VOLUME 4 | ISSUE 1 WINTER 2023

STUPENDOUS SUPERNATURALISM KUYPER’S CAUTION PLUS: A MATTER OF INTEGRITY

MACHEN ON EDUCATION HOW WORDS MATTER WESTMINSTER NEWS & UPDATES TELLING THE TRUE GOSPEL IN THIS ISSUE: J. Gresham Machen’s Classic Book and a Century of Influence

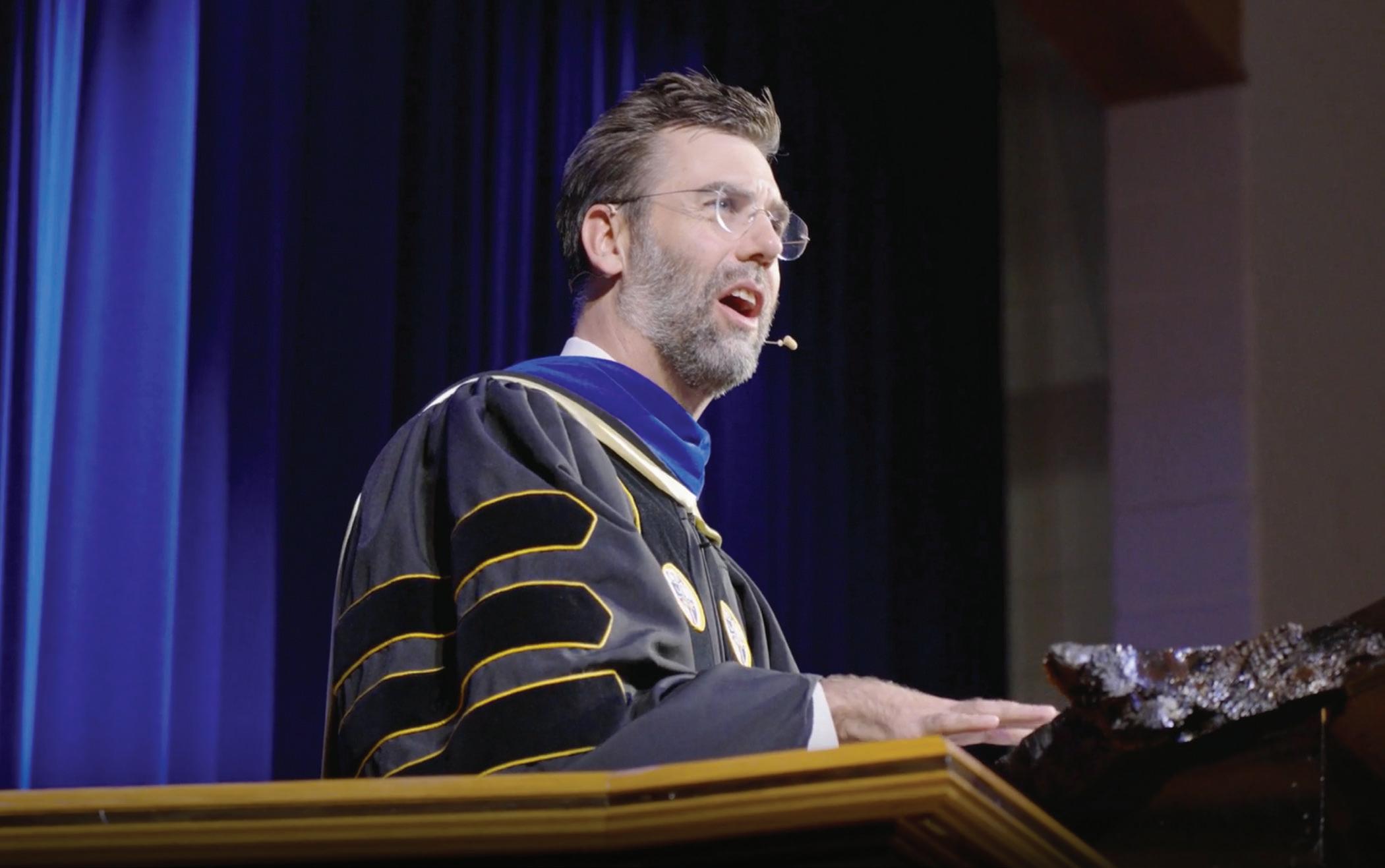

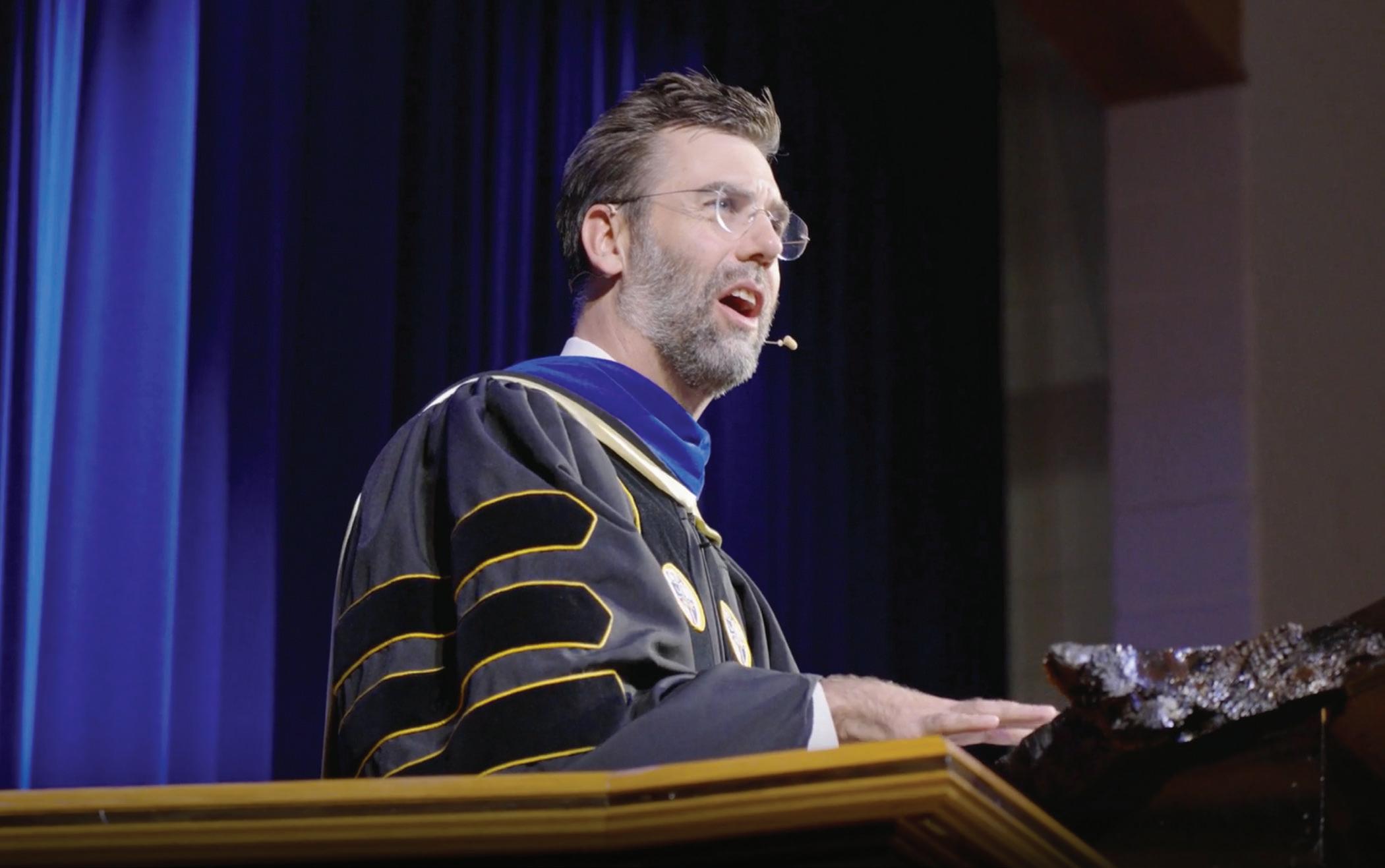

Peter A. Lillback

William R. Edwards

Mark A. Garcia

Shao Kai Tseng

“The things that are sometimes thought to be the hardest to defend are also the things most worth defending.”

J.Gresham Machen

FROM THE PRESIDENT I

t is always a privilege to share the new issue of Westminster Magazine with you! We are grateful for the encouragement that this lovely communication has been for so many. We are blessed in sending it and in receiving it ourselves. We are thankful, too, that many are finding new depths of spiritual encouragement as their knowledge of Scripture grows through its articles, and even the artwork.

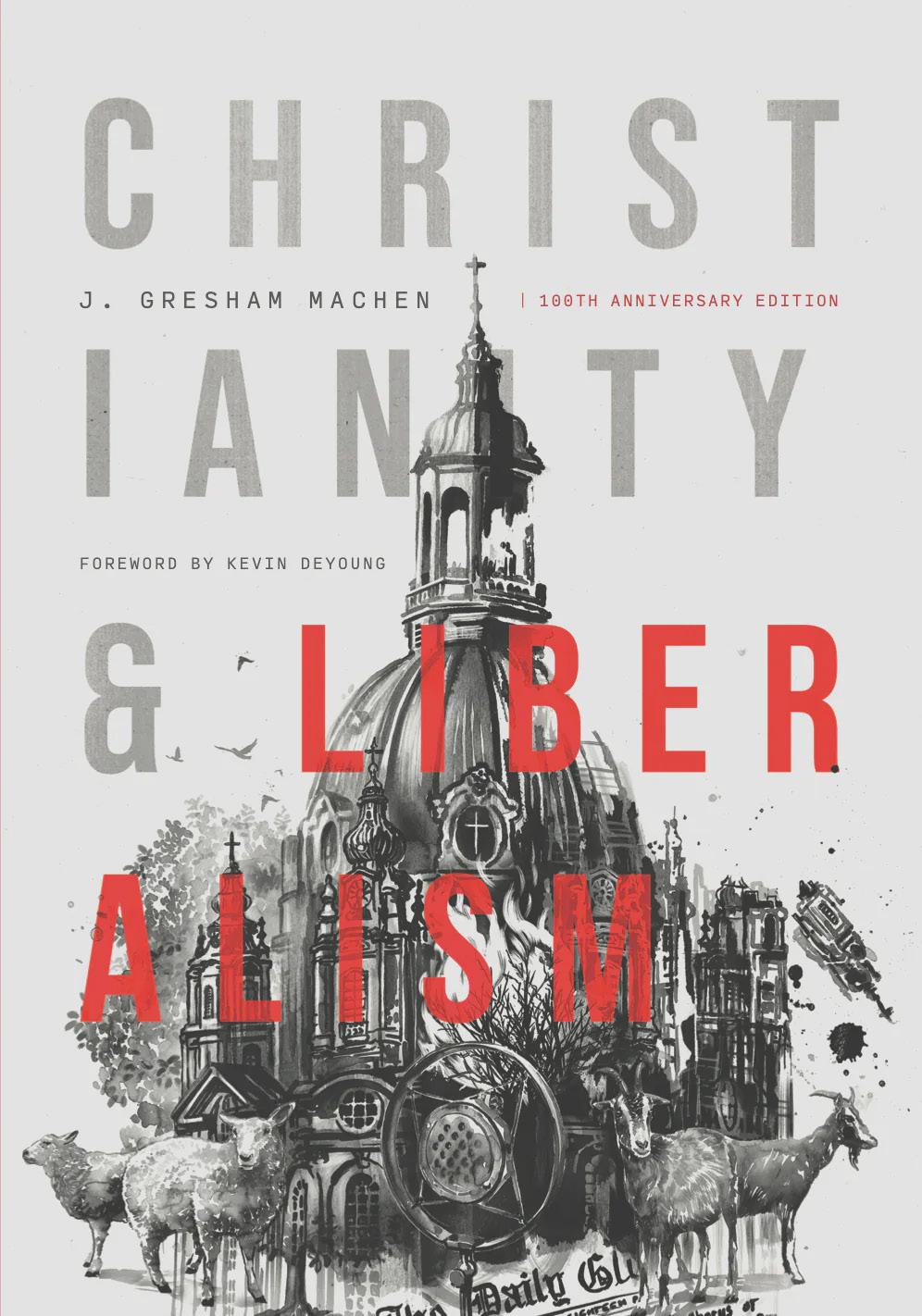

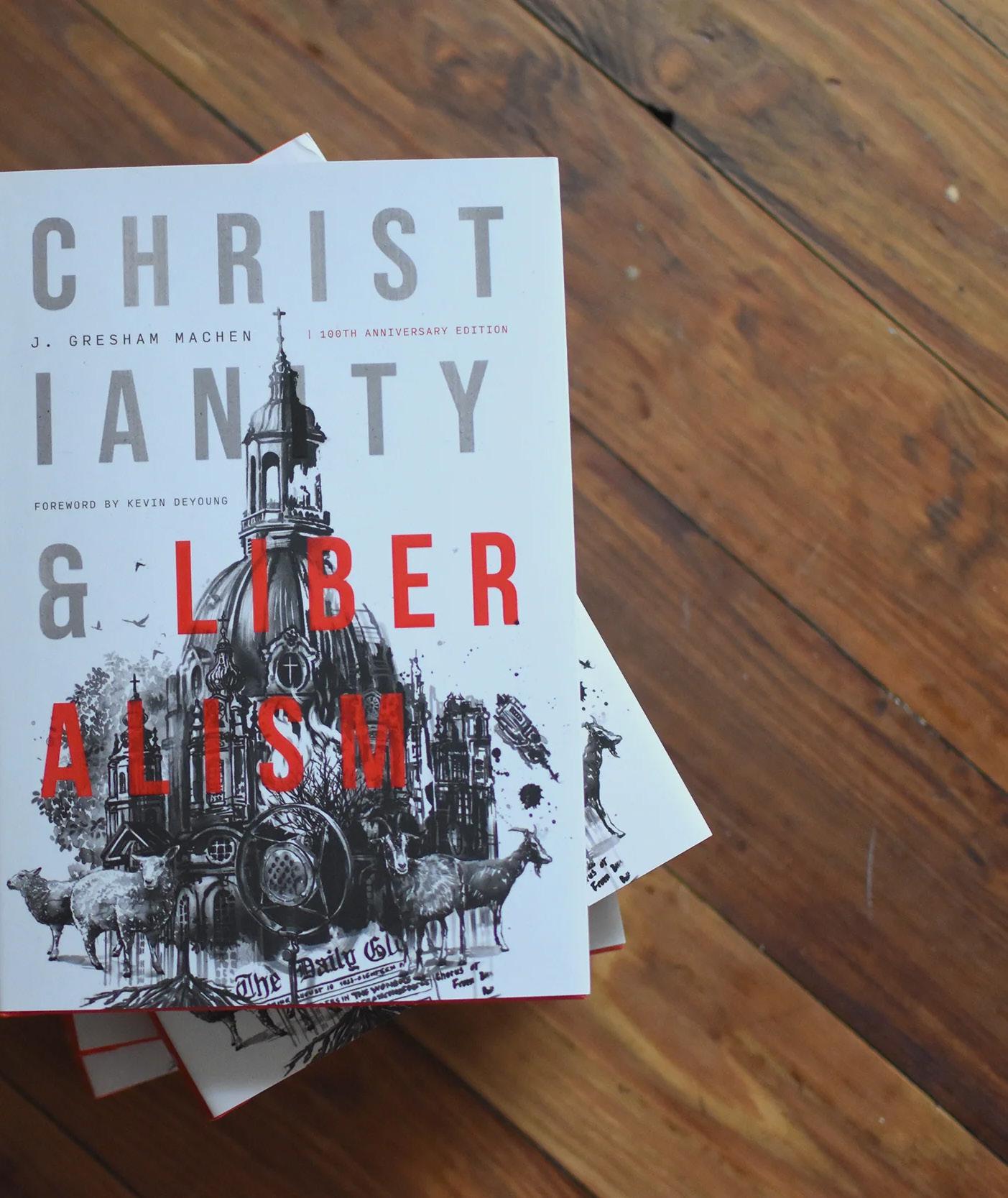

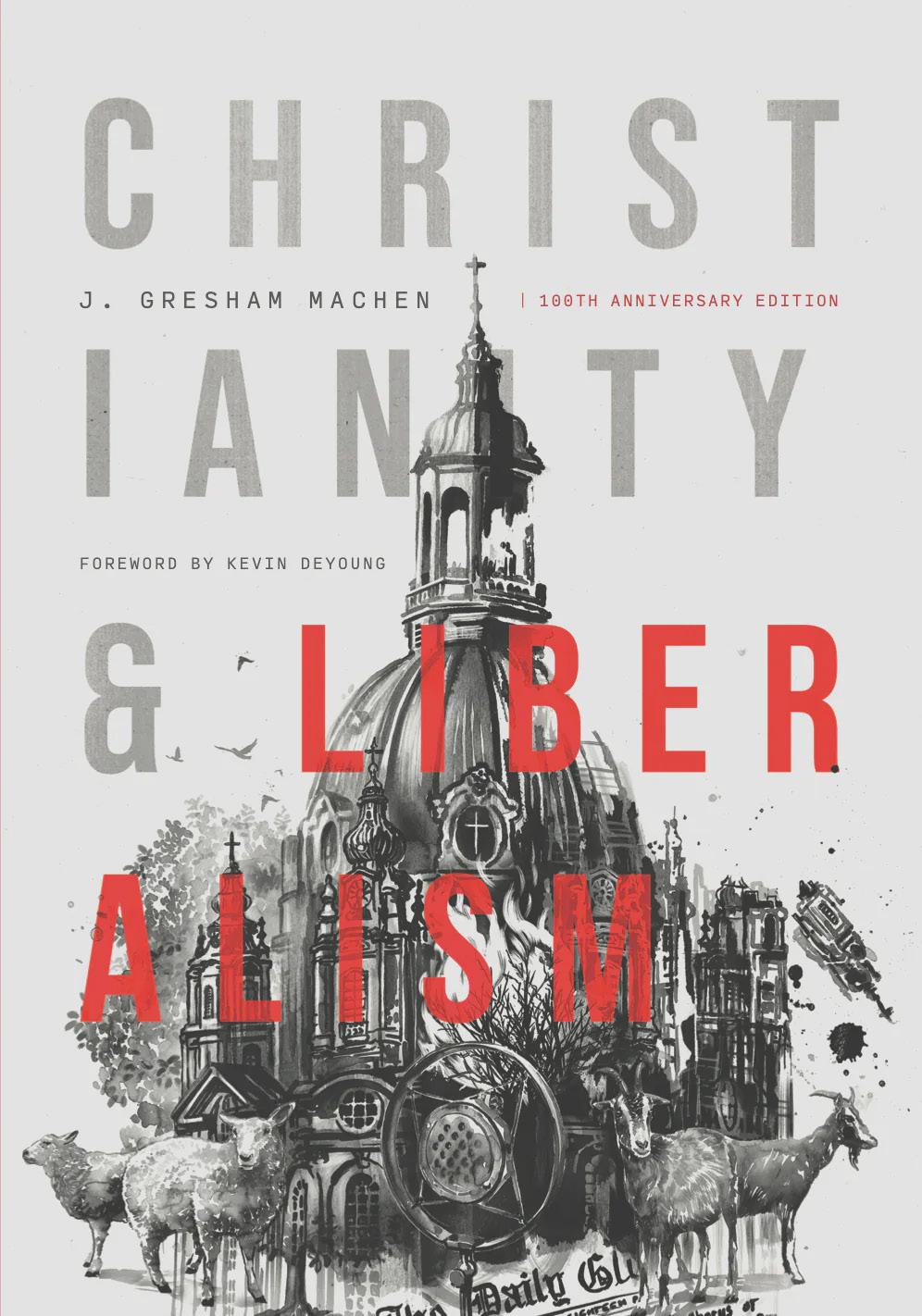

In this issue, we reflect on J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism and its theological legacy, and we remember how effective his book was in spreading the message of the historic Christian faith. It has not gone out of print since it first appeared and has even gone through various editions here at Westminster.

Most especially, we are thankful for the global impact that Machen’s message has had. The book has been translated into languages around the world and continues to be read as though it were written for us today.

This global, gospel-spreading role of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism is complemented by the global, gospel-spreading role of Machen’s Westminster. Indeed, our seminary exists in order to train specialists in the Bible to proclaim the whole counsel of God for Christ and his global Church. We pray that you will be drawn closer to the Lord Jesus Christ through Westminster’s message—a message that will never go out of date.

At this centennial of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism, we are grateful for your partnership in proclaiming the matchless grace of Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of God, whose supernatural Christianity is ever true and vital unto the salvation of souls.

Your brother in Christ’s service,

Peter A. Lillback, President

Peter A. Lillback, President

Volume 4 | Issue 1 | Fall 2023

Editor–in–Chief

Peter A. Lillback

Executive Editor

Jerry Timmis

Editor

Josh Currie

Managing Editor

Nathan Nocchi

Associate Editor

Pierce Taylor Hibbs

Contributing Editors

B. McLean Smith

Anna Sylvestre

Design

Ethan Greb

Interior

Angela Messinger

Additional Design

Kira Millick

Read, watch, and listen at wm.wts.edu.

WestminsterMagazineaccepts pitches and submissions of previously unpublished work. For more information, email wtsmag@wts.edu.

WestminsterMagazineis published twice annually by Westminster Theological Seminary, 2960 Church Road, Glenside, Pennsylvania 19038. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations.

Printed and bound in the United States of America

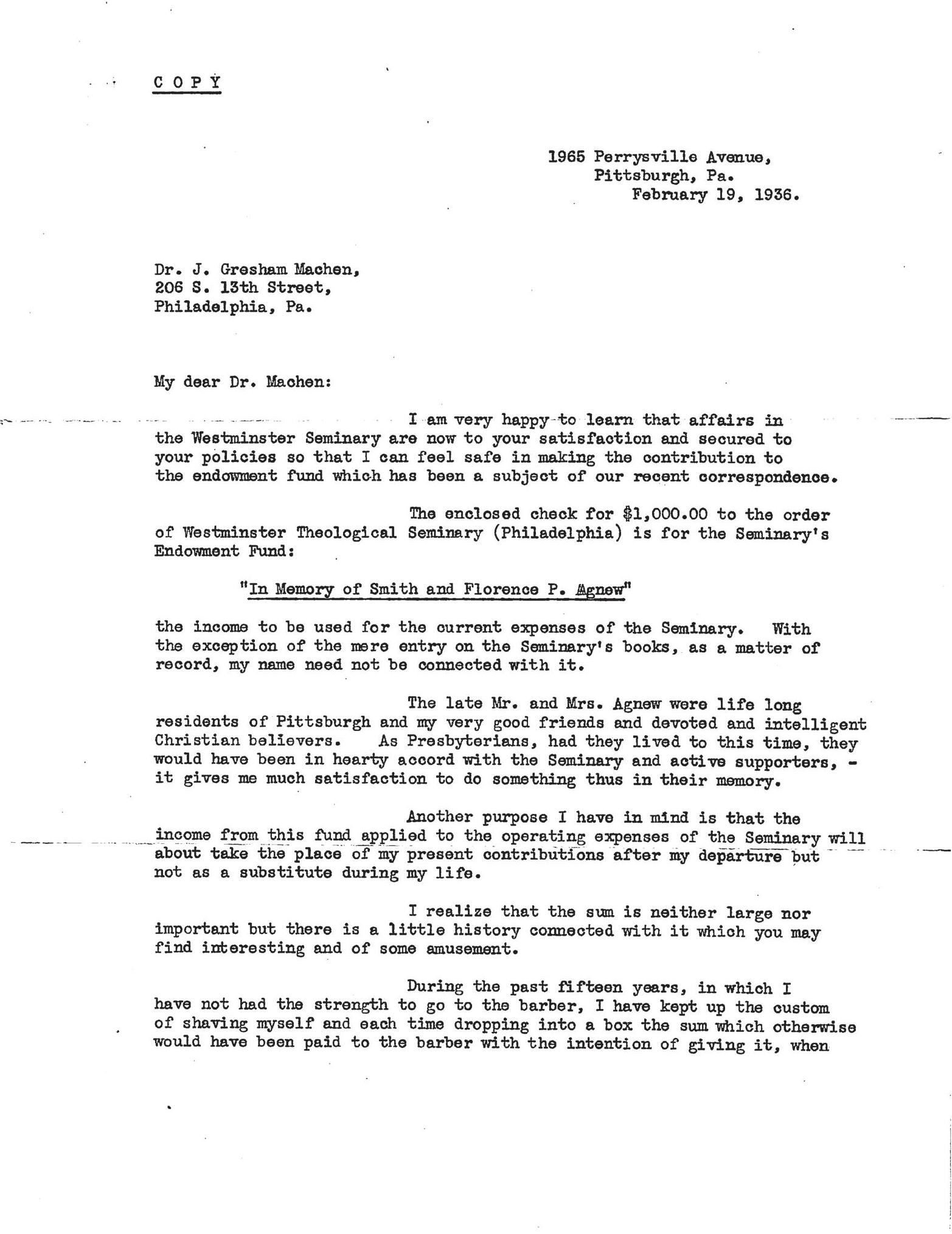

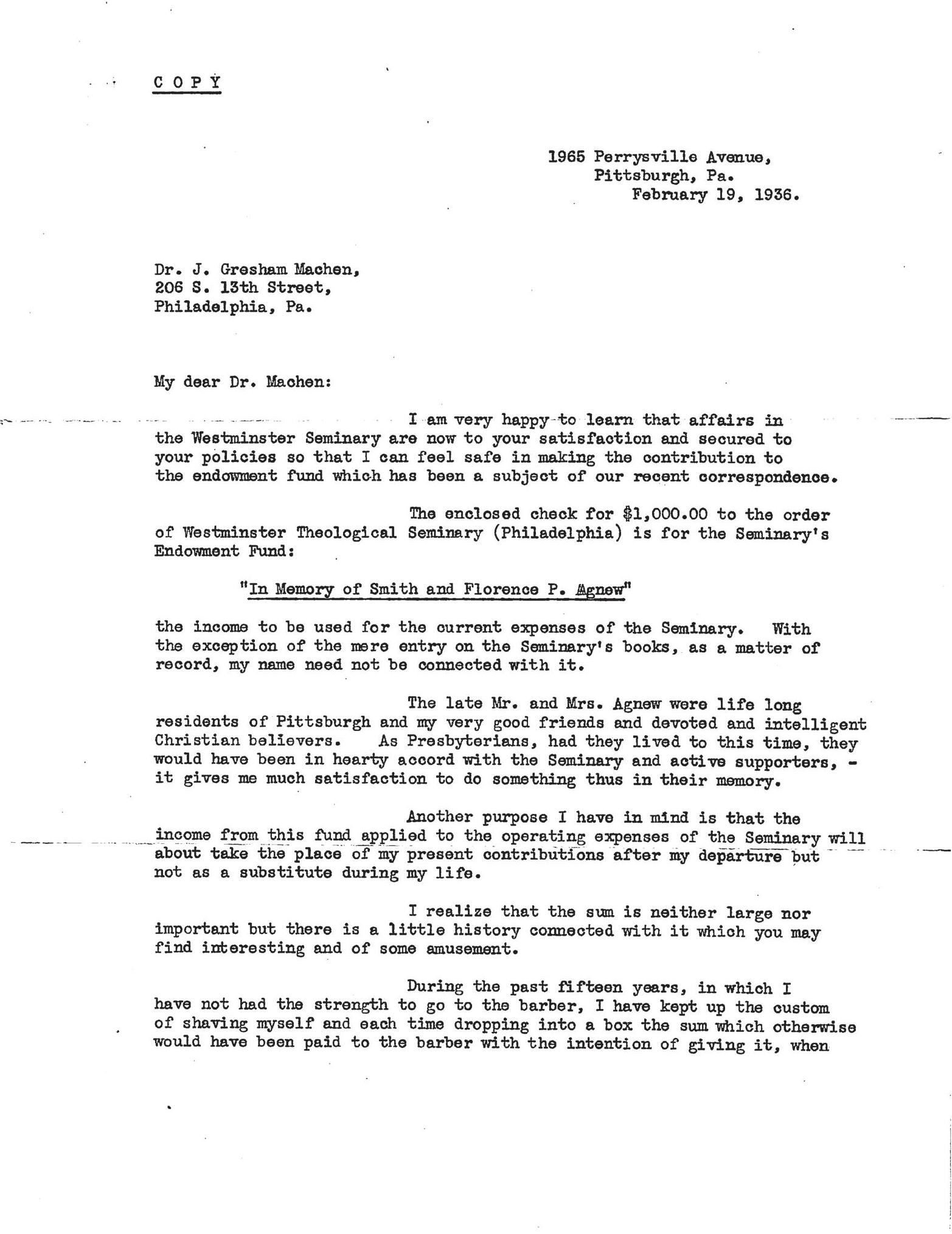

Handwriting samples featured in this issue are from J. Gresham Machen's manuscript draft of Christianity and Liberalism.

GAZINE

WESTMINSTER MA

The Jan H. Jacks Hospitality Garden (photo: Abram Hammer)

The Jan H. Jacks Hospitality Garden (photo: Abram Hammer)

FALL 2023 Westminster News and Events .............................. 32 Faculty News and Updates ................................. 34 Faculty Profile: Stephen M. Coleman ......................... 38 From the Archive: Senate Testimony | J. Gresham Machen ........ 42 True Learning and True Piety | J. S. S. Patterson .............. 48 Student Spotlight: Andrew Becham 54 For the Church | Rich S. Brown III ......................... 58 How Words Matter | Pierce Taylor Hibbs..................... 64 Alumni Profile: Rob Golding ............................... 70 Point of Contact: Claim Your Creed | Peter A. Lillback .......... 74 Closing Liturgy: A Prayer for the Morning | Daniel Featley ....... 76 STUPENDOUS SUPERNATURALISM Peter A. Lillback A MATTER OF INTEGRITY Mark A. Garcia TELLING THE TRUE GOSPEL Shao Kai Tseng KUYPER’S CAUTION William R. Edwards 4 1 8 12 2 4

STUPENDOUS SUPERNATURALISM:

The Century-old Gospel Heart of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism

Peter A. Lillback

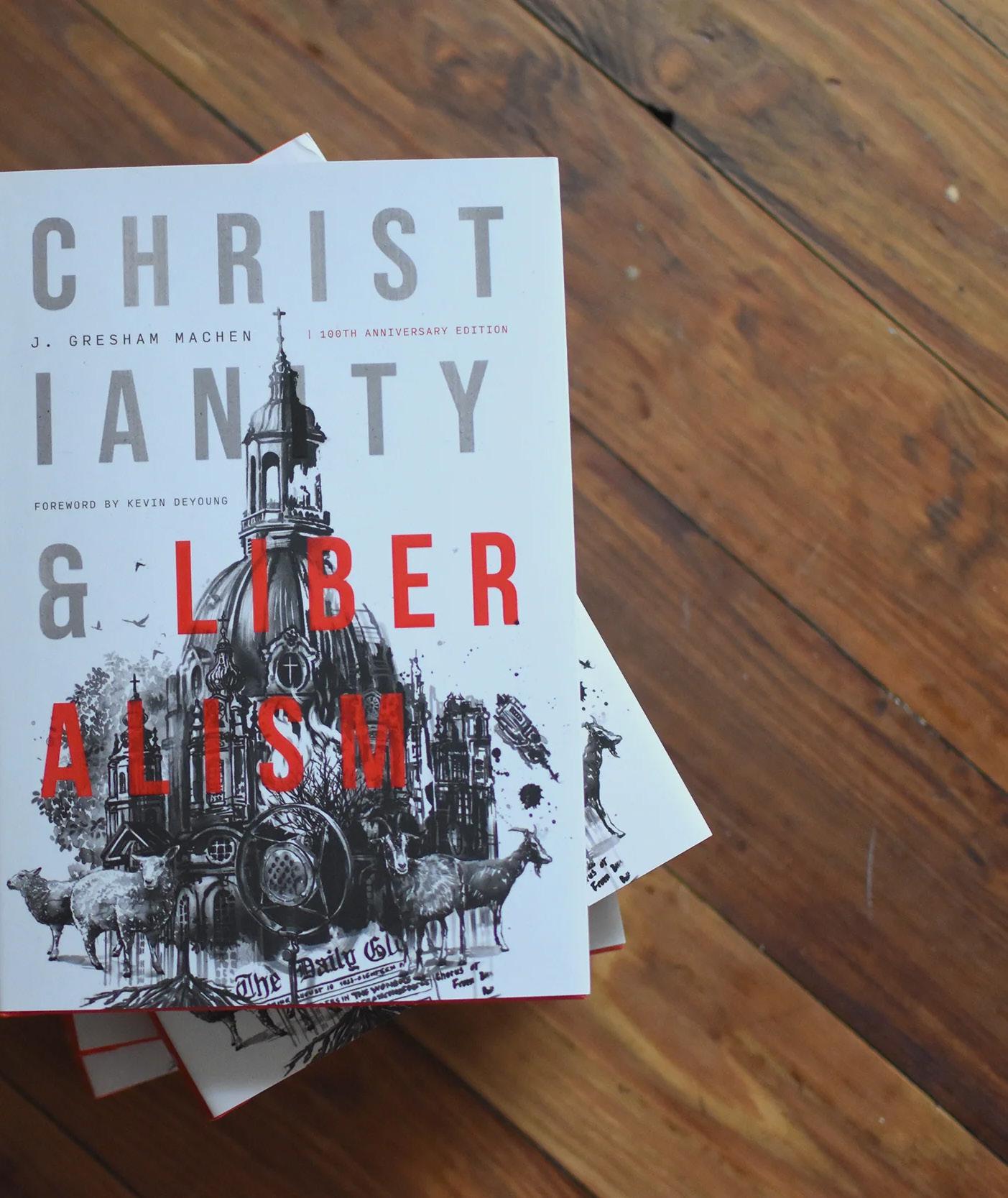

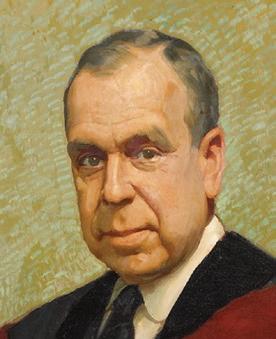

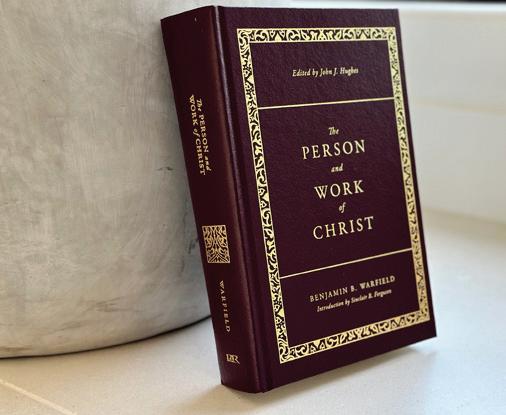

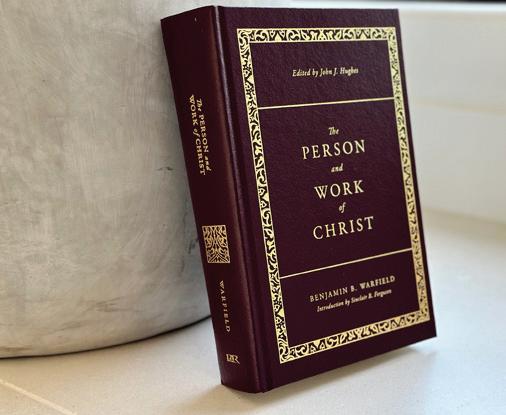

If you haven’t heard, 2023 marks the centennial of the publication of J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism, a book that George Marsden described as “one of the most important religious works of the twentieth century,” and one that is dear to the heart of our seminary. Through our publishing arm, Westminster Seminary Press, we’re celebrating this milestone with a new edition of Machen’s seminal treatise, a companion podcast series, a new audiobook recording, and a study guide. But there is always more to the story of Christianity and Liberalism that we can tell. That’s because its story continues to grow each year! Throughout the century of its existence, Machen’s book has remained in print through multiple editions and publishers. And it continues to be translated into increasingly more languages around the globe each year. Without a doubt,

this is a special book, the significance of which is well worth exploring.

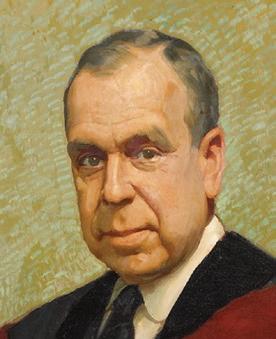

A Brief History

When Machen’s critique of liberal protestant theology appeared in 1923, it launched him on a tempestuous journey that carried the then Princeton Seminary professor to international prominence. Machen’s decisive popular preaching and trenchant scholarly publications manifested his deep theological commitment to confessional Presbyterianism, and he became the leading scholarly voice of biblical Christianity in its confrontation with the liberalizing theology of Presbyterianism and other main line protestant denominations. After the reorganization

4 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

Ippolito Caffi, Eclisse di sole alle Fondamenta Nove (1842)

of Princeton Seminary in 1929, which solidified that institution’s embrace of theological Liberalism, Machen’s historic Reformed theological commitments providentially led to the founding of Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. And the ongoing ecclesiastical controversies in Presbyterianism eventually compelled him in 1936 to organize a new denomination that became the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. After Machen’s death on January 1, 1937, Princetonian Caspar Wistar Hodge described him as, “the greatest theologian in the English-speaking world” and “the greatest leader of the whole cause of evangelical Christianity” (Ned B. Stonehouse, J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Memoir, 7). Machen’s pivotal role in the defense of historic Christianity continues to be recognized today. The accomplished endorsers of Westminster Seminary

Press’s new edition of Christianity and Liberalism confer remarkable accolades upon the author and his historic book (p. i–vii.). They speak of Machen’s “courage,” his “important” work, and “classic defense” of historic Christianity. They note that Machen’s “prescience” was adorned by “precision,” “logic,” and “clarity” that characterized his “prophetic” message. Indeed, this “little book,” as Machen described it (9), is assessed by one endorser as “prescient in its time and … even more relevant in ours.”

So, it stands to reason that Machen’s view of Liberalism is worth exploring, along with the vital significance of his distinction between theological Liberalism and Christianity proper. I believe that more than a little precious insight can be gained by taking a closer look at Machen’s articulation of “stupendous” aspects of supernatural Christianity.

Liberalism’s Naturalism Is Inherently Opposed to Biblical Christianity

Machen argued that although Christianity and Liberalism used the same terms, they were, in fact, two different religions. He explains,

In the sphere of religion, in particular, the present time is a time of conflict; the great redemptive religion which has always been known as Christianity is battling against a totally diverse type of religious belief, which is only the more destructive of the Christian faith because it makes use of traditional Christian terminology. This modern non-redemptive religion is called ‘modernism’ or ‘liberalism’ . . . . the root of the movement is one; the many varieties of modern liberal religion are rooted in naturalism—that is, in the denial of any entrance of the creative power of God . . . in connection with the origin of Christianity (2).

The chief modern rival of Christianity is ‘liberalism.’ An examination of the teachings of liberalism in comparison with those of Christianity will show that at every point the two movements are in direct opposition (53).

For Machen then, Christianity is the revealed religion of the Lord Jesus Christ while the Christianity of liberal theology was a reduction of the former into a sort of

Fall 2023 | 5

pre-Christian religion resulting from Liberalism’s efforts to reconcile Christianity with naturalistic philosophy and science (see p. 7).

In fact, Machen argues that there is no ultimate conflict between historic Christianity and science itself so long as Christians maintain a proper understanding of God’s role in creation and providence (102–103). Ironically, it is liberal theology that is at odds with science: “. . . it is not the Christianity of the New Testament which is in conflict with science, but the supposed Christianity of the modern liberal church, and that the real city of God, and that city alone, has defenses which are capable of warding off the assaults of modern unbelief” (7).

The real motive behind modern Liberalism, Machen argued, was to accommodate religion to those who had rejected the supernaturalism of biblical Christianity in favor of the naturalistic tenets of unbelieving science. But the result was not Christianity; it was a new manmade religion marked by deistic or pantheistic perspectives emanating from enlightenment era philosophy (102–105). “Naturalistic liberalism,” Machen insists, “is not Christianity at all” (52).

Naturalistic liberal religion, according to Machen, begins its method of resistance to historic Christianity by rejecting the importance of the church’s creeds and doctrines. When it comes to doctrine, the liberal sees creeds as “merely the changing expression of a unitary Christian experience and provided only they express that experience they are all equally good” (18).

“At the outset,” Machen explains, “we are met with an objection. ‘Teachings,’ it is said, ‘are unimportant; the exposition of the teachings of liberalism and the teachings of Christianity, therefore, can arouse no interest at the present day; . . . The teachings of liberalism, therefore, might be as far removed as possible from the teachings of historic Christianity; and yet the two might be at bottom one” (18).

But, as Machen points out, “If all creeds are equally true, then since they are contradictory to one another, they are all equally false, or at least equally uncertain. . . . Very different is the Christian conception of a creed. According to the Christian conception, a creed is not a mere expression of Christian experience; on the contrary, it is a setting forth of those facts upon which experience is based” (19).

This leads to Machen’s perspective that what is really at the heart of the disagreement between Christianity

and modern liberal naturalistic theology is their differing attitude toward the supernatural.

Naturalistic Liberalism Rejects Christianity’s Supernaturalism

It is indicative that much of Machen’s burden to expose the profound differences between the two religions of Christianity and Liberalism rests on repeatedly contrasting the supernatural character of historic biblical Christianity with the liberal’s rejection of anything suggesting the supernatural. He insists that “supernaturalism . . . is the very thing that the modern reconstruction of Christianity is most anxious to avoid” (91). “. . . Christians . . . have accepted as true the message upon which Christianity depends. A great gulf separates them from those who reject the supernatural act of God with which Christianity stands or falls” (77). “That belief [in the resurrection of Jesus] involves the acceptance of the supernatural; and the acceptance of the supernatural is thus the very heart and soul of the religion that we possess” (112). Similarly for Machen, the new birth experienced by the Christian as depicted in Galatians 2:20 reflects “the supernaturalism of Christian experience” (143).

The liberal’s rejection of the supernatural is so decisively non-Christian, Machen argues, that the Jesus of liberal Christianity is no longer supernatural. “. . . liberalism regards Jesus as the fairest flower of humanity; Christianity regards Him as a supernatural person” (97). “. . . the Jesus presented in the New Testament was a supernatural Person. Yet for modern liberalism a supernatural person is never historical. . . . He is supernatural, and yet what is supernatural, on the liberal hypothesis, can never be historical. The problem could be solved only by the separation of the natural from the supernatural in the New Testament account of Jesus in order that what is supernatural might be rejected and what is natural might be retained” (110).

Naturalistic Liberalism Rejects Doctrine That Flows from Supernaturalism

What is true for the liberal’s view of Christ— the rejection of his supernatural character—is true also for the liberal’s view of doctrine. Liberalism’s rejection of the supernatural

6 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

inevitably shapes how they view God and man, the Bible, salvation, and the church as there is an intrinsic logic that controls naturalistic liberalism as a system of thought (177).

Accordingly, the liberal claims, “theology, or the knowledge of God, . . . is the death of religion; we should not seek to know God, but should merely feel His presence” (55). Against bare pantheistic religious experience (64), however, “. . . Christianity is the belief in the real existence of a personal God” (59). This stands in stark contrast to the liberal’s vague claim of “the universal fatherhood of God.” Moreover, “the universal fatherhood of God is not to be found in the teaching of Jesus” (61). Rather, “The God whom the Christian worships is a God of truth” (77). “Rational theism, the knowledge of one Supreme Person, Maker and active Ruler of the world, is at the very root of Christianity” (57).

And, in terms of man, the liberal has reappropriated the pagan understanding of human nature. “. . . a remarkable change has come about within the last seventy-five years,” Machen writes. “The change is nothing less than the substitution of paganism for Christianity as the dominant view of life. . . . What then is paganism? . . . Paganism is that view of life which finds the highest goal of human existence in the healthy and harmonious and joyous development of existing human faculties. Very different is the Christian ideal. Paganism is optimistic with regard to unaided human nature, whereas Christianity is the religion of the broken heart” (66). “According to the Bible, man is a sinner under the condemnation of God; according to modern liberalism, there is really no such thing as sin. At the very root of the modern liberal movement is the loss of the consciousness of sin. . . . Characteristic of the modern age, above all else, is a supreme confidence in human goodness” (65). How different, though, is Christianity: “The truly penitent man glories in the supernatural, for he knows that nothing natural would meet his need; the world has been shaken once in his downfall, and shaken again it must be if he is to be saved” (109).

Given Liberalism’s merely human Jesus, its nebulous pantheistic God who can only be felt as though a Father and yet not known personally, along with its pagan ideal of human goodness that knows no sin, what, then, becomes of the Bible?

Historic Christianity affirms the inspiration of the

Bible which Machen explains as plenary inspiration. “. . . the doctrine of plenary inspiration does not deny the individuality of the biblical writers; . . . What it does deny is the presence of error in the Bible. . . . according to the doctrine of inspiration the account is as a matter of fact a true account; the Bible is an ‘infallible rule of faith and practice.’ Certainty that is a stupendous claim, and it is no wonder that it has been attacked” (76). “The modern liberal rejects not only the doctrine of plenary inspiration, but even such respect for the Bible as would be proper over against any ordinarily trustworthy book” (78). “The liberal scholar. . . must finally admit that even the ‘historical’ Jesus as reconstructed by modern historians said some things that are untrue.” (79) Thus the two religions of Christianity and Liberalism are clearly distinguished by their different foundations for their faith, “Christianity is founded upon the Bible. It bases upon the Bible both its thinking and its life. Liberalism on the other hand is founded upon the shifting emotions of sinful men” (81).

Standing in stark contrast with the monochromatic naturalism of theological Liberalism, true Christianity celebrates an exultant supernaturalism in full color.

The sum of all this is that Christianity and Liberalism have two different views of salvation. “Liberalism finds salvation (so far as it is willing to speak at all of ‘salvation’) in man; Christianity finds it in an act of God” (121). “Modern liberal preachers do indeed sometimes speak of the ‘atonement.’ But they speak of it just as seldom as they possibly can, and one can see plainly that their hearts are elsewhere than at the foot of the Cross. . . . the essence . . . is that the death of Christ had

Fall 2023 | 7

an effect not upon God but only upon man. Sometimes the effect upon man is conceived of in a very simple way, Christ’s death being regarded merely as an example of self-sacrifice for us to emulate” (122). “It is perfectly true that the Christ of modern naturalistic reconstruction never could have suffered for the sins of others; but it is very different in the case of the Lord of Glory” (132).

Liberalism produced spiritual maladies which were profoundly detrimental to the church and to Christians.

The idea of a substitutionary or vicarious atonement of Christ for sinners whereby his sacrificial death and shed blood cleanses believers of sin before God is utterly unacceptable for the Liberal.

Upon the Christian doctrine of the Cross, modern liberals are never wary of pouring out the vials of their hatred and their scorn. . . . They speak with disgust of those who believe “that the blood of our Lord, shed in a substitutionary death; placates an alienated Deity and makes possible welcome for the returning sinner.” Against the doctrine of the Cross they use every weapon of caricature and vilification. Thus they pour out their scorn upon a thing so holy and so precious that in the presence of it the Christian heart melts in gratitude too deep for words. It never seems to occur to modern liberals that in deriding the Christian doctrine of the Cross, they are trampling upon human hearts (124).

The Spiritual Maladies of Liberalism’s Counterfeit Christianity

Machen’s conclusion that Liberalism was a different religion from Christianity also led to the recognition that Liberalism produced spiritual maladies which were profoundly detrimental to the church and to Christians. “The greatest menace to the

Christian Church to-day comes not from the enemies outside, but from the enemies within; it comes from the presence within the Church of a type of faith and practice that is anti-Christian to the core” (164). “A terrible crisis unquestionably has arisen in the Church. In the ministry of evangelical churches are to be found hosts of those who reject the gospel of Christ. By the equivocal use of traditional phrases, by the representation of differences of opinion as though they were only differences about the interpretation of the Bible, entrance into the Church was secured for those who are hostile to the very foundations of the faith” (182).

Machen minces no words as he describes the fruits of theological liberalism that had entered into the Church by dishonesty (166ff). He speaks of the errors of modern liberalism (73); its rejection of the truth of Jesus (78) and its hatred of the cross (123); its rejection of the whole basis of Christianity (47); its vituperation of the past as seen in its attack on Calvin, Turretin, and the Westminster Divines (in which they actually attack the Bible and Jesus himself, not merely the 17th century) (45). The fruit of liberal theology and its false claims (19, 33, 36) are hopeless disillusionment (41), gloom, (42) and failure (43). As a return to paganism (66), its preaching is futile (69). In the process of giving up on Paul, they lose Jesus too (45). The result of Liberalism is a vague natural religion (63) that becomes a rival of Christianity (53).

Instead of having a doctrine that transforms hearts by good news that is historical in nature (46), Liberalism creates despair (38), as it leaves people in the cold humdrum of their own lives (41). The result is a brotherhood of beneficent vagueness (34) rather than a brotherhood of twice born sinners, a brotherhood of the redeemed (162). If at times liberals’ arguments seem plausible, they are in fact pitifully vain (39). Even when celebrated on stage or powerfully asserted, Liberalism simply portrays a spurious view of life (19, 41).

Tragically, Liberalism returns the church to medieval legalism (148, 182–183). Rather than advancing liberty, it creates spiritual slavery (148). Its expectations are powerless, because they emphasize the imperative that addresses the human will rather than the indicative that brings the truths and promises of God (47). It is not the human will that changes lives, but a story (48). And therefore, the stupendous supernaturalism of Christianity will not follow the liberals’

8 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

policy of palliation by diminishing Jesus’s messianic consciousness and his identity as the very God man in history (89).

Machen’s Stupendous Christian Supernaturalism

Standing in stark contrast with the monochromatic naturalism of theological Liberalism, true Christianity celebrates an exultant supernaturalism in full color (174). In Machen’s estimation, Christianity alone possesses the gospel that produces the warmth and joy of believers who have been transformed by the news that changed history and changes lives (136–137). This was, and is, Machen’s “stupendous” Christian supernaturalism. As a master wordsmith, Machen was ever conscious of the precision and meaning of his words, so it is significant that he used the term stupendous often to describe the verities of the Christian faith.

Derived from the Latin word stupeo, stupendous can be translated as stunned, benumbed, to be dazed, speechless, silenced, astounded, confounded, or aghast. When something is stupendous, it means that it is extremely impressive, causing astonishment or wonder. In Christianity and Liberalism, Machen used the word repeatedly and always in the context of the truths of historic Christianity but never in relationship with Liberalism. Machen thus emphasized the truths of the Christian faith by holding them forth as nothing less than supernatural in character and consequently extremely impressive. Indeed, for Machen, the truths of historic Christianity were stunningly true—especially when contrasted with the many pathologies of Liberalism that he perceived. Machen’s word choice is especially evident in various respects regarding Jesus: his messianic consciousness, his Person, his claims, his theology, and his mission. Each of these falls under Machen’s rubric of stupendous:

Jesus’s Person and Messianic Consciousness. “. . . the teaching of Jesus was rooted in doctrine. It was rooted in doctrine because it depended upon a stupendous presentation of Jesus’ own Person” (33). Jesus’s messianic consciousness led him to note that “the strange fact is that this supreme revealer of eternal truth supposed that He was to be the chief actor in a world catastrophe and was to sit in judgment upon the whole earth. Such is the stupendous form in which Jesus applied to Himself the category of Messiahship” (34).

Jesus’s Theology: “But even in the Sermon on the Mount there is far more than some men suppose. Men say that it contains no theology; in reality it contains theology of the most stupendous kind. In particular, it contains the loftiest possible presentation of Jesus’ own Person. That presentation appears in the strange note of authority which pervades the whole discourse” (36).

At its heart, Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism is

a book for the church.

Jesus’s Claims: “The sources know nothing of a Jesus who adopted the category of Messiahship late in life and against His will. On the contrary the only Jesus that they present is a Jesus who based the whole of His ministry upon His stupendous claim” (90).

Thus Jesus is the supreme example for men. But the Jesus who can serve as an example is not the Jesus of modern liberal reconstruction, but only the Jesus of the New Testament. The Jesus of modern liberalism advanced stupendous claims which were not founded upon fact—such conduct ought never to be made a norm. The Jesus of modern liberalism all through His ministry employed language which was extravagant and absurd—and it is only to be hoped that imitation of Him will not lead to an equal extravagance in His modern disciples. If the Jesus of naturalistic reconstruction were really taken as an example, disaster would soon follow (97).

Jesus’s Mission: “The otherworldliness of Christianity involves no withdrawal from the battle of this world; our Lord himself with his stupendous mission, lived in the midst of life’s throng and press” (159).

And as it is the Bible that brings these stupendous realities of Christ to light, biblical revelation itself partakes of this stupendous character for Machen:

“The Bible might contain an account of a genuine revelation of God, and yet not contain a true account. But according to the doctrine of inspiration, the account is as

Fall 2023 | 9

a matter of fact a true account; the Bible is an ‘infallible rule of faith and practice.’ Certainly that is a stupendous claim and it is no wonder that it has been attacked” (76). “And Paul does not hesitate to apply to Jesus stupendous passages in the Greek Old Testament where the term Lord thus designates the God of Israel. But what is perhaps most significant of all for the establishment of the Pauline teaching about the Person of Christ is that Paul everywhere stands in a religious attitude toward Jesus. He who is thus the object of religious faith is surely no mere man, but a supernatural Person, and indeed a Person who was God” (100).

The stupendous realities of Christ contained in the stupendous truths of the Bible lead Machen to a stupendous passage that teaches a stupendous change in the life of a Christian.

Machen extols the supernatural gospel Christianity of Paul found in Galatians 2:20: “Many are the passages and many are the ways in which the central doctrine of the new birth is taught in the Word of God. One of the most stupendous passages is Gal. 2:20. . . . That passage was called by Bengel the marrow of Christianity. And it was rightly so called. It refers to the objective basis of Christianity in the redeeming work of Christ, and it contains also the supernaturalism of Christian experience” (143). “‘It is no longer I that live, but Christ liveth in me’—these words involve a tremendous conception of the break that comes in a man’s life when he becomes a Christian. It is almost as though he became a new person—so stupendous is the change” (144).

Supernatural Christianity: The House of God and the Gate of Heaven

Machen’s consideration of stupendous Christian supernaturalism in relationship to Jesus, the Bible, and the new birth, enabled him to engage the Christian’s duties of evangelism and missions. It is such a thrilling message, that if Machen had written his little book in a previous era, when lengthy titles comprehensively proclaimed a book’s essential message, the title of Christianity and Liberalism might have been:

“How Stupendous Christian Supernaturalism with Its Joy of Salvation Rescues the Church from the Failed Modernist Attempt to Reconcile Historic Christianity with Naturalistic Science and Philosophy that Resulted in a Different Religion of So-Called Liberalism that

Abandons the History, Person and Work of Christ Along with All Biblical Doctrine Turning the Joy of the Gospel into Despair.”

It was clear for Machen that Jesus’s mission was pursued in a busy world. And so, Christianity was not to retreat from the world and its turmoil: “The otherworldliness of Christianity involves no withdrawal from the battle of this world; our Lord himself with his stupendous mission, lived in the midst of life’s throng and press” (159). And thus, with Jesus and his worldly gospel mission in mind, we can appreciate Machen’s emphatic call for Christian global evangelization. The church has been given a vast responsibility to carry on the Lord’s mission, a conviction that goes far to explain Machen’s determination to establish a biblically based independent board of foreign missions, a commitment that would cost him dearly (See Stonehouse, J. Gresham Machen, 469–493).

But as the conclusion of Machen’s century-old bestseller again sounds its clarion call for the defense and advance of supernatural Christianity, it also unfurls afresh his yearning for a “refuge from strife”; a “place of refreshment where a man can prepare for the battle of life”; a “place where two or three can gather in Jesus’s name.” Machen summons fellow believers to the “foot of the cross” for there is to be found “the house of God” and “the gate of heaven” (184).

At its heart, Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism is a book for the church, a book which equips her for defense by preserving biblical doctrine, and which equips her for mission by illuminating the powerful, hopeful, comforting message of Christ given for his people.

I thank God for J. Gresham Machen. He possessed, indeed, both the courage and the requisite scholarship to establish a theological legacy in defense of historic Christianity that remains vitally true a century after it first came off the press.

Peter A. Lillback (PhD, Westminster) is president and professor of historical theology and church history at Westminster Theological Seminary. He also serves as the president emeritus and founder of The Providence Forum and senior editor of Unio cum Christo: An International Journal of Reformed Theology and Life.

10 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

Thanks to your generous support,

Westminster has met its fundraising goal of $21.4M! We are looking forward to breaking ground soon on the new 35,000 square foot academic center, and for construction to begin in 2024.

Please join with us in praising God and praying that this incredible structure, equipped with the technology to capture and bring Westminster theology to the ends of the Earth, will deeply impact the residential experience and serve our growing online student body!

A MATTER OF INTEGRITY:

The Confessional Foundation of Christianity and Liberalism

Mark A. Garcia

J. Gresham Machen at the Princeton Checker Club

Karl Adam, a Roman Catholic theologian, famously wrote in 1926 that Karl Barth’s commentary on Romans fell like “a bomb on the playground of the theologians.” That may be true for academic theology, but for the life of the church one could argue that that epithet is more fittingly attached to J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity in Liberalism, published only three years earlier. Machen’s book is well-known for its strident defense of theological orthodoxy, but in fact his central concern was for integrity among those who claim to subscribe to the Westminster Standards and to embrace the polity of the Presbyterian church while denying both in practice. As the church has faced theological challenges since 1923, Machen’s book has proved to be among the most important, enduringly relevant works published in the last century. In our current crisis of integrity, Machen’s classic work may have yet more wisdom for us.

The Problem of Dissonance

What is our crisis of integrity? In fact, there are arguably multiple crises that fit this description, but I have a particular one in view, one that seldom receives much attention on account of (at least) our preoccupation with real cultural and theological problems outside ourselves. Within a few years of being in the ministry, freshly minted seminary graduates often struggle with the sobering dissonance between the idealism of belonging to a confessional church and the on-the-ground reality of what they witness. What one might expect in a body that cherishes, even parades, its confessional adherence and detailed polity runs up against the solemn reality of how that confession and polity sometimes function—and don’t—in the church’s work. And the closer one looks and listens, the more disturbing the picture can become. To protect the reputations of respected ministers or elders, carefully written and wisely worded provisions in a Book of Discipline designed to advance justice and truth might simply be ignored when consideration of their use is not only appropriate but explicitly requested by those affected. Speeches (and silences) on the floor of church courts may seem odd and unexpected, until one learns just how much of the church’s business is done at the water cooler or by text or e-mail or social media, rather than deliberated and debated publicly, or how strongly friendships

appear to function in church decisions. I once heard about a senior, respected churchman who gave a brief speech against consideration of serious concerns brought by anxious church members via a presbyter regarding the pastoral conduct of another minister. The concerns were summarily dismissed in the brief speech simply on the grounds that the accused was a long-serving and respected pastor. I could go on. And on.

Whereas seminary students and graduates may be inclined to affiliate with one communion or another based on what that communion is on paper, they seldom seek out the wisdom of those who are able to speak to the reality on the ground. Before long, they learn the wisdom of those who know better and advise, “since all communions have their problems, choose whose problems you want to live with.” The stories quickly pile up with experience, and before long, early idealism gives way—in some to cynicism, in others to departure from the ministry.

In my close to twenty years of teaching seminarians, mentoring ministers and elders, and advising church members and sessions or consistories in contexts of church discipline, I have been struck by how often Christians express concern with this phenomenon and yet how little minsters, elders, and other church leaders seem to recognize its effect on congregations. It’s not hard to understand why Christians struggle here. It is a sobering, scandalous thing to witness a reluctance, even refusal to use the heralded confessions and polity of our church when the welfare of the sheep of the Shepherd is at stake. In our church membership classes, candidates are routinely encouraged by their teachers to learn carefully the theology and polity of our churches. But watching pastoral ministry and church courts in action tends to prove to the saints that there is more going on than what our polity texts say. Our brothers and sisters in Christ are far more capable of recognizing the evidence of politicking and friendly alliances than their elders sometimes give them credit for.

In my most recent re-read of Machen’s classic, I was struck by something I had not noticed in earlier readings, at least not in the same way, namely, his timely concern with this matter of integrity in confessional contexts. In each topic he considers, from the nature of doctrine itself to the doctrine of the church, he is in fact summoning the reader to integrity, that fitting and necessary virtue discoverable in the coherence between professed commitment and courageous, though sometimes costly, practice. Of

Fall 2023 | 13

course, he knew this first-hand. We should read Machen with conscious sensitivity to the tragic relationship of his concern for integrity to his biography: he was prosecuted by a confession-subscribing and polity-committed church for a violation of church polity, while that same communion had failed—indeed refused—to prosecute others for theological heterodoxy. To forget this while reading Machen would numb us to much of the verve and vigor of his argument, and may blunt its potentially valuable force in our contexts. If, as I suggest, we are indeed facing a crisis of integrity in our confessional churches and related contexts, then Machen’s classic may be of real help to us yet again. To appreciate how this may be, however, we should recall how his concern with integrity reflects the unique story and conditions of American Presbyterian confessionalism.

The Adopting Act

Concerns with orthodoxy and integrity have gone hand-in-hand from the beginning of American Presbyterianism. The first American heresy trial concerned Samuel Hemphill, a promising young preacher recently arrived from Northern Ireland. The trial took place in the 1730s, soon after the “Adopting Act” of 1729. What was the subject matter of his heresy trial? In addition to concerns about dishonesty in his confessional subscription, he had plagiarized his sermons.1 Interestingly, the double-sided nature of this first heresy trial mirrors Machen’s concerns two centuries later. In fact, though anchored in Christian and Reformed foundations, Machen’s explosive missive belongs to the distinctly American presbyterian story of debates over confessional subscription, for which the 1729 Adopting Act is the touchstone.2

The Adopting Act aimed to resolve a vulnerability threatening early American Presbyterianism. The unprecedented level of detail in the lengthy Westminster Confession and Catechisms created a significant challenge to the traditional pattern of an unqualified subscription, and would in due course provoke a momentous turn in the history of symbolics.3 Apparently anticipating the difficulties of a full subscription, some Westminster divines opposed the imposition of subscription. It would not prove to be a practical difficulty in England, but in the American colonies the question took on fresh importance. In the 1690s, the Presbyterian bodies

in Scotland, England, and Ireland had each adopted the Confession and required subscription to it. But this prompted great unrest in each of these contexts as controversies ensued over the disconnect between the intention of the subscription requirement (protection against heretodoxy) and the actual result of it (failing to protect against heterodoxy, or leading to great concerns over the imposition of a merely human standard, or both).

What if subscription on the part of ministers is required, but it is not enforced in the application of its polity?

In 1721, the Synod of Philadelphia received an overture requiring subscription to the Westminster Standards. This led to a sermon the following year, preached by Jonathan Dickinson, which denounced the idea of submitting to a man-made document rather than only to the Bible. For Dickinson, such subscription would represent a reversion to the Romanism from which they escaped rather than a proper embrace of the sufficiency of Scripture for the church’s faith and life. In the years to come, tensions grew as immigrants arrived from across the Atlantic, resulting in a division between the Scots and Scots-Irish who favored, and the New Englanders who opposed, confessional subscription. In 1727, another overture was presented, this time by John Thomson, which called for confessional subscription by all ministers and ministerial candidates, advancing with special emphasis the value of subscription for keeping at bay the various dangerous errors of the time. Again Jonathan Dickinson responded, arguing that if the need for subscription is rooted in the need to defend the gospel, all Christians must defend the gospel, and so, by parity of reasoning, all Christians would have to subscribe to the standards, a requirement that, under the circumstances, would only further divide and confuse the American church.

The “Adopting Act” of 1729, in which American Presbyterianism accepted a form of confessional

14 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

subscription, represented a compromise on the question and an innovation in the history of symbolics. For members of the American Presbyterian church, no subscription would be required, for the gates of the church should be as wide open as the gates of heaven may be. For ministers and prospective ministers, however, a qualified subscription would be expected, one which still allowed for individual scruples. The agreement was reached in the morning of September 19, 1729, and that afternoon several ministers presented various scruples, all of which were determined to be acceptable in terms of the agreement reached that morning.

The story doesn’t end there, of course. In the next decade, “strict subscriptionists” unsuccessfully attempted to impose their model of subscription on the church by claiming that that had been the intention of the 1729 Synod. Instead, the church’s resolution reached with the Adopting Act became the foundation of American Presbyterian life and a principal factor in the subsequent story of that Church, becoming fixed as a matter of constitutional law by the 1788 Synod.

As James Payton explains, the Adopting Act represented a divergence from the traditional understanding of subscription up through the Reformation, a divergence provoked by the level of detail and comprehensive scope of the Westminster Standards and the unique circumstances of colonial American Presbyterianism. Whether one views the Act’s compromise favorably or unfavorably, the settlement in favor of subscription to the “system of doctrine” proved unstable in subsequent generations, and invited the phenomenon of various presbyteries and communions with marked differences from one another. In some of these contexts, the Westminster Standards’ role was eventually reduced infamously to the level of providing mere “instruction and guidance,” as in the 1967 modification reached by the United Presbyterian Church.

Christianity or Liberalism: The Adopting (But Not Using) Act

This backstory belongs to the context in which Machen found himself in the early twentieth century. His work breathes the air of this environment, and represents a vigorous attempt toward a course correction, but with a difference. The concerns with heterodoxy and biblicism that had led to the

decisions of 1729 and 1788 would, in Machen’s context, admit of a third. What if subscription on the part of ministers is required, but it is not enforced in the application of its polity? What if the enforcement that does take place is selective, reflecting personal or ideological motives? Machen’s book is in part a response to Harry Emerson Fosdick’s 1922 sermon, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” and also the expansion of a well-received public presentation to the Chester Presbytery in 1921 (published by The Princeton Theological Review a year later), but his argument in fact reaches further and deeper than responding to Fosdick’s provocation. For Machen, subscription is important, but no model of subscription is sufficient, for the very best confession of faith and church polity ever imagined is useless, or worse, when not rightly used. This is the context of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism, which is not fundamentally an argument regarding theology or confessional subscription, but regarding integrity. Repeatedly in his work, we note his concern with matters of morality and not only of orthodoxy. For Machen, a church needs both a creed or confession and a form of government by which the content of that confession can be preserved from error. But that government requires men of integrity, or else the confession is worth less than the proverbial paper it’s printed on. This is where Machen saw the sinister danger lurking in liberal theology. In the introduction to his book, Machen defends the need to present the issue of his day “sharply,” and refers as well to how many in his day preferred to engage intellectual battles in what Francis L. Patton called “a condition of low visibility.” The issue, sharply identified by Machen, was between Christianity and its lethal liberal counterfeit. But their difference, he argued passionately, is not at the level of the words on paper but our relationship to them. The true nature of Liberalism is, he insisted, “hidden by the duplicitous use of traditional terms and categories by liberal clergy” who lacked the integrity to either honestly announce their disagreement with the confession or to discipline those who show by their preaching or practice that they reject it.

Heirs of Machen?

Machen’s words sit comfortably alongside the more recent remarks of theologian John Webster:

Fall 2023 | 15

We should be under no illusion that renewed emphasis upon the creed will in and of itself renew the life of the church: it will not. The church is created and renewed through Word and Spirit. Everything else—love of the brethren, holiness, proclamation, confession—is dependent upon them. Yet it is scarcely possible to envisage substantial renewal of the life of the church without renewal of its confessional life. There are many conditions for such renewal. One is real governance of the church’s practice and decision-making not by ill-digested cultural analysis but by reference to the credal rendering of the biblical gospel. Another is recovery of the kind of theology which sees itself as an apostolic task, and does not believe itself entitled or competent to reinvent or subvert the Christian tradition. A third, rarely noticed, condition is the need for a recovery of symbolics (the study of creeds and confessions) as part of the theological curriculum—so much more edifying than most of what fills the seminary day. But alongside these are required habits of mind and heart: love of the gospel, docility in face of our forebears, readiness for responsibility and venture, a freedom from concern for reputation, a proper self-distrust. None of these things can be cultivated; they are the Spirit’s gifts, and the Spirit alone must do his work. What we may do— and must do—is cry to God, who alone works great marvels.4

As both Machen and Webster recognized, the question of integrity is not only before the local and regional expressions of the church, but also before the institutions and organizations that serve the church in some way. In our time, as institutions of theological education scramble to reinvent themselves in a new, challenging economic, ecclesiastical, and cultural environment, we have the opportunity to feature in that reinvention a recovery of the priority of moral formation as central to ministerial education. It must matter again what kind of men we are training for service in the church, and not only how well they can recall and repeat the words of our rightly cherished confessional standards.

But Machen’s chief target is the visible church. Since Machen’s day, many have wanted their own

theological and ecclesiastical efforts to be seen as falling under the aegis of his. But the person in our day who truly breathes the air of Machen’s tour-de-force will not only concern himself with an attachment to the Confession and Book of Order but also with their proper, impartial, and courageous (because sometimes costly) use. To him, failure of nerve and lack of courage will be as repugnant as ignorance and incompetence. To him, silence in a just cause will be outrageous. As a man of integrity, he will be—he must be—as averse to the disingenuous and duplicitous as he is the erroneous and heterodox.

Mark A. Garcia (PhD, Edinburgh University) is associate professor of systematic theology. Garcia is also the founding President and Fellow in Scripture and Theology at Greystone Theological Institute He served as pastor at Immanuel Orthodox Presbyterian Church (Coraopolis, PA) from 2007–2021. He was Senior Member and Post-doctoral Research Associate at Wolfson College and Visiting Scholar in the Faculty of History at Cambridge University from 2006–2007, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of East Anglia from 2014–2018, and has taught theology regularly as an adjunct professor at Westminster and other Reformed seminaries since 2007.

1. Plagiarizing one’s sermons is something which I have yet to see appear on the disciplinary floor of contemporary presbyterian church courts. To read about the trial, see A Vindication of the Reverend Commission of the Synod: in answer to some observations on their proceedings against the Reverend Mr. Hemphill (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, 1735).

2. On the Adopting Act, see James R. Payton, Jr., “The Background and Significance of the Adopting Act of 1729,” in Pressing Toward the Mark: Essays Commemorating Fifty Years of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, ed. by Charles G. Dennison and Richard C. Gamble (Philadelphia: The Committee for the Historian of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, 1986), 131-145.

3. See Payton for fuller discussion of these points.

4. John Webster, “Confession and Confessions”, in Confessing God: Essays in Christian Dogmatics II (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 83; as quoted by Stafford Carson, “Recovering Reformed Catholicity,” Theology in Scotland 26(S) (2019): 20.

16 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

greystone theological institute member ship

Hundreds of hours of robust theological content for only the price of a paperback

for only $18 a month

greystone member benefits include

• The entire Greystone course library (with new content added regularly)

• Greystone Reading Room events

• Texts & Studies, a Greystone publication series featuring short studies and serialized new translations of important theological works from Church history

• Biweekly Gleanings newsletters with reading recommendations from experts

• Support for global Reformed theology and ministry

exclusive offer get your first month free with code wtsmag

Old Testament Exegesis ∙ Theological Anthropology ∙ Union with Christ ∙ The Trinity and the Gospel ∙ Hermeneutics ∙ & More! institutional memberships are also available for groups and institutions at a significantly reduced rate

• All benefits of the individual membership, plus:

• Share Greystone course library with students, faculty, alumni, staff, church, etc.

• Discounts on Greystone events and courses, and more! for more info visit greystoneinstitute.org/membership For inquiries regarding our institutional rate, email info@greystoneinstitute.org

TELLING THE TRUE GOSPEL:

The Reception of Christianity and Liberalism in Chinese Churches

Shao Kai Tseng

J. Gresham Machen manuscript page (Christianity and Liberalism)

The Chinese translation of J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism by Samuel Boyle (包義 森, 1905–2002) is of foundational importance for the evangelical church in China. And yet, though published in 1950, this magnum opus did not gain traction until around the 1990s. Then, to satisfy growing demand, a second edition was published in 2003, with a preface by the late Jonathan Chao (趙天恩, 1938–2004), and a third in 2020 along with an e-book version.

A missionary from the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America, Boyle began translating Machen’s explosive text into Chinese in 1940. According to Chao’s preface, Boyle finished the first draft in about a year, and brought it to Guangzhou in 1947.1 In December 1948, Boyle was introduced to the young Charles Chao, Jonathan’s father, by none other than Lorraine Boettner and Johannes G. Vos.2 Boyle and Chao established the Reformed Translation Fellowship (RTF) Press, and they would work on many projects together in the years to come.

The communist takeover in 1949, with all of its theological implications, exposed an urgent need for the publication of Christianity and Liberalism in China. A form of theological liberalism, which was primarily American rather than German, had made its way to China around the turn of the twentieth century. It was first introduced to Chinese Protestants through organizations like the YMCA, which became active in China as early as the 1870s, and the National Christian Council of China (NCCC, 中華全國基督教協進會), founded in 1913.

Initially intended to include all denominations and missionary organizations in China, the NCCC’s progressive origins and its increasing advocacy for the social gospel soon began to alarm the more conservative leaders of Chinese churches. In 1926, China Inland Mission, founded by the great James Hudson Taylor (1832–1905), withdrew from the NCCC. In 1950, the NCCC adopted a proposal by the social gospel proponent Wu Yao-tsung (吴耀宗, 1893–1979), co-founder of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement,3 to cut off all ties to foreign Christian groups and swear allegiance to the Communist Party. The rise of the communist regime in China was, in this and other ways, the culmination of the kind of progressivism that began to permeate cultural scenes in the nation around the turn of the century, and American theological liberalism was part and parcel of this progressivism.

Conservative church leaders and missionaries in China were opposed to the social gospel to begin with, and they saw the rise of the Communist Party as the culmination of this false theology. They were opposed to the Three Self-Movement as well, because they were opposed to all false gospels. This tenacity for faithfulness is preserved in the widely circulated 1955 article, “We, Because of Faith,” by Wang Mingdao (王明道, 1900–1991), honored by many in the West as the “dean of the Chinese house churches.” 4

In Chao’s view, Christianity and Liberalism was and remains an important response to political life in China.

In his 2003 preface to Christianity and Liberalism, Jonathan Chao commented that the Three-Self Movement had always been characterized by theological “revisionism” that “subjects the Christian faith to the standards of socialism and dialectical materialism . . . emptying the Christian faith of its contents.”5 It was thus of the same nature as the kind of liberal theology imported from America. Chao was thus confident that “this book by Machen remains relevant to Chinese churches of the twenty-first century.” 6 In Chao’s view, in other words, Christianity and Liberalism was and remains an important response to political life in China. This partly explains why, in 1949, Jonathan’s father Charles decided to edit and publish Boyle’s translation—and there were strong indications that conservative church leaders would appreciate its value.

According to Hong Kong-based church historian KaLun Leung (梁家麟), Wang Mingdao’s text, Discerning the True Gospel (《真偽福音辨》), ranks among the most significant pieces of Sinophone Christian literature of the twentieth century.7 And Wang’s book, the title of which, literally translated, is “telling the true gospel apart from the false,” has in fact played somewhat of a similar role

Fall 2023 | 19

in the Chinese context as that of Machen's in America. Wang’s relentless critique of the social gospel would come to represent the definitive watershed between fundamentalism and Liberalism in Chinese Protestantism for decades to come.

Boyle and Chao adopted the “telling the true from the false” rhetoric made popular by Wang for the Chinese title of Christianity and Liberalism, Jidujiao Zhenweibian (《基督教真偽辨》), literally meaning “telling true Christianity from the false,” clearly an allusion to Wang’s influential treatise. And there are many similarities between the two works. Both are polemical. Both were written to defend the gospel. The former sought to refute social gospels from America, and the latter, liberal theology in America.

Christianity and Liberalism is of foundational import to the work of the RTF Press and to the Chinese Reformed movement in general.

There are, however, noteworthy differences as well. The arguments in Christianity and Liberalism are grounded on established academic research. The author spent a year in Germany as a student of theology and had been exposed to the challenges of Liberalism firsthand. The work as such invites critical thinking on the part of the reader.

Discerning the Gospel, by contrast, is didactic and homiletic in its tone, and pietistic in its content. Fraught with threats, warnings, and derogatory remarks against “false prophets,” this treatise offers very little theoretical analysis of the social gospel.

Most conservative Chinese Christians were so accustomed to this style of teaching that they were hardly prepared for a work like Christianity and Liberalism when it was first published in Chinese. Fundamentalist struggles against Liberalism in Chinese Protestant circles were for

the most part driven by pietistic impulses that tended to be anti-intellectual. For decades, fundamentalist Christians in Chinese churches equated the term “theology” with “liberalism,” and deemed all academic and critical attempts at understanding the faith to be apostate. Perhaps that was the only way they knew to defend Christ’s little ones and his true gospel, once they no longer had foreign missionaries to help them.

Evangelical Chinese churches did not hold academic theology in high regard until the 1970s, when a group of Chinese alumni who attended Westminster Theological Seminary in the 1960s, including Jonathan Chao, launched a campaign for theological education. Their work led to the founding of China Evangelical Seminary in Taiwan and the China Graduate School of Theology in Hong Kong, in 1970 and 1975 respectively. The campaign eventually won the support of local churches and foreign missionaries, not least owing to the influence of the 1974 Lausanne Congress and the consequent founding of the Chinese Congress on World Evangelization in 1976.

Jonathan Chao also founded numerous underground theological training centers across mainland China. He and his colleagues at China Missions International brought to the mainland books and cassette tapes featuring sermons and theology seminars by his close friend and ally, Stephen Tong (唐崇榮), whose contribution to the popularization of Reformed theology in Chinese churches remains unparalleled. The once-seemingly obsolete publications of the RTF Press suddenly became widely circulated among Chinese Christians in mainland China and beyond in the 1990s.

Despite its quiet rise to prominence, today Christianity and Liberalism is of foundational import to the work of the RTF Press and to the Chinese Reformed movement in general. Not only was it the first book ever published by the press, but it was also the first Chinese publication of a theological volume that presents an intellectual and critical way of clarifying and defending sound doctrine.

Regrettably, receptions of the work in Chinese contexts up to our own day have not always reached the author’s intended results. To honor Machen’s classic, then, I shall conclude by way of two caveats.

Machen’s intent is stated at the very beginning of the treatise:

20 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

The purpose of this book is not to decide the religious issue of the present day, but merely to present the issue as sharply and clearly as possible, in order that the reader may be aided in deciding it for himself. Clear-cut definition of terms in religious matters, bold facing of the logical implications of religious views, is by many persons regarded as an impious proceeding…, but it is always beneficial in the end.8

Despite this explicit statement, many Chinese readers, and in fact many American readers as well, still approach the work with an anti-intellectual mindset. The polemical tone of the book easily appeals to the fundamentalist mind that regards “clear-cut definition of terms” and analyses of “the logical implications of religious views” as “an impious proceeding.” Critical analyses in the book can easily be overshadowed by the polemics for the fundamentalist reader who, after having read the book, still regards fair-minded theological debate with suspicion. A striking phenomenon is that many Chinese church leaders have presented Christianity and Liberalism with the kind of derogatory rhetoric found in Discerning the Gospel. One widely circulated online review, for instance, describes “Machen” as “making fun” or “laughing at” the “failed attempt of the new theology,” and “liberalism” as “wishful thinking [一廂情願],” “poison to the soul,” “pathetic and ludicrous [啼笑皆非],” “apostate,” and “entirely bankrupt.” 9 This way of defending the faith, I am afraid, runs contrary to the intent of the author.

My second caveat applies to both Chinese and American readers: we must avoid relying on Machen’s volume as if it were an inspired text. Its context is significant. For one thing, Christianity and Liberalism was in large part a response to a specific sermon by Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878–1969), titled “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”10 And so the form of Liberalism that Machen sought to address was a specific brand of American theology. Schleiermacher is not mentioned at all, and the only mention of Kant reflects a now debunked mischaracterization of Kant’s critique of metaphysics as an “attack upon the theistic proofs.”11 Machen’s criticisms, then, can hardly apply to every strand of liberal theology that has influenced America and China today.

Machen the mountaineer

Fall 2023 | 21

Liberalism was not monolithically guided by ‘Enlightenment naturalism.’ In fact, some liberal theologians like Ernst Troeltsch (1865–1923), rejected the kind of naturalistic consciousness characteristic of the later Ritschlians and sought to honor the immanence of divine revelation in history—however much that immanentization went too far. Naturalistic consciousness—what Weberians have described in terms of “disenchantment”—was only a first moment in the development of theological modernism. A second and more predominant moment was that of re-enchantment, the sacralization and transcendentalization of nature and history, to borrow from German sociologist Hans Joas.

Academic theologians and seminary students today should follow Machen’s example and study Liberalism for themselves.

This is a relevant note for our own day because this re-enchanting form of liberal theology, once espoused by German theologians like Troeltsch and Emanuel Hirsch (1888–1972), has re-appeared in some conservative Christian circles in America under rubrics such as “Christian nationalism.” If our understanding of theological liberalism remains too narrowly focused on the naturalistic modernism addressed in Christianity and Liberalism, we can easily miss grave ideological dangers that are right under our noses.

Machen has run the good race. His work remains pertinent to churches worldwide even a century after its initial publication. Academic theologians and seminary students today should follow Machen’s example and study Liberalism for themselves. His express intent was never to do the homework on Liberalism

for us, but rather to call each one of us to do our own homework and continue to engage Liberalism, and any theological aberration whatsoever, with academic seriousness and integrity, so that we might, in the words of brother Wang Mingdao, tell the true gospel apart from the false.

Shao Kai (“Alex”) Tseng (MDiv, Regent College; ThM, Princeton Theological Seminary; MSt, DPhil, University of Oxford) is research professor in the philosophy department of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China. He is the author of Karl Barth’s Infralapsarian Theology and Barth’s Ontology of Sin and Grace, as well as books on Hegel, Kant, and Barth in the Great Thinkers series (P&R), and a contributor to the Oxford Handbook of Nineteenth-Century Christian Thought.

1. J. Gresham Machen [梅晨], Christianity and Liberalism [基督教真 偽辨], ed. Charles Chao [趙中輝] and John Shen [沈其光], trans. Samuel Boyle [包義森] (Taipei: CRTS Books [改革宗出版社], 2020), 11.

2. Ibid., 12.

3. A Chinese government organization devoted to the removal of foreign influence in the church.

4. Wang Mingdao [王明道], “We, Because of Faith [我們是為了信 仰],” in The Wang Mingdao Collection [王明道文庫], volume 7 (Taichung: Conservative Baptist Press, 1998), 320.

5. Ibid., 16.

6. Ibid., 15.

7. Wang Mingdao [王明道], Discerning the True Gospel [真偽福音辨] (Taichung: Morning Star, 2000). See Ka-Lun Leung, “A Hundred Years of Sinophone Christian Writing [百年回顧:華人基督 徒著作],” in Faith Monthly 6 (August 2003): http://www.godoor .com/xinyang/article/xinyang6-11.htm (accessed 21 July, 2023).

8. J. Gresham Machen, Christianity and Liberalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 1.

9. See Li Xian [李賢], “New Theology or Fake Theology? A Review of Christianity and Liberalism [新神学还是假神学? 《基督教真 伪辩》书评],” Christian Sermons [基督教講道網], http://www .jiangzhangwang.com/shenxue/22656.html (accessed 22 July 2023).

10. Mark Noll, A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 343–344.

11. Machen, Christianity and Liberalism, 50.

22 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

IT’S BEEN 100 YEARS. WHY

YOU READ CHRISTIANITY & LIBERALISM YET?

edition

hope

one

reformation

renewal. Visit christianityandliberalism.com to learn more

HAVEN’T

Now available in a new

with the

that this next century will be

of

and

KUYPER’S CAUTION :

Remain Faithful to Christ in Cultural Conflict

William R. Edwards

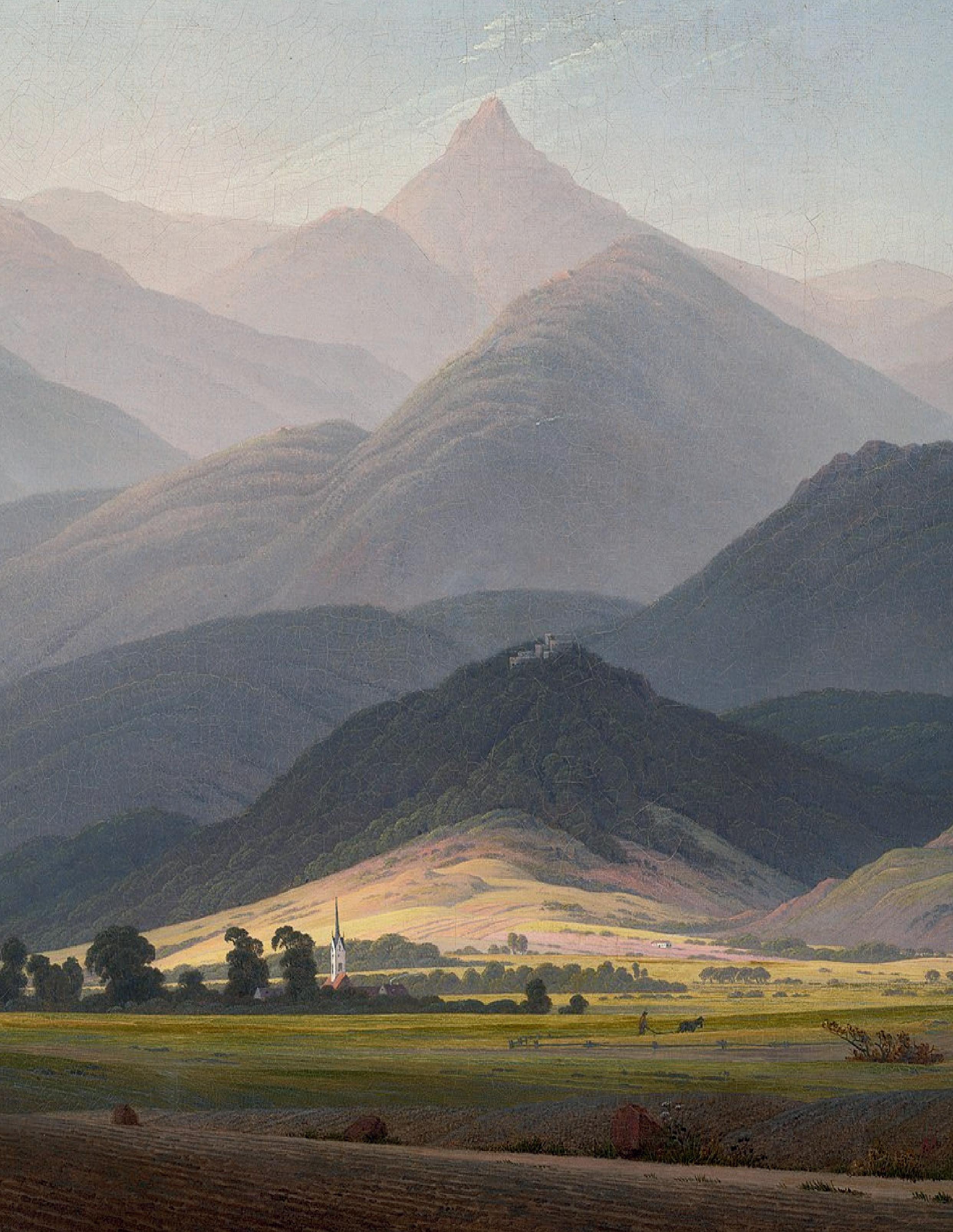

Mikhail Konstantinovich Clodt, In The Fields (1872)

Sermons often do not age well. Assuming the exegesis of Scripture is faithful, the preacher’s context has nonetheless changed. Thus, it is typically ill-advised to take a sermon preached years-past and simply re-present it with the expectation that it will apply equally well in a different place and time for different people. If this is true for sermons pastors preach over the course of their own ministries, how much truer for a sermon preached more than one hundred and fifty years ago? And yet, Abraham Kuyper’s 1870 sermon, “Conservatism and Orthodoxy: False and True Preservation,” retains a contemporary ring worthy of renewed interest, especially for American Christians.1

Kuyper’s sermon, of course, has a specific context of its own. This was his final sermon preached at the church he pastored in Utrecht as he was departing for a church in Amsterdam. His brief three years in Utrecht had proved increasingly difficult, not due to typical pastoral problems that had turned personal but to broader cultural matters and differences as to how they should be approached. According to James Bratt, Utrecht was the “capital of national ‘God and Country’ conservatism” within the Netherlands of the late nineteenth century.2 Kuyper was initially seen as an ally in that conservative cause, leading to his call there. However, Kuyper identified a confusion between the priorities of the church and the preservation of cultural power, leading to a parting of ways. The conservatives in Kuyper’s context valued the institution of the church foremost for its social influence. Kuyper argues this disregards the true essence of the church, as distinct from other social institutions, with the result of diminishing the church’s deeper impact on society.

Perceiving the church as an instrument of a conservative social agenda resonates in our day. Those on the right and those on the left may reduce the church to a mere cultural force, as either a friend or a foe to its own agenda. Contemporary caricatures of so-called Christian nationalism abound, favorably promoted by some while fearfully portrayed by others. Of course, Kuyper’s historical context is different from our own. We should not expect a direct correlation between his time and ours regarding matters related to the church or the culture. However, there are points of comparison. And more importantly, as Kuyper addresses the issues of his own day, he provides a theological vision for the church that countered the social constructs of both the

conservative and progressive causes of his time, which may serve us in our own.

The Problem of the Church: The Primary Problem of the Day

In his departing sermon at Utrecht, Kuyper claimed that “the problem of the church” is “the primary problem of the day.”3 Even more strongly, Kuyper states that “the problem of the church is none other than the problem of Christianity itself.”4 This conviction is evident across Kuyper’s writings, from his first published work to his final articles.5 Some of the problems Kuyper addresses are unique to the Netherlands in the nineteenth century. They concern the status of a national church with a complex history between “Christianity and Dutchness” where “church and nation were tightly interwoven.”6 The entangled relationship between church and state had implications for church oversight, church property, church membership, and the calling and paying of church pastors. While Kuyper spoke to these various problems, he believed that the problem itself was more substantial, which concerns the church’s core identity in God’s redemptive purpose, and how that identity must in turn determine its relationship to the world.

The church’s form cannot be derived from worldly power structures but must arise from its own life in relation to Christ.

Kuyper is well-known for distinguishing the church’s essence from its form, typically using the category of organism to describe the essence of the church and institution to address its form.7 Kuyper criticizes those conservatives who valued the church for its cultural capital and institutional weight while neglecting the vitality of the church which is found in its essence as the living body of Christ.8 This vitality gives the church its true power and influence in the world. Kuyper characterizes the conservatives of his day as “committed to externality”

Fall 2023 | 25

and “infatuated with the surface of things.” 9 However, the church is “a unique organism and requires a unique institution.”10 The church’s form cannot be derived from worldly power structures but must arise from its own life in relation to Christ. Essence and form, organism and institution, must not be torn asunder.

Kuyper’s distinction between the church as organism and the church as institution has been the source of much discussion.11 According to Bratt, Kuyper’s “theory moved from his earlier institute-organism distinction to an institute-organism opposition.”12 Earlier, as evident in his departing sermon at Utrecht and his inaugural sermon at Amsterdam, the inseparable relationship between organism and institution is prioritized. Kuyper uses the analogy of a snake’s protective skin, which is “a result of the vitality of the life which manifests itself at every point on its surface.”13 This external feature is both dependent on and essential to the living organism as the institutional church is to its organic life. He also uses the example of a river and its banks: the flowing waters analogous to the vital life of the church and the banks that carry its current similar to the church’s institutional form, preventing its flow from dispersing and halting its course.14 As Kuyper says, “From the organism the institution is born, but also through the institution the organism is fed.”15 Both are essential and function together.

Kuyper’s later writings, however, portray a problematic relationship between the church as an organism and as an institution, which has led to criticism.16 Yet it should be recalled that Kuyper initially develops the distinction in seeking to solve “the problem of the church,” in response to those who merely valued the institution of the church in relation to its relative usefulness in addressing wider social concerns while neglecting its life-giving essence. While Kuyper was also critical of modernism, as will be noted below, the more immediate threat to the life of the church he believed to be conservatism, at which he takes aim as he departs Utrecht.

The Spirit of Conservatism Contrasted with the Vital Life of the Church

The text for Kuyper’s sermon is taken from Revelation 3:11, “Hold fast to what you have, so that no one may seize your crown.” The verse is wellsuited for Kuyper’s careful critique. The exhortation to

“hold fast to what you have” commends, even commands, a type of conservatism. Careful preservation is required. Christianity possesses a conservative impulse. After all, Kuyper says, “Christianity came to save.”17 This stands in contrast to a revolutionary impulse: “Revolution demolishes and destroys.”18 Those who embrace revolution, Kuyper says, “rave about a better world.”19 We might think of the progressive spirit of our own day, both outside and inside the church, which seeks to deconstruct all that is part of the past and put something new in its place. Kuyper, though, says this is not the approach of Christianity, which resurrects the existing body to new life. The gospel does not destroy and replace but redeems and renews.

If the vitality of the church is derived from past forms rather than Christ’s present work, a dangerous sort of conservatism may have taken hold.

This conserving impulse of Christianity, however, may attract the church toward a type of conservatism that is opposed to genuine orthodoxy. Christianity and conservatism are both concerned with preservation, but they differ in what they aim to preserve. Whereas Christianity holds fast to the principle of life that is found in Christ alone, mere conservatism aims to preserve the life it currently possesses in the present age. “To be conservative in that sense,” says Kuyper, “is to block Christianity from pursuing its goal,”20 which is not the life we’ve presently attained, but an increasingly renewed life, through persevering faith in Christ. According to Kuyper, false conservatism fails to recognize the overwhelming impact of sin and therefore “seeks to dam up the stream of life, swears by the status quo, and resists the surgery needed to save the sick.”21 Conservatism, like progressivism, is uninterested in a gospel that redeems and renews.

26 | W ESTMINSTER M AGAZINE

Instead, it seeks safety in maintaining its social status rather than pursuing a salvation that counters sin and calls us to new life.

In the conflict with the revolutionary threat of progressives, the church may be tempted to make an alliance with a form of conservatism that is contrary to the renewing work of Christ. Kuyper warns that “many are joining our ranks whose goal is not, as is ours, the victory of Christianity but merely the triumph of conservatism.”22 These may be identified through their strategies. Conservatism that is counter to Christianity is satisfied to repristinate both church and culture based on a prior age. “If only we could have lived then!”23 If the vitality of the church is derived from past forms rather than Christ’s present work, a dangerous sort of conservatism may have taken hold. Lacking the ability to repristinate, conservatism aims to preserve “that which is still left of the legacy.”24 Or if all else fails, content itself with the ever-diminishing features that remain.25 The strategy of conservatism is to hold tight, but this inevitably ends in disappointment. “‘Always flow and never reverse yourself’ is the high decree that the Creator himself laid down for the stream of time.”26 In contrast to these conservative strategies, Kuyper says one must “first seek to have for yourself the life your fathers had,” and, “Then articulate that life in your own language as they did in theirs.”27

As noted above, Kuyper’s critique of conservatism does not place him within the progressive camp of his day. A year after his Utrecht sermon critiquing conservatives, he delivered a lecture exposing the ephemeral nature of modernism, referring to it as a “Fata Morgana,” an image that appears on the horizon that has no true substance of its own but is a reflection of a distant object through the refraction of light.28 Its transient existence depends on the presence of something else. Modernism has this character. Its existence depends on the truth that Christianity alone provides. However, though conservatism and modernism appear diametrically opposed, Kuyper argues that the conservatism he critiques helps create the atmospheric conditions for modernism. According to Kuyper, such apparitions appear in “times of spiritual aridity in which no fresh breeze could blow through the heart of the nation,” claiming that when “the spiritual atmosphere has the right kind of ferment, then heresy is bound to appear.”29 Surprisingly, status quo conservatism, which aims to repristinate the past, shares the blame for modernism as an inevitable response. In

fact, Kuyper believed modernism was a blessing for this very reason, awakening the church from its conservative slumber. Kuyper says that “without the Modernists we would still be groaning under the leaden weight of an all-killing Conservatism,” and for this reason, “Modernism has saved orthodoxy in the church of Jesus.”30

The church must labor to preserve and defend the historic facts on which the Christian faith depends, including Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection, as recorded in God’s word.