14 minute read

Cromford Canal

Restoration feature

As we once again use the reduction in WRG work to take a wider look at projects,

Restoration Feature: Cromford Canal

When we featured the Buckingham Canal in the last issue, I remarked on what a pleasant change it was to be able to report on a restoration where for once we will be able to ‘start at the beginning’ with a reopening in the not too distant future at the very start of the canal, where it connects to the navigable network. And this time we’re looking at another of those rare cases: the next major project on the Cromford Canal should see boats from the national network heading up a newly built pair of staircase locks within the next few years. But let’s go back to the start... The restoration back-story: From the above, the Cromford may sound like the sort of ‘start at the beginning’ project that canal restorers dream of (not to mention those of us boaters who are itching to navigate some new water!) but it hasn’t always been that way. Over the last half century it’s often been the familiar story of working on dead-end sections apparently in the middle of nowhere, simply because that was seen as the most practicable option for making progress with the resources available at the time.

Having said that, in fact the very first reopening of a section of the Cromford was actually a case of ‘start from the beginning’ too. It’s not generally seen as a part of the Cromford Canal at all, but Langley Bridge Lock and Great Northern Basin at Langley Mill, restored by the Erewash Canal Preservation & Development Association and reopened in 1973 to create a new terminus for the Erewash Canal (its own terminal basin having been filled in), was historically the very first part of the Cromford Canal, which met the Erewash (and also, to further confuse things, the former Nottingham Canal) at this point.

Over the years, that initial short length

The Cromford Canal was authorised in 1789 and built to connect the textile mills in Cromford, the ironworks around Butterley and the coal mines in the Pinxton area to the Erewash Canal (opened in 1779) at Langley Mill - and thereby to the Trent and to Nottingham. It was an expensive canal to build, with four tunnels including the 3083 yard Butterley Tunnel and sizeable aqueducts, and cost double the orginal estimate. However once it was open in 1794 it was an immediate success, helped by the Nottingham Canal and Derby Canal providing links to those cities. Proposals to link it to the Peak Forest Canal via a new canal crossing the Peak District proved impracticable, but instead an unusual early railway using horse haulage and rope-worked inclines, the Cromford & High Peak Railway, was opened in 1831 to provide this link. However by the 1840s the canal was feeling the effect of competition from more conventional railways, freight tolls were reduced in a bid to retain trade, and in 1852 the canal sold out to a local railway. In 1889 mining subsidence temporarily dosed Butterley Tunnel, then a second tunnel collapse in 1900 was not repaired. Some local traffic continued for some years on both sides of the tunnel, but in 1944 the then owners the LMS Railway officially abandoned it The southern length was subsequently filled in; the rest left to decay.

Cromford Canal

we feature a restoration that’s about to take a step forward - from Langley Mill

has been gradually extended to create the mooring basin, boating centre and focus for ECPDA that it is today.

But at the same time the restoration was happening elsewhere. In the 1970s the Cromford Canal Society, formed with the aim of restoring the canal, began work at the far end at Cromford Wharf, where the canal had survived in better condition than some of the lengths further south, and restored a section from there to Leawood Aqueduct over the River Derwent. They also took on the restoration of the Leawood steam pumping station, and set up a trip-boat operation on this mile and half length, based at Cromford Wharf. Restoration continued on the next section from Leawood to Gregory Tunnel and beyond, but practical problems of overtopping of the bank where the canal runs along the Derwent valley side following

Cromford Canal

Length: 14½ miles plus Pinxton Arm 3 miles Locks: 14 Date closed: between 1900 (end of through traffic over full length, Butterley Tunnel blocked) and 1944 (canal officially abandoned)

Sawmills narrows work site

Beggarlee Project Site

e Map by Friends of the Cromford Canal

heavy rain, coupled with disagreements within the group, led to the ending of work and later to the demise of the society. The trip boat subsequently ceased operation, but the rewatered length was retained as a nature reserve.

A few years later there was a further attempt to get restoration work going, this time concentrating on the length where the canal climbs to its summit at Codnor Park Locks then runs alongside Codnor Park Reservoir - but flood

Pictures by Martin Ludgate unless credited

Trip boat Birdswood at its home mooring at Cromford Wharf

relief work involving removing the top lock and lowering the water level in the lake put paid to these plans.

Finally the present active restoration group, the Friends of the Cromford Canal, was launched in 2002. To understand what they were up against, let’s quickly look at the state that the canal had got into by then. At the south end, it had been blocked not far beyond the end of the basin at Langley Mill by the new A610 main road built in the early 1980s to bypass Langley Mill. Most of the section from there to Ironville including locks 13 to 8 (we’re counting downwards - Langley Bridge Lock was No 14) had been largely obliterated by opencast mining and would need to be rebuilt from scratch, but at least the line was unobstructed and the towpath survived. Codnor Park Locks 7 to 2 were generally in fair condition considering how long they had been shut, but the top one, Lock 1 had been removed. The length from the top of the locks alongside the reservoir to Butterley Tunnel survived although silted and overgrown, as did much of the Pinxton Arm which branched off north and eastwards along the dam of the reservoir (although parts of the arm have since been lost to opencast mining - see below).

Butterley Tunnel was in poor condition, having suffered the same fate as Norwood Canal on the Chesterfield and Lapal on the Dudley No 2 Canal: a series of collapses caused by mining subsidence, eventually resulting in attempts to keep it open being abandoned and through navigation ceasing around the year 1900. Beyond the tunnel, a length in mostly fair condition led westward to Sawmills, beyond which the Bulls Bridge embankment and series of aqueducts crossing the Amber Valley had suffered from the demolition of the main road and railway spans. As the canal turned west again, another short length had partly disappeared under a chemical works; however from there northwards all the way to Cromford Wharf the canal was in water and in good condition, maintained by Derbyshire Wildlife Trust - albeit with an outlook on the future of their length of canal which wasn’t seen as likely to be terribly positive about the idea of reopening to powered boats.

Feeling that there was no point in taking a confrontational attitude with wildlife organisations that had preserved the northern part of the canal since the demise of the original restoration group, but at the same time not seeing much hope of practical progress on the largely obliterated southern end, FCC started in the middle. Supported by WRG volunteers (including a couple of Christmas camps), there was scrub clearance on the length between Butterley Tunnel and Codnor Park. A summer camp and several

visiting weekend working parties rebuilt one side of the Sawmills Narrows, a stone-sided narrowing of the canal built as a gauging point where boats were checked for tonnage (by measuring their displacement) and tolls were calculated. Some initial work took place at Codnor Park Locks - again supported by Canal Camps. And meanwhile on the northern length, the Friends carried out work on the Derwentside side weir between Gregory’s Tunnel & High Peak Junction, while the entire section was dredged in support of its nature conservation value by the County Council.

But with the latest project, as you’ll see below, we’re finally back to where we started: extending navigation northwards from the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill.

Where are we at now? The northern

length now once again has a regular tripboat operation (horse-drawn on special occasions), run by FCC and operating between Cromford and Leawood. The section from there to Ambergate , while not maintained to full original level, is also in water as a nature reserve and has been dredged. The Chemical works which straddled the route at Ambergate has now gone, but there are the two missing aqueducts (and reinstating the railway span is made more complicated by on-off plans to electrify the section of the Midland Main Line from Kettering to Sheffield, which this forms part of. One wall of the Sawmills narrows is rebuilt, and a minicamp by WRG NorthWest diverted the towpath around the offside to facilitate rebuilding the second wall in the future. Butterley Tunnel is still as wrecked as ever, the lengths east of the tunnel are less overgrown than they were, sadly a promise to reinstate part of the Pinxton Arm as remediation work following the opencast mining hasn’t been kept, but the flight of locks appear in decent condition with initial work carried out. As we said earlier, the last few miles and locks are missing but unobstructed. And they lead to the A610 blockage - but that no longer seems the obstacle that it once was...

So what next? Although it would be good to rebuild the second wall at Sawmills Narrows, and indeed to start serious lock rebuilding work at Codnor Park, there’s

Darren Shepherd

Starting point: looking north from the current limit of navigation at Langley Mill

another project that looks set to take priority - and as hinted at above, it’s the A610 crossing north of Langley Mill.

Christened the Beggarlee Project, this is set to be FCC’s main focus of work in the coming years - and has just gained planning permission after considerable delays. And getting under the canal under the A610 is going to be an interesting job...

Although the main road embankment blocked the route of the canal, it did include a bridge for a railway siding leading from the Midland Main Line eastwards to a nearby coal mine. Both pit and railway siding closed not long after the road was opened in 1983, leaving a nearly new but unused concrete span. It’s plenty big enough to fit a restored canal through it, but it’s at a slightly awkward angle and a completely different level - plus its foundations aren’t designed to support a canal channel. But even so, designing a canal diversion to use the former railway bridge will still be a lot easier, cheaper and quicker to achieve than trying to get a new canal bridge put in under the main road. So that’s been the idea for some time, the plans have been developed and submitted, and the latest news is that they’ve been approved and the work can go ahead.

The first part is straightforward: a 100 metre length of channel was built some years ago by ECPDA volunteers and awaits removal of the dam separating it from the limit page 14

of navigation at the north end of the Langley Mill basin complex. Beyond there the channel ends, trees and vegetation take over the route, and an embankment encraches from the right - this is a former slip-road now unused, and will need to be dug out to make way for the new canal.

In addition to the old channel having disappeared, two original locks have been lost: Lock 12 lies buried under what is now the A610 embankment, while Lock 11 was half a mile further north. So at this point a new pair of staircase locks will be built, to replace both of these locks , and also to bring the canal to a suitable height to pass under the A610 using the bridge which carried the former railway siding. As we mentioned above, it’s a bit of an awkward angle (the canal is heading northwards while the railway had more of an east-west route, so there will be a sharp right hand bend between the new locks and the bridge, then a sharp left-hander when the canal emerges from the bridge), and as we also mentioned its foundations weren’t designed to carry the weight of a canal filled with water, so the structure will actually be more akin to the canal being carried through the former railway span on a new aqueduct, supported from new foundations situated beyond the profile of the road embankment.

From there, the new channel will continue for another 500m to Stoney Lane,

Cromford Canal:

The Beggarlee Project

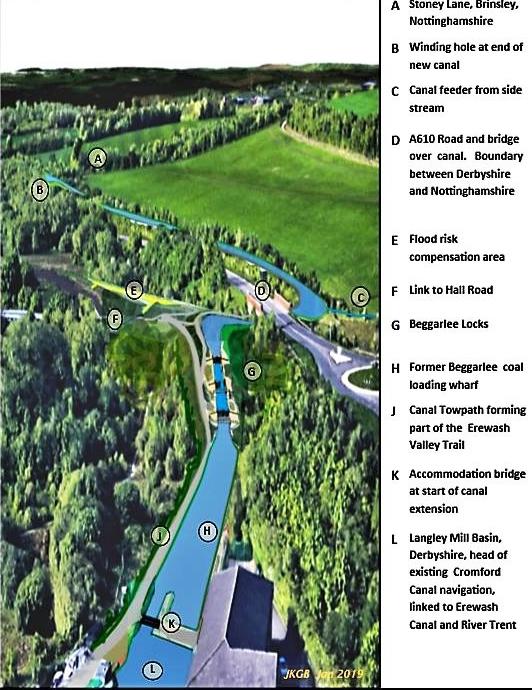

The above graphic, reproduced from the Friends of the Cromford Canal, shows the plan for the Beggarlee Project, looking north from the existing limit of navigation on the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill, towards the new staircase locks, the dog-leg to the east to pass through the old railway bridge under the A610, and the canal continuing to the new winding hole at Stoney Lane

where the initial section will terminate at a new winding hole (turning point).

OK, so it’s only about 1km in total, but this is a very significant length as the Friends’ first major construction project, it’s an actual extension of the national

navigable network, and it hopefully it will be seen as a real statement of intent to reopen the canal. And as far as WRG is concerned (as and when we get back on track following the current difficulties), it could be an important worksite for our volunteers. The locks are likely to be at least largely contractorbuilt and designed as an unashamedly modern conTwo views of the old railway bridge that is set to be converted into a canal bridge as part of the Beggarlee Project

crete construction (so no brick facings for us to add to the basic structure, as has been the case on some), and the railway bridge (being quite technically complex, as explained above) will probably also be a professional job. But creating the lengths of channel linking it all together looks much like our sort of work, as does the initial site clearance and earthworks.

For this reason, the job is likely to be split into three phases: (1) the channel as far as the locks, (2) the northernmost section of channel beyond the A610, and (3) the locks and bridge. Doing the work in this sequence means the volunteers can get on with the cheaper parts while fund-raising continues for the more expensive later stages. So look out for details in Navvies of volunteer work beginning in the not-too-distant...

And then what? It might seem obvious to simply carry on north, but the next length isn’t easy. Not only has the original channel (and locks) disappeared as a result of opencast mining, but a new crossing for Stoney Lane is needed, and not far north of there a new crossing of the valley - and there’s a nature reserve, so there will need to be careful discussions about whatever route is chosen. It seems more likely that FCC will look first to a project in the Ironville area, perhaps the first length of the Pinxton Arm –a relatively simple scheme but one in the heart of the community, to build local support and demonstrate a positive approach to environmental conservation. Sorry to all of you waiting at Langley Mill with your boats but canal restorations rarely get anywhere without gaining local support.

Ultimately, however, the aim is for full restoration through from Langley Mill to Cromford and Pinxton - and the Beggarlee Project will be a big step forward on the way. Martin Ludgate with assistance from George Rogers

To find out more or to join the Friends of the Cromford Canal see cromfordcanal.info