3 minute read

2023 : AN A.I. ODYSSEY

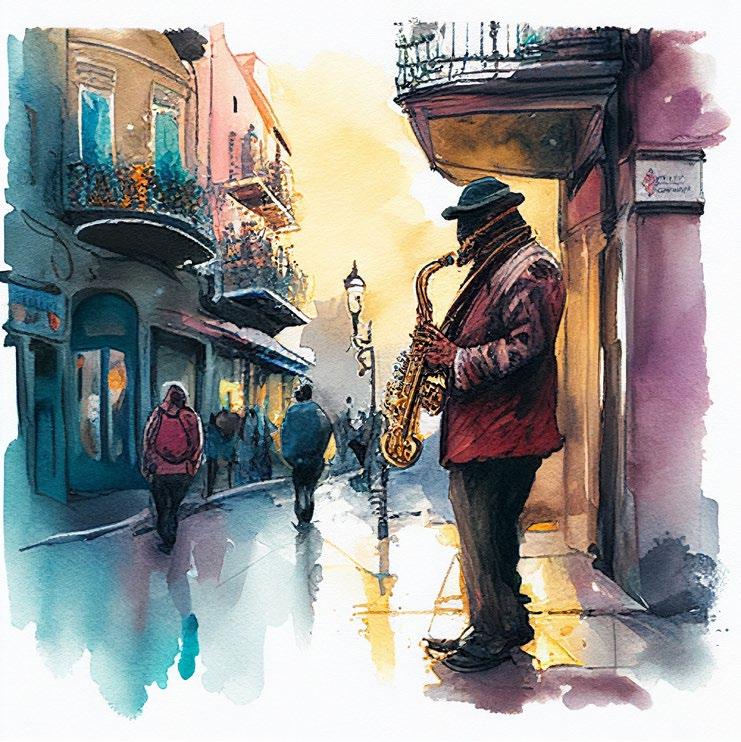

Is NOLA's Art Scene ready for Artificial Intelligence?

This picture was created from the above text using Midjourney, an AI-image generator. Even more impressive is that it rendered it, along with three alternates, in under one minute—infinitely less than 1% the amount of time it would take a seasoned artist to produce just one.

AI has quickly become the hot-button tech-topic of 2023. Google CEO Sundar Pichai heralds it as the most important human invention since fire or electricity; likewise, engineers integral to its development have warned it is the most dangerous innovation we have conjured up since the atom bomb.

Regardless, the genie is out the bottle. As every major tech company races to develop the one AI to rule them all, we are all along for the ride.

“I often joke that AI is a solution waiting for a problem,” says Ron Domingue, a local digital artist and an adjunct professor teaching digital art at Loyola University.

“One AI discovered eight radio signals in space just like that—something scientists haven’t been able to do for years, even with all of our analysis. It is solving problems we don’t even know are problems yet.”

A 3D-illustrator at stock-image provider Shutterstock, Domingue has been experimenting with AI-image generation software since its inception. His experience navigating the various applications for AI art, as well as its ethical considerations, landed him a coveted speaking panel on the topic at this year’s South by Southwest festival.

Domingue believes it won’t be long before big company’s begin employing AI efficiency experts, in much the same way that Social Media Officers became a new speciality last decade.

“You are going to have business experts asking, ‘Can we solve this problem with AI instead of actually getting an artist?’” Domingue foreshadows. “Artists will need to know where their spot is and be able to fill that gap; otherwise, they will get passed up by this technology.”

This future is already beginning to take shape. Earlier this year, Netflix released the Anime-short The Dog & The Boy using AI-generated art for its backgrounds amid an animator shortage.

On a macro-level, articles abound pontificating which industries will be left extinct in AI’s wake. However, in the tiny societal microcosm that is New Orleans, what threats and opportunities does AI-hold for a city that has served as a muse to some of the world’s most renowned artists, musicians, and writers? Could the many artists in Jackson Square capturing our cultural beauty in their works be cast aside by an algorithm that can churn out 100-unique images like the one above in a matter of minutes?

Here, Domingue believes the ball is still in the artists’ court.

“There will always be a demand for tactile art,” he argues. “A print of a famous work of art may go for a few bucks, but the original oil and canvas can fetch millions. At this point, digital art can just mass produce prints.”

Domingue further argues that buyers are now keen to the possibility of an image being AI-generated, much the same way we are accustomed to easily sniffing out poorly photoshopped pictures, making originals in greater demand.

“It’s the old adage of if you plagiarize one source, you’re stealing; if you plagiarize many, you are creating,” he quips. “Like Netflix did [with The Boy & The Dog], it is good for the pieces, but not the final product. I teach students to think how they can save time using AI—say, creating pre-composition thumbnails, or constructing some of the nominal, boring background elements.”

This parts-versus-whole philosophy was recently given legal consideration by the United States Copyright Office this past February. The ruling, one of the first related to AI-generated art ownership, granted the creator of the comic Zarya of the Dawn ownership of “parts” of her book—the images, created by Midjourney, were omitted, as they were not the product of “human authorship.”

“My approach with students is, they have to be introduced to this,” says Domingue. “We as artists and creators can’t be lazy anymore. We have to ask ourselves, ‘Can I do this better than AI?’ or ‘What can I offer that AI can’t?’”

Here lies the challenge for young artists.

First, smaller tasks generally assigned to entry level artists and interns. For example, creating social media graphics or writing clickbait listicles can now be more quickly and cheaply spit out using AI. This could make the barrier of entry into certain fields and companies more steep.

Another concern is exposure to these tools. A 20192020 State of Public Education in New Orleans report released by the Tulane University Cowen Institute revealed that more than 80 percent of public school students come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, nearly 20% of which lacked adequate internet access at home.

Working with AI is not only important for artists, but will increasingly become an important skill in the business world moving forward. Ensuring our future leaders and professionals are experienced in these technologies is vital.

“Artists and creatives who don’t figure out how to use AI to their advantage will get passed up by someone who does,” warns Domingue. “You can feel that things are changing, and I don’t know where they are going, but those who don’t have a good grasp on it will get squeezed out by this technology.”