A Celebration at HAREWOOD

A Washington Home for a Madison Wedding

ROBERT GROGG AND WALTER WASHINGTON

white house history quarterly 79

BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

they were an unlikely couple , Dolley and James, she a 24-year-old widow with a twoyear-old son, he a 43-year-old bachelor once jilted in love. She was outgoing and gregarious. He was shy. She stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall; he was 5 feet 4. She had been instructed at home and in Quaker schools.1 He was a graduate of the College of New Jersey (today’s Princeton University), an avid reader, and thoroughly absorbed in the life of the mind.2 He was, in fact, famous—a political leader recognized as “The Father of the Constitution” and author of the Bill of Rights, currently a represen tative from Virginia to the U.S. Congress. Yet they married.

Dolley Payne Todd and James Madison wed at Harewood, the Virginia home of Dolley’s sister Lucy Payne Washington and George Steptoe Washington, the son of President George Washington’s brother Samuel. Samuel had built Harewood in 1769–70 on property just west of the Virginia Blue Ridge where other Washington family members also built estates. Today Harewood is in West Virginia, just outside Charles Town. George Steptoe had inher ited it at age 10, on his father’s death. As a young man studying law in Philadelphia with Edmund

Randolph, he met and married Lucy Payne, Dolley’s younger sister. They eloped—he was 22 and she was 15—and returned to Harewood where they raised three sons. In September 1794 it was this family connection that brought Dolley Todd from Hanover County, Virginia, where she had been visiting with relatives, to wed James Madison, who traveled from Montpelier, his father’s Virginia estate.

Though Dolley—as she came to be called throughout her entire life—was born in North Carolina in 1768, her parents soon returned to Virginia, where they had both been raised. Her earliest memories dated from Hanover County, outside Richmond. In 1783 her parents moved to Philadelphia, the largest city in North America, the center of finance, and soon the temporary capital of the United States. It was also a city with a large Quaker population, and their faith was important to the Paynes. Despite John Payne’s efforts, his busi ness failed in 1789, and his wife, Mary Coles Payne, opened a boardinghouse to support her family. On January 7, 1790, daughter Dolley married John Todd Jr., a promising young Quaker lawyer, in the Pine Street Meeting House. Their Quaker marriage certificate read:

spread

A Washington family Bible set amid family heirlooms evokes the scene in 1794 when James and Dolley Madison were wed in this room at Harewood.

left James Madison (as portrayed by Charles Willson Peale, 1783) and Dolley Payne Todd Madison (c. 1805–10) were an unlikely couple.

white house history quarterly80

previous

LEFT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / RIGHT: YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY OPPOSITE: RICK FOSTER FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

Harewood, the Washington family home as it appears today. The stone house near Charles Town, West Virginia, was the site of the 1794 marriage of James and Dolley Madison. At the time of the marriage, Harewood was the home of Dolley Madison’s sister Lucy Payne Washington and her husband George Steptoe Washington. Washington died in 1809, leaving Lucy a widow with four children. The Madisons would later return Lucy’s favor by hosting her second marriage to Supreme Court Justice Thomas Todd at the White House in 1812. It was the first documented White House wedding.

white house history quarterly 81

and the said John Todd taking the said Dolly Payne by the hand did in a solemn manner openly declare that he took her the said Dolly Payne to be his wife promising with Divine assistance to be unto her a loving and faithful husband until death should separate them. And then in the same assembly the said Dolly Payne did in like manner declare that she took him the said John Todd to be her husband promising with Divine assistance to be unto him a loving and faithful wife until death should separate them.3

The Todds’ first child, John Payne Todd, was born two years later, and a second son, William Temple Todd, was born seventeen months after that. Little is known of their family life, but eigh teenth-century marriages were extremely pri vate.4 One of the very few extant signs of affection between them is a July 1793 letter in which Todd wrote, “I hope my dear Dolley is well & my sweet little Payne can lisp Mama in a stronger Voice than when his Papa left him.”5 John Todd’s law practice flourished, and in November 1791 the couple pur chased a substantial brick home on the corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets. Besides their small family, Dolley’s younger sister Anna lived in the house, as did several of Todd’s law clerks.6

The Todds’ world came to an end in early August 1793, when the first cases of yellow fever appeared in Philadelphia. Refugees from the slave revolts in Haiti arriving in East Coast ports may have brought mosquitoes with them. In the next three months, until the first frosts that would kill the mosquitoes, almost 10 percent of the city’s population (then about fifty thousand) died, an average of four hun dred every week. Medical knowledge was primitive, and no one had a scientific explanation for what was causing the disease. Likewise, treatment relied on bleeding and purging, both of which we now know only weakened patients. The sickness struck indiscriminately, and the only remedy that seemed to work was to leave the city. Although not under stood at the time, leaving was probably the best approach, for moving inland put distance between low-lying stagnant water along the river where the mosquitoes bred. As the number of deaths mount ed, John Todd took his wife and sons to the coun tryside, about 2 miles from the city center, and then returned to Philadelphia to nurse his parents, help others, and write wills.

In early October 1793 Dolley Todd wrote to her brother-in-law, James Todd:

Oh my dear Brother what a dread prospect has thy last Letter presented to me! A reveared Father in the Jaws of Death, & a Love’d Husband in perpetual danger—I have long wished for an oppertunity of writeing to thee & enquireing what we could do? I am almost destracted with distress & apprehension—is it two late for their removal? or can no interfearance of their Earthly friends rescue them from the general fate? I have repeatedly Entreated John to leave home from which we are now unavoidably Banished—but alass he cannot leave his Father.7

On October 2, probably about when this letter was written, Todd senior died, and ten days later his wife also died. Realizing that he was also ill, John Todd left Philadelphia to join his wife. He died October 24, the same day his and Dolley’s infant son, William, also died. Dolley, feverish and weak, survived and though exhausted was able to care for her two-year-old son, John Payne, and her 14-yearold sister, Anna. Within a few weeks frosts killed the mosquitoes, and the epidemic ended almost as suddenly as it had begun.

Dolley Todd had little time for grief, for absorb ing the impact—legal and logistical—of four deaths came with unimaginable burdens. Letters to her brother-in-law show a woman willing to confront the complexity of settling her husband’s and her in-laws’ estates, but she had little choice. James Todd must have suggested that John Todd’s library could be sold for ready cash. Dolley’s reply reveals her desire to protect her son and give him a legacy from his father:

I was hurt My dear Jamy that the Idea of his Library should occur as a proper source for raising money. Book’s from which he wished his Child improved, shall remain sacred, & I would feel the pinching hand of Poverty before I disposed of them. I have not time to say much but trust in Heaven ‘all will be rite’ & that our homes may yet afford us a plentiful assilum— with Love to you all. 8

She wrote again the next week “in order to ob tain some information concerning transactions in town. . . . I wrote thee some days ago, requesting

white house history quarterly82

a copy of the Will & the papers contain’d in the Trunk.”9 The letters continued through the winter, and in early March 1794 Dolley received an ac counting from James:

I herewith enclose the accot. of Marg’t Harveys receipts & expenditures while employed in our family, also the accot. of the Estate of my mother Mary Todd, and my accot. of the Estate of thy late husband. Thee will perceive that I have credited the Estate of Mary Todd with the whole of what was bequeathed to her altho’ I have not received from the Estate of my father any part of the £100 left in Cash. I have also credited the Estate of thy late husband with his full proportion of our mother’s Estate.10

So the estates were settled, and the young widow turned toward renting her house and soon to pre paring to pay attention to the congressman from Virginia.

James Madison was a truly distinguished fig ure. He had been active in political affairs since the early 1770s, starting with his local revolutionary committee of safety for Orange County, continu ing with the Continental Congress, and then with the Confederation Congress. He was one of the first to realize that the Articles of Confederation were too weak to channel the states into a union that would be greater than the sum of its parts. He was the author of the Virginia Plan that served as the point of discussion once the participants at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 realized they must come up with something new rather than merely “fixing” the Articles of Confederation. In support of the Constitution they drafted, Madison wrote twenty-nine of the eighty-five essays that came to be known as The Federalist Papers. In 1794 he was in Philadelphia as a congressman from Virginia, serving in the House of Representatives where he had advocated passage of the Bill of Rights. Serving in the Senate was his colleague Aaron Burr of New York, who had once lodged in Dolley Todd’s mother’s boardinghouse.11

In May 1794 Dolley Todd wrote an excited note to her friend Eliza Collins: “Dear Friend, thou must come to me. Aaron Burr says that the great little Madison has asked to be brought to see me this evening.”12 Nothing is known of that first meeting, but it must have been satisfactory, for on June 1, 1794, Dolley received a letter from a close friend, Catherine Thompson Coles:

Now for Madison he told me I might say what I please’d to you about him to begin, he thinks so much of you in the day that he has Lost his Tongue, at Night he Dreames of you & Starts in his Sleep a Calling on you to relieve his Flame for he Burns to such an excess that he will be shortly consumed & he hopes that your Heart will be callous to every other swain but himself he has Consented to every thing that I have wrote about him with Sparkling Eyes.13

By August, Dolley Todd had accepted James Madison’s proposal of marriage and received from him this reply: “I recd. some days ago your precious favor from Fredb. I can not express, but hope you will conceive the joy it gave me.”14 Early September still lacked a few weeks of being a year since John Todd’s death, and Quaker custom was to wait a year before remarriage. But with a suitor willing to take on a two-year-old boy, as well as a younger sister to protect, Dolley may have been willing to ignore Quaker tradition, especially since Madison was an Episcopalian and she would be read out of the meeting for marrying him in any case, as she was.

On Monday, September 15, 1794, Dolley Payne Todd and James Madison were wed in the pan eled drawing room at Harewood. The Reverend Alexander Balmain, rector of Christ Episcopal Church in nearby Winchester, performed the ceremony.15 His wife, Lucy Taylor, was a Madison cousin, and the event was a family affair. In atten dance were George and Lucy Washington, Harriot Washington (George Steptoe’s sister), Mary Payne (Dolley’s mother) and her children John, Anna, and Mary, and James Madison’s sister Fanny.16

The next day Dolley wrote to her friend Eliza:

And as a proof my dearest Eliza of that confidence & friendship which has never been interrupted between us I have stolen from the family to commune with you—to tell you in short, that in the cource of this day I give my Hand to the Man who of all other’s I most admire—You will not be at a loss to know who this is as I have been long ago gratify’d In havening your approbation—In this Union I have every thing that is soothing and greatful in prospect—& my little Payne will have a generous & tender protector.17

James Madison, too, wrote of his wedding to his friends. Henry Lee, known as “Light Horse Harry,”

white house history quarterly 83

replied, “I hear with real joy that you have joined the happy circle & that too in the happiest manner. To your lady present my most respectful congratu lations. She will soften I hope some of your political asperitys.”18

To Thomas Jefferson, Madison wrote: “I write at present from the seat of Mr. G. Washington of Berkeley,19 where, with a deduction of some visits, I have remained since the 15th. Ult: the epoch at which I had the happiness to accomplish the alli ance which I intimated to you I had been sometime soliciting.”20

To his father, he wrote: “On my arrival here I was able to urge so many conveniences in hastening the event which I solicited that it took place on the 15th. Ult.”21 Madison concluded his letter letting his father know that he, Dolley, Anna Payne, and Harriot Washington were visiting with his sister, Nelly Conway Hite, who lived at Belle Grove,22 south of Winchester, after spending one night with the Balmains in Winchester.

Dolley Payne Todd Madison, who had suffered so many losses, now had a new and enlarged fami ly. Neither she nor James could imagine or predict what lay ahead, but they must have sensed they would not lead ordinary lives. Through all the com ing years they remained devoted to one another. Because they were so seldom apart, only a few let ters remain to give insight into their forty-two-year marriage. But one, from Dolley to James in 1805, gives clues: “A few hours only have passed since you left me my beloved,” she wrote, “and I find nothing can releave the oppression of my mind by speaking to you in this only way.” She concludes, “Adieu, my beloved, our hearts understand each other.”23

HAREWOOD AND WASHINGTON FAMILY HOMES IN JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA

In what is today Jefferson County, West Virginia, there were once seven homes built by members of the Washington family. The fami ly’s interest in the area dates to the early surveys made in the Shenandoah Valley by the young George Washington for Thomas, Lord Fairfax, who had inherited more than 5 million acres be tween the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. The Washingtons were closely allied with Fairfax. George Washington’s older half-brother Lawrence married Anne Fairfax in 1743, and George was good friends with Anne’s brother George William and his wife Sally.24

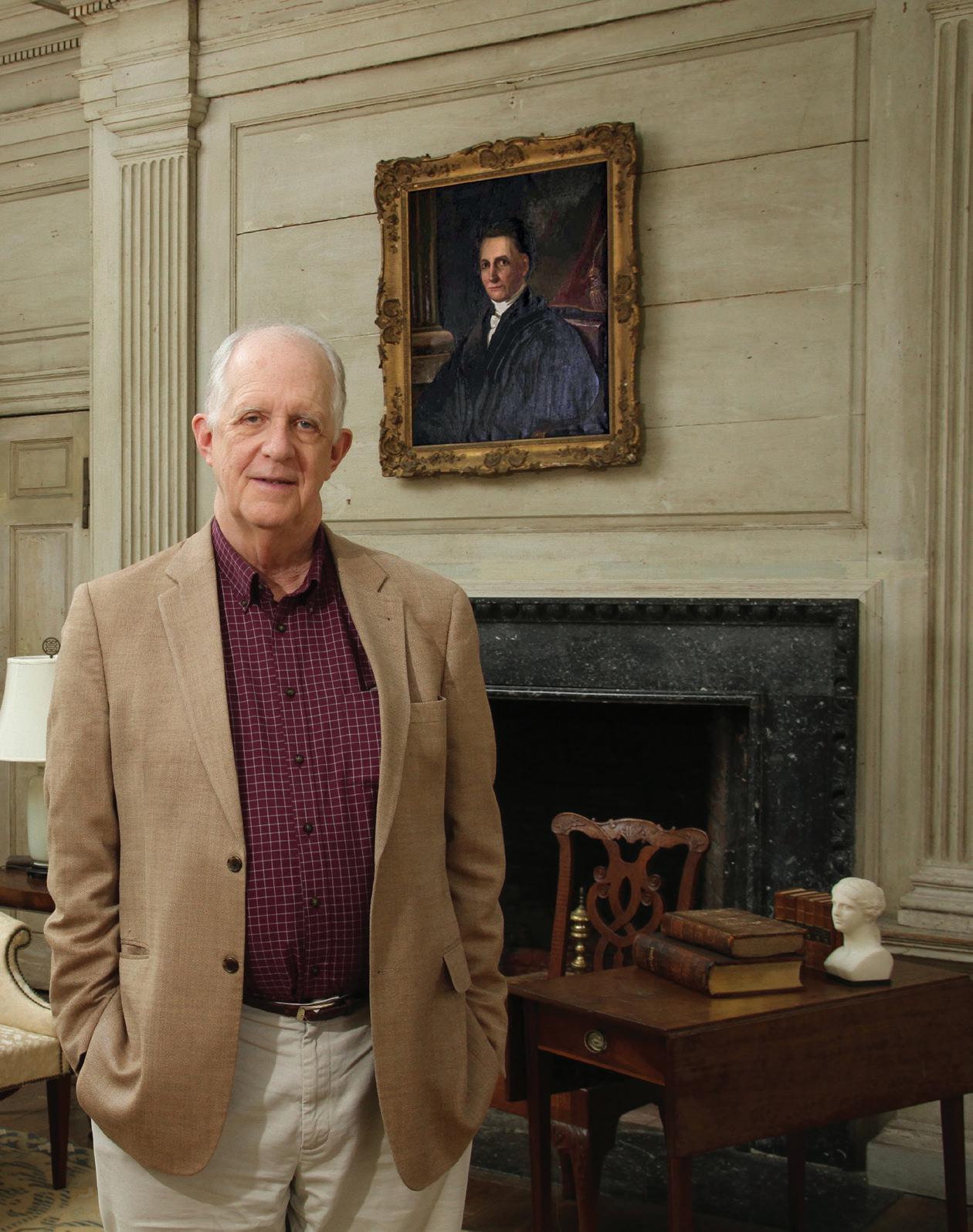

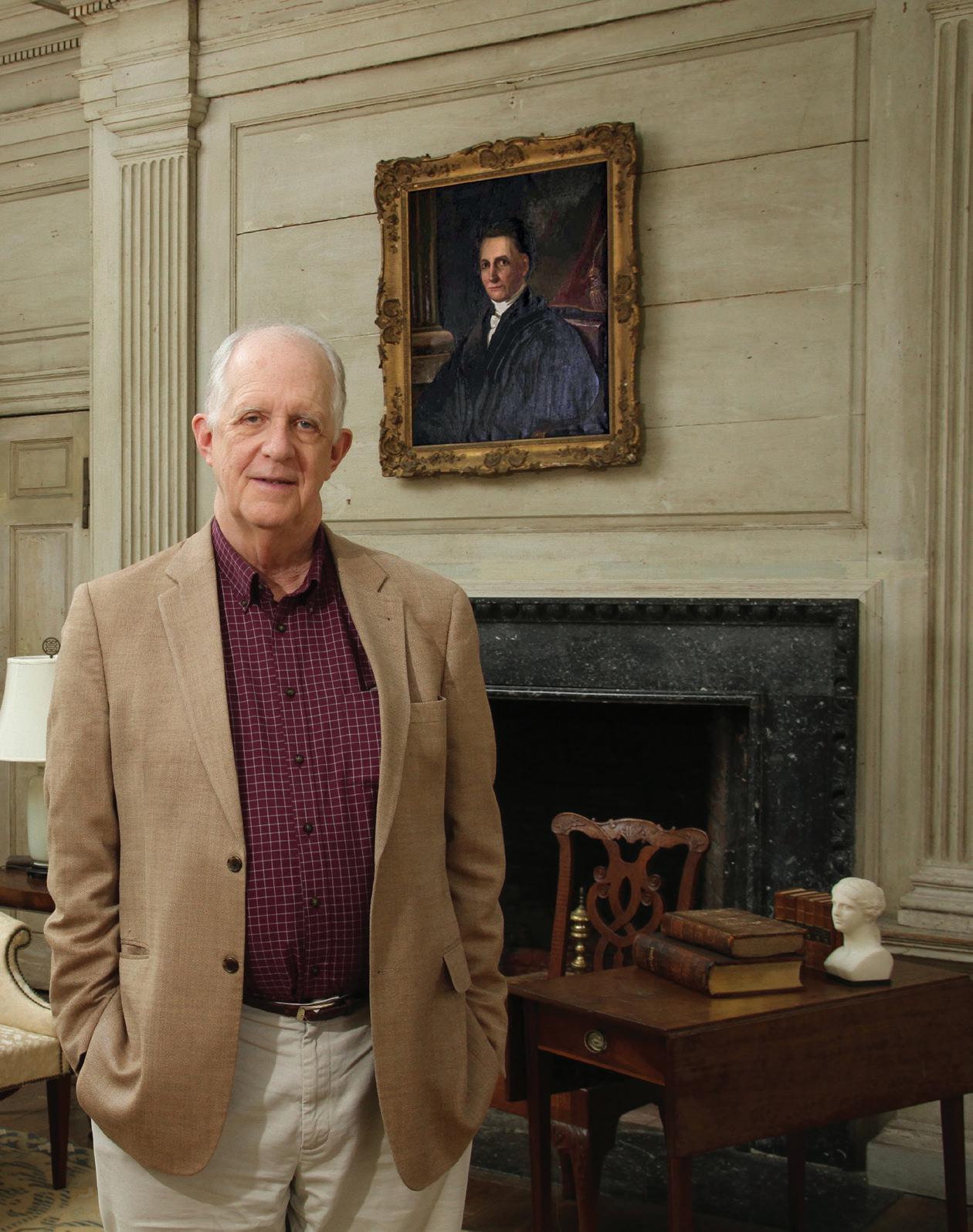

Walter Washington (above) reflects on scenes in his family home, preserved now for generations: “I’ve always liked the way the light comes into this room, and this picture (opposite) really captures that quality. The pianoforte was owned by Lucy Payne Washington. It was made in Vienna about 1800 by Andre Stein. We do not know how it arrived here, and it has not been played for years. The portrait above the piano is of Lucy, and John Drinker, who was a regional artist, painted it, probably in the late 1790s. The frame is not the original; it was replaced in the 1960s. The crack in the paneling behind the portrait happened when central heat was installed throughout the house in the 1960s. For a long time we had only one of the two chairs, the ones with the red seats seen here. But we found the second in the cellar, in total disrepair. It looked like it might have been broken in a bar fight. But now it has been repaired and sits here with its companion. The pair dates from about 1810. The floor is the original one laid down when the house was built. As far as I know it has never been refinished. As a child I remember watching my parents go over each board with steel wool to remove the grime. The job finished, they carefully waxed the wood, as so it remains.

white house history quarterly84

ABOVE: RICK FOSTER FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OPPOSITE: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

In describing this view, Walter Washington explains: “James and Dolley stood in front of this fireplace as the wedding service was read. The portrait over the fireplace is of Bushrod Washington, son of John Augustine Washington, and nephew of President George Washington. Bushrod Washington inherited Mount Vernon from his uncle and served as an associate justice on the United States Supreme Court, 1798–1829. Looking at this picture makes me realize that I live in a place that six generations of my family have called home, amidst all the things that they have acquired. The Bible on the table to the right of the mantel is a family Bible, but it is one of several. The books were bought by someone, I don’t know who and probably before the Civil War, and they have become part of the fabric of the place. The bust belonged to Patty Willis, my great-aunt. She was born and raised in Charles Town and was a member of the Provincetown Art Colony. She is the one who copied the portrait of Bushrod Washington that hangs over the fireplace.”

86

BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

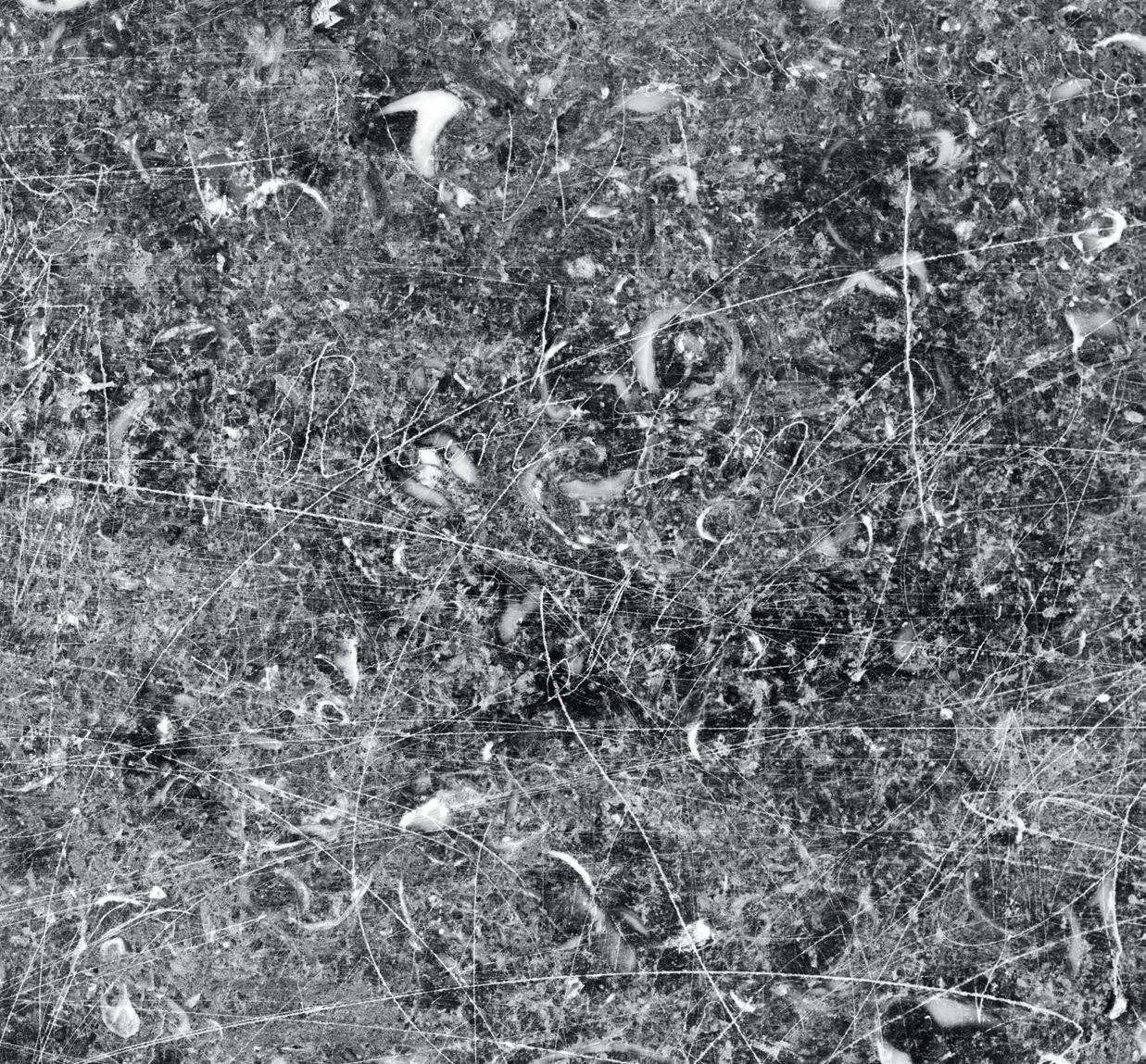

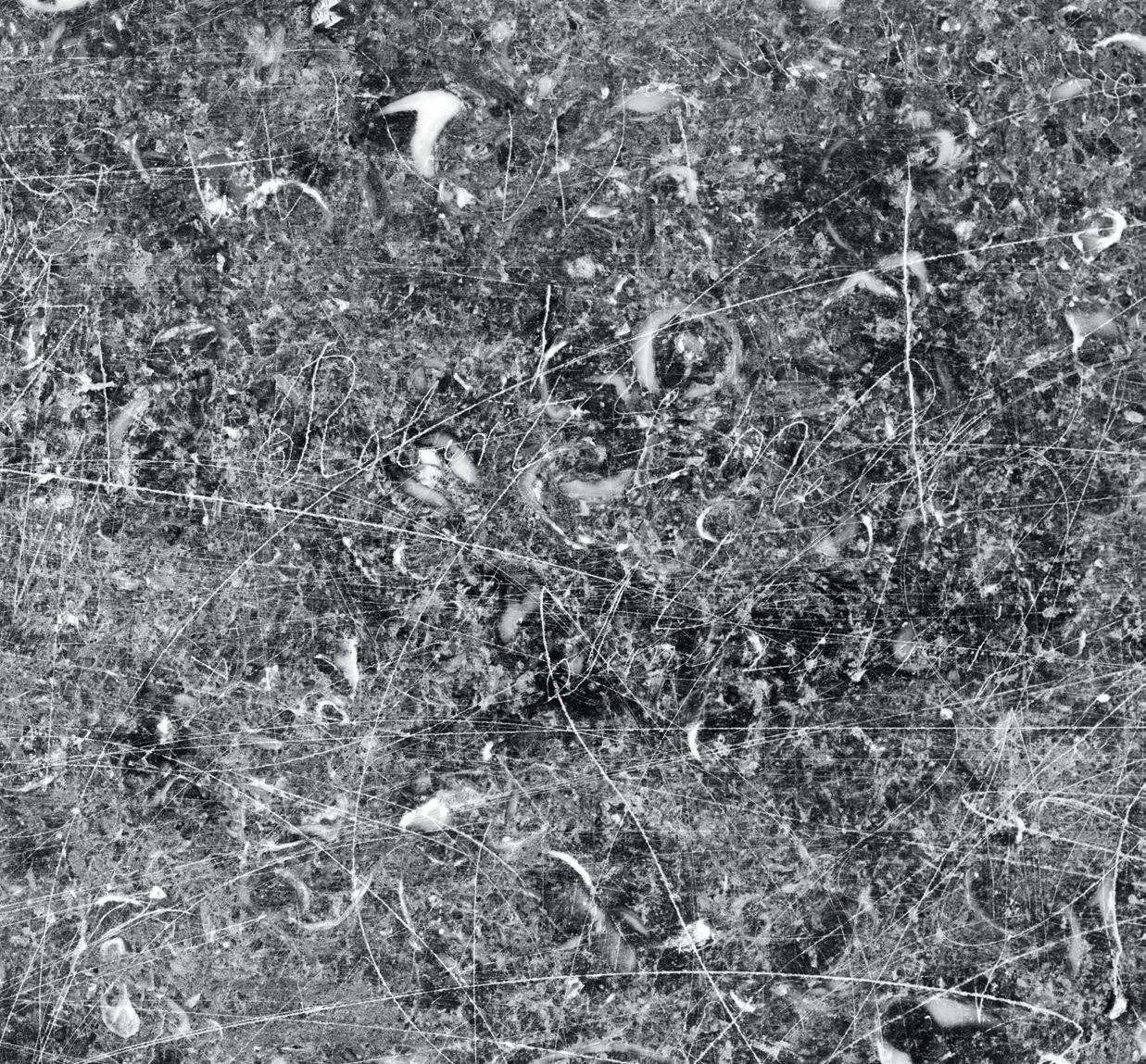

In telling the story of the fireplace mantel in the parlor where the Madisons were married, Walter Washington recalls that it “was a gift from Lafayette to George Washington. He gave it to Harewood, and it is believed that he gave a second Lafayette mantel to Fairfield in Clarke County, Virginia. Though that mantel is not there, a fragment has been found that matches the style of this one. Sir Desmond FitzGerald, an Irish Georgian expert, visited here once. When he saw the mantel, he exclaimed that it must have come from a quarry in Kilkenny, Ireland, owned by the Colles family. From the 1750s onward, the family quarried marble, fashioning the stone into fireplace mantels and sending them to North America. FitzGerald speculated that the Irish quarry was the origin of this mantel. In 1970 a cousin visiting from New Mexico, Kate Brown, happened to notice while looking closely at the mantel that you could make out names, bits of poems, dates, all scratched into the marble. No one had noticed this before or remembered hearing about it. In 1987 another cousin, Mikaela Bolek, spent time going over every inch and deciphering as she could of what had been written. She came up with a list of more than twenty names, several dates, and bits of poems or sayings.”

white house history quarterly88

“The chair is, I think,” says Walter Washington, “Chippendale, one of a set of six that George Washington bought for Mount Vernon. My greatgrandmother was visiting Mount Vernon when it still belonged to the family, and found this chair with the back broken out sitting on a pile of kindling. She rescued it, brought it back to Harewood, where she had it restored. The Roman numeral “III” is carved on bottom of the seat, marking it as the third chair of the set of six. “

white house history quarterly 89

ALL PHOTOS THIS SPREAD: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

The paneling in the parlor where the Madisons were married, remarkably, has not been painted for more than two hundred years. Walter Washington explains: “My parents sent off a sample of the paint to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and asked what the experts could tell. They concluded that the paint was the original and had never been painted over. What you see today is the original coat of paint put on in about 1770. Over the years, more than two hundred now, the paint has probably faded a lot. It might have been much, much brighter. It is amazing that the paneling in this room is so elaborate. When this house was built it was in the middle of nowhere. This was wilderness. This was the frontier. It is a mystery to me how such intricate and beautiful work was done.”

white house history quarterly90

BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

George Washington bought for himself some of the land he surveyed, while Lawrence Washington bought extensive tracts, and at his death left large holdings to his brothers, Samuel (who built Harewood, 1769–70), John Augustine, and Charles (who built Happy Retreat in 1780). Two of Samuel’s descendants built Cedar Lawn (1825) and Locust Hill (1840) on parts of the original Harewood tract. John Augustine’s grandson built Blakeley (1820) and Claymont (1820) on the land he in herited. Lewis Washington, a great-grandson of Washington’s older half-brother Augustine, lived at Beallair (before 1791). Besides these properties in today’s Jefferson County, a Washington cousin, Warner Washington, married to Hannah Fairfax, built Fairfield in adjacent Frederick County (to day Clarke County), Virginia, in 1768. Audley, also in Clarke County, was the home of Washington’s granddaughter, Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis. All are still standing with the exception of Locust Hill, destroyed by fire in 1973.25

The American architect John Ariss designed Harewood and Fairfield. Thomas Tileston Waterman, the early architectural historian who conducted studies for the Historic American Buildings Survey, says of Harewood that its “sim plicity and excellent scale endows it with great distinction. . . . It exemplifies the full traditional Virginia plan of a central hall with a single room on either side and end chimneys.”26 Of all the Washington homes, Harewood alone remains in the Washington family.

To visit is a privilege. On a sunny morning in the summer of 2017, Walter Washington, the five times great-grandson of Samuel Washington, welcomed a contingent from the White House Historical Association to let us see and photograph the room in which Dolley Todd and James Madison married, described by Waterman as “one of the best of its period in the country.”27 It is unchanged to this day, with the original paint, now a crackled grayish green, still on the walls.

NOTES

1. Conover Hunt-Jones, Dolley and the “great little Madison” (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Foundation, 1977), 7–8.

2. Ralph Ketchum, James Madison: A Biography (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 45–46.

3. Dolley Payne Todd, Marriage Certificate, January 7, 1790, in The Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Holly C. Shulman (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2004), http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu. Subsequent Dolley Madison letters are cited from this digital edition.

4. By contrast, more can be known of the marriage of Abigail and John Adams from an extensive correspondence over many years. J.C.A. Stagg, “Madison’s Courtship and Marriage, ca. 1 June–15 September 1794,” in The Papers of James Madison Digital Edition, ed. J.C.A. Stagg (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2010), http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu. Subsequent James Madison letters are cited from this digital edition.

5. John Todd Jr. to Dolly Payne Todd, July 30, 1793, in Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Shulman.

6. Hunt-Jones, Dolley and the “great little Madison,” 14.

7. Dolley Payne Todd to James Todd, October 1793, in Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Shulman.

8. Dolley Payne Todd to James Todd, October 28, 1793, in ibid.

9. Dolley Payne Todd to James Todd, October 31, 1793, in ibid.

10. James Todd to Dolley Payne Todd, March 9, 1794, in ibid.

11. Ketchum, James Madison, 378–79.

12. Dolley Payne Todd to Elizabeth Collins, May 1794, in Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Shulman.

13. Catharine Thompson Coles to Dolley Payne Todd, June 1, 1794, in ibid.

14. James Madison to Dolley Payne Todd, August 18, 1794, in ibid.

15. Ketchum, James Madison, 381–82.

16. Katharine L. Brown, Nancy T. Sorrells, and J. Susanne Simmons, The History of Christ Church, Frederick Parish, Winchester, 1745–2000 (Staunton, Va.: Lot’s Wife, 2001), 46.

17. Dolley Payne Todd Madison to Elizabeth Collins Lee, September 16, 1794, in Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Schulman.

18. Henry Lee to James Madison, September 23, 1794, in James Madison Digital Edition, ed. Stagg.

19. At the time of the Madisons’ marriage, Harewood was in Berkeley County, Virginia. Jefferson County was broken off from Berkeley and formed in 1801. “G. Washington” is George Steptoe Washington; the more famous “G. Washington” was very much still alive and president of the United States.

20. James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, October 5, 1794, in James Madison Digital Edition, ed. Stagg.

21. James Madison to James Madison Sr., October 5, 1794, in ibid.

22. Belle Grove was owned by Isaac Hite, a descendant of an early Shenandoah Valley settler. The manor house, extant today, was under construction at the time, and the Madisons stayed in Old Hall, no longer standing. The manor house was in the middle of an important Civil War battle in October 1864, the Battle of Cedar Creek, and is today a part of Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park.

23. Dolley Payne Todd Madison to James Madison, October 23, 1805, in Dolley Madison Digital Edition, ed. Shulman.

24. Lord Fairfax was the only peer to remain in America at the outbreak of the Revolution. Virginia confiscated his holdings, and he lived out his days in the Shenandoah Valley, dying a few months after the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781. He is buried in the courtyard of Christ Church, Winchester.

25. For more on the Washington homes and families, see The Washington Homes of Jefferson County, West Virginia (n.p.: Jefferson County Historical Society, 1975); James H. Johnston, “Lincoln and the Washingtons,” White House History, no. 36 (Fall–Winter 2014): 102–15.

26. Thomas Tileston Waterman, The Mansions of Virginia, 1706–1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1946), 326–30.

27. Ibid., 326.

white house history quarterly 91

presidential sites

presidential sites