Bullfights are a matter of life and death. The award-winning Spanish performance artist Angélica Liddell puts no less on the line. In the third part of the series Histoire(s) du Théâtre, Liddell confronts the theatre and a society that has lost its ties to spirituality and transcendence in favour of consensus. The title refers to the apex of Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan and Iseult, in which the two lovers can only find each other in Liebestod – love death –, and to the legendary torero Juan Belmonte. It was his trademark to fight dangerously close to the animal’s body, due to his deformed legs. Belmonte was never beaten, and eventually committed suicide. In the midst of a bullring, Liddell delves into all these figures and stories and calls up overwhelming images: the exceptional performance artist is both lover and beloved, bull and torero, enthralled by theatre and full of disdain.

26 / 27 May, 8 pm

Volkstheater

Spanish

German and English surtitles

2 hrs

Q&A

27 May, following the performance

Please note

Recommended for ages 16+

The performance includes self-harming acts.

Text, Direction, Stage design, Costumes Angélica Liddell With Angélica Liddell, Borja López, Gumersindo Puche, Palestina de los Reyes, Patrice Le Rouzic and Michael Anhammer and his son Clemens, Simon Brader and his daughter Nora, Lukas Elend and his son Béla, Thomas Mandl and his son Milo, Stefan Schweigert his daughter Romy Luise as well as Adrian Oshiake * Lights Mark Van Denesse Sound design

Antonio Navarro Matador tailor Justo Algaba Assistant direction Borja López Stage management Nicolas Guy, Michel Chevallier Lights management Sander Michiels Stage machinery Eddy De Schepper Set and costumes design Ateliers NTGent Dramaturgy of the project Histoire(s) du théâtre Carmen Hornbostel (NTGent)

Production management Greet Prové, Chris Vanneste, Els Jacxsens (NTGent) Communication and press Saité Ye, Génica Montalbano Production direction Atra Bilis, Gumersindo Puche Translation surtitles Snapdragon (English), Franziska Mucha (German) Surtitles Birgit Weilguny

Production NTGent, Atra Bilis Coproduction Festival d’Avignon, Tandem – Scène nationale (Arras-Douai), Künstlerhaus Mousonturm (Frankfurt a.M.)

executed by the team of the Wiener Festwochen | Freie Republik Wien

Premiere July 2021, Festival d’Avignon

* the final list of all participant extras can be found on festwochen.at

THE NEW YORK TIMES

ANGÉLICA LIDDELL’S HISTORY OF THEATRE

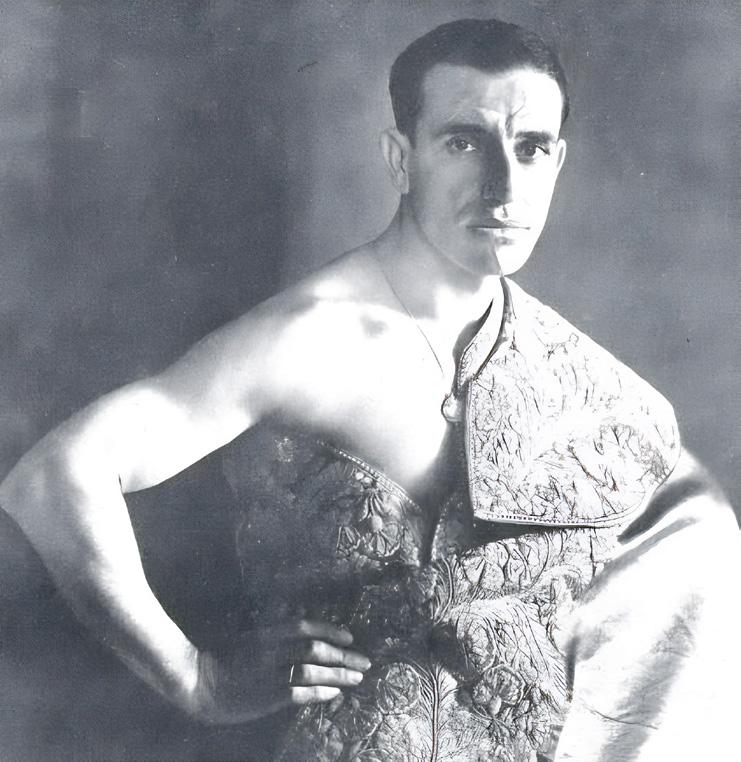

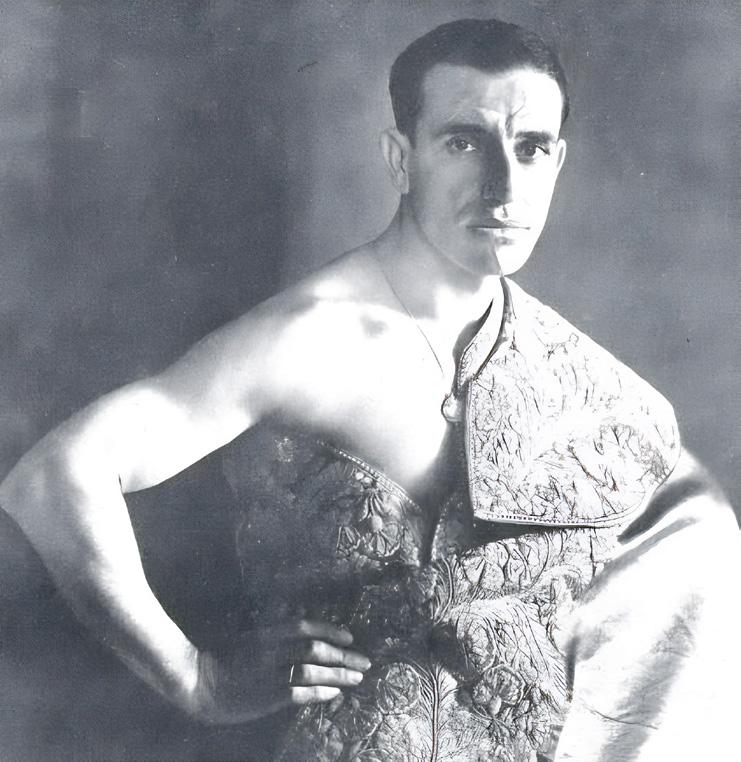

Juan Belmonte (1892–1962), the ‘divine stutterer’ from Seville, is considered to be the inventor of the spiritual bullfight. Going beyond an art, bullfighting was a spiritual exercise for Belmonte, elevating emotions into an infinite space, into eternity. His slightly deformed legs obliged him to develop a new fighting technique: upright and almost motionless, he fought dangerously close to the bull’s body and became the greatest matador of his time, in legendary competition with his rival Joselito, who died in the bullring. Belmonte’s assertion that ‘How you fight the bull is how you are’ sums up his philosophy. His suicide speaks of a sense of ‘no longer being able to live’ as captured by the philosopher Emil Cioran at the height of his own despair. Suffering from lung cancer, Belmonte took his own life with a pistol in 1962.

Liebestod, the title of the climax of Richard Wagner’s 1865 opera Tristan and Iseult, literally means ’love death’. The composer wrote the music for his own poetic rewriting of the medieval Celtic legend. The word Liebestod refers to the theme of the eroticism of death or of ‘love till death’, with the idea that the consummation of the couple’s love takes place in death, or even beyond it.

Angélica Liddell brings both references together: Belmonte’s tireless search for tragic beauty and sanctity, and Wagner’s tragic consummation of love in death. Where life is the tense and constant friction between Eros and Thanatos, Angélica Liddell’s theatre, and Liebestod more so than any other work, is a scenic poem. Liddell conjures up the figures of the bull and the bullfighter and is reflected in both: she is simultaneously the lover and the beloved, confronting her darkest abysses, her furious passion and longing for death, insulting her audience and contemporary culture, which has lost its connection to myth and transcendence in favour of reconciliation and consensus. Liddell herself and her texts, in which she screams, stutters and whispers at love and death, take centre stage. With visually striking references to a Spanish bullring and the rituals of the Catholic church, the production is structured like a rite of incantation.

IN CONVERSATION WITH ANGÉLICA LIDDELL

You speak of the emotion in Juan Belmonte’s work as a torero; are you talking about an absolute emotion that would be particularly perceptible in this art, which ceaselessly forces man to face his mortal fate?

Angélica Liddell The emotion in Belmonte’s work elevates consciousness to a sublime level. Emotion is the aesthetic supremacy of the torero. For Juan Belmonte, bullfighting is a spiritual exercise, to the point that he forgets that he has a body; that’s why emotions can reach the infinite spaces Pascal wrote about. According to Ramón Pérez De Ayala, the time of bullfighting ended with Juan Belmonte. Belmonte used to say that he fought bulls as he was and as he loved. He saw love and art, love and being, as one. Unfortunately, today’s lack of spirituality weakens all the arts, and not only the art of bullfighting. In art, tragedy has been replaced by the sense of duty, by democratic responsibilities, by social activism. We’ve confused the law of the State for the law of beauty, which means the end of art.

How would you define that emotion in relationship to you and to dramatic creation?

1

I understood I was looking for the same thing Juan Belmonte was: I’m looking for the sublime moment, for transfiguration, for overwhelming enthusiasm, for the blinding light, for this lyrical feeling that washes over you when you love.

A.L. After reading the biography written by Manuel Chaves Nogales and José Bergamín, I realised that I make theatre the way Juan Belmonte fought bulls. I’m talking about the intention and the shadows, the feelings, the intranquillity of the man from Triana1, this suicidal anxiety, this desire to die. I make theatre the way others fight bulls. There is a complete identification between the art of bullfighting and my way of being onstage. This unceasing quest for tragic beauty in expression doesn’t mean risking one’s life but giving all you can, fighting with death as an urge. I understood I was looking for the same thing Juan Belmonte was, I’m looking for the sublime moment, for transfiguration, for overwhelming enthusiasm, for the blinding light, for this lyrical feeling that washes over you when you love. I’m looking for the double dangers that echo in the depths of the soul. Sometimes I find them, sometimes I don’t. It’s not a question of will. You can’t will yourself into loving, nor can you will yourself into being a bullfighter, Juan Belmonte says. Will is for rehearsals. Once you’re onstage, all that remains is danger and transfiguration. An offering.

Triana is a neighbourhood in Seville famous for its toreros, its flamenco singers and dancers, and its artisans.

2 Ana Blanco Soto, known by her stage name Tia Anica La Piriñaca, was an incredible flamenco singer of the 20th century.

You write that bullfighters are writers in blood …

A.L. It’s from Friedrich Nietzsche. He says we have to write in blood, and we’ll find that blood is spirit. Pirañica2 used to say that, when she sang well, she could taste blood in her mouth. I always carry that image inside me, that way of expressing myself, that transfiguration. I talk to my ghosts. I let them possess me. I’m not an actress. Actually, I don’t like actors.

What is the place of bullfighting in today’s society? Is that art the symptom of the human quest for passion?

A.L. Today’s society is incapable of understanding torero because it is ice cold, empty, ignorant. It has no sense of beauty, and lacks the sensibility and intellectual and aesthetic refinement needed for bullfighting and its culture to be understood and practised. Our society is vulgar, mediocre, it strives for nothing but social and political consensus and has been impoverished by incentives that have led to the creation of a points system for culture, a culture of general interest rather than spiritual interest; it’s a society that favours stupidity over complexity, a society full of rights but without gods or rites, full of itself, without any conscience of the sacred. And bullfighting exists above all to give pleasure to the gods, just like theatre is a sacred space.

Is there a symbolic bridge between the end of a love and the death of the bull in the arena?

A.L. It has nothing to do with the end of love, it’s connected to the very essence of passion, to its climax, which is death. Love only becomes real in death. It’s in that sense that we could talk about a symbolic bridge between death from love (Liebestod ) and death in the arena: sacrifice and consecration, obeying to the end to the demands of something that is much larger than our own will.

In Liebestod, what form does the relationship between the story of Tristan and Iseult as told by Richard Wagner and that of Juan Belmonte take?

A.L. My plays are always conceived as crossroads, the place where you meet the ghosts of hanged men and those who have run away from the law. They’re created with the power of the unconscious. Juan Belmonte and Richard Wagner cross paths to talk about a history of theatre which is the history of my roots, of my depths. They cross paths to give voice to my darkness, to the origin of my plays. The sky falls and hell ascends to the throne of God. I’m not that worried about what will be understood; what worries me is what can’t be understood, the sense of wonder, of epiphany when faced with the inexplicable. What I’m interested in isn’t to reproduce reality but the real, that is, the invisible. That’s what the title says, paraphrasing Francis Bacon: the smell of blood does not leave my eyes.

Angélica Liddell is one of the most influential and important figures in performance theatre as an author, director and performance artist. She initially began her training at the Madrid Conservatory. Disappointed by her teachers and the institution, she dropped out and studied psychology and act- ing. In her radical physical theatre, she addresses personal, social and political violence and often uses Catholic imagery. For Liddell, art and life, writing and biography, poetic creation and theoret- ical reflection are one. Her theatre, which rejects conventional drama, deals with the darkest aspects of reality: death, violence and power, madness … The violence that is so explicitly expressed in her works takes on a mythological dimension, as it penetrates the depths of human existence and leads us directly to our most unspeakable instincts.

In 1993 she founded Atra Bilis Teatro and realised over 25 productions with the company, which toured worldwide and her plays have been translated into several languages. Liddell has received numerous awards for her plays and in recognition of all her work. Among others, she received the National Prize for Drama Literature in 2012 for La casa de la fuerza (The House of Force, 2012 at the Wiener Festwochen) awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Culture, the Silver Lion for Theatre at the 2013 Venice Biennale and was awarded Chevalier des Arts et Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture in 2017.

PUBLICATION DETAILS Owner, Editor and Publisher Wiener Festwochen GesmbH, Lehárgasse 11/1/6, 1060 Wien P + 43 1 589 22 0, festwochen@festwochen.at | www.festwochen.at General Management Milo Rau, Artemis Vakianis Artistic Direction (responsible for content) Milo Rau (Artistic Director) Text credits The interview conducted by Moïra Dalant in French in February 2021 for the 77th edition of Festival d’Avignon and translated by Gaël Schmidt-Cleach to English. Translation Monika Kalitzke Picture credit Cover © Christophe Raynaud de Lage; p. 4 portrait Juan Belmonte: Source: Wikidata.org, extracted on 18 May 2024. Produced by Print Alliance HAV Produktions GmbH (Bad Vöslau)

Main sponsors Public funding body

Media partner

Gastronomy partners

Main sponsors Public funding body

Media partner

Gastronomy partners

Main sponsors Public funding body

Media partner

Gastronomy partners

Main sponsors Public funding body

Media partner

Gastronomy partners