7 minute read

Ashes to light

Rachel Mulligan, a local stained glass artist, has joined forces with the School and volunteers to restore beautifully crafted fragments of our history

Advertisement

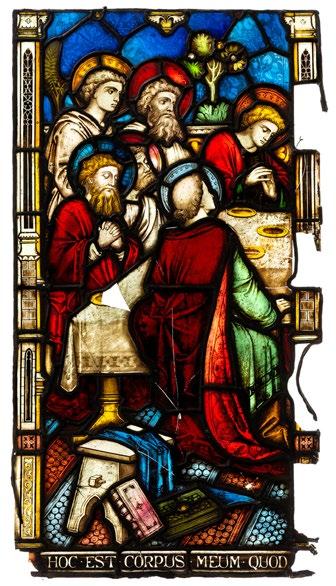

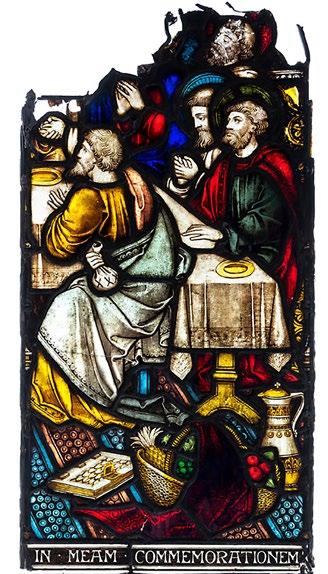

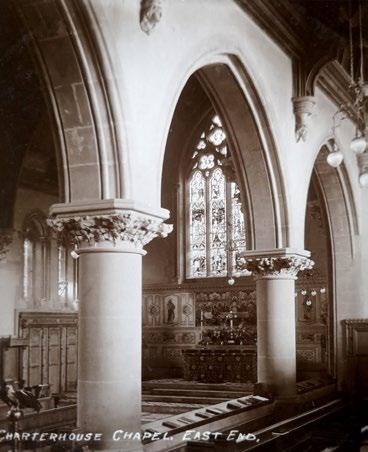

The exquisite stained glass windows of the original Charterhouse Chapel in Godalming must have made for a splendid spectacle when they were first unveiled in 1874. They were created by a renowned British glass manufacturer and depicted biblical panoramas each of which stretched across 18 windows – with a stunning rose window at the east end donated by Queen Victoria in memory of her beloved Prince Albert. Many beaks and pupils must have gazed at them in wonder in the years that followed. Once the much larger Memorial Chapel was consecrated, however, the Old Chapel was converted into a Music School, with the stained-glass panoramas removed in 1939. Queen Victoria’s

window remained, although it is covered up on the inside of the building and can only be seen externally from Gownboys’ private side.

Then there was a terrible accident. In the mid 70s, the barn storing the glass burnt down, melting some of the lead and causing soot damage. An enterprising beak (Mr Clive Carter, BH65–96) and his archive volunteers researched the history of the glass, cleaned as much as they could, and put it on exhibition in 1976, appealing for it to be properly restored. The exhibition showed off the glass to good effect but, unfortunately, no money was available for repairs, and the panels went back into storage, some of them suffering further damage during a second fire in 2008.

Dr Ernst Zillekens (BH79–17) made another rescue attempt by approaching stained glass specialists for advice, only to be told that the glass was beyond repair. Miraculously, when all hope had been lost, a local stained glass artist called Rachel Mulligan proposed a rescue plan. She believed that some of the glass was of sufficiently good quality to be reinstated into the fabric of Charterhouse and that even the badly damaged fragments could be repurposed into new works of art.

A labour-intensive cleaning programme began, as more than 80 panels were gently cleaned. The process was supervised by Rachel and other artists from the Surrey Glass Easel Collective, but much of the work was carried out by volunteers of all ages, ranging from pupils, parents and staff to local ‘University of the Third Age’ members. The cleaned glass was then photographed

by local photographer Mark Melling to create a full record.

Rachel Mulligan and the Surrey Glass Easel Collective are also repurposing fragments into unique stained glass artworks to help fund the expense of rehousing the larger panels. “We have learnt from the masters and it has been a real privilege to help give the art a new lease of life,” says Rachel. “I would love to see some of it back in its original location in the Founders’ Chapel and given a contemporary twist.”

The idea of buying a unique piece of Charterhouse history has caught on. Mark Everett (B77) was one of the pupils who displayed the windows in 1976 and is thrilled to have a piece of the historic glass. “I’ve bought a small piece and they have done a great job,” he says. “It’s colourful, interesting and done to a very high standard.” b

Above: Rachel running one of the glass cleaning sessions. Right: The glass in the Old Chapel, photographed before the fire

F A catalogue of repurposed glass for sale can be found on the School website: www.charterhouse.org.uk/ foundation/glass-restoration

OC ORIGINALS

Mountaineer, Scholar, Poet Wilfrid Noyce (W1936; BH50–61)

Wilfrid Noyce

Our quiet hero of the mountains

He prepared for the first successful attempt to climb Mount Everest by pushing his son up Rackets Court Hill in a pram. Wilfrid Noyce was a true Carthusian hero who achieved much before losing his life to the sport he loved

Wilfrid Noyce combined academic excellence with charm, strength, skill and a strong sense of public service. Following in the footsteps of his Brooke Hall predecessor George Mallory (BH1920–21), he was part of the successful British mountaineering team that finally conquered Everest in 1953, and is commemorated (with George) at the west entrance of Charterhouse's South African Cloister.

Cuthbert Wilfrid Francis Noyce (W36; BH50–61) was born at Simla, in India, on 31 December 1917, the eldest child of Sir Frank Noyce, an Indian government civil servant, and Enid Noyce. He came to Charterhouse with a junior scholarship, joining Weekites in OQ1931, then attained a senior scholarship and became Head of School. His main sport at School was cross-country, but he learnt to climb with his mentor John Menlove Edwards in the holidays and fell in love with mountaineering.

After Charterhouse

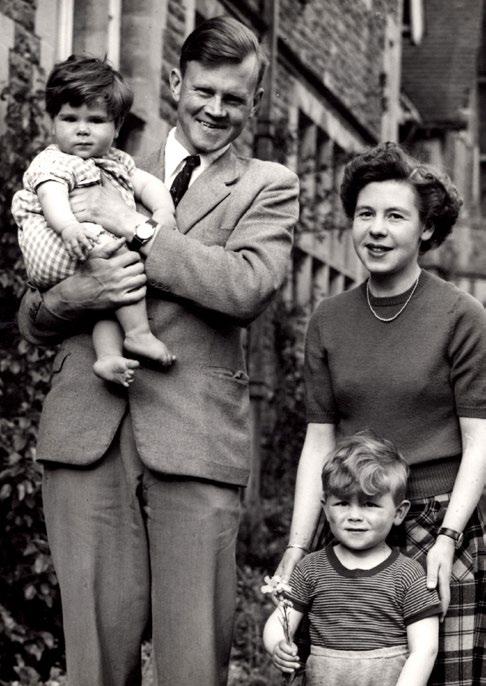

Noyce then went to King’s College, Cambridge, as a scholar in 1936, graduating with a First in Modern Languages. He also continued to climb, surviving a serious accident on Scafell in 1937, which necessitated plastic surgery to his face. During WWII he volunteered with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, then joined up as a Private in the Welsh Guards. Following this, he spent four years in India, first as an Intelligence Officer and then as chief instructor at the aircrew mountain centre in Kashmir. On his return to England he taught Classics and French at Malvern College where, in August 1950, he married Rosemary Davies. The newly married couple moved to Charterhouse, where Noyce taught French. He was allowed leave of absence for mountaineering trips and he also found time for writing, ranging from autobiography to poetry, novels, magazine articles and climbing guides.

Noyce’s style in the hashroom was quiet and scholarly, and he was always modest about his achievements. He gave

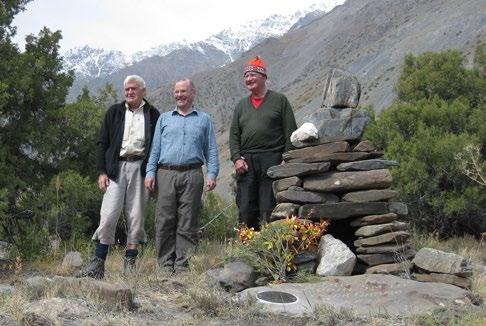

Main: Wilf Noyce (centre) with a group of King’s Scouts in 1954. Left: With his family in 1955. Above: The Wilf Noyce Memorial at Mount Garmo

his time unstintingly to the Charterhouse Scouts and founded the Mallory group. He also served on Godalming Borough Council, with a particular interest in youth work and libraries. The Godalming youth centre is still named the Wilfrid Noyce Centre in his honour. The annually awarded Wilfrid Noyce Personal Achievement Trophy was donated by Godalming & District Youth Committee to commemorate his part in the ascent of Everest.

Tackling Everest

Noyce was invited to join the 1953 British Everest expedition. The School was happy to grant a sabbatical and he embarked on a rigorous training programme, which included regularly pushing his baby son Michael up Rackets Court Hill in a pram weighed down with rocks. The team left Kathmandu for Mount Everest on 10 March 1953, arriving at Base Camp on 12 April. Noyce and Sherpa Annulla were the first to reach South Col on 21 May. This was a critical breakthrough because, at a point where the team were all doubting their ability to reach the summit, the sight of Noyce and Annulla on the Col gave them fresh courage.

The expedition leader, Colonel John Hunt, planned three attempts on the summit: the first assault, by Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, came within 300 feet but they were forced to turn back. On 27 May, the second assault, by Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, became the first successful ascent of Everest.

Had they failed, Noyce and Hunt would have made the third assault. Far from being disappointed, Noyce celebrated the team’s success. He greeted Hillary and Tenzing with hot tea as they descended to the camp

and rushed out with sleeping bags to signal the good news to those below.

Despite his natural inclination to slip quietly back into teaching without any fuss, he was given a hero’s welcome on his reappearance at Charterhouse. Andrew Douglas Bate (P54) recalled, “It was a fine afternoon for cricket and I was keeping out of trouble away in the deep field. Suddenly in the distance, I heard the sound of cheering. It grew louder and louder and I could see Wilf Noyce walking down the avenue. He seemed a little embarrassed by the noise as he walked with his wife and wheeled his baby in the pram. As he went by, we all cheered. He waved thank you and when he had passed we took up the game again.” (The Carthusian, Dec 1962).

Noyce left the School in CQ1961 to focus on his writing career, but was persuaded by John Hunt to join a British–Soviet expedition to the Pamirs. The divergent expectations and techniques of the two nationalities caused friction during the expedition, and perhaps contributed to the circumstances of Noyce’s death. After a gruelling ascent of Mount Garmo on 24 July it was decided to place Noyce and 23-year-old Robin Smith in the lead while the Russians stopped to put on their crampons. Noyce and Smith were roped together. The two men slipped and fell 2,000 feet into a gully. They were buried in the glacier where they fell and a memorial to them was built at the base camp overlooking the glacier. b