6 minute read

Field-to-pantry business success

TAKING THE WHEAT FROM FIELD TO PANTRY

By Katie Pinke and Jenny Schlecht | Forum News Service

Growing up, the Sproule sisters didn’t necessarily spend a lot of time in the tractors on their family farm in northeastern North Dakota, though they spent some summers working as “gofers” or helping move equipment or bringing meals to the fields.

But the farm was always close to their hearts and minds. After time in Minneapolis-St. Paul for college, all three gradually moved back.

“I think, when you grow up in North Dakota, you always have a connection to the farm,” said Grace Lunski, 25 and the youngest of the three sisters.

Lunski and sisters Annie Gorder, 31, and Mollie Ficocello, 29, now play a variety of integral roles on the farm, not the least of which is a new effort to market crops from “field to pantry.”

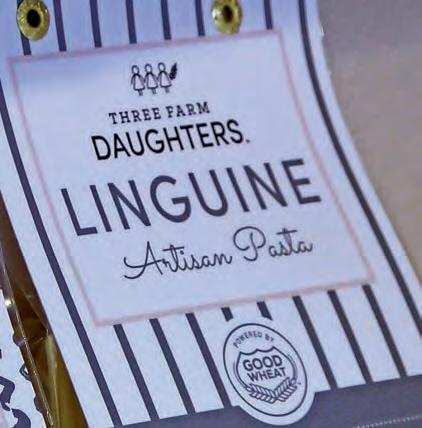

The sisters recently launched Three Farm Daughters, which takes the GoodWheat variety grown on the farm and transforms it into products like flour and pasta.

The company’s tagline, “No fillers, no dyes, no lies,” explains how they want their products to be seen.

“These are the attributes and the nutrition that we want to eat and feed our families,” Ficocello said.

But even more than that, the sisters see their business and story as ways to show the picture of modern agriculture and provide consumers the transparency they’re looking for about their food. “This was grown on our field. We put the seed in the field,” Gorder said. “This is what we did to bring it and raise it, and then we brought it to the elevator, the North Dakota Mill, and and we milled it, and now we’re bringing it to your pantry.”

One quarter at a time

Paul Sproule grew up working on his uncle’s farm in northeastern North Dakota, and he built Sproule Farms from scratch.

“He started one quarter at a time,” Gorder said.

In that time, Sproule wasn’t just raising crops but also his daughters. All three left Grand Forks to attend Bethel University in St. Paul. Gorder focused on finance and real estate, and she got a Master of Business Administration. Today, she and her husband run The Farm Agency, a farm auction agency. After Bethel, Ficocello completed law school at the University of North Dakota. And Lunski focused on human resources, communication and entrepreneurship; she started a cosmetics company at age 19 and also received an MBA. All three brought their skills back to the farm as they married and started their families.

Annie Gorder, Grace Lunski and Mollie Ficocello created Three Farm Daughters, a food company that uses ingredients from their family farm in Grand Forks, N.D.

Photos by Trevor Peterson

The Three Farm Daughters line of pastas are made of semolina flour and water.

Today, the Sproule operation is a large Red River Valley farm that grows sugarbeets, wheat, durum, hemp for grain, soybeans, corn, edible beans and potatoes. The farm has received Global Good Agricultural Practices certification, a designation that means they’ve had all aspects of their farm, from their agronomic The Three Farm Daughters practices to how they treat employees, audited line of pastas are made of and approved. A recent addition to the lineup is semolina flour and water.

Ficocello explains her father learned about GoodWheat and the company that created it, Arcadia Biosciences. She flew with him to Davis, Calif., to learn about the company’s approach to wheat and about its GoodWheat varieties that featured lower calories, higher fiber and lower gluten.

“We are the only farm in North Dakota that has been growing this wheat,” Ficocello said.

After Sproule Farms started growing GoodWheat, Sproule suggested that his daughters could take the crop and turn it into more. Working with their parents and other advisers, the sisters developed a business plan and went to California with their dad to pitch it to Arcadia Biosciences.

Though confident in their idea to market products from their farm to consumers like them — regular people who wanted to feed their families naturally healthy foods that they could trace — they were nervous to take the step.

Three Farm Daughters wheat flour is made with GoodWheat varieties, which offer lower calories and gluten and higher protein than other flours.

Gorder was pregnant at the time and Ficocello had recently had a baby.

Their father, Gorder said, talked them through it and calmed them down. He stressed that getting their idea turned down wouldn’t be the end of the world, in keeping with the way he’s always pushed them to go after their dreams and to remember that “failure isn’t fatal.”

Building for the future

The presentation with Arcadia Biosciences was a hit, and the sisters believe it was, in part, because they are building their company to be transparent and open, not just about their farm but also about who they are.

“They were like, yeah, this is great,” Gorder said. “And they said, this brand is just like you three girls.”

The business takes GoodWheat from Sproule Farms and from other farms in Idaho and turns it into flour and pasta with fewer calories and gluten and more protein. Along with the support of Arcadia Biosciences, Three Farm Daughters also has received ample support from North Dakota institutions. They received a $68,800 grant from the North Dakota Agricultural Products Utilization Commission and a $500,000 loan from the North Dakota Innovation Technology Loan Fund.

The products so far are being sold on a small scale, on the Three Farm Daughters website, in Hugo’s stores and soon in Hornbacher’s stores. As demand grows, they want to expand into the Midwest. And with that will come the ability to market not just their own wheat but that of their neighbors, too.

“If 100 million people are buying flour,” Gorder said to laughs from her sister at the far-flung goal, “we’re going to need a lot more farmers to grow this wheat. So we’re hoping we can really launch our seed platform and we can contract with growers. And we’d love to have it in the Red River Valley and kind of go from there.”

They’re working with local chefs to develop recipes and find ways to use the products. The low gluten means the flour doesn’t work for traditional bread recipes, but it can be used in things like pull-apart rolls, pizza, naan, cookies, cakes and brownies, Lunski said. They also want people who use their products to message them about how they use it and their recipes.

Also important to them is the small list of ingredients on their products. The pasta is just semolina flour and water, Gorder said.

“We’re trying to show that this natural wheat is actually nutrient dense and is actually good for you,” she said.

And they’re also trying to highlight all the things they know and love about agriculture, things like technology and the family connection, as well as to show people that modern agriculture doesn’t necessarily look like consumers’ images of farmers. Instead, it might look like three well-educated daughters finding ways to help diversify their farm and add value to what is grown there.

“Ag is near and dear to our hearts. I know it’s near and dear to many others,” Ficocello said.

Mollie Ficocello, Annie Gorder and Grace Lunski are sisters who are raising families, staying involved in the family farm and creating markets for that farm through their business, Three Farm Daughters.

Three Farm Daughters flour is best suited for things like cookies, as it has a low gluten content that is not ideal for bread baking. Pictured are Mollie Ficocello and Annie Gorder, two of the three “farm daughters.”