5 minute read

Women's Work

Heather Wastie shines a spotlight on the women often overlooked in the history of inland waterways restoration

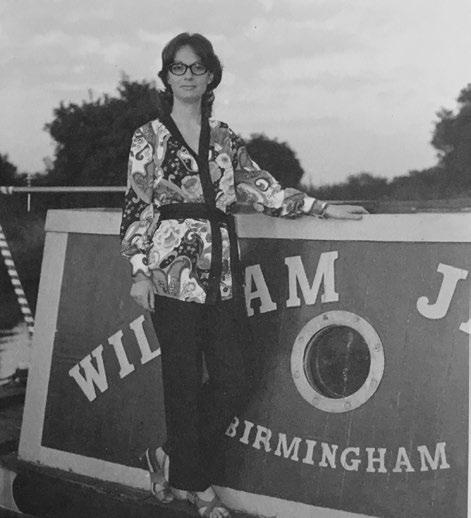

It is the weekend of 26th/27th September 1970. Margaret has driven her Mini to Parkhead, a derelict industrial area on the Dudley Canal, waste tip for Doulton’s ceramics. The whole area is buzzing with hundreds of enthusiastic workers clearing the locks. On the side of one of the locks there’s a small red tent belonging to Tina and her husband, Derek. Their boat is moored too far away to sensibly commute, so they decided to spend the weekend living under canvas in the middle of the action. Tina and Derek are kneeling on the grass in white boiler suits, leaning over the side of the lock. As they haul up heavy rubbish and buckets of debris from the bottom of the lock, they commiserate with the muddy volunteers down below, knowing their turn will soon come.

Meanwhile Margaret – keen to help clear the vegetation – has picked up a sickle. They say a bad worker blames his tools, but in this case Margaret was justifiably disdainful of the implement in her hand: “Well, you’d have had a job to cut soft butter with it.” She set to work doing something about it – and word soon got round. Now in her 80s, Margaret has vivid memories of that day, when she had set out to dig but ended up being “the woman who sharpens the sickles”.

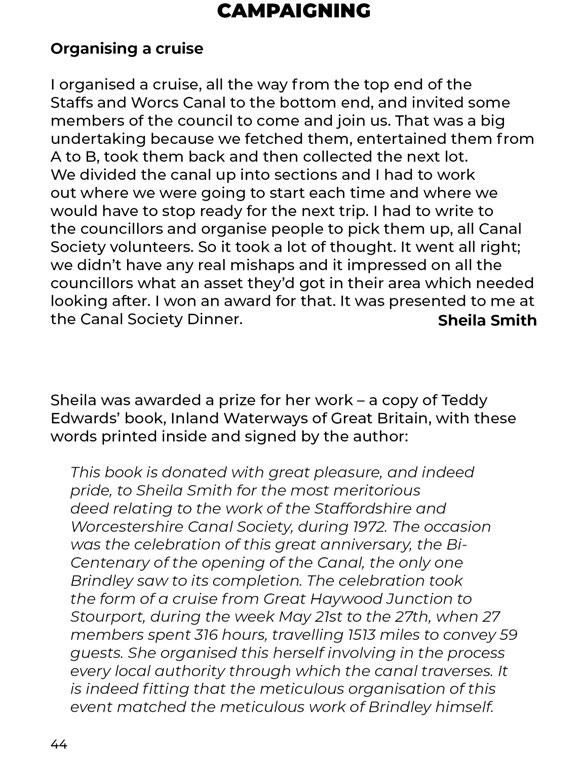

Both Margaret and Tina agreed to be interviewed for a research project entitled ‘I Dig Canals’, run by Alarum Productions in 2019/20 with financial support from National Lottery Heritage Fund. The event they described, which took place exactly 50 years ago, was called the ‘Dudley Dig & Cruise’. Another volunteer that weekend, Sheila, told us that the evening before she had made a treacherous 2-mile journey with her husband Alan on their ex-working narrowboat, Laurel. Her onboard logbook recounts: “Negotiated canal from Bumble Hole to Hawne Basin ready for Dudley Dig & Cruise. Experienced quite a lot of difficult patches with rubbish and scours [factory discharge pouring into the canal]. Finally arrived in darkness to rousing cheers.”

Sheila will no doubt have spent much of that journey lifting or leaning on a heavy shaft, pulling a rope or shifting her slight frame to rock the boat and keep it moving, until they eventually made it to the small gathering waiting for the cruise next day. She certainly kept fit, and to this group of enthusiasts a ‘cruise’ involved rather unglamorous onboard activities!

At breakfast-time the next day, the Mayor of Warley, together with other VIP guests, boarded Laurel. Leading a procession of four narrowboats, Laurel retraced the 2-mile journey of the night before, plus a further 3 miles to Parkhead – the site of the Dig – arriving at lunchtime. Sheila’s job was to provide refreshments for everyone on board as well as chat to guests en route, impressing upon them the importance of the stretch of canal they were travelling along.

Sheila and Alan are my parents. I was 14 at the time and wasn’t on board because I was taking part in a punishing 20-mile sponsored walk to raise money for the National Waterways Restoration Fund. The sum raised – £250 – was later donated to the Dudley Canal Trust (as it was then called) to help pay for the restoration of Dudley Tunnel. (The tunnel was reopened in 1973.)

Four Mayors in a Mini

Once the Mayor of Warley and other dignitaries had completed their official duties, they needed to get back to their starting point. Someone asked if anyone had a car. Margaret – who by this time had sharpened quite a lot of sickles – said yes, she had a Mini. In a nutshell (no pun intended), Margaret gave them all a lift: “I ended up with four mayors – none of them small – in my Mini. I put the biggest one in the front with me, and the other three squashed in the back somehow. The joy of the situation was arriving at the point where all the official cars were, with the official chauffeurs, and the look of sheer amazement on their faces.”

Accounts like these – fascinating, touching, funny and occasionally heartstopping – shed light on some of the volunteer roles women took on to further the cause of canal restoration in the Black Country and beyond. During the ‘I Dig Canals’ project, we recorded 19 long-form oral histories and several shorter ones which (once it is possible) will be available at the Canal & River Trust Waterways Archive in Ellesmere Port, completely transforming the currently available resources. To put it simply, there will be a women’s archive where previously there was not.

Covid hurdles

NLHF money enabled us to recruit, train and work with a dedicated group of 14 volunteers, as well as improving our own skills in oral history and documentary research. While I concentrated on the interviews, my co-director of Alarum, Kate Saffin, focused on documentary research, spending time at the National Archive in Kew and searching other collections in the Black Country for information and stories about the roles women took on more widely. Dudley Canal & Tunnel Trust supported us by generously donating premises (and a boat on one occasion) for our events. We had excellent training from Julia Letts, a very experienced oral historian and BBC radio producer, were able to employ our favourite filmmaker, Erin Hopkins, and provided work experience to a talented young designer, Laura Ndjoli, who created our logo.

When coronavirus struck, we were, thankfully, nearing the end of the project but were forced to cancel final public celebrations. However, this meant we were able to put more time and energy into a 56page book (snippets appear on the following pages), a short film and a series of 15 podcasts using extracts from the interviews. Details of these can be found on our website alarumtheatre.co.uk.

Inspired by the women whose stories we tell, Kate and I, together with project manager Nadia Stone, like to think we have embodied their never-say-die attitude. “Nothing was impossible in those days,” said Tina in her interview, “and it wasn’t impossible because we actually changed people’s minds.”