WE CAN'T SORT THIS OUT IN SILOS

Published by Riverford Organic Farmers SUSTAINABLE FOOD AND ETHICAL BUSINESS

ISSUE 12 | AUTUMN 2023

Meaden on ethical business,

and

THE FAIRNESS ISSUE | Food and class | Supply chains | Seasonal workers PLUS Wicked Leeks turns five

Deborah

climate

confidence.

Wicked Leeks is like a

of fresh

breath

air – opening minds to the idea of a truly better food system and sharing practical, inspiring examples of how it can be done.

The magazine for ethical eaters. News | Interviews | Ethical living | Giveaways | A friendly reader community Scan forafreeweekly edition

Vicki Hird, Wicked Leeks reader and head of farming at campaign group Sustain

Wash

01803 227416

wickedleeks@riverford.co.uk

Editor: Nina Pullman

Design: Chanti Woolner

Sub-editor: Ellen Warrell

Community: Hannah Neville Green

Contributors:

Fairness might seem an abstract concept, but this year it has turned into a hard reality for many farmers. It’s hard to explain the rising food prices on shelves alongside low or flat prices going back to farmers, but it’s something that is causing many to give up, sell up or intensify (pages 4-5).

FIND US ONLINE

wickedleeks.com

@wickedleeksmag

#WickedLeeks

While the supermarkets undeniably play a role, the bigger picture is that there is no real champion for food within government; someone who sees the links between food, health, climate change, farmer livelihoods, food security and trade deals, and can steer us to a sustainable food future. Elsewhere this issue, we hear what fairness means to others involved in food – after all, there’s also the pickers, the retailers and us, the eaters. Read pages 16-19 for more on that. We also hear about fairness in food culture, where middle-class produce is valued more highly than food traditions from more traditionally

working-class areas (pages 6-7). An ethical approach to business has been one of the overriding themes in the career of our cover star, Dragon’s Den stalwart and investor Deborah Meaden. She talks of her hopes and fears around climate change, whether big business can ever be green and where her confidence came from, in an exclusive interview on pages 10-15.

Excitingly, Wicked Leeks turns five this autumn. To celebrate, we wanted to showcase our brilliant, engaged and inspiring reader community who have been with us from the start. Read our selection of nominations for your food and farming heroes on pages 24-25, perhaps while enjoying a slice of our very special Wicked Leeks’ birthday cake (page 27). Here’s to you!

Nina Pullman Editor, Wicked Leeks @nina_pullman

Read on screen: www.wickedleeks. com/magazines

Printed by: Walstead United Kingdom, 109-123, Clifton Street, Shoreditch, London, EC2A 4LD.

Bob Andrew, Victoria Holmes, Martin Ellis, Emily Muddeman, Jack Thompson, Abi Williams, Poppy Okotcha, Dide Tengiz, Nathalie Lees Wicked Leeks

Please pass on or recycle this magazine once you’ve finished with it.

Dragon's Den star Deborah Meaden on how to balance business with the environment and her worries we won't act on climate change in time.

Food columnist Felicity Cloake on the hierarchy in food traditions and why some are disappearing. P6-7.

Investigative journalist Emiliano Mellino on how he uncovered exploitation of seasonal workers. P9.

Wicked Leeks magazine is published by Riverford Organic Farmers.

TQ11 0JU.

Farm, Buckfastleigh, Devon,

on 100%

FSC

paper,

is

magazine is printed

recycled

certified

meaning it

harvested from sustainable forestry.

CONTENTS & CONTRIBUTORS / ISSUE 12 NEWS / 4-5 OPINION / 6-9 FEATURES / 10-25 LIFESTYLE / 26-35

Welcome

@blewinbell | 10 Aug

Community

Most read on wickedleeks.com:

1 Plant milks: what's the healthiest?

2 Recipes for pickled veg

3 How to make elderflower cordial

4 Glyphosate use rises

Follow us: @wickedleeksmag on Twitter and Instagram

If one were looking for a ray of hope, what crops can we bring into the UK system through agroforestry?

@suepritch | 14 Aug

Our @FFC_Commission research with citizens shows that they want and expect governments to regulate businesses, not expect consumers to fix a structural problem with their shopping choices.

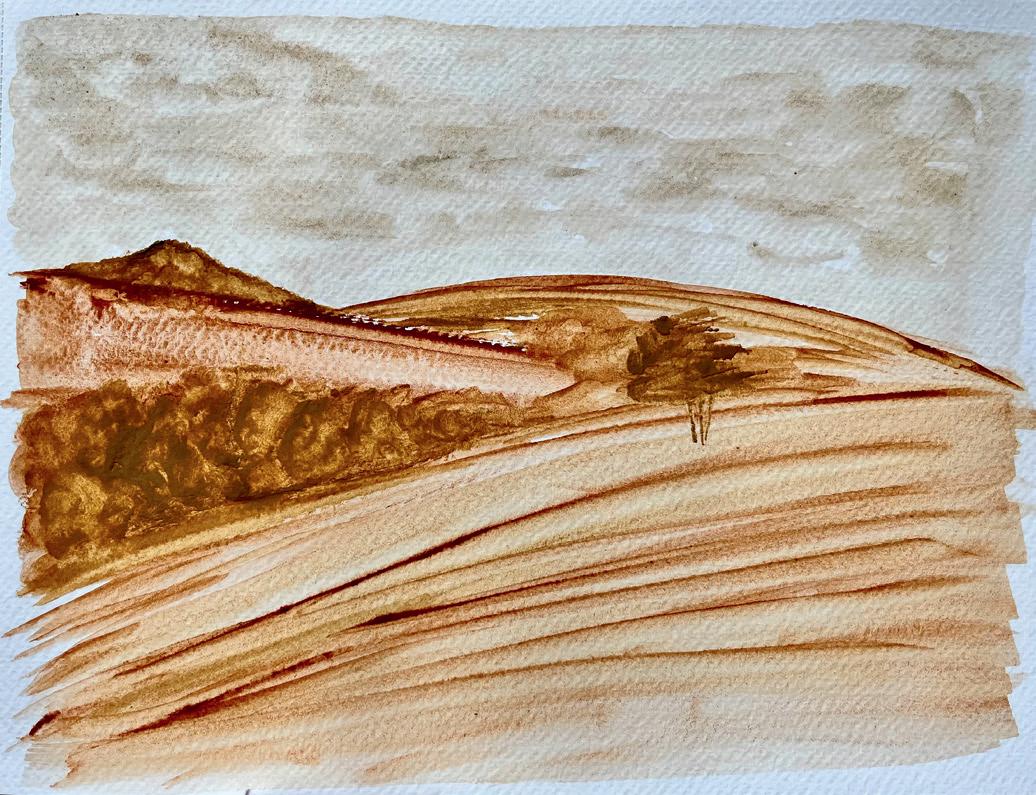

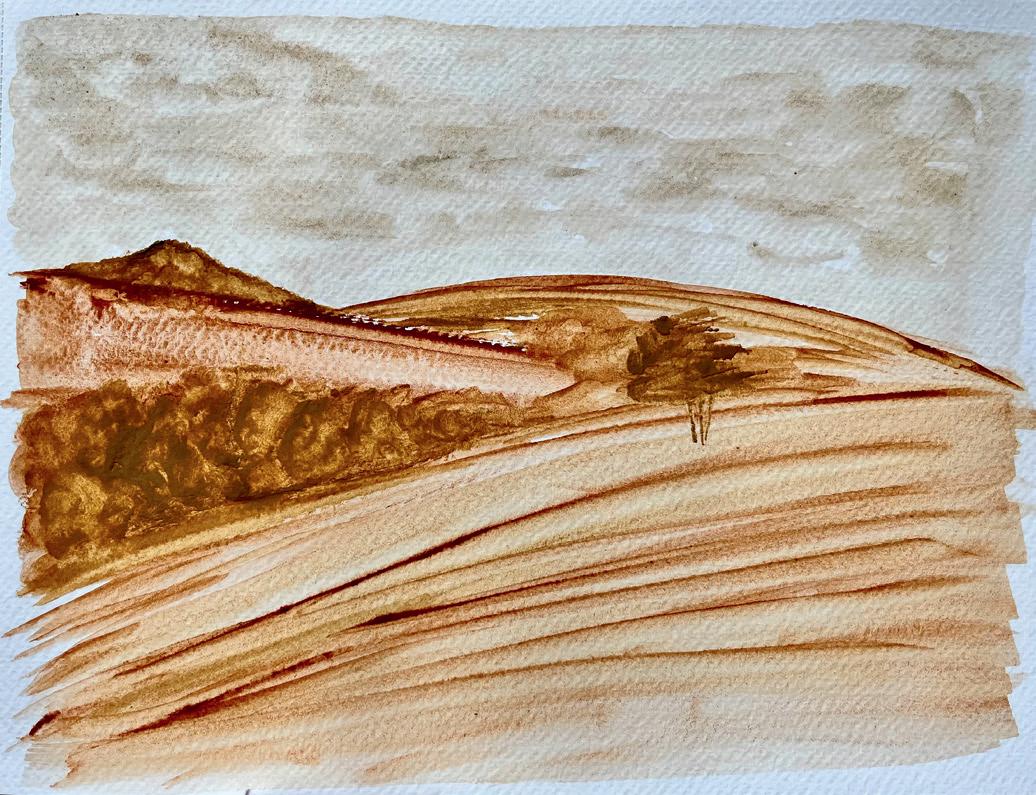

PIC OF THE CROPS

A field of organic artichokes goes to seed in Devon.

STAR LETTER

As the daughter of a 'small' farmer in the UK, my heart goes out to those suffering the loss of crops and livelihood every time you share something like this. Thank you for maintaining a sense of reality, a sense of what it really means to be part of the communities and families whose work is to provide us with our food.

Julie H

NEWS BY NUMBERS

Reservoirs in Spain’s Malaga region, which supplies the UK with key fruit and veg, were at eight per cent capacity over summer due to a prolonged drought.

Join the conversation at wickedleeks.com

Pressure builds as farmers struggle to survive

By Nina Pullman

Pressure is building on supermarkets and the government to find a way to balance rising costs, food prices and food security after multiple reports of UK farmers giving up in berries, apples, eggs and dairy.

Throughout the year, there have been stories of farmers struggling to make their businesses viable, many citing low or flat returns from supermarkets. In apples, trade body British Apples and Pears said growers had cancelled orders for new trees, while apple grower Paul Ward told Wicked Leeks that many around him in Kent are selling orchards to developers.

In berries, strawberry prices went up by an average of 11 per cent last year, while growers reported that their prices from supermarkets have not increased, and said they are buying fewer plants for

next season as a result. British blueberry growers said they are also giving up or reducing their acreage as they're not able to compete with cheaper Peruvian exports.

An investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority recently found supermarkets are “not profiteering” from food inflation. Morrisons and Tesco have also both announced they will pay millions to farmers to help cover costs this year. But speaking to the BBC’s Farming Today programme, trade journalist Kevin White said: “It’s good PR but the question is why weren’t you paying your producers a fair price previously, particularly in eggs.” In dairy, the Food Ethics Council (FEC) said it has heard reports of farmers leaving organic farming to focus on intensification and higher yields to cover low prices. Alongside this, the FEC said farmers have reported bullying tactics by milk processors (see page 8).

Pictured: Apple growers are selling up.

The UK is only around 54 per cent self sufficient in food, according to a new report, which warned that shocks to international trade and Brexit have exposed the vulnerabilities in our food supply. [Source: Efra]

It comes as a new report by the cross party committee for environment, food and rural affairs (Efra) warned that the government’s approach to food is “incoherent” and does not take into consideration the difficulties faced by farmers, or the cost of poor diets to the NHS. Chair of the committee, Sir Robert Goodwill, said: “Food security matters to us all. It is vital to farmers; it is vital for every citizen to have a square meal at a reasonable price. But surprisingly, the government does not appear to be taking this very basic matter anywhere near seriously enough.”

Elsewhere, a summer of extreme heat and drought in Spain and erratic weather across Europe has served as a reminder of the disruption to supply chains as climate change takes hold. Writing recently, founder of Riverford, Guy Singh-Watson, said: "Rather than assuming that we can buy our way to food security in a fragile global market, we need to invest in the infrastructure that will reduce the disruption ahead."

Others are hopeful that the impact on British farmers and the issues affecting global food will start to prompt action. Head of farming at campaign group Sustain, Vicki Hird, said: "The good news is that a growing body of evidence, and some better food traders, are sparking MP inquiries and the media spotlight on this hidden but harmful set up. For us to have a resilient, healthy, and fair UK food system, adaptable to the climate challenges ahead, this has to change."

Since 1990, average dairy herd sizes in the UK have doubled as farmers have intensified to cope with low milk prices. [Source: Food Ethics Council]

Unique children's hospital to put food at heart of mental and physical health

Aunique children's hospital in Cambridgeshire will put food at the heart of mental and physical health, with eating together, sourcing local food and reducing waste to be prioritised.

After hosting a unique 'Food, With Care' conference in January 2022, the Cambridge Children’s Hospital has unveiled plans for better dining spaces for patients, families and staff within the hospital, to encourage a healthy relationship with food, a focus on cultural significance and how to source sustainable food, with farmers including Sarah Langford

involved in the wider project team.

“I think that Western society has a tendency to separate the mind from the body, and, when it comes to health, to medicalise food and talk about it only in terms of nutrients and calories,” said senior research assistant, Elena Neri.

“This is the first time that people from completely different backgrounds and expertise are coming together to create a food vision that really thinks of food from a holistic perspective, giving due importance to the social, cultural, environmental and educational dimensions of eating.”

'Treat workers fairly and they'll return'

The government could help stop abuse of seasonal workers and prevent illegal brokers scamming them for fees by providing more information and licensed recruiters.

That’s according to a new report using testimonies from seasonal workers on UK farms, and analysis by the New Economics Foundation and other partners, which has uncovered how illegal brokers are charging seasonal workers thousands of pounds to come to the UK. The workers are then open to exploitative working conditions to pay back the debt, accepting long hours and abuse.

Fruit and veg growing in the UK heavily relies on seasonal workers, who come on a government visa called the Seasonal Worker Scheme. But there is no page of licensed operators on the government website, with many workers turning to ads on TikTok or Facebook to find out how to apply, where they often encounter illegal brokers.

“If the system is fair and clear, workers will come to the UK with a fresh mind, a positive attitude, contribute to the economy and solve the problems of food and labour shortages. And

they will return as well, reliable for all parties. We have to look after labour,” a Nepali seasonal worker told the report, which was compiled by the Landworkers’ Alliance. Report coauthor and researcher at the Open University, Clark McAllister, said: "Migrant workers in the agricultural sector face extreme exploitation. With widespread scams and fees plaguing the recruitment process for the Seasonal Worker Visa, many workers arrive in situations of debtbondage.” (See pages 9 and 19 for more).

NEWS ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 5

Above: The UK is reliant on seasonal workers.

OPINION 6 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

If there's been a local food revolution, it's been a distinctly middleclass affair.

On food and class

FELICITY CLOAKE

Food writer and author of Red Sauce, Brown Sauce @felicitycloake

My smallish local supermarket sells five types of brioche, four of ciabatta and precisely zero varieties of cottage loaf, stottie or tattie scone. Glossy food magazines endlessly romanticise the cucina povera of Italy or Spain and the vibrant street food of Asia, but rarely mention the pleasures of a hot pork pie and peas, a pillowy chip butty or vinegary cone of whelks – or indeed almost any of the regional specialities I enjoyed so much while travelling around Britain by bike for my last book, Red Sauce, Brown Sauce .

If there’s been a local food revolution in this country in the last few decades, it’s been a distinctly middle-class affair. The media rejoices in a £24 plate of faggots at London restaurant St John, but shrinks from any mention of the rough-hewn versions in high street butchers, let alone the £1 boxes of Mr Brain’s in the supermarket freezer.

For all the brilliant new bakeries in my north London neighbourhood, not one offers a lurid pink slab of Tottenham cake, the traditional local delicacy from this area. A plaintive recent request on the community app NextDoor asked for tip offs on “proper jam doughnuts for sale… [I’ve seen] cronuts, yes... cinnamon buns, yes... but I’m dying for an old-school jam doughnut." Meanwhile,

following the closure of our last pie and mash shop, my neighbour orders in bulk from Essex, filling her freezer to justify the delivery charge.

In the words of Joni Mitchell, you don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone – and if such traditionally working-class foods become so rare, or pricey, that few can access them, they’re as good as dead anyway. Sometimes, as with 'crappit heid' (boiled fish heads stuffed with oats), popular tastes have moved on; occasionally, as with jellied eels, sustainability issues have hastened the decline. But often it’s lack of availability that’s the problem; something which, of course, proves a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When real cider isn’t on offer in the local pub, and kippers have vanished from the supermarket fish counter, such things inevitably become a niche taste, available only to those with the time, or means, to visit specialist retailers.

You only have to remember the general hilarity earlier in the year at the idea we should be eating more turnips, often from pundits who were happy to admit they’d never even tried one, to see how proudly distanced we are from many of the once common foodstuffs that can be produced at the least environmental and financial cost in this country. Yes, the vegetable I know as swede is still commonly paired with haggis in Scotland, and you can find turnips on the menu at a few high-end British places – but it’s not a revolution if it doesn’t involve everyone.

Across the Channel, peasant dishes like garbure (ham and veg stew) or choucroute (sauerkraut with sausages) are considered just as much part of the national cultural patrimony as truffles or foie gras, and celebrated accordingly. Yet here we prefer to revel in the notion that our own fish and chips or fry ups are “disgusting” (as reported gleefully by outlets including the Metro and the Independent ), while happily jumping on any opportunity to mangle someone else’s cuisine instead.

Our food culture is, and always has been, enriched by change and outside influence – but if we don’t take our own modest culinary heritage seriously, what hope have we of truly understanding, and thus valuing, anyone else’s? Good British food should be accessible to everyone. And that includes proper jam doughnuts.

OPINION ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 7

Above: Tottenham cakes are a traditional north London bake, now rarely sold.

Headshot credit: Samuel Goldsmith

What's going on in dairy?

As the cost of milk falls in supermarkets, dairy farmers are bracing themselves for another tough year, with some deciding to pack up altogether. You may have heard of some dairy herds going up for sale, or rumours of milk prices being unsustainable. But when it’s still such a household staple, what exactly is going on in dairy?

While many are feeling overwhelmed trying to stay financially afloat, there is real appetite for change in the sector – but this needs to start with a fair deal for farmers.

Over the past three decades, the UK dairy industry has become bigger, more ‘efficient’ and more connected to the global marketplace. These changes have pushed many UK dairy farmers onto a treadmill of intensification, where stepping off can seem near impossible. Since 1990, average herd sizes have doubled and since 1975, milk yield per cow has increased by 100 per cent. Soaring input costs alongside limited increases in farmgate milk prices have pushed many small-scale farms out of production and others onto a pathway focused on increasing yield, rather than quality. This has had a major knock-on effect

for animal welfare, the environment and the physical and mental health of farmers and farm workers themselves.

Dairy farmers are now leaving the industry – in the past 25 years, producer numbers have dropped by two thirds. Data is yet to be published, but we have also heard concerns that some organic dairy farmers are either quitting altogether or converting back to conventional dairy systems.

Alongside the pressures to ‘get big or get out’, relationships between farmers and some processors and retailers have become increasingly strained, underpinned by unfair

contracts and power imbalances within the supply chain. The Food Ethics Council has heard from dairy farmers that were subject to bullying practices and given a matter of minutes to sign a new contract. Other issues are around exclusivity clauses preventing farmers from selling milk to other buyers, including their local communities. Milk prices are often dictated by processors with less than a week’s notice, and some farmers have to give 12 months’ notice to end a contract. With limited routes to market, farmers often have little choice in who they can sell their milk to, giving the power to buyers to call the shots.

Ensuring farmers are treated fairly can help accelerate a sustainable transition, by giving them time for peer-to-peer learning and confidence that changing their businesses will be rewarded. Meaningful change will only occur with improved communication, trust and transparency across the supply chain, as well as a rebalancing of risk.

Contract regulations have recently been in the spotlight as one solution, with the government announcing that there will be a new Dairy Code of Conduct. Although long overdue, this code will act as an important

OPINION 8 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

ABI WILLIAMS Project lead for the Food Ethics Council dairy project

Many UK dairy farmers have been pushed onto a treadmill of intensification.

signal to farmers they are not alone on the journey to better dairy.

Other changes needed include ensuring a fair price for milk, funding that supports nature-friendly farming, more opportunities for farmers to connect with the public, a marketplace that values milk as more than a commodity, plus more local public procurement opportunities.

Despite the pressures those in the sector are under, there are examples that we can take hope and inspiration from. For example, the rise in successful cow-with-calf systems, the creativity of farmers selling via milk vending machines and converted shipping containers, a growing interest in the use of regenerative systems and more processors explicitly focused on collaboration and fair purchasing practices. The future for dairy is far from black and white.

Seasonal workers deserve fair treatment

few journalists have. We invested that time in finding workers and making sure they trusted us enough to share their stories.

EMILIANO MELLINO Journalist for The Bureau of Investigative Journalism @Mellino

Iam beyond shocked at the normalised exploitation.” This is what Sybil Msezane, a former seasonal agricultural worker from South Africa, wrote in an email when she first reached out to me more than a year ago.

This message set in motion the largest journalistic investigation ever undertaken into the UK’s seasonal worker visa, which months later culminated in nearly 50 worker interviews and with Sybil giving evidence before a House of Lords committee. During the course of our research, I felt a similar shock to Sybil’s, as I discovered just how common her experience was.

Since before its launch in 2019, human rights organisations have warned that the way the visa was designed was a perfect recipe for exploitation. The visa limits workers to a maximum six-month placement in the UK horticulture sector. They are also tied to their recruiters, who have the power to decide if and where they can get jobs. Furthermore, workers have to pay for their own flights and visas, meaning many arrive in the UK with huge debts they need to pay off.

Finding and speaking to these workers is not always easy. They live on the farms where they work and many are worried that they will face repercussions if they speak out. But one of the benefits of working at a nonprofit newsroom like The Bureau of Investigative Journalism is time, a luxury

This approach bore fruit. The people who spoke to us reported a litany of problems, from not going to the toilet for fear of not hitting targets, to workers fainting on fields as they picked fruit during heatwaves. Some said they would be shouted at or punished for not hitting these targets, for having their mobile in their pocket or for talking to work colleagues while on the field. Others said they were threatened by recruiters with being deported or blacklisted.

Many were left in debt and destitution, and some left the UK being owed money by their employers.

Workers also reported that the accommodation they rented from farms was often in poor condition, with one worker later telling the House of Lords that his caravan was so cold that some nights when he went to sleep, he wasn't sure if he would wake up in the morning.

There are so many allegations that there is not enough space to list them all, but it does not have to be this way. Following our investigation, a coalition of 19 NGOs and academics wrote to the government asking for a number of reforms to the scheme, including ensuring that workers do not end up in debt as a result of working in the UK.

To date, most of these recommendations have not been taken on board. Instead, the government continues to expand the scheme, while workers wait for a viable route to justice.

OPINION ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 9 ISSUE 11

This piece is part of Exploits, a series from Wicked Leeks and Live Frankly, to highlight the systemic poor conditions faced by people working in food, farming and fashion.

Above: Low milk prices are forcing dairy farmers to intensify.

Below: Seasonal workers are often exploited.

Credit Anita Jankovic

Green dragon

Pictured: Deborah Meaden is an influential voice.

Pictured: Deborah Meaden is an influential voice.

Entrepreneur Deborah Meaden on getting businesses to act on climate and where her confidence came from.

Words by Nina Pullman

Ilove business and I care about the environment,” says Deborah Meaden of her twin passions, in a typically straightforward, straight-talking way. We’re speaking over Zoom and Meaden is at home with her dogs after returning from a morning horse ride, admitting she's “a much nicer person when I’ve been riding."

Meaden is something of a rarity in business in a few ways; a woman with a high profile, a vocal critic of Brexit and outspoken on the need for climate action.

The 64-year-old made her money by buying and expanding the family holiday business, before rising to fame on BBC1’s Dragon’s Den, investing in start-ups and teased by her fellow dragons for her interests in environmental issues.

But it was a prescient interest, as it turns out, as she is now arguably one of the leading spokespeople for ‘green’ business. Nowadays, she also presents a BBC 5 Live radio show and podcast, The Big Green Money Show, and is known as a leading commentator and consultant

THE BIG INTERVIEW / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 11

dragon

on ESG (that’s environmental and social governance in business-speak), alongside her ambassador roles for prominent wildlife charities the RSPB and Tusk.

Her latest project, a children’s book called Why Money Matters, talks six-to-nine-year olds through basic finance, helping them foster a healthy relationship with money. After a publisher approached her to write the book, she briefly wondered whether she’d know enough about how childrens’ minds work, not having them herself. “But how hard can it be?” she recalls thinking, before laughing uproariously. “I thought I’ll just write what I think they should know and then I’ll just simplify it. It was such a good exercise. And it made me realise how we over complicate things as we get older.”

Meaden laughs frequently and loudly, but never in a self-deprecating way; she seems genuinely amused and full of energy. Confidence is certainly not a quality that she lacks, as you might imagine from a person in her position. Though it’s a confidence that feels empowering, rather than arrogant, and the sort you feel could turn a lot of women’s worlds around.

“I’ve never suffered from a lack of confidence and that is actually quite a powerful thing,” she reflects. “It’s quite a gift. I don’t know why that is. Maybe, I had a mother who had a really tough start and I saw her work her way out of it.

“But that is my approach to life: whatever happens, I’m going to be able to find a way over it, and that does give you confidence. Knowing that I’m not stupid, I genuinely think to myself, if I’m not understanding then it’s not my problem; you’re obviously not getting the message across.

“It's a simple thing to fix but a hard thing to fix. It’s simple because you start putting the onus on the other person – and that is an issue because women do tend to take responsibility,

[they say] ‘it’s my fault, I know it’s my fault’.

“And I don’t think that. There are definitely things that are my fault, but to be able to recognise the moment when you think ‘hold on a minute, this isn’t me, this is you’, and being able to say that is very powerful.”

It’s no surprise that, with her interest in clarity, Meaden has mastered the art of communication and become a rare link between the closed doors of finance and the rest of the world – a role perhaps jointly inhabited only with Martin Lewis. “I just come across so many people who overcomplicate everything,” she says. “I don’t know if that’s intentional, because that could mean fees if they’re advisors. Or it could be that it makes them feel cleverer. I am always that person who says ‘I am not stupid so you’re just going to have to keep explaining.'"

She will, she says, often ask “a really basic question” in a room full of people, using her position of influence to demonstrate that it’s fine to ask questions

FEATURES / THE BIG INTERVIEW 12 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

I’ve never suffered from a lack of confidence and that is actually quite a powerful thing.

Above: Dragon's Den first aired in 2005 on BBC2 with Meaden joining on the third series the following year.

and encourage others to do so. Less flashy than her offers of £100k for 20 per cent of your business, perhaps, but no less of a leg up and a subversive counter to exclusive business environments.

Describing herself as a purist when it comes to fossil fuels (“they’re bad news and we need to get rid of them”), Meaden does not hide the fact she believes we need to act faster on climate action, and has tweeted in support of direct action group Just Stop Oil. In her personal life, she follows a vegan diet and hasn’t flown long-haul for five years, though she will be travelling to Antarctica this winter with her husband Paul. “We’ve made a conscious decision not to fly as much because I can’t be worried about the planet and not be prepared to change my behaviour,” she says.

But for all her environmentalism, she is also an entrepreneur at heart and sees the limits on what businesses can do without becoming redundant.

Her podcast and radio show, which interviews high-profile brands like EasyJet and Nestlé, treads this exact line and more than once raises the question, to my mind, whether changing the practices of multinationals is ever going to be enough to transform global society.

The premise, as she puts it, is that: “There is not a business in the world, including my businesses, that when you turn a stone over you don't think ‘I shouldn’t have done that'. We should be encouraging the good behaviour.

“A couple of times I was criticised for talking to them [EasyJet and Nestlé]. But my view is these are the people who change the world. Actually consumers change the world – consumers say 'we want a different

way' and businesses respond by showing them a different way.

“The problem with climate is that it will get beyond our control. My sense of all of this is that human beings are amazing when we put our mind to something,” she says. “The question isn’t 'can we do this?' The question is 'will we do it, in time?' Yes it’s doable. The fear is that we will drive ourselves to the edge, and climate change is different to everything else.

“I’m very hopeful that businesses are on board – not all businesses, though some are doing some fantastic stuff. I’m fearful that we’re not going to tackle it in time.”

Given this deadline, should we not radically change the way we fundamentally buy and produce things, rather than tinkering round the edges? A difficult question perhaps for someone whose passion is selling goods and services, albeit trying to do so with a lower impact.

“Yes of course, that would be my hope,” she says. “But the honest truth is we wouldn’t like it. We would not accept the scale of change at the speed at which it needs to change. And maybe that’s why I got such big names, because as a businessperson I can get the problem. Because actually the answer for EasyJet is to stop flying. Would we like that?

“Honestly, would everyone like not being able to go on their holidays and not being able to go to Spain or Greece? We’re fearful of change. We like gradual change. I have sympathy for some of these businesses –they are at-the-end-of-the-day businesses.”

On the other hand, reflecting on whether she has ever been ostracised by the business community for her outspoken views (as well as climate change, she is vocal on the negative impact of Brexit for business), she says: “What I do get sometimes on a one-to-one basis, is ‘our van was stuck on the M3 for three hours because of [Just] Stop Oil’. And I’m quite quick to point out that if you think that’s inconvenient, you wait to see what climate change delivers on our doorstep.”

She’s also sharp on how to spot greenwash. “Anyone claiming to be completely sustainable, it’s rubbish. Everything we do has an impact.

“You should be able to, very quickly, understand what a company’s version of green is. If you go onto a website and it

THE BIG INTERVIEW / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 13

Above: Meaden has invested in over 60 businesses during the series.

Credit BBC Graeme Hunter/Caroline McDonald

Credit BBC Pictures

Credit BBC Pictures

takes 27 pages to find in some dark corner embedded in their website what their policy is, then I wouldn’t trust it,” she says, adding that a good business should have “a tab right there saying ‘this is what we mean by green’”.

“What I say to my businesses is: ‘say what you mean’. What do you mean by ethical? What do you mean by green? Actually what builds trust is telling people what you’re not doing, as much as what you are doing.”

It’s fair to say that not all the world’s problems lie at the feet of big business. In the UK, at least, the issue of affordability and widening inequality is just as much of a barrier to meeting the challenge of climate change. The cost of buying sustainable products, whether that’s organic food or taking a train instead of a plane, is so much more that it immediately alienates large proportions of the country. There is only so much even an ethical business can do to solve this when faced with the macro trends

of economic instability, rising house prices and stark societal inequality.

“Anybody in this country not being able to afford food, we should all shudder,” agrees Meaden. “We really should shudder at that. I agree with breakfast clubs for children. And I do think there has got to be a Living Wage. We can’t live in a society that is getting a wider and wider gap between the uber rich and those who can’t afford to heat or eat. I mean that’s wrong. That’s not right, is it?

“We know what the answer is but we don’t like it when the answer affects us. When you’ve actually got to pay more tax into the system, then everybody doesn’t like it. But who pays for it? I’m one of those people; I don’t mind paying tax. I do mind how my money’s spent.

“My book has a big section on tax, even for six-to-nine-year olds. If you want a happy, healthy and safe society, which surely we all do, if we want that, we have to pay into that. This is exactly what my book’s about: a healthy mindset with money.”

We can but hope that some of Meaden’s millionaire peers may also have a read of what is already a best-seller on young children's book lists, but in the meantime she also thinks the government has a role to play. Though, rather than being drawn on rental caps or Universal Basic Income, as a true businessperson she believes that fixing the economy has to be the first step, along with support for the supply chain and farmers to prevent prices rising while they invest in more sustainable practices.

“If you can pay for it, pay for it," she says. "Because that helps generate a market and once you get a market, prices come down. If you can’t pay for it, I do think there needs to be some governmental support. Because it will always be the most vulnerable who are hit first.

"I do think the government must play a part in making sure that the most vulnerable are protected in the intermediate stages as we transition to clean energy and net zero. Once we get on our path, what’s not good about cheaper energy, better food security,

FEATURES / THE BIG INTERVIEW 14 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

Anyone claiming to be completely sustainable, it's rubbish. Everything we do has an impact.

Left: Meaden is an animal lover and owns several rescued racehorses.

Credit BBC Northern Ireland

cleaner air? But it’s the transition bit in the middle that is the problem."

She has much sympathy for farmers "doing what they were asked to do, which is after the war, feed the nation". "We now realise that is unsustainable and we need to switch to a different food system. There needs to be support for farmers to switch. Because it is going to be lower yield and then they will get criticised for it being more expensive. In that interim period we’re all going to fall out with farming, completely unfairly. Because they’re doing what we’re asking them to do.

“So there needs to be support for farmers, whether that’s tax breaks or subsidies to encourage more biodiverse farming.”

For many involved in the cultural and political aspects of a green transition, the answer, in part at least, comes down to what the government will do to enforce new ways of helping us live greener lives and running greener businesses.

Though her work is mostly involved in the dialogue between consumers and business (she is a keynote speaker at the Blue Earth Summit this October), Meaden has “conversational” contact with government ministers on an informal basis, several of

whom she has met with in person. “I’m very happy to step in. I will not align myself with any particular party until I know what their policies are and until I believe they will follow them through," she says.

“I’m not suited to politics because I won’t toe the line. I won’t say what I won’t believe in and I wouldn’t tell my constituents what they wanted to hear. And I would last two seconds flat. I consider my position as a good, loud commentator. That’s how I think I should use my voice best. And sometimes to commentate from the outside is as powerful, if not more powerful, than being inside the system.”

Meaden is not known for the glamorous lifestyle of multimillionaires, such as those of some of her fellow Dragons, instead spending most of her spare money on restoring their old Somerset farmhouse. “And I like investing. It’s what I do,” she adds, describing her work as “energising”. “I love finding businesses that just need

that little bit of help. I love it because I love people. The people I talk to are so creative and so full of energy and ideas, how can I not love that?”

But while money doesn’t make you happy (she “knows a lot of very unhappy multimillionaires”), one thing Meaden does know is the power of money to get you somewhere. And with some of her boundless energy focused on the environment, she clearly believes in the power of finance and her own position to bring the two together. As she puts it: “I’ve seen a big change in business, which is fantastic because actually when it becomes a commercial thing, that’s when you get people who aren’t terribly interested in climate change or net zero or biodiversity, but they’re driven commercially, and that means you can sweep everybody into it.

"And that’s what we need, for goodness’ sake. We can’t sort this out in silos; everybody needs to be on board.”

For

THE BIG INTERVIEW / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 15

There’s lots on this autumn at our Devon farm restaurant. Enjoy Marianna Leivaditaki’s Mediterranean Feast, flavours of Cornwall at Emily Scott’s Time & Tide Supper, and irresistible vegetarian creations by Ravinder Bhogal. SPECIAL

Emily Scott

GUEST CHEFS

more info, scan the QR code or visit theriverfordfieldkitchen.co.uk 01803 227391

Ravinder Bhogal

Marianna Leivaditaki

Climate change is different to everything else.

FAIR

ENOUGH

What does fairness mean to different people working and eating along the food supply chain? We spoke to a farmer, picker, retailer and eater to find out more.

Interviews edited by Nina Pullman

THE FARMER

The reason I set my business up was because of the unfairness in the supply chain. I sometimes liken it to a drugs gang regime, where you’ve got the big boss at the top and the little minions in the middle doing the dirty work. And they do exploit that power in the middle.

Farmers are very transparent and have to show their audits for Red Tractor or RSPCA, and there should be that level of transparency further up the chain. The processor and supermarket know exactly what it costs to produce a pig; we don’t have a clue what cuts the processor is selling and no idea at all about pricing. All the time, the government says it’s been talking to the supply chain; what they

mean is they’ve been talking to the CEO of Tesco, they’ve not been talking to the farmer. Very rarely do they actually speak to a farmer. Contracts need to be no less than 10 months. Some people are only given three months’ notice. One of my colleagues lost her contract purely for being too gobby – that’s just commercial retaliation.

For me, 15 years’ ago we were supplying a large processor and the product was going into Tesco. We were asked to go fully free range with a promise of a premium. Then a couple of weeks into the contract, after making all the investment into infrastructure, they decided there wasn’t a market for it and they weren’t going to pay us a premium. So I thought ‘bollocks to this, let’s go direct’, and that

was when we established a brand. We have amazing relationships with all of our customers. That’s now one of the most enjoyable things that we do. They’re friends, rather than this big organisation that’s going to beat me with a whip. When I had a backlog, they all helped me out when I was at my wit’s end, and that’s what a working relationship should be like.

What would help others have these conditions? A whistleblowing line would be good, to call out bad behaviour. The supply chain reviews are a good chance, but it’s actually really upsetting in this day and age that you have to put in legislation for people to act with just a bit of human decency. Payment terms are hideous; I think it takes 90 days for processors to pay farmers. Why does it take 90 days for the money to get back when we’ve already invested 10 or 15 months in advance? The retail price on the shelf is absolutely no reflection of what gets back to the farmer. Having seen Dad go through the peaks and troughs over the last 30 years, it was just enough; I want to be in control of my own destiny. It was definitely the right decision.

FEATURES / XXX 16 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

SUPPLY CHAINS

Anna Longthorp, pig farmer, owner of Anna’s Happy Trotters and former supermarket supplier.

Illustrations by Nathalie Lees

THE PICKER

Most workers we know paid fees in coming to work on farms in the UK. It all starts at the point of recruitment. If you want to break the chain, you have to get to the roots. You can talk about farms, conditions. This is all important. But this research, if it is to be effective, has to consider the roots, and this begins with fees.

The main problem is that ‘agents’ – brokers, middlemen – sell fairy tales to people about the UK, giving people a false dream. We must send information to new applicants, from Nepal, from anywhere, to not believe these scammers. Only you yourself can apply to the Seasonal Worker Visa. If they say they have representatives in official companies, don’t believe them!

I have faced this problem. Later on, after applying, I came to know this: that I was a victim of fraud. I trusted that broker who sold me a lie. They say this everywhere, not just in Nepal. In India, too, and Indonesia. Everywhere. Every broker says the same thing: they have their representative at the licensed recruitment company.

We need a solution to this, to make the process reliable and easy, so no one has to go through these brokers. It’s so deep, this scam. It’s deeper than the sea. I know how it works. So, there must be a better system, an authorised application system that can be properly controlled, with proper information. Otherwise, this will continue to happen. Not just in Nepal, but everywhere. What should be done to solve these problems? The UK government, if they want to hire people for the Seasonal Worker Visa, could give the opportunity

via one authorised department of the country they are recruiting from. They must give a trusted authority, an official organisation, the ability to sponsor workers. If licensed recruitment agencies had connections with the Nepalese Department of Labour, they could hire people through that department, with clear information provided. This official public organisation, they could check to make sure people have not been scammed along the way: a regulated and safe way to recruit. They should also establish an information centre to go alongside this, to spread the correct and accurate information; to make it clear that people can only apply through the official department. They should advertise how many places there are, and make it a fair process. This would also help the UK, to stabilise the worker shortages, to create a fair system and put food back on the shelves. If they want to help their own farming sector, they must listen and take our advice. Otherwise, these fees and scams will simply continue everywhere they go to recruit. If the system is fair and clear, workers will come to the UK with a fresh mind, a positive attitude, contribute to the economy and solve the problems of food and labour shortages. And they will return as well; reliable for all parties. We have to look after labour. The recruitment agencies need to look after labour, and not ignore us, like they did.

Anonymous Nepali seasonal worker recruited to work on UK farms. Collated for the report by Landworkers’ Alliance, ‘Debt, Migration and Exploitation’.

XXX / FEATURES

SUPPLY CHAINS /

If the system is fair and clear, workers will come to the UK with a fresh mind.

THE RETAILER

Our strapline is ‘Fair for all’ and in very simplistic terms that is our ethical stance. It’s about relationships, gratitude and respect throughout that chain.

What we’re working towards is people first; people and planet. They go hand in hand. It certainly starts with the expectation in our contracts of how we conduct ourselves with one another, even down to email language. So in a very open-hearted way,just reminding people about having a generosity of spirit towards each other. That is where it starts, because once you foster that in your team, that helps people understand how they deal with a supplier or a customer. And as the founder and MD, that starts with myself: how I come into work in the morning and what face I choose to put on. All that kind of stuff makes a difference, and sets a tone for others and how we do meetings. One thing we do is go round the room to say something we’re grateful for, because it’s all part of a culture, and culture is one of the most difficult things to shift in business.

With suppliers, it’s fairly straightforward. It’s so hard in the primary production area of food, and they’re so badly treated in some ways. We work really hard to make sure they’re long-term relationships, and when things go wrong we sit down in a respectful manner, and we’re not shouty about it. It’s [about] trying to be forgiving and understanding, and we’re all in this together. With customers in store, it’s about welcoming people with respect. Sometimes we build great new bonds with customers and they become regulars and their average spend goes up. Other times, they’re eyes down and just doing what they need to do. The diversity is huge, but our job is to be welcoming and open hearted. But I

won’t hide the fact that we are in a really tough market. The experience of Covid followed by the cost-ofliving crisis has raised people’s sense of fear and caution.

While we have a great model, we’re having to work really hard to be sustainable. It means trying to compete with the supermarket model of giving people lots of offers and reasons to come back, and being highly competitive wherever we can.

Whether we like it or not, the organic market has come down quite a bit; the demand is nothing like it was even a couple of years ago. Going into the mainstream grocery market, it is quite hard to see how you can get them to wake up, because it is about changing the whole paradigm of profit and shareholder, which is their biggest driving force. But if that’s asking too much, then [they could] genuinely bring in the local. You’ll go to a French supermarket carpark and you’ll see half a dozen stallholders turn up every week. It’s more than allowed, it’s encouraged. You would never see that in our UK supermarket carparks, and yet the customers would love it. Do it with the Cheddar strawberry grower –get them to come in, and they take all the money for that day. It just gives people something to hope for, in a funny kind of way.

Phil Haughton, founder of the Better Food chain of shops in Bristol.

FEATURES / COMMUNITY 18 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12 XXX

SUPPLY CHAINS

Culture is one of the most difficult things to shift in a business.

THE EATER

I feel food choice is very complicated. We all believe that it is a simple matter of walking into a supermarket or a store, picking what we need or what we want and then going home. But I don't feel like our choices are necessarily our own.

I believe that our choices are influenced by our environment and by the places that we go to. So for example, if you are a low income earner, there are a lot of constraints in what you can buy, what you can afford and how you feed your family.

Low-income earners will be more likely to

pick cheaper foods to get value for money, whereas those that are a little bit more affluent are able to go to places that offer healthier choices.

I see that it all starts with the understanding that we are part of the system and that our individual choices feed into the system. As consumers, we generally seek convenience and low prices, which in themselves aren’t bad, but ends up putting pressure on the producers. I’m drawn to the idea of putting pressure on businesses, interest groups and the government to make significant change. I’d like to see businesses changing their methodology and government holding them accountable through various measures.

I have seen glimpses of fairer food supply chains when I was previously a member of an organic food cooperative. Local farmers got together to supply fresh fruit, vegetables and meat locally. The food was available for supply at a farm shop they set up and available for local delivery. Excess produce was available at a secondary location within the local town, with that set up as a food bank but styled

as a farm shop to reduce the stigma of using a food bank. This cooperative also worked with local butchers and bakers. What impressed me about this system was how food was distributed in a manner that benefited everyone. Whether you were the farmer, consumer, retailer, distributor or a general member of the local community, the cooperative worked to both benefit and incentivise everyone. It is generally taught that businesses exist to make money. The common misconception is that the majority of them make money at the detriment of providing positive value to society.

I believe that businesses in the food system need to adopt the concept of being collaborative and working to benefit everyone in the system. By working in a similar way to the cooperative above and committing to be part of a local community in some form, there could be a lot more positivity in the food system, which would allow businesses to make profits while supporting each other, supporting the economy and supporting communities.

Sam, a food citizen and member of the public. As collected for the national conversation on food (#TheFoodConversation).

COMMUNITY / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 19 XXX /

I see that it all starts with the understanding that we are part of the system.

SUPPLY CHAINS /

Riverford's Fair to Farmers Charter

Farmers live with constant uncertainty; never knowing what they will be paid or when, how much of a crop will be bought, or whether it will be rejected altogether.

If all retailers committed to these principles, the lives of farmers would be transformed – giving them stability, a reliable income, and protecting the future of British food and farming for the long term.

That's why organic veg box company Riverford is launching a campaign to call for others to adopt its Fair to Farmers Charter, a living document and agreed list of terms of how it buys from and treats all of its farmers and producers. With shortages on shelves and farmers going out of business, the time is now to create a food system that works for all. More information coming soon on riverford.co.uk.

FEATURES / SUPPLY CHAINS 20 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12 Subscribe now Get the stories that matter, straight to your inbox. Sign up to the Wicked Leeks email for exclusive news, opinion, features and lifestyle on sustainable food and ethical business. Scan the QR code or visit wickedleeks.com/#join Buy what you committed to buy Pay what you agreed to pay Pay on time Commit for the long term

on fair specifications

Agree

fairer wayrewild? to

As the pressure of food security sharpens, where does that leave rewilding and returning land to nature? Jack Thompson reports.

REWILDING /

Pictured: A brown hare in the fields at rewilding estate

Wild Ken Hill in Norfolk.

Since the dawn of time, this is the first time as a society that we're looking at massive-scale nature restoration,” says Sussex farmer James Baird, whose initiative Weald to Waves is setting out to connect 100 miles in a first-of-its-kind nature corridor.

“So we will be forgiven for getting it wrong and if we then set the [food] security balance out,” says Baird, alluding to how the Ukraine war has sharpened the debate over how much food we produce on British soil, compared to how much land is given over to nature.

Where does this leave rewilding and nature-reviving projects in the tug-of-war between food production, climate change and biodiversity loss?

Baird began to grapple with this question after a trip to Borneo in 2016 where he witnessed the “wild west” of palm oil monoculture and deforestation.

“It had a profound effect on me,” he says, recalling how when he asked explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison what he could do to help, he was told to “look at your own farming systems”.

From here, he saw the same, if not more subtle, patterns of destruction at home,

where centuries of farming, building and industry have made England one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

“It was an awakening,” admits Baird. “When I came along in 1971, my father had already cleared the landscape.”

He raises a poignant question: why should the UK expect others to protect rainforests when we’re not willing to do the same?

To answer it, he has partnered up with Charlie Burrell, owner of the renowned Knepp rewilding estate, to dream up the Weald to Waves wildlife corridor and join

farms, estates, gardens and schools in miles of continuous wildlife habitat.

But it’s not rewilding, as Baird is keen to point out. Rather, it’s a collaborative approach to large-scale nature restoration.

Based on pledges from anyone in the area, there are over 20,000 hectares of potential sites. Already, there are more than 50 community gardens, orchards, climate groups, allotments and gardeners who have pledged to protect 15 targeted species, including hedgehogs and slow worms, by adapting gardening practices and creating habitats. Burrell talks of how the project could “reconnect landscapes that have been fragmented from each other”, allowing wildlife to pass over roads and train tracks. This will require farmers, councils and community groups to collaborate, but he is keen the project doesn’t sound “dictatorial”. “I think if you start off by saying the best thing you could do with this landscape is X, Y and Z, it becomes them saying, ‘but I'm not going to do that’. We all know what we can do and the limits to our land,” he says.

“This isn't a project,” adds Libby Drew, director of the Knepp Wildland Foundation which oversees Weald to Waves. “This is an

22 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

Why should we expect others to protect forests when we're not doing the same?

Clockwise from top: Corn marigolds at Wild Ken Hill; a group of community rewilders; freshwater marsh is a valuable wild habitat for nature.

Credit Heal Rewilding

Credit Graeme Lyons

environment for which you could do more efficient, more collective work.”

As such, Baird sees different opportunities for nature on his farm next to the sea near Newhaven; from reviving coastal grasses to not silaging when lapwings are nesting and simply throwing away the hedge trimmers. While much remains to be decided, the initiative has concrete plans to restore the rivers Arun and Adur that give the corridor its shape, working with farmers, landowners and partners to reduce the flood risk and pollution.

Perhaps most significantly, the project is an example of how we can make large-scale changes for nature, such as flood plains that could cross multiple areas of land.

This new, more collective approach to nature restoration is gaining interest in farming communities where rewilding can be met with animosity.

But not everyone feels there is enough time to bring diverse groups together with the urgency facing the natural world.

Founding member of rewilding charity, Heal, Jan Stammer, felt the situation was too urgent to wait for markets and farmer consensus. Instead, her organisation is buying land to rewild by crowdfunding, selling three square metres of land to

individuals and businesses concerned about the state of nature.

The project came from the former PR director’s desire to “help make a difference, no matter if you had a pound or a million pounds,” shifting rewilding from a luxury afforded to estate owners and private corporations into the public realm.

In late 2022, Heal bought 460 acres in Somerset and has started the process of rewilding, starting by measuring baseline biodiversity levels before deciding which course of action to take, from introducing large herbivores to restoring wetlands.

The group already has funding for another site in the north of England, gaining ground on its ambition to acquire 49 Heal sites and “a thriving reservoir of nature in every county, accessible to everyone”.

But what is the trade-off with food production? Will leaving more space for nature lead to the UK importing more food from abroad, driving nature loss elsewhere?

Stammer is not deaf to these concerns but lists more practical limitations. “We couldn't afford better quality land,” says Stammer, explaining that Heal’s land is of moderate to poor quality, or in technical speak, grades 3b and 4. “We would always be looking for land which is more difficult to

farm because that makes sense in terms of what we recover for nature.”

Add the demand for new houses, renewable energy and biofuels, and the competition for land is only getting tougher. Dominic Buscall, a farmer and rewilder in Norfolk, says farmers need direction from the government to tell them what society needs from land.

The government’s land-use framework promises to negotiate these competing demands alongside legally binding commitments such as net zero. This could, in theory, demonstrate how action on one area, such as climate change, could reinforce or undermine progress in another, like biodiversity. It is due to be released this year, but as a complex policy, it faces a slow journey through parliament.

Whether you prioritise food or nature, one thing is certain: the system doesn’t currently work for either. Buscall believes we need progressive change across the entire food system: sustainable farming, healthy food production, supermarket regulation and coherent policy. As he puts it: “The status quo will not deliver food security.”

But the tide is turning, according to Stammer, who is seeing nature protection adopted at every scale; whether that’s councils leaving verges un-mowed, or rewilding anything from one acre to two thousand. Perhaps what you call it, whether rewilding, nature recovery or otherwise, matters less and less. As Stammer says: “We don’t put time into arguing. We just get on with it.”

REWILDING / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 23 Refer your friends Get £15 each for you and your friend when they join Riverford Scan the QR code or visit riverford.co.uk/refer

Competition for land is only getting tougher.

Celebrating

COMMUNITY

To celebrate Wicked Leeks turning five years old, we asked our readers for nominations of their own food and farming heroes. Here are some of our favourites.

From the editor... It's been a wild ride since autumn 2018, when I pressed 'publish' on the first ever Wicked Leeks article. Five years on and here we are - thanks to you, our brilliant reader community, who have kept us going with your questions, comments and positivity. NP

I would like to nominate Laura Stratford, coordinator of the Greater Lincolnshire Food Partnership. It’s dramatically grown as an organisation over the last few years in terms of geography and numbers of members and partners, far too many of which are food banks in this unfashionable and disregarded corner of the East Midlands (one of the ten most deprived regions of northern Europe). The need is stratospheric. Laura copes with a burgeoning workload with unending good cheer and dedication, always seeking to improve the region’s food system through practical and creative ways. From helping to fundraise £10k for an exceptional food bank in just one night, to organising workshops for bakers and local wheat farmers to develop a nutritious bread ecosystem in the county. Laura’s commitment is exceptional and the region is lucky to have her.

Foodstar

STAR LETTER AND WINNER OF FOUR RIVERFORD VEG BOXES

I have so many people who I’d like to mention. Firstly, Roger from White Lake Cheese. He’s so passionate about his cheese and a fantastic person. He loves to experiment with new artisan cheeses and is forever getting people into share his kitchen to dream up new ways of using cheeses. Secondly, David from Wraxall Vineyard. David is new to growing and making wine but he’s bought a vineyard and is doing tremendous things to improve the health of the vines and build a brand that attracts people to the area. Thirdly, Paul from Black Bee Honey. The team have worked really hard to get B Corp certification. They produce single origin, British honey and are really championing the industry and beekeepers across the country. I’d also love to champion Hugh from The Frome Food Network who has done a fantastic job creating a network for Frome-based farmers/growers/ producers and many more of us that fall into ‘other’. Through the network I’ve met so many amazing people, been on farm tours, and have really found my tribe. A group of people that want to do better with food for people, planet and pocket.

Vicky Hunter-Frigerio

FEATURES / COMMUNITY 24 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

Given children’s vegetable consumption continues to decline, TastEd’s work is even more vital today than ever. The most under explored part of this problem is figuring out WHY children aren’t eating veg. It’s largely because they don’t like them, have no experience of them (are unfamiliar and scary) or have never tried them. TastEd addresses all this gently with children, free from lectures about health and nutrition. Going through joy, pleasure and fun, alongside peers and trusted adults, means children’s natural curiosity takes over. I’ve seen children sit on their hands when presented cauliflower – but at the end of a TastEd session have not only tried them but go home telling parents they actually liked roasted cauliflower. TastEd is so simple, so cheap and easy to run and so effective, we need to urgently get all schools and early years children doing it.

Kim McGowan

I’d like to celebrate our daughter Kate’s incredible achievement in persevering with her dream and building her vertical indoor farm in Kent. GrowUp is now producing bags of delicious salad leaves without any pesticides. It can’t be called organic as it is not grown in soil and therefore does require fertiliser. We’re so proud of what Kate and her team have accomplished after ten years of solid grind.

Deborah Hoffman

I would like to nominate Jo Cartwright. Jo runs an organic rare breed farm in Swillington near Leeds. She also has one of the very first CSAs – community supported agriculture – in the country, operating in her two-acre walled garden. Jo has a small poultry abattoir where she is licensed to kill and prepare her own meat birds. She welcomes visitors to the farm about once a month when she has meat ready for sale, and hosts school visits. Her ancient woodland hosts a forest school business, run separately from the farm. She is currently farming solo and would love someone competent to help with a farm share. On top of this, she does farmers' markets around the area. An amazing woman.

Barbara

Rhodes

Wild by Nature need celebrating! They are doing amazing things using regenerative farming methods, working with nature. Sammy Smith, head butcher, produces amazing charcuterie in their butchery on the farm in the Black Mountains.

Fen

PriorSmith

I would like to nominate the whole volunteer team at FoodCycle Peterborough who work so hard every Monday to produce a delicious three-course vegetarian nutritious meal for those in need in our community. They use the surplus food from local shops and farms, including Riverford at Sacrewell, for which we are extremely grateful. The food we receive is always a surprise, which can be challenging but there is always a wonderful meal on the table by midday. We also share our recipes and cooking tips to guests who need help in that way.

Annie B

COMMUNITY / FEATURES ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 25

COMMUNITY FEATURES

Season's eatings

As bitter leaves like kale and radicchio come into season, we hear from MasterChef finalist and author of new book, Bitter, Alexina Anatole.

Why should people consider bitter flavours?

A dish that has saltiness, sourness, bitterness and sweetness, all in balance, is sure to excite the tastebuds on our tongues more than something that is one-note.

What are your favourite foods to cook with that bring a bitter flavour?

Bitter leaves – from milder spinach to bitter, vibrant radicchio – are often interchangeable in cooking and are wonderfully versatile. They can be eaten raw, briefly wilted, added to soups, stews and curries, or used as a filling in quiches, breads (e.g. Turkish gozleme) and pies (e.g. Greek spanakopita).

What are the health benefits?

It’s good to be reminded of all the good things that dark leafy greens can offer: vitamin C (for healthy skin, hair and immune system), vitamin A (for vision), vitamin K (for strong bones) and magnesium (critical to the muscular and nervous system). In fact, bitterness in vegetables often correlates with their nutrient density.

For farmers and producers

A restaurant with a strong, direct relationship with farmers and producers is more likely to be supporting small-scale farms and paying a true price for their produce. Lots of menus will carry the disclaimer 'where possible' in relation to being organic or locally sourced; well, it is very possible if you see it as a priority. Try The Bull Inn (Totnes), The Ethicurean (Bristol) and The Veg Box Café (Canterbury).

For the environment

This starts with the raw ingredients. Looking for organic and seasonal produce reduces impact on land and nature. It is telling that many high-end restaurants have traded opulence for kitchen gardens, solar panels and zero-waste principles. You can judge a place as much on the provenance and carbon footprint as the tucker on offer. Try Silo (London), Argoe (Newlyn) or Pillars of Hercules (Fife).

How to EAT OUT FAIRLY

By chef Bob Andrew

For the staff

The catering industry has been built on bad pay, long hours, zero-hour contracts and the use of tips to bulk pay. It could be as simple as judging if the staff seem happy and proud. Check whether tips are shared between the staff – it is law now, but often flouted. B Corp certification has staff wellbeing criteria, while a handful of businesses have made the move to employee ownership. Try The Riverford Field Kitchen (Devon), The Darjeeling Express (London) and Hawksmoor (London).

For the community

Eat in a café or restaurant that you know is independent; it means your money is going back into the local economy. There are also some shining examples of eateries whose entire purpose is to provide opportunities to marginalised groups, while others provide a vital social meeting place. Try Luminary Bakery (London), Men’s Pie Club (Northumberland), Food in Community (Totnes) and Social Bite (Edinburgh).

26 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

2 1

3

4

A cake for a special occasion

by chef Bob Andrew

For a birthday cake to celebrate five years of Wicked Leeks magazine, I investigated the possibility of using leeks in the mix, considering both savoury and sweet options. The former would be a bake rather than a cake, and the latter would just be unconscionable? However, true to form, we have included some veg here; sweet, earthy beetroot adds moisture and a whiff of worthiness. This recipe owes more than a passing nod to carrot cake, so feel free to use those instead. Grated courgette, squash or even parsnip would work too.

Beetroot, orange, pecan and poppyseed cake

Serves 12

Prep 15 mins | Cook 45 mins

Cook's notes

If you’re feeling fancy, you can decorate the top with candied oranges. Halve two oranges and cut each half into 5mm thick slices. Heat a cup of water with half a cup of caster sugar in a large frying pan. Add the orange slices and simmer for about 20 minutes, turning the slices every so often, by which time the liquid should be a sticky syrup. Remove the slices and cool on baking parchment. You can add a thin slice of beetroot to the pan at the start if you’d like the orange to have a pinkish-red hue, or alternatively use blood oranges if they are season.

For the mix:

200ml sunflower/ vegetable oil

250g light muscovado sugar

4 eggs, divided into yolks and whites

180g beetroot, grated

125g pecans, roughly chopped

2 tsp poppy seeds

½ tsp ground mixed spice

1 tsp baking powder

½ tsp bicarbonate of soda

pinch of sea salt

1 orange, zested & juiced

250g self raising flour

For the frosting:

50g soft butter

125g cream cheese

125g mascarpone

125g unrefined icing sugar

zest of 1 orange

Method

Preheat oven to 180 degrees/Gas 4. Grease and line 2 x 20cm cake tins with baking parchment. Place the oil and sugar into a large mixing bowl or food mixer and whisk together. When they look creamed and well mixed, whisk in the egg yolks, a little at a time. Stir in the beetroot, pecans, poppy seeds, mixed spice, baking powder, bicarbonate of soda, a pinch of salt, orange zest and half the juice. Keep to one side. In a separate clean bowl, whisk the egg whites until light, fluffy and just forming stiff peaks. Sift the flour into the bowl of wet ingredients. Fold it in with a large spoon until no dry patches appear, taking care not to over mix. Next, fold one spoonful of egg white into the cake mix to loosen the mixture,

followed by the rest, folding until the mix is well combined. Do not beat the mixture, as you don't want to knock the air out of the egg whites. Split the mix evenly between the tins and bake for 35-40 mins or until a knife tip or skewer comes out just clean. When ready, cool in their tins for 15 mins and then transfer to a cake rack until completely cooled.

To make the frosting, put all ingredients in a bowl, making sure to sift the icing sugar, and beat until smooth. Keep chilled until needed.

To build, sandwich the layers with one third of the frosting and top with the rest. Garnish as you see fit (see cook’s notes).

Cut a slice and toast the future of sustainable food and the community that’s making it possible (that’s you!).

RECIPE /

For as long as we have been together, Yeshi and I have dreamed about putting Tibet on the food map.

We met in 2009 in Dharamsala, northern India. Yeshi was a Tibetan studying in the famous hill town, and I was a tourist tagging a week’s break onto the end of a work trip to India. We first bumped into each other on a mountain path when we were both taking pictures of the snow monkeys, and later that evening Yeshi invited me back for a meal in the small concrete room he shared with a friend. And that is where our food journey began. The first dish that Yeshi ever made for me was thenthuk, or hand-pulled noodle soup. This smooth, hearty broth banished the November cold from my bones, and its unique flavours had me sold.

Fast forward several years, and Yeshi and I are now married with two young children, and living in Oxford, in the UK. Together we run Taste Tibet, a restaurant, shop and festival food stall which feeds tens of thousands of people every year. I am not the cook! Yeshi brings most of the food to our family table, and he is Taste Tibet’s head chef and chief recipe developer.

WHAT IS TIBETAN FOOD?

Outside Tibet, the idea of Tibetan food as a cuisine in its own right is clearly still evolving. At the restaurant, we are always amazed by the number of people who talk about our food being Nepalese, even though they’ve been enjoying it under the banner of Taste Tibet for years.

At first glance, Tibetan food looks a lot like Chinese food. Noodles, dumplings and small plates are a big feature of the cuisine. In fact, the most iconic flavours in Tibetan cuisine have more in common with the food of Bhutan and Nepal, as well as parts of northern India including Sikkim, Ladakh and Lahaul. The Tibetan kitchen uses liberal amounts of Sichuan peppercorns (known as yerma in Tibet), turmeric and cumin, and plenty of aromatics such as ginger, garlic and coriander (cilantro). A distinguishing feature of the Tibetan diet is that much of it is based on barley or wheat –crops which, unlike rice, grow well at high altitude – with bread often being

the accompaniment to a main meal. There is also a fair amount of dairy, a food type largely missing from the traditional Chinese diet. Hearty soups, stews and broths are another mainstay – in such a harsh environment, hands and bellies naturally crave a constant supply of warming foods with a high energy content.

LIFESTYLE / TRAVEL AND CULTURE 28 WICKED LEEKS | ISSUE 12

Above: Julie Kleeman and Yeshi Jampa with their family; Tibet shares the Everest range of the Himalayas with Nepal.

Food has always offered a way to travel through cultures. Here Julie Kleeman and Yeshi Jampa share the food from the dramatic mountain landscapes of Tibet.

Credit Keiko Wong

The

Credit Keiko Wong

Potato and chickpea breakfast bomb

Serves 4-6

This is such a comforting dish, and it makes the best of all hangover cures. The contrast between textures results in a taste explosion – a bomb, you might say. If you want the dish to have a more curry-like consistency, add a little boiling water during the latter stages of cooking.

Ingredients

2 white potatoes, about 350g washed but not peeled, diced

2 tablespoons cooking oil

½ teaspoon cumin seeds

1–2 fresh green chillies, thinly sliced, seeds removed

1 teaspoon salt

½ red onion, finely chopped

1 large garlic clove, finely chopped

3 tomatoes, diced

400g cooked chickpeas –tinned or cooked from dried

¼ teaspoon turmeric chopped coriander (cilantro) to garnish – optional

Method

Put the potatoes into a saucepan of cold water, bring to the boil and cook until tender. Meanwhile, heat the oil in a wok or frying pan over a medium heat. When it’s hot, add the cumin and toss for about 30 seconds, then add the chillies and salt, quickly followed by the onion and garlic. Stir well, then turn the heat up to high and cook until the garlic and onions are visibly softened and golden brown. Now add the tomatoes and stir well. Bring to the boil, then turn the heat down to low-medium and allow to reduce for several minutes, until you have a thick sauce. Using a slotted spoon, fish the cooked potatoes out of the water and add them to the wok, pushing them down quite hard into the tomatoes, almost mashing them. You’re aiming for a consistency that will work well as a dip. If you are using chickpeas from a tin, drain and rinse them. Add the chickpeas to the wok, along with the turmeric. Stir everything together, then serve –garnished with coriander, if you like.

Travel and food: our top picks

Delight in the decadence of vegetarian cooking in the new book from writer Ravinder Bhogal, Comfort and Joy, bringing joyful influences from her Punjabi heritage and childhood memories from Kenya.

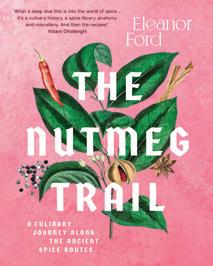

Follow the ancient spice trade routes with author Eleanor Ford in her book The Nutmeg Trail , which combines historical research with a travel writer's eye and a cook's nose into 80 spice-infused recipes.

TRAVEL AND CULTURE / LIFESTYLE ISSUE 12 | WICKED LEEKS 29

Taste Tibet: Family recipes from the Himalayas by Julie Kleeman with Yeshi Jampa (Murdoch Books, £25) is out now.

Credit

Ola

RECIPE

O. Smit

have for dinner? your food

Does it really matter what our food ‘eats’? Modern science and food systems have done a good job of saying it doesn’t, reassuring us that eating food produced using artificial pesticides and fertiliser makes little difference to our health. But new discoveries are untangling the complex web of life between the soil, animals and our bodies, and starting to tell a different story.

In her new book, What Your Food Ate, scientist and author Anne Bicklé says the health of the soil is inextricably linked to our own.

At the regenerative farming conference Groundswell this year, she showed a packed tent how the root structure of the same plant compares when it is fed two different diets; the ‘fertiliser diet’ and the ‘soil health diet’.

While both showed good above-ground growth, in the fertiliser example, roots were sparse and short. In contrast, the soil health example, from farms that use diverse rotations, minimise disturbance (like ploughing) and cover the soil, showed a deep and dense root network.

“Look at the fertiliser diet; excuse my French, but that sucks,” she said, explaining that fertiliser does make the plant grow, but to the detriment of the overall plant and soil health.

Why this matters so much all comes down to the microbes in the soil, or as Bicklé calls it, “the biological bazaar”.

These soil microbes really are remarkable. They help plants fight disease, grow and find minerals. They have, as we are just starting to realise, developed “the grandest symbiotic relationship that we know about on Earth.”

Crucially for human health, soil microbes also mediate the vital nutrients we need for long life: phytochemicals, minerals, micronutrients and fats.

While mainstream nutrition theory says it’s mainly the type of soil and seed that influences the nutritional quality of a plant, Bicklé claims her research demonstrates that

farming practices “profoundly influence” what volume of nutrients we absorb.

It’s certainly a fast-moving field; top nutritional scientist and author of Food for Life, Tim Spector, has previously been in favour of generally eating more plants, regardless of how they were grown. But new evidence, including from Bicklé and her husband and co-author David Montgomery, is building around the negative health implications of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.