18 minute read

win’ projects - the Wendover, Stafford, Bradley and Pocklington canals

Restoration feature

As we once again use the reduction in WRG work to take a wider look at projects,

OK, some of you will already be looking at the word ‘quick’ above with raised eyebrows and thinking “Martin’s really lost it this time!” And yes, I’ll admit that as far as most canal restoration projects we work on are concerned, one word you wouldn’t use to describe the rate of progress is ‘quick’. Not that I’m knocking the restoration societies for it: obviously there are understandable reasons why canal restoration takes a long time these days. Quite apart from the fact that in practical terms we’re onto the ‘difficult’ schemes, canals that have suffered the level of damage and obstruction that you’d expect from having been abandoned for the best part of a century or more, there’s also the amount behind-the-scenes stuff (permissions etc) that needs to be done first these days, not to mention the potential costs running into eight figures for some of the longer and more difficult waterways - a tall order for any of the usual sources of funding.

Indeed, in the last issue we ran an article covering WRG’s parent body the Inland Waterways Association’s Waterways in Progress report and funding awards, whose aim is to address this issue. It does so by showing that even in the case of projects which are unlikely to be complete for decades, there are lots of ‘quick wins’ in the meantime – ways that canal restorations can be providing benefits right from day one with initially small-scale affordable projects (such as local regeneration schemes, towpath trails, nature reserves, linear parks and local trip-boat operations) which can attract support and at the same time bring the distant goal of full reopening gradually closer.

But this time we’re taking a different angle. Besides all these decades-long restorations costing tens of millions (and more) to complete, there are a significant number of smaller ones which could be achieved much more quickly and for much less money. Note: ‘could’. Again I’m not knocking them for not having got their canals open yet! There are many perfectly valid reasons why some of these schemes have taken (and may still take) a long time to finish – whether it’s the sheer amount of work involved in volunteers carrying out a complex channel rebuilding project over two miles long (as on the Wendover), long and difficult negotiations in the past over nature conservation issues (the Pocklington) or having to convince three different local authorities to support it (the Bradley Canal).

And note also that when I say ‘smaller’ I don’t just mean a shorter length of waterway. For example (a) the Lapal Canal and (b) the Lichfield Canal comprise no more than six miles of derelict waterway each, but include respectively (a) a two-mile tunnel that’s beyond repair so reopening clearly won’t be a straightforward job and (b) 30 derelict locks and enough obstructions that around five diversions will be needed. That’s not to say they won’t happen: they’re both making good progress, I wish them well and I will cover them in future issues.

No, I mean ones where the remaining obstacles to reopening are of the sort of size that means that they could be reopened relatively quickly and to the sort of budget that’s comparable to what we know has been made available for canal projects recently. Something not too far beyond the same ballpark as (for example) the £4m grant that Highways England paid to reinstate the Cotswold Canal’ crossing of the A38 dual carriageway, or the £9m Lottery grant announced last year for the same scheme (or whatever - fingers crossed - comes our way from any Covid-19 recovery funding grants) – especially if use of volunteers can help to bring the costs down to that sort of manageable size.

This doesn’t attempt to be an exhaustive list, or to lay down any standards for what might or might not qualify as ‘quick win’ schemes. I’m sure there are other examples that are equally valid that I’ve missed - feel free to point them out to me, or even better write a piece for Navvies about them.

But here are a selection of what might just be ‘quick win’ canal restoration projects...

possible ‘Quick win’ schemes?

we focus on schemes that it just might be possible to complete in the short term

Wendover Arm

The restoration back-story: Although abandoned as a navigation after all attempts to solve its leakage problems proved unsuccessful, the Wendover Arm of the Grand Union Canal was retained as an unnavigable feeder, which helped its survival and improved its prospects for restoration. It splits into three lengths: the first two miles from Bulbourne Junction to Tringford Pumping Station remained navigable; the next two miles from Tringford to Aston Clinton were drained (and a short section at Tringford was filled in) with the water supply carried in a pipe largely laid in a trench dug in the canal bed; the final three miles from Aston Clinton to Wendover were kept in water as a feeder but at a reduced water level.

Wendover Arm Trust, formed in 1989, began by rebuilding the first short length (referred to as Phase 1) from Tringford to the start of the infilled section, including reinstating Little Tring road bridge and creating a winding hole so full-length boats could turn round, greatly increasing use of the navigable length. This was completed and reopened in 2005. Since then the volunteers have been painstakingly rebuilding the much longer dry section (referred to as Phase 2) from Aston Clinton back towards Tringford, including excavating each section of the water pipe in the canal bed, capping it in concrete, then reinstating the canal above it as a waterproof channel combining concrete and a Bentomat waterproof liner. In addition, two footbridges have been built, an old pumping station site at Whitehouses has

Wendover Arm

Length: 6 miles Locks: 0 (1 stop-lock added) Date closed: 1904

Grand Union Main Line to Birmingham

The Wendover Arm has the dubious distinction of Marsworth

having been built as a navigable feeder to provide a Aylesbury Bulbourne

water supply to the Grand Arm Junction

Junction (now the Grand

Infilled section: Union) Canal, but ending Tringfordplanning under up leaking so much that it was way for dealing actually costing the canal water. To Londonwith contamination Attempts to waterproof it (including lining a section of it with bitumen) proved unsuccessful. A41 Little Tring In 1904 the canal company gave up, Bulbourne to closed it to navigation, drained the Aston Clinton Little Tring: length from Little Tring to Aston always Clinton (with the Arm’s water navigable supply function maintained Phase 2 Little Tring by carrying the water in a to Aston Clinton: Phase 1 at LittleHaltonpipe laid in a trench dug under restoration / Tring: in the former canal bed). channel rebuilding reopened 2005 From Aston Clinton to Wendover the remaining Phase 3 Aston Clinton Bridge 4 current length of the canal was to Wendover: work site maintained as an in water at reduced unnavigable water supply level, two new channel, with the water bridges needed Whitehouses former pumping station sitekept at a reduced level. Wendover

been restored, and mooring bays have been created - as the profile of the channel won’t be suitable for mooring everywhere.

Where are we at now? The Phase 2 rebuilding has reached most of the way back to Tringford, and work has just begun (see our Progress pages in this issue) on preparing to deal with the contaminated infill material, which will remove the other main obstruction to navigation on this length.

What’s left to do? Once the canal is restored to Aston Clinton, that leaves the three miles (‘Phase 3’) from there to Wendover which is still in water and shouldn’t need lining. There are two minor bridges (one carrying a small road near Halton) that do not provide navigable headroom and will need to be raised. Other than that, the main work will be raising the water by about 300mm to the original level (and dealing with leaks as they arise), and dredging the channel.

Stafford Riverway

The restoration back-story: Restoration of the mile-long Stafford Arm of the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal was first suggested in the 1970s, but it was another 30 years or so before discussions led to the setting up of a group aiming to reopen the route. This group was established as a Community Interest Company called the Stafford Riverway Link in 2009. In recent years they have progressed on to practical volunteer work, with good progress made on the first project to reinstate the short length of canal from the junction with the Staffs & Worcs Canal at Basford to the abutments of the former aqueduct over the River Sow. page 14

Wendover Arm: opening of Phase 1 length in 2005 and (below) a minor road bridge on the Phase 3 length needs raising

Stafford Riverway: the basin begins to take shape in 2019

Where are we at now? Work is continuing on the first length of canal, which is being rebuilt wider than original width so that it can form a mooring basin. This will mean that berths can be let out, providing an income to support further restoration work. In addition, planning consent has been granted for reinstatement of the bridge which carried the S&W Canal’s towpath over the junction with the Stafford Arm, which is necessary so that the connection can be reinstated, the moorings brought into use and ultimately the route to Stafford reopened.

What’s left to do? Changes to the River Penk Stafford Riverway: River Sow bridges already navigable sized and River Sow (and Environment Agency considerations) mean that the turn right into the Penk, then sharp left at waterway will not follow it original course: it the Penk’s confluence with the Sow. So the used to span the Penk via the aqueduct new lock needs to be built, but from then on mentioned above before descending through the navigation follows the existing river, one lock and turning left into the Sow; it will bridges all have navigable headroom, so the now instead drop down through a new lock main remaining tasks will be channel works leading from the mooring basin to the Penk, and creation of a terminus in Stafford.

Stafford Riverway

Length: 1 mile Locks: 1 Date closed: 1927 (last use)

Stafford Canalised River Sow from Baswich to Stafford Planned diversion including new lock and short length of River Penk

River Sow (unnavigable)

River Sow (unnavigable)

Proposed basin Site of old lock and aqueduct Basin under construction New lock site

Staffs & Worcs Canal To Great The Stafford Arm of the Staffordshire & River Penk

HaywoodTowpathWorcestershire Canal was opened in 1816 from a (unnavigable)

bridge to bejunction with the main line of the Staffs & Worcs at

To Stourport reinstated

Baswich to a terminus near Stafford Town Centre. It was unusual in a couple of ways: firstly it consisted largely of a one-mile length of the straightened and canalised River Sow, with the connection at Baswich consisting of a short canal section including the Arm’s only lock and an aqueduct over the Sow’s tributary the River Penk.And secondly it wasn’t officially a branch of the S&W, it was privately owned by landowner Lord Stafford. Trade on the Arm ended and the route fell into disuse around 1927, the junction had been blocked off by 1939, and in the 1970s the lock, the aqueduct and the towpath bridge at the junction were all demolished. page 15

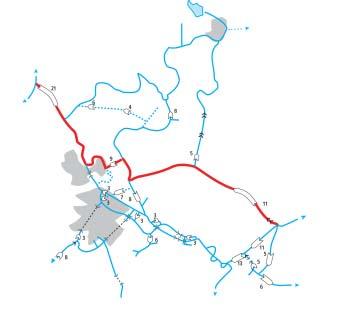

which would make it more accessible – and of these, the Bradley route is seen as by far The restoration back-story: The naviga- the best prospect for restoration as a result of ble waterways of the northern Birmingham the relative lack of obstruction (it’s largely filled Canal Navigations – such as the Walsall in but the land hasn’t been built on) coupled Canal; the surviving length of the Wyrley and with its short length at under 2 miles. Essington Canal; the Tame Valley Canal – are fascinating industrial Birmingham Canal Navigationsheritage and an asset to the Black Country but (as many who showing the new through go on the BCN Clean Up week- route across the network Lichfield ends will attest) are underused created by Bradley Canal under restorationand could do with more boats on Canal restoration them to avoid a vicious circle of Wyrley & Essington Daw Endlack of use, attracting rubbish, Canal Branchand becoming difficult to navi- Wolverhampton The de-gate. However they suffer from not being on a direct route to anywhere in particular, meaning that few boaters other than real hardened BCN enthusiasts will BCN main line Walsall Canal Walsall Rushall Canal tail map below shows the area in theventure there. Three former blue boxroutes - the Tipton Green & Toll Tame Valley End Communication, the Bradley Canal Canal (or Bradley Locks Branch) and the Bentley Canal - all abandoned in the 1950s-60s, used to provide links between the Walsall Canal and other routes to the west. Any one of these would be Dudley Canals BCN main line Birmingham useful today in creating through routes across the northern BCN

Bradley Canal Length: 2 miles Locks: 8 Date closed: 1954 Walsall Canal The Bradley Canal was built as fourWednesbury to Walsall separate sections of canal. FirstOak Loop to Bradley came the original BirminghamDeepfields lock gate Channel intact, Canal Main Line in 1772, thenJunction workshops clearance planned Moorcroft next to open was a shortand Wolver- Junction branch of the Walsallhampton Canal climbing through Canal infilled but four locks (later rebuilt not obstructed To Ryders Green as three) from and Birmingham Moorcroft Tramway Junction to New bridge needed Bradley Locks Bradley Hall Colliery. Third to open was the splendidly named Rotten Brunt Line, which cut off a loop of the Birmingham Canal (which was also subject to a much more major programme of shortenening, so that this whole length was bypassedRotten but survived as the Wednesbury Oak Loop).Brunt Line Locks buried but Finally in 1849 they were connected together bybelieved intact a short new link which included the upper six locks. Wednesbury Oak The entire Wednesbury Oak Loop, Rotten Brunt Line and Bradley Locks Loop to Tipton were officially abandoned in the 1950s but the northern part of the loop (abandoned) was kept open for access to the workshops and pumping station at Bradley page 16

from local MPs, the Canal & River Trust (for whom the restored link would provide a handy water feed channel from the Bradley mineshaft pumps to other parts of the system, quite apart from any direct navigation benefits), and the local authorities (things are made more complicated by there being three of them – Wolverhampton, Walsall and Sandwell – on the route). On the practical side, some years ago lock 8 was partly restored (but then filled Bradley Canal: The bottom two locks are infilled but still visible in with gravel for protection) thanks to a

The idea of reopening it was looked at Heritage Lottery Fund grant. Although other back in the 1990s, and a report was pro- than that the restoration hasn’t reached the duced, but the local authorities didn’t have point of major practical work on the infilled the cash to support it. Fast forward 20 years lenths, the watered and (in theory navigable) to 2014 and the idea was resurrected with but overgrown bottom section (leading from the BCN Society, IWA and the local wildlife the junction with the Walsall Canal to the trust all involved. This time Wolverhampton bottom lock No 9) was due to see vegetation Council showed showed interest in the idea, clearance early this year (including some so did the Canal & River Trust - and the possible work during the BCN Cleanup, sadly advice to those proposing the retoration was not now happening as a result of the new to get as much support as they could. lockdown). Meanwhile the Society continues

Where are we at now? There is now to campaign, raise awareness, and work to a group, the Bradley Canal Restoration Soci- build up support with the local community. ety, leading the restoration bid, and it has An environmental survey is under way, a succeeded in raising a great deal of support - feaibility study has identified that the navigable connection could be reinstated at a cost of around £7.5m – and volunteer work could bring this cost down. What’s left to do? The single major engineering job is to reinstate the missing road bridge just past the limit of navigation on the Wednesbury Oak Loop (by the Canal & River Trust’s Bradley lock gate workshops). If that can be done, the rest is much more straightforward. The next section of the Loop from Bradley WorkBradley Canal: Archive shot of the top lock before infilling shops as far as the junction page 17

with the Bradley Locks line will need digging Pocklington Canalout as it is infilled, but it runs through open public land with no obstructions. Turning left The restoration back-story: Back in the at the junction, the same is true of route late 1950s, a proposal by a water authority down the line of the locks – the chambers to fill the canal in with “some inoffensive will need to be uncovered (currently the site sludge” from a treatment plant prompted a of the flight is a grassy area with a footpath response from the Inland Waterways Assorunning along it, sloping downwards steeply ciation objecting to this obstruction of a every so often to indicate the site of each waterway which had fallen derelict but never lock) but they are believed to be basically in been officially closed. Some years later this good condition (other than one damaged initial interest led to the founding of the when a culvert was inserted) and needing refurbishment and regating rather than rebuilding.

Another road bridge crosses the tail of the seventh lock down from the junction; again it’s infilled but believed to be intact and restorable. The final two locks are more visible (one was restored a number of years ago and filled with gravel to protect it) and reopening should be straightforward, a railway bridge (now carrying the Midland Metrolink tramway) over the last lock provides navigable headroom, and completion of clearance (as already mentioned) will be needed on the final watered but overgrown length leading to the Walsall Canal. Pocklington Canal: Sandhill Lock awaits our attention

Pocklington Canal

Length: 9 miles Locks: 9 Date closed: 1932 (last use)

Gardham Lock Pocklington

Top Lock and Coates Lock restored but not yet in use

Canal Head

Giles

Lock Sandhill Lock Top Lock Silburn Lock

River Derwent to Stamford Bridge Restored and fully navigable from River Derwent to Bielby

Thornton Lock

Melbourne Walbut Lock Coates Lock

Bielby Sandhill, Giles and Silburn locks to be restored

Cottingwith Lock East Cottingwith

To Barmby and the River Ouse page 18

The Pocklington Canal was opened in 1818, running for nine miles and climbing through nine locks on its way from a junction with the Yorkshire Derwent river at Cottingwith to a terminus at Canal Head just outside Pocklington. It was moderately successful for 30 years, but in the 1840s, facing competition in the future from railways, the canal company sold out to a railway company. The canal remained open but with minimal maintenance, until trade eventually ended in 1932. Although not legally abandoned, it then fell into dereliction.

Pocklington Canal Amenity Society, launched in 1969 with the aim of reopening the canal.

Restoration began with reopening of Cottingwith Lock, opening up the first section from the River Derwent. This was followed by Gardham Lock, which brought boats to Melbourne in the 1980s, and then by four more lock - Thornton, Walbut, Coates and Top - in the 1980s-90s. However none of these locks saw any boats, and neither did any more lengths of canal, largely because the designation of the canal as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (and various other nature conservation designations) led to something of a standoff with wildlife interests concerned at the impact of boat on the canal’s sensitive biodiversity, and to no further reopenings for many years.

More recently better relations and a more helpful attitude from nature interests and the navigation authority, plus funding from a Lottery grant, IWA and a PCAS appeal, saw Thornton and Walbut locks refurbished and the canal reopened to Bielby in 2018.

Where are we at now? The canal is open from the Derwent for about seven miles via four locks to Bielby. In addition Coates Lock was restored some time ago, and the terminus basin at Canal Head has been renovated and rewatered including the restoration of the adjacent Top Lock.

What’s left to do? Of the canal’s nine locks, three (Silburn, Giles and Sandhill) remain to be restored (one of these is earmarked as a candidate for WRG support), while about two miles of channel from Bielby to Canal Head need to be dealt with.

So how quick is a ‘quick win’?

I’m afraid that if you want a prediction for some opening dates for these four potential ‘quick win’ schemes I’m going to have to disappoint you. Experience says that anyone predicting canal reopenings is liable to end up with egg on their face when they’re years later (or just occasionally when they’re years earlier!) than anyone expected. So I’m not going to stick my neck out and say that any of these will open in the next five or ten years, but at the same time I’m not going to go down the ‘not in my lifetime’ road and rule it out. All four of them could. And, as ever, volunteers (including WRG when we get going again) can help make it happen. Martin Ludgate