5 minute read

Balance and belonging: a recipe for wellbeing in international schools?

Angie Wigford and Andrea Higgins reveal the findings of a survey of 1,000+ teachers

What does wellbeing mean to the international school community? What promotes wellbeing and what are the barriers to it in this particular sector? Those were the initial questions upon which we based a survey entitled ‘Perceptions of international school teachers and leaders on their wellbeing and that of their students’. Over 1000 international school teachers from more than 70 countries responded to an online questionnaire which was followed up with 18 individual interviews.

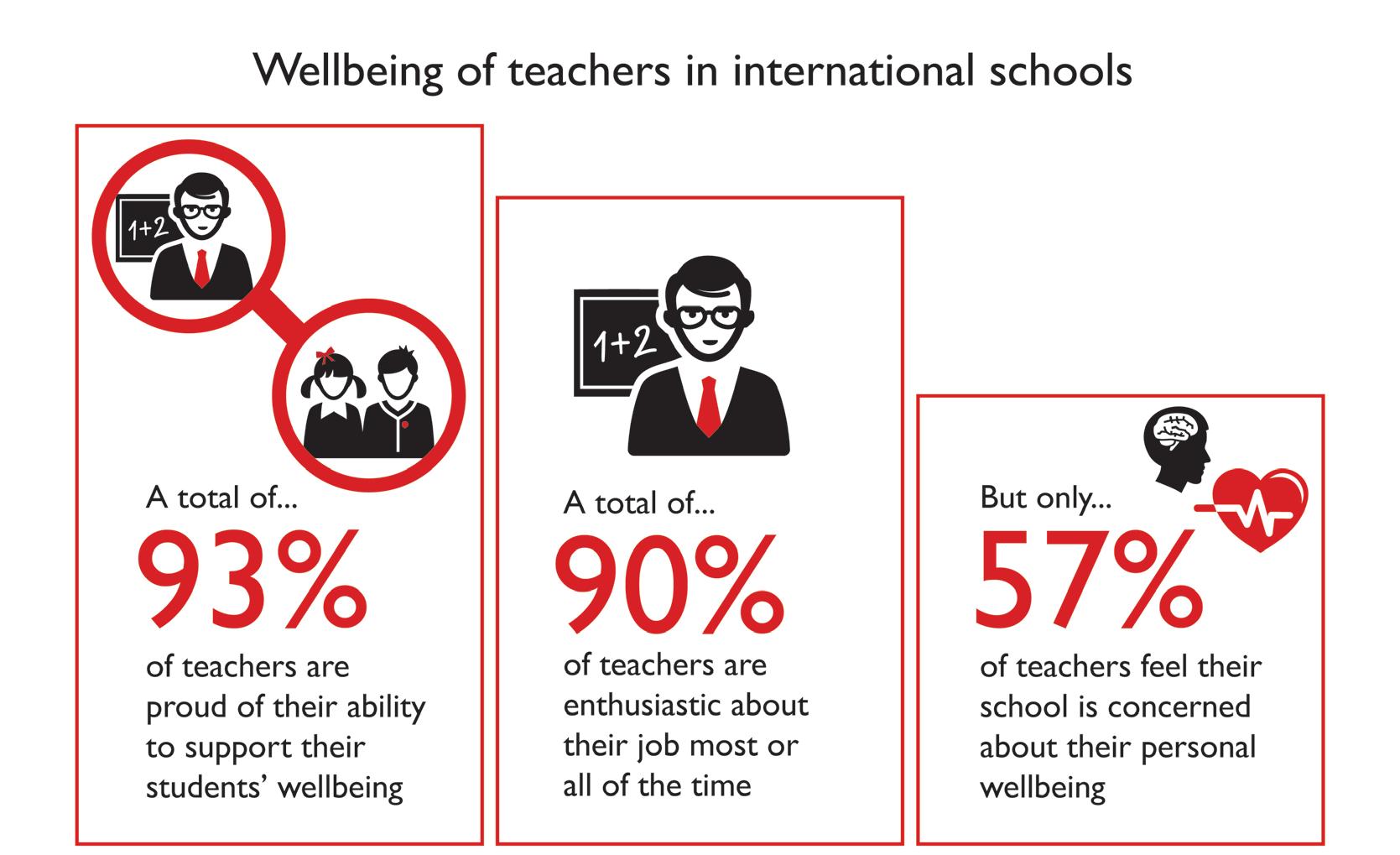

The overwhelming response was positive. For example, 90% of the international school teachers who responded said they found their work full of meaning and purpose for most, or all of the time; they were proud of their work and also proud of their ability to support their students’ general wellbeing. At first glance we were very excited by these results. When we delved deeper, however, a more complex picture emerged. We found it helpful to use the balance model of wellbeing (Dodge et al, 2012), whereby wellbeing is achieved when a person has sufficient resources (psychological, social or physical) to successfully address challenges in each area. This idea of balance is commonly

reflected in the literature on resilience and coping strategies (eg Lahad et al, 2013) which are closely related to wellbeing.

Key resources identified in our research were: supportive relationships, effective school support systems, robust communication and strong leadership. The challenges that stood out were the pressures of teacher workload, student workload, academic pressure and mobility (mainly in terms of transitioning between schools for both teachers and their students). Teachers really valued positive relationships with their colleagues, their students and even with parents. They talked about enjoying a sense of achievement, being able to make a difference and contribute to the community. Another key aspect of wellbeing for teachers was professional autonomy and being supported to explore creative and innovative approaches to their work. Teachers also reported high levels of student engagement, with friendships, belonging and being included as key features of their students’ wellbeing.

Challenges to wellbeing for teachers were around high levels of emotional pressure, and just under half reported ongoing frustration in their work. Many said that their school

was not concerned about their personal wellbeing. Teachers reported that their students’ challenges included: friendship problems, language issues, lack of sleep and high levels of stress (often due to academic pressure from school and parents).

Interestingly there were some indications of a consistent 10% difference in the perception of leaders to that of teachers, with the leaders being more positive. When this research was presented to a group of headteachers at a conference recently, there was an acknowledgement that it is the leaders who set the culture in a school, but in terms of wellbeing one group said ‘the behaviours and skills (around supporting relationships) are challenging to develop even if the knowledge and philosophy are aligned’. This recognises that enhancing wellbeing through promoting better relationships is something easier said than done.

Transitions in international schools have an impact and this came up as a key aspect of wellbeing, with experiences of induction and first impressions having a lasting effect. Teachers reported that their students were often significantly affected by moving school, leading to some students giving up on trying to fit in and not wanting to make friends for fear of losing them again. This factor in the wellbeing of students in international schools was identified long ago (see Fail et al, 2004) and continues to be a key challenge with varying levels of recognition, from some schools reporting pre- and postmove contact with annual follow-up to next-to-no support, as noted by one interviewee: ‘At this point we don’t have a strategy. We say ‘Welcome, here’s your uniform, here’s your timetable, let us know if you have any questions’’.

Also of concern to us has been an increased awareness, through recent discussions with school counsellors, that there is anecdotal but real evidence of self-harm becoming a common coping strategy for distressed students. There is a risk of self-harm becoming normalised and accepted by students. Schools need to address this but to do so is to necessitate talking about it, something many are reluctant to do.

In summary, we would argue that wellbeing for staff and students in an international school can be enhanced by

a focus on the concepts of belonging and coping. Many schools talk about having a caring community, and we would suggest that approaches that enhance belonging and develop emotional coping skills are an important part of that. In a place where a person feels that they are valued and part of a community, their ability to tolerate stress is enhanced and therefore their wellbeing more in balance. A community which supports individuals to develop good relationships and effective coping strategies is similarly more likely to demonstrate resilience at an individual and organisational level. It would be unrealistic to suggest that any one person or organisation can always have ‘good’ wellbeing; stress is a part of life and is often a helpful prompt. Our survey indicated that there are high levels of wellbeing in many international school communities and that a large part of this is based on the fact that there are high levels of psychological, social and physical resources helping to balance out the challenges.

References

Dodge R, Daly A P, Huyton J & Sanders L D (2012) The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222-235. Fail H, Thompson J & Walker G (2004) Belonging, Identity and Third Culture Kids: Life histories of former international school students. Journal of Research in International Education, 3(3), 319-338. Lahad M, Shacham M & Ayalon O (2013) The BASIC Ph Model of Coping and Resiliency: Theory, Research and Cross-Cultural Application. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Wigford A & Higgins A (2019) Wellbeing in International Schools, Available via www.iscresearch.com/resources/wellbeing-ininternational-schools