6 minute read

Fleeing Civil War

In Search of Peace and a New Home in America

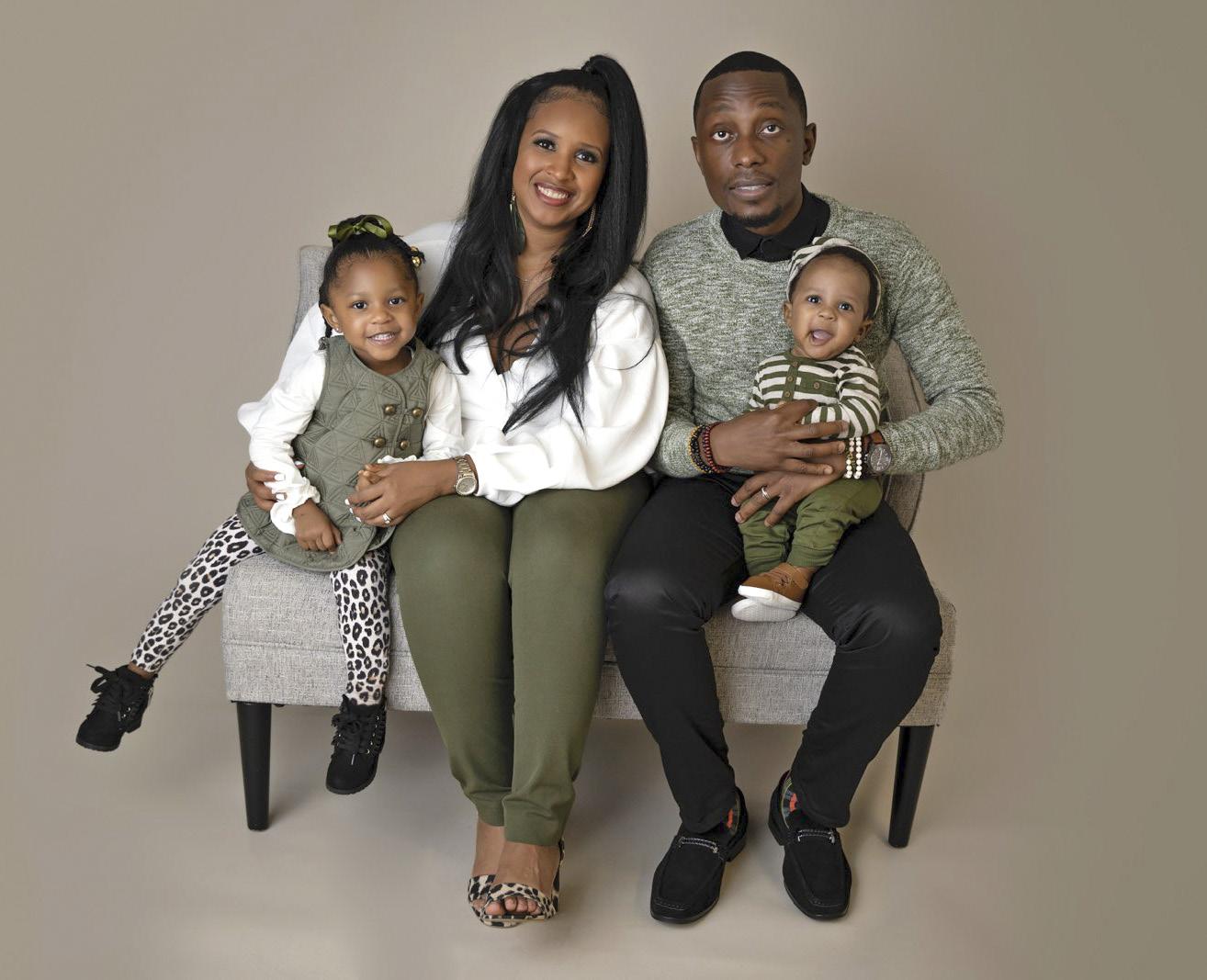

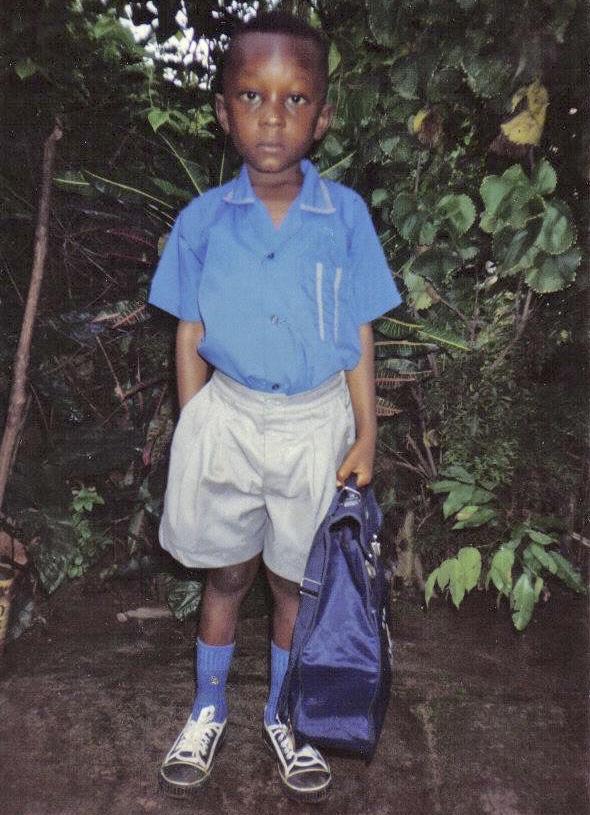

Sam Smith, 10, and his sister, 12, Dehkontee Smith, when they came to the U.S. in February 1997 Sam Smith, Jr., with his wife Brittany Smith and their two children.

By Angela Lindsay

Tens of thousands of refugees flee to the U.S. from other countries every year for a variety of reasons. Some are escaping war and gang violence. Others may be seeking refuge from persecution or other traumatic circumstances. But what happens to refugees after they arrive here? For Sam Smith, Jr., coming to America began as a scary and unexpected journey, but ultimately provided a brighter future for him and his family.

A native of Monrovia, Liberia, Smith became a refugee at 3 years old when civil war broke out in his homeland. From there, he and his mother moved throughout several countries in West Africa such as Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast where he met his older sister (two years his senior) who had already fled there with their grandparents.

As a refugee in Africa, Smith said he and his family were basically nomads, moving from camp to camp where they lived in makeshift structures inside gated areas. They remained in these various camps until the war spilled over into those countries as well, and they had to move again. In addition to this physical upheaval, Smith lost a younger sister to illness during the civil war which he says still affects him, especially around her birthday, as they were very close.

When Smith was 10 years old in 1997, he and his older sister fled to the U.S., leaving his mother behind. (In 2006, his mother relocated to Detroit, where she currently resides). His father, who had already moved to Detroit before the civil war began, spent everything he had to cover the high expense of getting Smith and his sister to the U.S. After obtaining visas, Smith and his sister endured several blood tests for the U.S. government to ensure they were, indeed, his father’s

—Sam Smith

children. When his mother, grandmother and other family members took Smith and his sister to the airport, they asked a random couple, who was also traveling to America, to look after Smith and his sister. The couple agreed.

Living in America

“One thing a lot of Liberians will tell you is when they talk about the United States in Liberia, you would think it’s like Heaven—everything is gold-plated and you have money falling from the trees!” he said. That’s how I grew up knowing what America was.”

However, that is not what Smith found when he arrived. Instead, he faced a barrage of bullying in the U.S. Although he already spoke English, Smith had a heavy accent which, among other things like his attire, caused him to be teased in elementary and middle school and called names like “African booty scratcher,” he said.

Making the transition to this country was difficult for Smith. Although he had never met his father before arriving in America, that’s who picked him and his sister up from Kennedy International Airport in New York and drove them to Detroit. Growing up, Smith and his family were considered lower middle class and lived in the Detroit projects for a while. To help his children get acclimated to their new environment, Smith’s father decided to hold him and his sister back a grade. Smith faced a sharp learning curve and “trying to fit in” was Smith’s most difficult challenge. He was suspended from school for a week for bringing a razor blade to sharpen his pencil, a common practice in Africa. He also had to adjust to saying things a bit differently, like using the word drinking “straw” instead of “tube.” Changing his thick accent was something Smith said he absolutely had to do. That’s when he learned to “code switch” by speaking with his Liberian accent around his family and with an American accent around his new friends.

Smith, who is currently the director of external engagement at the United Way of the Central Carolinas, has been in Charlotte for 8 years now. He moved to Charlotte to escape the cold weather in Michigan and because of the city’s growth and potential. Though he has not returned to Liberia, Smith said he plans to travel there for the 25th anniversary of his departure from his home country.

Left: Sam Smith at 6 years old on his first day of school in Monrovia, Liberia. Right: Detroit was Sam Smith's first home in the U.S. He has lived in Charlotte for eight years.

Fitting in

While refugees work hard to embrace their newfound culture, Smith urges Americans to become more educated about the plight of refugees as well. He encourages people to get involved with local organizations like International House, where Smith serves on the Board, and Refugee Support Services (RSS). Volunteer opportunities also exist with Carolina Refugee Resettlement Agency, Catholic Charities Diocese of Charlotte, ourBRIDGE for Kids, International House, Make Welcome, and Welcome Home CLT, said Lindsay LaPlante, interim executive director of RSS.

To be granted refugee status in the U.S., it must be determined through a lengthy vetting process that people seeking asylum are coming from situations of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group (such as LGBTQ+ individuals), or political opinion, said LaPlante.

From October 1, 2020, through March 31, 2021, North Carolina welcomed 91 refugees mostly from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Honduras, Ukraine, El Salvador and Moldova, said LaPlante. She agrees with Smith that increased awareness about the lives of refugees in this country would increase support for asylum seekers, and their volunteer involvement with organizations that help refugees would result in improved support for the plight of refugees. To help educate people about the plight of refugees and combat the misinformation about them in the media, RSS offers basic trainings called “Refugee 101” for groups that are interested in learning about global, national and local refugee issues.

“It’s important that we treat each other with dignity,” Smith says. “You never know what somebody’s circumstance is and just because a person isn’t from your country or you feel like the person doesn’t fit in with you, doesn’t mean that you look at them differently,” he said. Often refugees are working hard to support family members back home who can’t risk traveling to another country like the U.S., Smith said. They’re also trying to make a better life for themselves and their families in this country.

“So, just treat them with respect,” Smith said. “Treat them with dignity. Be sympathetic with them and open your ears to learn about the situation. I think if you’re educated about the situation, you may sympathize better with them and the struggle they have endured in being a refugee.” P

@charlottesgotalot charlottesgotalot.com