An Haute Couture house receives the unusual commission by the British princess to design a wedding dress. During eight months, various people are working on different parts of this secret project without knowing of the final product: the pattern maker in Paris, the lacemaker in Normandy and the hand embroiderer in Mumbai. With her very first work shown in Vienna, French director Caroline Guiela Nguyen tells a story of structural and private violence at hand of the creation of a royal bridal gown. While all those involved are in reality obliged to silence, their fates are being narrated on stage. Guiela Nguyen skilfully presents a touching play about the violence, the pain and the tears (italian lacrimas) that are concealed behind overwhelming beauty.

30 / 31 May, 7.30 pm

Halle E im MuseumsQuartier

English, French, Tamil

German and English surtitles

2 hrs 45 min.

PLEASE NOTE

Recommended for ages 16+

This play addresses mental violence and suicide.

Text, Direction Caroline Guiela Nguyen Translation (English,Tamil,Langue des signes française) Carl Holland, Rajarajeswari Parisot, Nadia Bourgeois With Dan Artus, Dinah Bellity, Natasha Cashman, Charles Vinoth Irudhayaraj, Anaele Jan Kerguistel, Maud Le Grevellec, Liliane Lipau, Nanii, Rajarajeswari Parisot, Vasanth Selvam and on film Nadia Bourgeois, Kathy Packianathan, Charles Schera, Fleur Sulmont With the voices of Louise Marcia Blévins, Myriam Divin, Jessica Herbich Artistic collaboration

Paola Secret Scenography Alice Duchange Costumes and high fashion pieces Benjamin Moreau Light design

Mathilde Chamoux, Jérémie Papin Sound design Antoine Richard with the collaboration of Thibaut Farineau Music Jean-Baptiste Cognet, Teddy Gauliat-Pitois, Antoine Richard Recorded music Quatuor Adastra –string quartet Video Jérémie Scheidler Motion Design Marina Masquelier Hair, Design wigs, Make-up Émilie

Vuez Casting Lola Diane Collaboration video Marina Masquelier, Philippe Suss Dramaturgy interns Louison Ryser, Tristan Schinz as part of the drama school of the Théâtre National de Strasbourg Dramaturgical assistance Hugo Soubise Direction intern Iris Baldoureaux-Fredon Sound design intern Ella Bellone Artistic counselling Juliette Alexandre, Noémie de Lapparent Stage and costumes manufacturing Workshops of the Théâtre National de Strasbourg Translation surtitles Almut Kowalski (German), Rosie Fielding (English)

Surtitles Aurélien Foster

Production Théâtre National de Strasbourg Coproduction Wiener Festwochen | Freie Republik Wien, Festival TransAmériques de Montréal, La Comédie – centre dramatique national de Reims, Points communs – Nouvelle scène nationale Cergy-Pontoise / Val d’Oise, Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Centro Drámatico Nacional (Madrid), Piccolo Teatro di Milano – Teatro d’Europa, Théâtre de Liège, Théâtre National de Bretagne, Festival d‘Avignon, Les Hommes Approximatifs Supported by Odéon – Théâtre de l’Europe (Paris), Théâtre Ouvert – Centre National des Dramaturgies Contemporaines (CNDC), Maison Jacques Copeau, Comédie-Française, Musée des Beaux-arts et de la Dentelle d’Alençon, l’Atelier-Conservatoire National du Point d’Alençon, l’Institut Français de New Delhi et l’Alliance française de Mumbai

executed by the team of Wiener Festwochen | Freie Republik Wien

Premiere May 2024, Wiener Festwochen | Freie Republik Wien

CAROLINE GUIELA NGUYEN IN CONVERSATION

You’re currently in rehearsal for LACRIMA, your first production at the Théâtre National de Strasbourg. Can you tell us a little about your initial intuition and how it evolved over time?

I was thinking of Princess Diana’s wedding dress! I didn’t have an actual memory of it –I wasn’t long born, but my mother had told me about it. Anyway, while researching it, I found out more about everything that was put in place to keep the secret surrounding the making of that dress. And my intuition right from the off was that I wanted to talk about this secret. That’s also when I came across the work of Rieko Koga, an artist who hand-sews words onto fabrics. I was struck by one of her works in which she had sewn the following onto linen: ‘According to an ancient Japanese belief that I still share, sewn stitches have a magical power. The clothes my mother made me when I was a little girl always enfolded me with her great love. And the stitching across the back of those clothes protected me from anxiety and fear.’ And so, as one thing led to another, I gradually reached the stage where I had what could almost be likened to a fairytale: what if all the characters in it were somehow linked to the story of how a dress is made? I even took it a step further: I thought it might be interesting if we found out how anyone who came into contact with the dress would somehow be affected by a curse.

Today I have the feeling that everything propelled me towards the world of couture and, later, towards haute couture, which really is a very secretive world. I was then able to build my story or, rather, my stories, since I’m always working on a harmonious plurality of stories that will interweave and resonate with one another. The setting was then clear: it would be a dressmaker’s workshop. So it’s the story of a princess

who wants the most beautiful wedding dress, and it takes no less than eight months just to make it.

The setting is always the first anchor point in your writing. In this instance, how did the idea of a workshop evolve in the course of your various discoveries and encounters?

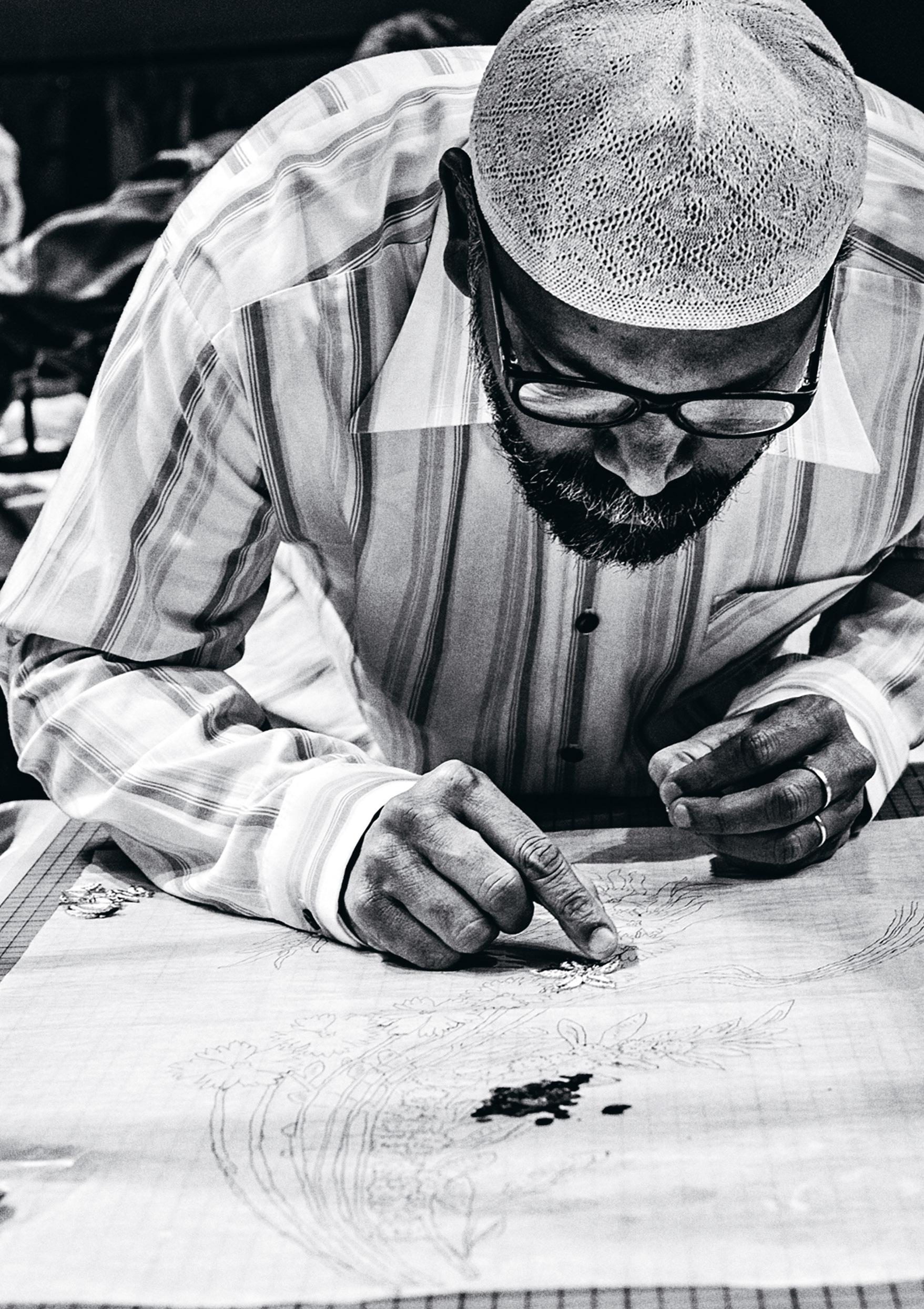

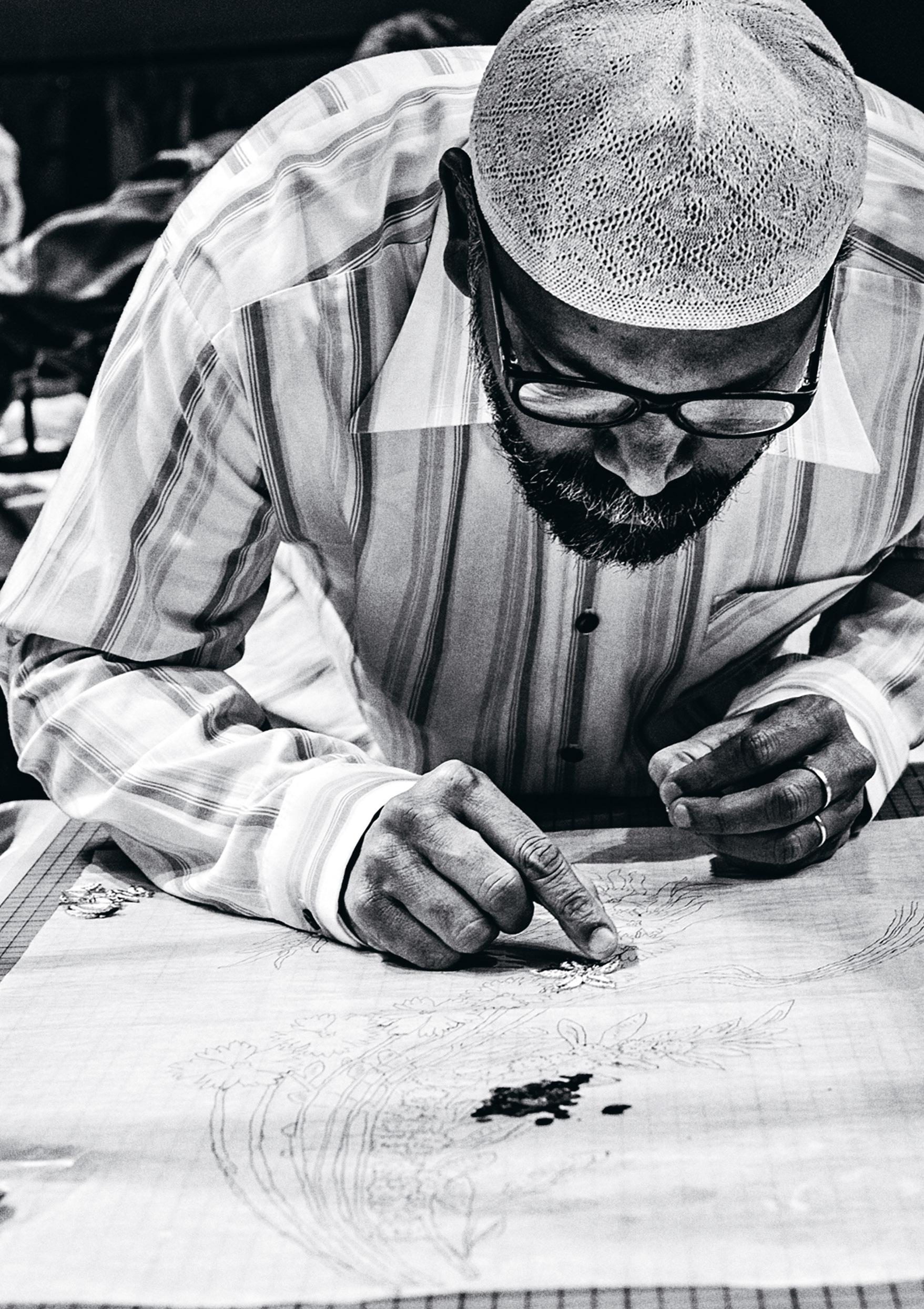

In this world of haute couture, I had imagined an initial workshop, located in the heart of Paris. I spent a lot of time meeting dress designers, pattern makers … the people who work in the various trades that define the world of haute couture. Then the idea of a veil took me in the direction of Alençon lace. So I went to Alençon for a while to meet and talk to the lace-makers and to Johanna Mauboussin, the curator and director of the town’s Museum of Fine Arts and Lace. And again, the issue of secrecy came up. Alençon lace was something of an industrial secret. Next I travelled to India where the embroidery is made. I went to the Mumbai workshops, and it was during that trip that my writing experienced a coup de théâtre; indeed, up until then, I’d wanted to focus everything on the lives of the women. In fact, the embroidery is done by Muslim men; it’s an artisan craft that’s passed down from father to son, and Indian embroiderers are the best in the world. They have expertise that’s second-to-none, and it’s their handiwork you see on the most beautiful garments paraded on the catwalks. So I said to myself: there’s no way I can ignore this subject.

That gave rise to the idea of a transformative setting that would feature three workshops in turn: Paris, where the dress is made; Alençon, for the lace; and Mumbai, for the embroidery. I liked this idea of multiple geographical locations as a

way of talking about a contemporary world that evolves through themes of violence and secrecy.

This secrecy you talk about is even the subject of NDAs, and it’s hard to imagine so many people hard at work never knowing exactly what it is they’re making …

The world of haute couture is a fascinating one: its starting point is a designer’s idea, surrounded by a very high level of complex technical expertise to which we have no access. Mumbai, too, has its culture of secrecy. Before you enter the workshops, you have to leave your smartphone at the entrance and you’re never told which labels the embroiderers are working for. You’re forbidden from asking them questions and of course you can’t take photos … I went there shortly before Fashion Week, and the workshops were going flat out. These events taking place in Milan, Paris and New York have a phenomenal impact on Mumbai. It’s hard to even imagine the embroiderers living thousands of miles away from where the fashion shows are held … LACRIMA is about India’s expertise that benefits Europe and the wealthy countries that profit from it. Of course, the work provides many Indians with a livelihood. So how do you go about establishing a fair and ethical relationship? Can we improve working conditions without creating a post-colonial work relationship, without imposing measures drawn up in a European design department and applied without discussion or exchange with Indian companies and the people who work there? With social media, news spreads very quickly; so there is a fear that something might happen in an Indian workshop that could tarnish their image. So there’s now this race for ‘total transparency’ that runs in parallel with the world of secrecy that has existed for decades.

We’ve mentioned the professional secrecy, but you’ve also woven webs of family secrets as well as more intimate secrets …

I’m not going to spoil the story of Thérèse here, but it’s a recurring theme: the way women have been guardians of the temple of secrecy and/or silence. Even though they themselves have been either victims or witnesses of violence within the family, secrecy and silence were not only embedded in them but even passed on as a legacy. I’m thinking of a documentary that made a huge impact on me: Histoire d’un secret by Mariana Otero. It’s the story of a family where the parents, the father and the mother, had two daughters – in fact, one of them made the documentary. The mother died when the girls were little and, incredibly, no one in their family ever told them about it. There’s a scene where the director goes to see her grandmother several years later and says something along the lines of: ‘Actually, Mama is dead’. And her grandmother replies: ‘Do as I do: sleep’.

You have chosen to work in sessions, i. e. periods of rehearsal interspersed with periods of downtime for the cast. How important is this working method for you as a writer?

I’ve worked this way since SAIGON. I come to each session with written scenes, which I then try out on stage and rework. It allows me to spend time meeting the actors. There are always several languages in my shows, and I want to be able to grasp each performer’s idiosyncrasies: whether it’s the different idioms spoken in French or the English spoken by an Indian, or London English, or Tamil … I want to finetune my writing based on their idioms; that’s important, and it takes time. In LACRIMA, as in my other shows, we have professional and lay actors. So we can’t adopt a

‘classic’ rehearsal routine, i. e. meeting up two months before the premiere and then rehearsing non-stop to bring the show to life. People who have never performed before need a period of adaptation. Even if it’s just about leaving home to go to rehearsals and finding themselves in a theatre all day long. There’s an organic rhythm you need to get used to, and commuting back and forth makes that possible. Also, the work has to be able to mature between the sessions. What’s more, for these lay actors and for me, it’s important that we really get to know one another, and that takes time. The actors range in age from 18 to 82, so they’re really of all ages and from all walks of life. So how do you really get to know someone? You can’t make a plant grow faster by tugging on it.

As an author, letting people into my writing is a journey, and for people who are doing theatre for the first time, you have to build things up over time.

In LACRIMA, some of the actors play several roles. Is this a first in your work?

Yes, I’d never done that before. I obsess about conviction; for me, the fact that an actor could play two characters seemed impossible. At the same time, I did realise that, in terms of fiction, this was restrictive: I couldn’t just bring in a character for a single scene. So I decided to do it for the first time with LACRIMA. I was keen to question this aspect of my work, and I needed that freedom for the writing. Even non-professional actors are capable of playing several roles. It alters the way we see things: before, the audience might have thought that the person on stage personified what they are in real life. Even though that’s never been the case: each person plays a fictional character with a name, a costume and a back story that’s simply not theirs. Even when the person is not a professional actor, it’s really a matter of interpretation. Playing several roles reinforces the relationship with the fictional nature.

Today is February 26 and LACRIMA is to premiere on May 14. Do you know exactly what you’ll be writing or are there still question marks about your plotline?

There are five parts, and I’ve still got the last one to write and I know exactly what the final narrative arc is going to be. As far as the entire package is concerned, it’s now a question of editing and making cuts to tighten up the narrative. I love the editing phase: it’s the second aspect of writing. I have all my story lines, and I know which ones won’t be in the performance. Very early on, I knew how the play was going to begin and end, and that’s a really good sign. There are still two rehearsal sessions left, but in terms of writing, I’m really in the home straight.

You’re planning to film a series based on LACRIMA next. Will you stick to the same characters and the same storylines?

I don’t know yet, but it looks right now as if the series will be a completely new project. I love the idea of having LACRIMA as a stage performance on the one hand and as a series on the other. I’m delighted to have a second space where I can tell the story I want to tell, but in another form, with other characters and other narrative threads. For example, in the stage performance, I’m not going to elaborate on the mystery of the veil. It’s the most monumental piece of work ever created in Alençon, but no one knows who it was intended for. The veil disappeared for years and then reappeared on the art dealer circuit. Who commissioned it? Who wore it, and on what occasion? These are all questions that keep swirling around my brain. It’s a great avenue to explore, and potentially an important thread in the series. Likewise, I’d like to develop the family history of the character played by Nanii. Here it’s just briefly outlined … Certain things that are in a minor key in the show, as it were, could be transposed to a major key in the series. The LACRIMA series will be a spin-off or a ‘sidequel’ to the LACRIMA show.

Caroline Guiela Nguyen is an author, film and theatre director. After studying sociology and training at the École de Théâtre de Strasbourg, she founded the company Les Hommes Approximatifs in 2009. Consisting of professional actors and amateurs, the group develops stories after intensive research with a focus on characters to whom the theatre otherwise pays little attention. Convinced of the power of fiction, Guiela Nguyen seeks inspiration for her texts in places that can capture the problems and difficulties of our time and is in close contact with the people she calls “experts on our realities”. Guiela Nguyen has been showing her plays throughout France since 2013, and in 2017 she presented her play SAIGON at the Festival d’Avignon, which has since then toured worldwide. Four years later, she premiered FRATERNITÉ, Conte fantastique in Avignon, then worked at the Schaubühne in Berlin, among others, and was appointed the director of the Théâtre National de Strasbourg and its theatre school in September 2023. She sees the TNS as a lively and inviting place where the relationship between artistic works and the city’s inhabitants is constantly scrutinised and reflected upon.

PUBLICATION DETAILS Owner, Editor and Publisher Wiener Festwochen GesmbH, Lehárgasse 11/1/6, 1060 Wien P + 43 1 589 22 0, festwochen@festwochen.at | www.festwochen.at General Management Milo Rau, Artemis Vakianis Artistic Direction (responsible for content) Milo Rau (Artistic Director) Text credits The Interview was conducted by Fanny Mentré for the Théâtre National de Strasbourg in February 2024 and shortened for the Wiener Festwochen | Free Republic of Vienna Translation Stephen Grynwasser Produced by Print Alliance HAV Produktions GmbH (Bad Vöslau)

Sponsors

Sponsors

Main

Public

Mobility Sponsors Media Partner