Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

1

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Explore the Wende Museum with Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. This digital/mobile guide takes you behind the scenes with exclusive multimedia perspectives from the artists in Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Free to download and free to use, the app was created by Bloomberg Philanthropies to help make the art and offerings of cultural organizations more accessible— not just to those visiting in person, but to people around the world.

Download the app from BloombergConnects.org or by scanning the below QR code and then search for or scroll to the Wende Museum. After you have the app, you can scan the QR codes in this catalog to listen to the audio tour, featuring in-depth interviews and conversations with the artists in this exhibition.

November 11, 2023–September 15, 2024

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

WENDE MUSEUM

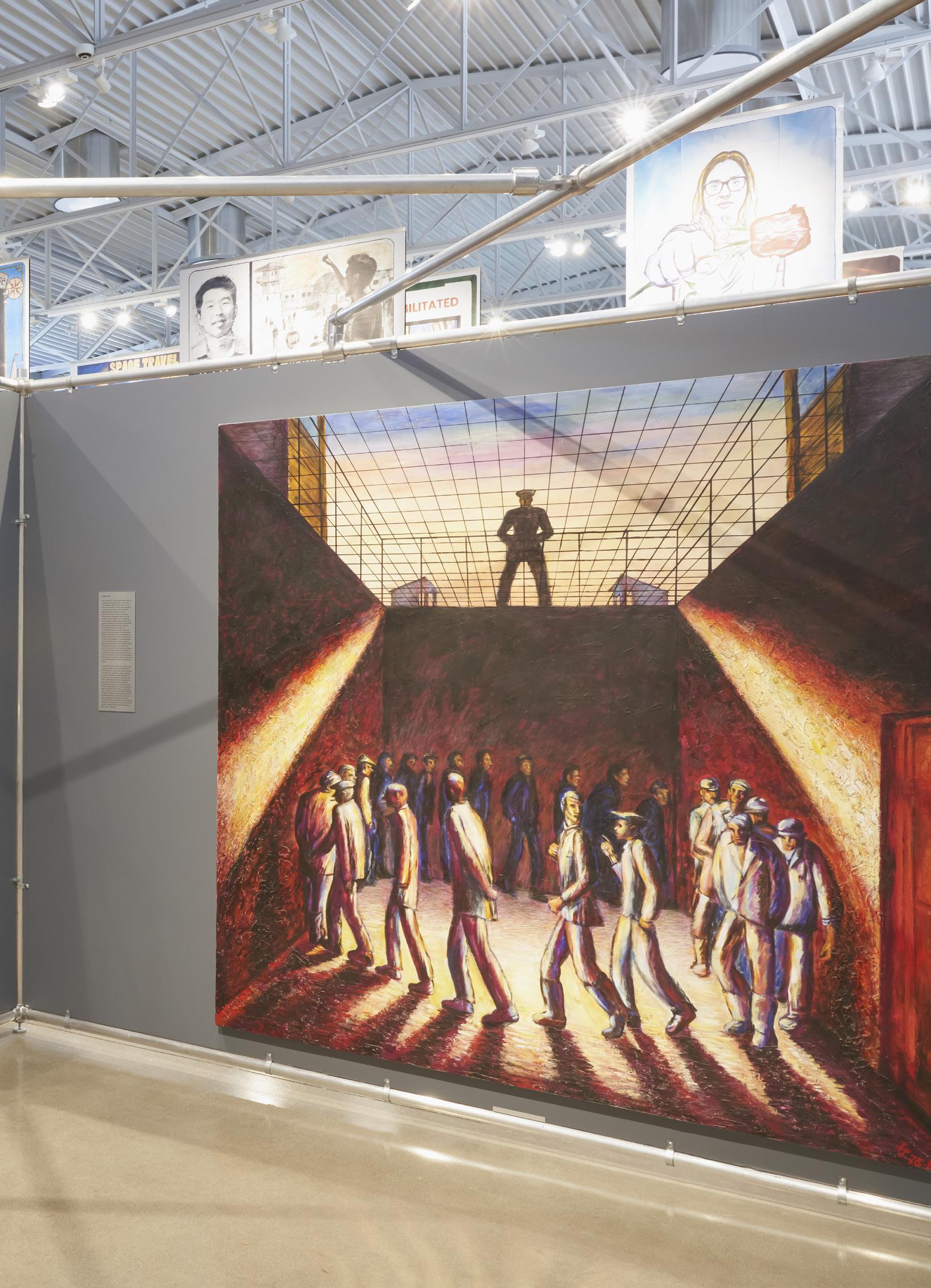

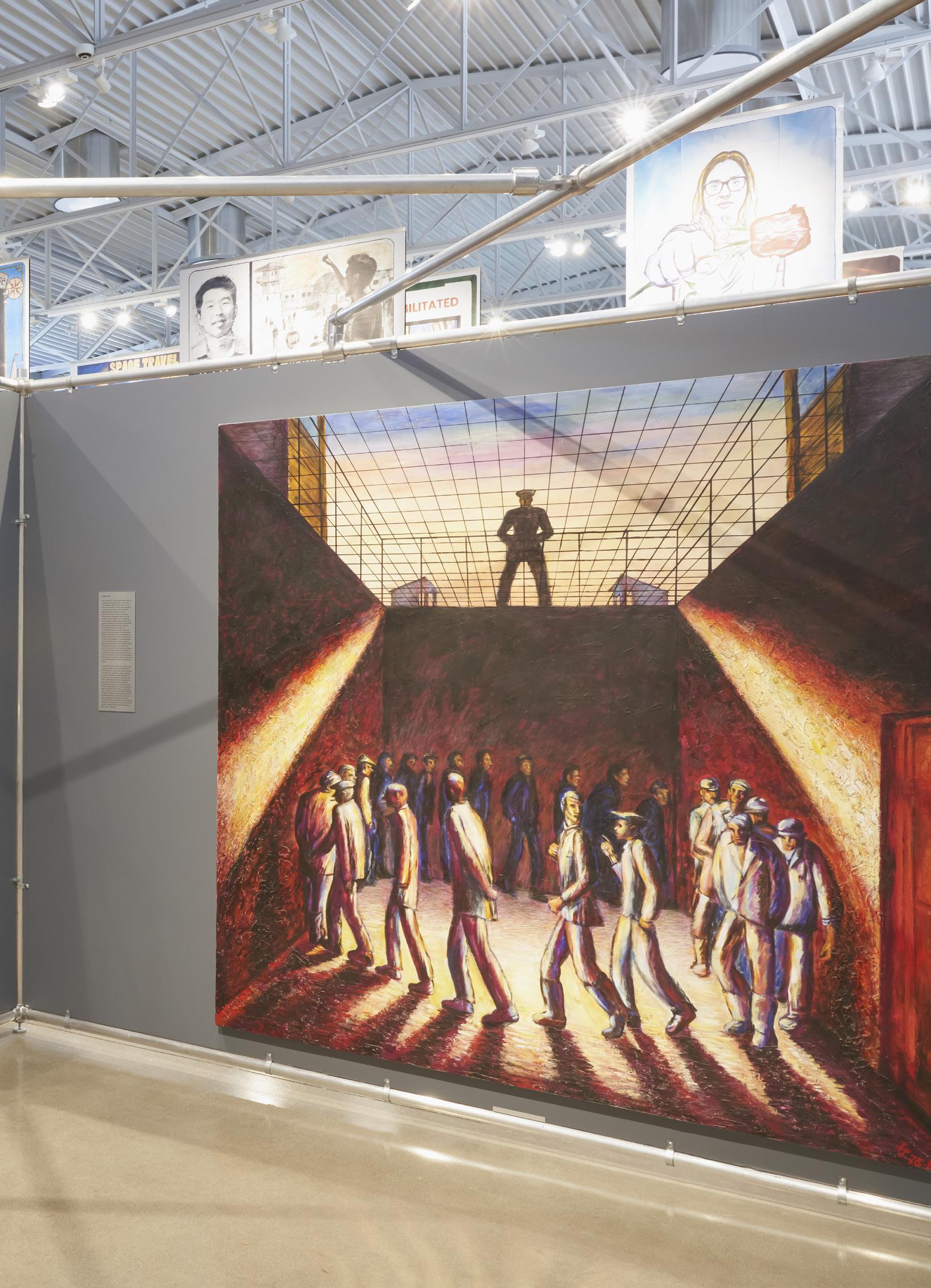

previous pages: Installation view of Leonid Lamm and Shepard Sherbell (Courtesy of Olga Lamm and Collection Wende Museum)

6 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

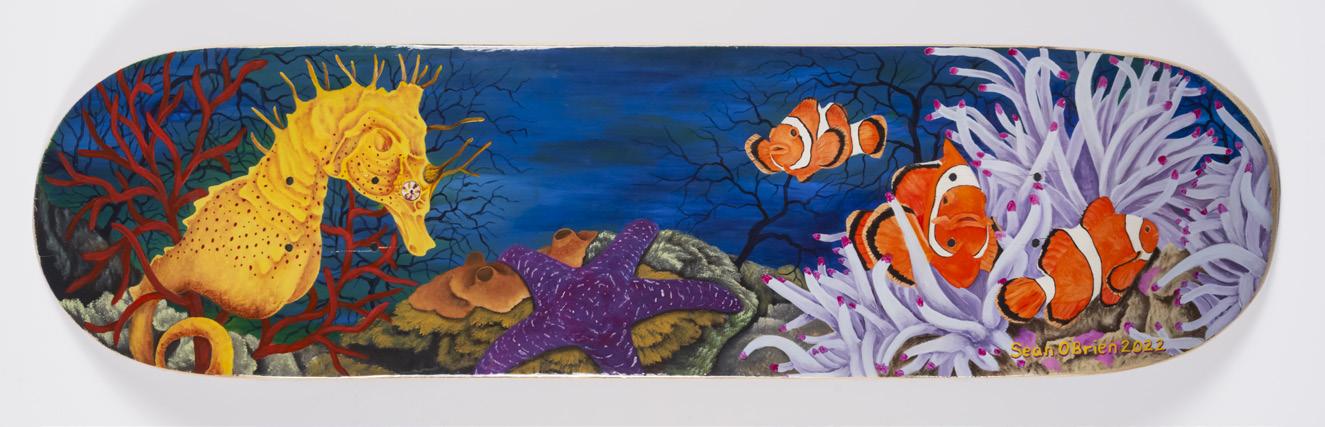

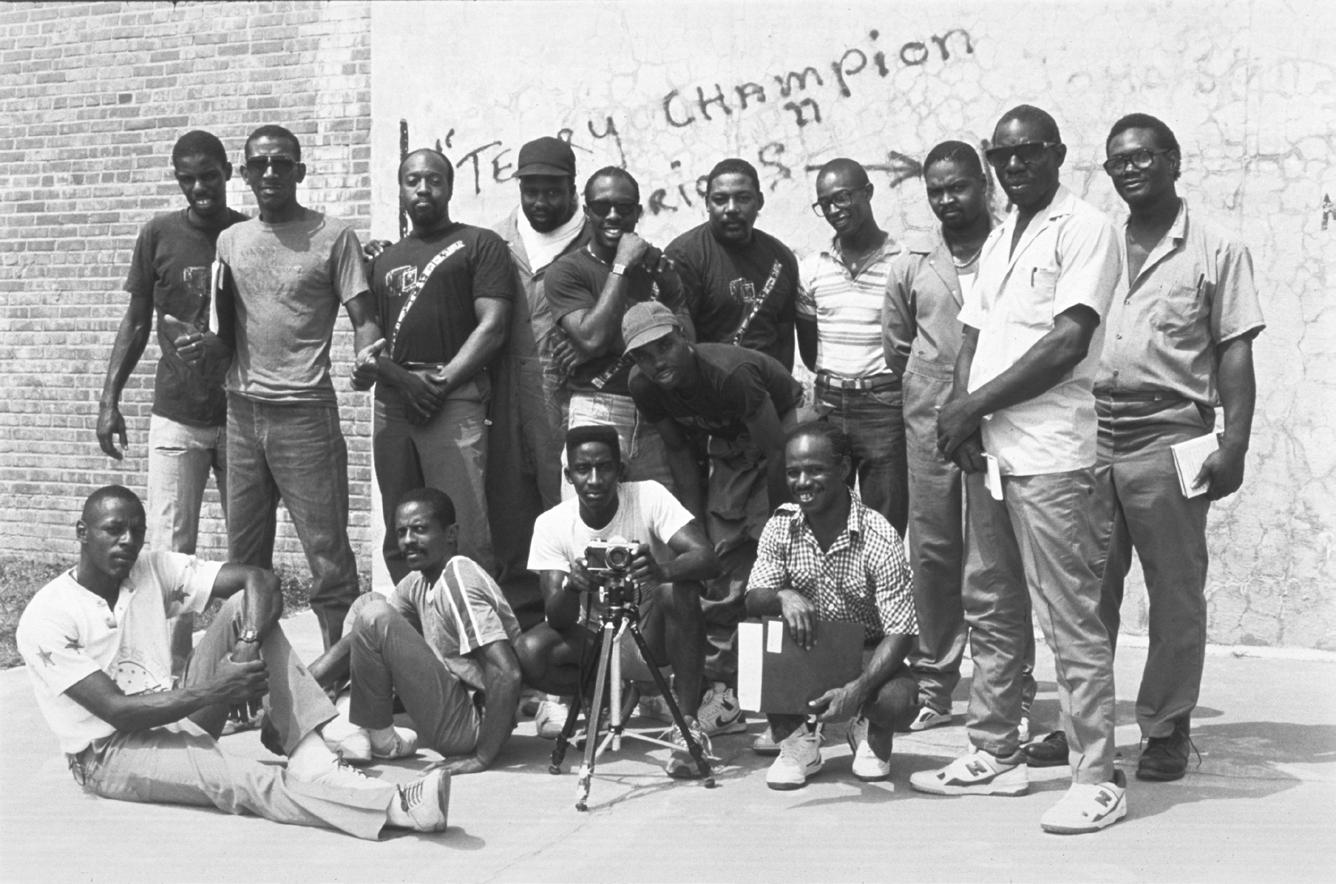

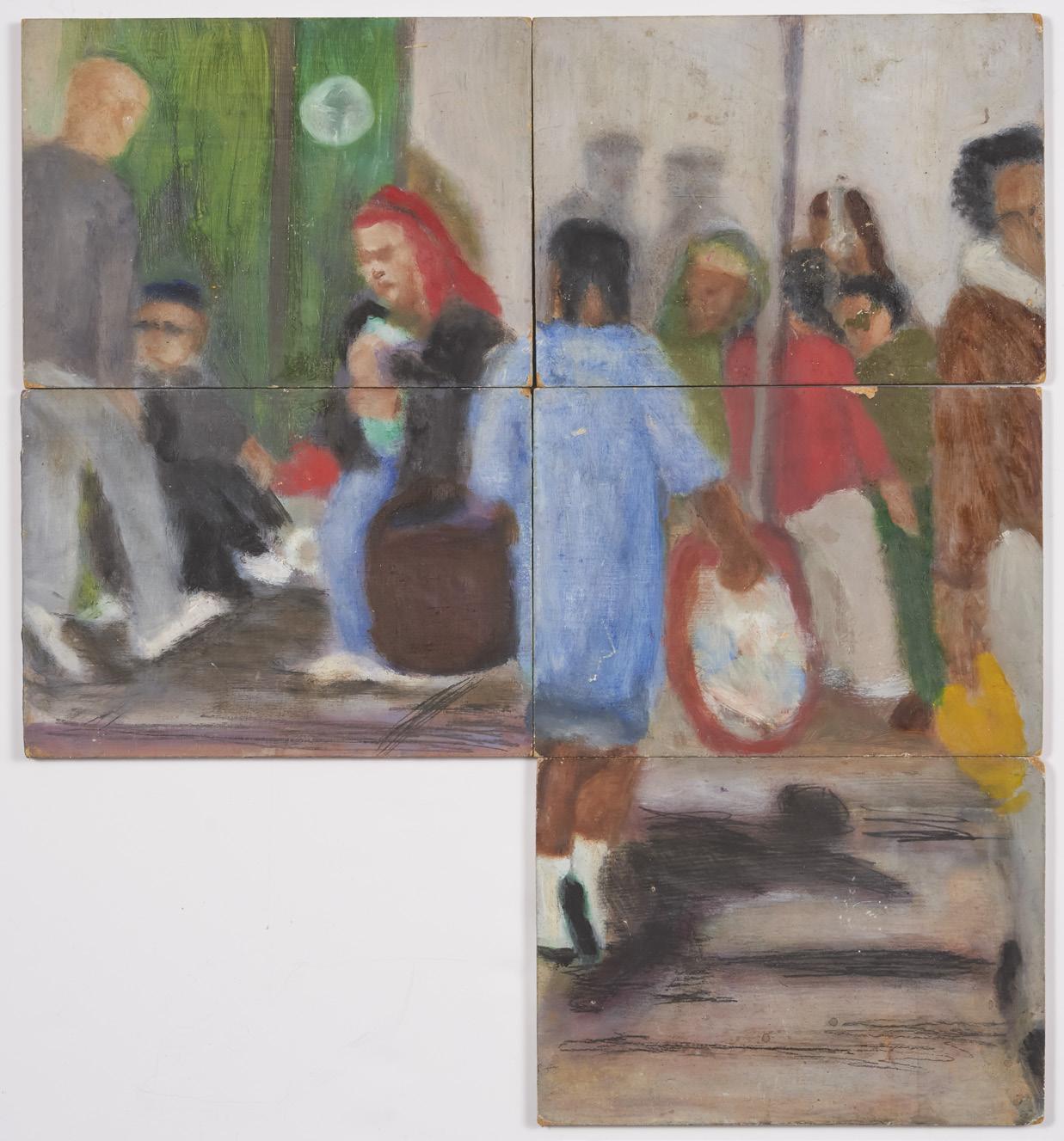

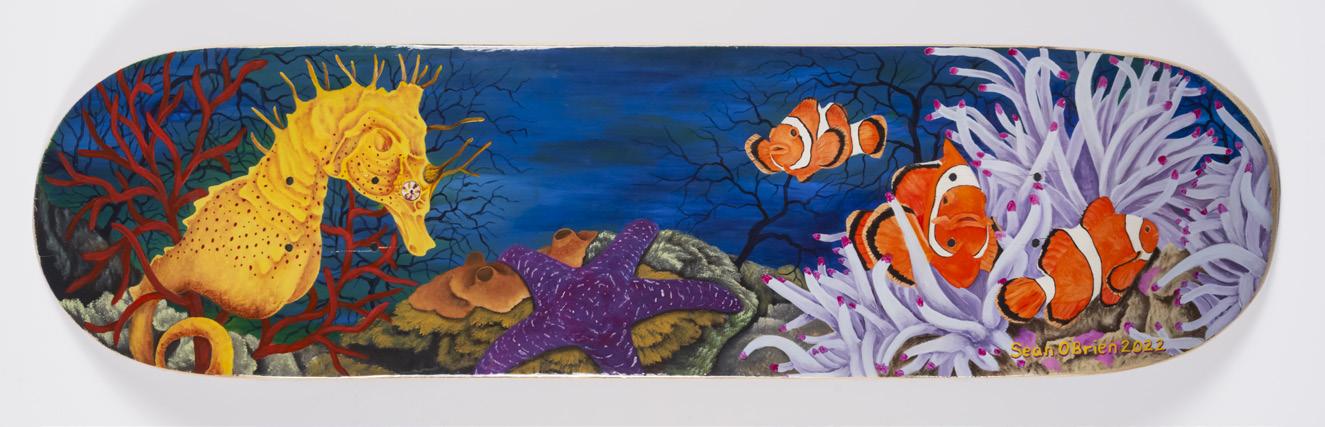

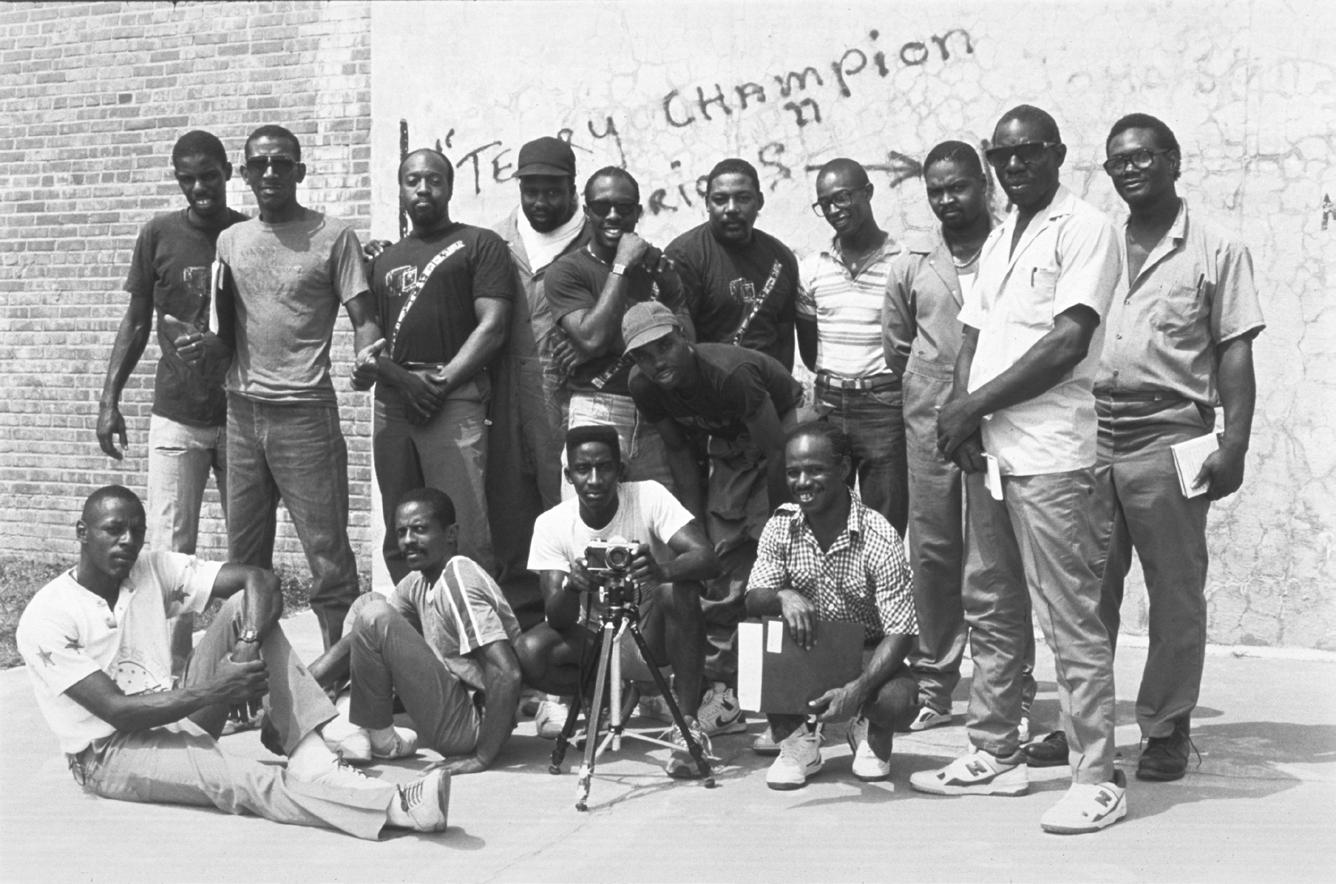

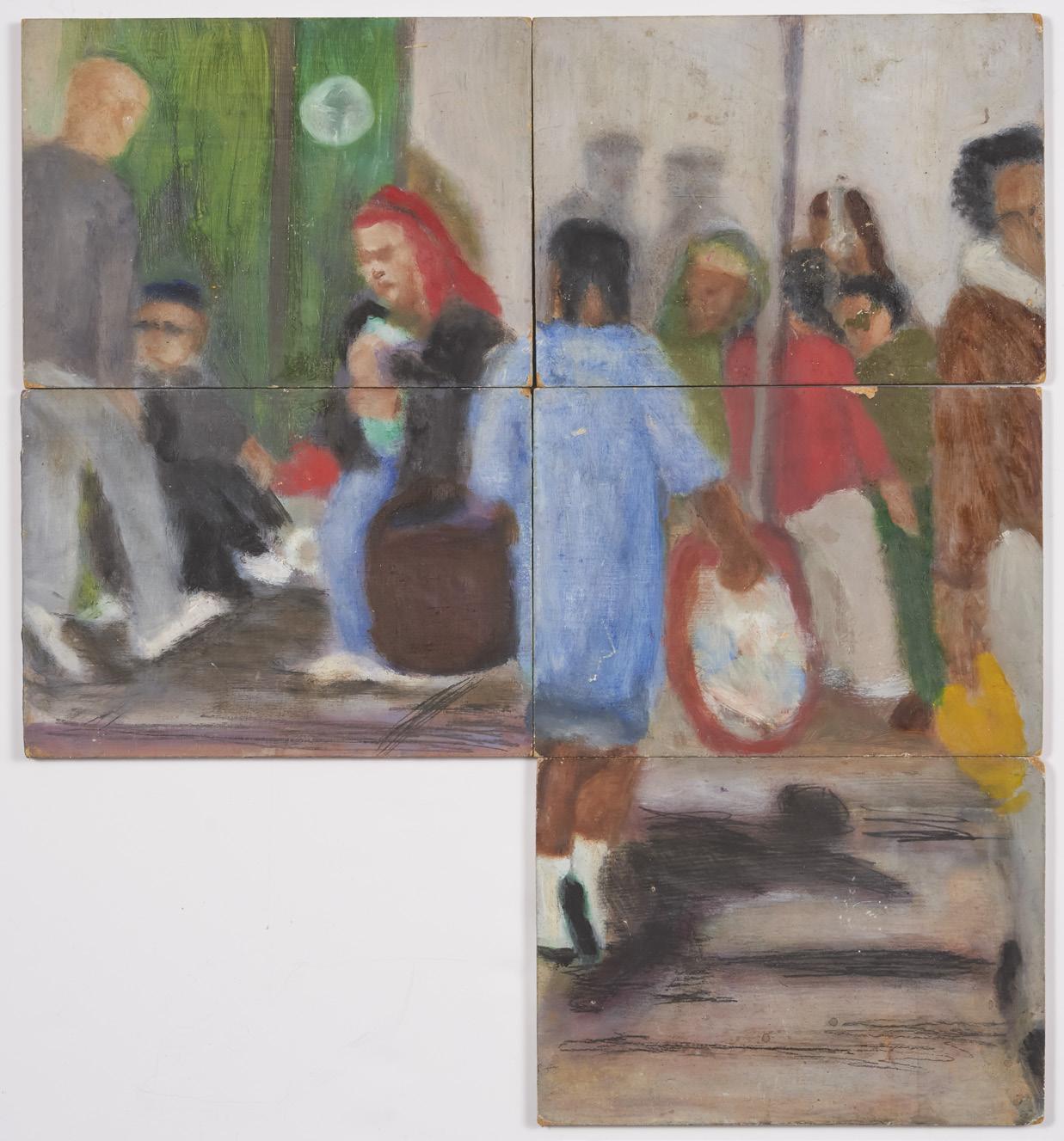

above: Installation view of Fresno Skateboard Salvage, Lorton Photography Workshop, Kitiona Paepule, and Sandow Birk (Courtesy of Rodney Rodriguez, Karen Ruckman, Kitiona Paepule, and Bill Nichols)

Introduction

While imprisoned in the Soviet Union from 1957 to 1964, sculptor Léonid Nedov clandestinely rendered scenes of prison life onto broken pieces of enamel dishware in haunting detail, until his release thanks to mediation by the famous dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Nedov’s powerful creative expression in the face of terror formed the inspiration for the exhibition Visions of Transcendence

Visions of Transcendence presents artwork created by people who have lost their right of privacy and security by being incarcerated or unhoused. The exhibition pairs art from the Soviet Bloc countries during the Cold War with the contemporary West, reflecting on the parallels and differences between two competing political systems. Irrespective of ideological regimes, the incarcerated and unhoused artists featured in Visions of Transcendence have created and continue to create their own visionary spaces with imaginative artwork, attesting to the healing power of art and creativity.

For artists in countries without a democratic system, such as the communist states during the Cold War, being accused of political or artistic non-conformism was often sufficient to be put away in a prison camp or mental institution. The exhibition presents works by artists who, like Nedov, endured imprisonment by finding escape through a wide variety of styles and creative means. We reflect on the

suppressive Soviet system alongside American society with its exceptionally high rate of incarceration and homelessness, showcasing imprisoned and unhoused artists who express their humanity and their often transforming stories through their art.

The Wende Museum expresses its deep gratitude to the many people and organizations who helped us realize this exhibition. They include all the featured artists as well as the Archive of Modern Conflict, Immigration Detention Archive (Border Criminologies, University of Oxford), Fresno Skateboard Salvage, Future IDs Project, Huma House, Library Street Collective, Los Angeles Poverty Department, the Museum of Chinese in America, The People Concern’s Studio 526, Prison Arts Collective, and Nochlezhka. Special thanks to Edgar Aguilar, Mary Bosworth, Henriëtte Brouwers, Annie Buckley, Alice Corona, Misty Dawn-MacMillan, Nicole Fleetwood, David Franklin, Jane Friedman, Steven Fullwood, Thao Ha, Phung Huynh, Meetra Johansen, Olga Lamm, Daniel Lee, Innesa Levkova-Lamm, John Malpede, Rodney Rodriguez, Ananya Roy, Bidhan Chandra Roy, Karen Ruckman, Leah Rutt, Gregory Sale, Aleksander Smukler, Xenia Solodova, Thomas Szlukovenyi, Nancy NG Tam, Laurence Thrush, Tonya Turner Carroll, and Khadija von Zinnenburg-Carroll.

7

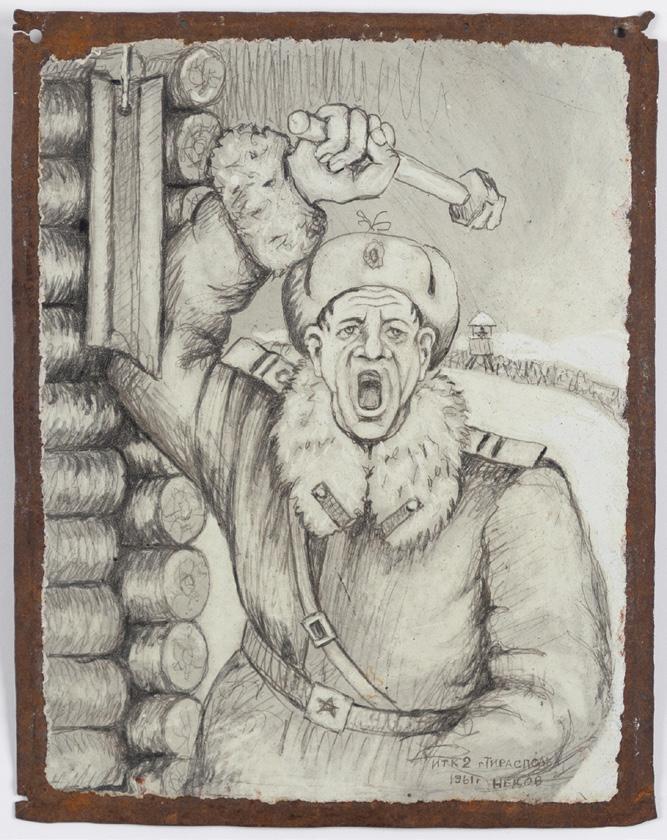

Léonid Nedov

Léonid Nedov was the son of a metal worker in the Moldovan city of Tiraspol. He wanted to study art but instead was recruited into the Soviet army in 1942 during World War II. After he was discharged in 1945, he tried to make ends meet by forging 50-ruble notes, which he used to buy food and study art. He was caught in 1957 and sentenced to death by firing squad, which was commuted to twenty-five years in prison. He spent three years in the infamous Kolyma gulag in Arkhangelsk but was transferred to the prison in his hometown of Tiraspol. The prison commander recognized Nedov’s artistic talent and granted him full use of the prison studio, where he was assigned with creating communist posters and statues, as well as door knobs in imitation of those in the palace of Versailles. Clandestinely, he also made statuettes, drawings, and enamels based on his experiences in Kolyma and in Tiraspol prison. He reportedly used soldering irons to

make the enamels on metal acquired from pails and washbasins. He hid some of his works in the hollow head of a large Lenin statue he was forced to make.

Nedov had access to the 1962 novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, which was published in the magazine Novy Mir (New World). He dedicated one of his small sculptures to Denisovich and was able to smuggle it out of prison with the help of his visiting mother, together with a letter to Solzhenitsyn. Solzhenitsyn received the sculpture and the letter and wrote back, ‘Your sculpture is made from the heart and reaches my heart.’ Through the interference of Solzhenitsyn, his lawyer, and two of his influential writer friends, Nedov was released from prison in 1964. They became friends, and Solzhenitsyn wrote about Nedov in the third volume of his The Gulag Archipelago

Hear more about the history of Soviet Gulags and how Leonid Nedov’s artistic talent helped set him free. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 678

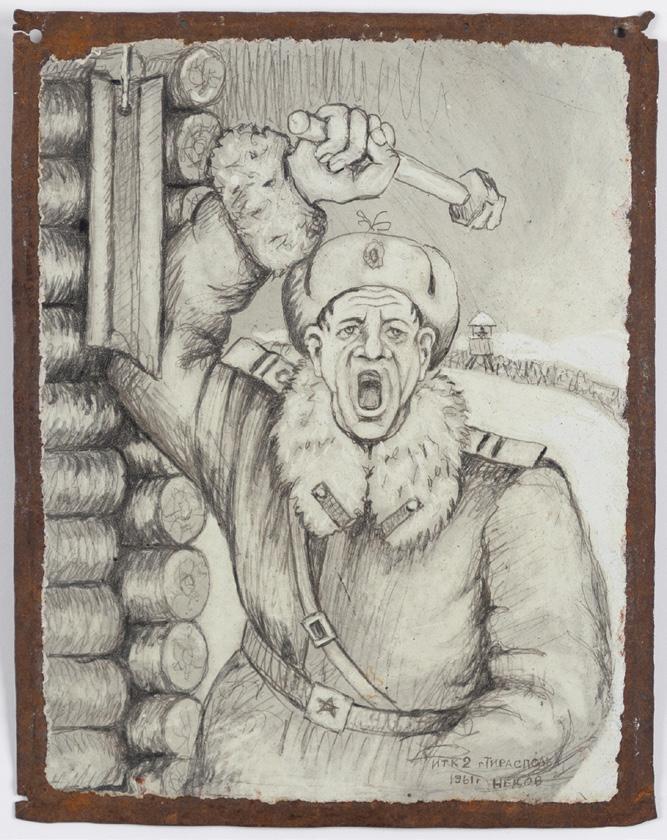

opposite, clockwise from top

Léonid Nedov, Prisoners, 1963, mixed media and enamel on metal

Léonid Nedov, Officer Chizhik, ITK-2, Tiraspol, 1963, mixed media and enamel on metal Officer Chiznik is mentioned by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago

Léonid Nedov, ITK-2, Tiraspol, 1961, mixed media and enamel on metal All courtesy of the Archive of Modern Conflict

8 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

9

Léonid Nedov,

Léonid Nedov, Inmates Breakfast, ITK-2 , 1960, mixed media and enamel on metal

All courtesy of the Archive of Modern Conflict

10

of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Visions

clockwise from top left

Léonid Nedov, Prisoner in Shower, 1963, mixed media and enamel on metal

Léonid Nedov, Stall, ITK-2, Tiraspol, 1962, mixed media and enamel on metal

Portrait of Solzhenitsyn in the Gulag, 1964, mixed media and enamel on metal

11

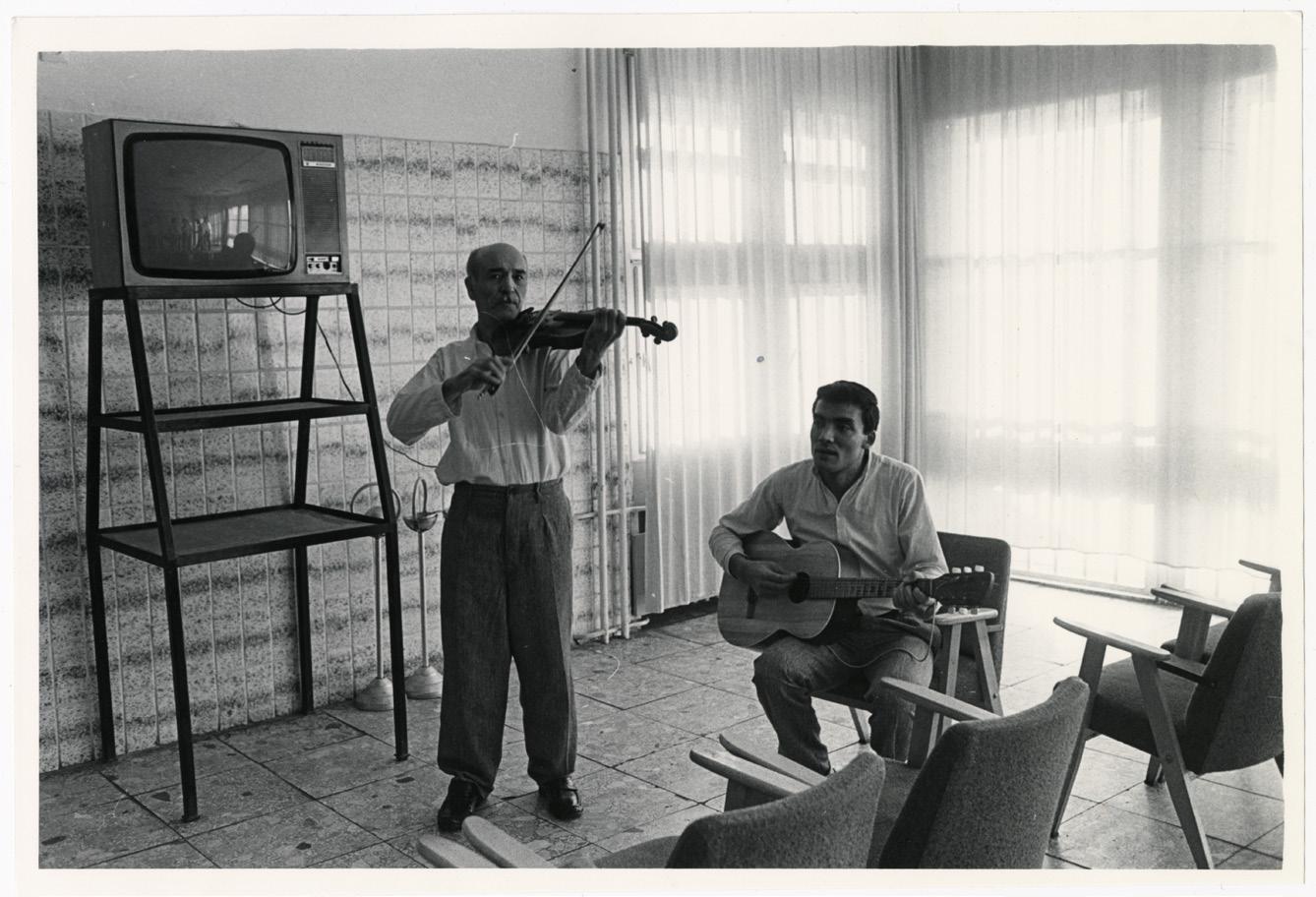

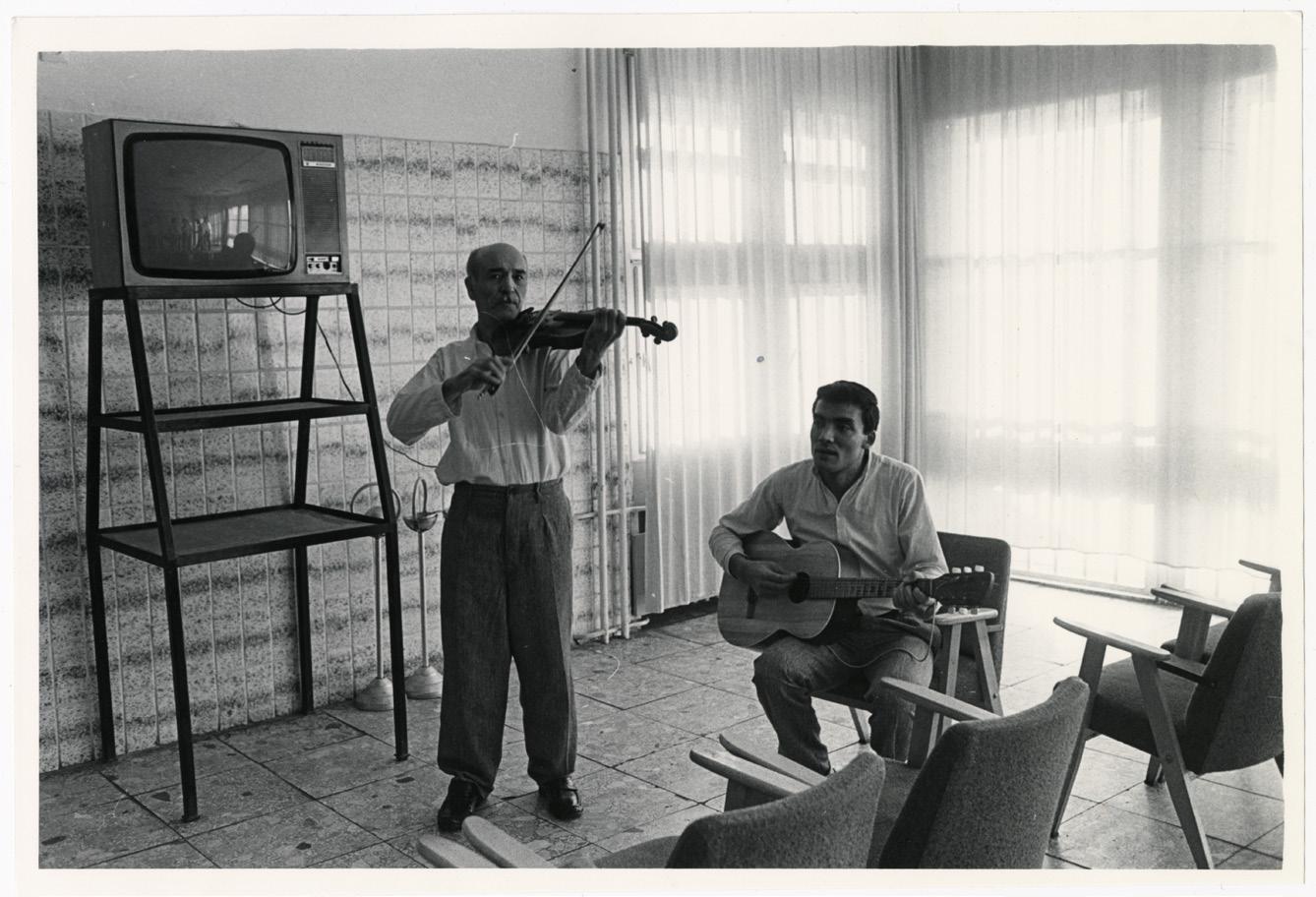

Léonid Nedov, The Violinist, 1963, mixed media and enamel on metal Courtesy of the Archive of Modern Conflict

Leonid Lamm

“On November 30, 1973, my parents filed documents to emigrate from the Soviet Union. It was a time of mass emigration of Jews from the country. On the afternoon of December 18, 1973, police approached Leonid Lamm on the corner of Gorky Street and Mayakovsky Square in Moscow. A scenario experienced by millions of Soviet citizens ensued. Without warning, the policemen began to beat him mercilessly as they dragged him into a police office. There the attack continued unabated until the artist was thrown against a wall, destroying a picture of Felix Dzerzhinsky, first chairman of Cheka, which later became the KGB. Lamm, the troublesome nonconformist artist who had earlier come to the attention of the police because of his public protests against the Soviet state, was arrested for destroying the picture and driven off to Moscow’s Butyrka prison, accused of ‘street hooliganism,’ an all-purpose charge used to incarcerate people who dared to speak out against the Communist Party and its workers’ paradise. His arrest came exactly three weeks after he had applied for an exit visa from the Soviet Union. As soon as my mother, Innesa Levkova-Lamm, was notified of my father’s arrest, she contacted a lawyer who

was my father’s childhood friend. When the attorney arrived at Butyrka prison, he was informed that he could not visit Leonid Lamm because he had been sent to the prison hospital.

From Butyrka prison, Lamm was sent to a labor camp near Rostov-on-Don at the end of February 1976. In July of that year, my mother wrote a letter to the head of the labor camp, requesting a visit with my father as she was concerned about his well being. Before the month was over she was granted a visit. When they met, my father slipped her all of the drawings he had done in prison, and she took them back home to Moscow, at great risk to both of them. All the works that were created during his imprisonment allowed my father to maintain his sanity during such trying times. This is a story of a man who found freedom for himself through art. He got to know the guards and prisoners, he heard their stories and made their portraits. As a result of exhibitions and publications around the world, these works became publicly known, a powerful expression of the totalitarian structures of his time. All together, Leonid Lamm was incarcerated for almost three years.” —Olga Lamm

12 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

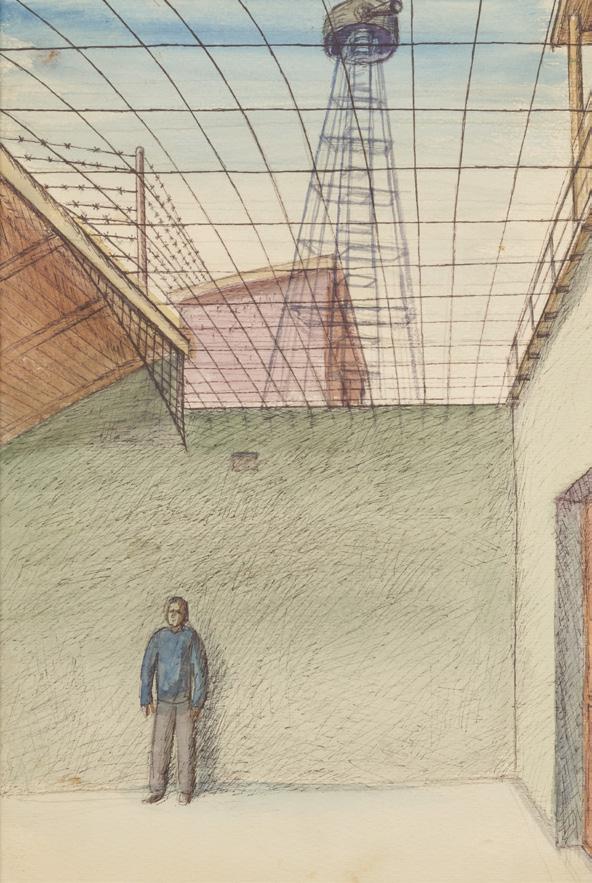

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

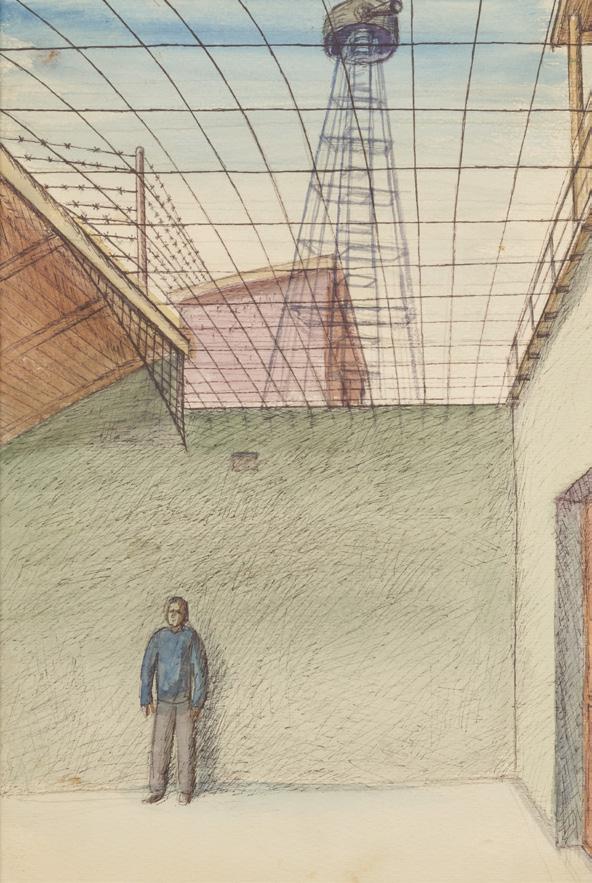

“In Butyrka prison, Leonid Lamm was allowed to go to the exercise yard once a day, where he would look at the Moscow sky, and breathe Moscow air where he spent over forty years of his life. Later, he would say, ‘Having to look at the sky through prison bars felt like a

catastrophe.’ One day he made a watercolor of this exercise yard. In 2016, this watercolor was recreated into this large oil painting. When I asked my father why he chose to do this, he said that he felt that the theme presently remains topical.”

—Olga Lamm

more

13

Leonid Lamm, Exercise Yard, Butyrka (Homage to Doré and Van Gogh), 1976-2016, oil on canvas

Hear

about Leonid Lamm’s monumental painting of the Butyrka prison camp’s exercise yard and why he decided to continue painting scenes from his incarceration even years after his release. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 602

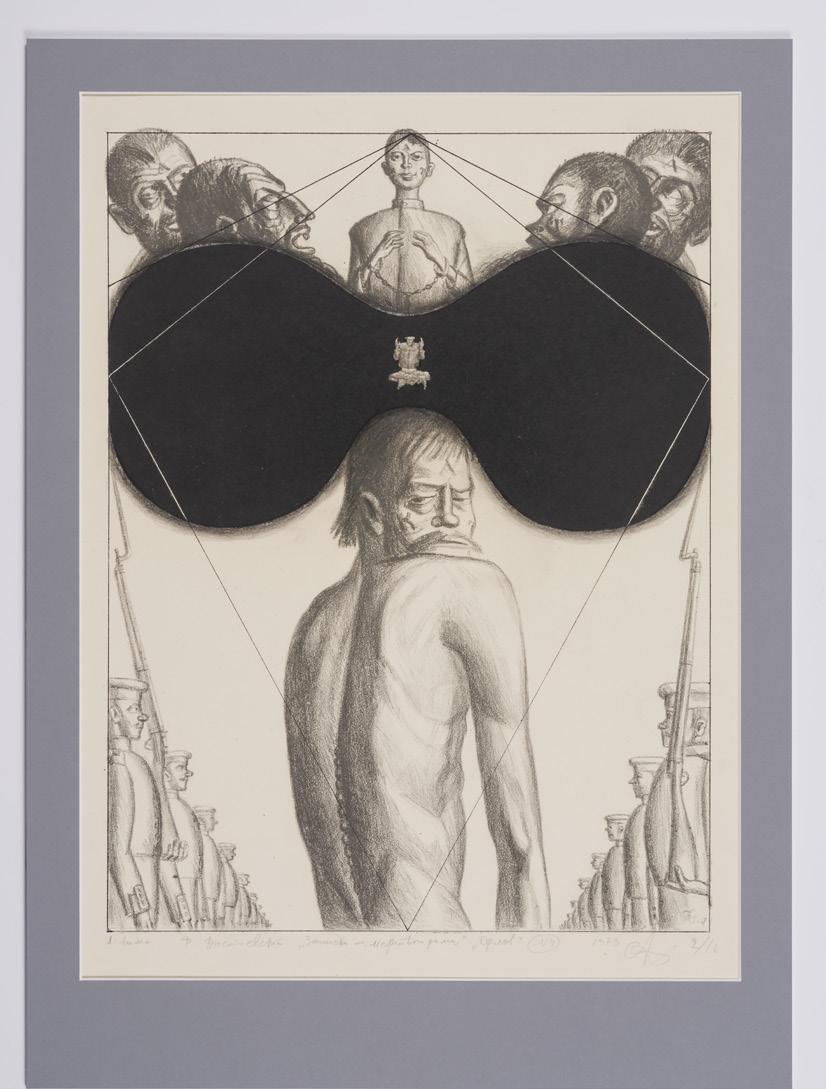

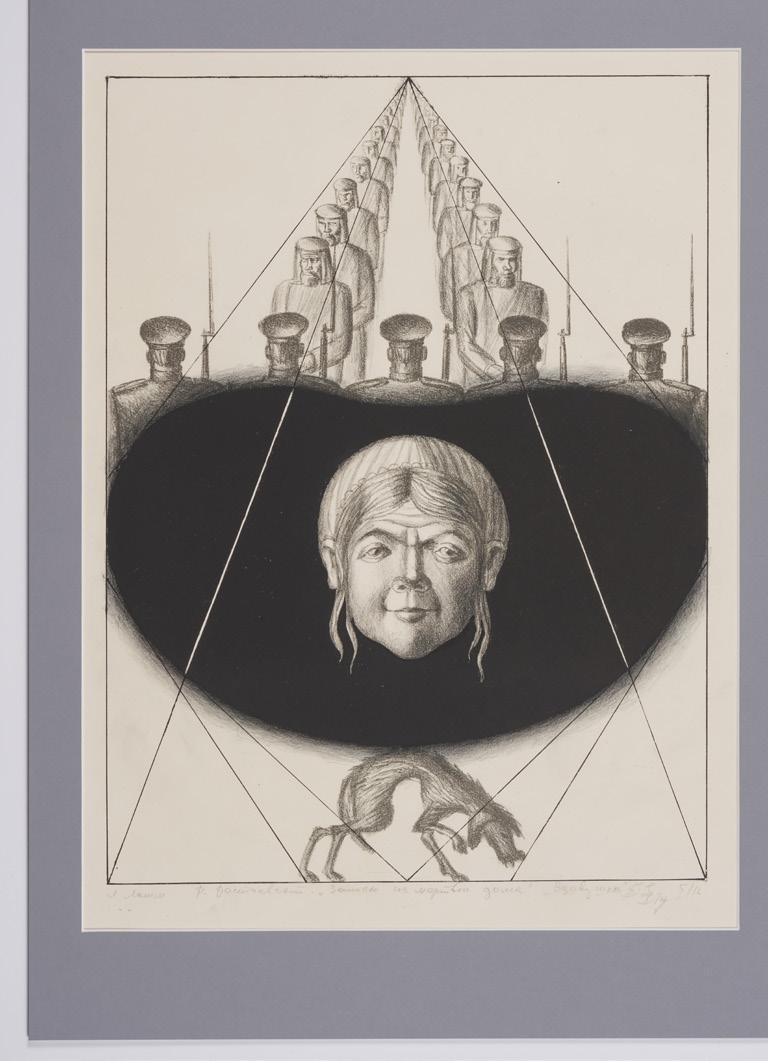

Leonid Lamm, Illustrations of Notes from House of the Dead

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

“Innesa Levkova-Lamm began writing letters to all publishing houses that worked with my father, who had by then illustrated over 400 books on various subjects, to request letters to be written on behalf of Lamm’s release. Over a dozen publishing houses sent letters to the prosecutor’s office asking for his release due to his valuable effect on Soviet culture and its expansion and evolution. Within a month, my mother was called to the prosecutor’s office where she was told that it makes no sense for them to receive such letters because they consider Leonid Lamm to be a dangerous criminal. When she asked what he was accused of, she got a single reply: ‘You know!’ Innesa Levkova-Lamm was told that if she approaches

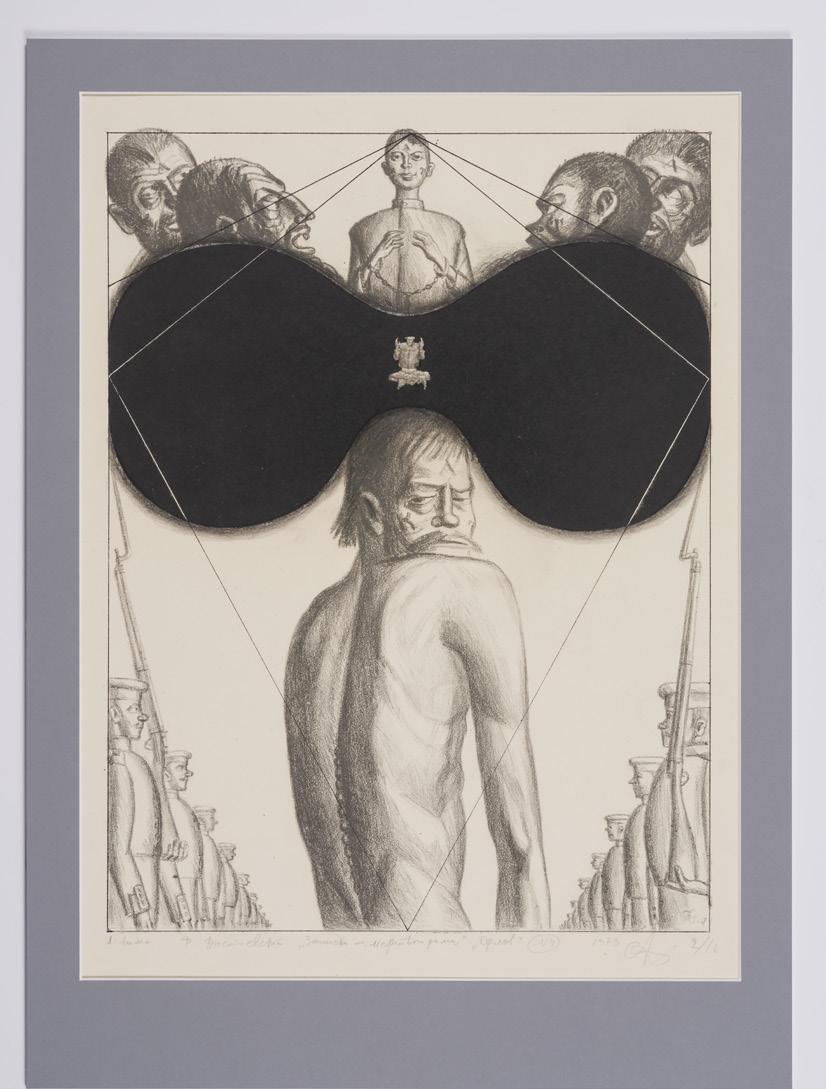

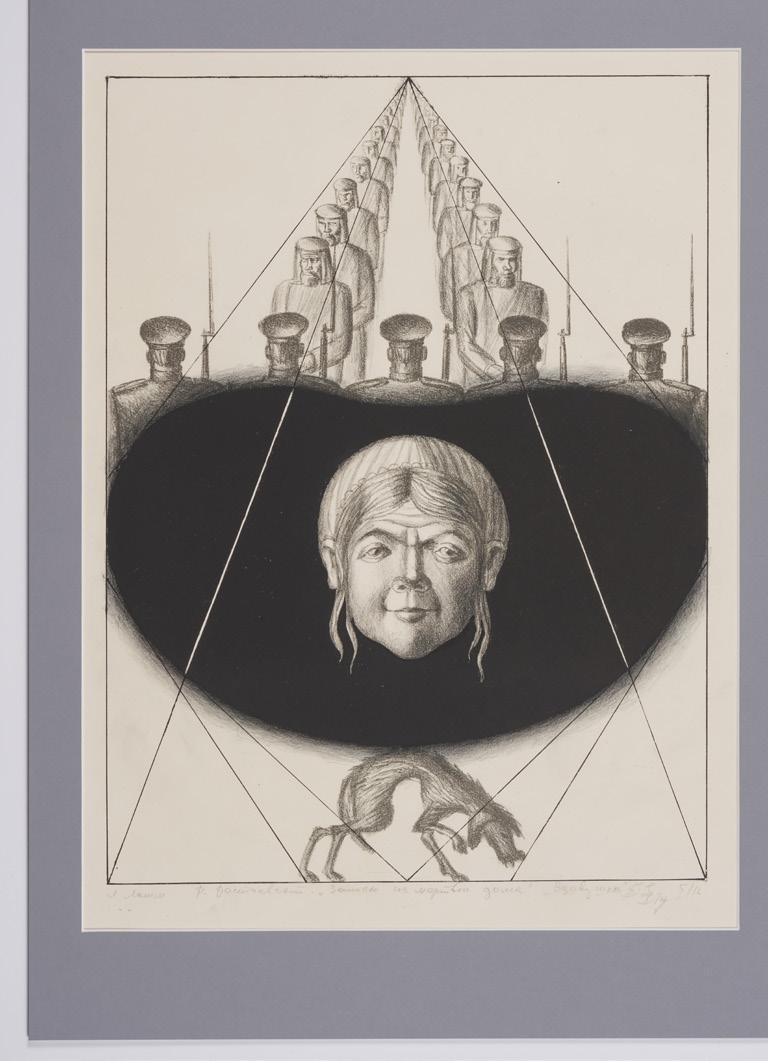

any other agencies to vouch for her husband, they would arrest her and take me away, and she would never see me again (I was five years old). This story echoes the one of Fyodor Dostoevsky who also spent a similar amount of time in a labor camp and wrote one of his most famous books, Notes from the House of the Dead, upon his release. In the prison library, my father found Notes from the House of the Dead and was inspired by the similarities of the story to his own experience. Leonid Lamm made his sketches for Dostoevsky’s book while in Butyrka prison. When my father was finally released, he used these drawings to make lithographs on two stones.” —Olga Lamm

Hear more about the characters and themes found in Fyodor Dostovesky’s novel Notes from the Dead House, which inspired Leonid Lamm’s series of lithographs. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 603

14 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

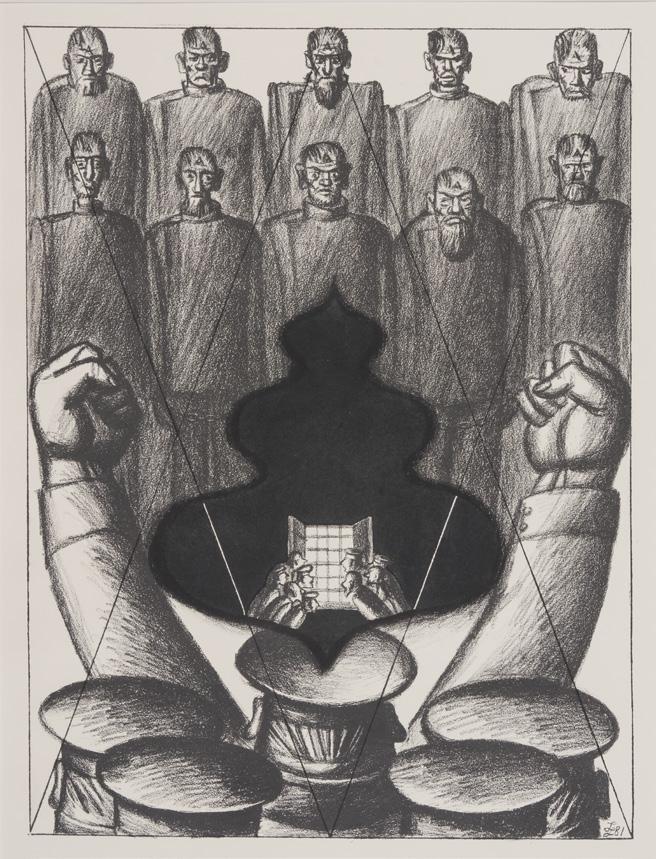

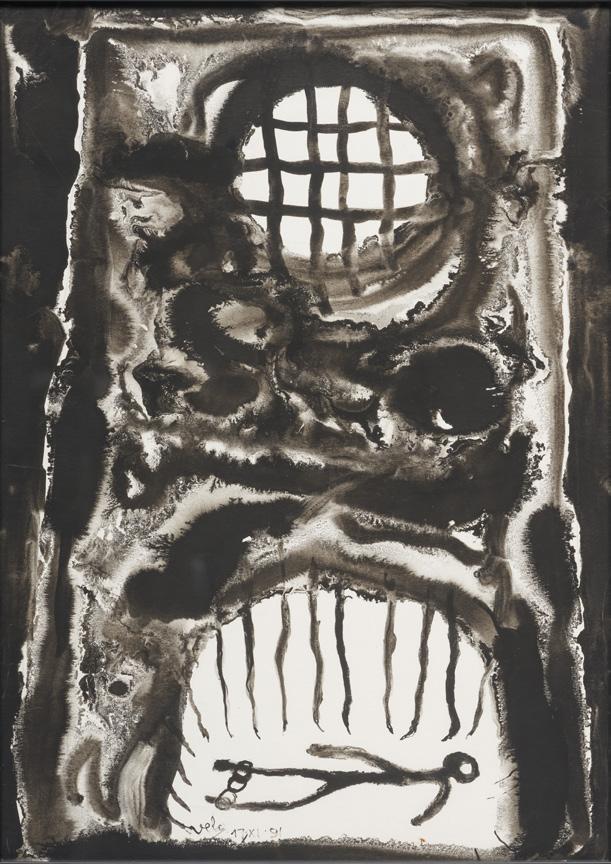

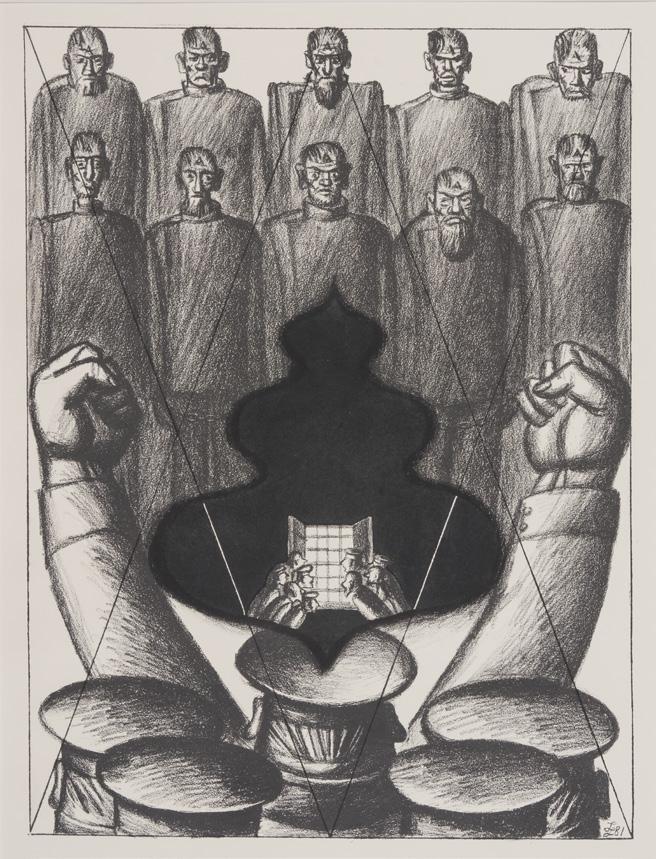

At the top of the composition, prisoners tell the story of how one of them attacked the head of the guard with a knife. He was a terrible person and everyone hated him. The arrested person was punished, and afterwards he died in the

hospital. Along the perimeter of the black hole are the hands of the prisoner with a knife, and in the center of the black hole there is a table where inmates were punished with a whip.

15

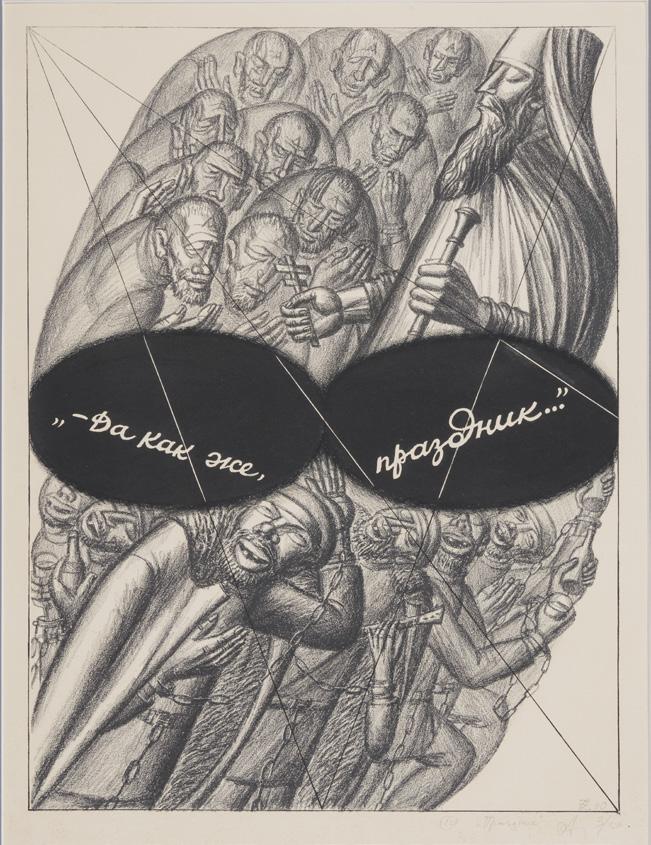

Leonid Lamm, The Head of the Guard, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 11/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Prisoner Gasin, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Prisoner Gasin was drunk and having fun. He paid money to a cellmate who played the violin, and during the performance Gasin repeatedly shouted: “Play, you took the money.” This text is inscribed at the top of the black hole. In addition, we see branded faces of other prisoners with the Cyrillic letters K, A, and T on their cheeks and forehead, denoting their status as convicts. These hallmarks were produced by the authorities and were applied with hot metal.

Leonid Lamm, Prisoner Orloff, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

When Prisoner Orloff tried to escape from a prison camp, he was severely punished by the guards with a line of soldiers armed with wooden sticks, who took turns whipping him. At the top of the composition, we see the conversation of Muslim cellmates with the younger Alei. In the center, we see his bed next to Dostoevsky’s. In the center of the black hole is the figure of a praying Muslim.

Leonid Lamm, Prisoner Sushilov, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

This is a story about cellmate Sushilov, who washed and repaired Dostoevsky’s clothes and cooked his own food. The author tried to give him money. Sushilov was very upset by this and said: “So, you think I am doing this only because of the money, but I, I ... eh!” This text is inscribed in two black holes. Sushilov’s hands move as if he were dividing the black hole. This story suggests that— even in prison— positive human relationships are formed.

Leonid Lamm, Compassionate Widow, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

This story is about a widow who lived near the camp. Some inmates visited her and kept in contact with her for a long period of time. She has become a symbol of kindness and support. This story also mentions a sick and hungry dog.

16 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

17

Leonid Lamm, Prisoner Petrov, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Prisoner Petrov was a very strong and independent person. He tried several times to escape from the labor camp. However, he was caught and severely punished— but he never gave up and dreamed of running away again. Once, he said to Dostoevsky, “You are such a loser, I feel sorry for you.” This text is inscribed at the top and bottom of the black hole. In the upper part of the composition, hardworking inmates are depicted. In the lower part, we see a Siberian winter landscape near Omsk.

Leonid Lamm, Luchka is a Storyteller, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 11/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Luchka shares the story of the murders he committed, always exclaiming out loud:

“I am the king and I am God here!” This text is inscribed in the center of the black hole.

Leonid Lamm, Bath, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 7/20, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Dostoevsky describes the bathhouse as a place where prisoners enjoyed bathing. However, the scene itself reminded him of Dante’s Hell In the center of the black hole is a small figurine of a praying Jew, Isai Fomich. At that time, he was the only Jew in the camp; all the prisoners hated and bullied him.

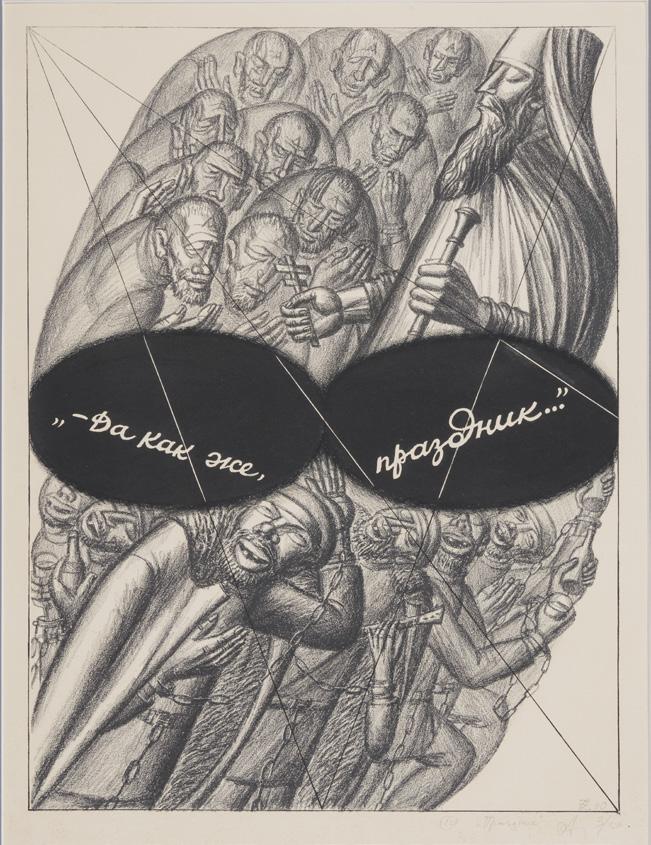

Leonid Lamm, Celebration, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 3/20, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

At the top of the composition, inmates receive absolution. Below, they joyfully celebrate. The text in the black hole reads, “Maybe a holiday.”

18 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

19

Leonid Lamm, Theater, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 16/20, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

This story is about the prisoners who organized a theater in a prison camp. They were actors and musicians. They designed their own costumes; male prisoners played both gender roles and dressed accordingly.

Leonid Lamm, Well-Guarded Hospital, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 11/20, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

This story conveys that the only way to get out of this hospital is to die. The shackles from the prisoner can only be removed after the death has been confirmed by the doctor.

Leonid Lamm, Punishment and Treatment, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Having punished the inmate with a thousand lashes and wooden sticks, the camp authorities took him to the hospital for recovery.

Leonid Lamm, Mentally Ill, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Prisoners watch a mentally ill inmate’s dance. They laugh and rejoice. The text in the two black holes reads: “What joy!”

Leonid Lamm, Emotional Crime and Punishment for It, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

One inmate shared with another the story of how he killed his wife and the punishment he received thereafter.

Leonid Lamm, Great Lent, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

During the celebration of Great Lent, all inmates were escorted to the city near the labor camp to visit the church, wearing a special sign on the back of their prison uniforms.

20 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

21

Leonid Lamm, Prisoners Release the Eagle, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 11/20, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

The prisoners took care of the sick eagle for a long time and fed it. Once the bird got better, he was happily released, while the prisoners exclaimed, “He feels freedom!” The text is placed at the bottom of the black hole.

Leonid Lamm, Anxiety, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

A group of inmates expressed their concern to the prison camp authorities about poor nutrition and a hard life. The security chief threatened to punish them if they didn’t stop complaining.

Leonid Lamm, Escape, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Several inmates tried to escape. They were caught red-handed and severely punished. However, the reaction of other prisoners, written at the bottom of a smaller black hole, was very enthusiastic: “But they ran away!”

Leonid Lamm, The Moral Strength of the Polish Martyrs, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

A group of Polish prisoners tried to stop the ongoing insults and humiliations from the authorities. They were punished with lashes and whips. During the punishment, the Polish mathematics professor did not utter a single word.

22 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

23

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

In the last story, the author is released from the labor camp. He is finally a free person but the black hole is still alive. This black hole

resembles a cross or a flying bird. The text in the last sentence of the Notes reads, “Freedom – New Life.”

24

Creating Space in

Visions of Transcendence:

East and West

Leonid Lamm, Freedom, 1978-1981, lithograph from two stones, edition 5/16, tempera, graphite, and india ink on paper

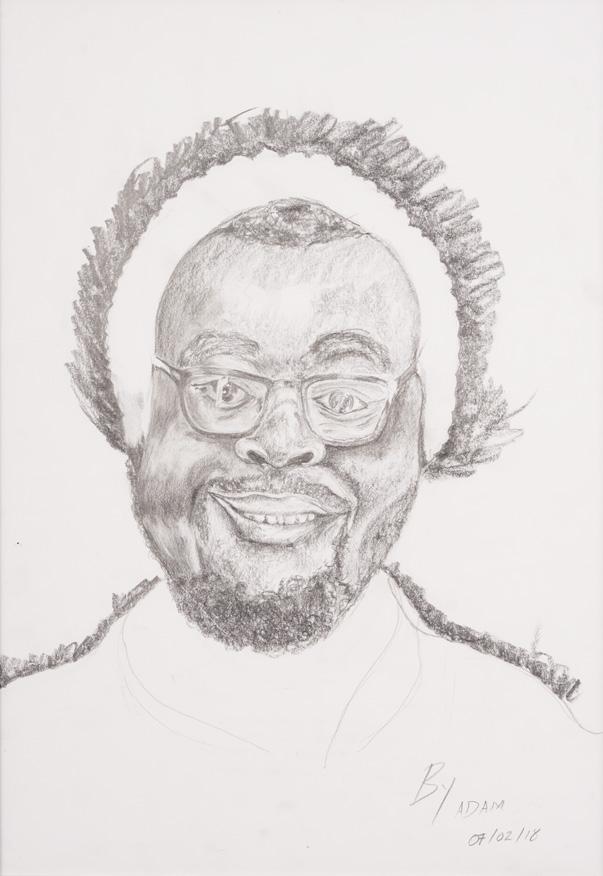

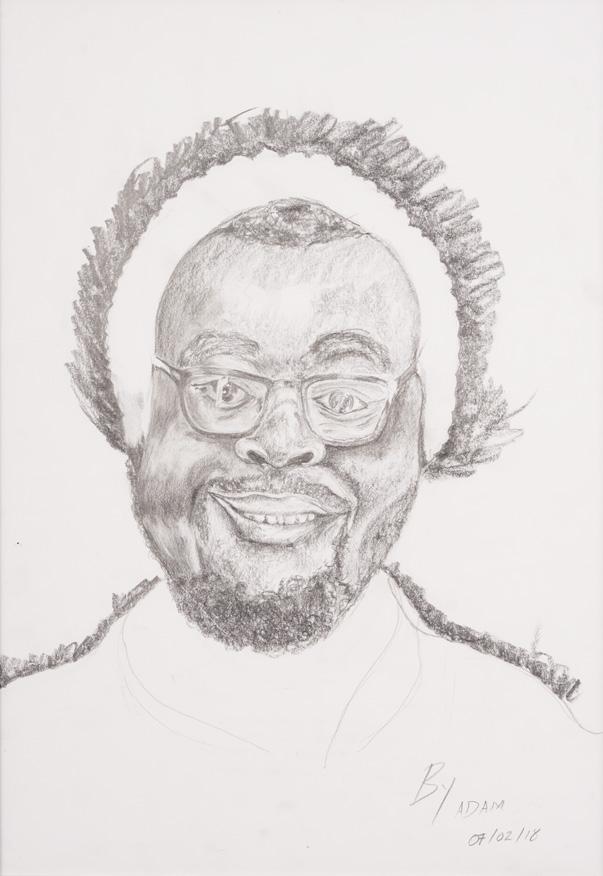

Leonid Lamm, Prison Drawings from Butyrka Prison

Courtesy of Olga Lamm

“In the middle of summer, my mom asked their lawyer to inquire about my dad’s whereabouts, and see if she can be granted visitation rights. The only person who was granted permission to visit my father was their attorney, who also informed my mother that my dad was back in Butyrka prison. With the help of the lawyer she sent two school notebooks, two pencils, and two ballpoint pens for my dad. During the meeting with his attorney, my father wrote a letter for my mom, all the while expressing his gratitude for all the art supplies, stating that he would try to make some drawings. At the end of summer, the lawyer met with my father again, he handed my dad two new notebooks and new pens and pencils from my mom. My dad slipped him notebooks full of drawings of guards and prisoners from his cell for my mom. After learning that there was a very well-known artist in their prison, the chief of Butyrka, Colonel Podrez, asked my father to make signage with slogans for the entire prison. Leonid Lamm agreed because he knew this would allow him to see the entire prison outside of his cell. However, when he asked for art supplies such as paper, paint, brushes, rulers, etc., they responded, ‘We don’t have anything of this sort here.’ To which my father replied, ‘My wife can get me those supplies.’ The chief

said he would think about it. A few days later my mother wrote a letter to Colonel Podrez asking for a meeting with her and another famous unofficial artist, Ernst Neizvestny. About a week later, my mother received a letter granting her and Neizvestny a meeting with Podrez. Shortly after, my mom and her friend met with Podrez at his office. During the meeting they told him about my father’s achievements as an established and respected illustrator and said they’d be more than happy to deliver supplies. To which the Colonel replied, ‘This is not legally possible.’ When Neizvestny asked him, ‘Then how is he supposed to do the work?’ the Colonel replied they could bring whatever is necessary through a drop-off window (for inmates). A few days later my mom delivered all of the materials on her own. Soon after she heard from their lawyer that my father was very grateful to have received the supplies. After collecting several notebooks with drawings, and watercolors on paper, my mother began showing them to their friends who were artists, writers, musicians, directors, etc.

Everyone was very impressed that he was able to illustrate his life in prison. After receiving such a response, she sent my dad additional supplies.” —Olga Lamm

Bloomberg Lookup Number: 636

25

Hear the story of how Leonid Lamm’s wife fought the odds, and some prison guards, to provide her husband art supplies while he was incarcerated in Butyrka prison.

Leonid Lamm, Punishment Cell, 1974, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Kukhiev - Briber; Gulkhin - Thief; Timofeyev - Briber, 1975, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper

of Olga Lamm

26 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Leonid Lamm, Prosecutor - Pokhomov; Assistant Prosecutor - Nagaev; Gang Leader - Zhukhov; Embezzler - Karoyan; Hooligan - Volkov, 1975, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

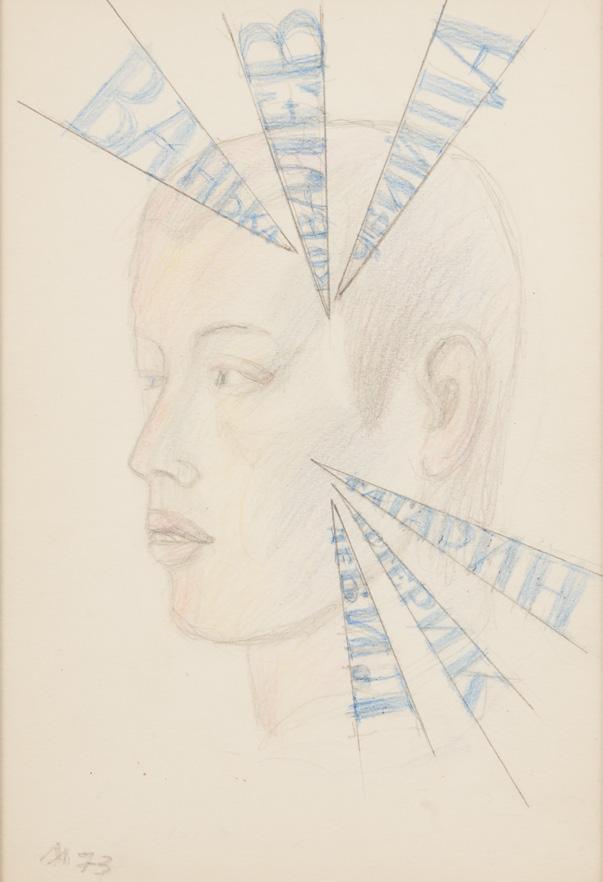

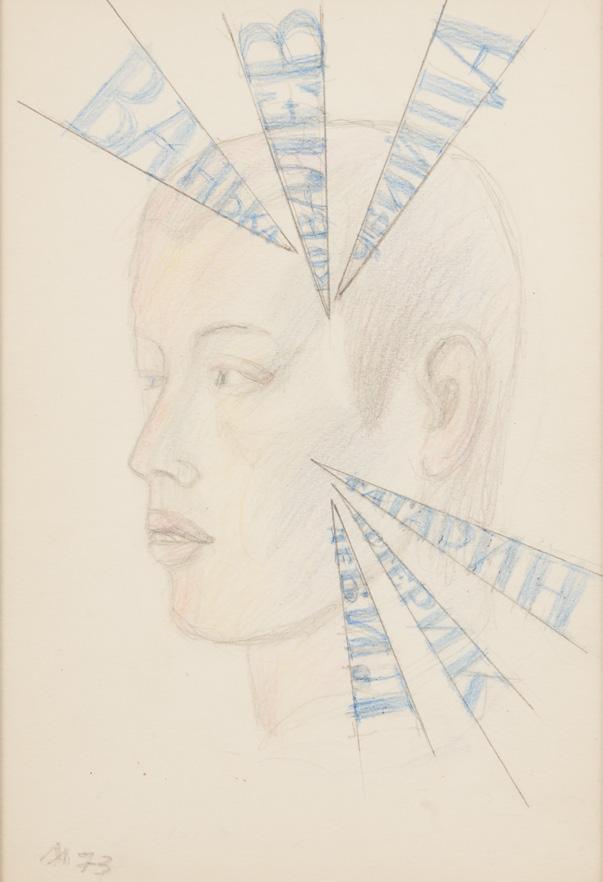

Leonid Lamm, Three, Three, Three, 1973, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Courtesy

27

Leonid Lamm, Kunstkammer (The Search of My Home), 1975, Butyrka Prison, watercolor and ink on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Butyrka - Prison Yard #1, 1974, Butyrka Prison, watercolor and colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

28

Creating Space in East

West

Visions of Transcendence:

and

Leonid Lamm, BUTYRKA Prison - CELL #301, 1975, Butyrka Prison, watercolor on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Assessor - Gooton; JudgeBrizitsky; Assessor - Gooton; - Nikonov, 1975, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Ivan (Murderer), 1973, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Avakhumov Ignat - Smart, Sly, Scammer, 1973, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

Leonid Lamm, Nikolai Gulyaev - Punk, Moron, 1973, Butyrka Prison, colored pencil on paper Courtesy of Olga Lamm

29

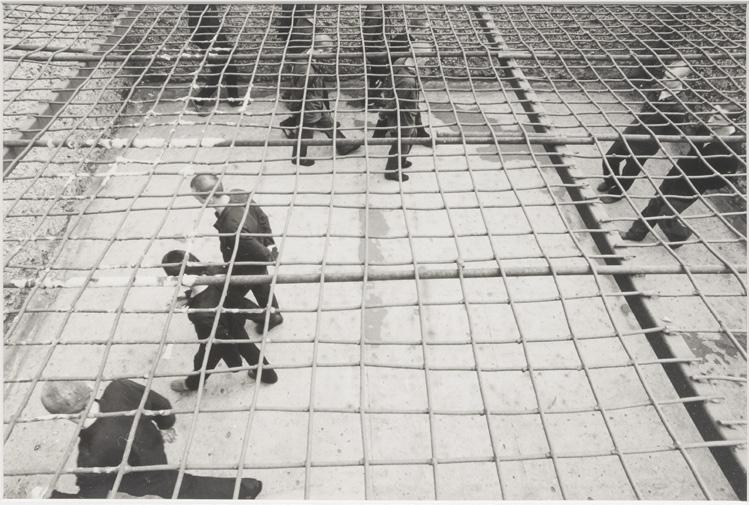

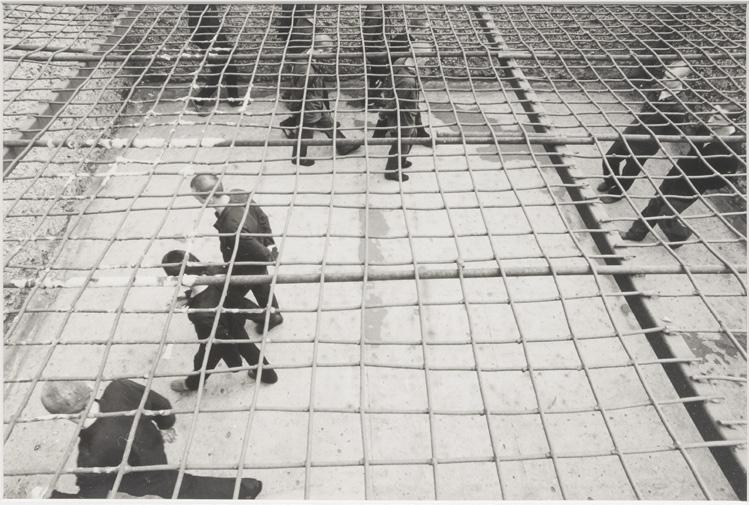

Shepard Sherbell

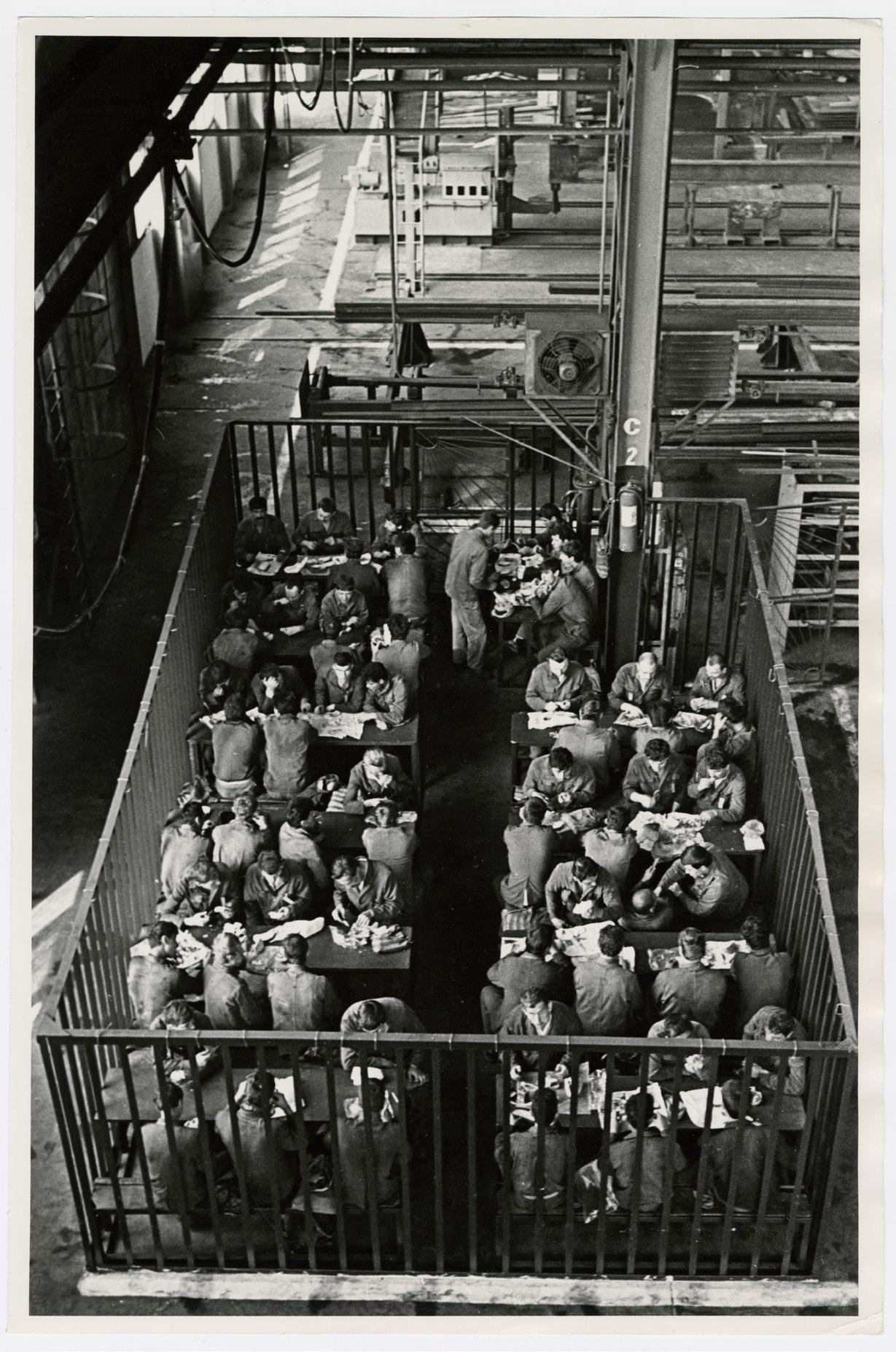

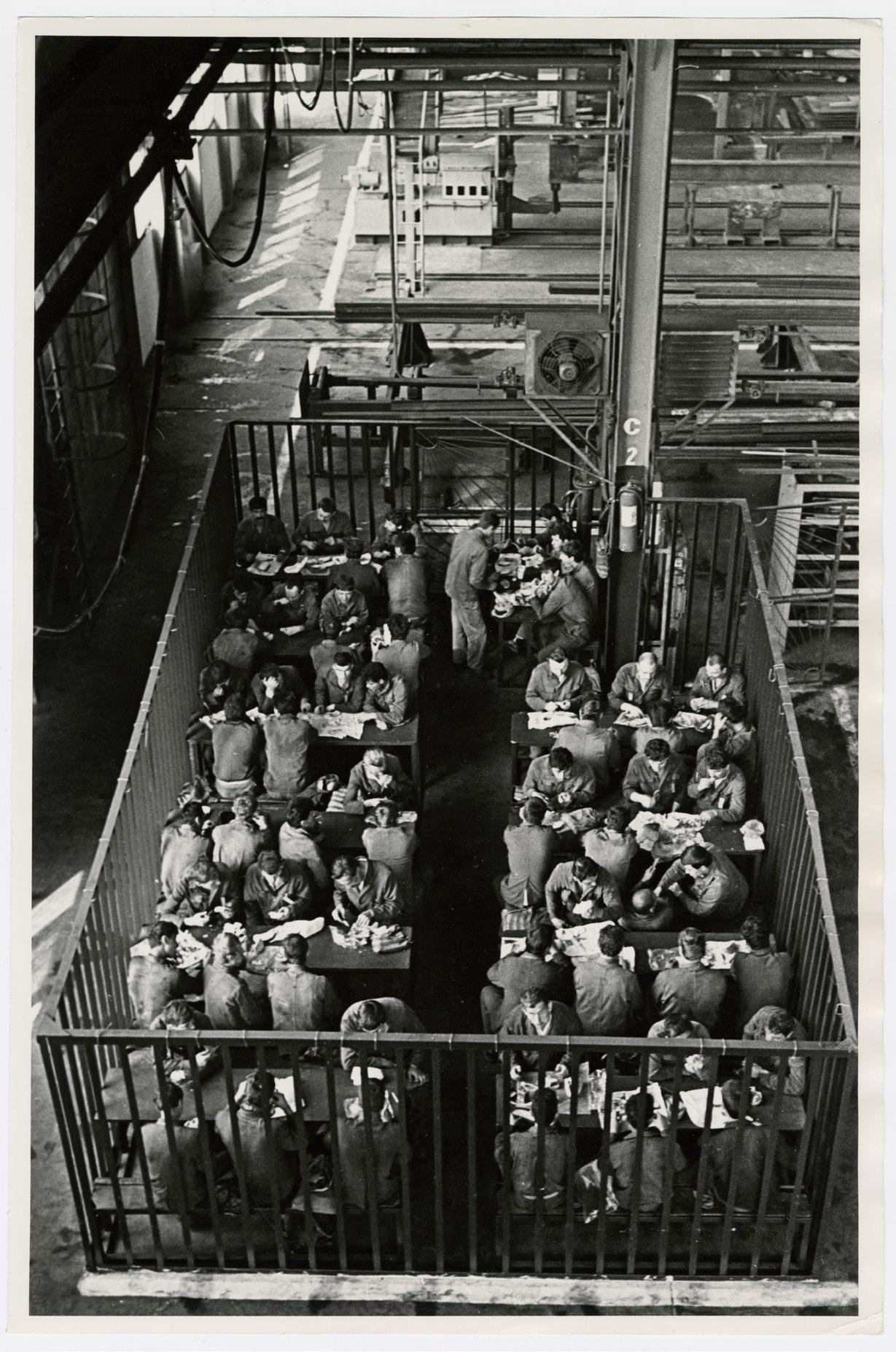

On assignment for the German weekly Der Spiegel, Shepard Sherbell traveled throughout the Soviet Union and post-Soviet republics from 1990 to 1993 photographing people during the Union’s dissolution and the early years of the Russian Federation. Having unrestricted access to subject matter, he showed the lives of mothers, miners, farmers, children, and prisoners during the transition from communism to capitalism. This series of images presents the harsh reality inside youth prisons and labor

camps, depicting boys marching through the snow, boys working in a prison factory making handbrake cables for Lada automobiles, and the relief of after-lunch smoke breaks despite the freezing weather outside. One of the images shows the young prisoners from Yeletz Maximum Security Prison on the prison yard, caged with a metal grate from above, during which time they were not allowed to look up at the sky. They were only allowed one hour a day to exercise in fresh air.

30 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Shepard Sherbell, Labor Camp for Boys, Dimitrovgrad, 1992, gelatin silver print Collection Wende Museum, gift from the Goldman-Sonnenfeldt Family

31

Shepard Sherbell, Untitled, 1991-1992, gelatin silver print Collection Wende Museum, gift from the Goldman-Sonnenfeldt Family

Shepard Sherbell, Untitled, 1991-1992, gelatin silver print Collection Wende Museum, gift from the Goldman-Sonnenfeldt Family

Shepard Sherbell, Yeletz Maximum Security Prison, 1991, gelatin silver print Collection Wende Museum, gift from the GoldmanSonnenfeldt Family

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space

32

in East and West

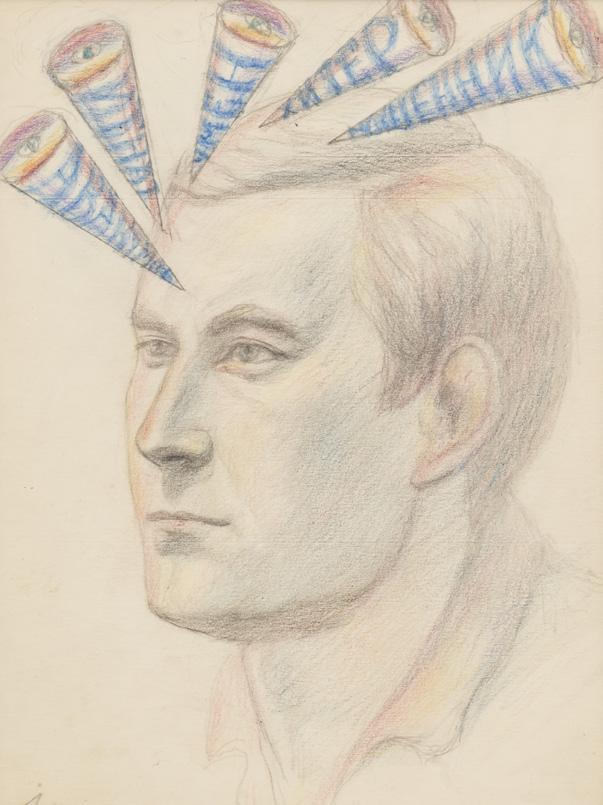

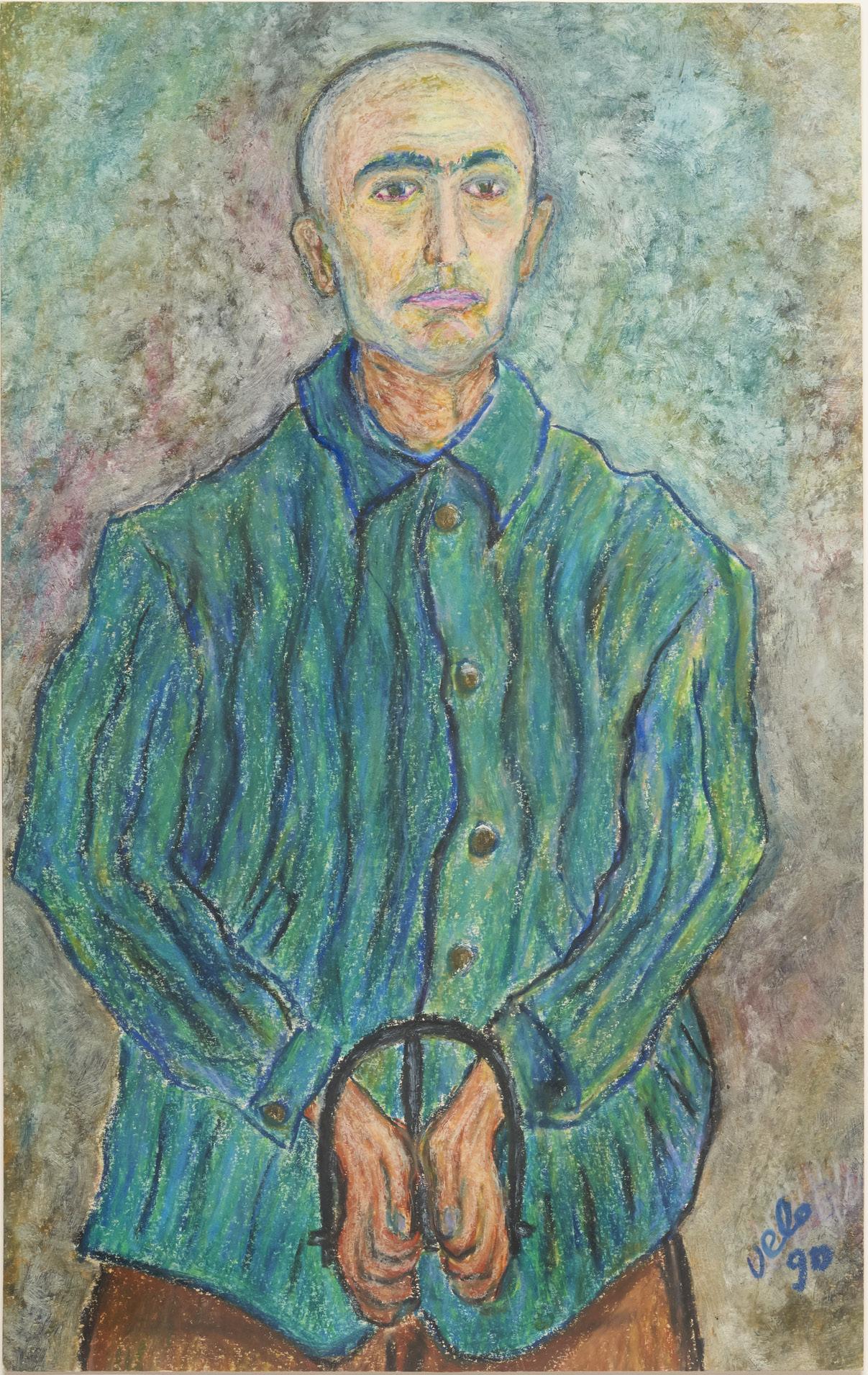

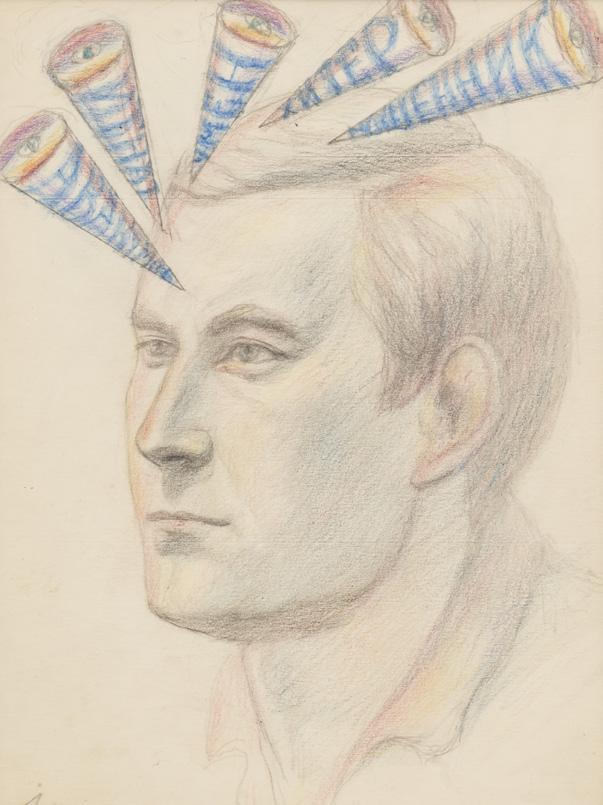

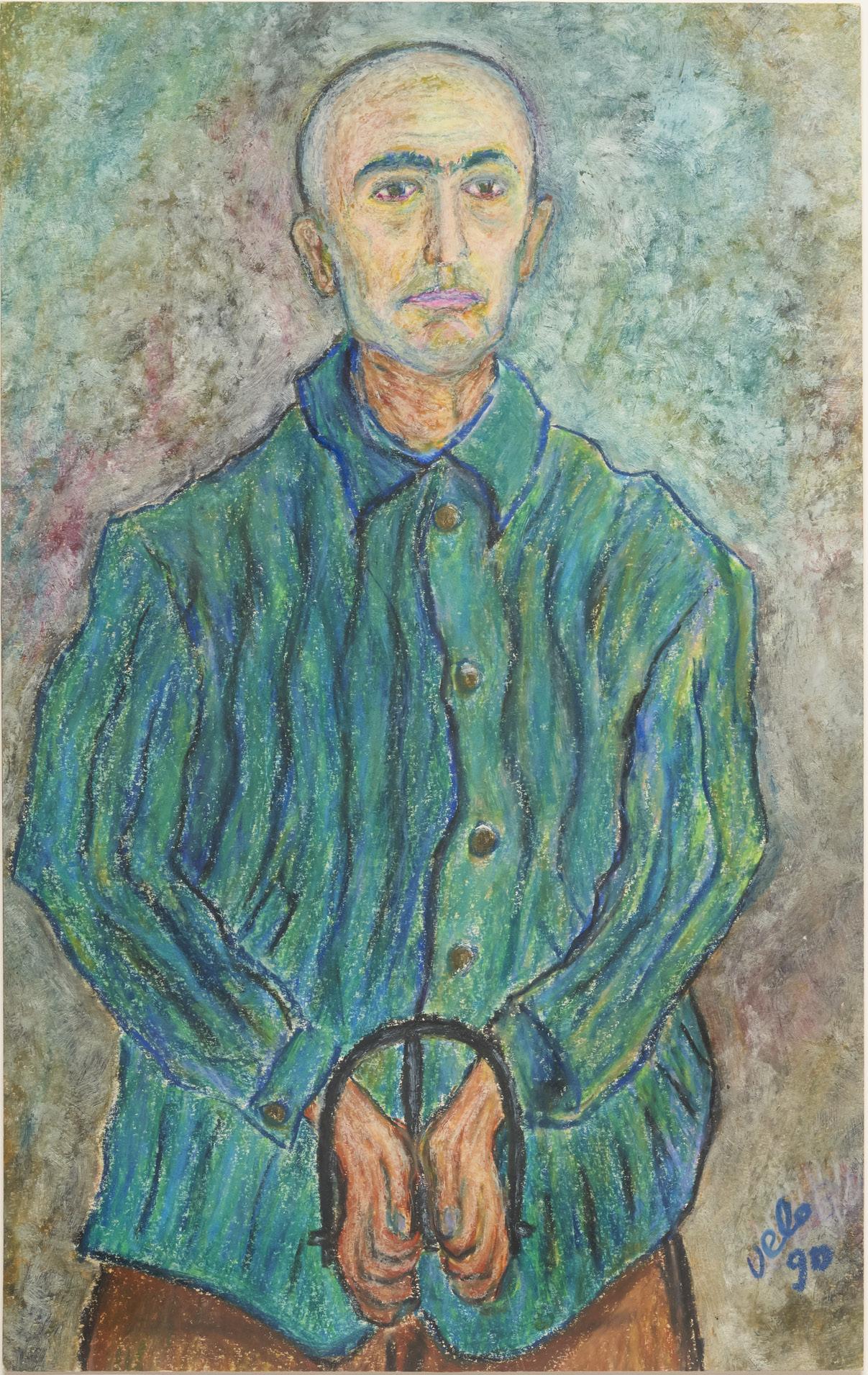

Maks Velo, The Prisoner (Self-Portrait), 1990, crayon on paper Collection Wende Museum

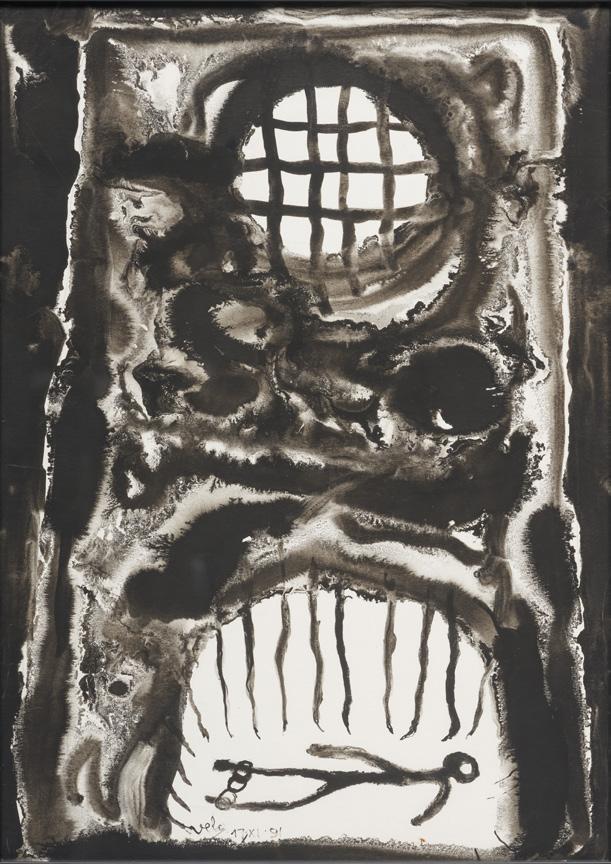

Maks Velo

This series of works by Albanian painter Maks Velo reflects on his personal experiences as a political prisoner in communist Albania. In 1978, Velo was sentenced to ten years in a prison camp for “agitation and propaganda” under communist leader Enver Hoxha. Among other things, Velo was accused of contravening the state-sanctioned style of socialist realism by producing artworks inspired by modern artists like Amedeo Modigliani, Georges Braque, and Pablo Picasso. As a result, almost all of Velo’s paintings were destroyed, and his art collections were either stolen or burned. In this unique series, created after his release in 1991, Velo shared, in his own words, “the violence of investigation, and the violence of life in prison.” Tens of thousands of Albanians were imprisoned in forced labor camps during the Cold War period. Examined together, Velo’s drawings offer a harrowing portrayal of persecution and the struggle for justice. The Wende Museum serves as a research repository for the historical witness videos collected by the Albanian Human Rights Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to collecting, filming, and preserving the testimonies of Albanians, like Maks Velo, who were politically imprisoned or interned from 1944-1991 during Albania’s communist regime.

33

Clockwise from top left

Maks Velo, The Cell, 1991, ink on paper

Maks Velo, The State’s Pressure on People, 1992, ink on paper

Maks Velo, The Dictatorship, 1991, ink on paper

All collection Wende Museum

Jared Owens

“The most prominent symbol in these works is the actual figure of the human being, the shadow figure. And that was sourced from the Brookes slave ship diagram that was used to abolish slavery in the 1800s. So, what I’ve done with it is they were laying down, now they’re standing up, right? But at the same time, in standing them up and giving them dignity, I’m also taking away their identity. And even in trying to do so by making them shadows, some of them have faces, no matter what. They have individuality that can’t be stripped from them. So, I always felt like the symbolism of that is very strong. There’s also the use of soil that I sent home from the prison where I was incarcerated over ten years ago. And I started thinking about conceptual elements to send home that would be symbolic of mass incarceration in the crossroads of the state. I started to pretty much grab whatever I could that was around inside the prison that I thought could be made into an object or

be incorporated into objects once I was back in society. Soil is one of the things that I use all the time in my art. I like it to be present because it comes from a place that I, a.) have no desire to return to, and b.) cannot get any more of that material. So, the material is like gold dust to me because thousands of people have suffered on it, sweat on it, bled on it. A lot of the soil is conceptually rich in the nutrient density of suffering. I want people to see the marginalization visualized in front of them. So, the message would be, What can we do as a society to decrease the amount of that terrible thing? How do we eradicate it? And that’s the age-old question. And I just want to always have that question presented in art. I don’t want to make art just for art’s sake. I think that it should be a recognition of social ills that need addressing. And I think that it has to be present in art all the time. I love pretty pictures too, but I think that art should be thought-provoking.”

—Jared Owens

34 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Bloomberg

Hear from the artist, Jared Owens, about the symbolism at play in his Series 111 and the ways in which the number 111 followed him in the lead-up to his incarceration.

Lookup Number: 861-864

clockwise from top left

Jared Owens, #9, Series 111, 2022, mixed media on panel, soil from prison yard F.C.I. Fairton, lino printing

Jared Owens, #6, Series 111, 2022, mixed media on panel, soil from prison yard F.C.I. Fairton, lino printing

Jared Owens, #8, Series 111, 2022, mixed media on panel, soil from prison yard F.C.I. Fairton, lino printing

Jared Owens, #11, Series 111, 2022, mixed media on panel, soil from prison yard F.C.I. Fairton, lino printing

All courtesy of the artist

35

Marlen Spindler

Spindler’s painting was made while serving fifteen years in a psychiatric institution in the Soviet Union. The inspiration of his work lies in his passion for Russia, its nature, and its orthodox icon paintings and frescoes, illustrated in this painting that includes

the central biblical figure of King Solomon. It contains interesting and unique symbols of human life, magical and mysterious figures and creatures believed to represent matters of the soul.

36 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Marlen Spindler, King Solomon, 1972, watercolor on paper tablecloth Courtesy of Alexander Smukler

Stanislav Molodykh

This unique painting of a Soviet mental asylum depicts a remarkable mixture of people. Some appear mentally or physically ill, while others are merely reading a book or playing the guitar— a possible reference to the fact that under Secretary General Leonid Brezhnev, dissident artists and intellectuals were regularly confined in mental institutions. Stanislav Molodykh was a patient in this asylum; he voluntarily committed himself to overcome his alcohol addiction. He

added a self-portrait as the seated man facing the viewer in the lower left corner. The religious mural in the back indicates that the asylum was housed in a repurposed church building. The black cat in the foreground might be a reference to Mikhail Bulgakov’s famous novel The Master and Margarita, in which the devil, always accompanied by a big black speaking cat, compares the Soviet Union with a mental institution.

37

Stanislav Molodykh, The Asylum, 1982-1995, oil on canvas Collection Wende Museum

Solomon Gershov

Solomon Gershov’s work was often inspired by Biblical subjects and themes of Jewish festivities. Additionally, many of his works reference dance and music. Both of these elements can be found in this work depicting someone playing a shofar, a ram’s-horn trumpet used in Jewish religious ceremonies. The work was made after Gershov’s release from the

Vorkuta gulag, while he was in Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg). Gershov is known for the improvisational character and spontaneity of his work, in which he draws from the experience of his culture. According to Gershov, the artist should “soar up to the sky and cry out to the whole world about its strangeness and imperfection.”

38 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Solomon Gershov, Shofar, 1983, gouache on paper Courtesy of Alexander Smukler

Mihail Chemiakin

Being forced into a psychiatric institution and then exiled from the Soviet Union in 1971, Mihail Chemiakin is known for his nonconformist, surrealist iconography and use of color and space, which are evident in this portrait of Russian tsar Peter the Great. In 1967, Chemiakin founded the St. Petersburg Group, which

became one of the most well-known nonconformist art communities in the Soviet Union. Chemiakin and his group would develop “Metaphysical Synthetism,” a manifesto dedicated to creating new forms of icon painting based in religion, making his work unacceptable to Soviet authorities.

39

Mihail Chemiakin, Peter the Great, 1979, oil on canvas Courtesy of ABA Gallery

Boris Sveshnikov

In 1946, Sveshnikov was sentenced to eight years in Siberian labor camps on charges of anti-Soviet propaganda. Sveshnikov made artwork both during and after his incarceration; this painting dates from after his release. Sveshnikov expresses his experiences in the camp through dream-like surrealism, addressing themes of loneliness, surveillance, and death. In the 1970s, he tended to adopt a color palette of violet and blue tones along with a pointillist

technique, as seen in this work. His artwork is intricate with patterns and suggested forms including bird heads, feathers, shells, and human profiles. Though Sveshnikov experienced harsh treatment in the camps, he considers his work to be personal and apolitical. “What I painted at home I did for myself . . . All of my works are dedicated to the grave.”

—Boris Sveshnikov

40 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Boris Sveshnikov, Faces and Butterflies, 1980, oil on canvas Courtesy of KGallery and Khodorkovsky Family

Lev Kropivnitsky

In 1946, Lev Kropivnitsky was arrested on a charge of belonging to an anti-Soviet terrorist organization and sentenced to ten years in labor camps in Komi and Kazakhstan. He was discharged in 1954 and rehabilitated in 1956. After his release, he started to paint in an abstracted impressionist style, as shown in this painting. Non-figurative painting helped Kropivnitsky in explaining and comprehending his feelings and experiences beyond visual reality.

“Non-figurative painting gave me the oppor tunity to be closer to reality, to explain the essences of things, to comprehend everything important that we can’t perceive with our five senses. I tried and am trying now, on the basis of what we have lived through and experienced, to create a painting form suitable to the spirit of our times and the psychology of our century.”

—Lev Kropivnitsky

41

Lev Kropivnitsky, Portrait, 1960s, oil on board Courtesy of KGallery and the Khodorkovsky Family

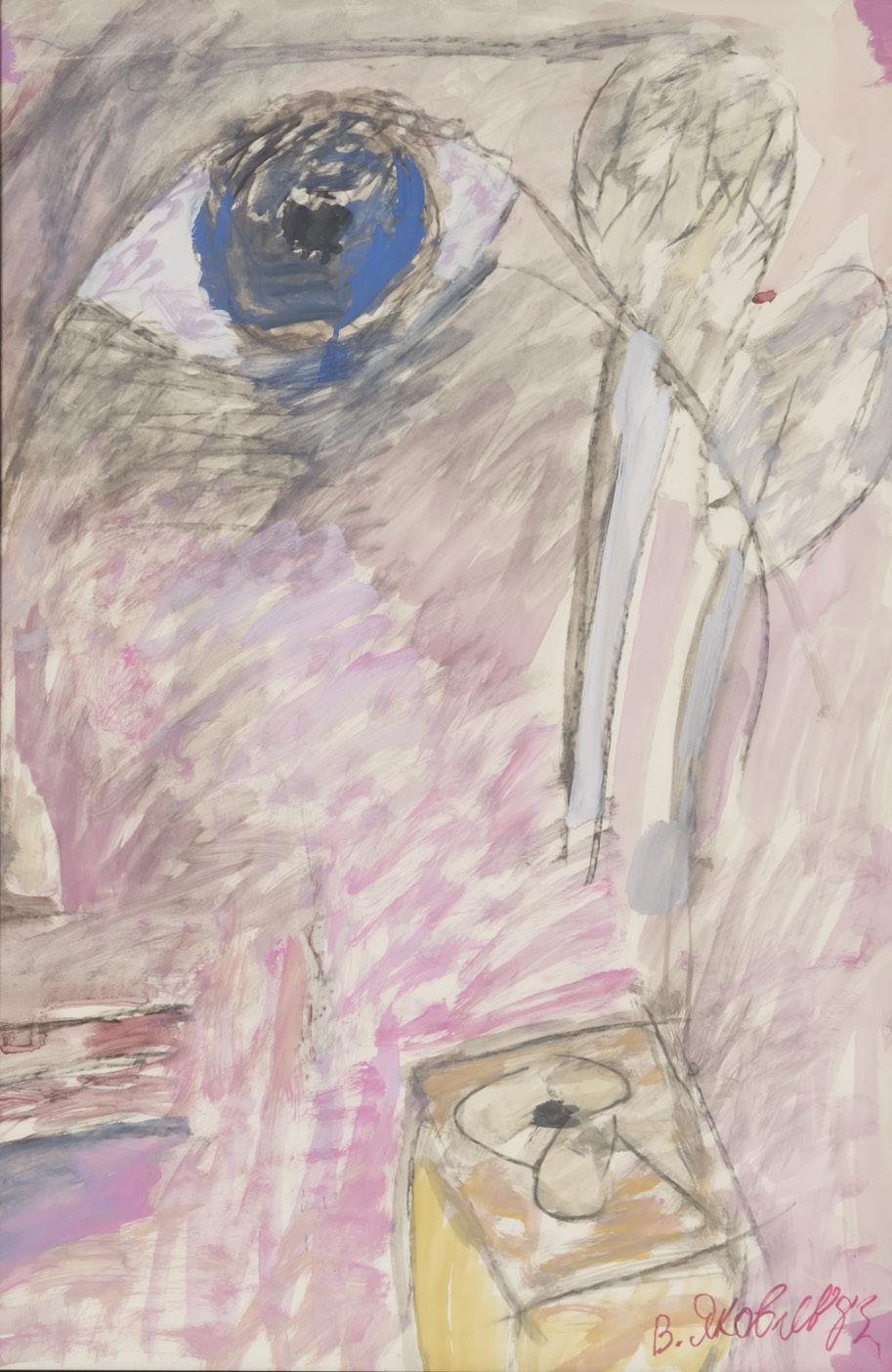

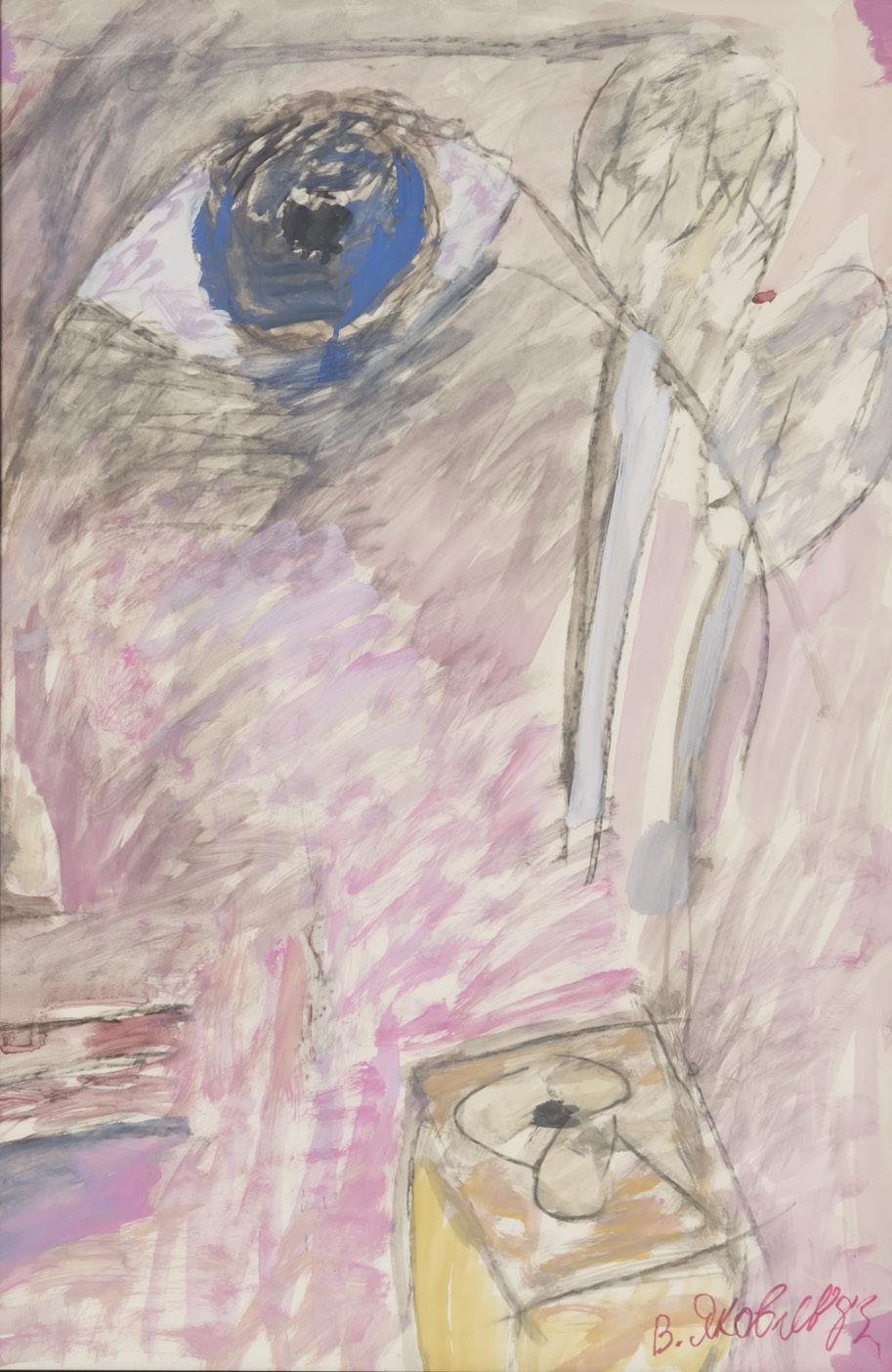

Vladimir Yakovlev

Vladimir Yakovlev, Composition with Flower and Eye, 1983, gouache and watercolor on paper Courtesy of KGallery and the Khodorkovsky Family

Vladimir Yakovlev’s favorite subjects include fish, landscapes, portraits, and flowers. Both his portraits and flowers are often created solely from memory, revealing his understanding of his world, defined by beauty, through symbols of humanity and nature. With compositions informed by German Neo-Expressionism, Yakovlev uses tools of “deformation, the flattening of form, the expansiveness of color, and experimentation of perspective.” These

tools allow his artwork of simple objects to be highly emotive and harmonic. Yakovlev lived in a neuropsychiatric boarding school in Moscow in the final years of his life.

“I can convey everything in my painting: movement, love, shouting. Through color, I try to convey the cry of unharvested wheat. But it is difficult to convey human thought. My painting is not abstract, not realistic, it is decorative. I love beauty.” —Vladimir Yakovlev

42 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Vladimir Yakovlev’s symbolic flowers, often fragile and falling, invoke metaphors of beauty, loneliness, and suffering. These themes ring true to life, especially in his confinement to Soviet psychiatric hospitals from 1984 until his death in 1988. Being nearly blind and living in isolation under the harsh conditions in these psychiatric institutions gave Yakovlev a “firm grasp on the intangible” and a clearer perception of life’s harmony.

“ There must be the energy of life within a painting. It must give a feeling of organization to one’s life, work, a call to order and purity. In color, there should be tenderness, it should convey the dynamics of life, not its emptiness, give something fresh, true, and convey it with a single brush stroke . . . I was told: Your flower is falling. But the life of a flower is within its fall. If not, the flower is dead. Falling is life.”

—Vladimir Yakovlev

43

Vladimir Yakovlev, Two Flowers, 1980s, gouache on paper

Courtesy of KGallery and Khodorkovsky Family

Gil Batle

Carved Ostrich Eggshells

“My eggs are about prison life meshed with prison memories. The eggs are my journey. I call them the Wanderer. The wanderer is me. I’m looking for a home. I have a house, but I don’t have a home. I’m housed, but I’m still homeless. An egg I finished right before the show is called Common Swift. The common swift is a bird. And this bird spends 90 percent of its life flying from country to country. It can’t land in the water, so it spends most of its life in the air. It sleeps, it mates, it eats in the air. It doesn’t have a home either. It can’t have a home. And so that egg shows the Wanderer passing through prison, passing through the

island, past the island, a beautiful island, and it ends. Well, the eggs don’t end or begin, but on its final stop . . . I carved out a homeless person with the head of a common swift, the bird sitting with the homeless. He’s content. He’s not in a prison cell, but he no longer has to fly anymore because he realizes that his home is here. And I need to realize that, too. It’s not out there, it’s here. So wherever I go, I am also reminded that it’s better than a prison cell. I don’t care where I am. I could be sleeping in a dark alley next to a homeless guy. It’s better than a prison cell. I am free and I am alive.”

—Gil Batle

Bloomberg Lookup Number: 799

44 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Gil Batle, about how he reflects on prison memories through carving ostrich eggs.

from left

Gil Batle, Kite Deck, 2017, carved ostrich egg shell

Gil Batle, Refuge, 2019, carved ostrich egg shell

Gil Batle, Time Killer, 2016, carved ostrich egg shell

All courtesy of the artist and Ricco/ Maresca Gallery

45

Gil Batle, Queens, 2016, carved ostrich egg shell Courtesy of the artist and Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Gil Batle, Prison Weapons

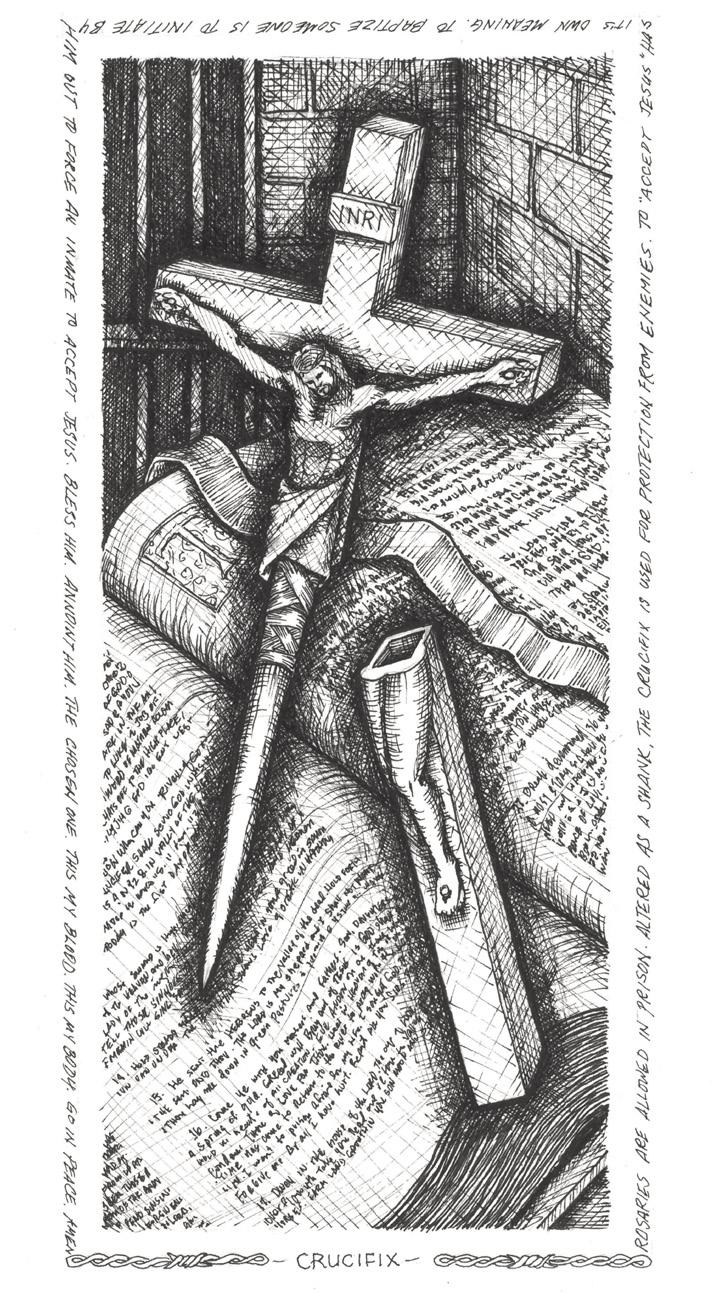

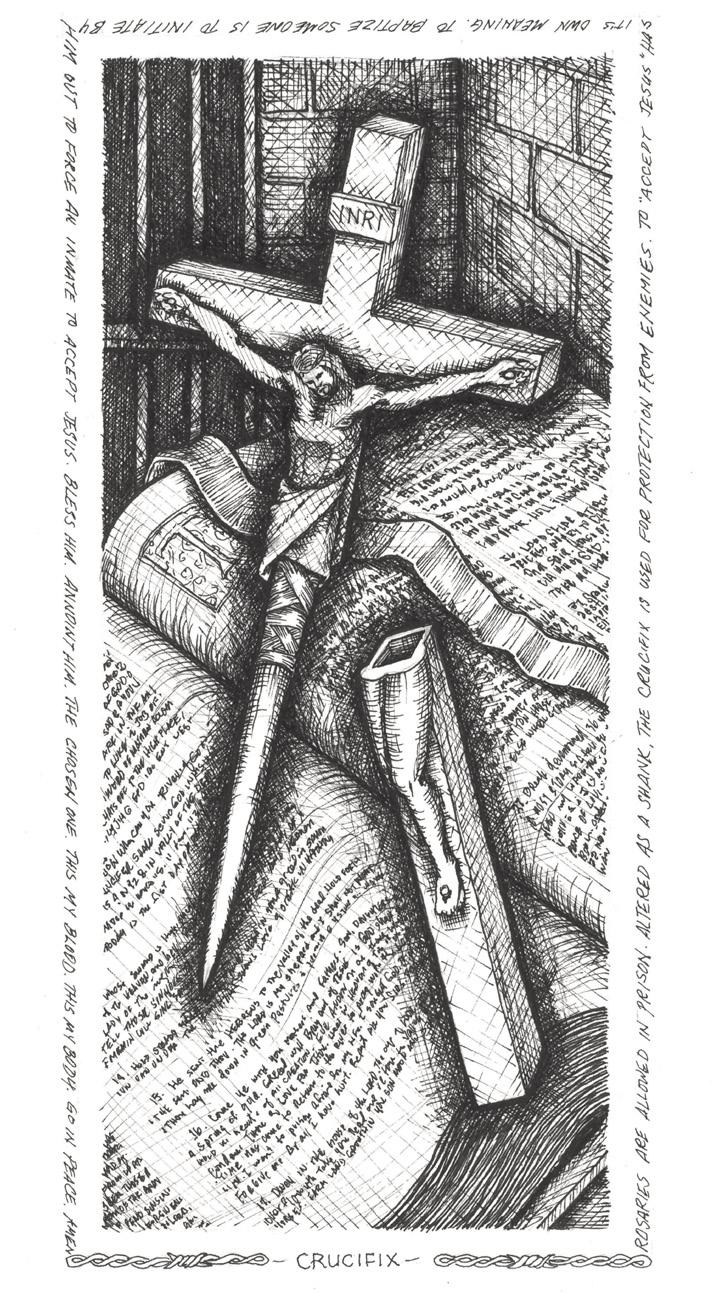

Gil Batle, Crucifix, 2018, ink on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Ricco/Maresca Gallery

“In prison, they have what they call ‘sweeps.’ The guards would pick a random day, and they come in and say, ‘Out. Out of the cell.’ They kick you right out. What they look for is contraband: cigarettes, drugs, whatever. Stuff you’re not supposed to have. One of the things that I thought was really interesting that they look for are crosses. Crucifix crosses. Matter of fact, on a sweep in Donovan State Prison near San Diego, the first sweep was in a dorm setting. We were watching them throwing stuff out of the dorm onto a pile. Whether it be books, razors, pencils anything longer than, I don’t know, four, three inches. One of the things I noticed, when I first got there, were crucifixes. I said, ‘Oh, man, that’s fucked up. Why the

crosses? Why? The guy’s religious. He’s got nothing else left in his life. He’s got religion.’ As we’re sitting there, the guards each take a cross. Some of them are little plastic ones, the rosaries—they don’t mess with those. Some are the bigger ones, the ones they hang up on their walls. Some are handmade, some are given by family members to pray. The guards pile them up into whose bunk they got it from. And then they pick up the crucifix, and they try to pull it apart. Every so often, they are able to pull apart the crucifix and a little dagger comes out. You pull the cross, and it exposes a blade. It’s small, but it can do a lot of damage, especially if you’re holding a guy down and you’re cutting them up.”

—Gil Batle

46 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

“The toothpicks are a type of shank, usually made with toothbrushes. They don’t allow the long toothbrushes that we have—the ones we buy at the store. They give you state issues. What the prisoners do is they take the handles and shape them. I’ve seen some shanks where they melt it. So, you get a disposable razor. They give you these in prison. They give it to you with your soap, your toilet paper, your socks, your

underwear, and towel, and whatever. This is one of your state issues. They give you one, and then they mark your name off. And then, every Sunday they come and collect them. So what they do is they ‘click, click, click,’ and they take off the blade and attach it to the toothbrush, and then take bedding and wrap it around. It’s called toothpick.” —Gil

Batle

47

Gil Batle, Tooth Pick, 2018, ink on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Ricco/Maresca Gallery

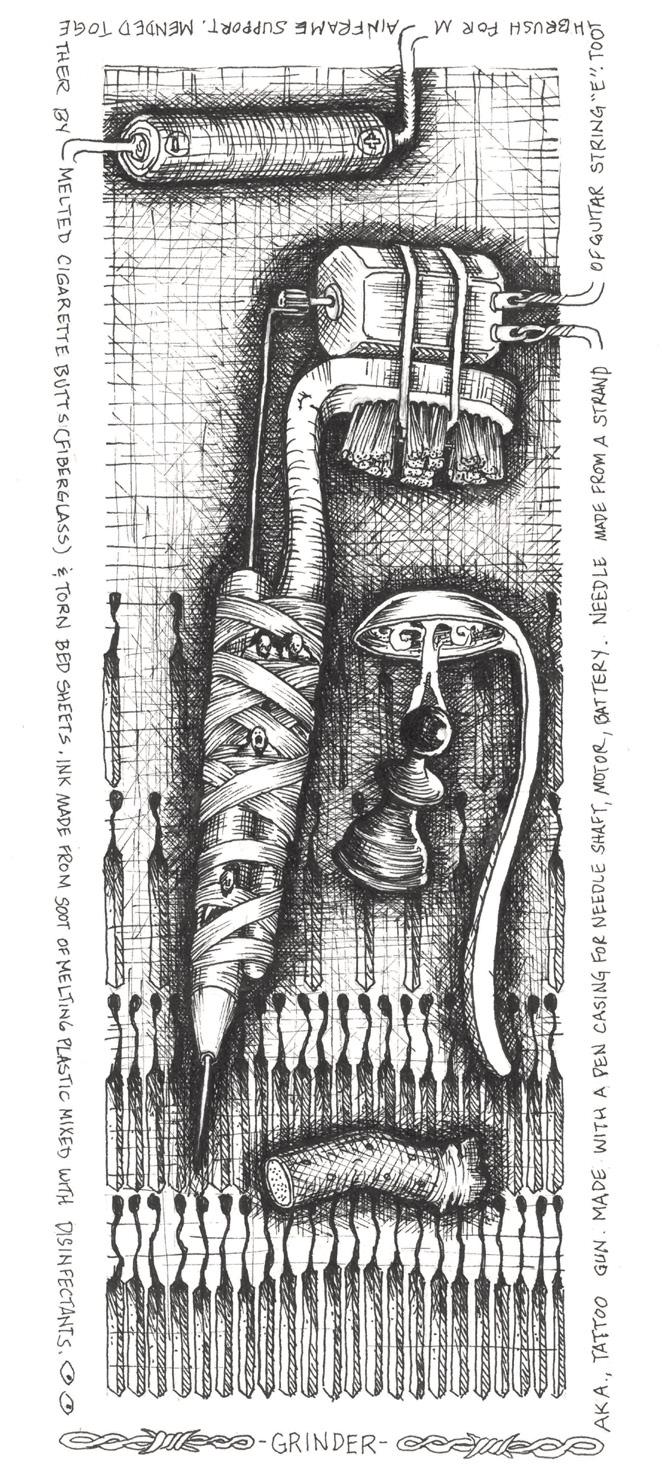

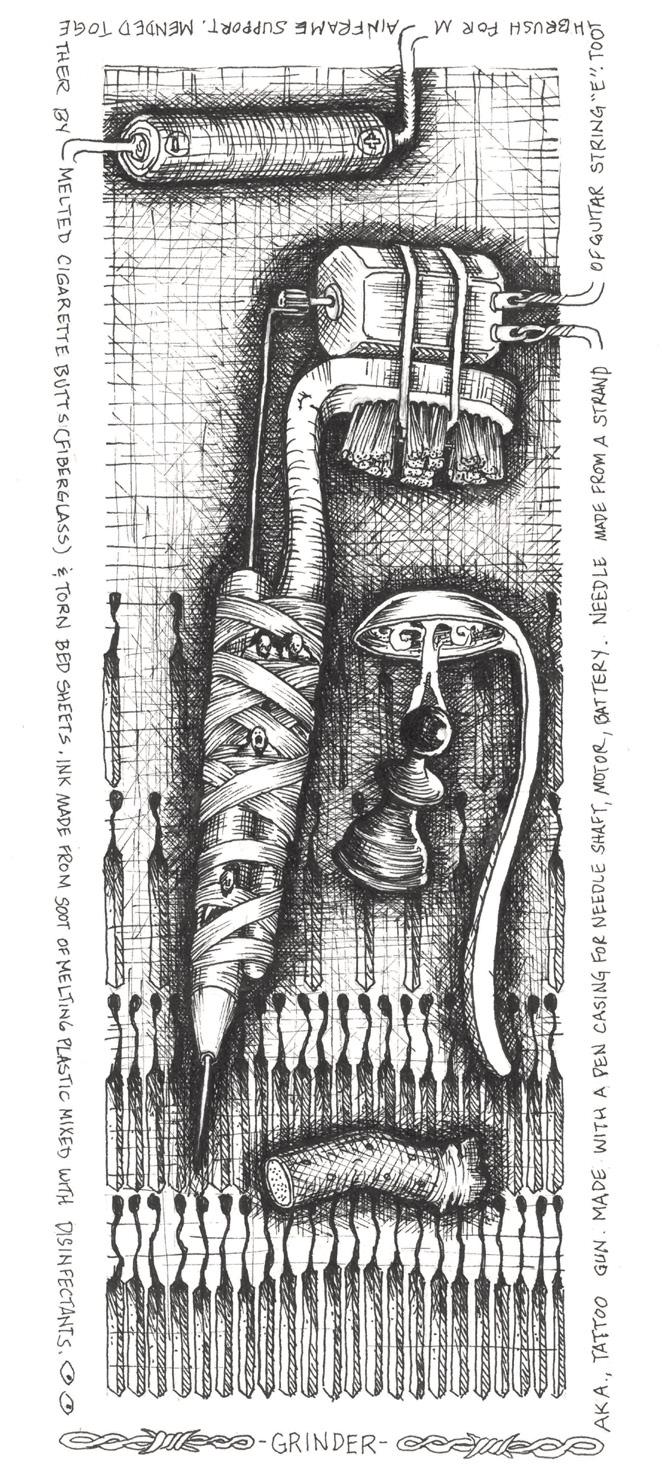

Gil Batle, Grinder, 2018, ink on paper Courtesy of the artist and Ricco/Maresca Gallery

“In prison, I learned the trade of tattooing. If you get caught with tattoos in prison, you can serve more time. You’re not allowed to get tattoos in prison because you are state property, so they charge you with damaging state property. If you get caught with a tattoo gun, it’s even more time. So, you have to be discreet on making a tattoo gun or even be in possession of one. The main material to make a tattoo gun is the motor. You need a motor from anything that spins. Back in the ’90s, it was cassettes. Cassette players have a little motor in it. Then, there’s a toothbrush. You take the toothbrush and you melt the neck into an L shape. You rest a motor on it with the spindle and tie that on with either bed sheeting or tape, if you saved enough tape. Then you get a shaft. It’s usually a Bic pen, and you take out the ink cartridge so you have a hollow shaft, and attach it to the spoon or the toothbrush with the motor sitting on the top. The hardest of all the parts to get is a guitar string size E. No other guitar strings are going to work. You bend the string into an L shape. You stick it down the shaft of the Bic pen, which is attached by tape or string to the toothbrush.

And then you take that little L shape, so there’s the L-shaped guitar string on the other end. Down there is the tip that goes into your skin. So you attach that to the sprocket so as it turns, it’ll turn with the sprocket, and the needle will go up and down. And then, you can get wires from the same place you stole the motor from. You can take the two wires and get an ordinary battery. So you just have a battery and it spins. The ink is made from a chess piece. They’ll take the chess piece, the pawn, and they’ll take the lighter and they’ll light it, and then it’ll start to burn and melt. They’ll put it on a desk. They get a paper bag, and they place it on top. They place it inside the burning piece, and they’ll trap the soot, the smoke. They want that black smoke. It’s carbon . . . Rip open the paper bag. They scrape off the soot. It’s now a powder form. Then they’ll take an antibacterial shampoo or lotion, and they mix it into the carbon powder, and that’s your ink. So they just dip the gun into the ink. And you go ahead and draw your pattern. Genius. Deprivation brings out the creativity in any man. It’s unbelievable, the creativity there. Unbelievable.” —Gil

Batle

Gil Batle, Fiberglass Shank, 2018, ink on paper Courtesy of the artist and the Ricco/Maresca Gallery

“So this guy shows me a shank and it’s made out of this weird-looking waxy material. It’s like if you took old candle wax that’s got that weird beige color to it, and whatever you shape out of it, it looks kind of clumpy. He showed it to me and I said, ‘What the fuck is that?’ He says, ‘It’s fiberglass.’ It’s like the hardest steel, you can’t break that stuff. I said, ‘Where the hell did you get the fiberglass from?’ Filtered cigarettes. You take that filter and you peel off the paper. Take that filter and say you got yourself a little tube of fiberglass, right? Take your lighter and melt it. Let it burn. Then, while it’s melting, you throw it on the ground, on the cement, and take your

foot and give it a good twist. It’s melted fiberglass. I stepped on it and twisted it, and you got yourself a blade right there. This can cut through skin very easily. The inmates back in the day used to save their butts and they would melt them on a plate they heat up coffee with. They’d melt it and shape it into a shank. That’s why they banned filtered cigarettes in prison when I was there in the ’90s. But they allowed the non-filtered cigarettes. So you roll them yourself. Can’t stab anyone with a rolled cigarette. But now I hear they’re completely banned.”

—Gil Batle

48 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

49 Learn how each of the weapons depicted in Gil Batle’s works are constructed in prison environments. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 803-810

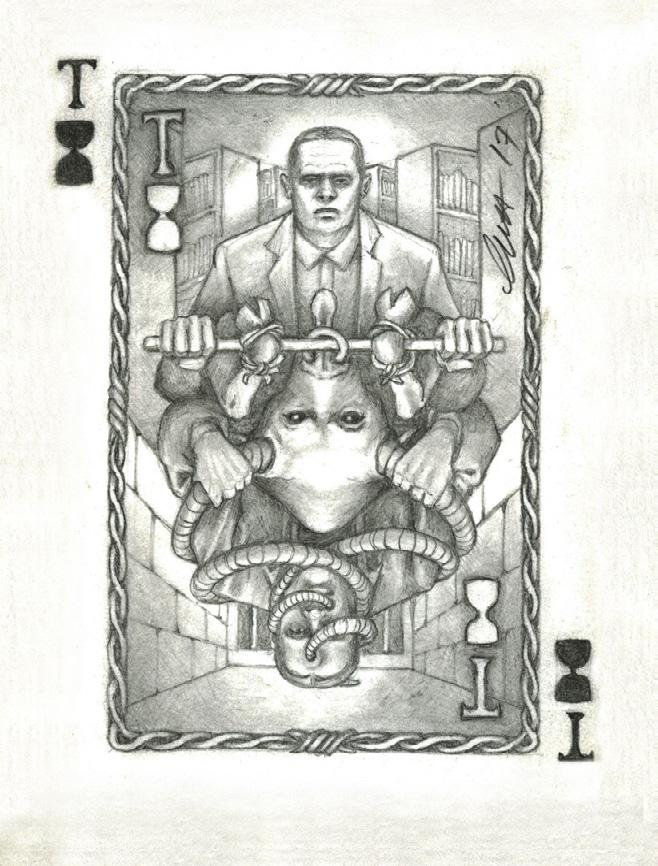

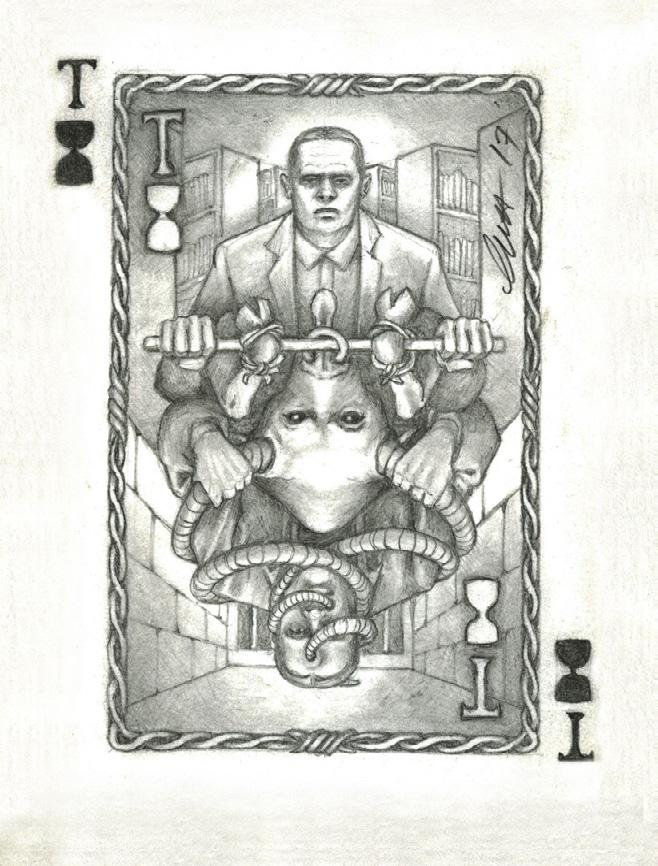

Gil Batle, Kite Deck

this page, from above left

Gil Batle, T Bull, 2017, graphite on cardboard

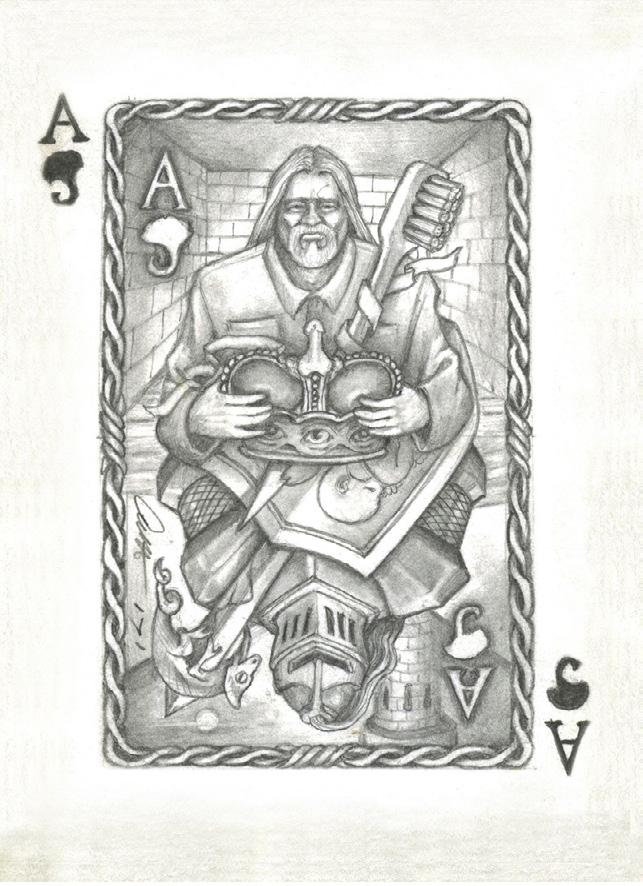

Gil Batle, Ace of Clubs, 2017, graphite on cardboard

Gil Batle, 3 Owl/OG (Old Gangster), 2017, graphite on cardboard

clockwise from top left

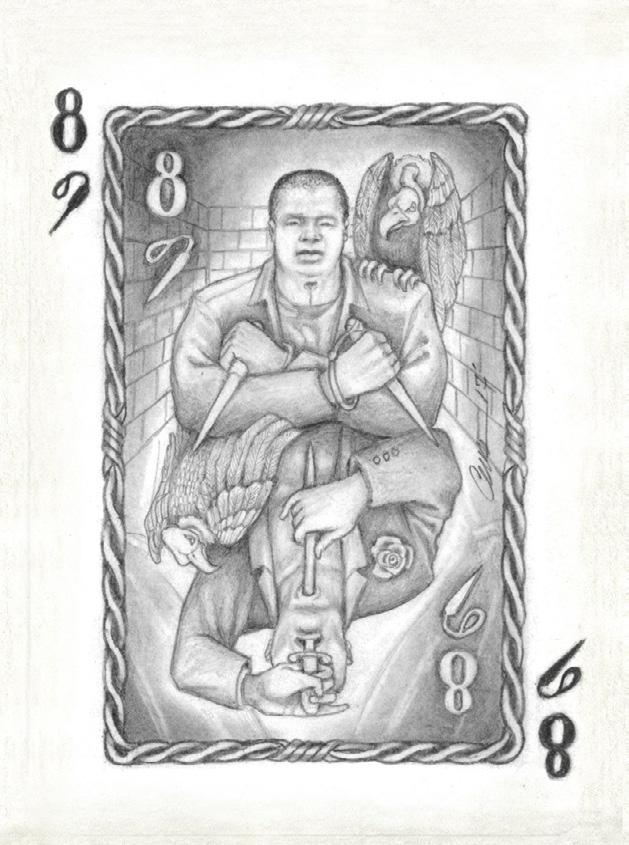

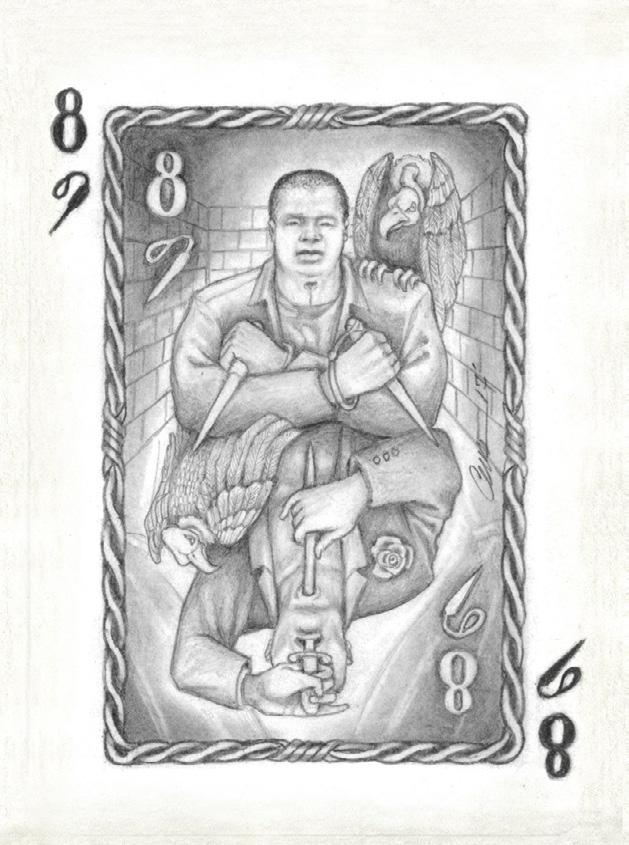

Gil Batle, 8 Sword Swallower, 2017, graphite on cardboard

Gil Batle, V Nazi/Octopus, 2017, graphite on cardboard

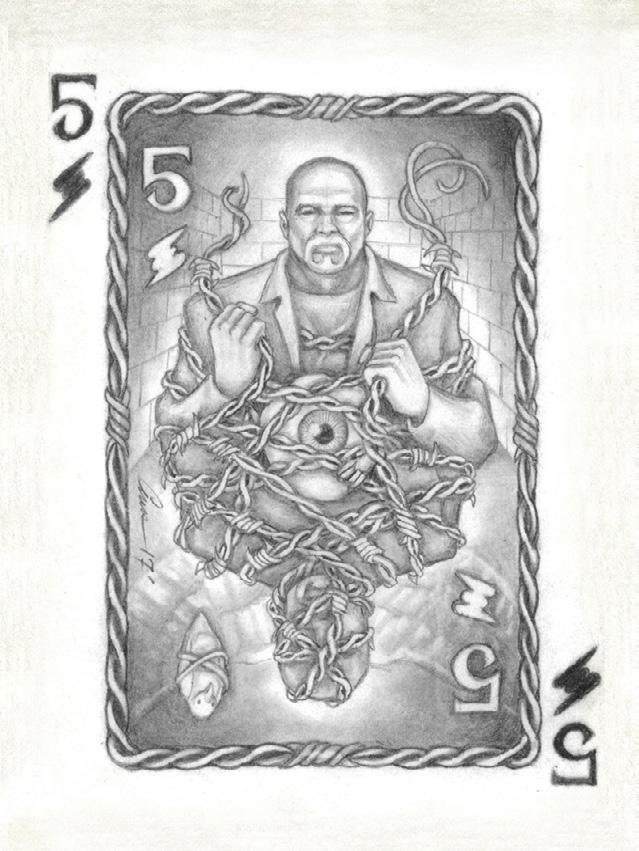

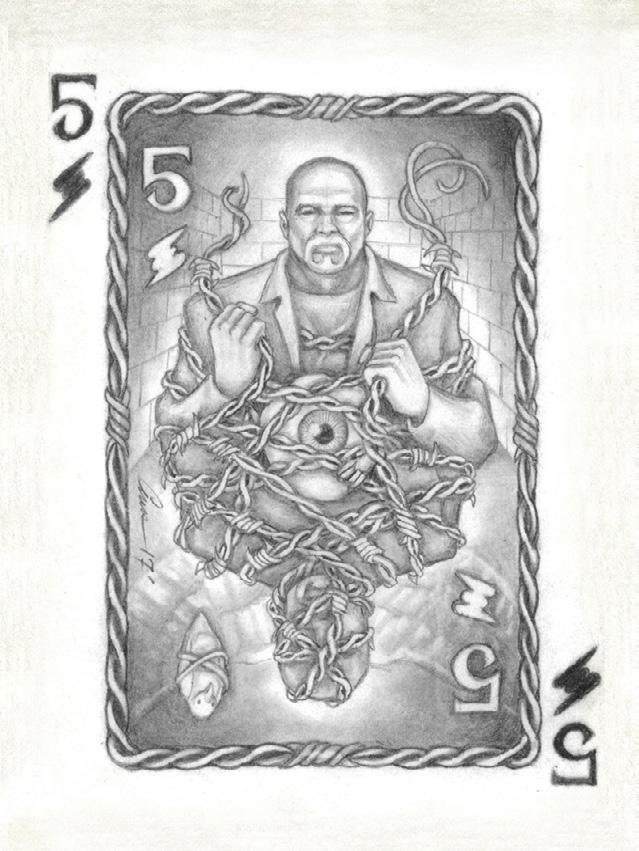

Gil Batle, 5 Eyeball/Barbed Wire, 2017, graphite on cardboard

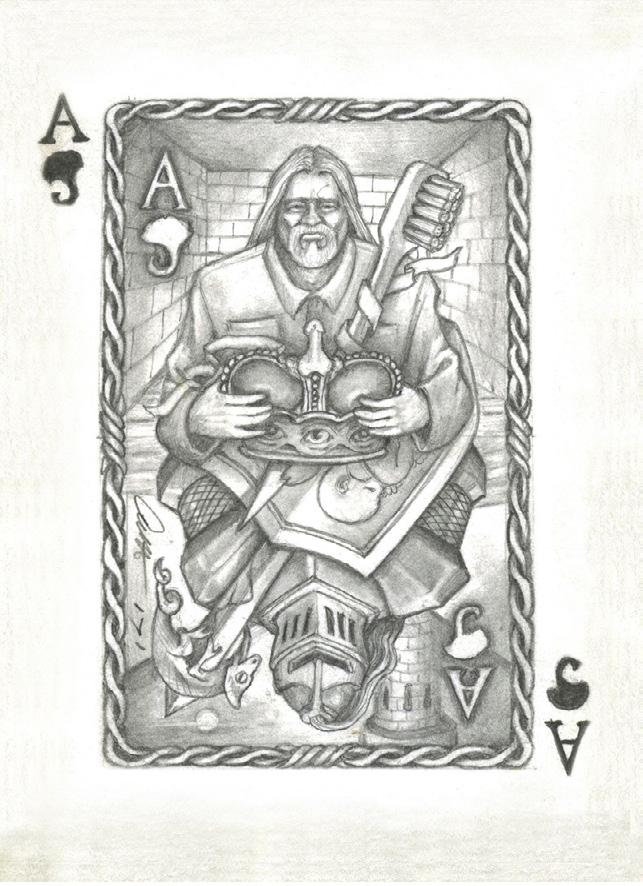

Gil Batle, A Knight, 2017, graphite on cardboard

All courtesy of the artist and Ricco/Maresca Gallery

50 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Bloomberg Lookup Number: 803-809

51

Hear from the artist, Gil Batle, about how prisoners use “kite decks” and playing cards to spread messages during lockdown.

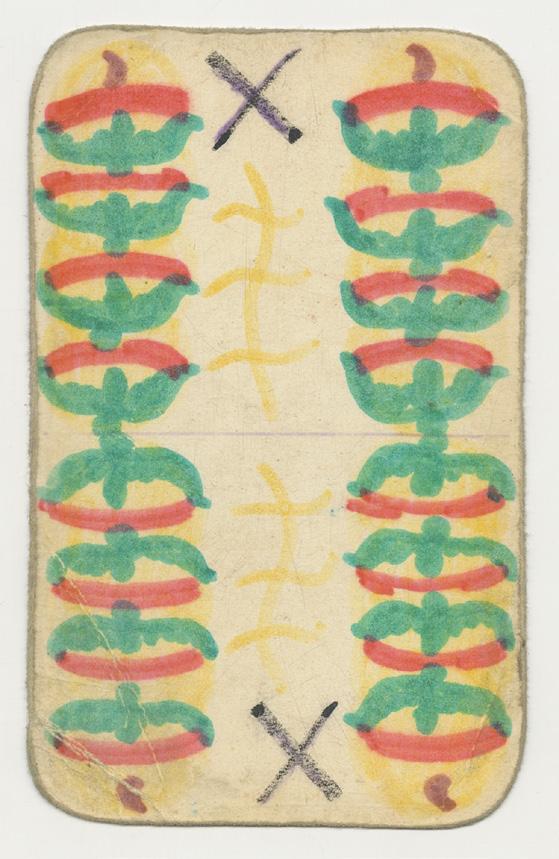

Hungarian Prison Objects

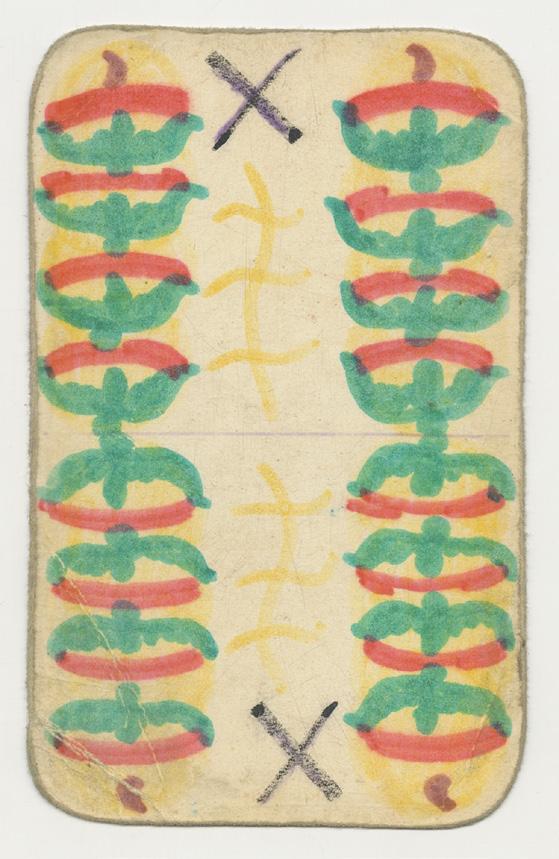

Unknown Maker, Prison Playing Cards, 1980, ink and colored pencil on paper Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

52 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

53

Unknown Maker, Cup-and-Ball Game, 1980, leather, fiber, and wood Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

Unknown Maker, Makeshift Immersion Heater, 1980, metal

Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

Unknown Maker, Makeshift Immersion Heater, 1980, metal

Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

Unknown Maker, Makeshift Immersion Heater, 1980, metal

Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

54

Creating Space in East

West

Visions of Transcendence:

and

Unknown Maker, Cooking Pot, 1980, metal

Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

Unknown Maker, Sieve Used to Make “Prison Narc”, 1980, metal

Courtesy of the Tamás Urbán Collection and Archive of Modern Conflict

55

Tamás Urbán

Tamás Urbán graduated from the Photo Journalism department at the Hungarian Press Association’s Journalism School in Budapest as a student of Éva Keleti and Tamás Féner. In 1976 he was the co-founder of the Studio of Young Photographers (FFS), as well as its first Secretary One year earlier he had exhibited his first series of prison photographs at the Aszód Juvenile Detention Center but was not allowed to show the pictures outside the Center. During the 1980s, he visited several prisons in Hungary, practically living among the inmates in order to get to know them better and gain their trust. From 1990, he worked in Hamburg for Stern magazine and other journals before returning

to Hungary in 1992. His exhibition at the Ernst Museum, Budapest, in 1989, entitled Behind Bars, brought him great success. Urbán received the Béla Balázs Award (1985), WHO Grand Prize (1987), and the Lifetime Award of the Hungarian Association of Photographers. Since 2008, with the support of the National Cultural Fund (NKA) and with a Soros Grant, he has been researching the photographic history of the Hungarian police. His works can be found at the Hungarian Museum of Photography, the Historical Archives of the Hungarian National Museum, as well as at the Körmendi – Csák Photography Collection

Hear more about how Tamás Urbán made a name for himself in the Hungarian art world by photographing correctional facilities, and how the Archive of Modern Conflict became one of the leading private collections related to war and social struggle. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 701

56 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Tamás Urbán, Guard, for Farm Labor Convicts, with His Service Scooter, Állampuszta, 1985, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, Yard Work Break, Youth Reeducation Center, 1970-1990, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

57

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

58

Tamás Urbán, Separation Cell Door as Seen from the Corridor, Tököl, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

59

Tamás Urbán, Two Convicts Hanging Out in One of Ten Cells; the Walls are Decorated with Colorful Photos of Women, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, Convict Performs Reinforcing Exercises Using a Stool, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, Female Convicts Come from Doing Laundry, Pálhalma, 1988, gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, Two Convicts Giving a Christmas Cultural Show, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

60

in

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space

East and West

61

Tamás Urbán, Boy Reading in the Wardrobe, 1970-1990, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, A Young Suicidal Convict with a Maimed Arm and Christmas Mascot, Pálhalma, 1988, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

62

Tamás Urbán, Sweeping the Floor at the Aszód Juvenile Detention Center, 1975, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Tamás Urbán, Ball Factory, Márianosztra, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

63

Tamás Urbán, Iron Workshop Where Huge Iron Structures and High-Voltage Columns Are Being Constructed by Convicted Prisoners; Appropriately, Breakfast Is Served in an Enclosed Iron Cage in the Workshop, Sándorháza, 1985, gelatin silver print Courtesy of the artist and the Archive of Modern Conflict

Obie Weathers

“When I shared this one with my siblings here, some of them said, ‘That’s not how we take bird baths!’ And of course they are right. But I don’t think most of the bathers in art history took baths in the poses they were depicted in. So with this one I’m following along with that tradition. The idealized and posed figure. But, I’m introducing a person of color into a canon of mostly, if not all, white figures. Women, at that. Pure and perfect, not flashing their trauma. And you know, that seems to be a requirement for a Black person to be seen—much in the same way a woman, of any color, needs to be naked to be seen in a museum. Bird baths are simply ways for prisoners to bathe while locked in a cell without access to a shower. A sink, a bit of soap, and maybe a rag is all that’s needed. We here have had to take many of these of late, due to staffing shortages afflicting prisons across the nation. This, at a time when remaining clean is a matter of life and death.

With this painting I could have depicted this figure closer to the reality of what a bird bath looks like for us here, but I question whether it would actually bring anyone closer to this reality. In using an idealized and posed figure, I am keeping the reality the figure represents obscured in the same spirit that prisons work endlessly to keep the reality of the prison within its walls—out of the public’s view. And perhaps the public doesn’t want to see the reality inside

these walls? Or at least not a large enough public to make a significant change in the lives of the millions locked up in the United States. What makes this figure idealized is its externalized trauma. In our struggles for a better life free of unnecessary trauma, Black people have to prove we suffer trauma. We have to have proof of an absent father or an abusive mother. There has to be some sexual abuse and gangs and drugs and alcohol and underfunded schools in our wrecked childhoods. This is how we become worthy. This is our path toward an affirmed humanity, climbing the phrenological ladder. This is not to say that some of us, if not most around me, locked in these cells bird bathing, have not caused serious harm because we have. I know I have. And it’s not excusable, but nor is it intentionally obscuring our humanity.

There’s something else to this painting: It is from the perspective of someone inside the cell, not someone looking in. There is self-reflection happening. And in that self-examination there is something of a cleansing taking place. A healing and a making whole, perhaps, after a reckoning. Also, the figure isn’t focused on the viewer but engrossed within himself. Something deeply spiritual is happening in this dark place. Also something the public isn’t privy to but that takes place more than it is allowed to know. There is a bit of mystery and even hope to this painting.” —Obie Weathers

64 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about his life and the people with him on Death Row. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 725

65

Obie Weathers, Bird Bath, 2021, oil pastel, water-mixable oil, watercolor, crayon, industrial paint, charcoal, graphite, colored pencil, prison floor wax, and collage (paper, birchbark, wasp nest, and Cambodian paper currency) on illustration boards

Courtesy of the artist

“This piece has one foot in the past and one in the future as it comes from my work with a class at UC Santa Barbara. This was my first time working with a class with the tablet I was issued in December. I am trying to juxtapose the low technology of the solitary confinement cell with the high tech of a tablet. The criminal legal system is posing as if it’s making sweeping reforms but it’s all undermined by the continued practice of archaic forms of control like solitary confinement and capital punishment. We have to be very skeptical of these so-called reforms and not rest and think of them as an end.

Then there’s this interaction I’m having with the Literatures in Juvenile Justice class via the tablet. The class is a movement toward a future where justice for youth has truly just outcomes. But I’m having this interaction while I’m under a

sentence of death that has been justified in part by my experiences as a youth and my encounters with the criminal legal system during those tender years.

The title comes from Ryan Flaco Rising, who created the Underground Scholars support program at the University of California for system-impacted people to help them with their education goals. Being sentenced to death and held in solitary for two decades is a type of underground existence. And scholarship is one thing I’ve been up to down here and hope to continue to find the support needed to move forward. Imagine if all the money the state was paying to hold me in this cell and potentially execute me went instead toward educating me when we know that education reduces recidivism rates.” —Obie Weathers

Lookup Number: 722

66 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about teaching UC Santa Barbara students while in solitary confinement. Bloomberg

67

Obie Weathers, Underground Scholar, 2023, oil, acrylic, colored pencil, graphite, and collage on illustration board

Courtesy of the artist

“This painting begins with a postcard I received featuring a picture of a wood sculpture of Guanyin of the Southern Sea — the Bodhisattva. This sculpture is dated somewhere around the eleventh or twelfth century. The Bodhisattva’s pose, exuding ease, served as the general reference for the pose we find another Black Human subject captured in, within another barren cell. This million-dollar barren cell is just as much the subject of this painting as the colorful, life-filled human we see in the pose of one known as a compassionate helper of others. And yet, the endless millions spent on endless cells like quicksand pits mire millions of bodies with the potential to heal while the cells go on selling us only the illusion of security. If prison cells were the hulls of ships, they would sail us nowhere. A sad fact is that if the United States hasn’t been able to incarcerate crime out of existence, we won’t ever be able to. When I was arrested, the 15th of February in the year 2000, the two millionth person had also entered the carceral system of America. At the time I was but eighteen and couldn’t then imagine the potential within me to write, think, paint — to be loved and to give love. That took time — decades — and much support from others. We might call them Credible Messengers, men who looked like me, talked like me, and shared much in common with me in our backgrounds. Only they had metabolized much of that shared or similar experience and patched up their wounded humanity. And because they had

accomplished this difficult work, they could now pass down to me the blessing of their wisdom-medicine. It wasn’t until I met my friend Ryan Flaco Rising that I learned this language of the Credible Messenger. I’d seen it over the course of my experiences and exchanges with others on death row. I’d seen it in my fellow prisoner Christopher Young when he talked about mentoring youth, when he said in so many words that in order to help others heal, one needs the insight of empathy to help the healer guide their medicine to the precise mark within the other’s heart. Support groups are so powerful because people of similar experience are intimate with the contours of certain catastrophes and can walk another out the craters to a better place. And yet, for some strange reason we don’t widely recognize that people snared in cycles of criminalized behavior can also benefit from the support of those who have clawed their way out of those very same cycles. Not only do we not widely recognize this but we execute the very people — such as Chris Young — who could have provided many practical maps out of these sad cycles for so many. This painting pleas for those who remain: May we invest in the technology of mentorship. May we invest in the humans who can and who want to help heal but who are held in many millions of cells, unable to invest their human capital into those who would make all our lives richer.” —Obie Weathers

68 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about how he uses his story to guide young people out of dark places. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 723

69

Obie Weathers, Credible Messenger, 2022, water-mixable oil, oil pastel, watercolor charcoal, graphite, colored pencil, watercolor, charcoal, and collage (paper, US and Cambodian stamps, a leaf, and foil) on boards

Courtesy of the artist

“The title of this one comes from an Audre Lorde quote: ‘Black feminism is not white feminism in blackface.’ I began this one with the idea of expanding what our deities look like. As a practicing Buddhist, albeit in my chaotic fashion, I started this conversation by envisioning the Tibetan Buddhist Goddess, the White Tara, as trans. Maybe I was thinking of Tenzin Mariko? But for certain all the transwomen of color are being murdered in the states, so I went further and considered this ‘white’ Tara as Black. Racially Black, that is, as the White Tara isn’t racially white at all. So I’m messing with our notions around color. But mainly I wanted to consider transwomen of color as holy by using a revered and sacred form.

I’m also thinking of ableism and notions of beauty by depicting her with one arm. I met someone with one arm last year and she absolutely schooled me on how small my thinking still is around beauty. And she did so simply by being visible in my life for a brief period of time. So I’m pushing us on the question of who has the right to be visible and held in a dignified light in our collective presence. Not pressed into huddles in the shadows on the margins of our world.

The Audre Lorde quote makes me think about intersectionality. How diverse groups of people have varying needs based on their historical points of reference. Or are suffering and having their ability to live full lives limited because of social forces that isolate and target them. This is something I can relate to as a Black man sentenced to death in the South.

I’m not trans, nor am I comparing my violent and morally reprehensible acts (that led to my being sentenced to death) twenty-one years ago to being trans. But at forty years old and having done considerable work on myself over the last twenty-one years of incarceration, I can see clearly that the idea that I need to be locked up, or held in solitary, or let alone executed, is one that comes from a culture where the gods don’t look like me. My visage is reviled. My humanity is marketed as less-than. Check the historical records.

I empathize with people who aren’t able to see me as worthy of an opportunity for a fuller life than this solitary cage allows — as I can understand a person’s fear of a trans person of any color or gender. We’ve all been mocked, forced into the shadows or cells and denied a chance to be heard. Or silenced before we developed a voice, like I was when I was sentenced to death as a mentally ill and confused kid. But we are going to have to start thinking about our knee-jerk reactions to people because people are dying when they don’t need to. People are being denied opportunities to flourish in life because of misunderstood processes of being human. For me this plays out in how I’m seen as not being able to learn and grow from my mistakes. Simply by virtue of my being sentenced to death at nineteen this is suggested. It’s a misunderstanding of the process of becoming more humane: in seeing and deep reflection.”

—Obie Weathers

70 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about queer identity in the hyper-masculine prison environment. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 724

71

Obie Weathers, Black Tranz Tara Is Not White Tara in Black Face, 2021, water-mixable oil, oil pastel, watercolor, colored pencil, charcoal, crayon, and collage (paper, paper tape, batik, and faux gem) on board

Courtesy of the artist

“The artwork that I share with you is titled Execution Date. What I was doing with this painting was just simply trying to say how an execution date for me is unnecessary, because it’s overboard, it’s like saying that me being held in solitary confinement is not enough, right?

The mushrooms that are in the begging bowl he’s holding, that comes from these ideas that I got from Adrienne Maree Brown; she talks about how you might see one mushroom, but underground there is a vast network that

connects with other mushrooms, right? And I think about those mushrooms in terms of community and connection, even though I’m in this cell, alone. I know that I’m connected with other people. And I know that if I have any chance of life, of surviving, it’s going to be from the help that I get from the community. And I know that my being alive today has only come from my connections with others.”

—Obie Weathers

72 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Obie Weathers, Execution Date, 2022, water-mixable oil, oil pastel, watercolor charcoal, crayon, graphite, colored pencil, and collage (paper and birch bark) on boards Courtesy of the artist

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about the inspiration and references within his work Execution Date. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 721

Courtesy of the artist and Ai Weiwei Studio

Ai Weiwei discusses the spiritual and aesthetic strengths of Obie Weathers’ and Howard Guidry’s work ahead of their inclusion in a group exhibition with other incarcerated artists. Thereafter, Obie talks about what it means to

have his art be seen and appreciated while he remains in solitary confinement, and how important it is that he gets to be perceived as the man he has become rather than the man he was at his arrest.

73

Obie Weathers and Ai Weiwei, Ai Weiwei and Obie Message – Buddhas on Death Row, 2022, digital film, 7:22 minutes

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about his art and loneliness. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 719

Christopher Young, Obie Weathers, and Howard Guidry, JASIRI, a feature documentary of death row, 2023, digital film and documentary sample, 10:57 minutes Courtesy of the artists and Reaching Out Productions

Christopher Young, Obie Weathers, and Howard Guidry have served a combined fifty-three years of solitary confinement in the Polunsky Unit Prison in Texas— ground zero for death row in America. In this self-portrait, the three men reflect on the value of human life as they await their execution date. Without access to educational programs, contact visits, cameras, television, or phone calls, the men devised a clandestine way to make this film. Through a network of independent cameramen, activists, and filmmakers on the outside, Young, Weather, and Guidry were able to bring their messages out of prison and to the screen.

JASIRI is directed from death row at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit, a maximum-security prison in Livingston, Texas. It is widely considered to be one of the top-ten worst prisons in the United States, notorious for keeping men on death row in solitary confinement for twenty-three hours a day without access to contact visits, phones, or television. Many men serving a death sentence here have suffered psychotic breaks, attempted, or successfully committed suicide waiting out their appeals process and sentence. In Texas, convicted people spend an average of sixteen years on death row.

The story begins with director Christopher Young, a man in his early thirties from San

Antonio, Texas, who spent thirteen years on death row. Christopher’s story is one of spiritual growth and redemption in the face of systemic oppression. On death row, Christopher joins non-violent protests to bring attention to the inhumane conditions at Polunsky Unit; he learns to cultivate his voice through writing, a tool to reach the outside world; he teaches himself to paint, art therapy to express himself; and he learns the meaning of fatherhood despite his physical distance. Christopher matures, he becomes a leader, and takes on the Swahili name JASIRI, meaning “brave.”

Before Christopher’s life ended, he wrote extensively about this film, and created both a script and blueprint to follow so that his vision could be faithfully accomplished. In this blueprint, Christopher asked his friend and fellow death row inmate Obie Weathers to continue the project.

This film is a bold expression of humanity in the face of ruthless oppression. Every word, every question, every shot, every image comes directly from Christopher, Obie, and Howard as their final testament in the face of a death sentence. JASIRI shows the world that this struggle is bigger than one individual’s story; this is a story of what justice looks like in America, and ultimately a story of the country itself.

74 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Courtesy of the artist and Reaching Out Productions

Credible Messenger is a brief documentary centered on the art and teachings of Obie Weathers, a death row inmate who has been subjected to solitary confinement since the early 2000s. While serving his sentence, Obie began creating art and writing about the carceral system, personal growth, and what he would have needed as a teen to avoid serving

time, eventually partnering with an organization that brings his work to a broader audience. This video interviews both Obie and many of the youths and adults he has positively influenced through his written correspondence and art, emphasizing the power of human connection and the limits of a punitive justice system.

75

Obie Weathers, Credible Messenger, 2023, digital film, 15:10 minutes

Hear from the artist, Obie Weathers, about how he and Christopher Young utilized film as resistance art and a vessel for transformation. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 720

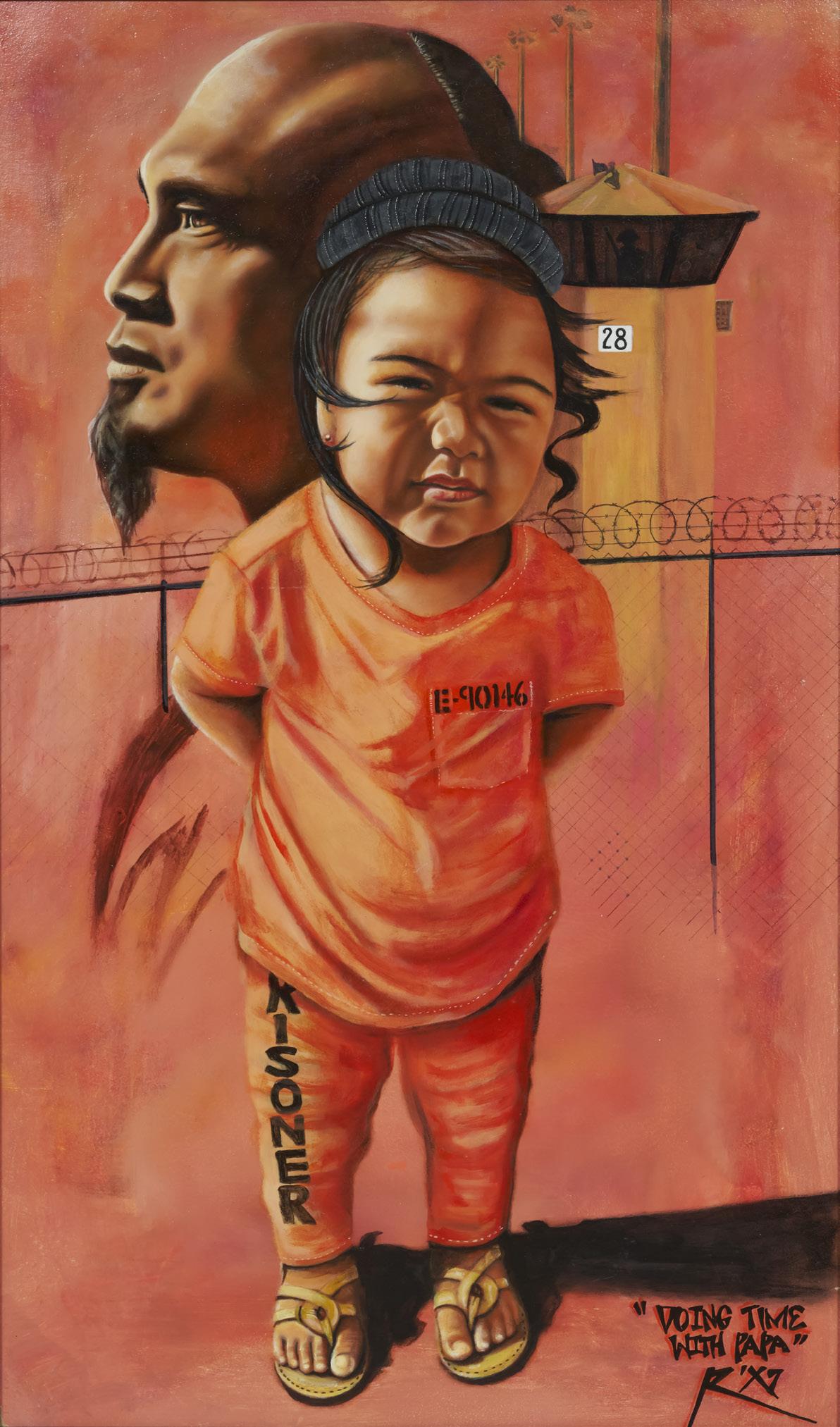

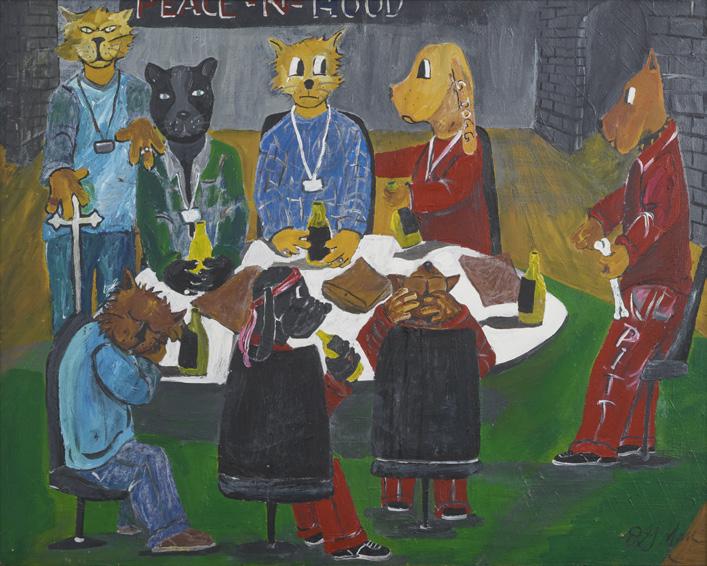

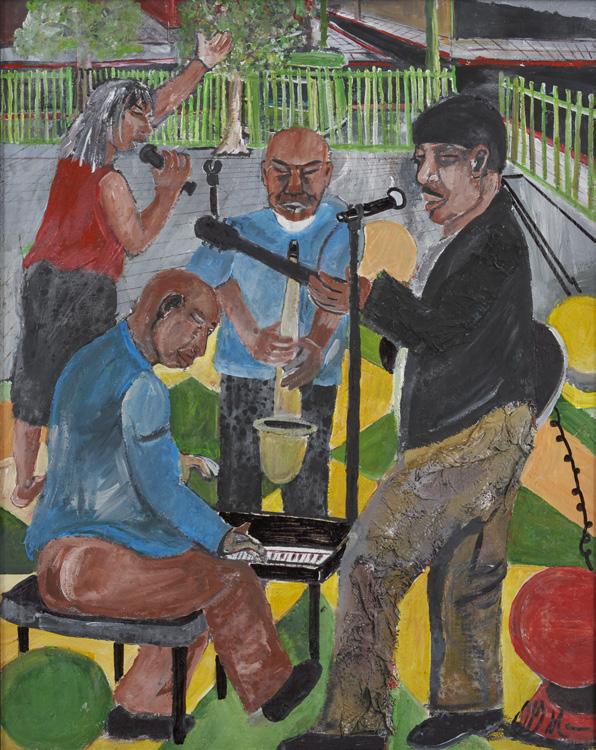

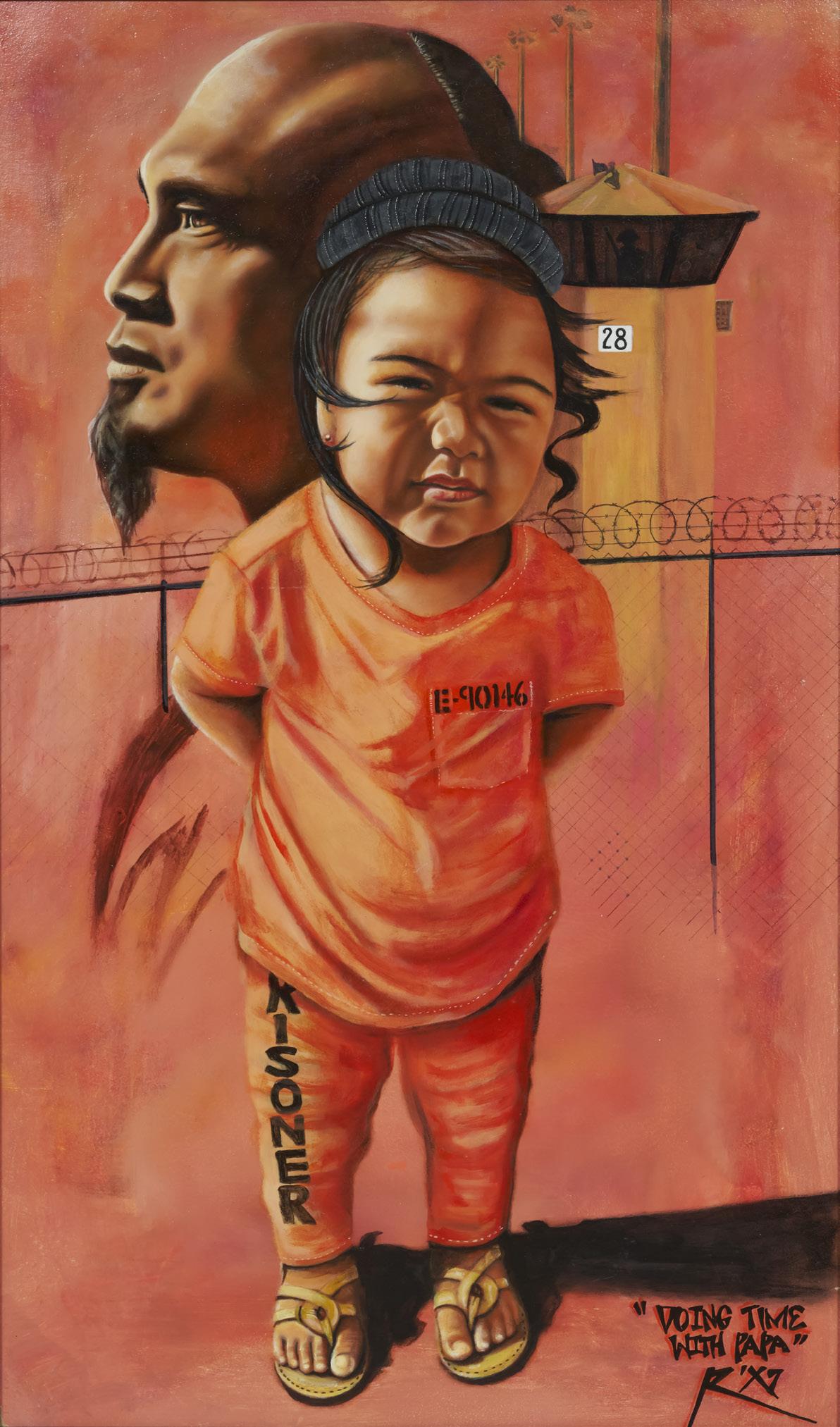

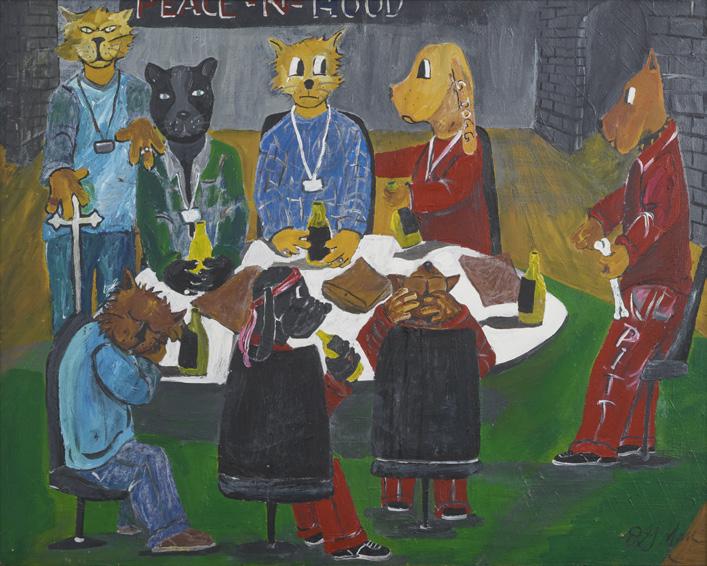

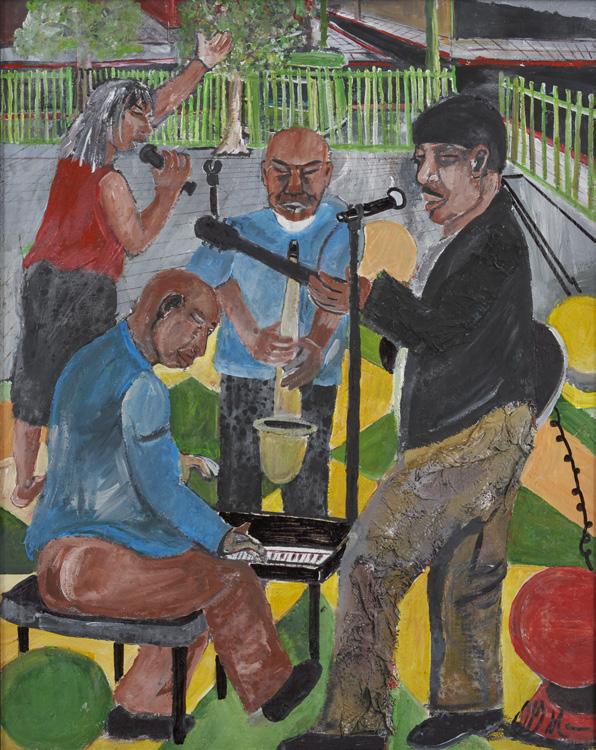

Huma House

“Huma House, a 501(c)(3)organization located in Los Angeles, California, was established with the knowledge that art exhibitions can serve as a potent activist tool. Their core mission revolves around the belief that art can be a transformative force, providing alternative healing methods that guide nations towards peace and enable youth to tap into their full potential. Initially gaining prominence for their powerful and thought-provoking art exhibitions, Huma House was bolstered by profound community support. These exhibitions not only showcased the talent of artists but also illuminated the pressing issues faced by grassroots movements. With

the sustained support from the community, these exhibitions expanded, and Huma House began spotlighting artists from these movements on an international stage. In addition to their art exhibitions, Huma House runs an art education program in South Central Los Angeles. This program provides local teens with tools and opportunities to express themselves through art.

Co-founded by Meetra Johansen and Tobias Tubbs, Huma House continues its commitment to the community and the transformative power of art in South Central Los Angeles.”

—Meetra Johansen

“Reading through history, some visionary minds seem to have traveled from far in the future to share their discoveries with people of that era. They leave a meaningful, lasting impression long after they’ve moved on from this world, a testament to their genius and renown. Omar Khayyam must be one such time traveler who graced the eleventh century with his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, and poetry. An intellectual giant, Khayyam dared to write the Rubaiyat, full of daring and subversive secular themes encouraging people to spend the short time they had being happy, drinking wine, and enjoying this life instead of fixating on the afterlife. These themes adorn the frame of my painting, a seven-foot rendition of the miniature I originally created of Khayyam and his Rubaiyat. Festive colors depict the flowing wine and joyous spirits that frequent Khayyam’s poetry, an ode to an intellectual giant.” —Omid Mokri

76 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Hear from the artist, Omid Mokri, share insight into his displayed artworks. Bloomberg Lookup Number: 757-759

Omid Mokri

“There were prison guards that hated me and there were prison guards that loved me. There was one in particular that would come and destroy my cell completely on a regular basis. That’s heartbreaking. I had moments where a cop would put me in isolation, like in a cement closet room, and ransack my cell and steal my paintings. And then other inmates would tell me, ‘Oh yeah, he just took it to his car.’ I was painting at night when everybody was sleeping. I would make this camouflage curtain over the wall that was the color of the wall, and I would drape it over my painting when I couldn’t finish it. Because sometimes I couldn’t finish it overnight and I had to hide it so when the cops would do the count and look through the little window,

they would not notice my bright color drawing or painting on the wall. I would fold the paintings and put them in small manila envelopes with directions to my family how to fix them at home. That’s how I was able to get these artworks out. While I was incarcerated, I was having group shows, which was pretty cool. That was actually a way for me to get my artwork out without it being stolen. Art can be a turning point, like, it can change things like it did for me at the darkest hour of my life. Art is like a light. I wanna say that art is my home. There’s no door, no barrier. It doesn’t have borders, no walls, no bars. This is my habitat where I live. And this haven has kept me alive.” —Omid Mokri

77

Omid Mokri, Come Fill the Cup (Omar Khayyam), 2005, acrylic and gold on linen Courtesy of the artist and Huma House

“King Midas is my portrayal of my cellmate, not as he appeared to those who made him feel rejected and lost, a casualty of the prison system, but instead as a king, with power and majesty, basking in the light of his full potential. A man with dreams, not just another inmate number. Dignified, not discarded. I made this painting on a canvas of discarded bed sheets, treated with tea. I painstakingly ground up colored pencils into a paste with which I painted, using paintbrushes fashioned out of hair cuttings affixed to plastic spoons.” —Omid Mokri

78 Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space in East and West

Omid Mokri, King Midas, 2011, colored pencil, crushed colored pencil paint on prison bed sheet, tea Courtesy of the artist and Huma House

“Women, Life, Freedom! The Empress’s heavy crown symbolizes hope, light, and emancipation. Specially designed for the only Shahbanu of Iran, the crown was modeled after those of the old Sasanian Kings, using pearls, diamonds, emeralds, spinels, and rubies from the Iranian Imperial Treasury. The sunburst motif is front and center, emulating the glory and power of the Persian Empire and referencing the rich history of its people. This crown represents the optimism and boundless possibilities offered by the youth of Iran, and generations yet to come.”

—Omid Mokri

79

Omid Mokri, Our Crown!, 2023, acrylic on handmade red linen fabric

Courtesy of the artist and Huma House

Kenneth Webb

“Unbending is an insight into a collection of memories. Ideas about tribal violence, community mourning, and public grief are central in this captured notion. I remembered the memorials I’ve witnessed in my lifetime and focused on the core of what I felt, what each experience meant to me.” —Kenneth Webb

Kenneth Webb, Unbending, Chino Men’s Institution, 2023, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Huma House

80

in

Visions of Transcendence: Creating Space

East and West

“Small Garden, Strange Soil is a recognition of the notion of the unlikely. The oddity that finds normality in its own container. Los Angeles street culture is a strange realm, the laws of life differ from the rest of society. Yet through its odd nature arises an ecosystem. A place primed with beauty and decay interwoven.”

—Kenneth Webb

81

Kenneth Webb, Small Garden, Strange Soil, Chino Men’s Institution, 2022, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Huma House

Dean Gillispie