‘

‘

ALWAYS PRESENTS ITSELF AS SERVING THE

BUT ITS REAL AMBITION IS TO REDESIGN THE HUMAN.

THE HISTORY OF DESIGN IS THEREFORE A HISTORY OF EVOLVING CONCEPTIONS OF THE HUMAN.

TO TALK ABOUT DESIGN IS TO TALK ABOUT THE STATE OF OUR SPECIES.’

- BEATRIZE COLOMINA & MARK WIGLEY,

Summary.........................................

A Dynamic Interplay and Danger of Self-Destruction.............

Genesis of Parametric Design........

Undermined Human Creativity........

Loss of Ethical Values.....................

Conclusion......................................

Bibliography....................................

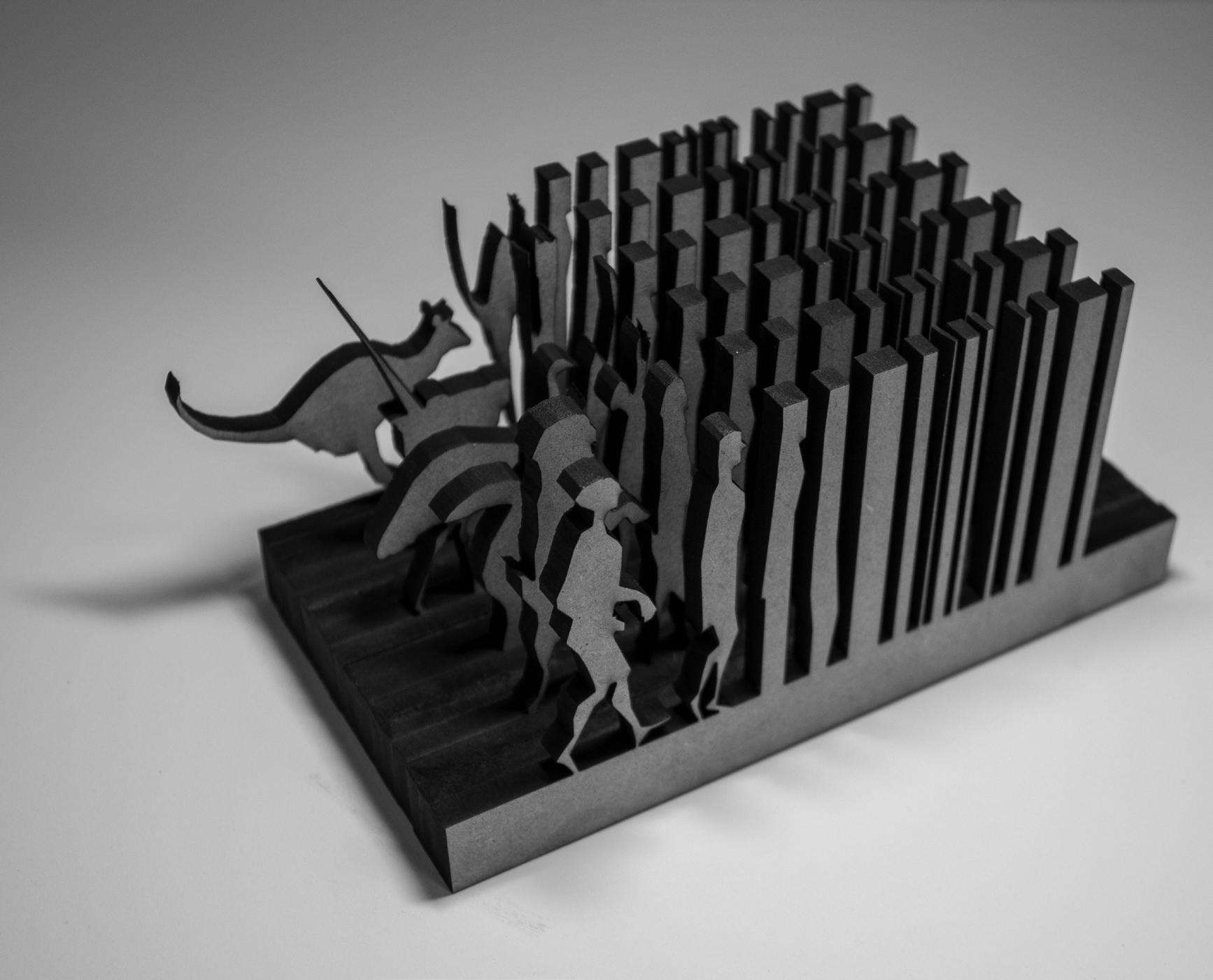

Figure 1 (Cover Image): Humans invented machines, and there is a dynamic interplay between the creator and creation. (Gart, 2022)

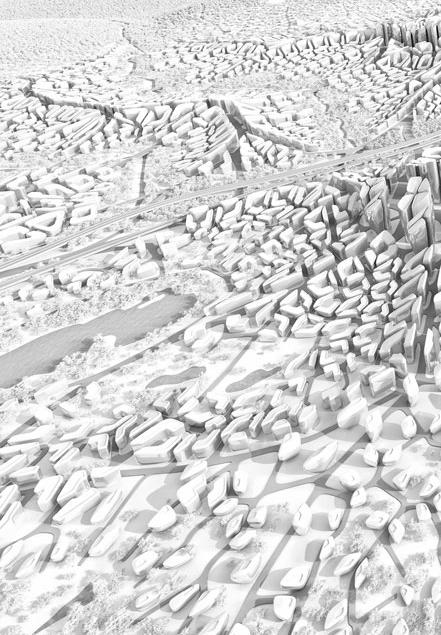

Figure 2 (Left Image): Technological and parametric decision-making defines humans’ way of living. (Mario Cucinella Architects, 2022)

Humanism versus technology is an expanding field of research wherein modes of design decision-making have rapidly evolved in recent decades. New parametric modelling tools have changed the traditional relationship between the designer and their designed objects. We argue that the new design parameters, based on sophisticated algorithms and rules, are undermining human creativity by handing the process of decision-making over to the machine. We also argue that the machine has no inherent ethical values and aims for efficiency and perfection. This leads, as our conclusion shows, to diminishing the moral value of designing as a uniquely human pursuit.

(Summary Word Count: 98 words)

(Article Word Count: 2582 words)

Mechanical decision-making risks reducing reality to mere binary code, and eventually into leading humanity into nothingness.

(Zhang, 2023)

The mutual invention between humans and the artificial world, in which they inhabit, plays a pivotal role in human evolution.1 This ongoing interchange consistently challenges conventional notions of power and utility, reshaping the essence of humanity. The central question in this discourse is: who envisions the course of human evolution, and what destination awaits us?

Humanism versus technology is an expanding field of research where researchers debate the dynamic interplay between humans and technology. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, in their work “Are We Human?”, analyze the mutual invention of humans and artifacts, raising critical questions about whether technology enhances humanity.2 I agree with this stance, in that technologies can empower humans as physical and mental extensions, regardless of the ethics of the utility, but they also continually reinvent the human species by influencing how we view ourselves and our potential in those artifacts.3 Tools not only challenge existing concepts of utility but also redefine hu-

mans, placing humans in a perpetual state of being both the cause and the effect.4 Thus, increased mechanical decision-making in design risks diminishing the moral values of the process and potentially leading humanity to self-destruction, reducing existence to mere binary code, and eventually into nothingness.5

Notes:

1 Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers), 78.

2 Colomina, 2016, 78.

3 Colomina, 2016, 54.

4 Colomina, 2016, 56-57.

5 Ellen Meiresonne, Donna Jeanne Haraway, Rusten Hogness, Atelier Graphoui, and Icarus Films, 2017, Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival (Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films).

Figure 3In recent decades, due to sociological demands and the development of computational technology, design or decision-making entities have evolved from humans to machines.6 Mid-20th century aesthetic fatigue from industrial mass production led to a preference for differentiation over standardization.7 Taking full advantage of the computational revolution, parametric design emerged as a response to the sociological problems of ‘mass society’ and the ‘standardized consumption of modernization’, enabling continuous differentiation, versioning, iteration, mass customization, and bespoke designing.8

Since the late 20th century, digital parametric design, as a unique mechanical decision-making endeavour, quickly crystallized, becoming the driving force of the architectural design profession and fundamentally altering the traditional relationship between designers and their designed objects.9 Buildings, once viewed as materialized drawings, are now seen as materialized digital information.10 In the parametric era, Building Information Modelling (BIM) integrates site,

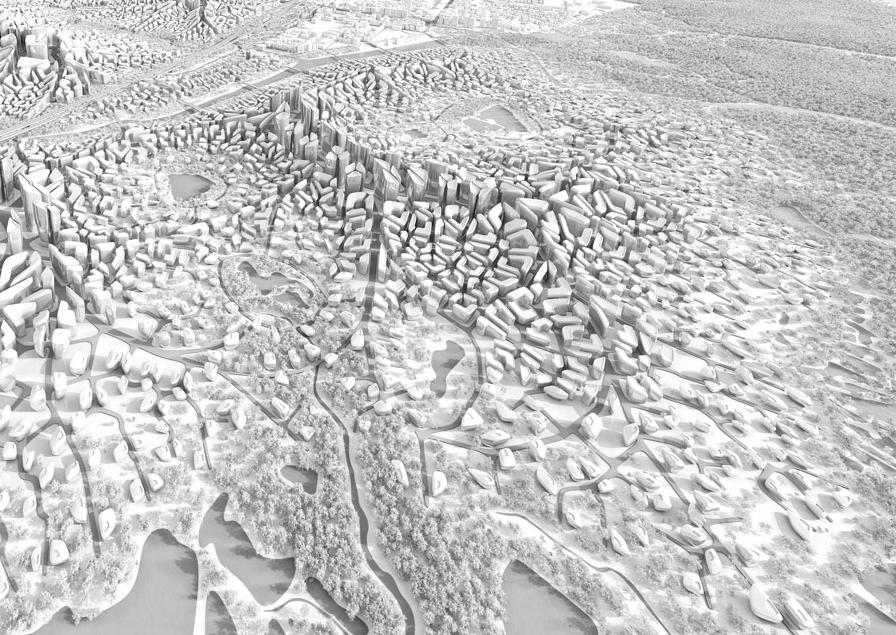

Parametric desiging enables continuous differentiation, versioning, iteration and mass customization. (Frick, 2022)

Figure 4

Figure 4

PARAMETRIC DESIGN MERGED IN RESPONSE TO THE NEED OF

program, and expressive intention into building forms as parameters.11 This framework allows for the easy evaluation of financial, environmental, and social aspects, transforming buildings into solutions for sociological problems.12 Furthermore, machines surpass the human brain in calculation speed and data storage capacity.13 Defining dramatic parametric shapes relies on complex mathematical calculations only machines can perform.14 Multi-dimensional transformations, such as scaling, translation, and shearing, can be achieved within seconds by machines, whereas they might take humans days or years.15 Software packages incorporate symmetry, logical data structures and visual scripting, enhancing architectural capabilities beyond what can be achieved manually.16 Employing machines with these superiority minimizes human labour costs.17

There is a fundamental difference between machine and human decision-making in architectural decision-making. Traditional concept formation operates within the mind of the architect through visual reasoning

about space, structure, and form.18 In contrast, parametric machine decision-making relies on sophisticated algorithms, with architectural concepts expressed through generative rules encoded in a genetic language.19 Handing the decision-making process over to machines forces humans into a new avenue for design thinking, emphasizing inner logic over external forms.2021 Designers now juggle multiple forms of data and images in digital environments, a system Rivka Oxman identifies as digital design thinking.22 This non-typological, non-deterministic approach prefers discrete and differentiated over generic and typological, focusing on the relationships among the designer, information, and images.23 Creativity lies in logical ‘grammar’ rather than in form vocabulary.24 With the rise of informational design frameworks and computational power, technology and design thinking are increasingly intertwined.25 As machines take over, human designers risk becoming disposable, and relegated to inputting data parameters while the machine becomes the central organism driving the design process.26

6 Patrick Schumacher, 2016, Parametricism 2.0: Rethinking Architecture’s Agenda for the 21st Century, 1st ed. (John Wiley & Sons), 1-12.

7 Schumacher, 2016, 10.

8 Schumacher, 2016, 10.

9 Rivka Oxman, 2006, ‘Theory and Design in the First Digital Age’, Design Studies 27, no. 3, 262.

10 Oxman, 2006, 229.

11 William Mitchell, 2005, ‘Constructing Complexity’, in Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Futures, Vienna, Austria, 1.

12 James Andrachuk, Christos C. Bolos, Avi Forman, and Marcus A. Hooks, 2014, ‘The Price of a Paradigm by David Ross Scheer’, in Perspecta 47 (MIT Press, United States), 197.

13 Mark Fischetti, 2011, ‘Computers versus Brains’, Scientific American Magazine 305, no. 5 (November).

14 Oxman, 2006, 229.

15 John Fraser, 1995, An Evolutionary Architecture (Architectural Association), 29.

16 Fraser, 1995, 26-33.

17 Mitchell, 2005, 1.

18 Fraser, 1995, 9.

19 Fraser, 1995, 9.

20 Oxman, 2006, 262.

21 Fraser, 1995, 10.

22 Oxman, 2006, 261.

23 Oxman, 2006, 262.

24 Oxman, 2006, 262.

25 Phillip Bernstein, 2018, Architecture Design Data: Practice Competency in the Era of Computation (Walter de Gruyter GmbH), 8.

26 Colomina, 2016, 76.

Colomina and Wigley posit that good design invents good humans.27 Yet, does parametric design technology, lauded as the pinnacle of contemporary architectural design, elevate human creativity? This essay contends that handing decision-making tasks to machines will undermine human creativity.28 It may create a false sense of reality and design optimization, elevate mechanical computation to unwarranted importance, and constrain the design process to fit program limitations.29

First, machine decision-making creates a false sense of reality and design optimization. The parametric interface provides a phenomenological model, which is tentative, adaptable, and constantly changing, but never achieves absolute isomorphism with reality.30 For example, in the digital parametric space, all information can be compressed to simple numbers ‘0’ and ‘1’; computation can be reduced to simple logical statements such as ‘and’ or ‘nor’.31 No matter how complex the digital organism may become, the nature of parameters limits the digital tools to simplification,

assumption, and manipulation.32 As David Bohm stated, real things distinguish themselves from our imagination by remaining independent of our thoughts.33 There is a complexity gap between the real-world system and the simulation of human artifacts; there are always more parameters than humanly defined.34 Informed by calculation, mapping, and resolution of differences, the digital creative decision-making process fundamentally is based on a relational dialogue between the real world and the parametric abstraction.35 The design informed by this virtual simulation directly contradicts the sensitivity and intuition of the physical and sociological world.36

Second, parametric tools often elevate computer outputs to unwarranted importance, enforcing an unnecessary glorification of computational complexity.37 For example, our new digital capacity has enabled the construction of irregular shapes; however, many of these buildings are deployed merely for their sensational effect.38 These designs are criticized for their short-lived seduction of the surpris-

ing and the compromise of Procrustean simplification.39 In academia, students are encouraged to create meaningless and exaggerated shapes without truthful reflection of architectural function; they are rewarded for the over-glorification of computational complexity.40 Another issue is over-concentration; the goals of certain software products appear egocentric and ignore the practicality of the creative process.41 For instance, BIM aims to include cost, energy, and material calculations in a single model. However, specific modelling tasks, like energy modelling, require distinct software, codes, and file formats, with fundamentally different methodologies.42 Consequently, architects must manage multiple models concurrently for a single project, posing integration and coordination challenges.43 Instead of freeing and simplifying representation, this egocentric ideology rigidifies and complicates it, as Kostas Terzidis criticized, ‘merely to participate in the digital fashion.’44

Finally, parametric mechanical interfaces often constrain the design process to fit within program limitations.

Albert Einstein once said, ‘Creativity is seeing what others see and thinking what no one else ever thought’. It is ironic that parametric tools, like Revit, aim to nullify and fix the representation or abstraction methods of architectural elements.45 These algorithms, originally envisioned as pioneers’ thoughts, are precisely the enemy of true, living and present creativity. In the parametric interface, instead of expressing geometrical qualities from the unique perspectives of a particular project, universal parametric blocks and families rigidify design outcomes.46 If we view parametric design as a language of architectural thinking, where parameters are grammar and families are vocabulary, the “parametric language” appears simple but constrained by morphological regularity, grammar, and special syntax.4748 These constraints limit creative freedom significantly. Instead of creating new doors, windows, beams, and columns, architects now download and import existing universal families from the Autodesk website.49 Furthermore, this newly widespread universal language endangers local

design languages and global design linguistic diversity. Contractors and clients expect ‘automatically coordinated construction documents’, ‘accurate cost and scheduling estimates’, ‘automated program verification’, and ‘the digital transfer of design’.50 Architects are forced to choose from given architectural components rather than free creative expression.51

27 Colomina, 2016, 78.

28 Fraser, 1995, 18.

29 Fraser, 1995, 18.

30 Fraser, 1995, 117.

31 Fraser, 1995, 23.

32 Fraser, 1995, 26.

33 Fraser, 1995, 117.

34 Fraser, 1995, 117.

35 Fraser, 1995, 117.

36 Fraser, 1995, 117.

37 Fraser, 1995, 23.

38 Mitchell, 2005, 10.

39 Mitchell, 2005, 10.

40 University of Adelaide, 2021, School of Architecture and Built Environment Catalogue, Access at: https://issuu.com/ ecms.uofa/docs/diptych_sabe_uofa_catalogue_2021.

41 Moe, Kiel, 2007, ‘The non-standard, un-automatic prehistory of standardization and automation in architecture’,

In 95th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, Fresh Air, ACSA Annual Meeting, 435.

42 Moe, 2007, 435.

43 Moe, 2007, 435.

44 Kostas Terzidis, 2006, Algorithmic Architecture (Oxford: Architectural Press).

45 Fraser, 1995, 66.

46 Fraser, 1995, 67.

47 Andrachuk, 2014, 196.

48 Fraser, 1995, 67.

49 Autodesk, 2024, Access at: https:// www.autodesk.com/.

50 Andrachuk, 2014, 197.

51 Andrachuk, 2014, 197.

Figure 5

Miles Dobson pioneers neural network computers, mirroring brain function, with visible logical structure and adjustable threshold levels in 1991. Despite complexity, it’s reducible to numerical logic.

(Frazer, 1995, 27)

In moral philosophy, an enduring inquiry revolves around determining which entities merit ethical consideration.52 It is commonly accepted that humans bear moral responsibilities, but should we extend such considerations to machines? When humans delegate decision-making to machines, are the design outcomes subject to the same moral scrutiny?53 Who bears responsibility for the moral legitimacy of the vast and complex decisions made by machines?54

I argue that machines, as objects, possess no ethical values; they are merely extensions of the human body and mind, designed primarily for task efficiency and human empowerment.55 However, transferring decision-making responsibilities to machines and absolving human moral accountability risks diminishing the moral significance of design. For example, utilizing parametric or mechanical ‘form finding’ contradicts the ethical decision-making process, as the ‘creativity’ of the machine is caused by the absence of information.56 Terzidis explained the parametric mechanical form generation process, that ‘an

algorithm is a process of addressing a problem in a finite number of steps… there are some problems whose solution is unknown, vague, or ill-defined… algorithms become the means for exploring possible paths that may lead to potential solutions’.57 The absence of defined parameters allows for the random generation of forms, with architects selecting from these instead of actively designing them.58 Although this process appears neutral and natural, akin to Darwinian natural selection, it precludes the evaluation of unknown parameters and the definition of ethically sound numerical values.59 Such form-finding surrenders human ethics to randomness and is irresponsible for design professionals. For end-users, their choices are limited to forms randomly generated by architects, potentially resulting in suboptimal solutions.60 Similarly, the concept of parametric ‘emergence’ is an unethical avoidance of human responsibility, as it implies forms could autonomously arise, obscuring the arbitrariness of their decisions.61 While computers offer vast choices in line with von Foerster’s ethic of expanding

6

Purposely uncomfortable airport design. Parametric machines prioritize powerful stakeholders’ interests, neglecting broader site forces and public experiences. (Sky News, 2024)

Figure

Figure

THIS LEADS TO DIMINISHING THE M OR A L VALUE OF DESIG N ING AS A UNIQUELY HUMAN ACTION

choices, there is no guarantee whether architects admit and disclose this ethos to the clients or the public.62

Moreover, machines functioning as extensions of humans inherit ethical values from their inventors, including potentially adverse ethics.63 Powerful machines, created by morally flawed and unaware humans, represent a menacing phenomenon, realizing and magnifying malevolent intentions, whether their human creators are conscious of the immorality or not.64 The mechanized brutality of World War II stands as a stark example.65 In terms of parametric design, machines enforce social injustice by selectively intaking and outputting information. Although social injustice existed long before mechanical decision-making, parametric tools allowed these ancient problems to persist.As mentioned earlier, parametric architectural design, integrated into the information flow, reflects the numerical values of financial, environmental, and social parameters.66 Parametric machines effectively include context parameters that align with the interests of powerful stakeholders while neglecting the

broader range of site forces and user experiences of the unprivileged general public.67 For instance, parametric BIM software effectively enables the construction of high-density housing without consulting the health implications of unit density.68 Studies by Loring, Gruenberg, a French study, and Madge have linked over-density to social disorganization, increased first psychosis admissions, family tension, and mental health standards.69 However, user-focused parameters like divorce rates and mental health rates are deliberately disregarded since they are not conducive to serving the financial benefits or environmental political reputation sought by stakeholders.

There is a mutual agreement between professionals, who ‘provide expert, ethical, and reliable services, maintaining high standards and training’, and society, which grants them ‘exclusivity, autonomy, fair compensation, and respect’.70 If machines take on the provision of these services, and decision-making loses its ethical property, it endangers the moral significance of designing profession.

52 David J. Gunkel, 2012, The Machine Question: Critical Perspectives on AI, Robots, and Ethics, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1-5.

53 David, 2012, 3.

54 David, 2012, 4.

55 Colomina, 2016, 78.

56 Kostas Terzidis, 2006.

57 Kostas Terzidis, 2006.

58 José dos Santos Cabral Filho, 2013, ‘The ethical implications of automated computation in design’, Kybernetes 42, no. 9/10, 1356.

59 Cabral Filho, 2013, 1356.

60 Cabral Filho, 2013, 1356.

61 Cabral Filho, 2013, 1357.

62 Cabral Filho, 2013, 1357.

63 Colomina, 2016, 134.

64 Colomina, 2016, 137.

65 Colomina, 2016, 138.

66 Andrachuk, 2014, 196-197.

67 Morteza Hazbei and Carmela Cucuzzella, 2023, ‘Revealing a Gap in Parametric Architecture’s Address of ‘Context’’, Buildings 13, no. 12, 3136.

68 Sjoerd Poelman, 1970, The Cob - A Parametric Approach for Designing Affordable and High Density Housing TU Delft Repositories, 1-3.

69 Robert Edward Mitchell, 1971, ‘Some Social Implications of High-Density Housing’, American Sociological Review 36, no. 1, 18-29.

70 Daniel Susskind and Richard Susskind, 2015, The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 22.

The relationship between humans and machines in the architecture field is constantly evolving, competing for the throne of decision-making. While machines, with their increasing intelligence and expanding role in design tasks, offer unparalleled efficiency and precision, they also risk undermining human creativity and ethical pursuits. Virtue design thinking risks distorting reality, overemphasizing computational outputs, and constraining human ingenuity. Additionally, ethically neutral machines can dilute the ethical significance of designing by transferring ethical responsibility to machines and exacerbate ethically flawed human intentions.

However, human designers can still guide technological innovation by revisiting the origins of self-design and exploring new avenues, such as designing logic, machines, and scripts.71 For example, Oxman calls for architects to move beyond traditional design practices and focus on higher-level design strategies, shifting from visual design to logical design.72 Frazer advocates for architects to employ machines imaginatively,

developing architectural concepts in a generic and universal form, with machines visualizing these human-formed ideas.73 He also encourages architects to create new customized programs and machines tailored to the specific needs of their design concepts.74 Schumacher believes that parametric machines should be continuously retooled and refined in response to social demands, suggesting that sociological needs should drive technological innovation.75 Mitchell calls for architects to maintain authenticity and integrity when facing complex conditions, resisting the allure of sensational but short-lived trends.76

Overall, architects should use machines imaginatively to avoid undermining human creativity and to preserve the ethical values of design as a uniquely human pursuit.

71 Colomina, 2016, 78.

72 Oxman, 2006, 262.

73 Fraser, 1995, 65.

74 Fraser, 1995, 23.

75 Schumacher, 2016, 1-12.

76 Mitchell, 2005, 10.

Andrachuk, James, Christos C. Bolos, Avi Forman, and Marcus A. Hooks. 2014. ‘The Price of a Paradigm by David Ross Scheer.’ In Perspecta 47, MIT Press, United States, 196-197.

Bernstein, Phillip. 2018. Architecture Design Data: Practice Competency in the Era of Computation. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Cabral Filho, José dos Santos. 2013. ‘The ethical implications of automated computation in design.’ Kybernetes 42, no. 9/10: 13561357. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1108/K-10-2012-0067.

Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

David, J. Gunkel. 2012. The Machine Question: Critical Perspectives on AI, Robots, and Ethics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Fraser, John. 1995. An Evolutionary Architecture. Architectural Association.

Hazbei, Morteza, and Carmela Cucuzzella. 2023. ‘Revealing a Gap in Parametric Architecture’s Address of ‘Context’.’ Buildings 13, no. 12: 3136. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ buildings13123136.

Mayne, Thom. 2006. Change or Perish: Remarks on Building Information Modeling. Washington D.C.: American Institute of Architects.

Meiresonne, Ellen, Donna Jeanne Haraway, Rusten Hogness, Atelier Graphoui, and Icarus Films. 2017. Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival. Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films.

Mitchell, Robert Edward. 1971. ‘Some Social Implications of High-Density Housing.’ American Sociological Review 36, no. 1: 18-29. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2093503.

Mitchell, William. 2005. ‘Constructing Complexity.’ In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Futures, Vienna, Austria.

Moe, Kiel. 2007. ‘The non-standard, un-automatic prehistory of standardization and automation in architecture.’ In 95th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, Fresh Air, ACSA Annual Meeting, 435-442.

Oxman, Rivka. 2006. ‘Theory and Design in the First Digital Age.’ Design Studies 27, no. 3: 229–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2005.11.002.

Poelman, Sjoerd. 1970. The Cob - A Parametric Approach for Designing Affordable and High Density Housing. TU Delft Repositories.

Schumacher, Patrick. 2016. Parametricism 2.0: Rethinking Architecture’s Agenda for the 21st Century. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons.

Susskind, Daniel, and Richard Susskind. 2015. The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Terzidis, Kostas. 2006. Algorithmic Architecture. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Figure 1 Gart, Kasia. 2022. ‘Art Masterpiece Artist’. LinkedIn. March 25. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ kasiagart_art-masterpiece-artist-activity-7114995931917295616-s-re/.

Figure 2 Mario Cucinella Architects. 2022. ‘Round Houses of Raw Earth: 3D Printing Sustainable Homes in 200 Hours’. ArchDaily. March 17. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/956854/ round-houses-of-raw-earth-3d-printingsustainable-homes-in-200-hours/.

Figure 3 Zhang, Wenxiu. 2023. Final Architecture Project, Week 2 Pin-up.

Figure 4 Frick, Ursula, and Thomas Grabner. 2022. ‘Adaptive Urban Fabric’. Evolo. Available at: https://www.evolo.us/ adaptive-urban-fabric/.

Figure 5 Fraser, John. 1995. An Evolutionary Architecture. Architectural Association.

Figure 6 Sky News. 2024. ‘Bank Holiday Air Travel Chaos’. Yahoo News. Available at: https://nz.news. yahoo.com/bank-holiday-air-travel-chaos-122600016.html.

The author acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in the writing process of this essay. ChatGPT was employed to assist with searching initial field of research, exploring relevant literature and correcting spelling, grammar and sentences. While ChatGPT aid the research process, all content was initially crafted and edited by the author.

Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

Inserted word count of the summary.

Inserted word count of the article.

Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

Researched and cited the required number of sources.

Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the front cover.

Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student

Name: Wenxiu ZHANG