'Nobody listens': Inside disabled students’ Western experience

LUCAS ARENDER COORDINATING EDITOR

Ashton Forrest has been a Western student for almost half of her life.

It wasn’t until the diagnosis she received during her fourth year that she understood why many students with disabilities feel they don't belong at Western University.

Forrest was quick to speak out once she discovered the accessibility barriers ingrained in the school — from an overwhelmed accommodations system to inaccessible spaces on campus. Eventually, the administration hired her in an accessibility consultant role, but after months of feeling her recommendations were being overlooked, she began to feel tokenized.

She believes the school used her “disability, Blackness and femininity” to endorse its accessibility projects.

Forrest’s experience, as both a disabled student and an employee of the school, shows Western's struggle to address barriers that continue to exist for students with disabilities on campus.

A Western professor’s research showed 60 per cent of disabled students surveyed at the university experience fatigue from trying to navigate campus. A 2021 external review revealed Western had the worst ratio of trained advisors to students with disabilities of any post-secondary school in the country that disclosed their data.

Based on interviews with students, advocates and faculty, as well as email correspondence between students and university administrators, this is a portrait of an institution grappling with making the “Western experience” an inclusive one.

Forrest is a master’s student, disability advocate and member of London’s mayor’s list of honourees, who came to Western in 2004 as an able-bodied student. Four years into her degree, she was diagnosed with scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that hardens the skin and causes issues with blood vessels and internal organs. The disease damaged Forrest’s lungs, eventually making her rely on a scooter for transportation.

Since the diagnosis, she has dedicated her life

to eliminating the barriers she discovered as a disabled student. From inaccessible washrooms, classrooms and o ce spaces, to an an accommodations system that struggles to meet student needs, she says she and other advocates have seen little change over the past decade and a half.

Following a critical external report on Western’s accessibility practices in 2021, Forrest was o ered a consulting job with the school. She was warned by friends and fellow advocates it was Western’s way of silencing her public criticism of the university. But she wanted to make change from the inside, and ultimately took the job.

It didn’t take long for her to realize a seat at the

table doesn’t always mean a voice that is heard.

Forrest says that, while Western consulted her, the school often failed to listen to her recommendations. She used the example of the recent D.B. Weldon Library renovations, a project she consulted on, where there remains a number of barriers in the building Western spent $15-million redesigning.

Forrest explains that in spite of recommendations to make the washrooms accessible during the stakeholder engagement period, they remain inaccessible to herself and many other students requiring mobility aids.

Many washrooms on campus don’t have auto-

mated doors and are inaccessible for students in scooters and wheelchairs. While they may have stalls that are “accessible” inside, the actual entrances to most washrooms on campus remains a barrier.

Fourth-year computer science student Alaa Abdulsada, a disabled student who requires a mobility aid, says even the washrooms with accessibility signs above them are not truly accessible.

“They put the label of the wheelchairs on [the washrooms]. But there is no door opener,” he

CONTINUED ON P4

Muslim students' push for prayer spaces continues

JESSICA KIM STAFF REPORTER

The Undergraduate Engineering Society voted to set up a temporary prayer space in the Claudette Mackay-Lassonde Pavilion at their Mar. 13 meeting — the latest gain in the Muslim Students’ Association’s decades-long advocacy e ort for space to practice their faith on campus.

Engineering will be the second faculty at Western University to get a new prayer space this semester, following the Ivey Business School’s Mar. 6 announcement of a new a pilot program for a Muslim prayer space.

Before this month, there was only one Muslim prayer space on campus — in the basement of the University Community Centre — and one interfaith prayer space in Middlesex College. This left

some students with classes far from these buildings praying in whatever space was available on campus, regardless of its suitability for religious practice.

Finding prayer space has long been a challenge for Muslim Engineering students due to their course load and buildings’ locations. The Gazette reported in February that dozens of Muslim students gather in the Amit Chakma Engineering

Building stairwell and take turns praying in the space at the designated times throughout the day.

Mohamed El Dogdog, a second-year software engineering student and one of the students who prayed in the stairwell last month, said the walk from the ACEB to the closest designated prayer room, in the UCC, is “a very, very far trip to go to

MARCH 16, 2023 VOLUME 116 ISSUE 8 since 1906 NEWS CULTURE From Western to TIFF: Cameron Bailey talks representation, diversity and love for movies How to grocery shop on a student budget P7 Science class needs to change for ChatGPT SPORTS Tim Hortons Brier curling championship wraps up in London with Gushue win P6 OPINION P2

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Ashton Forrest on the Mezzanine level of Weldon Library, March 10, 2023

University Community Centre Rm. 263

Editorial editor@westerngazette.ca

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

COORDINATING EDITOR (VIDEO AND FEATURES)

LUCAS ARENDER

COORDINATING EDITOR (CULTURE AND SPORTS)

BIANCA COLLIA

ART DIRECTOR CASSANDRA KACZMARSKI

NEWS ANDY YANG

ESTELLA REN ADSHAYAH SATHIASEELAN SONIA PERSAUD

CULTURE LAUREN MEDEIROS

CAT TANG DANIELLE PAUL

SPORTS MILES BOLTON

KIERAN DROVER RYAN GOODISON

How to grocery shop on a student budget

ESTELLA REN NEWS EDITOR

WithCanadian grocery bills expected to rise even further in the spring, now is the time to learn how to shop smart.

The Canadian monthly average retail price report indicates many grocery items have experienced double-digit per cent price growth, exceeding the typical winter rise, according to CBC Loblaws also warned its No Name grocery items would see price hikes in the coming weeks after it ended its three-month product price freeze.

How can a student budget survive these grocery prices? Here’re some strategies for finding bargains in London.

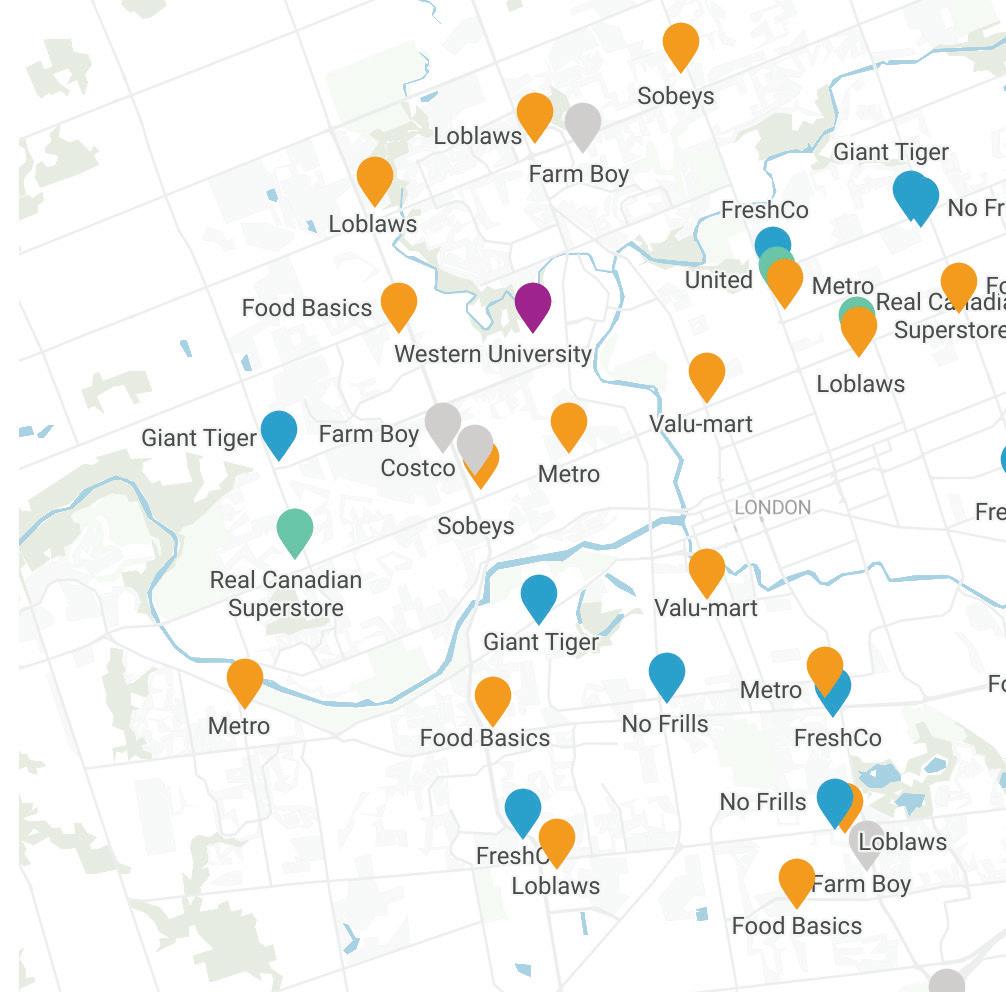

STUDENT DISCOUNTS

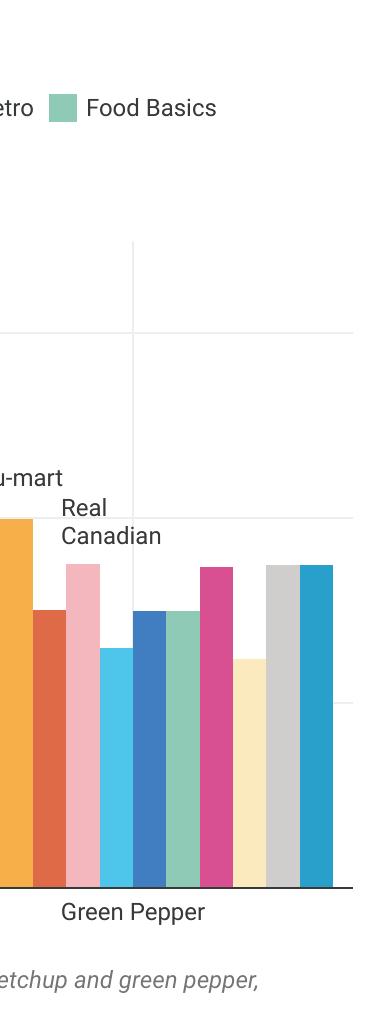

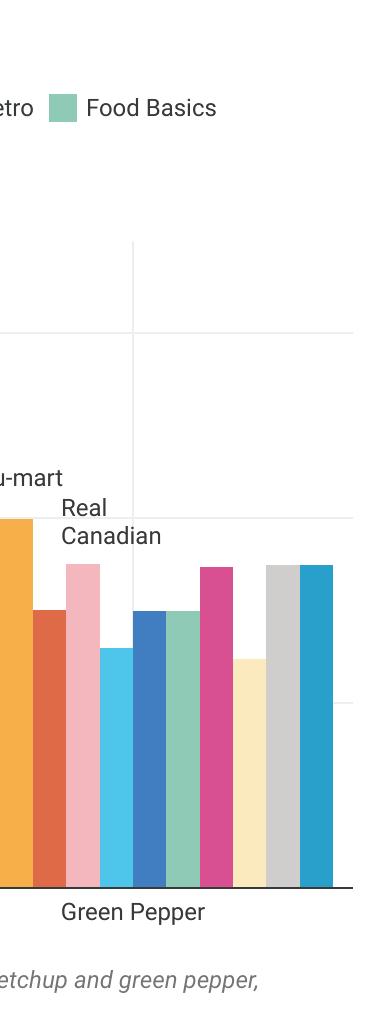

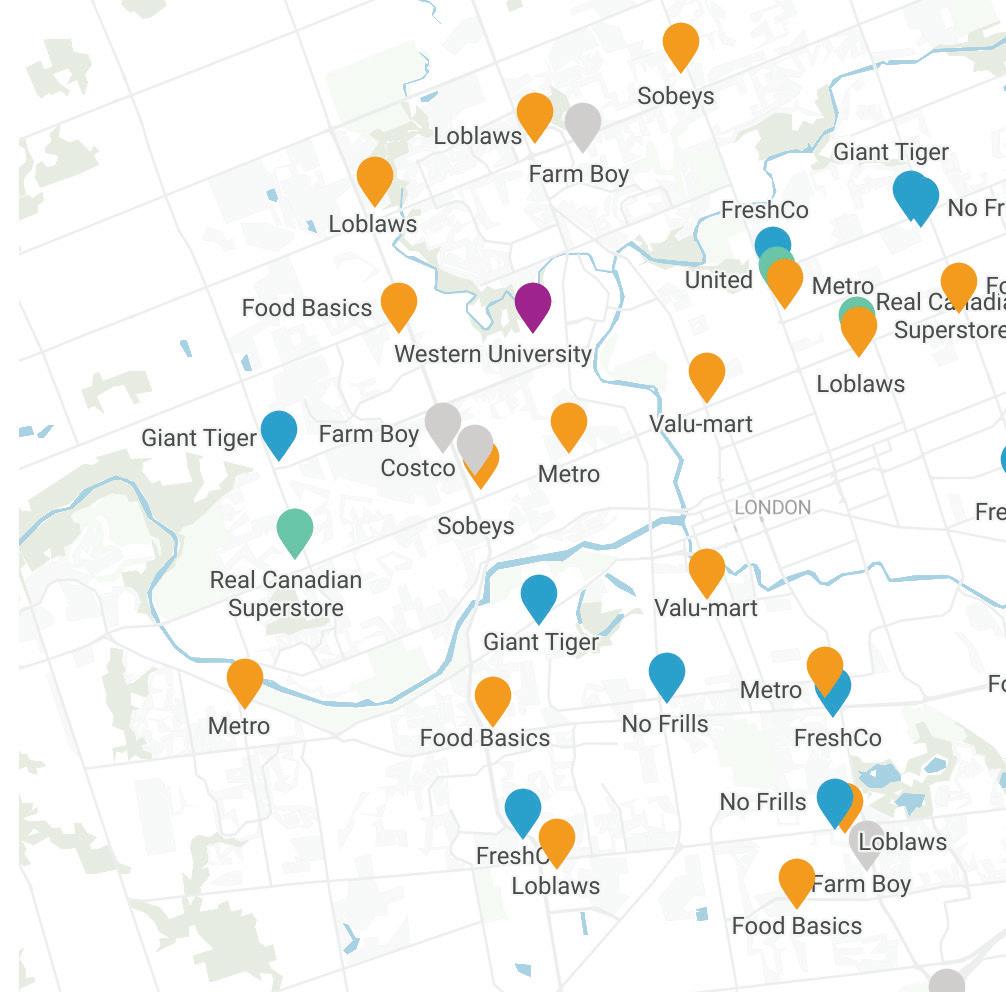

Tuesdays tend to be when students get the best grocery prices. Seven main grocery stores in London o er a 10 per cent o student discount on Tuesdays, including Sobeys, Valu-mart, Real Canadian Supermarket, United Supermarket, Metro and Food Basics.

United Supermarket also o ers student discounts every Wednesday and Metro has two additional student discount days — Wednesday and Thursday.

PRICE COMPARISONS

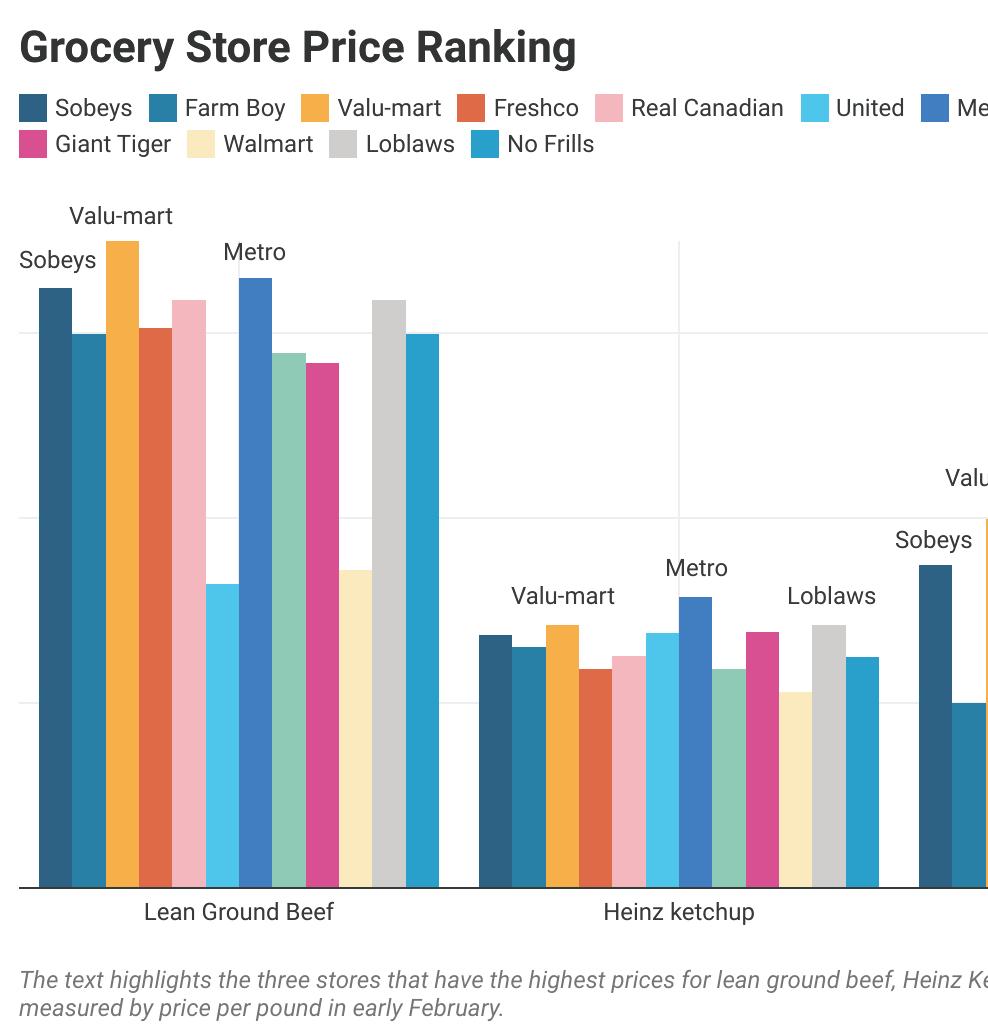

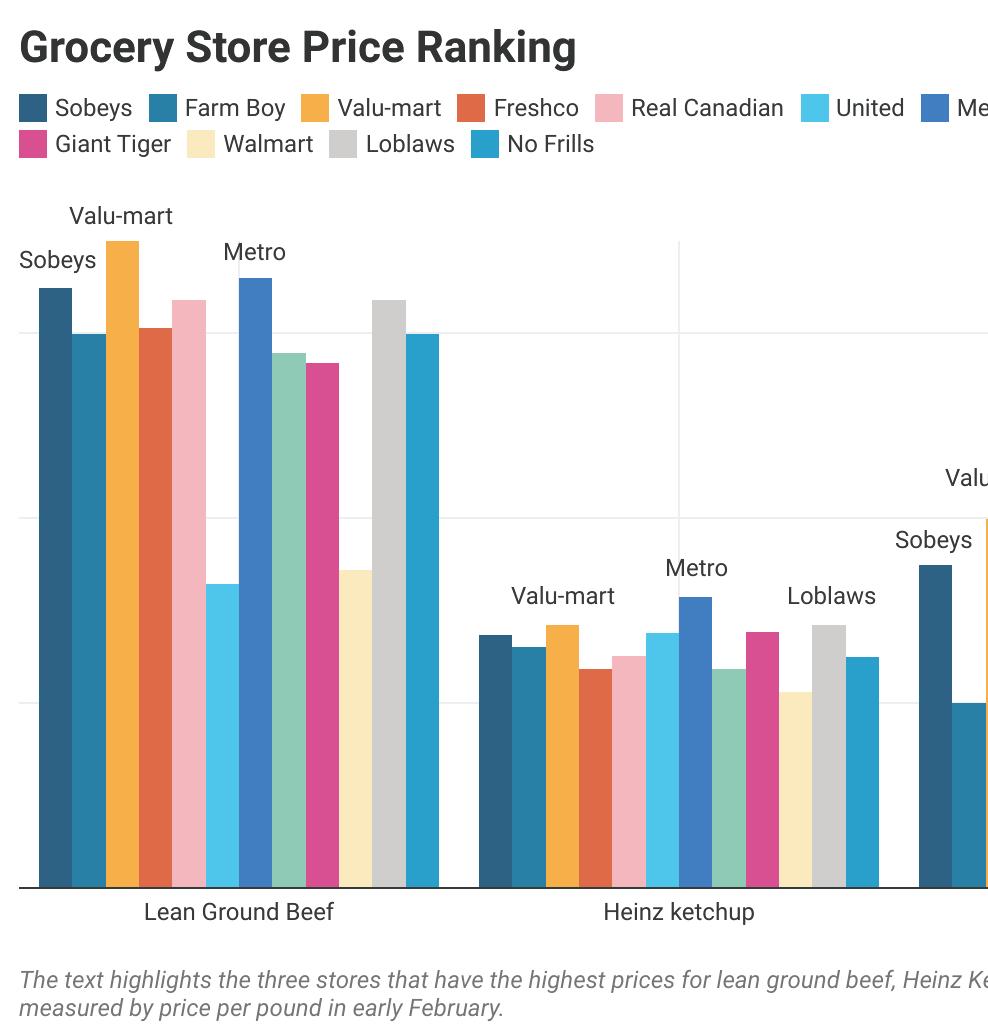

Commodity price varies at di erent grocery stores. The Gazette compared the di erent prices of three random products that could be found online: generic lean ground beef, Heinz Ketchup and a single green pepper at major grocery stores in London.

OPINIONS

JORDAN BLOOM HANNAH ALPER

STAFF REPORTERS

JESSICA KIM

VERONICA MACLEAN

COPY ELIZABETH HART SCOTT YUN HO

GRAPHICS REBECCA STREEF

KAT HERINE G UO

PHOTO SOPHIE BOUQUILLON

VIDEO REBECCA BARTKIW

MADELEINE MCCOLL ROMANO WATT MINA AHMAD

SOCIAL MEDIA

ELIZABETH HART

PE’ER KRUT

CHIARA WALLACE

The three commodities’ prices at Valu-mart, Metro, Loblaws and Sobeys were at the relatively high end, while Real Canadian Superstore, Giant Tiger, No Frills, Food Basics, Farm Boy and Freshco were average among London grocery stores. Walmart and United Supermarket were on the more inexpensive end.

PRICE MATCHING

Price matching is a policy where certain grocery stores will adjust a product’s price if a competitive store o ers a lower price for the same item. The item must be the same brand, type, size and measurement.

Not all stores price-match. London shoppers can find price matching at Freshco, Real Canadian Superstore, United Supermarket, Giant Tiger and No Frills. Notably, Freshco only matches prices at Walmart, No Frills, Food Basics and Real Canadian Superstore.

By showing cashiers a physical or digital advertisement with valid dates, shoppers can receive the same lower price o ered at another store in the same week. They can even request a refund for the di erence between what they paid and what

the other retailers are o ering. While checking the weekly grocery flyer can seem like a daunting, time-consuming task, mo-

bile apps which collect deals and flyers from local stores such as Flipp and Reebee can make it easy for shoppers to find the best o ers.

Tuition freeze extended for third year, excludes out-of-province students

ADAM TAIMISH NEWS INTERN

The Ontario government has extended a tuition freeze on colleges and universities for in-province students through the 2023-24 school year.

The tuition freeze does not apply to out-ofprovince domestic students, who will see their tuition increase by over 10 per cent next year. This is the first increase for out-of-province students in three years. The freeze also does not apply to international students.

The extension is the third consecutive tuition rate freeze for Ontario students since the provincial government decreased tuition by 10 per cent for the 2019-20 school year.

Within one day of the decision, Western University announced tuition would increase for out-of-province students. In an email to out-ofprovince students, Western’s Student Financial Services said tuition for full-time students would

increase by $619 from the current $6,050 in the 2023-24 summer, fall and winter semesters — a 10.2 per cent increase.

The significant increase is partially a result of an increase for 2022-23 that Western decided to delay implementing. The school was allowed to increase tuition by five per cent this past school year but chose not to due to the decision’s late timing.

As of the 2020-21 school year, 8.4 per cent of incoming first-year students were out-of-province domestic students.

“I could understand it if it were a general thing that applied to everyone due to the economy and the extreme inflation that has been happening recently, but I don't feel great that it is just for outof-province students,” said Sarah Hill, a first-year commercial aviation management student from British Columbia.

The year-over-year inflation rate in Canada as of January is 5.9 per cent — nearly triple the ac-

cepted value for healthy inflation.

Hill said she believes the government’s change is unfair. She outlined extra costs associated with going to university as an out-of-province student, such as flight tickets and other travel expenses.

“My family is already struggling to a ord all the costs of university — not just tuition — but the added-on costs such as the residence prices, rent for next year, meal plan, books and spending money,” Hill said. “Having the added extra cost of tuition is a stress factor for my family, since it takes money out of the small amount of disposable income we already have.”

In 2022, Western reported a $127 million surplus. Less than 40 per cent of their revenue came from student fees. The university has reported more than a $570 million surplus since the COVID-19 pandemic began in the 2019-20 school year.

Western did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

VOLUME 116, ISSUE 8

MARCH 2023

Western University London, ON, CANADA N6A 3K7

HOPE MAHOOD

DEPUTY EDITOR ALEX MCCOMB

articles, letters, photographs, graphics, illustrations and cartoons published in the Gazette both in the newspaper and online versions, are the property of the Gazette By submitting any such material to the Gazette for publication, you grant to the Gazette a non-exclusive, world-wide, royalty-free, irrevocable license to publish such material in perpetuity in any media, including but not limited to, the Gazette’s hard copy and online archives. @UWOGAZETTE @WESTERNGAZETTE / WESTERNGAZETTE /UWOGAZETTE / WESTERNGAZETTE Send us an email at managing@westerngazette.ca THIS COULD BE YOU!

University’s o cial student newspaper since 1906 WESTERNGAZETTE.CA @UWOGAZETTE EDITORIAL SUPPORT MANAGER DAN BROWN GAZETTE CONTRIBUTORS LAILA EL ATTAR MONIQUE FLEMING EMILY GALUZZO MANAN JOSHI ADAM TAIMISH NEWS | P2

MANAGING EDITOR SARAH WALLACE All

Western

ESTELLA REN CREATED WITH DATAWRAPPER

Muslim students' push for prayer spaces continues

CONTINUED FROM P1

and then you have to come back to classes.”

“If you have a class back to back there's really no space to catch the prayer.”

El Dogdog explained, in Islam, women and men are also required to pray separately, which the stairwell does not allow for. He said there is not enough room for one gender, let alone multiple.

Women also have an added layer of challenges for prayer. Second-year software engineering student Aya Marie explained, for a Muslim woman to pray, they need to be covered — a prayer room is important for storing items like hijabs and skirts.

“A lot of my friends don't wear hijab. So usually they'd have to walk all the way to UCC, they can't even pray with us at the stairwell,” said Marie. “It's a pretty far walk, especially in the winter and between classes.”

And for those in the stairwell, prayer feels dangerous.

“It puts us as an open target for anyone with any islamophobic thoughts,” fourth-year software engineering student and MSA vice-president Abdullah Al Jarad said, referencing the deadly attack on the Afazaal family in London in June 2021.

After MSA and students praying in the stairwell spoke out to the Gazette and CBC last month, Western’s total campus prayer spaces doubled to four.

The MSA says it is happy with the additions as a first step.

“It opens the door for a lot of new things,” Al Jarad said. He noted there are still e orts to be made in other faculties and buildings across campus.

Vice-president of public relations for the MSA and fourth-year medical sciences student Maryam Oloriegbe said despite progress, the MSA will “still encourage students on campus to have continued dialogues about prayer spaces.”

“We're still going to continue to raise the voices of the Muslim people on campus. That's our job as an MSA to represent them,” said Al Jarad.

When asked for an update on the university’s progress, director of wellness and wellbeing Terry McQuaid said in a statement to the Gazette that “Western continues to work at identifying additional prayer spaces on campus to supplement

the Multifaith Centre for Spiritual Program and Practice and the Muslim Prayer Room at the UCC.”

Al Jarad emphasized the university and its Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion are key to finding space for prayer on campus. He said the MSA “hope[s] to continue these conversations all throughout campus with the university, student groups, and EDI, to have prayer room facilities available for all students.”

Prayer spaces and multi-faith rooms, or lack thereof, have long given rise to controversy at Western.

The Gazette reported on significant confusion surrounding a new campus multi-faith space on the second floor of the UCC in October 2012, with students reporting they were unclear on its purpose. Three months later in January 2013, the University Students’ Council proposed moving the multi-faith space to the Gazette o ce. The proposal was met with significant opposition from student leaders in religious communities and was never implemented.

After that proposal was withdrawn, similar confusion around the original multi-faith space’s guidelines was reported in the fall of 2013, as the USC considered letting non-faith groups use the space for programming. In response, then MSA president Amir Hage advocated for a larger, Muslim-specific prayer room.

In November 2014, Western announced the Muslim prayer room’s relocation, along with the Chaplains’ Services o ce, from University College to the UCC.

Following the announcement of the move and subsequent closure of the UCC multi-faith prayer room, five university chaplains resigned in protest, saying Western’s actions were “unjust and discriminatory.” The dispute made local and national news.

Now, with four prayer spaces on campus, the push isn’t over for the MSA.

“Muslim students across any faculty … should be able to have prayer space accessible to them in their own building,” said Oloriegbe.

“Prayer is a non-negotiable thing. It's not something you can just put o .”

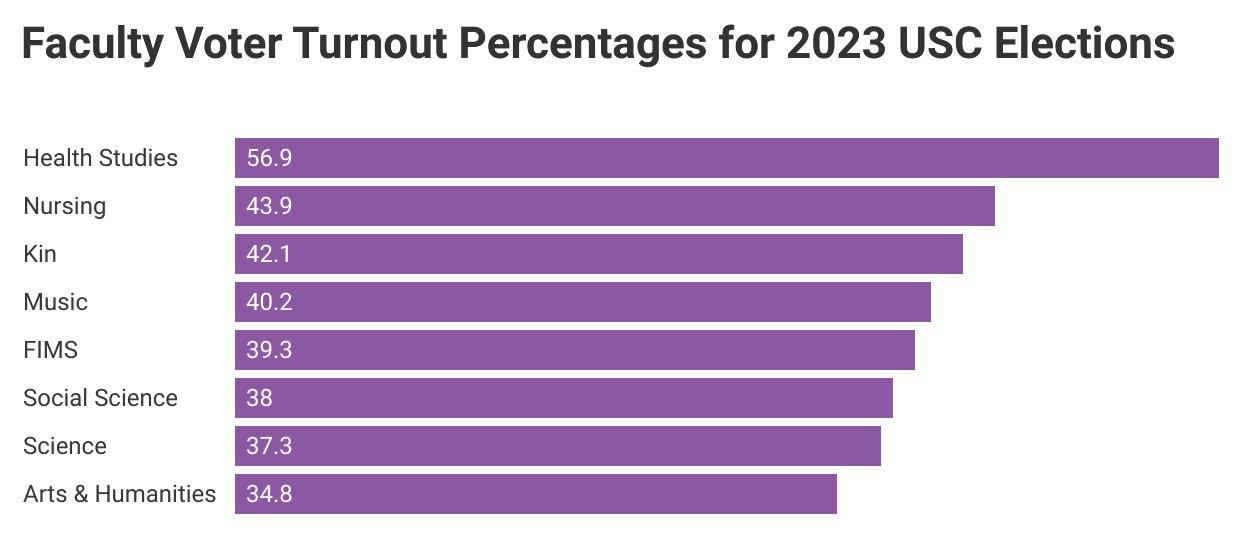

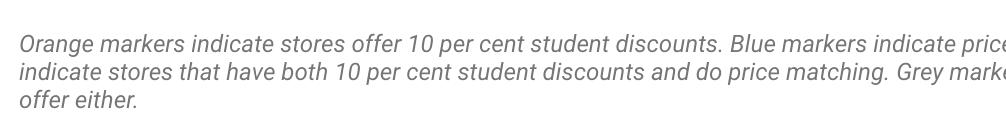

FIMS, Arts and Humanities student council presidential roles remain unfilled, by-election pushed to fall 2023

LAILA EL ATTAR NEWS INTERN

Presidential positions on the FIMS Students’ Council and the Arts and Humanities Students’ Council will remain unfilled until next fall after last month’s University Students’ Council election saw no candidates run for either roles.

This is the second year in a row no students have run for president of the Faculty of Information and Media Studies Students’ Council. The current Arts and Humanities president Sydney Turner ran unopposed last year.

Presidential by-elections for the unfilled roles will run in the fall semester.

“It’s unfortunate that there aren’t currently candidates for these positions, but I’m looking forward to them being filled in upcoming by-elections,” said University Students’ Council president Ethan Gardner.

The six other student council presidents elected on Feb. 13 ran unopposed. Engineering and Ivey Business School have separate elections which are not administered directly by the USC’s elections governance committee. These councils

fared better with two and five candidates running for president, respectively.

AHSC’s highest number of presidential candidates in USC elections since 2018 was two in 2019. FIMSSC’s highest in the same timeframe was three in 2020.

In comparison to other non-professional

school faculties, Arts and Humanities had the lowest voter turnout this year.

The AHSC council representative position is also unfilled this year for the first time since the 2019 USC elections.

“Unforeseen circumstances led to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities not making it to the ballot

for the spring election,” said Turner. She added that the faculty is working hard towards developing its leadership roles in hopes of having a strong representation in the USC next year.

Current FIMSSC president Sara Paulo said the lack of interest in student leadership at FIMS is both disappointing and concerning. Paulo believes this was a result of students being intimidated to take on a large role like presidency.

“As a smaller faculty it is important that we have leaders to represent us and our voice to the USC,” said Paulo. “I want students to know that taking on the responsibility as president or councillor is truly a rewarding experience.”

Despite struggles to elect leaders in these two faculties, Gardner remains positive about the future of student governance after this year’s historic 34.6 per cent voter turnout for the USC presidential election.

“We look forward to continuing the USC’s long-standing tradition of having involved and passionate students make their voice heard on campus,” said Gardner.

NEWS | P3

LAILA EL ATTAR CREATED WITH DATAWRAPPER

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Prayer mats in the Amit Chakma Engineering Building stairwell, Jan. 18, 2023.

‘NOBODY LISTENS’

Inside disabled students’ ‘Western Experience’

says. “So how am I supposed to go in?”

Abdulsada says he often cannot go to the washroom in the same building he has class in. On top of this, he says most of his lecture halls do not have automatic doors, forcing him to rely on his professor to let him in and out of his class.

“I have to stop the prof from teaching to open the door for me, which is, you know, in front of 250 students, just so embarrassing.”

He says he’s emailed accessible education, Western administration and went in-person to the accessibility department in an e ort to get automated doors installed but was brushed o at each turn.

“I’ve reached the point where if I [speak up] or don’t it's the same,” he says. “I don't know who to go to … I feel like I’m always humiliated, ignored. Nobody listens.”

The barriers Abdulsada has faced with accessible classrooms and study spaces has been a major point of advocacy for Forrest.

One of the projects she advocated for as a student was Weldon’s Access Lab. This was supposed to be an accessible study space for students with disabilities, and while the room was eventually converted from a storage room in 2013, Forrest says the capacity was between 15 to 20 students at a time, each of whom were only permitted to be in there for three hours at a time.

Western said in a statement to the Gazette that “the Accessible Education Lab has undergone extensive renovations that are scheduled to be completed during the winter term … The physical space comfortably hosts 20 individuals,”

According to the 2022 Western equity census, just over nine per cent of students indicated they have a disability. Of the student respondents, 14 per cent of them identify with a physical disability.

That would mean that the capacity in the new Access Lab is still less than four per cent of Western students who identify with a physical disability.

For the past three years, she has dealt with daily headaches, migraines, severe fatigue, neuropathy as well as osteoarthritis in her back and both wrists — all the result of a disability that has taken away the lion’s share of life’s freedoms. She even struggled to get through the entirety of a Zoom lesson.

“I think it’s safe to say I have zero social life,” Adrianovska says. “I don’t know if it's genuinely my personality or if being sick for so long and not knowing it altered my perception of what I would enjoy and what I wouldn’t.”

Adrianovska, who graduated in 2021 with a degree in German studies, was diagnosed in 2019 with a rare adrenal gland tumour, a pheochromocytoma — which is a type of tumour which releases dangerously high levels of adrenaline — causing what she describes as debilitating pain.

While virtual learning posed challenges to students and educators alike, not having to attend classes on campus was a saving grace for Adrianovska in light of her diagnosis. She says she often needs several naps daily to deal with the pain, fatigue and side e ects of her medication, making a typical class schedule impossible to manage.

The solution Western o ered Adrianovska: apply for a tuition refund or defer her studies until she’s able to attend class in-person. She wasn’t the only one to get this email.

Western said in a statement to the Gazette in August their policy is “when a student is unable to access a course, alternatives are reviewed in conjunction with academic advisors to find an equivalent that will meet the student’s needs and fulfill program requirements.”

Western did not respond to a request for comment about the options o ered to Adrianovska at time of publication but said, “the university is not able to discuss individual student cases.”

“If it is possible to do online learning when all people, meaning able-bodied people, are a ected, then this must remain an option for those who need it as a basic accommodation,” Adrianovska says. “We know it’s possible, it’s just a matter of if the administration wants to accommodate or not.”

This sentiment is echoed by third-year computer science student Jonathan Alexander, a mature student who requires accommodations for his ADHD.

Forrest spent less than a year in the consulting job with the school, growing increasingly frustrated as the administration failed to implement many of her recommendations. Forrest says that it was after she began to feel tokenized by the school that she decided she had to resign. She says if the school doesn’t respect her, that she has no business being in Western’s corner.

While her Western classmates type away at their laptops in lecture halls, have lunch with friends between classes and grab drinks at the Spoke, Layla Adrianovska lies in bed at home, fighting the chronic pain that has overshadowed her university experience.

“Because of the fatigue and damage the adrenaline has done to my heart, it makes it hard for me to stand and walk more than a few minutes,” she explains.

“My back pain is so severe that I can’t sit at a desk for more than 15 minutes.”

Although she was able to continue her degree online throughout the pandemic, Adrianovska says Western would not provide her with virtual accommodations after classes were moved back in-person. After reaching out to Western Health and Wellness last year, explaining her disabilities would preclude her from attending a class of hers that was not o ering a hybrid option, she was told by an administrator Western is “an in-person campus for the remainder of the term.”

Alexander says, even before the pandemic, he struggled to receive accommodations — specifically, extra time on assignments and exams. Over the past two years, he’s exchanged dozens of emails with multiple levels of Western administration, student experience and accessible education departments, advocating for himself and others.

“This is not just a post-COVID thing. This is reality for us. This is what we've been experiencing since day one of joining the university,” he says.

Last year, Alexander applied for a memory aid through accessible education, which among other accommodations, provides him extra time on evaluations. He says the process required him to get professional opinions and documentation

NEWS | P4

CONTINUED FROM P1

- 2021 Western external acessibility review

“What is needed beyond accessibility policies, frameworks and strategies is attention to campus climate for [students with disabilities]. This is especially important in light of SWDs strong perception that they do not belong at Western.”

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Ashton Forrest trying to access the accessible washroom on the Mezzanine level of Weldon Library, Jan. 12, 2023.

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Accessible bathroom sign with braille, Weldon Library, March 14, 2023.

from four di erent specialists, including his physician and therapist. He paid for all of those evaluations, a total of $2,400, out of pocket, but was told that it was not enough.

After weeks of back and forth with accessible education, and an additional letter of recommendation from his therapist, he was granted accommodation.

But after months of negotiating his access needs, Alexander found his mental health deteriorated. He was advised by his therapist to take a break from school for his own well-being. Although he made his accessibility counsellor aware of his absence and the reasons for it, he fell behind in his classes and ultimately failed four courses.

Those grades remain failures on his transcript. Western did not respond to a request for comment regarding Alexander’s situation or the status of his failed grades.

He described this cycle of exhaustion as “access fatigue.”

Access fatigue is a common symptom students with disabilities experience navigating inaccessible spaces. Research conducted by Western anthropology professor Kim Clark revealed how common access fatigue can be to students. Many students with disabilities that took part in the study explained they continuously have to negotiate their access needs throughout the school year.

The study surveyed 83 disabled students from across campus. Sixty per cent of the study’s participants said they experience some sort of access fatigue at Western.

The study also shone a light on the undiagnosed students with disabilities at the university.

Clark acknowledged the percentage of students with disabilities is likely greater than the nine per cent figure recorded in a 2022 Western census, given other research has shown that a quarter of Canadian university graduates identified as disabled.

The overarching conclusion of Clark’s study is not only that the university needs to adopt more accessible teaching strategies, but that it must usher in a more welcoming environment.

A significant factor contributing to disabled students’ access fatigue is the lack of trained support sta . The external accessibility review of Western published in 2021 revealed why it might be di cult for some disabled students to access the accommodations they need.

Caseload, or student-to-sta ratio, is a metric the Inter-University Disability Issues Association looked at across Ontario universities to evaluate the ratio of trained advisors to students registered with a disability. Of the 14 institutions who responded to the survey in 2018-19, four institutions had caseloads ranging from 101 to 200 students per advisor and four institutions had caseloads ranging from 301 to 400.

Only one school reported caseloads above 500 students per advisor — Western.

The report’s authors went on to explain high caseloads in the 500-plus range make it extremely challenging for sta to meet their duty in accommodating students with disabilities. The accessibility challenge is not only the barriers that exist from a policy standpoint at Western, the 2021 independent review concluded, it is also about the message the lack of progress sends to disabled students.

“The reviewers would like to suggest that what is needed beyond accessibility policies, frameworks and strategies is attention to campus climate for [Students With Disabilities],” the review reads. “This is especially important in light of SWDs strong perception that they do not belong at Western.”

University president Alan Shepard told the Gazette in a January interview this is not an issue specific to Western.

“I think all institutions are struggling with increased requests for accommodation,” Shepard said. “I wouldn't say it's exclusively the Western accessibility department that faces this barrier. There aren't enough resources for us to draw on.”

Shepard says Western continues to invest in the accessibility department, but he admitted he wasn’t aware the caseload number was as high as it was.

“We regularly review sta ng levels in relation to students accessing our services and have added two Accessible Education Counsellors to the team since 2021,” Western said in a statement to the Gazette. The university did not provide updated caseload numbers for the past four years.

Shepard says the school has made investments in accessibility projects, specifically noting the open space strategy and the UC Hill renovations. He feels strongly that students with mobility aids are able to navigate campus safely.

“These are important issues to us.”

Alexander eventually reached his boiling point and undertook what he considers to be his last course of action. He filed a claim against Western with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario on the basis of discrimination, beginning a legal battle he says few students with disabilities have had the capacity to take on.

“There is a certain hesitation and fear of the system, and because of that, [students with disabilities] are afraid of standing up for their rights,” he says. “The university is taking advantage of [that fear] in the most cynical way possible.”

Alexander’s application for the tribunal was approved as of March 6, jumpstarting the often-lengthy process.

In the filing, he outlines a pattern of appeals, grievances and suggested remedies he’s submitted to the university over the year, recommending a series of changes to Western’s accommodation policy — the policy that cost him $2,400 tests and doctors notes to get accommodated. He writes in the filing that “nobody in the Science Faculty took the time to stop the pattern of discrimination. Had they done so, it would have prevented the snowball e ect of multiple discriminatory events, leading to a complete breakdown.”

None of the claims outlined in the filing have been tested in court.

While he knows the tribunal is a longshot, he hopes he can help move the needle in the right direction for the next generation.

“It's too late for me, I will not see the changes …. I want the students that come after to not experience what I've gone through.”

Lauren Jarman, USC vice-president internal a airs, holds accessibility close to her heart. She herself required a hearing aid accommodation during her undergraduate degree and says she knows what it's like to be her own advocate on top of being a full-time student.

“I think especially for students with disabilities, and people with disabilities in general, you just get tired of trying to legitimize yourself for others,” she says.

“We can't keep demanding students who are already struggling to keep doing their own self advocacy.”

She adds that the barrier of submitting documentation for accommodations is a hard one to overcome, both financially and personally.

“I think that's where the school probably finds some barriers is that they want to support students, but they also have to wait for that documentation to come through. And accessing that documentation is really, really challenging for students,” she says.

Pamela Block, a Western anthropology professor, a University of Western Ontario Faculty Association committee member and a disability researcher, added there are also complex barriers involved with providing accommodations as a professor.

She explains it is easy to lose sight of the burden certain accommodations can put on instructors, some of who are in need of their own accommodations.

“[Some professors] are taking care of elderly parents in the middle of COVID, or young children under five and some faculty members were looking after both,” she says. “It’s not that Western instructors are bad instructors, or are bad teachers or anything, it’s just that they don’t necessarily have that flexibility in their time and life.”

Block believes that, while technology is a barrier, sta ng shortages play a significant role in educational institutions’ ability to accommodate students with disabilities.

“If teachers had both the technology and the human supports they need, it would certainly be best for everyone,” Block says. “When administrations try to economize in ways that reduce the supports [that] teachers need to be successful — funding for TAs for example — then it ends up hurting everyone down the line.”

Western did not respond to a request for comment regarding Block’s concerns.

Jarman says, while she believes Western is in a position to commit more financial support to trained advisors, it's an issue of supply and demand rather than an unwillingness to put more people in those positions.

She explains there simply aren’t enough people in these jobs to help the number of students that need support. Jarman says, while she understands students' frustration, there are no easy solutions, given that many of the issues disabled students face on campus are microcosms of society.

“If a [student with a disability] goes o campus and still struggles finding those resources, that's where I think it's no longer just a Western issue,” Jarman explains. “That doesn't mean it's not something that the administration is willing to address, but it means that we're not alone in trying to find those resources.”

In spite of years of fighting for students like herself, Forrest says the school does not feel more accessible to her than it did a decade ago. She feels the system, in part, avoids change because those who are most vulnerable are scared they

will face backlash if they speak up.

“How can we address these problems if we’re not able to speak about them — and speak about them publicly in a way that the university can be held accountable?”

The lack of progress in removing some of campus’ most restricting barriers, including inaccessible washrooms, classrooms and study spaces, as well as sta ng shortages that have created an overwhelmed accommodation system, is at least in part a matter of financial priorities, according to Forrest.

Western recorded a record high $494.4 million in student fee revenue in the 2021-22 fiscal year. Forrest argues the school has a responsibility to those who pay tuition to reinvest a portion of that money to make the Western experience as accessible as possible.

“[Campus] is supposed to be designed for all students, but most people with disabilities who have mobility problems are excluded from those spaces,” she says. “There's money there but it's what the university chooses to prioritize with that money. And it's kind of frustrating for students with disabilities [because] we all pay tuition.”

Forrest says she won’t stop advocating for accessibility rights at Western, regardless of her past experiences with the school. Nearly two decades after she arrived on campus, her fight continues.

“I'm not going to be used as a token, I'm not going to be undervaluing myself anymore.”

NEWS | P5

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Jonathan Alexander on the second level of the McKellar Theatre in University College, Jan. 16, 2023

Tim Hortons Brier curling championship wraps up in London with Gushue win

SARAH WALLACE MANAGING EDITOR

In a packed Budweiser Gardens, Team Brad Gushue beat Team Matt Dunstone 7–5 to win the 2023 Tim Hortons Brier March 12. The championship marked Gushue’s fifth men’s curling national championship.

Gushue was the incumbent champion and played as Team Canada. His squad — consisting of lead Geo Walker, second E.J. Harnden and vice Mark Nichols — went 7–1 in the round-robin to place as the top seed in their division. This is the first time someone has won five Briers as a skip.

“What a finish. What a game,” Gushue said. “It’s definitely a team win [and] it’s easier when you’ve won a couple. You know you don’t need that for the legacy or for any personal reasons. At this point, it was about our team winning and that made it easier.”

The Brier and the Scotties Tournament of Hearts — the women’s national championship — are considered two of the most prestigious tournaments in curling. Eighteen teams from across the country compete to represent Canada at the World Championships.

Each province or territory has a playdown to determine their representative. Ontario is split into two — Northern Ontario and Ontario. There are also three Wildcard teams, who are teams who did not win their playdown, but have the most points in the Canadian Team Ranking System. The previous year’s champion plays as Team Canada, and does not participate in their region’s competition.

Over 6,500 fans watched the finals at Budweiser Gardens in downtown London, and more than 95,000 people attended the tournament since

its start on March 3. For most of the players, this is the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic they’ve played with a crowd this large.

“This crowd is phenomenal. From the opening draw on opening weekend, it was loud, it was busy. As players, this is all we can ask for,” said Harnden. “The atmosphere was unmatched and nothing I’ve been a part of for a long time.”

This is Team Gushue’s first year together with Harnden. Gushue, Walker and Nichols picked up Harnden out of Northern Ontario, who previously played second for Team Brad Jacobs. Sunday’s win is Harnden’s second national championship, and Walker and Nichols’ fifth.

“We couldn’t have asked for a better start to this run together. To win the Brier in the very first year is amazing,” said Harnden.

The stadium held fans of all ages from all across the country. The event had over 400 volunteers, some coming from as far as Halifax and Calgary. Director of sports tourism for Tourism London, Zanth Jarvis, said they had to close their volunteer application form early because they had “more than we needed.”

“It's a good testament to London and all of our community curling fans to help make sure this event goes well,” he said.

Volunteers hope the success of this event will give them a higher chance of hosting the Olympic curling trials for the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy.

The runners up, Team Dunstone, played as Manitoba. The teams went back and forth in the first half of the final, with both teams forcing the other to one point. The eighth end saw a mistake on Dunstone’s first, leaving Gushue a double to sit three. Dunstone responded in the ninth with a score of two, but Gushue was left with a draw to

Western swimming makes top 10 at championships

MANAN JOSHI SPORTS INTERN

Western’s swimming team finished their 2022-23 season on a high note, winning three medals and placing in the top 10 at the U Sports championships in Victoria, B.C. from Feb. 23 to 25.

Western University’s women’s team finished with 378 points to secure fifth place — their highest finish in nine years. The men’s team finished the event with 196.5 points to clinch 10th overall.

Highlights of the trip included second-year Shona Branton winning gold in the women’s 100-metre breaststroke and second-year Kieran Stone grabbing bronze in the men’s 200-metre freestyle.

Branton competed in the women’s 50-metre breaststroke on the first day of competition, where she picked up Western’s only medal of the day. She came in second with a time of 31.98 seconds. Danika Ethier from Laval University finished in first place, with Alicia L'Archeveque from the University of British Columbia finishing third, both standing next to Branton on the podium.

On day two, Branton, a Port Lambton, Ont. native, secured gold for Western with a time of 1:08.99 in the women’s 100-metre breaststroke. She swam past Ethier and UBC’s Eloise Allen to get on top.

“I was impressed with the double medals, but more importantly, with the quality of the performances,” said Western head coach Paul Midgley. “Shona moved up substantially in the world rankings with those swims.”

Stone made his mark in Vancouver by grabbing a bronze medal for the Mustangs in the men’s 200-metre freestyle.

The swimmer from Scarborough, Ont. had a time of 1:53.84, finishing just behind McGill University’s Pablo Collin and the University of Toronto’s Bernard Godolphin.

“Kieran [Stone]’s first medal at U Sports was an important milestone,” Midgley said. “I was impressed how he recovered from a rough first day to finish strong.”

The U Sports championships marked the end of the Mustangs 2022–23 campaign.

the four-foot to win the game in the 10th.

Gushue’s squad got the bye to the final after beating Team Dunstone in the 1v2 page playo 5–4 March 11. Dunstone had to make a hit in the 10th end, and rolled a few inches away to give the victory to Gushue.

Team Dunstone then played the semi-final March 12 against Team Bottcher, who played as Team Wild Card #1. Dunstone beat Bottcher 7–5 to secure a place in the final.

“The last 14, 15 hours have been really emotional, really di cult. But what more can you say, we made what we had to go down the stretch,” Dunstone said while tearing up after the semi-final. “Make eight [shots], anything can happen.”

With their win, Team Gushue will represent Team Canada and compete at the 2023 World Championships in Ottawa from April 1 to 9.

Frosh wins wrestling OUA, U Sports championships, Rookie of the Year award

EMILY GALUZZO SPORTS INTERN

EMILY GALUZZO SPORTS INTERN

Western Mustangs first-year wrestler Treye

Trotman finished o his rookie season by winning gold at the OUA and U Sports championships, and taking home both the OUA and U Sports male Rookie of the Year awards.

Trotman won the U Sports championship in Edmonton on Feb. 25. The first-year wrestler went 10–0 in the finals against the University of Alberta’s Talon Hird, taking the gold back home to Western University.

“I had more emotions when I won [at U Sports] than anything else,” said Trotman. “It was a pretty

big tournament. My one coach, Steven [Takashi], has won U Sports. It was good to follow in his footsteps and have him in my corner when I won.”

Trotman also went undefeated in the Ontario University Athletics championship in Hamilton, Ont. two weeks before on Feb. 11, finishing with an 11–0 win in the finals over McMaster University Marauders wrestler Francesco Fortino.

He was awarded the Keegan Trophy, marking the highest ranked male wrestler in the conference and OUA wrestling’s male Rookie of the Year.

Ten other Mustangs entered the U Sports championships alongside Trotman. Second-year Lukas Geske won gold, fourth-year Hassan Al-Hayawi won silver and second-year Patrick Salvador Guzman won bronze in their respective divisions.

SPORTS | P6

SARAH WALLACE GAZETTE Brad Gushue (right) with coach Caleb Flaxey and the Brier trophy, March 12, 2023.

COURTESY OF OUA Treye Trotman (top) wrestles an opponent on the mat.

COURTESY OF WESTERN MUSTANGS

From Western to TIFF: Cameron Bailey talks representation, diversity and love for movies

HANNAH ALPER OPINIONS EDITOR

Sitting in University College 36 years after graduating with an English literature degree, Cameron Bailey laughs as he remembers the time he and his friends made a poorly-produced film in the same building.

As the chief executive o cer and driving force behind the Toronto International Film Festival — one of the largest world-renowned film festivals — Cameron has elevated the organization to not only make it the equivalent of Cannes, but make it a place that equally celebrates film and the diversity of its audiences.

Cameron came back to his alma mater as this year's Duncanson Lecturer. The media mogul and alumnus spoke with students March 2 in University College, discussing the power of film. Cameron also had an “In Conversation With” March 3, where he spoke directly to students about his favourite films and the future of the industry.

Cameron credits his passion for film and the critical thinking skills learned at Western University for igniting his career at TIFF.

“When I came to Western and I took my first film course here, I learned that movies could do more than entertain and divert you from your life, but actually illuminate life,” he says. “They could be about ideas. They could be about political issues, social issues. I was interested in the world and curious about so many things that I wanted to see change in the world. Movies could help move those things forward."

Cameron explains that, on his drive to London, he couldn’t help but reflect on his experience as the first person in his family to go to university which, at times, was “an alien experience.” He describes himself as being “incredibly poor” as a student, on student loans and rarely having enough money for groceries.

“To come back in this role is very strange and

a little disorienting,” he says. “It reminds me that right now on campus, there are people going through what I went through. So I think about them and I hope they're going to be okay.”

Cameron says he found his people while working at CHRW FM — now known as Radio Western — and the Gazette for all four years of his undergraduate degree. He explains that he not only found his community, but gained countless skills that he connects to his role now as one of the most powerful people in the Canadian media industry.

Cameron used the skills learned in his time at the Gazette and CHRW FM to blossom in his career as a journalist and movie critic. He joined TIFF in 1990 as a seasonal programmer, then as artistic director.

His current job as CEO has him travelling the world for award shows, festivals and meetings, to meet with and find the next great story to tell. Cameron watches around 600 movies of the over 2,000 submitted every year. His role is to narrow it down to 200, which are then screened at the world-renowned festival.

Although TIFF 2022 held powerful moments, from Harry Styles walking the red carpet for My Policeman, to interviewing Taylor Swift for the All Too Well short film, Cameron says one of the greatest moments for him was the premiere of Black Ice. The documentary is about Black hockey players in Canada and the historic racism within the sport that still exists.

At the premiere of the documentary, Cameron invited some young Black minor league hockey players to see the film. He says for these players to see their own experiences being reflected on a giant screen in a 2,000-seat theatre made a huge di erence.

For Cameron, these are the moments that never get old.

Cameron hopes the films presented at TIFF will always present di erent identities and perspectives. He says the film industry has “com-

pletely changed” from expecting audiences to be invested in heroes that were almost exclusively white, straight, cisgendered men.

“Audiences are asking for more representation. Not because we want to fill out a checklist of different identities we see on screen, but because there's a particular power that comes from having your own experiences amplified and validated on screen,” he explains. “Some people have always had that [representation], where they never even had to think about it. It was taken for granted. It was assumed. And some people haven’t. So it does matter.”

As Cameron continues developing his passion for film through the festival, he reiterates that anyone has the power to tell real stories through

film. These movies are what make people feel things in a more unique way than seeing statistics or stories in the news.

“Wherever you are in your life and the world, you can make a positive change. We all have choices of what media we consume. Those choices allow us to expand our world to increase our empathy, open up some space for others who don't have that space provided to them already,” says Cameron.

“Whenever you have the opportunity, if you feel like there's some change in the world you want to see, and you have the opportunity not just to convince people intellectually, but to have them feel what you're feeling … that's major.”

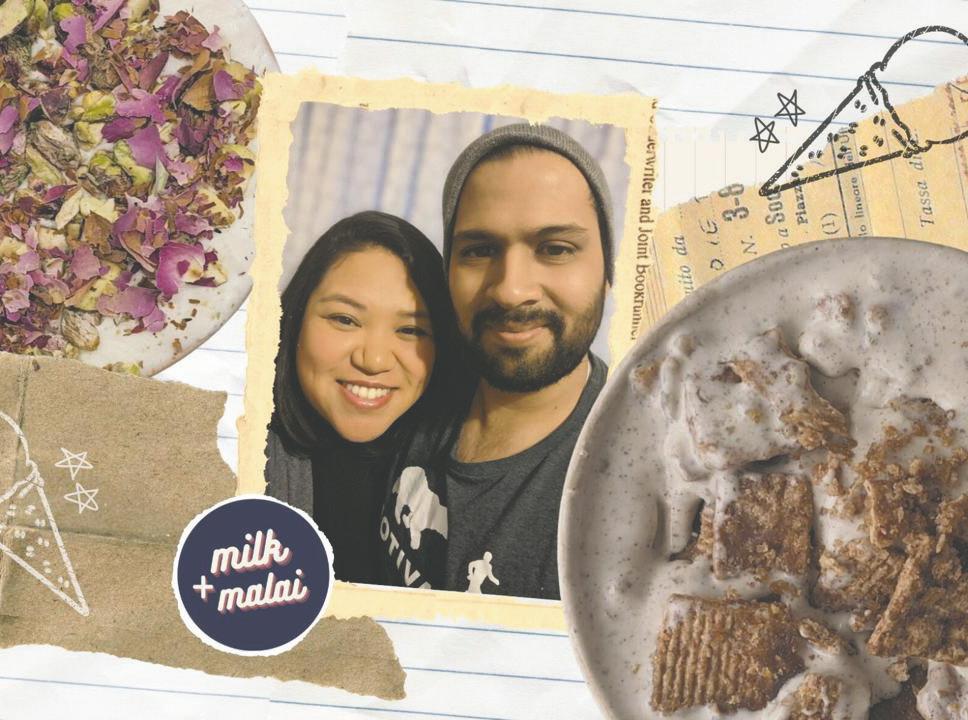

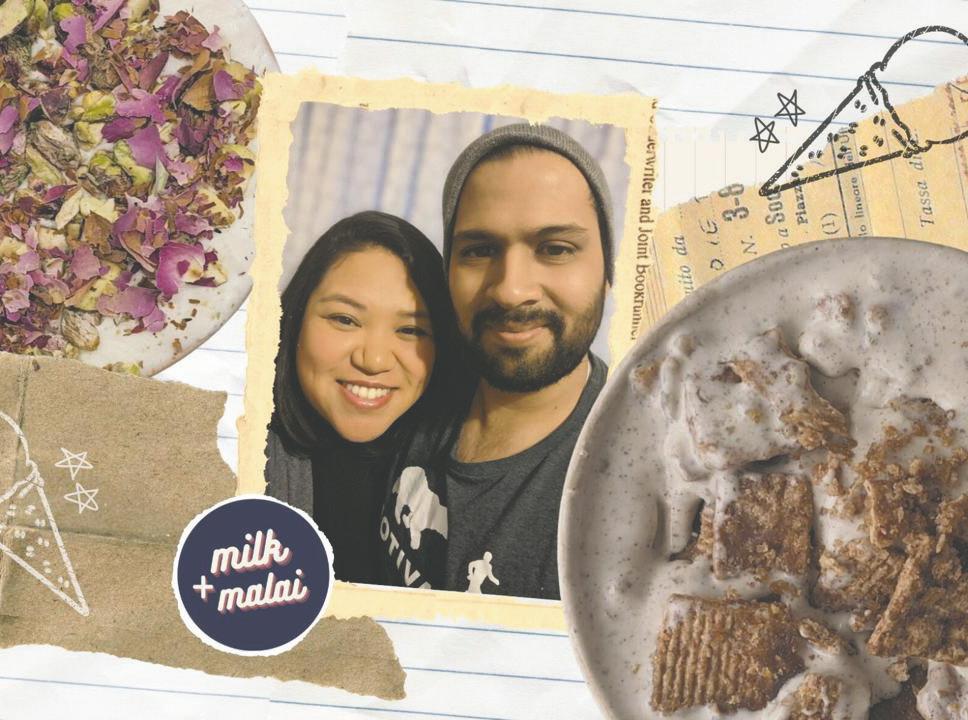

Forest City's ice cream love story: milk + malai

began selling their homemade creations commercially in the summer of 2022, starting at Komoka’s Community Market, a local farmers market.

While others were learning how to make bread during lockdown, Huzan Dordi was learning how to make ice cream.

Dordi, a London resident, first tried making mango ice cream to cheer up his partner, Awit Marcelino, at the height of lockdown. Three years later, the two have turned their hobby into milk + malai — a small batch ice cream business reimagining Filipino and Indian flavours.

Milk + malai is the only place on the block you can find combinations like ube and brownie crumble, pandan and pecan as well as sa ron and pistachio. The eclectic range of flavours is a combination of the two founders' cultural backgrounds.

“It’s unique because if we wanted to get ice cream at a regular shop, it wouldn’t really reflect our culture,” says Marcelino. “I think this can reflect some people’s cultures and childhoods in a way that brings a lot of joy.”

Dordi lived in India until he was 15 years old, and grew up with flavours like sa ron and pistachio. Meanwhile, Marcelino fondly recalls her Filipino-Canadian upbringing, watching her sisters and aunts make ube- and pandan-flavoured desserts.

“It’s a way for us to get to know more about each other’s childhoods,” says Marcelino, on reimagining ice cream flavours with her partner. “It’s like an ice cream love story.”

After running out of fridge space — and family to give away ice cream to — Dordi and Marcelino

Gratiana Chen, a fourth-year neuroscience student, first tried milk + malai’s sa ron pistachio ice cream at the Western Farmers Market last fall, and she’s been hooked ever since.

“I’ve never heard of ice cream [in] that flavour, which is kind of their whole concept,” says Chen. Milk + malai’s customer base is mostly made up of students. Marcelino and Dordi estimate approximately 80 to 90 per cent of their customers are from Western University.

“There’s a sense of familiarity or comfort at Western,” says Marcelino. “That’s what we loved at Western — it was fresh, people were game to try stu and for some people, it brought back memories.”

The business has no physical location. Dordi and Marcelino make their ice cream out of a certified commercial rental kitchen, where oftentimes the only slots available to book are between 4 a.m. to 8 a.m.. They then personally deliver online orders, sometimes as a makeshift date night or on their way to get groceries.

Outside of the business, the couple still works their full-time jobs — Dordi as a high school teacher and Marcelino as a pastor.

In the future, they hope to further expand their range of flavours.

“We always want to be creating ice cream that tells a story,” says Marcelino. “I want to enjoy the flavours I grew up with and I want other people to have that opportunity.”

Experimenting with flavours is a trial-and-error process for Dordi and Marcelino. But one thing always stays the same: Marcelino is the first taste-tester for any new flavour they create.

“At the end of the day, it’s milk, sugar and cream,” says Dordi. “What sets us apart are our flavours and our stories.”

CULTURE | P7

SOPHIE BOUQUILLON GAZETTE Cameron Bailey in Conron Hall, March 3, 2023.

MONIQUE FLEMING GAZETTE

TANG

CAT

CULTURE EDITOR

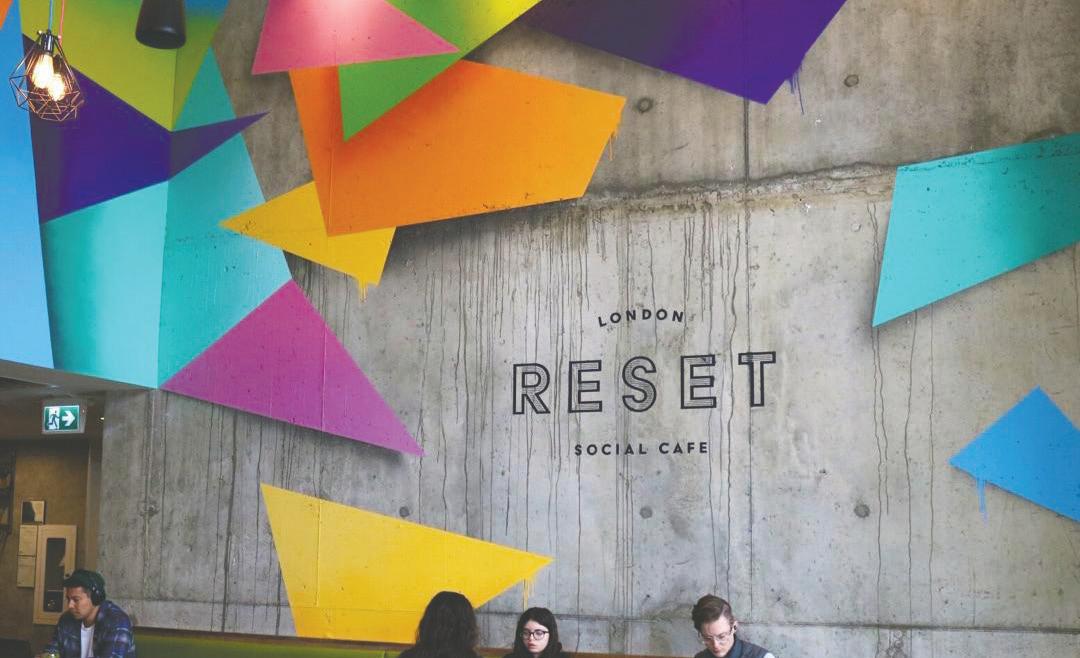

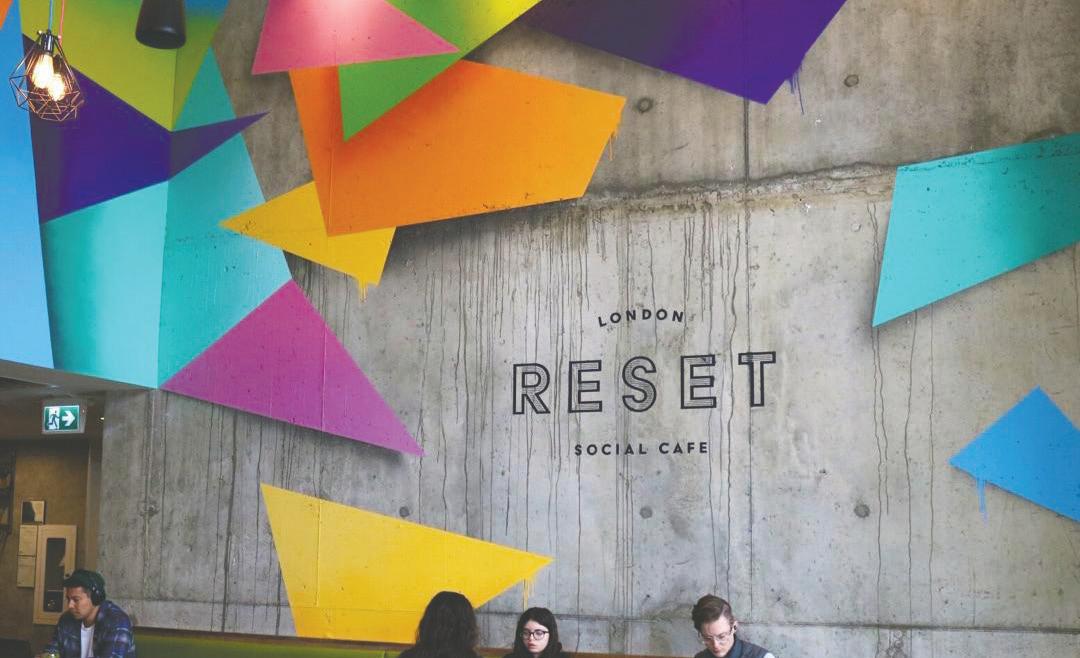

Cafe hopping: The Reset Social Cafe

LAUREN MEDEIROS CULTURE EDITOR

ResetSocial Cafe is buzzing with energy, even at 10 a.m. on a Friday — it’s only been open for three hours and every table is full.

When I walk in from the Talbot Street entrance, I’m greeted by the brightly coloured, geometric paintwork on the cafe’s stone walls before a barista can even say “hello.”

Reset has an overwhelming amount of beverage choices. There are six di erent smoothie choices, four juices and about 20 ca einated drinks, served either hot or cold. These options can be made with any flavoured syrup and milk option imaginable.

Adam Grinstead, owner of Reset, says the cafe prepares as much of its food as possible from scratch. Their dressings, sauces and eggs that accompany their wraps, sandwiches, salads and bowls are prepared behind the counter fresh everyday — even all of the co ee is roasted on-location.

“I think our food is a big part of what sets us apart … I never wanted the food at the cafe to be an after-thought,” says Grinstead. “This extra care and desire to make every guest feel valued is a key component of what makes us unique.”

Out of all the cafes I’ve tried throughout my cafe reviews, Reset’s menu is certainly the largest and most impressive.

I start my morning o with a juice called “Self Pear,” made with cucumber, pineapple, kale, lemon and the titular pear. I also order an iced matcha latte with oat milk to test out their long list of ca eine options. I’m pleasantly surprised when I discover they don’t charge extra for the milk alternative like they do at most cafes. It’s nice to know Reset supports my sensitive stomach’s needs.

The matcha is nothing extraordinary, but the juice is delicious and unlike anything I’ve had before — it’s light, refreshing and cucumber-forward. This said, it’s not something I’d be willing to

pay $6.75 for on a regular basis — I consider it a nice treat after a long week of midterms.

Monica Paynter, one of Reset’s baristas, says the cafe delivers more than fresh food and drinks.

“It’s a place to come and relax, but also to be motivated to get things done,” says Paynter. “That’s what [Grinstead’s] goal was — to reset, relax and recharge.”

During the day, the crowd is mostly people with laptops and headphones, but in the evenings — the cafe is open until 8 p.m. — it’s filled with people socializing, some even adding a shot of kahlua or vodka to their co ee.

The colourful cafe attracts a lot of students, according to Paynter, since there is no seating time

limit. There are students, especially throughout finals season, who frequent the cafe and sometimes spend the whole day on their comfortable benches.

“We’ll never kick you out,” says Paynter. “A lot of students, I now know personally by name, and their order. It feels like we’re friends, they’re not customers.”

Reset Social Cafe is true to its name — a place where people feel connected in sharing a lively, bright and happy space.

Opinion: Science class needs to change for ChatGPT

— and the advent of ChatGPT shows AI’s ability to express that knowledge conversationally and apply it in new contexts.

plenty of ways to fulfil the oft-dreaded Category B without doing much thinking at all.

well as my classmates.

SONIA PERSAUD NEWS EDITOR

SONIA PERSAUD NEWS EDITOR

Whenthey invented the handheld calculator, I bet people probably felt the same way.

I’m not the first to say that, since its release in December 2022, ChatGPT has taken the world by storm. It’s passed Google’s software engineering coding interview — for a job with an average compensation of $183,000 United States dollars — and even the United States medical licensing exam.

It’s spurred questions of whether it’s ethical for a computer to do your homework or help you with an essay. I’m not here to argue that — I think the question of what it means for our education is more interesting.

While it’s not perfect right now, it’s fair to say AI might one day surpass human technical ability. Simply put, an individual human’s semantic knowledge can’t compare to that of a computer

But will it fully replace humans in science roles? PCMag asked this question to ChatGPT itself. The AI responded it can’t completely replace a human’s “creativity, problem-solving skills and critical thinking abilities.”

If that’s what sets us apart from AI, then that’s what our programs need to be teaching. But right now, that’s not how Western University’s science programs are designed — at least not in my experience.

In first- and second-year medical sciences, we’re mostly tested on our knowledge through multiple-choice exams. Even the essays feel rote and memory-based, in a way — if you stick to a prescribed formula of information to include, you’ll probably get close to full marks.

By third year, my exams might finally end in short-answer questions, but usually all they ask is for me to rattle o information I’ve memorized.

At Western, breadth requirements ensure every science graduate walks out with 1.0 arts and humanities or languages credit, but there are

If a Science student takes Classics 1000 — a course with exclusively multiple-choice tests — they can learn by rote the same way they can for Biology 1001. And while this might expand their worldview, it won’t expand their ability to critically think about science or anything else for that matter.

Making students take an English or media class isn’t the solution here. Instead, I hope that ChatGPT demonstrates to university science educators the importance of engaging their students’ critical thinking skills and creativity — and integrating it accordingly.

I appreciate the work many of my professors have already put in to encourage critical thinking in their courses — turning a pharmacology lecture slot into a case study and discussion, for example. One of my neuroscience courses takes this to the extreme with students leading class discussions on scientific papers.

We need more of this approach. If I ask ChatGPT to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of a neuroscience paper, it doesn’t do nearly as

As well, Western science graduates — whether they’re computer scientists serving as AI designers, or chemists using AI in their research — need to understand the social, cultural and ethical implications of these emerging technologies. Social responsibility, in other words, is a crucial skill all science graduates should have. We’re not teaching it as well as we could, but we certainly need to be.

Like a handheld calculator, ChatGPT is a tool that makes work easier — can you imagine doing long division in university? Like a calculator, AI can help us do basic work more easily, freeing up our time for the interesting stu .

So the “interesting stu ” — problem-solving, inquiry and social responsibility — is a crucial part of what we need to be learning in university because frankly, it’s one of the only advantages we have over AI.

With every leap forward in technology, education has needed to change to catch up. ChatGPT is the latest. I hope it can demonstrate something I think has been a long time coming — the importance of emphasizing inquiry, problem-solving and application in science education.

CULTURE / OPINIONS | P8

apit @UWOGAZETTE @WESTERNGAZETTE / WESTERNGAZETTE /UWOGAZETTE / WESTERNGAZETTE @UWOGAZETTE

LAUREN MEDEIROS GAZETTE

The brightly coloured, geometric paintwork on Reset's stone walls, March 3, 2023.

LAUREN MEDEIROS GAZETTE Monica Paynter, one of the baristas at Reset, March 3, 2023.

LAUREN MEDEIROS GAZETTE Matcha and juice from Reset, March 3, 2023.

EMILY GALUZZO SPORTS INTERN

EMILY GALUZZO SPORTS INTERN

SONIA PERSAUD NEWS EDITOR

SONIA PERSAUD NEWS EDITOR