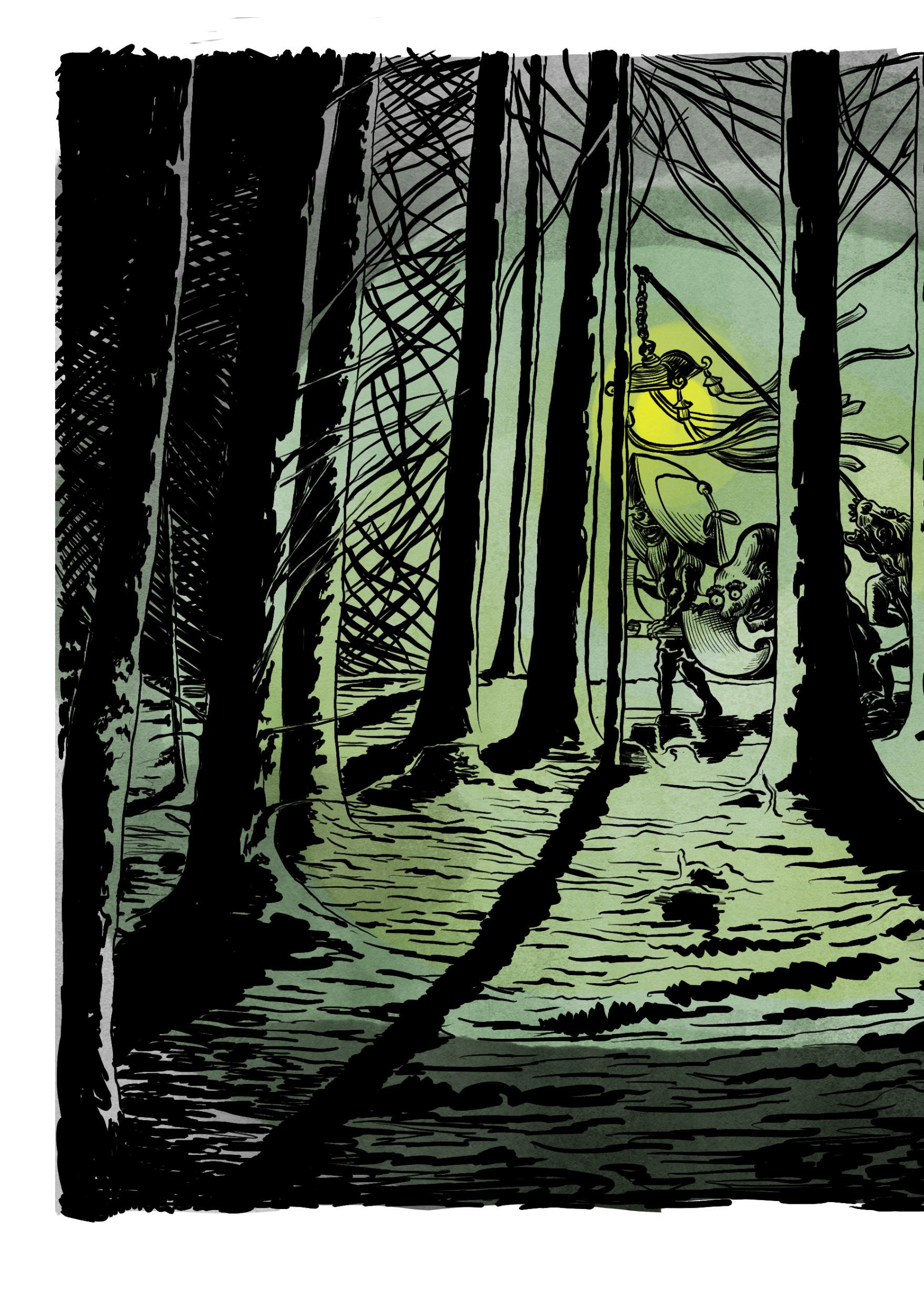

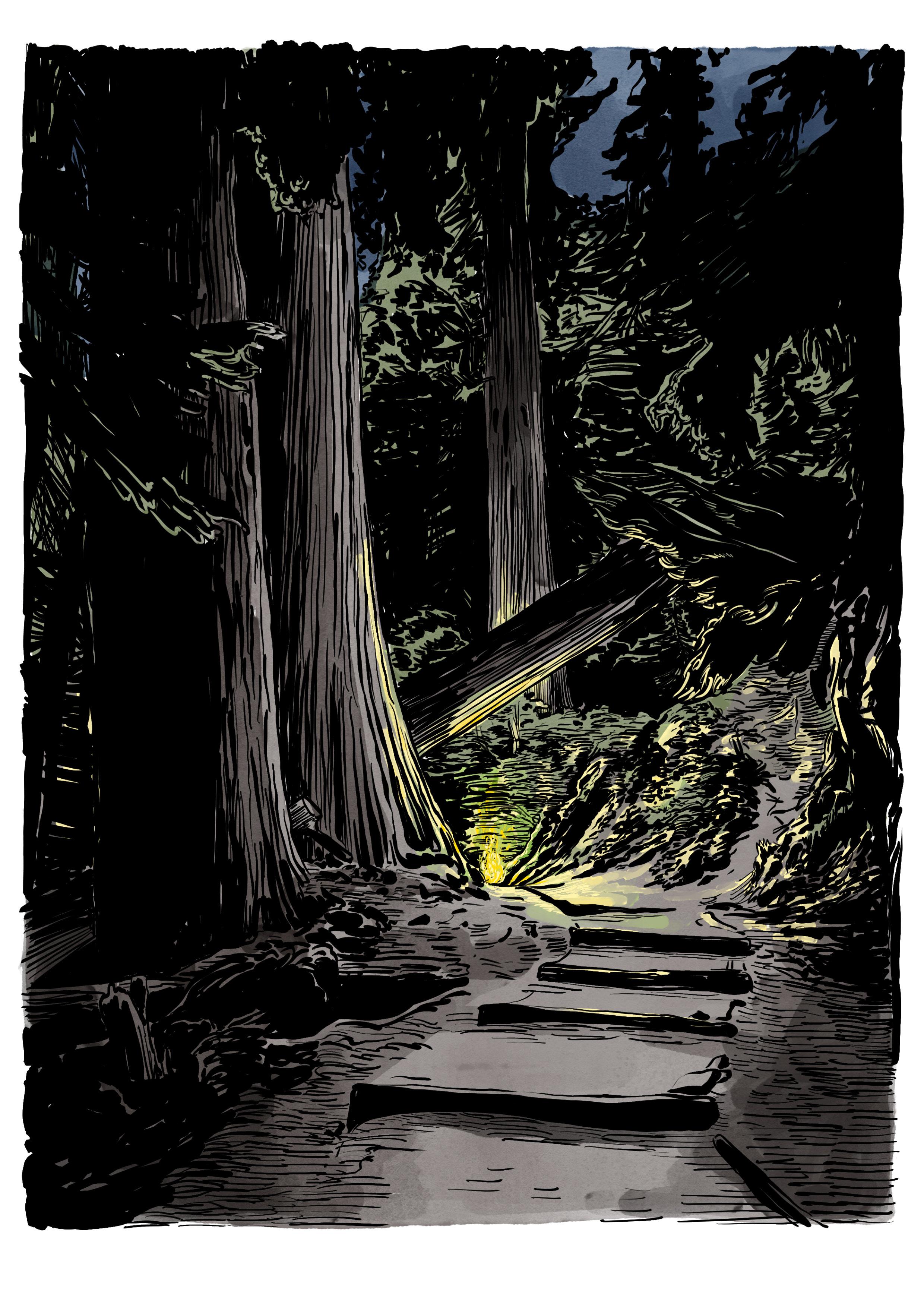

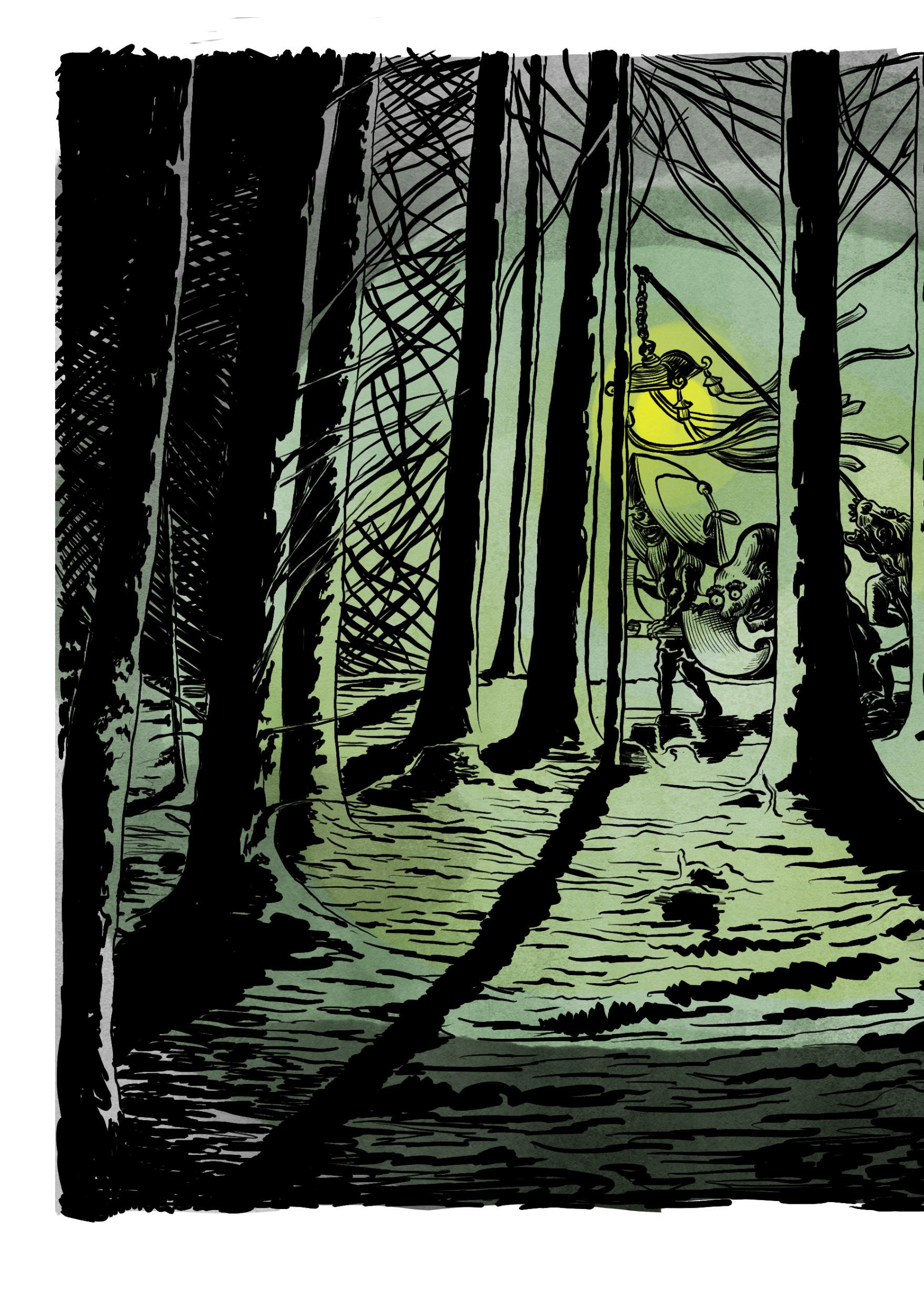

Yokai! (French / English)

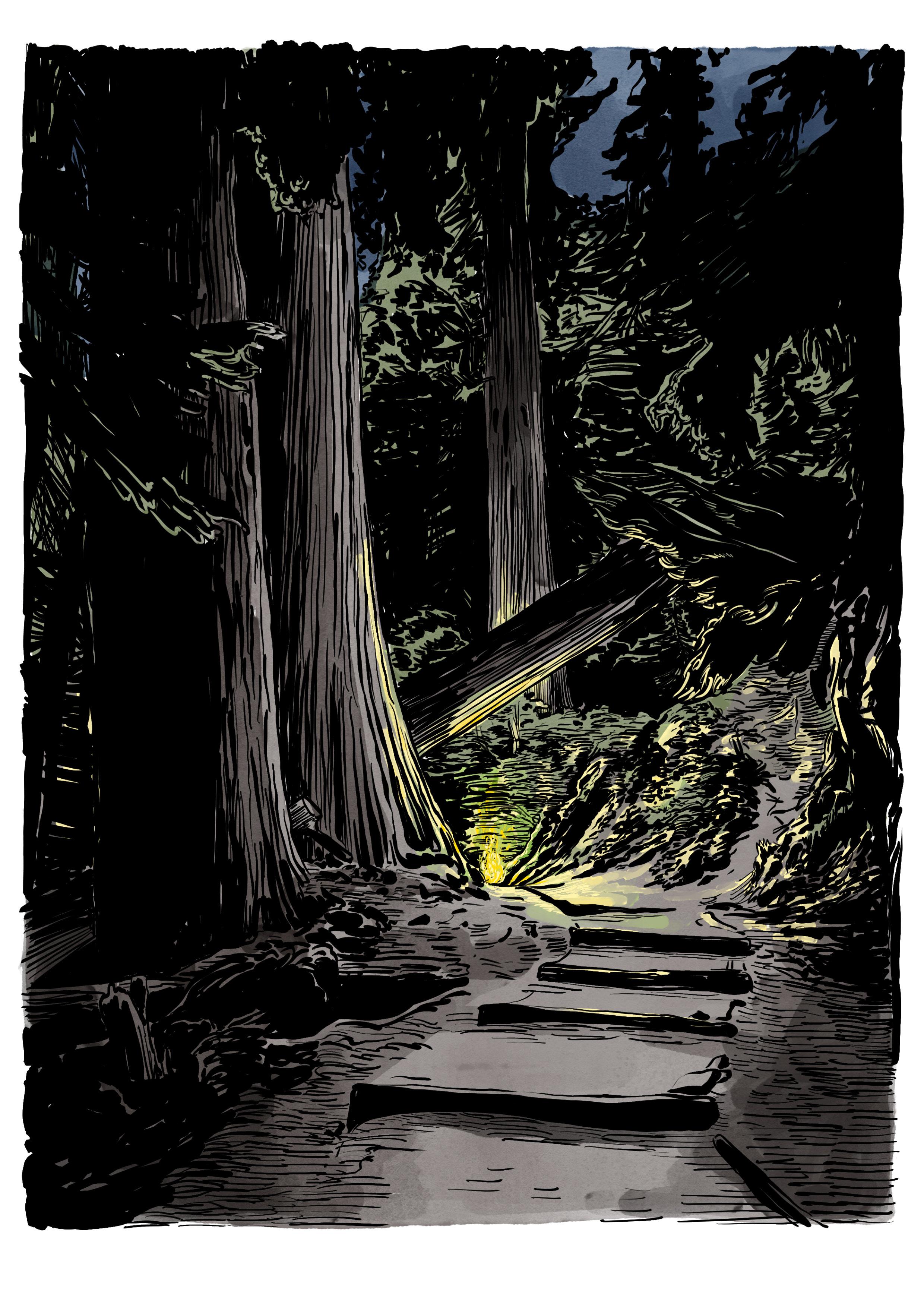

Marty Borsotti Illustrator: Enrico Bachmann

62 68 80 90 98 HISTORY HISTORY

BILINGUAL LITERATURE

Another year has passed and much has changed. Two years of tremors have marked the life of our magazine; born amidst a global pandemic, it was barely one year old when a war broke in Europe. News fatigue, political instability and much more have numbed many people’s hearts. Despite all this, we keep shouting to the world: ‘Wasshoi! Wasshoi!’ and have already reached our 5 th edition. We will fondly remember the past year, 2022, for two main achievements: the publication of our first thematic issue, on Love in Japan , and the acquisition of an ISSN identification (2813-3617), a cornerstone in the building of our project. The chorus of Wasshoi! is getting louder, as many young and talented enthusiasts have joined our group. The issue you are about to read was made possible through their passion and hard work!

Dr. Kaori Itoh, assistant professor at Hiroshima University, does us the honour of starting this new issue with a piece dedicated to Japan’s pre-war parliamentary diplomacy. Shuei Tashiro follows with a chronicle of an attempt to export Japanese ama divers to colonise Korean territories in the late 19 th century, and the tensions that arose as a consequence. Moving on, through the work of Kubota Beisen and his sons, Arend Bucher explores how illustrated prints were employed as a journalistic medium during the coverage of the first Sino-Japanese war. Fengyu Wang then reviews the TV series ‘Omameda Towako and Her Three Ex-husbands’, a tragicomedy about the bizarre everyday life of Omameda Towako, who slowly reconnects with her three (!) former husbands. Ilaria Malyguine, in collaboration with Nippon Connection,

EDITORIAL

4

Aurel Baele, Luigi Zeni, Marty Borsotti

follows with a bilingual review of the movie ‘Under the Stars’, adapted from the novel ‘Hoshi no ko’, which narrates the hardships faced by a young girl born into a family deeply involved in a religious cult. In his article, Hiroki Nakahara takes us further back in time, introducing the history of Hiroshima and its castle, a topic brought from his PhD research. Next comes Laura Vermeulen, who provides us with her case study of Gottfried Wagener, a lifelong hired foreigner who became a central figure in the development of modern Japanese ceramics making. We are pleased to continue our collaboration with the Italian magazine Kotodama with an article provided by Sara Odri, where she delves into the complex and interesting world of Japanese bilingual authors and their relationship with the Japanese language. Patrick Pozzi will

bring us onto a whole new with an essay on the Japanese underground doom and sludge metal scene, showcasing a selection of bands that will help us better understand this subgenre and the uniqueness of the Japanese artists involved. Finally, Marty Borsotti concludes this issue with a short story inspired by Japanese folkloric ghost tales.

Thus, we have nothing more to say than to wish you pleasant reading, and by now you know the drill, right?

Wasshoi! Wasshoi!

5

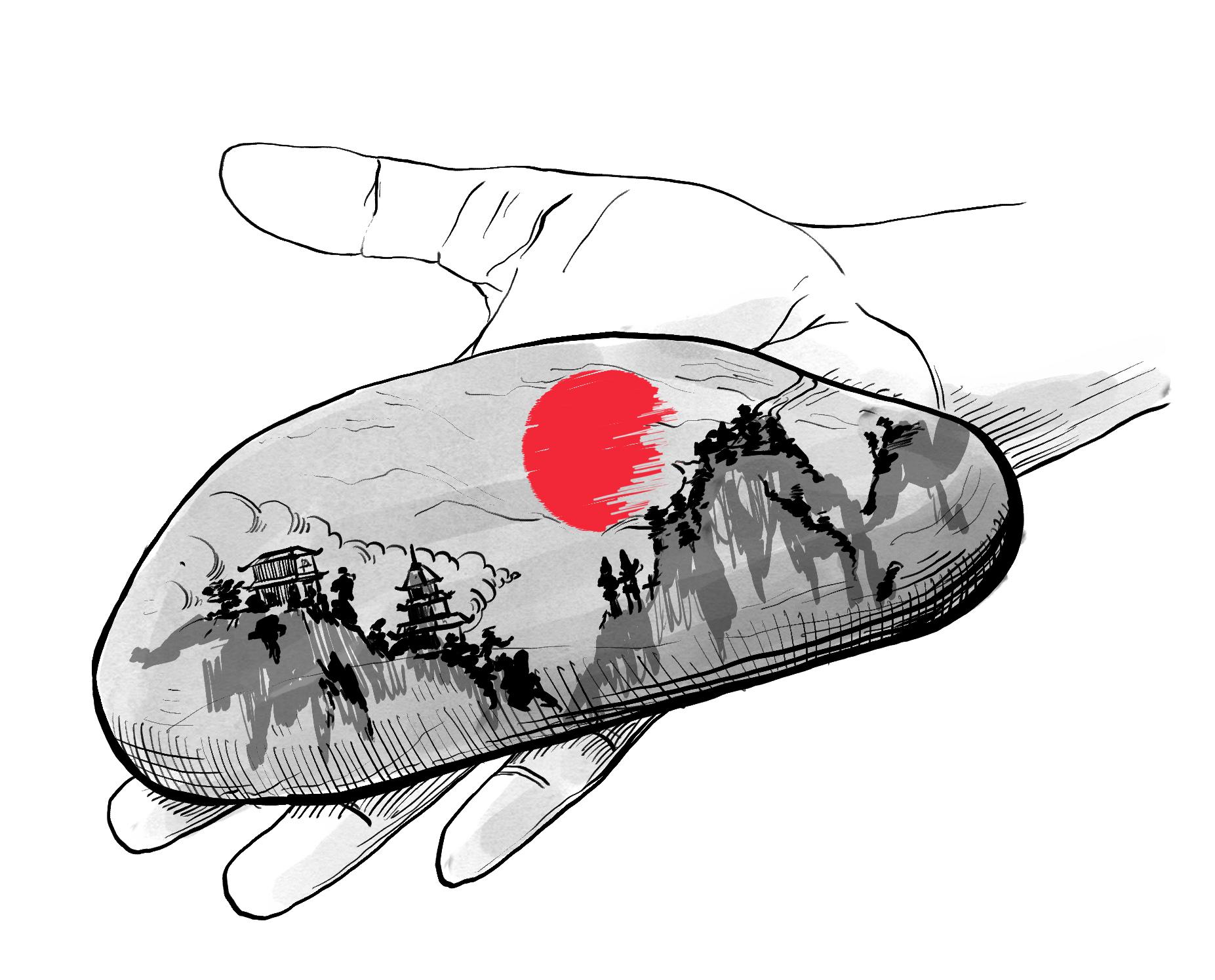

ARITA OR SETO WARE?

Luigi Zeni

Some of you might have recognised the style of the ceramic tea kettles on the cover page: the distinctive blue and white porcelain, reminiscent of Arita ware, produced in northwest Kyushu. Arita ware is typically associated with export ceramics, imported extensively into Europe from the second half of the 17 th century via the Dutch outpost in Nagasaki.

However, these particular tea kettles were produced in Seto city, far from the town of Arita! Seto lies in Aichi prefecture, close to Nagoya, and is another important ceramic centre in Japan – no less than one of the Six Ancient Kilns ( rokkoyō 六古窯 ). As a matter of fact, a revival in the production of porcelain ware took place in Seto at the turn of the 18 th century, after the ceramist Tamikichi Katō ( 加 藤民吉 ; 1772–1824) went to Arita to learn manufacturing techniques and glazing methods, such as underglaze blue cobalt decoration. Following his return to Seto in 1807, his endeavours in renewing the porcelain industry were praised to the extent that a shrine was dedicated to him in the same city with the name Kamagami shrine ( kamagami 窯神 literally means ‘god of kilns’).

Ceramic enthusiasts will discover more to enjoy in this issue of Wasshoi! . The cover image fits well with one article, written by Laura Vermeulen, which deals with the topic of ceramic industry and manufacturing methods in 19 th century Japan, redefined by Western scientist and technician, Gottfried Wagener.

7 ESSAY

Fig. 1 The exterior of IPU’s current executive office in Geneva.

Fig. 1 The exterior of IPU’s current executive office in Geneva.

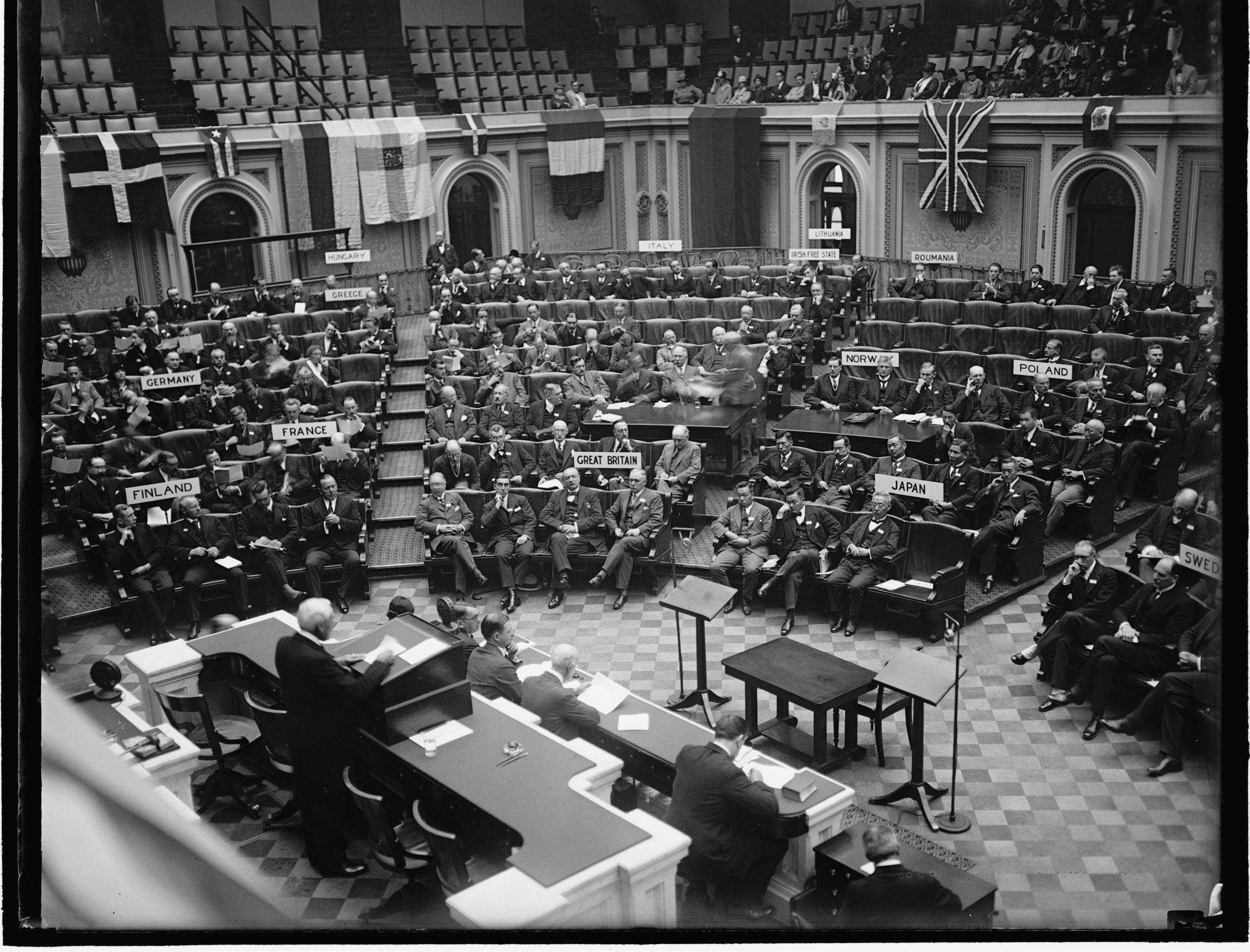

JAPAN’S PRE-WAR PARLIAMENTARY DIPLOMACY AND THE IPU

Kaori Itoh

What is the IPU?

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) is an international organisation with a 130-year-long history that unites parliament members from 178 states. With the aim of fostering common understanding towards international issues in an amicable way, it organises yearly conferences where the participants tackle various problems in a lively debate. While nowadays it is not uncommon for MPs to serve organisations working for the benefit of multiple nations, the IPU can be considered a pioneer for introducing such parliamentary diplomacy (Fig. 1). It was established in 1889, when a Frenchman, Frédéric Passy, and an Englishman, William Randal Cremer, came together to found a salon-like international organisation, gathering together Western legislators who supported the ideal of pacifism. At first, they sought to create a forum for political negotiations. They fervently believed in a movement of internation -

al arbitration as a means to avert war at a time of global political instability, when major world powers were turning against each other, taking part in an arms race that made politicians rack their brains about the increasing military budgets. The IPU’s early successes were the contribution to the First Hague Conference in 1889, which came from a proposal by Russian Tsar Nicholas II and, subsequently, the establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 1901. Ever since, the IPU has been spreading the ideals of internationalism and pacifism, providing a platform for discussion about a range of international issues concerning parliamentary systems, demilitarisation, economics, colonialism and other topics.

9 HISTORY / KEYNOTE POLITICS

Membership and Background of the IPU

Japan, or namely its House of Representatives, joined the IPU in 1908, thus becoming its first Asian member state, and has remained a member ever since (Fig. 2). However, not because it supported Passy and Cremer’s belief in pacifism and internationalism – quite the opposite – it was the result of a growing mood of nationalism in Japan at that time. The Russo-Japanese War, which started in 1904, had led to tax increases that made everyday life more difficult, while embellished war reports raised people’s expectations towards favourable peace terms, making them strongly dissatisfied with the conditions of the treaty that was eventually proposed. This discontent resulted in outbreaks of riots in Japanese cities, most notable of which was the Hibiya incendiary incident. These movements,

led by politicians from the opposition party, called for a firm attitude in international matters. They criticised the government’s diplomatic efforts for being monopolised by the Meiji oligarchy and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, contravening article 13 of the Meiji Constitution, which states that the Emperor has supreme authority over diplomacy. Thus, Itō Hirobumi, who drafted the Meiji Constitution, disapproved of the parliament’s participation in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the Empire of Japan and Imperial Ordinance However, even if this meant that, according to the Constitution, parliament should not be able to make a decision over whether to enter the treaty, the aforementioned movement still strongly sought for diplomacy to be based on public sentiment.

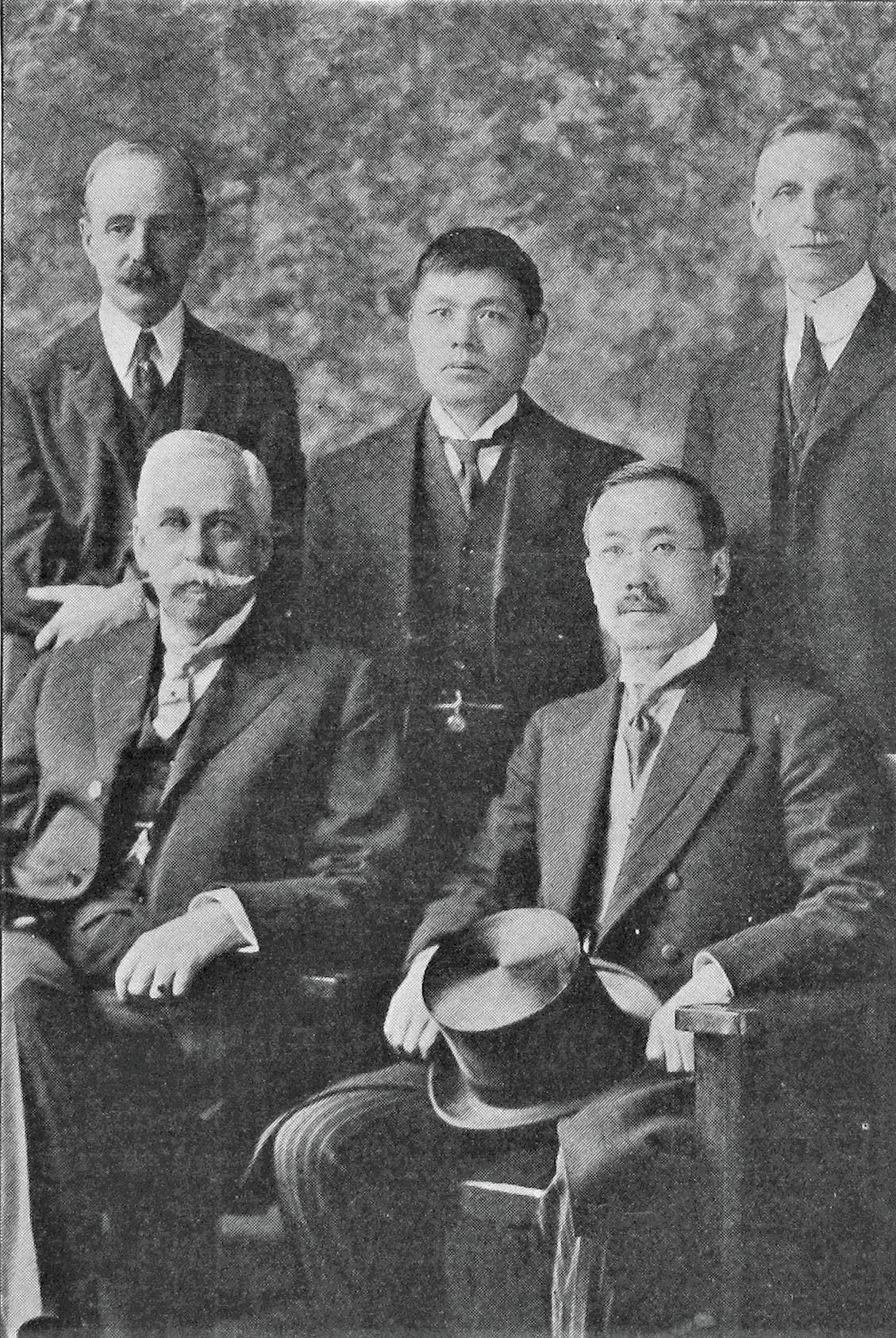

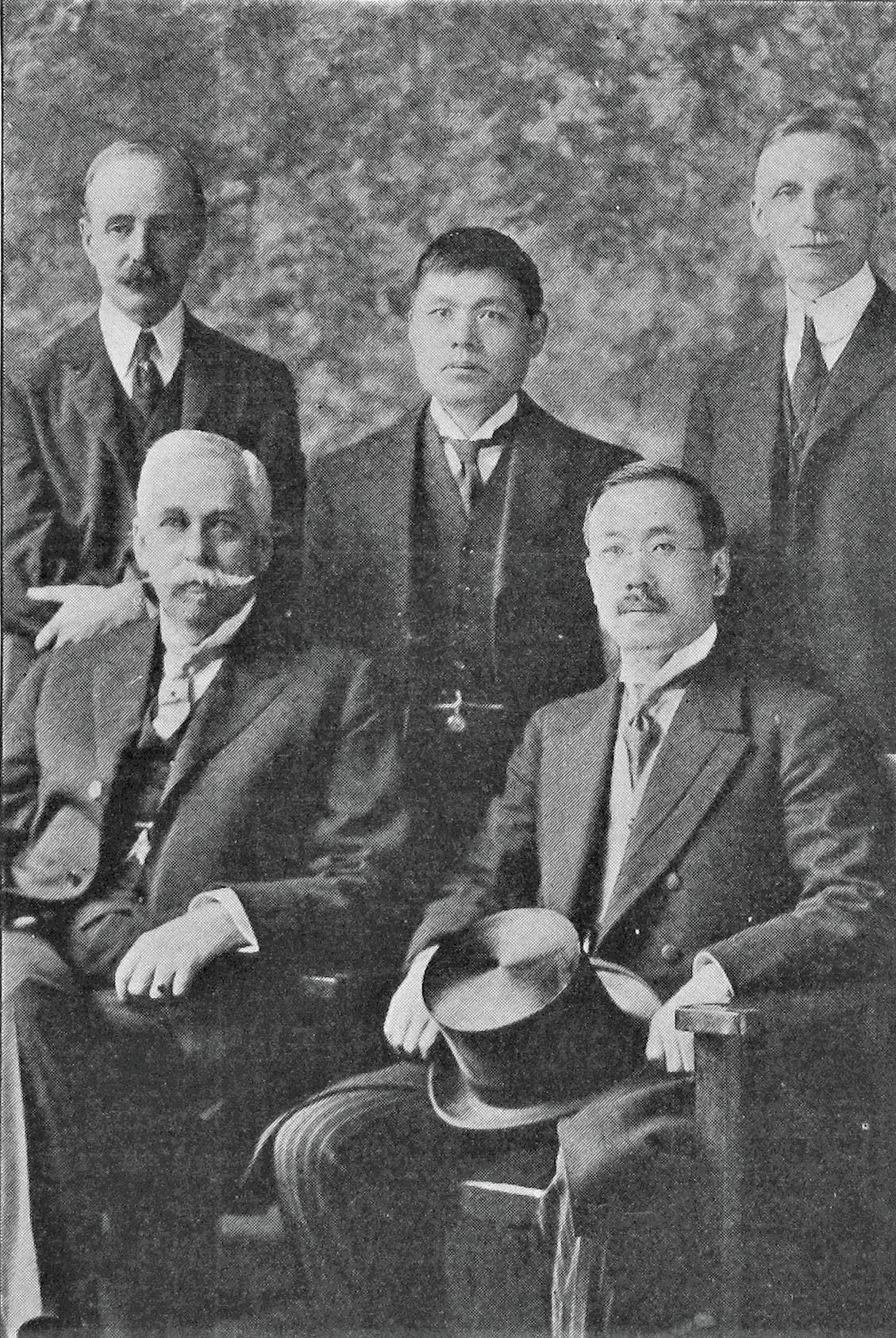

Members of the House of Representatives who held this belief decided to go overseas on behalf of the people in order to personally observe the state of international affairs and use the acquired information as a basis on which they could raise disputes and criticisms at the Imperial Diet assembly. At the beginning of the 20 th century there already existed various means of international travel, such as by ship or by the Trans-Siberian Railway, yet moving from the Far East to the West was not an easy feat, even for politicians. The IPU was able to help such MPs by officially organising their trips abroad and getting them in touch with Western politicians eager for discussion (Fig. 3). One could say that Japan’s parliamentary diplomacy at that time, rather than a means of solving problems, served as a tool

for critics of the government, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in particular, to expand nationalism. Even when the main political groups or individuals responsible for parliamentary diplomacy changed, this basic characteristic, distinctive of pre-war Japan, persisted.

< Fig. 2 Attendees of the 1908 IPU conference in Berlin.

Fig. 3 Delegations from Japan and the US photographed in 1913.

< Fig. 2 Attendees of the 1908 IPU conference in Berlin.

Fig. 3 Delegations from Japan and the US photographed in 1913.

Thus, many of the Japanese MPs who first joined the IPU were nationalists, so their understanding of its founding principles, pacifism and internationalism, was rather poor. The IPU’s secretary general, Christian Lous Lange (Fig. 4), was troubled about its relationship with Japan. After the First World War began in 1914, halting the IPU’s activity, Japan, even though it did not suffer much direct war damage, suspended its relationship with the IPU, which definitively confirmed Lange’s doubts. He desperately tried to keep a neutral stance during WW1 and connect the member states, so he thought it important to find a middleman who would understand the pacifist ideals of

the IPU as well as being well-versed in Japanese internal affairs. That person turned out to be Miyaoka Tsunejirō (Fig. 5), a lawyer from Tokyo and a special correspondent for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which was supporting the IPU economically at the time. Miyaoka was a former diplomat and could tell Lange in detail about Japan’s internal affairs and its political system. He was also able to use his own personal connections to promote appreciation for the IPU among Japanese MPs. Interestingly, this is what he perceived as problematic in the relationship between the IPU and Japan:

There are two points which I would recommend to your attention. First, Japan is young in la vie international[sic]. Secondly, Japan is young in her parliamentary life. Because Japan is old in her history and her civilization many Europeans make mistake in treating her as an old nation. In many ways Japan has juvenile temperament with all its drawbacks as well as its advantages. […] Japan’s parliamentary experience is young. We are just passing through a remarkable period in the constitutional history. Our national parliamentary system is twenty-three years old, but a sort of a system of party government is only just beginning to exist. In this embryo stage of parliamentary experience, parliamentarians naturally change very rapidly. It is only the bureaucrats attached to the Chambers that do not change. The upper House is also stable, but the lower House is continually changing. 1

1 Letter from Miyaoka to Lange, March 17th, 1913 (Box 235, Archives of the IPU, Geneva).

12

As mentioned before, while the House of Representatives (the lower house) belonged to the IPU, the upper house of the Imperial Diet, the House of Peers, did not. Miyaoka points out that because the House of Representatives often holds elections and is dissolved, the MPs switch continuously, making it structurally difficult for a person to develop personal connections with another country, or international organisation, and conduct diplomacy over a longer period of time. Consequently, Miyaoka recommended that Lange persuade the House of Peers to join the IPU, because its term of office was relatively long and it was formed by the

elites including the Kazoku peerage (the hereditary peerage in the Empire of Japan, between 1868-1947), boasting many MPs that were well acquainted with Western customs and had learned foreign languages. Importantly, Miyaoka did not believe that inter-parliamentary diplomacy should be conducted by MPs chosen by the people, but by the aristocracy and the older Establishment – and indeed, the IPU in that period did strongly resemble a salon-like organisation for western nobility.

13

Fig. 4 Christian Lous Lange. Fig. 5 Miyaoka Tsunejiro.

However, the House of Peers did not accept the IPU’s invitation immediately. Although Tokugawa Iesato, who was its president at the time, had a positive outlook on membership, the House of Peers repeatedly rejected the proposition. It is not clear why, but we can suspect it was because of the economic situation following the Russo-Japanese War, doubts about the idealistic pacifism of the IPU, and resentment about the fact that the House of Representa -

tives entered the IPU first. Eventually president Tokugawa and other volunteers from the House of Peers joined the organisation in 1928. As we can see, Japan and the IPU had to overcome many problems connected, among other things, to their opposing beliefs and ideologies, as well as differences in the characteristics of the House of Representatives and the House of Peers, making their relationship not an easy one.

International Activities of Imperial Diet Members during the Interwar Period

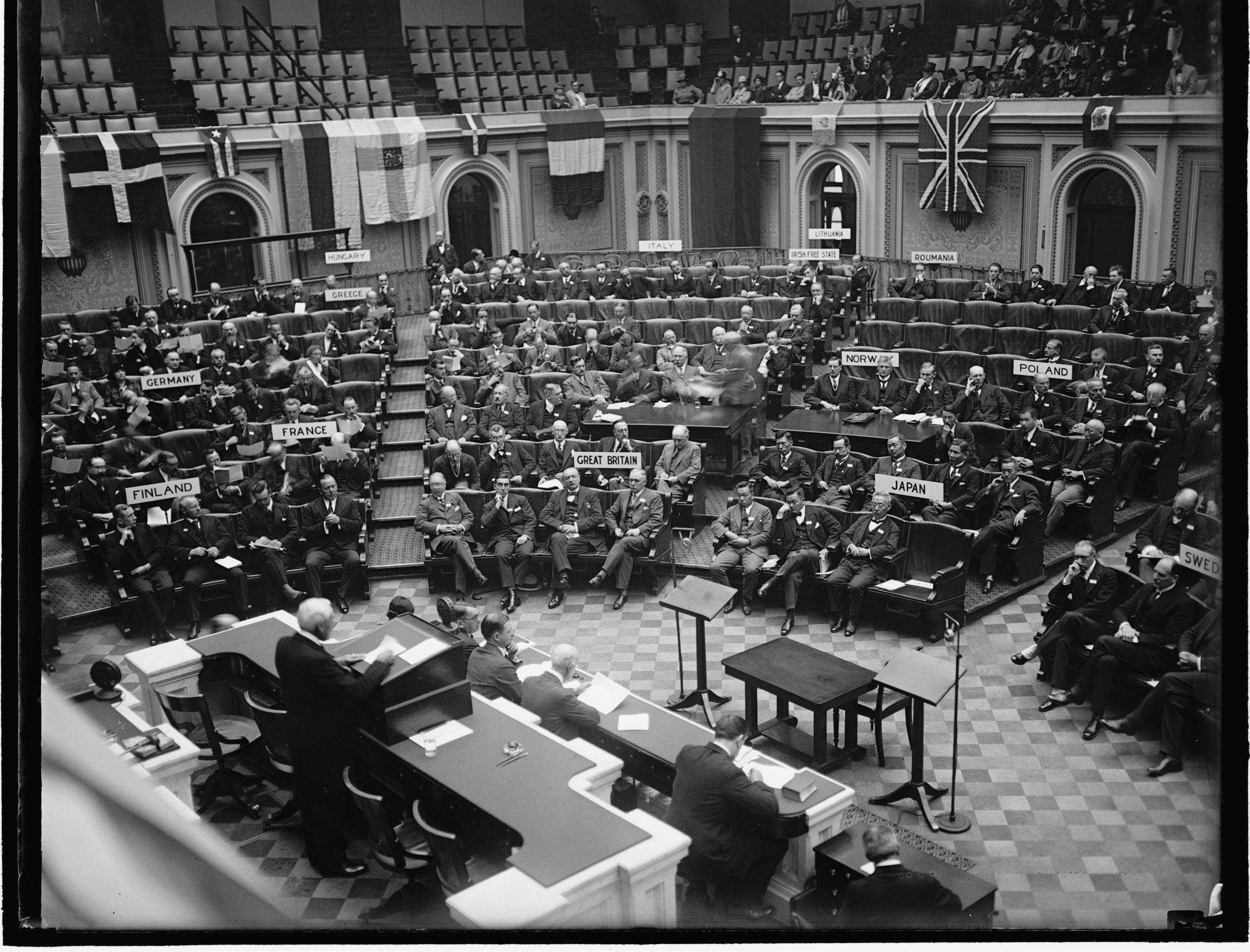

Once the First World War had finished, self-reflection on the fighting led to the creation of many international organisations, with the League of Nations at the core. An era that attached importance to multinational cooperation within various fields began. The IPU transformed as well, detaching from its salon-like western nature and becoming a more global organisation, uniting the parliaments of Eastern Europe, South America and the Middle East. Japan, namely the House of Representatives, returned to the IPU in 1921 to once again delegate multiple MPs abroad. The IPU organised a conference once a year in a major city in

one of the member states with the aim of discussing international politics, disarmament, minority issues, and other topics of interest, but the conclusions had no politically binding force. What is more, the members of each delegation came from both ruling and opposition parties, so the opinions and viewpoints of the representatives often differed even within their own groups. This lack of real agency enabled the IPU to keep a distance from the League of Nations, but at the same time weakened its influence on politics and diminished the power of its words. On the other hand, it did allow representatives of various parliaments to speak freely and take

14

an active part in discussions during the conferences. While the Imperial Diet existed (1890–1947), approximately 200 Japanese legislators from both houses participated in the IPU. Although some members of parliament looked at the IPU with scepticism, considering it too uninfluential, there were also many MPs who felt it significant in the era of internationalism to maintain friendly relations with members of other parliaments, understanding how important it was to guide international politics by putting together various points of view (Fig. 6).

15

Fig. 6 A look at the 1925 IPU conference in Washington.

Some Japanese MPs started forming friendships with foreign legislators, using them as a foundation for their own activities abroad. A member of the House of Representatives from Kagoshima Prefecture, Nakamura Kaju (Fig. 7), graduated from New York University and then lived in the US for many years; he worked as a journalist for the

Japanese-American Commercial Weekly newspaper before being elected to the house in 1924. The following year, he was delegated to participate in the IPU conference organised in Washington and Ottawa. Nakamura expressed his appreciation for and expectations of the IPU in the general debate during his first conference:

It is true to say that democracy is the growing tendency of the world. In such an age, international affairs are no longer the monopoly of foreign offices and trained diplomats. Along with the development of democratic ideas in international matters, modern methods and devices of communication are exercising a potent influence upon the peoples of the world. But a century, even fifty years ago, diplomacy was carried on quietly and often secretly between courts or governments and through accredited ambassadors or ministers. Today with the aid of parliaments and public meetings, of daily newspapers and the freedom of speech, of cable and radio, the peoples of different countries speak directly to each other. In such an age, peace among nations depends not merely upon the attitudes of governments and diplomats, but upon the mental state of the peoples. Democracy, therefore, imposes upon the people a great responsibility not merely in domestic politics, but also in the domain of international relations. We feel therefore that it is incumbent upon the Inter-parliamentary Union to make valuable contributions through its members, who are direct representatives of the peoples concerned, to the erection of the temple of international peace upon the solid foundation of democracy. 2

16

2 UNION

INTERPARLEMENTAIRE

COMPTE RENDU DE LA XXIIIe CONFÉRENCE, 1925, p.585 (Box2, Archives of the IPU).

The above speech encourages the development of ‘democratic’ diplomacy based on the public sentiment of the citizens, which connects fundamentally with the ideology of the Japanese MPs who first participated in the IPU. Nevertheless, such a practice was becoming an important means of fostering international understanding and facilitating communication. In other words, Nakamura’s ‘democratic diplomacy was not a simple derivation of nationalism, but served to promote internationalism: to inspire in people an active interest not only in domestic matters, but also in international ones.

Nakamura decided at this point that he should be politically active abroad. He participated in the pre-war IPU conferences and became more closely affiliated with them than any other member of the House of Representatives, forming relations with MPs from many countries. He paid much attention to international issues and was particularly concerned about the unresolved problem of Japanese emigration to the US, which remained a grave matter es -

pecially during this period. He investigated the actual living conditions of Japanese emigrants in North and South America and tried to educate his compatriots on the hardships that they faced through a self-published magazine, at the same time fiercely criticising the government’s migration policies at the Imperial Diet assemblies. This gained him the nickname ‘internationalist ’and passionate support, especially among Japanese immigrants.

17

Fig. 7 Nakamura Kaju.

Disturbances in Internationalist Collaboration and Japan’s Parliamentarianism

As is commonly known, Europe in the 1930s experienced a drastic breakdown in internationalist collaboration due in part to the rise of fascism. The situation in Asia was strained as well, with international tensions involving mainland China, especially after the Manchurian Incident of 1931, and in 1933 Japan announced its withdrawal from the League of Nations. The question of how to rebuild international relations after this declaration became a huge issue. The IPU, too, discussed how to handle Japan’s South Pacific Mandate. Before the 1935 Madrid conference, a committee gathered and drafted a resolution to deny Japan the continuation of the mandate. When the first tidings of this submission arrived in Japan, some claimed that they should leave the IPU if the resolution were to be adopted. Italy had temporarily withdrawn from the organisation in the previous year, so it was a possibility for Japan as well. However, the Japanese delegation con -

ferred with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other related authorities, and decided to appeal to the other delegations to abandon the resolution before it could be brought up for discussion. Even if it were to be implemented, they nonetheless decided not to leave the IPU. By no means did the Japanese delegation make light of the influence that the IPU’s decisions had on international opinion; on the contrary, they decided to use the IPU as a chance to foster understanding for Japan’s viewpoint from other countries. 3 Unexpectedly, their withdrawal from the League of Nations led Japan to exchange opinions on the international arena of the IPU, acknowledging it as a platform for making their claims known to others. Furthermore, the mandate resolution was successfully abandoned thanks to the workings of Nakamura Kaju and colleagues, so, the relationship between the IPU and Japan did not suffer any real strain after all.

3 A telegraph from 28th July 1933, number 7570, ‘ Daigishi no dōsen ni kan suru ken ’ ( Bankoku giin dōmei kaigi kankei ikken , volume 2 in possession of Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan), a telegraph from 28th August 1933, number 8277, ‘ Dai 29 kai bankoku giin kaigi shussekisha no dōsen ni kan suru ken ’ (as previously).

18

The speeches of Japanese MPs from the second half of 1930s clearly show how they actively wanted to familiarise the international community with Japan’s standpoint through the IPU. For example, Hatayama Ichirō, who attend -

ed the 1937 Paris conference, stressed in his speech that Japan’s parliamentary system would not waver even if faced with a political crisis with the following words:

It is true that Japan to-day, without exception from other countries, is facing a crisis of a political and economic character. As to the political crisis, at the outset, I can assure the members of the Congress that our parliamentary system will live through the present difficulties. From our point of view the constitution which was promulgated by the Emperor Meiji and by virtue of which was constituted the present parliamentary form of Government has a special position in the mind of the people. Even in the present crisis no one has questioned the principle upon which is built our national life. This conception is of a fundamental character in our political life. 4

MPs who emphasised the robustness of Japan’s parliamentary system in this way often attached importance to cooperation with the United Kingdom and the United States. In other words, this attitude and strong belief in parliamentarianism demonstrates how different Japan’s viewpoint was from the anti-parliamentarians represented in Germany by Nazis burning down the Reichstag. Japanese MPs argued through the IPU that it was an utter misunderstanding to equate the German or Italian political systems to that of Japan. Their efforts to foster a relationship with the United Kingdom and the United

4 UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE COMPTE RENDU DE LA XXIIIe CONFÉRENCE, 1937, p.374 (Box3, Archives of the IPU).

States is further proof of this. A speaker of the lower house, Koyama Shōju, expressed a wish to organise an IPU conference in Tokyo, to invite members of various parliaments so that they could come into contact with the real Japan and form a new opinion of it. 5 This proposition came to nothing because of the outbreak of Second World War, but the idea alone makes it clear that Japan had certain expectations from the IPU.

5 Shōju Koyama addressing the president of IPU, Carton de Wiart, on 26.07.1939. ’ 1940 nen ni rekkoku kaigi dōmei kaisai enki ni kan suru ken ’ in Documents related to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, volume 24 (in possession of Secretariat of the House of Representatives).

19

The IPU and Japan After the War

In 1945, Japan had lost the war and by forfeiting sovereignty it had lost the capability to participate in the IPU. The organisation tried to make it possible and approached Japan about it, but the Japanese firmly held to the resolution that they would only re-join after having reclaimed sovereignty, eventually returning to the IPU in July 1952.

The post-war political measures regulated Japan’s parliamentary system of governance, the main example of which was the establishment of a new constitution. This made the debate about how to conduct diplomacy and organise parliament even more animated than before the war. The methods of Yoshida Shigeru, who had driven the Japanese government’s diplomacy in the second half of 1940s, were criticised by his political opponents, Hatoyama Ichirō and Kishi Nobusuke, as being self-righteous and secretive, as they called for the development of ‘diplomacy led by the citizens’. Once Hatoyama and Kishi gained political power, this idea, advocated before the war by the governments ’critics, started being introduced more and more firmly into government-led diplomacy. This tendency was also made clear in a speech by Ikeda Hayato, who succeeded Kishi right before the first

IPU conference in Tokyo, 1960. Ikeda gave the opening address as prime minister, expressing his wish that the IPU would continue to support the continuous development of ‘diplomacy led by the citizens’.

On the occasion of the Tokyo conference, the relationship between Japan and the IPU became closer than ever before. A central role was played by Fukunaga Kenji, an influential politician who served as Minister of Labour under Ikeda’s administration. Fukunaga became a member of the IPU’s executive committee and lead it to explore such topics as the problem of nuclear disarmament and space law. He also became well acquainted with the Soviet Union’s parliamentary representatives through the IPU and later developed bilateral parliamentary diplomacy between it and Japan: for example, leading the Japanese delegation to the Soviet Union in 1964. Fukunaga’s endeavours supported and complemented Ikeda’s diplomacy, which aimed to suppress the cold war while striving for cooperation and economic collaboration with the United Nations. After this, Fukunaga continued his close relationship with the IPU, which led to the organisation of a second conference in Tokyo in 1974.

20

In this way, the post-war shift in political systems and dynamics internalised ‘diplomacy led by the people’ through government measures. Parliamentary diplomacy with IPU, which in the pre-war period was merely an offshoot of international politics, came to fulfil the role of backchannel diplomacy that complemented government actions. From the second half of the 1960s, bilateral and multilateral parliamentary diplomacy gained momentum outside of the IPU, involving not just ruling parties, but also opposition parties and nonpartisan figures. To this day numerous Japanese members of parliament have come to be active in the field of public relations, conducting diplomacy in various settings.

Suggested Reading

Itoh, Kaori. Giingaikō no seiki: rekkokugikaidōmei to kingendai nihon . Yoshida shoten, 2022.

21

divers) on shore: one, who has just brought up a shellfish, holds a trowel in her teeth as she wrings out her skirt, while the other woman places the shellfish in a basket. Colour woodcut after Utamaro, 1900/1920 (?).

Fig. 1 Two amas (women

Fig. 1 Two amas (women

NEGOTIATING MODERNITY UNDERWATER: WOMEN OF THE SEA IN A CHANGING WORLD

Part I: Colonial Encounters, Intersectional Struggles: A Transnational History

Shuhei Tashiro

Custodians of one of East Asia’s oldest occupations, the ama divers have long built traditional livelihoods by gathering shellfish and seaweed. This tradition, however, seems on the brink of disappearance in Japan today. How have the ama got where they are? What can we learn from them? This article series will trace the historical processes through which the ama’s modes of living and working both in and above the water have been transformed in the face of various, sometimes violent, forces of the emerging modern world. What constitutes the tensions and synergies between national identities, women and men, and humans and other species within and beyond Japan’s borders? First, in this article, we will look into a transnational history of the ama by considering how women divers on both sides of the Korea Strait encountered and negotiated colonial experiences in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

‘On her first visit to her mother’s hometown Kita-Sanriku, Aki encounters her grandmother and discovers she is an ama diver. So begins Aki’s journey to becoming an ama herself…’ Almost ten years have passed since NHK’s 2013 drama series Amachan ( あまちゃん ) swept Japan. To many, this asadora 朝 ドラ (morning drama) provided a fresh, contemporary picture of the lives and struggles of the women divers. But one question seems to remain: are young people choosing to become ama divers like the protagonist Aki?

The ama are professional freedivers who gather shellfish and seaweed for a living. 1 It is one of the oldest existing professions on the archipelago: archaeological evidence suggests that people dove to catch abalones thousands of years ago. The genders of these early divers are unclear – most likely, both men and women dove. In fact, the word ama was used to refer generally to both male and female freedivers.

1 Female ama divers are referred to as 海女 , meaning ‘women of the sea’, as opposed to the male 海士 , though both are pronounced ama . Alternatively, 海人 and 蜑 , both also pronounced ama , have also been

used. Today, female ama make up the majority of ama divers operating in Japan. For this reason, ama in this article refers to female divers equivalent to the Japanese 海女 , unless otherwise specified.

23 HISTORY ANTHROPOLOGY

The Ama: Past and Present

Few ama actively documented their lives in old historical records, but we can trace them through literary appearances. In the Man'yōshū , 2 over 80 waka poems mention the divers, a testament to how popular they were in the imagination of urbanites. Later, Sei Shōnagon suggests that the profession has become a female-centered livelihood ( ama 海女 , literally ‘women of the sea’). In the Makura no Sōshi , 3 she expresses her admiration for the brave woman whose life-risking plunge into the dark, raging sea ‘almost brings her to tears’–while the male collaborator on the boat, likely the woman’s husband, has the easiest job and is ‘indescribably pathetic’.

While this might be too harsh an assessment of the collaborative ama technique known as funado , there is no doubt that ama practices require considerable skill, experience, and audacity. This perilous occupation would go on to become deeply intertwined with the spiritual lives, myths, and folklore of the people on the archipelago. Since the medieval period, the ama of the Shima Peninsula, one of the hotspots among ama villages, began to deepen their ties with the Ise Shrine. They became the primary suppliers of noshi awabi , abalone offerings of special significance to the Shinto tradition. Myriad myths have also developed not just among but about the divers: historians have, for instance, pointed out the ama ’s possible link with the Urashima legend. 4 Many folklorists, ethnologists, and anthropologists have argued for the uniqueness of the ‘ ama culture’, whilst often entwining it with origin myths of the Japanese nation.

This allegedly unique tradition, however, seems on the brink of disappearance. In the mid-20th century, there were more than 20,000 ama divers across Japan. Today, the number has plummeted to about 2,000. This rapid decline has rung an alarm bell: researchers, activists, and the ama themselves are now working hard to gain UNESCO cultural heritage recognition. Part of the impetus has been to follow the Korean divers on Jeju Island, who won such recognition in 2016 and with whom Japanese ama share a history of colonial migration. Here, is it possible to understand ama divers not just in terms of their distinctiveness but through their connections with the world beyond Japan? How did Korean divers negotiate rising tensions in Japan? Might this shared history of transnational migration help us formulate new questions–and answers–to our collective task of crafting a more relational world today?

2 Man'yōshū 万葉集 is an eighth-century collection of Japanese poems ( waka 和歌 ).

3 Makura no Sōshi 枕草子 , or The Pillow Book , is a book of essays, observations, and poems written by Sei Shōnagon 清少納言 in the late tenth and early eleventh century.

4 This is one of the most widely-known Japanese fairy tales in which the protagonist, Urashima Tarō 浦島太 郎 , rescues a sea turtle on a beach and is, as a reward, taken to an undersea palace ( Ryūgū-jō 竜宮城 ).

24

Ama Divers in Korea: Colonial Ambitions, Troubled Encounters

To understand how the ama ended up in Korea, we need first to consider the historical landscape of Meiji Japan (1868–1912). Stories of modern Korea-Japan relations often begin with Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910. This is because this date marks the beginning of Japan’s fully-fledged imperialism, or in other words, military expansion on land. This historical narrative, however, overlooks an important form of modern expansionism that not only came prior to 1910, but took on modes of colonial expansion other than military or terrestrial. It happened at sea–as part of the fishing industry.

In the mid-Meiji era, fishermen and ama divers across Japan were faced

with increasing problems. In the 1880s, coastal ecosystems in western Japan suffered from denudation, a form of undersea desertification leading to the decline of seaweed. At the same time, the demand for valuable seaweed such as tengusa (a key ingredient of tokoroten , or Japanese jelly noodles) soared, resulting in over-harvesting. In response to these changes, the Meiji government made it state policy to expand its fishery operations to Korea (known as Chōsen-shutsuryō 朝鮮出漁 ) under an unequal treaty. Working closely with commercial capitalists, the nascent empire sought to make big money in neighbouring waters through organised migration.

25

Fig. 2 Left, a naked female diver hands an awabi shell to a man and a boy waiting in a boat; right, three men with deformities sit around a fire. Woodcut attributed to Jūsui, 1789.

Now, these fishery owners hired skilled divers and coordinated batches of hundreds of ama before crossing the Korean Strait. For the ama , going overseas must have brought about anxieties; but at the same time, the abundant resources in Korean waters promised a fortune. Bright futures awaited the divers, who dreamed no less than their employers of returning home one day with rosy fame and wealth.

The ama were now part of a dangerously invasive colonial enterprise. On Jeju Island, known to be one of the few places outside Japan where women operated as occupational freedivers, the Japanese and Koreans clashed frequently. Strong tensions arose due to the Japanese scuba divers, who used technical equipment to catch and extirpate most of the local marine fauna in the decade leading up to the ama ’s freediving operations. In 1891, fishermen from Jeju Island organised riots against the Japanese divers, which resulted in several locals being killed. The Korean residents stood up in protest and fury, but the Japanese summoned imperial naval ships to intimidate and subdue them. Force ensured profits.

Such violent encounters were also linked to cultural clashes. For instance, the locals and Japanese ama divers differed in the way they dressed and behaved. The Korean islanders, who followed Confucian morals, covered their skin, adhered strictly to age hierarchies, and separated female and male spaces. In contrast, the Japanese divers dove virtually naked (for practical purposes) and broke the gender code on the island. This led the locals to develop much contempt toward the invaders. The latter, in turn, looked down on the Jeju divers for their low technological standards (e.g., the absence of underwater goggles), justifying their own presence. Friction persisted over time, so much so that most ama lived and slept on their ships for fear of attacks by the locals.

Colonial fisheries continued after the 1910 annexation. These few decades set off a series of transformations on both sides. On the Korean end, there came a surge of women divers. According to some anthropologists, the women divers of Jeju Island had only harvested seaweed as a fertilizer for on-land farming prior to the Japanese

26

invasion. The colonial encounter, however, opened up a fully-fledged fishing industry that exported vast hauls* to Japan and the wider world. More and more women, in turn, took advantage of this emerging economic niche.

Similarly, the Chōsen-shutsuryō changed myriad aspects of Japanese ama operations such as an increasingly capitalist contract system, but above all, the question remains as to the degree to which the divers were complicit in the expansionist enterprise. Certainly, they served as important actors in the invasive venture whose benefits sponsored later imperialist aggression. Things become rather complex, however, especially when considering the fol -

lowing: the ama were themselves subject to monetary exploitation by their employers, who underpaid the divers for their own profits. Here, one point seems clear. Their migratory labour across Korean waters marked the beginning of an essentially modern era: to dive now meant to be part of a transnational network of social, economic, and political forces far beyond the confines of their local shores. This modernity travelled in both directions.

27

Fig. 3 A Japanese diver in the white diving suit that became widely used after migrations to Korea and until wetsuits were adopted in the 1950s and 1960s.

Chamsu Divers in Japan: Precarious Labour, Intersectional Struggles

How did the Korean divers experience these rapidly changing tides? Jeju Island is known to have been the only place in Korea where women played an important role in occupational freediving (originally called chamsu 잠수 ) prior to the Japanese invasion. History, however, tells a more complex story. According to the anthropologist An Mi-Jeong, both men and women dove prior to the dynastic era of Joseon (1392–1897). With the establishment of dynastic rule and the Confucian patriarchy, however, came a transference of ‘low-class’ labour to women. The uniformity of gender among chamsu divers, An asserts, is a ‘political product’. 5

During and after Japanese colonial rule, the working conditions for chamsu divers underwent important changes. On the one hand, the wider commercial routes and rising demand for sea products presented new economic opportunities for the divers, whose population surged throughout the early 20 th century. Girls and women were valued in the community, as can be seen in the Jeju proverb, ‘If a newborn is a girl, celebrate it with a pork-meal party; if it is a boy, kick his butt’. 6 The onslaught of Japanese fisheries, on the other hand, left the island with severe resource depletion. The chamsu now had to look elsewhere. Eventually, some boarded the Kimigayo Maru , a new cargo liner that launched in 1922 to connect Jeju and Osaka.

‘Coming to Japan at age 20, and without even an average life, I walked on the bottom of the sea with a coffin. Together with seagulls, I have lived through this year and that year, but this body, once young, has aged, under the sea’. 7

5 Mi-Jeong An, 済州島 海女の民族 誌 「海畑」という生活世界 (Chiyoda, Tokyo: Alphabeta Books, 2017), 32.

6 Ibid, 35. My translation.

7 Yong Kim and Jungja Yang, 海を渡 った朝鮮人海女 房総のチャムスを訪 ねて (Chiyoda, Tokyo: Shinjuku Shobō, 1988), 90. My translation.

28

These are the lyrics of a song composed by a migrant chamsu . Although the lives of these migrant divers do not surface frequently in records or media, we can see glimpses of their experiences in Japan thanks to several key works of documentation. In this article, I follow one such contribution, a book titled 海を渡った朝鮮人海女 房総のチャムス

を訪ねて ( The Korean Women Divers who Crossed the Ocean: Visiting the Chamsu in the Bōsō ) by Kim Yong and Yang Jungja (1988). Both of Zainichi roots, 8 the authors follow and interview Korean divers across the Bōsō Peninsula. How and why have migrant divers continued walking on the bottom of the sea with a coffin? The stories from the book delineate the turbulent lives of women in permanent precarity.

For the chamsu , sources of precarity were ample. Firstly, many of them lived in poverty, and their economic instability, in turn, made them targets for discrimination:

Secondly, the very nature of their labour was prone to instability. Many chamsu relied on the help of Korean managers who negotiated with Japanese authorities and landowners over fishing rights and property. Without proper local knowledge, however, these managers were at risk of frequent fraud and deception. When the fisheries coop (or kumiai ) took control of most fishing operations in the mid-20 th century, they frequently excluded the rights of chamsu divers from their legal framework. Ethnic prejudice kept the Korean migrants away from secure diving grounds.

‘The Japanese look down on us Koreans; they don’t consider us human. They’d say, ‘Oh, here’s a poor beggar.’ No house, no nothing; they don’t even speak the language’. 9

Furthermore, we must not forget that these women usually undertook the strenuous task of being at once a breadwinner, mother, and wife. It was not uncommon for their husbands to fall into gambling, turn to domestic violence, or disappear after their arrival in Japan. Most of the family burden fell on these women, who were also responsible for raising multiple children in a foreign land. Often, these children were born not in the hospital but in their own tiny huts, meaning they would grow up as invisible citizens deprived of social or political rights.

8 Zainichi 在日 (literally, “staying in Japan”) is a word used to refer to those ethnic Koreans who are permanent residents of Japan and either immigrated during Japan’s colonial rule over Korea or are their direct descendants.

9 Ibid, 26. My translation.

29

Economic poverty, ethnic discrimination, gender and family strains: these intersectional struggles haunted the Korean divers who crossed the ocean. I have used the past tense in this section since the source is more than several decades old and there are believed to be significantly fewer chamsu in Japan nowadays than in the mid-20 th century. Yet this assumption can be quite misleading. Many of the living conditions described here continue to weigh on the remaining chamsu today, perhaps even more so. What do their lives look like today? For that, we need more stories.

Regardless of how much their circumstances have shifted, one thing will not change: the lives of these Korean women have been inextricably entangled with those of Japanese ama and their colonial history. Not only were they colonial migrants; many chamsu were also forced labourers of imperial Japan. They contributed to the production of gunpowder by harvesting much-needed seaweed in the years of the Pacific War. Institutional forces uprooted them from their social and economic settings. The chamsu, then, confronted and negotiated their new realities in their own ways. These efforts did not come without deep wounds, poignantly depicted in the rest of the song quoted above:

‘Count with the fingers I shall, it has been 39 years since then. I decide to visit my hometown, but my father, my mother, and my brothers are all gone, dead, there is no place to return to, what can I do, tears come up, I visit my mother’s grave, only to find weeds growing thick and wild, big brother, big sister, I call their names, only to face the silence, not even ‘welcome home’, I search for the way home, but the tears won’t let me see.

I look in the north and the south and the east and the west, only to find that there is no one giving me the simple wish, of “have a safe journey”.’ 10

30

10 Ibid, 91. My translation.

31

Fig. 4 A diver gathering seaweed underwater.

Shared Histories Beyond the Ocean

Even a look as cursory as this article should suffice to say that, in contrast to how they are portrayed in Amachan , the lives of the ama are not as simply peaceful or joyful, nor as uniquely Japanese as some claim. Rather, behind the scenes is a shared history of transnational encounters rife with tension and anxiety. On the one hand, as they became involved in the state colonial fisheries policy, the Japanese ama not only went through economic exploitation by their managers, but spent night after night on their ships fearing clashes with Jeju locals. At the same time, the invasion led the Korean chamsu to migrate to Japan; many lost their connections with family and friends, and found themselves in extremely vulnerable conditions. In other words, women from both sides of the Korea Strait were drawn into often-violent circumstances by forces of the emerging modern world. And on top of all this were the inherent physical dangers of their work–the chamsu and ama continued to walk on the bottom of the sea with a coffin. Yet it would be wrong to see these

historical processes as only a story of despair or confrontation. It is also a story of their connections, shared traditions, and capacity to navigate through a changing world. I have interviewed an ama currently working and living in Mie Prefecture. Recalling her time at the last international Ama Summit, the ama told me that the Korean and Japanese divers came together and immediately shared a deep sense of friendly connection despite language barriers. ‘We share the same ocean. That is why we are friends’. 11 In the past, the crossing of the ocean brought about separation. Today, that same ocean is bringing people together despite all their differences. And this shared ocean only comes alive in the presence of the strength and tenacity with which these divers have negotiated their turbulent lifeworlds. It is perhaps by telling more stories about these lives underwater that we can begin to imagine the continuity–and renewed future–of this shared East Asian heritage.

11 An ama (anonymous) in an interview on 22 May 2022.

32

Suggested Readings

An, Mi-Jeong. 済州島 海女の民族誌 「海畑」という生活世界 . Translated by Soon-Im Kim. Chiyoda, Tokyo: Alphabeta Books, 2017.

Kim, Yong, and Jungja Yang. 海を渡った朝鮮人海女 房総のチャムスを訪ねて. Chiyoda, Tokyo: Shinjuku Shobō, 1988.

Martinez, Dolores P. Identity and Ritual in a Japanese Diving Village: The Making and Becoming of Person and Place . Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004.

Tsukamoto, Akira. 鳥羽・志摩の海女 素潜り漁の歴史と現在 . Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2019.

33

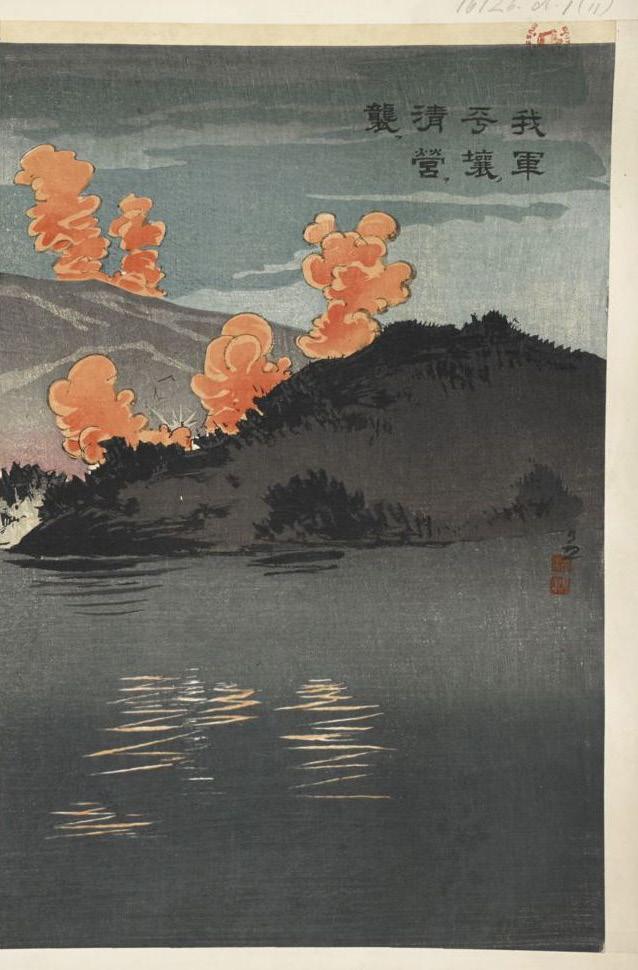

), December 1894; published

34

Fig. 1 Ōkura Kōtō 大倉耕濤 "Japanese Spirit": Bugler Shirakami, heavily wounded and facing death at the Ford of Ancheng, continues to sound the advance (Yamato-damashii : Shirakami rappashu Anjō-watashi ni jūshō shi ni nozonde nao shingun no rappa o fuku no zu 日本魂:白神喇叭手安城渡に重傷死に臨んで尚進軍 の喇叭を吹図

by Hasegawa Sumi 長谷川スミ. Ōban single sheet nishiki-e .

IN SEARCH OF THE TRUTH(?)

The Kubota's Illustrated Report on the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino–Japanese War (1894–1895) was a turning point in Japanese history. For Japan, the power balance of East Asia had shifted as the once powerful and influential Qing dynasty was defeated by another Asian power: the Empire of Japan. Considering the importance of this war, Japanese newspapers, such as the Kyoto Asahi Shinbun, dispatched journalists to the front to observe and document developments of the ongoing war. As a result, articles, reports, photographs, and woodblock prints were continuously published, while painters were also sent to the front to create visual reports. One such example is the Illustrated Report of the Sino–Japanese Battles ( Nisshin sentō gahō 日清戦闘画報 ; 1894–1895). 1 This woodblock-printed report was published in eleven volumes by Ōkura Yasugorō ( 大倉保五郎 ; 1857–1937) and drawn by Kubota Beisen ( 久保田米僊 ; 1852–1906) and his two sons, Kubota Beisai ( 久保田 米斎 ; 1874–1937) and Kubota Kinsen ( 久 保田金僊 , often 金仙 ; 1875–1954). This article discusses the production details of the report, shedding light on its war representations through comparison with other popular media of the time.

Historical Background: The First Sino–Japanese War

Bilateral tension between Japan and China grew during the early Meiji period (1868–1912) as Japan tried to become influential on the mainland. Initiating relations with Korea was their first step in this, but given Korea’s tributary relationship with China, this proved difficult. Following ongoing interference by both Japan and China in Korea’s national affairs, the Tianjin Convention was signed in 1885. This treaty meant that the two nations would withdraw their troops from Korea, and would notify each other in advance should they dispatch troops in the future. While the two countries kept a close eye on Korea, tension was temporarily subdued.

1 Literally, the Japanese reads ‘Japan–Qing’, which distinguishes it from the Second Sino–Japanese War. Generally in English, Sino–Japanese is used as a translation. In this paper, therefore, it refers to the First Sino–Japanese War and not the Second.

35 HISTORY / POPULAR CULTURE ARTS

Arend Bucher

Nevertheless, China and Western nations soon tried to gain influence over Korea again, and in 1894 the Donghak Peasant Revolution broke out as a result of the dissatisfaction felt by many Koreans towards their government. Both China and Japan sent troops into Korea to intervene, leading to military conflicts on 23 rd , 25 th and 29 th July. As a result, war was declared on 1 st August 1894. On land, the war took place in Korea and North East China, while

naval battles were fought in the Yellow Sea. The Treaty of Shimonoseki was concluded on 17 th April 1895, heralding the end of war, in favour of Japan. However, the fighting was not yet finished. Taiwan, which was conceded to Japan as a result of the war, did not accept Japanese rule. Accordingly, Japan went on to occupy Taiwan until November of the same year. Only hereafter can the First Sino–Japanese War be said to have completely ended.

Journalism and Media in Meiji-period Japan

Media, as in popular or mass media, has a fairly long history in Japan. Already from the beginning of the Edo period (1600–1868), there were illustrated books and loose printed pictures being sold mainly among commoners in the big cities. The latter were called ukiyo-e 浮世絵 (pictures of the floating world), or nishiki-e 錦絵 (brocade pictures) when printed in a full-range of colours. These prints can be seen as the precursors to modern popular media in Japan. Ukiyo-e lived on through the Meiji era, combining earlier fashions with new dyes, themes, and styles, influenced by the import of Western culture and goods. Ukiyo-e spread gossip and led fashion trends throughout its history, but from the 1850s onwards, news on Westerners and their culture started to be distributed through this medium. Information on earthquakes, wars, and international expos, too, was shared via

woodblock prints from the late Edo period and throughout the Meiji period. In this sense, the prints were comparable to newspapers, even tabloids.

Closer to news reporting were the kawaraban 瓦版 (tile prints) and shinbun nishiki-e 新聞錦絵 (newspaper brocade pictures). The former were sheet prints made using engraved tiles, while the latter were classic woodblock prints. Both combined image and text to spread news and gossip, often diluted with humour or sensationalism, forming something between an ukiyo-e and a newspaper. In short, one can say that even before the import of new, Western media during the Meiji era, a native foundation was already present and that it was developed further when Western methods were employed alongside domestic ones.

36

Among these Western innovations were the newspaper, photography, and lithography, of which the first was the by far the most prolific. Newspapers, in the modern sense, began to be published in Japan in 1868, and in 1871 the first daily newspaper was launched: the Yokohama Daily Newspaper ( Yokohama Mainichi Shinbun 横浜毎日新聞 ). By the end of the 1870s others followed, and magazines on all sorts of topics we published as well.

Photography had already been introduced to Japan as early as 1848, rising slowly in popularity during the 1850s and 60s. After the necessary exposure time was drastically shortened, thanks to dry gelatine plates, photography was used as a way of reportage from the early 1890s onwards. Natural disasters and the upcoming Sino–Japanese War

became the first main subjects for this new use of the medium. However, most war photographs depicted post-battle scenes or images otherwise unrelated to the fighting.

37

Fig. 2 Kubota Beisen 久保田米僊 and Beisai 米斎 . Chinese horse riders in battle, p. 20 from An Illustrated Report of the Sino-Japanese Battles, vol. 3, 2 December 1894; published by Ōkura Yasugorō 大倉保五郎 . Woodblock printed, ca 17 x 24 cm.

Lithography, another reproductive medium from the West, was first used in Japan in the 1960s, for Christian propaganda and for Western-owned newspapers (such as the Japan Herald). Once the Meiji period began, the military and the Ministry of Education ( Monbushō 文 部省 ) used it for publishing textbooks. By the end of the 1870s, the technology was also being applied to printing magazines, inserting pictures, commercials, and more. The medium’s success was utilised during the Sino–Japanese War, where lithographs depicting the war were printed, too.

One might wonder whether some media had to succumb to others, but during most of the Meiji era this was not the case. The Western media were often still developmental, so each medium had its own characteristics, with its own merits and demerits. Only by the late Meiji period had Western technology improved enough that some media, for example woodblock prints, had to give way and become niche.

Kubota Beisen was born in Kyoto, and went into training under Suzuki Hyakunen ( 鈴木百年 ; 1828–1891) to become a nihonga 日本画 (Japanese style painting) artist in the Shijō style ( Shijō-ha 四 条派 ). Though educated as a nihonga painter, Kubota showed interest in other media and activities as well. Not only did he master oil painting, known as Western style painting ( yōga 洋画 ), but he also drew cartoons and took on jobs for nishiki-e designs and illustrations in guidebooks. From 1878 on, he was in contact with people from various newspapers and magazines, and in 1889 he even founded The Kyoto Daily News (Kyōto Nippō 京都日報 ) with some comrades.

The journalist Tokutomi Sohō ( 徳富 蘇峰 ; 1863–1957) launched The National Newspaper (Kokumin Shinbun 国民 新聞 ) in Tokyo in 1890. 2 A year earlier,

Tokutomi had asked Kubota to join his company, as Tokutomi thought highly of Kubota’s work, and so the latter started working as a journalist in Tokyo. When the situation escalated in Korea, he was sent there together with his son, Kubota Beisai, by The National Newspaper in June 1894. Alongside contributing sketches and articles to the paper he was affiliated with, Kubota sold his work to other companies. He did not, however, stay very long at the front. By the end of July, Kubota had already temporarily returned home due to illness. He went back to the front in mid-August, but in early October travelled to Hiroshima, where he painted in the presence of the emperor at the imperial headquarters, never to return to the front.

38

Kubota Beisen: An Artist at the Front

From the time Kubota Beisen moved to Tokyo for work, he was aided by his two sons. The three together will be referred to, here, as the ‘Kubota studio’. The oldest son, Kubota Beisai, had gone to high school in Oakland, USA. After his return in 1889, he was schooled in nihonga , Chinese classics, and Japanese poetry in Kyoto, and subsequently went to Tokyo in 1892 to join his father. There he learned Western style painting and worked for kabuki magazines and print publishers. In June 1894 he set sail for Korea together with his father.

The second son, Kubota Kinsen, was educated at the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting ( Kyōto-fu Gagakkō

京都府画学校 ), which was co-founded by Kubota Beisen in 1889. He was also instructed by his father and went along with him to Tokyo almost immediately. There he, too, worked for The National Newspaper. Initially, he did not go to the front, but since his father had already returned to Japan by October, he was sent in his stead.

A Naval Battle Between Japanese and Chinese Warships ( Nisshin kan gekisen no zu 日清艦激 戦之図 ), 1893?; published by Komori Sōjirō

森宗次郎 . Ōban triptych (left sheet) nishiki-e

2 Previously, another Kokumin shinbun existed. However, this one was not founded by Tokutomi.

39

Fig. 3 Shunsai Toshimasa 春斎年昌

小

Kubota’s Children

An Illustrated Report of the Sino–Japanese Battles

An Illustrated Report of the Sino–Japanese Battles ( Nisshin sentō gahō 日清戦闘画報 ; hereafter NSG), is a series of picture books drawn and authored by the Kubota studio and published by Ōkura Shoten 大倉書店 , or more specifically, Ōkura Yasugorō ( 大倉保五郎 ; 1857–1937), from 1894 to 1895 in eleven volumes. The earliest volume was published on 1 st October 1894, and the last one on 6 July 1895. 3 The books measure 17 by 24 centimetres (height by width). Each volume consists of two main parts: a woodblock-printed section containing a handwritten introduction and an average of thirteen to nineteen pictures, followed by a section devoted entire -

ly to written information on the war, made using movable metal type. This writing serves as background information and complements the illustrations. From the fifth volume onwards, the pictures are accompanied by English captions printed using the moveable type, suggesting a possible foreign demand. 4 Indeed, Ōkura Shoten is known for exporting reissues of Japanese art to the West in book format, even displaying them at world fairs. It is thought that Kubota Beisen got in touch with the Ōkura company when they published books on Shijō paintings (for export), the painting school to which Kubota belonged.

40

Purpose and Historical Reliability

When looking at a series of books like this, questions arise over whether it is a reliable historical source, what the purpose of the authors and publisher was, and how it fits into the contemporary media landscape. The first is of course problematic, as it is impossible to make something objectively truthful. Especially in this case, where the images were usually drawn from the perspective of the reporter, implicitly supporting a certain point of view. Still, another issue arises. When reading the introduction to the first volume, written by Kubota Beisai, the overall goal of the series seems rather clear: he starts off by explaining how valuable it is, though often difficult and frustrating, to record current traditions and historical events, especially in a time of rapid change and modernisation (as the Meiji era was). 5 In other words, it seems as if

Kubota Beisai was aware of the importance the family’s work might hold as a historical record. He even goes on to openly criticise other painters and ukiyo-e artists in general for their often lax attitude towards depicting the truth. In this way he points out the possible harm it might bring to the historical understanding of future generations. Furthermore, he discusses his experience as a war reporter, how everybody at home inquires about what life is like at the front. He states that he wishes everyone could know about it, perhaps through his pictures. Thus, the purport of this work appears to be a historically accurate report.

Fig. 4 Kubota Beisen 久保田米僊 , Beisai 米斎 , and Kinsen 金仙 . Copy of a Chinese print of the Battle of Juliancheng, p. 26 from An Illustrated Report of the Sino-Japanese Battles , vol. 6, 29 January 1895; published by Ōkura Yasugorō 大倉 保五郎 . Woodblock printed, ca 17 x 24 cm.

3 These dates are based on those that can be found in the NSG copies of The National Diet Library and those in Ōtani Tadashi and Fukui Junko, Egakareta Nisshin sensō: Kubota Beisen ‘Nisshin sentō gahō’ eiin/honkokuban (Osaka: Sōgensha, 2015).

4 The combined use of moveable metal type printing and woodblock printing happened regularly in the late Meiji period. It was mainly used to add English (or other Romanised) text to images.

5 The westernisation of Japan in the Meiji period is also called bunmei kaika 文明開化 , often translated as civilisation and enlightenment.

41

Yet a few facts contradict this. To begin with, Kubota Beisen was not present at the front for a large part (see above), and nor did his sons, Beisai and Kinsen, witness all the events. The Battle of the Yellow Sea (vol. 4), most of the fifth volume, half of the seventh volume, the tenth volume, and the majority of the eleventh ( gaisen hen 凱旋編 , or triumph volume ) were not drawn based on their own first-hand experiences. Moreover, war reporters were generally not present at the battles themselves, but watched from afar or based their reports on the stories of soldiers and what they could see after the fighting. This becomes clear in the illustrations contributed to their articles in The National Newspaper. These mainly depict landscapes and commoners, not the battles themselves. The pictures in the illustrated report, however, do regularly depict the battles, often intimate -

ly. So there seems to be a discrepancy between what the two forms of media represent, despite being produced by the same people. Though the purported goal of the series is to be truthful, it is in fact a rather heroic, glorified version of the war, similar to many war prints created at home during that time. Ultimately, it cannot be seen as a reliable historical source. Why there is this contradiction between the pictorial content and the written introduction is not clear. A simple possible answer could be that marketing it as a reliable source was more appealing to customers, and would yield more revenue. What is also curious is that the name of the series emphasises the fighting and action of the war instead of the war as a whole, by using sentō ( 戦闘 , battle) instead of sensō ( 戦争 , war). This is interesting as sensationalism remains a contentious topic to this today.

42

Other War Picture Books

The NSG was not one of a kind. Japan already had a well-established tradition of picture books, dating back to the early Edo period, and Ōkura Shoten was not the only shop to produce illustrated books on the war. When looking at the advertisement section of newspapers from that time, one can immediately see how other companies dedicated themselves to publishing reports on the war in a variety of ways. The Kubota studio’s work was also published across two volumes by Minyūsha 民友社 , the larger company that ran The National Newspaper, as A Record of the Sino–Japanese Armies ( Nisshin gunki 日清 軍記 ; 1894–1895). The cultural historical magazine, The Illustrated Report on Manners and Customs ( Fūzoku Gahō 風 俗画報 ), similarly published volumes on Korea and Taiwan. Other companies, like Hakubunkan ( 博文館 ) and Shunyōdō

( 春陽堂 ), published illustrated reports with copperplate-printed photographs. Furthermore, some companies published volumes without pictures, at least according to the descriptions in their advertisements: for example Sino–Japanese War History ( Nisshin senshi 日清 戦史 ) by Keizai Zasshi-sha ( 経済雑誌社 ).

Whether or not all of these companies sent their own reporters to the frontline is not clear, but in the end a total of 193 Japanese reporters were sent to document the Sino–Japanese War, among them 16 painters and 5 photographers. 6 In other words, it is clear that the Japanese journalism world was flourishing, with a wide variety of reports by different publishing companies as a result.

6 Ōtani, Tadashi, ‘“Nisshin sentō gahō” no seiritsu to sono naiyō ni tsuite’ in Egakareta Nisshin

sensō: Kubota Beisen ‘Nisshin sentō gahō’ eiin/honkokuban

(Osaka: Sōgensha), 435

43

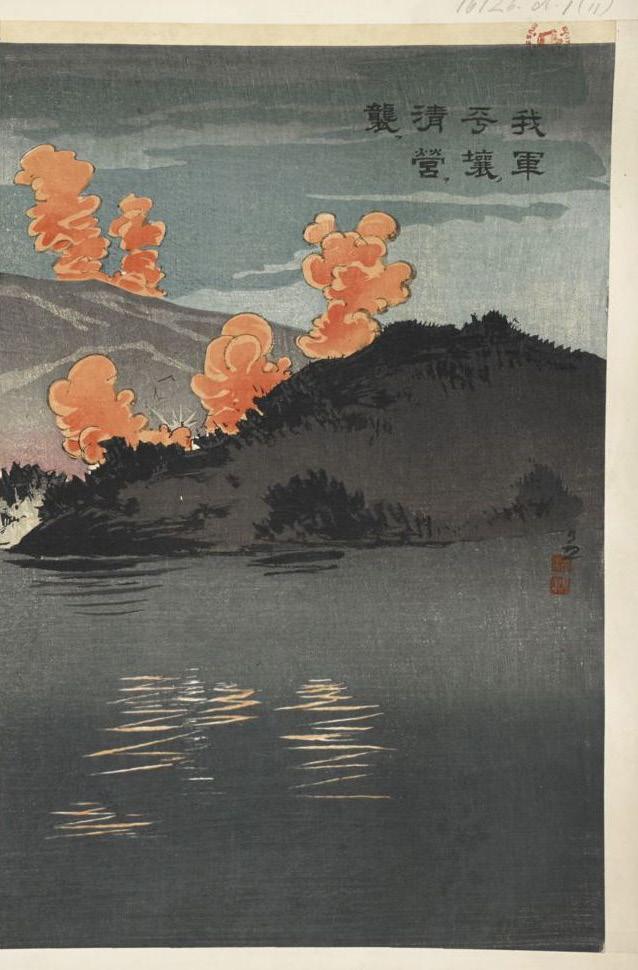

NSG in Woodblock Prints?

It is said that the Sino–Japanese War woodblock print artists often used NSG as an informational or inspirational source for their designs. A striking example of this would be a print by Kobayashi Kiyochika ( 小林清親 ; 1847–1915) depicting The Battle of Pyongyang (15 th September 1894), which strongly resembles pages sixteen and seventeen of the third volume of NSG (Fig. 5 & 6). However, it remains uncertain whether the war prints really used this book series as a source, and the extent to which such is visible.

Foundation for this argument seems to be lacking. Interestingly, very few pictures bare a resemblance in composition, perspective, design, or specific subjects. Only six prints strongly, and five others slightly, resemble the NSG drawings. Given that there are approximately 160 images in NSG, only 6.8% of the NSG drawings could have perceivably served as a source material. 7

44

Fig. 5 Kubota Beisen 久保田米僊 and Beisai 米斎 . The Battle of Pyongyang, p. 16-17 from An Illustrated Report of the Sino-Japanese Battles , vol. 3, 2 December 1894; published by Ōkura Yasugorō 大倉保五郎 Woodblock printed, ca 17 x 48 cm.

Besides the numbers, there are other factors that need to be taken into account. The printing industry was a fiercely competitive one. Publishers wanted to be the first to publish works on a new topic. In comparison to newspaper articles, other books (that were advertised in newspapers), and many individual woodblock prints, the NSG was released rather late, when most of the depicted events had long since passed. Logically, most publishers would not wait for the NSG to be published just for reference sake.

Moreover, strikingly, four out of six of the strongly similar pictures depicted events that none of the Kubotas reported on. In two of these cases, the publication dates confirm that the prints were issued before the NSG. Instead, it could be said that the Kubota studio used war prints as a source for events at which they were not present. Another explanation could be that the Kubotas and other print artists used the same separate report as a source. Or it might well be a coincidence.

Taking the above into account, the series did most likely not serve as a pure reportage, with the purpose of conveying new information. Rather, this report might have been aimed at people with an interest in war prints as a collector’s item. This is strengthened by the fact that Kubota Beisai introduced the series as being more reliable than many other visual materials. It also seems probable that it was directed at people who preferred nihonga above Western style paintings or the average war prints, as the Kubotas were the only nihonga artists at the front. So, though the NSG is a fascinating part of publishing history and there are many beautiful pictures in there, caution is needed when interpreting its contents, regardless of Beisai’s claims

7 For this article, the author analysed all the drawings of the ten NSG volumes (the triumph volume does not depict war scenes, so is not included) and compared them to Sino–Japanese War related prints from various databases and books that depicted the same topics.

45

46

Fig. 6 Kobayashi Kiyochika 小林清親 Japanese army launches a night attack on Pyongyang ( Waga gun Heijō Shin'ei o osou 我軍平壌清営襲 ), October 1894; published by Matsuki Heikichi 松木平吉 . Ōban triptych nishiki-e

Suggested Readings

Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) and British Library (BL). Web exhibition. The Sino–Japanese War of 1894–1895: As Seen in Prints and Archives . Accessed 21 October 2021. https://jacar.go.jp/english/jacarbl-fsjwar-e/index.html.

Ōtani Tadashi and Fukui Junko. Egakareta Nisshin sensō: Kubota Beisen ‘Nisshin sentō gah ’ōeiin/honkokuban . Osaka: Sōgensha, 2015.

Paine, S. C. M. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Swinton, Elizabeth de Sabato and Worcester Art Museum. In Battle’s Light: Woodblock Prints of Japan’s Early Modern Wars . Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1991.

47

ŌMAMEDA TOWAKO AND HER THREE EX-HUSBANDS 大豆田とわ子と三人の元夫

Fengyu Wang

Here’s what happened this week:

Ōmameda Towako loathing the windowpane when it slid out of the frame…

Ōmameda Towako pouring salt into the coffee of her ex-husband…

Ōmameda Towako watching her ex-husbands fighting using broccoli…

Ōmameda Towako waking up in the morning with her ex-husband…

Screenwriter Sakamoto Yūji’s ( 坂元裕二 ) 2021 TV drama, Ōmameda Towako and Her Three Ex-Husbands , starts off with its protagonist (played by Matsu Takako 松たか子 ) trying to unlock her late mother’s laptop to find a good photograph for the latter’s funeral. Hindered by the security question – the name of their first pet – she resorts to contacting her three ex-husbands, some of whom she hasn’t seen for a long time. Quirky, clumsy, but otherwise quite loveable in their own respects (thanks to great performances by Matsuda Ryūhei 松田龍 平 , Kakuta Akihiro 角田晃広 , and Okada Masaki 岡田将生 ), they reconnect with Ōmameda, rekindle old passions, and reappear in her life as endearing old acquaintances, often bordering on personae non gratae. The assembling of the eponymous four (abbr. Mameotto まめ 夫 ) opens a whole series of unexpected

Written by

Sakamoto Yūji

Starring

Matsu Takako, Matsuda Ryūhei, Kakuta Akihiro, Okada Masaki

Directed by

Nakae Kazuhito, Ikeda Chihiro, Taki Yūsuke

Number of Episodes

10

Release

Spring, 2021

Production Network

Kansai Telecasting Corporation

events and encounters, filled with dynamic dialogues, whimsical epigrams, and sporadic critiques (both mutually exchanged and self-inflicted) that are just as intense, and as farcical, as the exes’ broccoli fight.

48

FILM POPULAR CULTURE / REVIEW

Fig. 1 Illustration after the poster of Ōmameda Towako and Her Three Ex-Husbands , Kansai Telecasting Corporation 関西テレビ. Illustration: Fengyu Wang.

From the most trivial to the absurdly theatrical conflicts, each of Mameotto ’s ten episodes opens with a comic montage, narrated by an amusingly candid yet scandalising voiceover. On one occasion, Ōmameda opens a kitchen cupboard overhead only to be greeted by a cascade of spaghetti pouring out of its packet; on another, she is taken into a police car with her neighbours looking on, while the voiceover joyfully chimes in: ‘Ōmameda Towako riding that thing that only the chosen people can take.’ Playing with the weekly format of TV drama, these vignettes, with the voiceover announcing ‘I will show you this week’s events in detail’, are both a parody of news reportage and an audio-visual appetiser. Presented in such a series of stylish snapshots, they capture your attention, raise your expectation, and put you in a mood for more quips and skits and high drama. However, as the episodes unfold, what appeared most dramatic in the previews often turns out to be surprisingly mundane once events are played out, situations quite naturally caused and then resolved in the flow and folds of life, one already full of urgency and tribulation. It is those trivial, everyday bothers that carry the emotional resonance while driving the narrative. Ōmameda’s most cordial exchanges with other characters, especially her new

dates (guest stars, each a surprise and a treat), concern shared experiences of only the smallest things – the unsynchronised body-turning exercises, or the soy sauce bags that are impossible to tear open without spilling all over. Just as we identify with Ōmameda when she turns a cling film roll over and over to find its loose end, these small things bond characters with each other as much as they connect them to us. Ōmameda’s hindered relationship with her daughter Uta (Toyoshima Hana 豊島 花 ), however, is also manifest when she fails to connect with the latter by trying to share her experiences with smartphones. To questions like ‘don’t you have that kind of photos on your phone that you took by accident?’, teenage Uta reacts with only a confused and callous ‘no’.

49

Filled with quips and quibbles, Mameotto is lauded as a vanguard of the so-called ‘idle talk drama’ ( zatsudan dorama 雑談ドラマ ). Similar to the ‘mumblecore’ subgenre, trendy nowadays in American independent cinema, 1 the ‘idle talk drama’ also features chatty, discursive dialogue that evokes the casualness of everyday life. Without an overarching narrative or tightly crafted plot, characters instead develop through a series of atomic, sometimes unrelated events that formulate the larger, more intimate fabric of their personal lives. But unlike its American counterpart, ‘idle talk drama’ does not shy away from stagy, artful designs and devices.

Thought-provoking, epigrammatic reflections are scattered all over the series and sometimes spilled lightly over sips of sake. The remark by Ōmameda’s

best friend Kagome (Ichikawa Mikako 市川実日子 ), that ‘divorce is proof that one can live without lying’, snaps back critically at the social stigma attached to being a divorced woman, but is delivered with such leisure as she tipsily tends a piece of meat on a barbeque grill.

1 Mumblecore films are most known for unscripted, naturalistic dialogues and delivery, low-budget production, and anti-climatic plotlines. Emblematic of this subgenre, among others, are Joe Swanberg’s 2007 drama Hannah Takes the Stairs , and Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s 2013 comedy Francis Ha . For more on mumblecore, see Dennis Lim, ‘A Generation Finds Its Mumble’, The New York Times , August 19, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/19/movies/19lim. html, and David Denby, ‘Youthquake: Mumblecore movies’, The New Yorker, March 9, 2009.

50

Fig. 2 The three ex-husbands of Ōmameda are having an idle talk. Illustration after a screenshot of Mameotto, Ep. 1. Illustration: Fengyu Wang.

Such deliberateness is also manifest in the flow of narrative. The three potential dates for the ex-husbands are introduced in such a concerted manner at the end of the first episode, that they seem like a triple dea ex machina, critically customised for this triad of solipsistic divorcées. Coy, inert, tangled up with the past, the three men struggle to proceed with their new lives, let alone their new dates. They keep falling back on their ex-wife Ōmameda while constantly accusing the other two of having ‘lingering affections’ ( miren 未練 ). After weeks of probing and provoking, the three ladies finally manage to corner the deserters during a dumpling party, with their soul-shaking interrogation: ‘can you imagine dating someone like yourself?’ As the three divorcées finally start to reflect hard on themselves and brace for change, the three women leave the party and soon after – just as resolutely, but in a quiet and abrupt manner – exit the show to move on with their own lives. All of this takes place while the biggest mid-show conflict of Ōmameda’s career and relationship is playing out elsewhere, but as the audience we never get to see how it’s resolved. Instead, in this wonderfully conceived Mameotto episode where Ōmameda herself is almost entirely absent, we stare at a bizarre gathering of the orbiting characters, making dumplings as well as life decisions. And when we come back to her side of the story towards the end of the episode, the life of Ōmameda, too, has already moved on.