‘A surprising and brilliant volume that invites us to further engage with discussions about colonial empires and regional legacies through local communities, buildings, objects and arts.’

Olivette Otele, Distinguished Research Professor of the Legacies and Memories of Slavery, SOAS

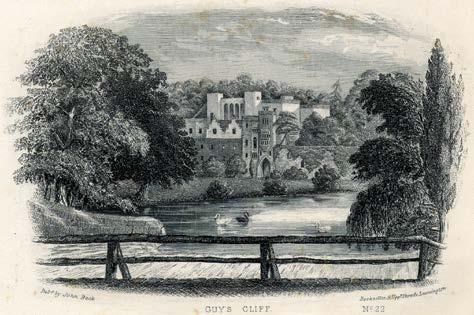

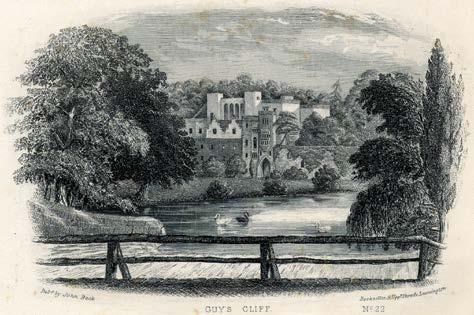

The cover illustration and inside back cover are based on photographs of the ‘Blackamoor Garden’ at Guy’s Cliffe, Warwick, from Country Life VII/162 (10 February 1900). The garden was laid out by Bertie Greatheed around 1810. See chapters 2 and 4

2

Acknowledgements

The editor gratefully acknowledges the support of the Social History Society.

This book was commissioned to accompany an exhibition at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, ‘“Built with malice aforethought”: Leamington Spa and the Black Atlantic’. Both the book and the exhibition draw on previous research by Ben Richardson, Vicki Slade and others, uncovering Leamington’s links with British colonies in the Caribbean. The exhibition narrative was also underpinned by new research undertaken by Jessica Nyassa, whose dedication to the project has been extraordinary. A community advisory panel of local Black historians was appointed to act as critical friends during the development process: Angela Allison, Holly Cooper, Annabelle Gilmore, and Ciara Winston, whose perspectives shaped our approach to the project and encouraged us to ask important questions.

Thanks are due to graphic designer Natasha King, who worked on both the book and the exhibition. Abigael Flack, Giovanni Vinti and other colleagues at Warwick District Council have also contributed their expertise and practical support to this project.

Lily Crowther April 2024

Content notice: this book describes violent and distressing histories of enslavement and racism. As the book includes quotes from original sources, please be aware that some of the historical language is offensive.

3

Contributors

Lily Crowther is a History Curator at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, where she curated the exhibition ‘“Built with malice aforethought”: Leamington Spa and the Black Atlantic’ (25 May – 15 September 2024). She is also working on a DPhil at the University of Oxford and the V&A, researching the history and legacies of the Museum of Construction & Building Materials, which was part of the South Kensington Museum in the 1850s-80s. She is a trustee of the Brooking Museum of Architectural Detail.

Charlotte Hammond is a Lecturer in French Studies at Cardiff University. She is the author of Entangled Otherness: Cross-Gender Fabrications in the Francophone Caribbean (Liverpool University Press, 2018). Hammond is passionate about public engagement and with Coleg Menai collaborated on a creative heritage project that explored colonial histories of woollen production in Wales. This resulted in the publication of a bilingual free ebook, Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery / Hanesion Cysylltiedig Gwlân Cymru a Chaethwasiaeth (Common Threads Press, 2023). She is currently writing a new book titled Material Mawonaj: Haitian Women Workers, Secondhand Clothing Cultures and Creative Mobilities in the Caribbean

Annabelle Gilmore is a PhD researcher at the University of Birmingham on a Collaborative Doctoral Award with the National Trust, funded by AHRC Midlands4Cities. Her thesis explores the hidden histories of art objects with links to imperialism and slavery, where she merges material and social histories. Annabelle focuses on studying the relationship between Caribbean and British histories; particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. She is currently assisting on a project for bringing together Black British histories.

Tobias Gardner is a second year History PhD candidate. He is in the peculiar position of simultaneously being someone who grew up in Sheffield, studies at the University of Sheffield, and has become a historian of Sheffield. His PhD research focuses on Sheffield's broad connections to Atlantic Slavery between 1750-1888, both in terms of industry and commerce, but also society and politics. He is committed to engaging academic research with a wide audience, and through his work has collaborated with various public organisations, including Sheffield City Archives, Museums, and the General Cemetery.

Jessica Nyassa is a historian with a passion for uncovering untold stories from history. After completing her undergraduate degree in History at the University of Warwick, she is currently undertaking an MA at UCL in Medieval and Renaissance History. Her areas of particular interest range from the Mali empire in the 14th century and global interconnectivity in the medieval period to the effects of slavery and colonialism on local British communities.

Dorcas Taylor has over 30 years’ experience of working in the museums and the wider cultural and learning sectors. She is currently Head of Collections and Interpretation at Scarborough Museums and Galleries. She has a particular interest in Cultural Rights and has been an independent advisor for the UN Special Rapporteur for Cultural Rights. She begins a PhD in Human Rights, with a focus on Intangible Cultural Rights, at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, in October 2024.

Tré Ventour-Griffiths is an award-winning multiply neurodivergent creative, public historian, sociologist, and cultural critic, who speaks and writes on subjects broadly contained within Black British history, neurodiversity, intersectionality, cultural criticism, and insurgent politics. For more on him, see https://linktr.ee/treventoured.

4

Contents Introduction

Local Stories, Global Resonance – Lily Crowther

Chapter 1:

Weaving Stories of Wales, Textiles and Slavery through Art –Charlotte Hammond

Chapter 2:

Beyond Warwickshire’s Country Houses – Annabelle Gilmore

Chapter 3:

Plantation Tools and Bowie Knives: Rethinking Sheffield’s Local Connections to Atlantic Slavery in the Nineteenth Century – Tobias Gardner

Chapter 4:

The Town that Slavery Built: Leamington Spa and the Proceeds of Enslavement – Jessica Nyassa

Chapter 5:

Owning the Past: Addressing Colonial Legacies with Communities from the Congo and Scarborough –Dorcas Taylor

Chapter 6:

Black Lives in the Stix: Caribbean Northants and Decentring ‘Black London’ on Screen, 1948-85 – Tré Ventour-Griffiths 6-10 11-20 21-26 27-35 36-42 43-52 53-63

5

Introduction: Local Stories, Global Resonance

Lily Crowther

This book ranges widely across time and place, from the valleys of north Wales in the eighteenth century, via the country estates and fashionable villas of Warwickshire and the steel mills of Victorian Sheffield, to the Edwardian seaside town of Scarborough and living memories of rural Northamptonshire. The contributors use a variety of research methods and sources, including archives and museum collections, community collaboration, oral history and autoethnography. This eclecticism exemplifies how histories of empire and colonialism are relevant to every aspect of British local history. Whilst the stories of Britain’s major ports and their connections to the transatlantic slave trade have become part of mainstream public discussion, many people remain unaware of the pervasive legacies of empire in their own cities, towns, and villages. Since the 1970s, historians have taken inspiration from Sven Lindqvist’s exhortation to ‘dig where you stand’,1 urging the importance of public participation in local history as a tool for social transformation. Whether we are working in museums, schools, universities or community groups, we can deepen our connections to global history by focusing on the local details.

This project began in 2018 with a proposal for an exhibition at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum exploring the town’s links with slavery. Following the hiatus of COVID-19, this became ‘Leamington Spa and the Black Atlantic’ (25 May – 15 September 2024), an exhibition with a broader scope covering the multiplicity of connections between the town and the Americas, the Caribbean and West Africa from the late 18th to the early 20th century. The term ‘Black Atlantic’ was coined by writers Robert Farris Thompson and Paul Gilroy to describe the cultures shared among people of the African diaspora as they confronted enslavement, empire and their after-effects.2 In this exhibition, the term is used to encompass the wide variety of personal, political, economic and cultural connections spanning the Atlantic as a result of enslavement and empire. The exhibition narrative was refined in collaboration with a small group of advisors who shared their academic and personal expertise: Angela Allison, Annabelle Gilmore, Holly Cooper, Jessica Nyassa, and Ciara Winston. As well as integrating new research by Jessica Nyassa on the enslavers who made Leamington their home (see Chapter 4), the project also drew on existing work by Vicki Slade and Ben Richardson on Leamington’s links to the Caribbean.3

As research progressed, it became clear that there was not one single chronological story of Leamington and the Atlantic world, but many interrelated stories. These include the town’s links with the Confederacy during the American Civil War, its popularity among Victorian retirees from the tropics, and the origins of the African collections at the Art Gallery & Museum, as well as the local investments made by sugar producers, cotton magnates, gun manufacturers, and their heirs. These stories are specific to Leamington, but similarly complex webs of connections link everywhere in Britain to places throughout the British empire and beyond.4 Using the overlapping narratives of the exhibition as a starting point, this book aims to provide inspiration to anyone exploring Black history or histories of colonialism in their own local area.

1Lindqvist, Sven, Dig Where You Stand, (London: Watkins Media, 2023 [1978]).

2Farris Thompson, Robert, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, (New York: Random House, 1983); Gilroy, Paul, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, (London: Verso, 1993).

3Slade, Vicki, and Richardson, Ben, ‘The Greatheeds: from Sugar Cane to Spa Water’, Richardson, Ben, ‘John Gladstone: Colonial Wealth Comes to Leamington’, Richardson, Ben, ‘Owen and Elizabeth Mary Pell: Leamington’s Antigua Sugar Planters’, Richardson, Ben, ‘Andrew Low II’, and Richardson, Ben, ‘Charles Dickens Dombey & Son’, in Chapter 2, ‘Colonial Linkages’, Global Leamington, (Leamington Spa: Shay Books for Leamington History Group, 2022).

6

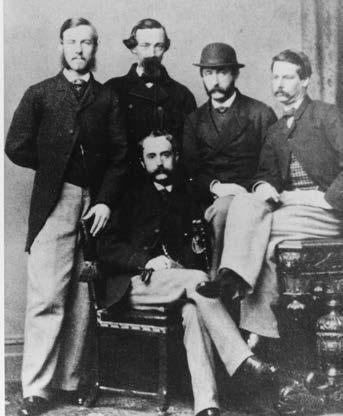

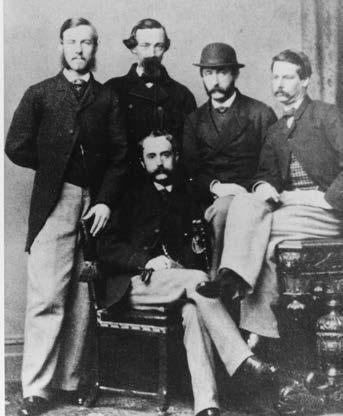

1. Mosianna Ruth Delegal and her husband, Tom Milledge, c.1880

Conspicuous luxury, concealed exploitation

The exhibition opens with an exploration of the luxury goods which defined the lifestyles of Leamington’s wealthy residents and visitors in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many such products, from sugar and mahogany to tortoiseshell, silver, and ivory, were produced by enslaved and exploited workers in British colonies and in the wider commercial empire. Objects such as tea services and miniature paintings are familiar tokens of the material world of the English upper classes, featuring regularly in museum displays and in the interior landscapes of stately homes. In contrast, the lives and experiences of enslaved people are almost invisible in Leamington’s museum collections, as they are in many heritage settings. This dichotomy is explored in the exhibition through the story of an extraordinary African-American woman, Mosianna Ruth Delegal (Figure 1). Delegal was enslaved in the household of cotton merchant Andrew Low, who moved back and forth between Georgia and Leamington. Delegal later worked for Low’s son as a cook, travelling with the family to Warwickshire in the 1880s. Here, she prepared their favourite Southern specialities and taught her recipes to their white British scullery-maid, Rosa Lewis. Lewis went on to become one of the most famous cooks in the country; she owned the Cavendish Hotel in London, where her signature Southern dishes were popular with the aristocracy, and their origins in Black Atlantic culture were erased.

Chapters 1 and 2 reflect this contrast between the moneyed lifestyles of the white upper classes, which are regularly rehearsed in popular historical narratives, and the stories of working people, which are often more difficult to uncover. In the opening chapter, Charlotte Hammond introduces a creative heritage engagement project exploring the historic manufacture of Welsh

4Other British museums have recently explored similar topics in relation to their local areas; for example, ‘Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance’ at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2022, and ‘Legacies of Slavery: Transatlantic Slavery and Aberdeen’ at Aberdeen University Museum, 2023 (available online at https://exhibitions.abdn.ac.uk/university-collections/exhibits/show/los/intro).

7

Figure

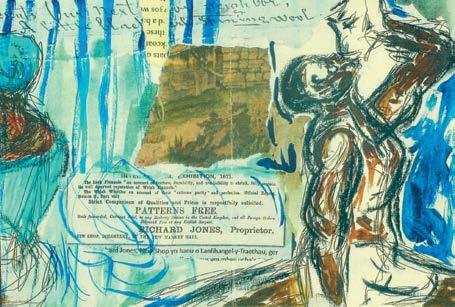

woollen textiles for use in clothing enslaved people in the Caribbean. This project involved collaboration between academics, community researchers, and art students. By bringing together deep understandings of the Welsh landscape and creative visual methods, the participants made hidden stories more tangible. Hammond discusses how this kind of approach can lead researchers to ‘embrace embodied and place-based ways of knowing.’ Meanwhile, Annabelle Gilmore reads between the lines of traditional archival sources to infer the presence and experience of Black people in the creation of the English country house. By reconsidering the materiality of stately homes and their contents in a wider context, she reinterprets these symbols of Englishness as the products and tools of empire. The layered histories which Gilmore reveals ‘are not at first obvious but become physically embodied in the houses and furnishings.’ Hammond and Gilmore thus both suggest ways in which creative engagement with place can recover stories which are otherwise at risk of being forgotten or erased.

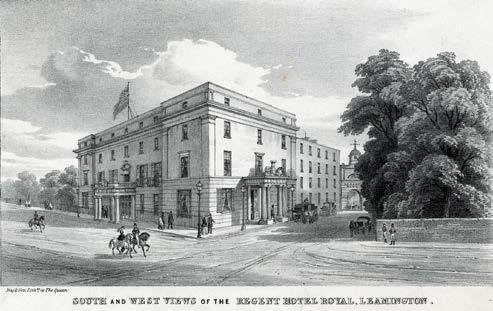

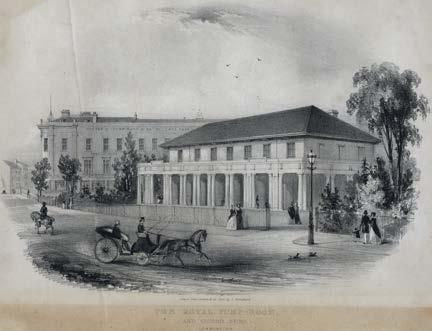

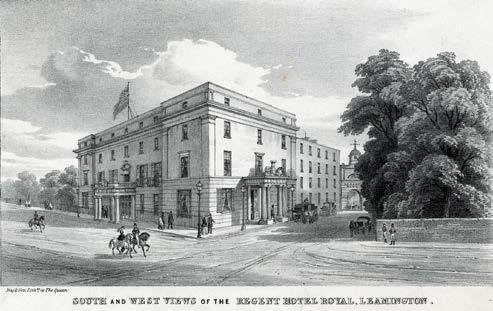

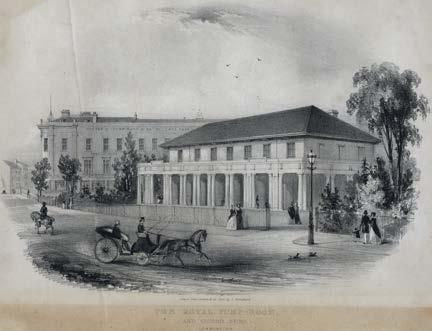

Extraction, export, and investment

The central stories in the exhibition reflect the changing townscape of Leamington in the nineteenth century and the varied relationships of local residents to the Atlantic world during this period. As a fashionable Regency spa town, Leamington grew rapidly from the 1810s onwards. Local landmarks such as the Royal Pump Rooms and Regent Hotel were built with fortunes made in the sugar trade and the supply of guns to West Africa. Many local residents received compensation when slavery was abolished in the British empire in 1838. During and after the American Civil War (1861-5), Leamington became a popular retreat for supporters of the Confederacy; visitors included Varina Davis, the wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and the crew of the CSS Shenandoah, who had fired the last shot of the war before surrendering in Liverpool (Figure 2). Leamington had a large population of Protestant nonconformists, providing a strong local support base for abolition, but there were still eager audiences for minstrel shows and other exploitative and racist forms of entertainment. Later in the nineteenth century, as the town became less fashionable and its grand villas grew more affordable, it was a popular retirement destination for those who had served in the military, the Foreign and Colonial Service, and as missionaries in the tropics.

Chapters 3 and 4 suggest how we can complicate and enrich our understanding of British towns and cities by examining the variety of ways in which they benefited from the vast wealth of empire. Tobias Gardner focuses on Sheffield, reflecting on the relative neglect of Britain’s great inland industrial cities in histories of colonialism, in favour of stories about trading centres such as Liverpool, Bristol and London. Whilst Sheffield has a proud and well-publicised history of abolitionism, Gardner uncovers its key role in the manufacture of tools for use by enslaved plantation labourers, and later the production of Bowie knives which were totemic of the pro-slavery American South. These economic ties led to widespread support for the Confederacy in the city; as in Leamington, these connections have largely been erased from public memory. Gardner points out that bringing such stories back into the popular narrative can ‘intervene within, and complicate, the prevailing view of post-abolition Britain as an empire that refashioned itself around antislavery ideals’. In her investigation of Leamington’s dependence on investments from the transatlantic slave economy, Jessica Nyassa also exposes a less familiar story – one which has been hidden behind more celebratory narratives which centre the town’s beauty and architectural heritage. Moving beyond a discussion of the landmark public buildings and grand houses built in Leamington using fortunes made in the Caribbean, Nyassa considers the ongoing local legacy of investment stemming from the compensation given to enslavers and their heirs after abolition. She also reflects on the enslaved people themselves, whose labour was stolen to enable all of this development, yet who ‘were listed in inventories and government records as nameless objects’. A full understanding of the impact of slavery and its persistence through the generations can support informed discussions of reparations in the present day.

8

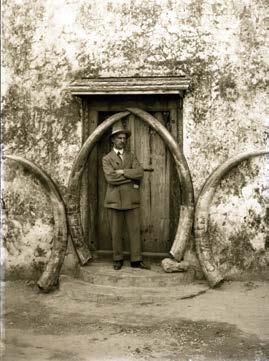

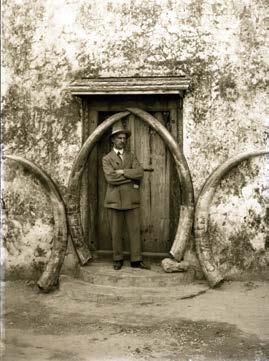

Figure 2. Confederate naval officers from the CSS Shenandoah in Leamington, 1865: Assistant Surgeon Edwin G. Booth (seated), and (standing, L-R) Sailing Master Irvine S. Bulloch, Passed Assistant Surgeon Bennett W. Green, First Lieutenant William H. Murdaugh, and Surgeon Charles E. Lining

Collections, communities, memories

The final section of the exhibition focuses on Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum’s collections of objects from West Africa, and their routes into the museum. New research has shed more light on three key donors: James Fenn Clark, Edward Carrington Holland, and Mary Ann Davies, all of whose stories illustrate the intricate webs of connections which brought artefacts from across the empire into British institutional collections. Fenn Clark was born in Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1823, where his father was a surgeon working for the East India Company. Educated in Leamington, he also grew up to become a doctor, and travelled extensively throughout his life. He was active with various Christian missionary organisations and was a keen collector. Like many of his contemporaries, Fenn Clark probably saw a link between these pursuits: he lent several objects to a Missionary Loan Exhibition in Birmingham where they would have served to illustrate theories of racial difference and to encourage public support for colonialism. Carrington Holland was likewise a child of empire, born in Haldummulla, Sri Lanka, in 1881, where his father was a civil servant. He spent part of his childhood in Leamington, near the home of his maternal uncle Edward Carrington. Carrington Holland collected extensively in West Africa around 1910, sending his collections back to his uncle for donation to the museum in Leamington. He went on to serve in the Australian Imperial Force during the First World War, and spent the rest of his life in Australia. Mary Ann Davies (née Parkes), by contrast, was born in Wolverhampton in 1848; she married her second husband, Rev. John H. Davies, in 1893, and accompanied him on a posting to Accra, Ghana. Following his death in 1911, Mrs Davies retired to Leamington, bringing with her an extraordinary variety of African objects (Figure 3). Although collectors’ motives are often impossible to establish, donating to civic museums was a way to assert social status as well as perpetuating certain views of empire and racial hierarchies.

9

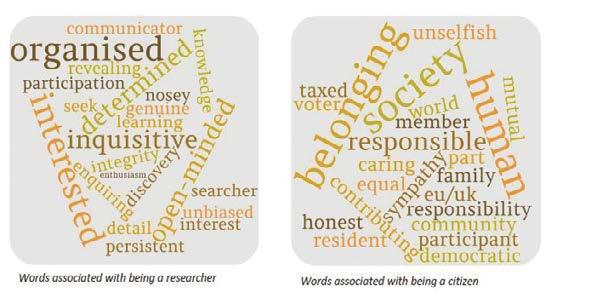

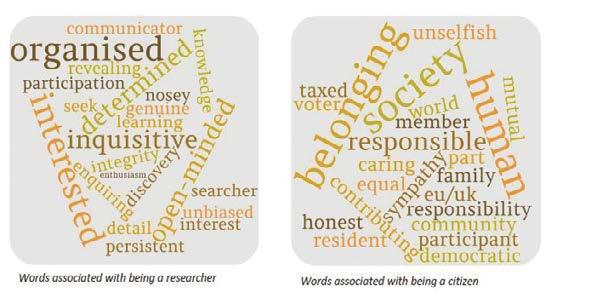

The legacies of colonial collecting are addressed by Dorcas Taylor in Chapter 5, which describes a project to reevaluate the Congolese collections held by Scarborough Museums and Galleries. Like many museums across Britain, Scarborough is beginning to grapple with the issues of decolonising in a sector fundamentally based on colonial structures. Their ambitious ‘Local to Global’ project aimed to use research into colonial history to ‘better understand the present and help us to avoid repeating mistakes of the past, not only benefitting museum practices, but also contributing to improvements within wider society’. Taylor describes how this process began with collaboration and conversation, both with the Congolese community in Yorkshire and with local ‘citizen researchers’ in Scarborough. Museums often present themselves as voices of authority, but by encouraging meaningful participation and granting agency to local communities in telling their own histories, they can open up other ways of knowing – an approach which Taylor explains is ‘both challenging and liberating.’ The importance of understanding and deploying local history to support a sense of belonging also underpins Tré Ventour-Griffiths’ argument in Chapter 6. This chapter questions why the regional diversity of the Black British experience is not reflected in the media, where a monolithic portrayal of inner-city life crowds out other viewpoints. Black people from the countryside or small towns do not see themselves, their heritage or their memories represented on screen, and the wider public is oblivious to their stories. VentourGriffiths points out the impact of sharing his work: ‘To see the place you call home written and talked about with same enthusiasm that broadcasters give Black London has brought belonging – both to white and Black people.’ Far from being divisive, a richer understanding of local history and of the experiences and memories of local people has the potential to bring communities together in genuinely collaborative ways.

10

Figure 3. Balafon, Sierra Leone, late 19th century. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum; given by Mary Ann Davies, 1915

Chapter 1

Weaving Stories of Wales, Textiles and Slavery through Art

Charlotte Hammond

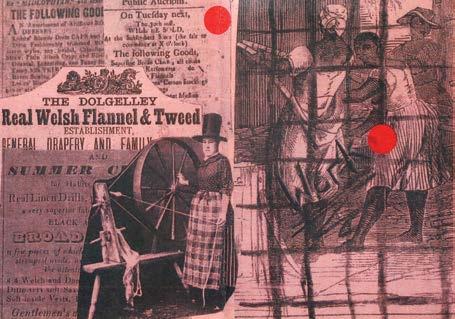

In recent years there has been increased scholarly research into the intimate ways Atlantic slavery and the slave trade is woven into Britain’s material culture and industrial heritage.1 Textiles, including woollens, cottons and linens, produced in Britain were important trade commodities in the system of Atlantic slavery and its plantation economies of the Americas. By the late seventeenth century, textiles accounted for half of all British exports to the Caribbean and nearly two-thirds of all goods exported to North America and Africa.2 This included mass exports of Britain’s staple woollens throughout the eighteenth century. In his vastly influential Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams writes that the cargo of a slavetrading ship was ‘incomplete without some woolen manufactures – serges, says, perpetuanos, arrangoes and bays’.3 Some of these woollen textiles, as Williams indicates, were named after the place where they were produced. ‘Welsh Plains’, a durable woollen cloth that was woven in mid- and north Wales between 1650-1850 competed for the colonial market alongside Yorkshire ‘Penistones’ and ‘Kendal Cottons.’ Until the abolition of slavery in the British colonies in 1833 and the development of the cotton industry during the Industrial Revolution, wool remained the most important of Britain’s textile industries. Despite the centrality of the Atlantic market for the woollen industry, the colonial history of Britain’s woollen goods has remained underexplored. There is a lack of public knowledge of how local histories of woollen production in Britain are deeply embedded in broader global histories of Atlantic slavery, racial violence and empire.

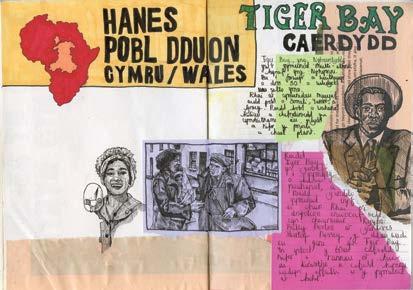

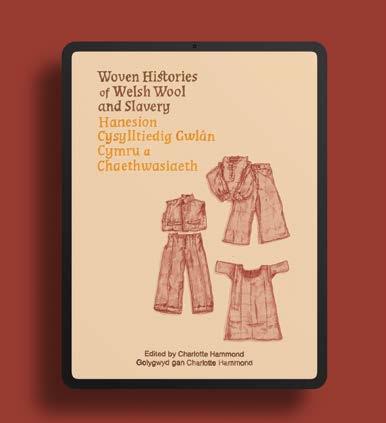

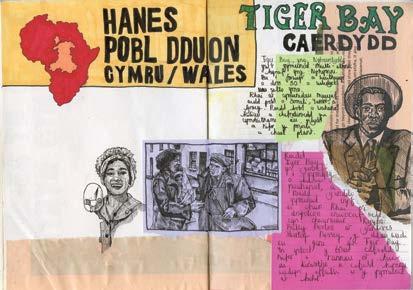

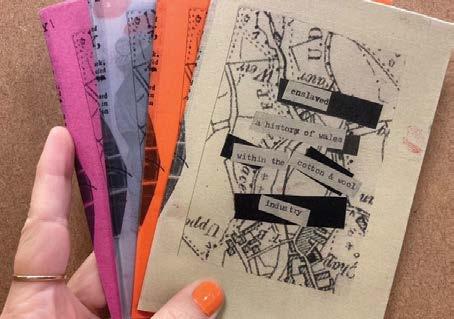

This essay reflects on a recent creative heritage public engagement project titled Hanesion Cysylltiedig Gwlân Cymru a Chaethwasiaeth / Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery. A partnership between Cardiff University, community researchers of Black Heritage Walks Network, Learning Links International, and Art and Design students at Coleg Menai, the project culminated in a bilingual Welsh/English open-access multimedia ebook (with interviews, essays and original artwork) of the same name published in June 2023 by Common Threads Press (Figure 1.1).4 The book, translated into Welsh by Elin Meek, provides an introduction to the local histories of woollen production in Wales and their connections to Britain’s transatlantic slave trade and empire. In this chapter I consider how the unique context in Wales, in particular its commitment and action plan to achieve an anti-racist Wales by 2030, has shaped the project design and delivery. I will reflect on what I have learnt from nonacademic partners during this project and how transgenerational collaboration between universities, community researchers and young artists challenges the oft-held assumption that local communities are opposed to addressing difficult colonial histories. I will also reflect on the creative process itself and how visual language (including illustration, zine-making and collage) can speak the unspeakable traumatic history of Britain’s transatlantic slave trade and contribute to alternative knowledge production.

1Evans, Chris, Slave Wales: The Welsh and Atlantic Slavery 1660-1850, (University of Wales Press, 2010); Riello, Giorgio, Cotton: the Fabric that Made the Modern World, (Cambridge University Press, 2013); Duplessis, Robert S., The Material Atlantic: Clothing, Commerce, and Colonization in the Atlantic World, 1650, (Cambridge University Press, 2016); Petley Christer and Stephan Lenik (eds.), Material Cultures of Slavery and Abolition in the British Caribbean, (London: Routledge, 2017).

2Berg, Maxine and Pat Hudson, Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution, (London: Polity Press, 2023), p.141.

3Williams, Eric, Capitalism and Slavery, (Penguin Classics, 2022 [1944]), p.60.

4Hanesion Cysylltiedig Gwlân Cymru a Chaethwasiaeth / Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery, (Common Threads Press, 2023) https://www.commonthreadspress.co.uk/products/woven-histories-of-welsh-wool-and-slavery

11

Figure 1.1. The cover of the ebook Hanesion Cysylltiedig Gwlân Cymru a Chaethwasiaeth / Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery, Common Threads Press, 2023.

Figure 1.2 Illustration by Chloe Buckless

12

Hanesion Cysylltiedig/ Woven Histories aimed to improve public knowledge of the colonial history of woollen production in Wales. Having made initial contact with Miranda Meilleur, course leader of the Foundation Degree programme in Graphic Design and Illustration at Coleg Menai, in the Spring of 2022, Marcia Dunkley of Black Heritage Walks Network and I began this taith/journey with an initial knowledge exchange day in Bangor. The participating students were a group of culturally, racially, and neuro diverse women artists. Together we explored historical sources, existing scholarship and the group’s evolving artistic practice. Through visual creative research methods, the students explored traces of a historical narrative that links the exploitation of weavers in rural Wales with the racial injustices of Atlantic slavery, and its reliance on the circulation of Welsh-made textiles (Figure 1.2).

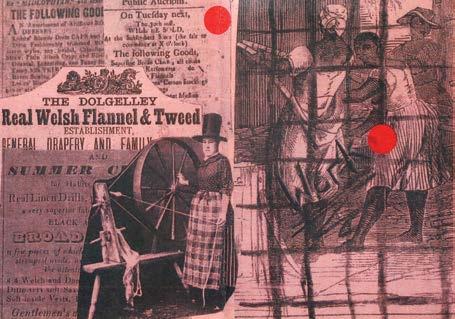

Assembling the Fragments

A poor-quality woven cloth, which was known collectively as “Negro” or “Slave cloth” in the eighteenth century, has in recent years provoked some interest from textile historians and researchers. In relation to Welsh plains, in particular, work by Chris Evans and Marian Gwyn has been instrumental in advancing knowledge within academic contexts.5 Beyond academia, since 2018, Grwp yr Aran, a group of community archivists and researchers based in Dolgellau in midWales, led by retired town archivist Mervyn Wyn Tomos and local mayor Ywain Myfyr, has been researching and preserving the history of the town’s woollen industry.6 Dolgellau, at the southern end of Eryri/Snowdonia National Park, became a centre for wool production, particularly in the late eighteenth century. Grwp yr Aran has focused on how Welsh plains were produced in the local pandai that line the Aran river in the town. The pandai were fulling mills where the woven cloth would be finished to clean, tighten and thicken the fibres. In 2019, community researcher, Liz Millman, led the 2019 National Lottery Heritage-funded project ‘From Sheep to Sugar’ which aimed to understand the whole process of how the cloth was made, how it was used in the transatlantic slave trade and on plantations in the Americas.7 The ‘Sheep to Sugar’ project worked with the spinners’, weavers’, and dyers’ guilds who attempted to recreate Welsh plains drawing on their accrued knowledge of the historical techniques of its manufacture, including the fulling process. As weaver Jill David explained, this was an early experiment to see if they could produce a cloth using methods and equipment as close to that available to Welsh hill farmers at that time. David points out that the variety of fleece used in their recreation was Clun Forest, a sheep bred for spinners and thus kept in less harsh conditions, producing a softer wool. This accounts for the result, which was a lighter woven fabric than the heavier denser textures described in historical sources and rare samples.

5Evans, Chris, Slave Wales: The Welsh and Atlantic Slavery 1660-1850, (University of Wales Press, 2010); Gwyn, Marian, ‘Merioneth Wool and the Atlantic Slave Trade’, Journal of the Merioneth Historical and Record Society, 18:3 (2020), 284-298.

6Tomos, Mervyn Wyn, Dolgellau: Diwydiant a Masnach/Industry and Commerce, (Nereus, 2018).

7‘From Sheep to Sugar’ (2019), see http://www.welshplains.cymru/

13

This community-based work led the group to trace a small sample of Penistone woollen cloth, handwoven on the Pennine moors. The swatch had been sent to British planter, William Fitzherbert, who went on to purchase 410 yards of the material to clothe enslaved people held at Turner’s Hall plantation in Barbados. Hand weaver Jo Andrews, who records the Haptic and Hue podcast, travelled to Derbyshire Public Record Office to examine the sample. The small swatch is dyed in indigo, which could have been grown in the Caribbean, where the French trade in particular dominated in the eighteenth century, and exported via Jamaica or Barbados. The tiny disintegrating fragment of blue cloth masks the violent process of its production and the humiliating conditions of its use on plantations in the Americas. In October 2023 the cloth was displayed as part of the British Textile Biennial at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery. The installation and light projection by Illuminos and Made by Mason allowed exhibition visitors to read the label on the reverse of the sample:

‘Penistone sent for Negro Clothing 1783 which for substance strength and unchangeable colour, is best adapted to that purpose.’

This inscription reveals how woollen cloth spun and woven in rural cottages and outhouses of Yorkshire tells the story of Britain’s economic, geopolitical and racial domination in its former Caribbean colonies. It is a tiny sample, a taster, woven out of threads that when unravelled, reveal how Britain’s regional woollen industries in Yorkshire, but also Cumbria and Wales, were bound up in systems of oppression and racial capitalism in the Americas.

Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery in ‘Woke Wales’

In a recent article in The Telegraph, Wales has been described as the ‘wokest country in Europe’.8 This is due to the development of its inclusive new school curriculum and its commitment to achieving an anti-racist Wales by 2030. In the wake of the Windrush scandal, Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd and a Covid pandemic disproportionately affecting the health of individuals from racialised minorities, compounded by pre-existing racial and socio-economic disparities, the Welsh Government acknowledged an urgent need for action. In March 2021 the Welsh Government and Race Council Cymru published their Race Equality Action Plan for Wales based on eight months of evidence collecting. This was the first time there had been an acknowledgement of institutional racism in any part of the UK. In the same month, the UK government published the highly controversial ‘Sewell report’ which investigated racial and ethnic disparities in the UK. The UK report rejected the idea of institutional racism in the opening pages and demonstrated a commitment to changing the narrative of race in British discourse away from victimhood and towards a celebration of progress. In contrast to Boris Johnson’s pro-Brexit conservative government in England, the Welsh Labour-led government in Wales, has been relatively proactive in recent debates over contested heritage, and calls for change in how Britain remembers its colonial past. In July 2020, following a month of BLM action, the then First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, acknowledged that:

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought to the fore a number of important issues we need to address as a country. One is the need for Wales to reflect on the visible reminders of the country’s past. This is especially true when we look at the horrors of the slave trade.

14

8Harris, Tom, ‘Labour has made Wales the Wokest Country in Europe’, The Telegraph, 17 March 2023. Researchers at Swansea University organised a conference on this theme, From and For Wales, in January 2024.

In July 2020, the Welsh Government launched a task and finish group, chaired by advocate for racialised communities Gaynor Legall, to undertake a review of public monuments, street and building names in Wales associated with the slave trade and the British empire. The group’s findings were published as ‘The Slave Trade and the British Empire: an Audit of Commemoration in Wales.’9 The report, however, does not document any sites or key figures related to Wales’ woollen industry. While the Coleg Menai students used these reports and scholarship in this area as a starting point for their research,10 through their visits to key sites and ruins, the students moved away from knowledge stored in this way to embrace embodied and place-based ways of knowing.

Stories of the Land, Stories of the Sea

Over the summer of 2022, Coleg Menai students began researching local stories of wool production. They organised site visits, walks, museum trips and began drawing visual cues to Wales’ colonial history of woollen manufacture. Their work visualises and assembles fragments: from the ruins of pandai fulling mills in Dolgellau, Meirionnydd, which became an important centre of wool production, particularly in the late eighteenth century, via the packhorse trails that transported Welsh Plains cloth to England. There, it was dyed and finished in Shrewsbury, then sent to London and Liverpool to be traded and then exported to the Americas (Aiken 1797).11 The students follow the cloth’s colonial connections to the Caribbean and southern states of the US. In their embodied research, walking, drawing and unfolding the hidden textures of this past within the local landscape, these artists have speculated and imagined meeting points between these different worlds, between the rural Welsh weaver exploited by English landlords and merchants and the oppression of plantation fieldworkers clothed in imported Welsh cloth, who themselves were reduced to disposable merchandise in a capitalist slave system.

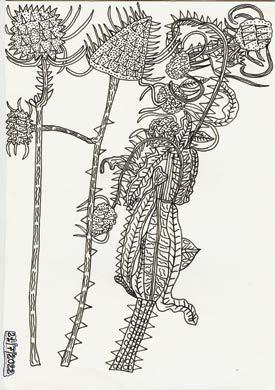

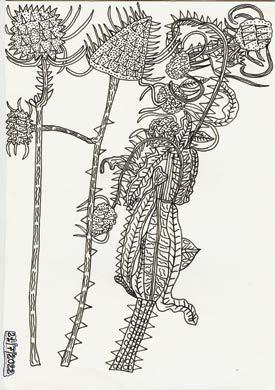

The students sketched local natural elements: from individual teasel stems (llysiau’r cribwr in Welsh which translates literally as ‘the carder’s vegetable’), traditionally used for hand carding and combing the surface of the wool (Figure 1.3), to the rivers and mountain streams that provided the water power for the pandai, where the woven cloth was washed, pounded and strengthened. They documented different breeds of sheep, the process of cneifio or sheepshearing and the raw material itself, wool. They drew man-made artefacts and sites connected to Welsh industrial heritage, including fulling mill channels, Shrewsbury Old Market Hall, where the Drapers Company sold on the wool to the London market, tenter frames, used to stretch out the wool in the fields, and old maps of Dolgellau. Using their historical research, they depicted instruments of violent oppression fabricated on colonial plantations: shackles, chains, branding irons, but also enslaved fieldworkers themselves who experienced these brutally harsh and dehumanising conditions. The students imagined the captives’ daily lives, acts of resistance, and the clothing enslaved people were forced to wear, made of Welsh plains.

9The Slave Trade and the British Empire: an Audit of Commemoration in Wales https://www.gov.wales/slave-trade-and-british-empire-audit-commemoration-wales 10Chetty, Darren, Greg Muse, Hannan Issa, Iestyn Tyne, Welsh [Plural]: Essays on the Future of Wales. (London: Repeater, 2022); Evans, Chris, Slave Wales: The Welsh and Atlantic Slavery 1660-1850, (University of Wales Press, 2010). 11Aiken, Arthur, Journal of a tour through North Wales and part of Shropshire, (London, 1797).

15

16

Figure 1.3 Illustration by Seren Haf Williams-Davies

Figure 1.4 Illustration by Elin Roberts

Figure 1.5 Illustration by Elin Angharad

Transgenerational Knowledge Exchange

In-depth discussions with friends, families and project partners enabled a transgenerational and transcultural approach to learning about this history. For example, the technical insight of Liz Millman, and the Brethyn Research network, many of whom are makers themselves, filled a knowledge gap through the work they were doing on the ground to understand the cloth’s process of production. Listening and learning from community group Grwp yr Aran and their ongoing work with Eryri National Park in Dolgellau to preserve the local industrial heritage of the town inspired place-based ways of knowing and highlighted the significance of the landscape and the memories that it holds. During our collaboration to deliver woolthemed workshops for local school Ysgol Bro Idris in July 2022, the group spoke about the centrality of the river Aran, memories of playing in the river, and the seeming insignificance of the pandai ruins, often thought to be just a pile of stones.

Ongoing conversations between the students and Marcia Dunkley on the incompleteness of localised Black history and how it relates to broader questions of racial injustice, British industry and empire inspired a critical enquiry and curiosity to question silences in the current education system. Our project was guided by what sociologist Alison Phipps calls ‘the experts by experience, where experience is often carried through generations, [and who] have much that is stored in the scars and the skin’.12 For Phipps, these ways of knowing mean taking a journey away from books and firewall-protected double-blind peerreviewed articles in top-ranked journals. As Haitian historian and anthropologist, MichelRolph Trouillot writes in Silencing the Past: ‘We are all amateur historians . . . Universities and university presses are not the only loci of production of the historical narrative.’13 This journey was not intended as extractive data collection, but instead sought to enable multidirectional learning. From the art students, I learnt about innovative ways of presenting this narrative and how it could be rendered more accessible to audiences. These ranged from DIY zines with the potential to infiltrate unexpected spaces and reach unwitting hands to the connections the artists drew via these visual histories, situating Welsh Plains in the context of wider Black histories in Wales. For example, Elin Roberts connected a long history of migration into Wales and Caribbean elders now known as the Windrush Generation Cymru, to the social and racial inequalities of a global textile industry controlled by European slavery. These arts-based responses and connections begin to theorise history in new, engaging and more inclusive ways, which raises questions about the role of the artist in narrating history (Figures 1.4, 1.5).

12Phipps, Alison, Decolonising Multilingualism: Struggles to Decreate, (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2019).

13Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995).

17

Zine-making, Creative Reassembly and the Artist

In the current era of global reckoning with colonial histories of enslavement, racial violence and oppression, how do we make space for collective remembering of the central role of slavery in Britain and Wales’ history? How do communities make spaces not only for education but also for healing? During this project, visual art offered a way of working through and walking with traumatic histories which are so often sidelined and remain unspoken. Beyond official archives, these place-based visual and graphic responses are a means of animating existing historical analysis and enhancing understanding of this history. Perhaps more powerful is their ability to offer a space for creative imaginary: to see, create and imagine other worlds.

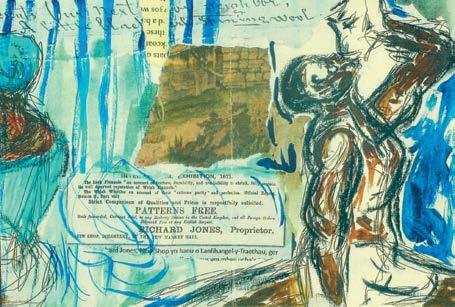

Given that many of the historical sources are written from the heavily biased perspective of the white oppressor14 and that very few samples of woollen fabric from this period have survived, the students’ speculative visions of life in Wales and the Atlantic world offer new narratives of archival material. The craft of speculation – a visual term deployed in the creative non-fiction of remarkable thinkers such as Hazel Carby and Saidiya Hartman – is for Carby a tool of unachieved emancipation.15 In British history today where the role of slavery in building the wealth and industry of the nation has been concealed, and the focus on celebrating white abolitionism has erased Britain’s collusion in slavery, the capacity of the artist to imagine a complex history of slavery’s entanglements, a people’s history that fills in the gaps through drawing and making, becomes even more important.

As Anne Butler, an artist involved in the project, reflected:

It was fascinating to find out the connection between these old forgotten mills, many of which are now being reclaimed by nature, and their part in the production of wool that was used to clothe enslaved people across the Atlantic. I think it is important to shed light on this history. The project brought up some strong feelings which could be channelled into our art.

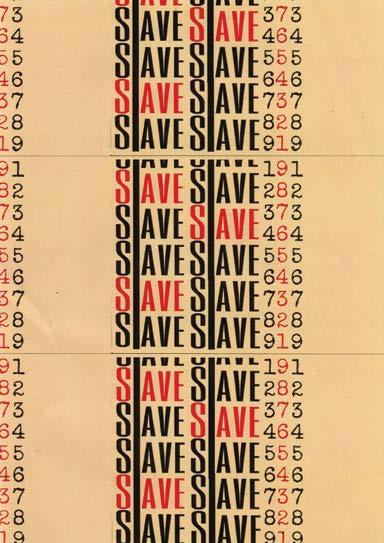

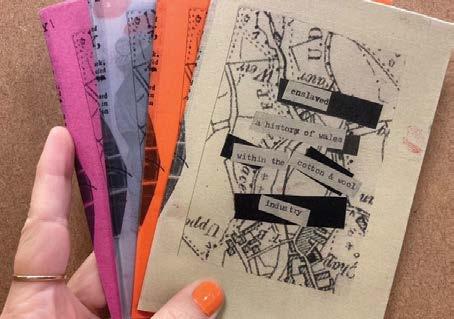

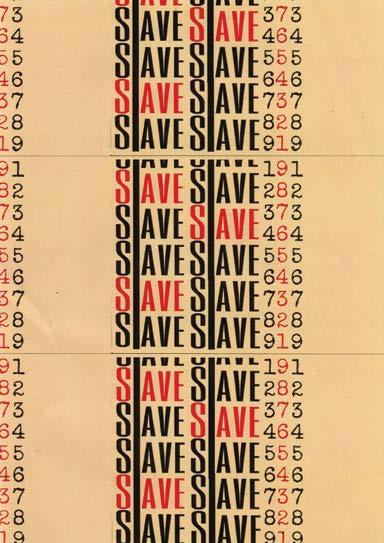

Zine-making lends itself to telling these counter-stories as a creative and inclusive form of alternative media. Zines are low-fi handmade booklets that offer perspective on a specific topic or theme. As part of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Festival of Social Sciences and in collaboration with Elin Angharad of Zine Cymru we organised a zine-making workshop as part of the Woven Histories project. The zine as an alternative pedagogical form offered a blank canvas to cut, collage and reassemble stories that connect the history of Welsh woollens to transatlantic slavery. The zines produced by participants reclaimed diverse printed material from the archives to reframe the dominant narrative of mill or plantation scenes authored by European travellers (Figures 1.6, 1.7, 1.8).

18

14Aiken, Journal of a tour through North Wales and part of Shropshire; Pennant, Thomas, A Tour in Wales, vol.I., (London: printed for Benjamin White, 1784).

15Carby, Hazel V., public lecture: “Imperial Sexual Economies: Enslaved and Free Women of Color on a Jamaican Coffee Plantation, 1800-1834” (University of Warwick, 4 Feb 2021).

19

Figure 1.6 Zines. Photo by Elin Angharad

Figure 1.7 Zine by Cushla Luxton

Figure 1.8 Zine by Deio Williams

As a starting point to the workshop we used the theme of marronage. From very early on, when African captives were transported to the Americas, they began escaping their European captors. Some joined Indigenous people, others set up their own communities in woods, forests, or mountainous areas to establish their settlements. By framing the workshop from the perspective of enslaved people escaping the constraints of the plantation and forming alternative communities on the margins, we were able to integrate ideas of freedom, reflect on creativity at the periphery of the plantation and foreground the humanity of enslaved men, women and children. Artistic methodologies such as zine-making offer a form of alternative media with the potential to intervene in educational spaces that have traditionally constrained certain forms of knowledge and bodies.16 Using the concept of zine-making as a modern-day form of reassembly or marronage – a collective effort to revise and enable a more comprehensive public understanding of the history of the transatlantic slave trade – the students used creative research methods, drawing, cutting, collaging image, text and textile to assemble new narratives.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, an important next step will be to investigate Welsh Plains from a Caribbean perspective and reorient this global history away from a uniquely Euro-American perspective. In Wales, further work with Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales is needed to include these global colonial narratives of woollen production and use within Welsh history. For example, the history of Welsh plains has remained largely neglected within Amgueddfa Wlân Cymru –National Wool Museum in Carmarthenshire, as well as some of Wales’ smaller regional museums including Newtown Textile Museum, Amgueddfa Llangollen or Amgueddfa Corwen that already tell local stories of wool production in these areas.17

To conclude this short essay, I want to reflect on a question I was asked recently following a presentation on this project at Swansea University. A researcher in the audience asked whether the participating students saw the project as a form of protest. By default I wanted to answer yes and feebly gave some of the ways the students have gone on to develop their research, yet this question made me pause. One example I could invoke is that during the zine-making workshop I had attempted to provoke discussion around the use of language and in particular the use of ‘slave’ vs. some preferred options including ‘enslaved person’, ‘enslaved African’ or ‘captive.’ One of the students shared that they outright refused to use any of these terms. This for me was a sudden moment of protest. In their justification the student seemed to be rejecting the terminology of categorisation systems associated with the colonial archive, many of which remain with us today. It challenged me as an educator to rethink my binary approach to teaching this and was a helpful reminder that there is not one singular narrative or one singular academic who knows everything.

The book Hanesion Cysylltiedig Gwlân Cymru a Chaethwasiaeth / Woven Histories of Welsh Wool and Slavery (2023) can be downloaded for free from Common Threads Press: https://www.commonthreadspress.co.uk/products/woven-histories-of-welsh-wool-and-slavery

16BARC Collective, ‘Zine-making for Anti-Racist Learning and Action’, in Suhraiya Jivraj and Dave Thomas (eds.) Towards Decolonising the University (Oxford: Counterpress, 2020).

17Cardiff-based artist Lucille Junkere has been commissioned to work with Amgueddfa Wlân Cymru – National Wool Museum in 2024 to create work that addresses the colonial connections of Welsh woollen production.

20

Chapter 2

Beyond Warwickshire’s Country Houses

Annabelle Gilmore

The country house has for a long time been seen as a symbol of Britishness, particularly Englishness. They have been features dotting the green landscape of the countryside since the medieval era of manor houses which were often relatively humble places for the lord of the estate, without the large scale of rooms and opulence thought of today.1 However, country houses did not remain as simply places for the lord of the manor to reside. The land ownership that was afforded to these lords saw the development of country houses as seats of power with money raised from the tenants and rents of the land. The properties became symbols for the owners; as ‘an image-maker, which projected an aura of glamour, mystery or success’.2 These buildings grew to encapsulate wealth and artistry, expectations and ambitions of the upper reaches of British society. Until the nineteenth century, landowners were the leading figures of the country. The people with money and ambitions made sure to invest in country estates.3 Land ownership was one of the few investments available before the development of industry in the nineteenth century. Except, many of these country houses have histories that go beyond the borders of the British Isles.

A great many houses have connections to the Atlantic world - the Americas, the Caribbean, and Africa - established through mercantilism, and governance. One of these methods of investment came in the form of overseas trading, which secured enormous profits, including the capture and transportation of African people. With these cash profits, aristocrats, gentry and merchants were able to invest and purchase lands in the English provinces.4 The country house may be a symbol of Britishness but it also carries legacies of enslavement of Black people. This essay considers some of these legacies in Warwickshire and beyond to connect these histories to the Black Atlantic, to think about the many Black people who are connected to these houses, and to open up ideas that country houses are more than the buildings and the land they sit on.5

Institutions such as English Heritage and the National Trust have already shown some of these histories and legacies for the properties they manage.6 They have highlighted the pervasive way that slavery can feature in the history of country houses. One example is Coughton Court (Figure 2.1), a property near Alcester in South Warwickshire managed by the National Trust. The Trust lists a connection between the house and plantation slavery through the marriage of Robert Throckmorton, 4th Baronet, and Lucy Heywood.7 Lucy’s father held the Heywood Hall Estate in St Mary, Jamaica, which enslaved over two hundred people. In his will dated 1738, Lucy’s father left her £3000 upon reaching twenty-one and Lucy’s mother an annuity of £700 to be paid for from the money from the Jamaican estates.8 In her mother’s will, dated 1755, Lucy was left a further £1000 upon reaching the age of twenty-one or upon her marriage.9

1Bailey, Mark, ‘The composition and origins of the manor’, in The English manor c.1200–c.1500, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), p.3.

2Mark Girouard, Life in the English Country House: A Social and architectural history, introduced by Simon Jenkins (London: Folio Society, 2019), p.4.

3Girouard, Life in the English Country House, p.4.

4Imtiaz Habib, Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677, (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), p.194.

5For further information on the Black Atlantic see Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993).

6Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann, Slavery and the British Country House, (Swindon: English Heritage, 2013); Sally-Anne Huxtable et. al (eds.), Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery, (Swindon: National Trust, 2020).

7Huxtable et. al. Interim Report, p.82.

8Will of John Heywood PROB 11/693/15.

9Will of Mary Heywood PROB 11/814/214.

21

22

Figure 2.1. Coughton Court © National Trust Images/Abi Chandler

Figure 2.2. ‘Guy’s Cliff’, published by J. Beck, 18491876. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum

Lucy, in her mid to late twenties, married Robert eight years after her mother’s death. It is possible that some of this money from the Heywood family plantations may have financially assisted Robert in building Buckland House in Oxfordshire and the renovation of the west front of Coughton Court. Lucy’s marriage settlement, dated 1764, shows that Lucy was to receive an annual payment of £400. In exchange, Robert Throckmorton received a lump sum of £3000.10 The settlement was orchestrated between Robert and Lucy’s brother, James Modyford Heywood, who had inherited the Jamaican estates and the enslaved people who worked the land. It is quite likely that the settlement money would have been arranged from the profits of sugar from these estates. It was necessary for a country house, as a symbol for taste and wealth, to be maintained in the latest fashions. Through marriage, Robert Throckmorton may have readily accepted the lump sum of money originating from plantation slavery, to maintain the symbol of his station. It is these kinds of legacies that can lie under the surface of country house histories, connections which are not at first obvious but become physically embodied in the houses and furnishings.

A country house is a compound of elements that involves the owner and residents, the wealth that built and maintains it, and the features displayed within it, whether this is architectural and interior design, or art objects. Nationally the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw numerous connections between Caribbean plantations and British country houses across all of these dimensions. The historian Stephanie Barczewski identified 211 estates that were acquired by West Indian planters between 1700 and 1850.11 Significantly, planters returning from the Caribbean believed that a country estate would be a method to establish their place within the upper realms of society. For example, William Beckford (1709-1770) was born in Jamaica; his family had been established on the island as plantation owners and enslavers two generations before. Beckford was educated in England and Europe before returning to Jamaica in 1736 upon his father’s death the year before. The inheritance that Beckford and his brothers received was said to be valued at £300,000.12 Beckford added eight more properties to the nine estates that he either owned outright, co-owned, or mortgaged to an extensive seventeen plantations, all worked by Black enslaved labourers.13

Beckford had political ambition and established himself in the Jamaican House of Assembly before campaigning in British politics. From London he would be able to influence politics that directly affected the interests of enslavers and plantation owners who were resident in the Caribbean and those who remained in Britain. Such a manoeuvre saw Beckford permanently move back to England in 1744. With the money from his plantations, and the drive from political ambition, Beckford needed the symbol that would show his position amongst British society: a country estate. In 1745 Beckford purchased Fonthill estate in Wiltshire for £32,000. As an outsider who retained his Jamaican accent, Fonthill was a way for Beckford to fit in with the other social elite in Britain; it was a way that he could establish himself as a country gentleman ‘in a land where the gentry remained the social and political backbone of the state.’14 The estate was intricately connected to Beckford’s affairs The estate was intricately connected to Beckford’s affairs in Jamaica, as it had actually been necessary to take out a mortgage to pay for the property. Perry Gauci suggests that, during a trip back to Jamaica in 1749 he sold two plantation estates to pay off these mortgage debts. At the same time, he oversaw the purchase of newly arrived captured enslaved people aiming to improve the productivity of his remaining plantations.15

10Warwickshire Record Office CR1998/J/Box75 ‘Settlement to the marriage of Sir Robert Throckmorton and Lucy Heywood’.

11Stephanie Barczewski, Country Houses and the British Empire, 1700-1930, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), p.71.

12Amy Frost, ‘The Beckford Era’ in Caroline Dakers (ed.) Fonthill Recovered: A Cultural History, (London: UCL Press, 2018), p.60.

13Perry Gauci, William Beckford: First Prime Minister of the London Empire, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), p.148.

14Gauci, William Beckford, p.52.

15Gauci, William Beckford, p.58

23

The wealth from plantations in Jamaica went to improve Fonthill House which had a historical pedigree to aid Beckford’s climb in society. He changed the grounds of the estate, including moving a public road and adding an external archway.16 The internal work done to the house was said to have cost £5000 a year and employed people from all the neighbouring parishes.17 However, this building work led to a fire in February 1755, destroying much of the property, though servants managed to remove the furniture. The damage was extensive, estimated at £30,000. Yet alongside his fortune, Beckford’s reputation had been cemented, as Horace Walpole wrote in a letter in reference to Beckford and the fire ‘He says “Oh! I have an odd fifty thousand pounds in a drawer: I will build it up again”’.18 Walpole’s letter highlights how significant Beckford had become through his plantation wealth to the extent that rebuilding a country house worthy of his political and social status, would appear trivial. Significantly, an unnamed Black person lost their life in unknown circumstances before the fire took place.19 Who this person was is unknown but their presence in the house may suggest that they were brought from Jamaica to Fonthill to act as a servant in the house, another method for Beckford to indicate his imperial connections and status among the political and social elite. The mysterious circumstances of this Black person’s life and death highlight that whilst it is possible to see how plantations in Jamaica benefitted Beckford’s social status through a obtaining a country house, the individual Black people are lost within this shadow.

Although the £50,000 in a drawer was likely an exaggeration by Walpole, Beckford did spend money on building an entirely new house, Fonthill Splendens. In its Palladian style, Splendens served as Beckford’s country residence, as a symbol of his status within a society that ordered social position based upon taste and aesthetics. With money from plantations and enslaved labour, Beckford was able to buy his way into these reaches of society.

Beckford serves as an extreme figure to represent the processes of turning Black enslaved labour in the Caribbean to social success through acquiring a country seat. Warwickshire has its own story in the form of Samuel Greatheed who followed a similar path to Beckford. Greatheed was born in Saint Christopher, now St. Kitts, in 1710. His father had already been established on the island with a plantation, which Greatheed inherited after his father’s death, valued at £3000. Like Beckford, he was educated in England, where he attended the University of Cambridge and became MP for Coventry in 1747. As Beckford did, Greatheed similarly acquired a country estate, Guy’s Cliffe, first leasing the estate in 1747 before he bought it in 1750 (Figure 2.2). The estate was home to the legend of Guy, Earl of Warwick, where it was said that he returned from a military campaign and lived as a hermit in a cave that was on the estate. Guy’s Cliffe sits just outside Leamington, which, at the time of Greatheed’s purchase, was not developed into the popular spa town it would become. Now in his possession, Greatheed set about improving the house. He added a new wing in a neo-Palladian style, made from Warwick sandstone, adding an ionic porch and pediments. The interior of the entrance hall was decorated in a rococo plasterwork, whilst another room off the entrance hall had a gothic fireplace.20 With a country estate, and the money to renovate, Greatheed would have been able to fit within the upper reaches of society, able to entertain at a large scale, enabled by the proceeds from enslaved labour.

16Frost, ‘The Beckford Era’, p.61.

17Leeds Intelligencer and Yorkshire General Advertiser, 25 February 1755.

18Horace Walpole to Richard Bentley, 23 February 1755, in The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, W. S. Lewis and Warren Hunting Smith (eds.), (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937 and 1984), p.211. Quoted in Frost, ‘The Beckford Era’, p.63.

19Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 22 February 1755.

20Geoffrey Tyack, Warwickshire Country Houses, (West Sussex: Phillimore & Co Ltd, 1994), p.102.

24

It is through Greatheed’s son, Bertie that more is known about the plantations in St Kitts. After Samuel’s death in 1765, the plantation was managed on behalf of Bertie by his uncles, who received £200 a year as salary, until he reached twenty-one. Letters from a cousin to Bertie’s mother show concern in November 1773 of rain that may affect the last crop to be cut and in February 1774 for the dry weather and how this may affect the crop yield. Financial value is the common theme found in the archives that hold material on plantations worked by enslaved people.21 The letters from Bertie Greatheed’s cousin provide information on concern for crop yield and his own career opportunities but little else about the people who were enslaved to the land. Some of Bertie’s accounts hint at the conditions experienced by the enslaved people.35 There were 152 enslaved people registered to the plantation in 1781 and 146 in 1786. The accounts note medical care provided and a midwife, Kitty Payne, who tended to the delivery of eight women. Kitty herself may have been an enslaved woman, as this may have been one avenue that she could have earned money outside the system of slavery. However, this same document also notes payment for three neck collars and payment for the capture of runaway people. Bertie is said to have been an abolitionist, the conditions of enslavement may have been eased by doctors and payments to people like Kitty, yet it was enslaved labour that had paid for Guy’s Cliffe in Warwickshire where Bertie lived. As an absentee enslaver, the conditions were so distant from the house of Guy’s Cliffe. The Greatheed legacy in Warwickshire began with Samuel Greatheed’s purchase of Guy’s Cliffe and continued through this established social authority through Bertie. With the acclaim that a country residence provided, when the sugar market slumped Bertie was able to sell land for the development of Leamington Spa.22

The legacy of slavery further continues in Warwickshire through the Beckford-Fonthill line as well. William Beckford’s son, also named William, inherited the plantations and labour of enslaved people in 1770. With the wealth accrued he was able to travel Europe and build an immense art collection, all to be housed in the spectacle of Fonthill Abbey, which to complete, he demolished Fonthill Splendens. The dip in sugar prices, amongst other reasons, led Beckford to sell his estate and art collection in 1822 for £300,000.23 The buyer, John Farquhar, sold the collection at auction the following year. It is here that George Hammond Lucy, the recent inheritor of Charlecote Park, with an eager anticipation to furnish his home with beautiful art objects, purchased sixty-four items from the Fonthill sale. Charlecote Park near Stratford-on-Avon, originally a Tudor house with some eighteenth-century renovations, becomes the home for these objects and their associations with enslavement.

The Lucys of Charlecote have no direct connection to plantation slavery, but the family are representative of the wider effects of the slavery system which affected much of Britain. People like Beckford act as nodes which connect places like Charlecote Park to enslaved labour. These objects were only available to George Hammond Lucy because they were curated by William Beckford. Although these pieces have a history of their own, Beckford was only able to afford them because of his wealth derived from enslaved labour. The famous pietra dura table sits in the great hall of Charlecote Park, it is made up of a mosaic of hardstones including jasper and onyx, on an oak base which was made for Beckford; the

21Warwickshire Record Office CR1707/30.

22See Noel Deere, The History of Sugar, vol. 2. (London: Chapman and Hall Ltd., 1950) for sugar prices; Geary, F. Keith, ‘’An Eligible Spot for Building’: The Suburban Development of Greatheed Land in New Milverton, 1824 – c. 1900’, Warwickshire History, vol. XV, No. 5, (2013), pp. 218-219.

23Bodleian Library MS Beckford b.8 f.19-20.

25

Figure 2.3. The Great Hall, Charlecote Park, with the pietra dura table in the centre © National Trust Images/Andreas von Einsiedel

table was said to be from the Borghese Palace in Rome (Figure 2.3).24 At the auction, George Lucy bid against the Prince Regent for the table, paying 1800 guineas, nearly half of his total spend at the auction.25 The table is one of the most impressive pieces at Charlecote, the Prince Filippo Andrea Doria-Pamphili Landi, XI of Italy, visited Charlecote in 1838 and was said to have been ‘in raptures’ with it.26 From the early nineteenth century, the table and other objects from the sale, including porcelains and furniture, were part of the interior landscape of Charlecote Park, displayed throughout the house as a show of wealth and taste for a gentry family. Yet, their arrival at Charlecote was facilitated by Beckford’s wealth from enslaved labour.

To conclude, country houses acted as methods to indicate wealth and a way to support social acclaim. Wealth from enslaved labour was the avenue taken by the Greatheeds in Warwickshire with much success. It allowed Samuel Greatheed to settle in the county, establish a career and begin a legacy still present today. Similarly, Coughton Court highlights how connections can be made for financial gain to further bolster the acclaim of a country seat. Furthermore, the Beckford objects at Charlecote Park show the covert methods that connections to slavery can manifest. In an effort to create a worthy collection within a country house, George Hammond Lucy inserted Charlecote Park into a history of enslavement through objects with a generational legacy of enslavement. Little, if any, information about the lives of the enslaved Black people who worked the plantations belonging to the Heywoods, Beckfords and Greatheeds is known. The outcome of their efforts are instead shown in the form of grand buildings, collections, and histories of others. These houses and their contents may perhaps be considered Black Atlantic histories.

24William Beckford, A catalogue of the costly and interesting effects of Fonthill Abbey, (London, 1823).

25Mary Elizabeth Lucy, Biography of the Lucy Family at Charlecote Park in the County of Warwickshire. (London: privately printed by Emily Faithful & Co, 1862), p.127.

26Alice Fairfax-Lucy, Mistress of Charlecote: The Memoirs of Mary Elizabeth Lucy, (London: Orion, 2002).

26

Chapter 3

Plantation Tools and Bowie Knives: Rethinking Sheffield’s Local Connections to Atlantic Slavery in the Nineteenth Century

Tobias Gardner

In 1827, the Sheffield Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, led by the well-known social reformer Mary Anne Rawson, became the first organisation to advocate for ‘immediate, and total abolition’ of slavery within British plantation colonies.1 Although this was a ground-breaking moment, it was just one step on the long journey of antislavery activism within the city of Sheffield. During the campaign to end the British slave trade (c.1787-1807), freemen of the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire sent abolitionist petitions to parliament, and female activists in the Steel City organised boycotts of sugar produced by enslaved people in the West Indies. Relatedly, Sheffield was a regular haunt for touring antislavery celebrities from across the Atlantic world, such as William Wilberforce and William Lloyd Garrison and the Black abolitionists, Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass. Accordingly, for those interested in Britain’s historic relationship to Atlantic slavery, both in historiography and popular memory, Sheffield’s abolitionist politics has offered an encouraging counter-narrative. In contrast with port towns like Liverpool and Bristol or merchant centres such as London and Glasgow, Sheffield’s economy did not obviously benefit from the enslavement of Africans in the Americas. However, this primary focus on the Steel City’s antislavery movement has obfuscated the commercial connections between industrial Sheffield and plantation economies in the wider Atlantic world.2

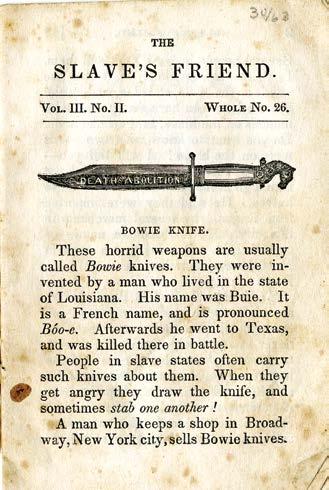

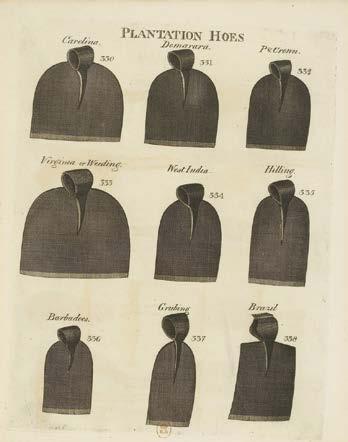

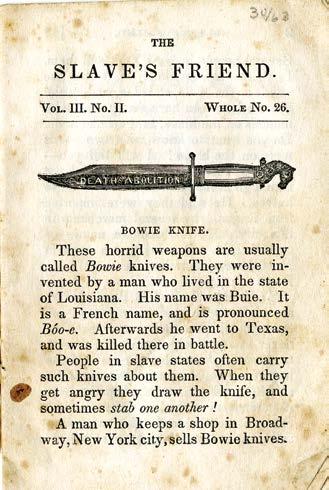

This chapter introduces two material case studies to unearth a more complicated picture of Sheffield’s relationship to Atlantic slavery. Firstly, it examines how Sheffield manufacturers were trailblazers in the production of plantation tools used by enslaved Africans across the Americas right up to Brazilian abolition and the end of Atlantic slavery in 1888. Various Sheffield firms specialised in manufacturing edge-tools such as hoes, scythes, adzes, and axes, that were crucial to the production of Atlantic commodities such as sugarcane, cotton, tobacco, and rice. Plantation tools were uninspiring and mass-produced, yet they became essential to the fabric of enslaved people’s lives symbolising their arduous labour, and even being used as weapons in resistance. Thus, analysing these tools not only reveals Sheffield’s economic connection to slavery, but provides some insight into the lives of enslaved people. Secondly, this chapter explores Sheffield’s monopoly on the production of Bowie knives for US markets, especially in the Southern States. Bowie knives were folkloric and often deluxe products favoured by US enslavers, and therefore Sheffield cutlers were known to inscribe them with mottos such as ‘Death to Abolition.’ The production of these knives created social controversy amongst abolitionists across the Atlantic and studying them helps to reveal the extent to which Sheffield’s cutlery firms were commercially tied to the US South in the nineteenth century. Indeed, as will be seen, these economic connections became essential during the American Civil War, and motivated a strong pro-Confederate movement in Sheffield, which undermined the city’s antislavery history.

1Sheffield Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Annual Report, (Sheffield, 1827), p. 6.

2For more in-depth information on this subject, consult: Michael D. Bennett and R.J. Knight, ‘Report on Sheffield, Slavery and Its Legacies’, (Sheffield, 2021): pp. 1-43. https://sheffieldandslavery.wordpress.com/report/

27

Of course, Sheffield’s economic development was not defined by Atlantic slavery and a more global story can be told. Sheffield manufacturing relied upon iron ore imports from Scandinavia, and many of the city’s exports were not associated with the Atlantic, instead going to Asia, Europe, and elsewhere in Britain. As such, there is no suggestion made here that Sheffield’s industrial connections place it into a similar category to the cities with more dependence on Atlantic slavery. The evidence does not justify making such a claim. Rather, the aim of this chapter is to demonstrate how an original focus on specific industries can shed new light on seemingly well-established accounts in Britain’s social and economic history. These material case studies can begin to expose how Britain’s manufacturing heartlands were also tied to slavery, and how this was debated in socio-political life. Narrowing in upon Sheffield’s local history, therefore, serves a threefold function. Firstly, it disrupts prevailing celebratory assumptions that Britain’s industrial inland cities were somehow typified by unwavering abolitionist sentiment, and isolated from the Atlantic slavery system. Secondly, it represents a call to move beyond coastal cities and merchant centres as the sole geographic regions through which to understand Atlantic and global economic history. Thirdly, then, demonstrating how Britain’s industrial centres maintained commercial connections to slavery economies beyond British abolition in 1838, complicates the view that British imperialism from the mid-nineteenth century was legitimised through antislavery ideals.3

Plantation Tools

As summer drew to a close in late August 1790, Britain’s leading formerly enslaved activist, Olaudah Equiano, stopped off within the hills of Hallamshire on his nationwide antislavery lecturing tour. Whilst there, Equiano addressed over seven hundred South Yorkshire abolitionist sympathisers, and promoted his new book, an autobiography that provided a powerful personal testimony on the horrors of the middle-passage and enslavement within the Americas.4 As noted, this much about Sheffield’s abolitionist culture is well known, however it is interesting to ponder how some Sheffielders, especially in the manufacturing industry, may have reacted when they read certain passages of Equiano’s work. Indeed, Equiano recounted observing the inhumane conditions on plantations, such as on the island of Montserrat in the Caribbean, where ‘wretched field slaves [toiled] all day for an unfeeling owner who [gave] them but little victuals.’5 The plantation tools used by these enslaved peoples during this arduous forced labour might easily have been imported from manufacturers within the Steel city.

The development of Sheffield’s tool making industry from the seventeenth century to the twentieth century has been a source of pride amongst local historians and heritage enthusiasts for many decades.6 There is no denying the expertise and skill of Sheffield manufacturers behind the tools trade, and the efforts of merchants to export these articles across the world. Yet as the global impact of these industrial developments are studied further, certain uncomfortable legacies are steadily being excavated. Along with cities like Birmingham, Sheffield was a key site for the manufacture and export of tools used by enslaved people across plantations in the Americas, from the 1600s right up to the eventual abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888. Throughout the nineteenth century Sheffield tools were also important to the development of new oppressive ‘free-labour’ regimes within Britain’s expanding imperial territories, especially in Oceania and Asia. However, the experience of trade with slavery states around the Atlantic Ocean was crucial in shaping Sheffield’s global manufacturing culture. As James McHenry, one of America’s slaveowning founding fathers, argued in a Virginia newspaper in 1805, ‘Sheffield wares [including] a variety of edge tools, hardware, and ironmongery’ were key British imports to America, particularly the plantation economy, and added to the prosperity of both nations.7

3See: Richard Huzzey, Freedom Burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain, (Ithaca, 2012).

4The Sheffield Register, 20th August 1790, p. 2.

5Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Fourth Edition, (Dublin, 1791), p. 140.

28

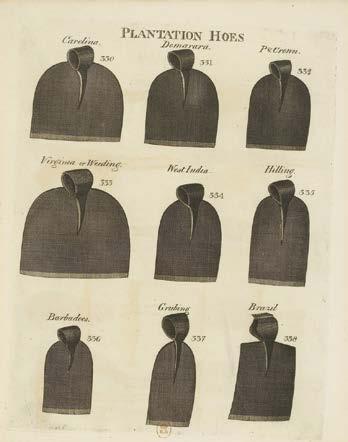

Figure 3.1. Joseph Smith, Explanation or Key, to the Various Manufactories of Sheffield, with Engravings of Each Article (1816).

Courtesy of Sheffield Local Studies Library

The most prominent of these tools, and the one that has received the most attention from historians, was the plantation hoe (Figure 3.1). The hoe in many ways became a synecdoche for Atlantic slavery. It was an article almost uniquely designed for the cultivation of those crops –sugarcane, cotton, rice, and tobacco – that fuelled European colonisation of the Americas.8 As Figure 3.1 depicts, Sheffield plantation hoes were adapted and innovated to be exported across the vast colonial markets in the Americas, to be used on plantations in locations as far flung as Brazil, Virginia, and the West Indies. Yet despite this regional variation and market adaptability, the evidence suggests that hoes were not particularly high-quality and instead designed for mass-production. In a telling revelation of 1831, the Sheffield poet, John Holland, explained that plantation hoes were cheaply made as they were ‘used by persons [enslaved people] whose time and labour are accounted of no great value, and whose comfort is rated still lower.’9 As historians have affirmed, hoes were central to the ‘backbreaking grind of labour’ on plantations, and were designed not as implements of expertise, but instead to maximise profits and ultimately the exploitation of the enslaved labour force.10 Within British abolitionist literature, the hoe was subject to severe criticism as a brutal, premodern form of agricultural technology, and often figured as a metaphor for enslavement itself. For Josiah Conder, the ‘primitive hoe’ was inefficient and formidable and thus was a ‘badge of slavery.’11 Also, given that many enslaved field workers were female, some writers focused on the gendered nature of the hoe, as it challenged nineteenth-century British ideals of feminine sensibility and domesticity. Whilst residing on a Georgia plantation, the female actor and abolitionist, Fanny Kemble, lamented how enslaved women were separated from their children and duties as ‘housewives’, and instead ‘condemned to field labour’ which reduced them to ‘human hoeing machines.’12

6Research into Sheffield tool making would be impossible without the life’s work of Ken Hawley, and the volunteers at the Hawley Tool Collection in Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield. See also the industrious work of Geoffrey Tweedale in Directory of Sheffield Tool Manufacturers 1740-2018, (Sheffield, 2020).

7The Enquirer, (Richmond, Virginia), 6th December 1805, p. 4. 8Chris Evans, ‘The Plantation Hoe: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Commodity, 1650–1850.’ The William and Mary Quarterly 69.1 (2012): pp. 71–100.

9John Holland, The Cabinet Cyclopaedia. Conducted by the Rev. Dionysius Lardner. A Treatise of the Progressive Improvement and Present State of the Manufactures in Metal. Vol. I. Iron and Steel, (London, 1831), p. 143.

10Justin Roberts, ‘The Whip and the Hoe: Violence, Work and Productivity on Anglo-American Plantations.’ Journal of Global Slavery 6.1 (2021), p. 109. 11Josiah Conder, Wages or the Whip: An Essay on the Comparative Cost and Productiveness of Free and Slave Labour, (London, 1833), pp. 18-57.

12Fanny Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839, (New York, 1863), p. 121.

29