8 minute read

Air and land worthy: Sherman Schueler flew combat missions in Vietnam but a crippled jet and love of farming brought him back to earth

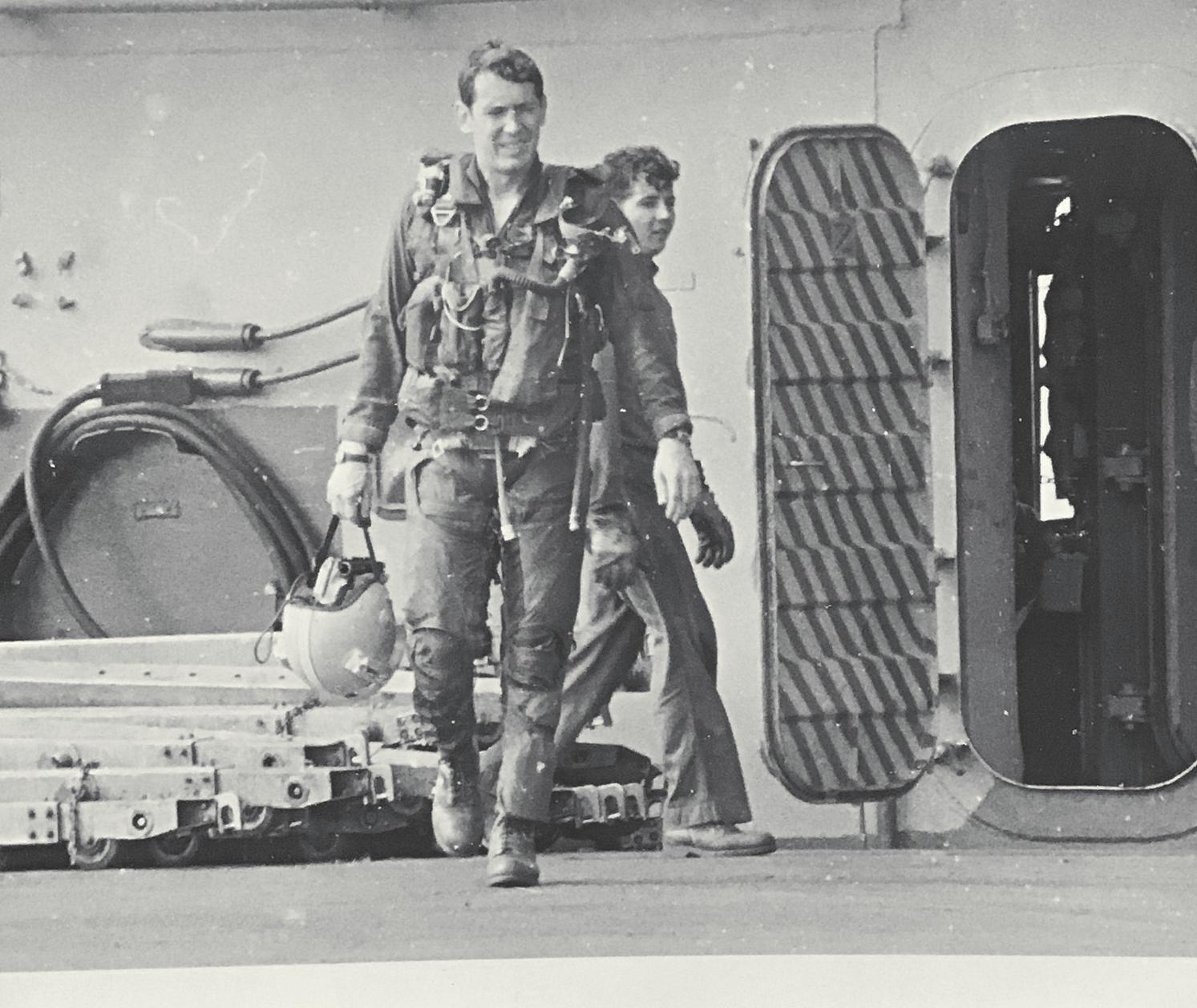

USS Shangri-La, Vietnam cruise July-December 1970. Sherm heads out to A-4 Skyhawk to fly bombing mission. Courtesy of Schueler family

BY SHERMAN SCHUELER as told to Rand Middleton

I grew up on a traditional family farm north of Svea. Dairy was the main income but we had pigs and chickens too. My Dad, Oscar, came out of the Depression and Dust Bowl-era with a strong work ethic. I was right in the middle of eight children. Our mom, Irma, was a homemaker. One thing unique about her is she insisted on seeing both sides of an argument.

Maybe that’s why I got the name Sherman Lee. While training in Meridian, Mississippi, I met a Marine from the South. When he learned my Christian name was Sherman Lee, he said “From now on, you’re Lee!”

I loved operating the farm machinery. The summer before I started first grade I hauled a load of oats back to the farm with a small B Farmall. I’m sure I was a pain to my older brother, Jerome, because I was always pestering him to let me drive the tractor.

I was the last graduating eighth-grade class from the Svea schoolhouse. In high school I maintained around a B- average without much effort. I tested into the accelerated classes but the teachers soon realized I wasn’t willing to put in much work, especially homework.

I remember meeting with a counselor following a battery of aptitude tests. Looking at my test results, he asked if I planned to go to college. I said I did not because I was afraid I couldn’t make it. I had come to believe college was much harder than high school, and anyways, I was more interested in farm work than homework. He said my test results were exceptional adding that “If you can’t make it, who can?’

Sherm & Karen’s 50th wedding anniversary picture in June 2019.

Courtesy of Schueler family

Willmar Junior College was brand new and its easy availability was a break. I was in the second graduating class and went on to St. Cloud State earning a degree in economics with a minor in accounting.

With the Vietnam War ramping up, a roommate who was a Naval Reservist told me I should talk to a Navy recruiter. My love of operating machinery enticed me to test for both the Navy and Air Force to enter their respective pilot pipelines.

I had tested into the Navy Air program but had not committed when I visited with the Air Force recruiter. He told me if the Navy would accept me I should accept, but if I didn’t get in their air program, the Air Force would be a better choice sinceit had more career choices. I took my Navy physical in Minneapolis spring of my senior year and left for Pensacola, Florida, July of 1967.

Upward bound

People yelled at me as soon as I entered the INDOC building. I was naive enough to think as a college grad I’d be appreciated. But the harassment lasted the next week as they tore us down. It felt like prison.

A bright spot came the third day at mail call. It was a letter from my former girlfriend at college. I had ended our relationship because of the dangerous missions I might be involved in because of Vietnam. Well, she’s now been my wife for nearly 52 years.

Pilot training consisted of three phases. First a fairly traditional piston airplane which was a modified Beech Bonanza.

Next was a straight wing jet trainer to introduce us to jet aviation, but still a very docile airplane to fly. The last phase was a swept wing aircraft with flight characteristics similar to high performance fleet aircraft. Because of Vietnam, after only 12 months, I was commissioned a First Lieutenant Junior Grade six months before getting my wings.

The Navy assigned me to fly the A-4 Skyhawk and sent me to Naval Air Station Lemoore, California. The Skyhawk is a light attack bomber designed so as to fit many on a carrier. By comparison to modern fighters, it had fewer electronics and no computers. It was the last of the “kick the tire light the fire” and go fly. (The durable Skyhawk had a top speed of 645 mph, a range of 2,000 miles and could carry 5 tons of bombs, the Sidewinder missile plus 20 mm cannons. It was known as “Heinemann’s Hot Rod” after its designer).

Sherm’s family in 1952, Sherm is front row on left, 7 years old.

Courtesy of Schueler family

After five months training during which time Karen and I were married, I was sent to join the USS John F. Kennedy on station in the Mediterranean. In July 1970, I was sent to the Tonkin Gulf to join VA-152 onboard the Shangri-La. I would end up flying 55 to 60 sorties from the carrier usually over the Ho Chi Minh Trail (running from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia to South Vietnam). We got as low as 5,000 feet dropping our bombs. They shot at us with big guns but not the tracking surface-to-air missiles. (Senator John McCain III was flying an A-4 Skyhawk when he was downed over North Vietnam on Oct. 26, 1967, and spent over five years in various prison camps.)

Night flying off the carrier is always high adrenaline, especially during the dark moon phase.

The high transverse G’s experienced at launch would mildly uncage your head.

On a dark, clear night there were just enough lights on the water from a few boats that the sky and the water looked the same. The plane is left just hanging in the air on the verge of stalling and you better be good at monitoring your instruments because for a few seconds your body senses are unreliable.

My biggest fear would be to lose my altitude indicator on a night launch. Day flying off the carrier in good weather would get routine. But I was surprised when we came off the carrier to land in Alameda, California, how relaxing it was to see several thousand feet of runway in front of me instead of 300 feet.

USS Kennedy takes a 1969 maiden cruise in the Mediterranean Sea.

Courtesy of the Schueler family

Following two cruises, I was assigned stateside to VA-127 in Lemoore to an A-4 training squadron. Here I had a close call. I had just become an instructor and was out with my first student.

On our second training flight over a northern area of Los Angeles there was an explosion and the sound of the engine unwinding with very hot temperatures. We were at 24,000 feet and we started to glide east to get close to Edwards Air Force Base, an unpopulated area with long runways.

At 10,000 feet we were lining up the runway when the controls quit. I told my student to eject. I pulled the alternate handle between my legs to follow him out of the cockpit. It was a wild ride. We landed in the hills to the east of the dry lake bed where the space shuttles sometimes landed.

I was OK but the student broke a small bone in his ankle. Those emergency parachutes have a higher decent rate and it’s important to touch and roll to lessen the impact.

After returning home to Minnesota and the farm I flew a couple of years for the Naval Reserves near Detroit before the Navy moved the squadron to Virginia.

Joystick to hoe handle

After my cruises, Karen and I spent a year and a half living in California. We noticed that residents worked a five-day week then headed to the country, meaning either the mountain or desert.

So in July 1972, we decided to go back to the farm. We’d be living in the country while we worked.

The ag crisis of the ’80s was very tough, but we survived. A big help was that I was able to fly again joining Sun Country Airlines in 1986. There had been a glut of pilots when we left active-duty Navy in 1973 but

opportunities had now materialized. While flying for Sun Country, my brother Kevin and I expanded the dairy operation to a 250-cow herd with a freestall barn, parlor and dairy crops.

Our nutritionist held a masters in sustainable farming from Iowa State. He served many of the organic dairies in Minnesota so we became aware of the organic industry.

Sherm pre-flights an ejection seat before flying mission, USS Shanghai-La.

Courtesy of the Schueler family

In 2011, Schueler Farms left the dairy industry and went into commercial hay production. A side line to hay production was to raise grass-fed beef. We found a market for the beef at several Minneapolis outlets. Dealing with these meat managers I got a rude awakening. Emma, a thirty-something meat manager at Eastside Food Coop, suggested we attend the Grassfed Exchange in Rapid City, S.D. I expected to learn about feeding beef on grass without the use of corn. But there was so much more.

Painting by Eric M. Swenson, Willmar High School senior

Courtesy of the Schueler family

This was the 10th anniversary of this group and their motto is “Healthy soils produce healthy crops which produce healthy food.” This is a grassroots organization which originated from ranchers who took overgrazed, essentially barren land in the west, and made it productive with good soil management.

Karen and I found ourselves in a large group from all over the world. We ate with young farmers from New Zealand and visited with a New York Times reporter.

But most impactful to my sense of a farm was a report by a University of Minnesota doctorate student. She studied several metrics from a conventional corn and soybean farm with that of a diversified organic farm.

What stuck out was an analysis of a square-foot of soil from each farm in the lab. On the diversified farm she identified 117 living organisms and on the conventional farm she found 12.

When I shared my experience with Emma, I realized this 30-year-old meat manager knew more about my soils than I did after 50 years of farming.

I believe this is a message farmers need to recognize.

On the drive home I had a premonition that 50 years from now chemicals will be used very sparingly in the industry.

As a kid, I grew up on a farm that didn’t use chemicals, then farmed 50 years as chemicals became routine.

Our challenge now is to see if we can successfully farm in this new paradigm. If we can do it profitably, maybe we can be an inspiration for young farmers in our area.

In 2019 Schueler Farms was recognized as Conservationists of the Year by the Kandiyohi Soil and Water Conservation District.