7 minute read

Interpreting the ‘international school’ label and the theme of identity

Heather Meyer explores what we actually mean by established terms and boundaries

In the most recent issues of International School, there has been an interesting debate on terminology and rhetoric commonly used within international school communities. The interest in the use of the label Third Culture Kid in these issues also highlights the ongoing significance of identity and belonging within international school communities.

The popular Third Culture Kid label and the title ‘international school’ have both become increasingly ambiguous as they become distanced from their contexts of origin. The term ‘international school’ today can be interpreted in a variety of ways, and holds varying meanings for different people around the world. I see this as a positive direction, however, as schools may become increasingly responsible for defining the term for themselves – weighing in on the extent to which they intend to interpret the label ‘international school’ literally or symbolically with respect to their individual ideological direction, and according to the requirements and expectations arising from the context in which the school is situated. As schools move towards an increasingly ‘global’ outlook, it is ever more vital to consider the extent to which locality plays a role in such ‘global’ frameworks and ultimately in the institutional identity of each international school. While literal interpretations of the term have led to a degree of homogenised practices and definitions, I argue here that employing a symbolic interpretation of the term encourages customised approaches towards establishing and cultivating institutional, community and individual identity.

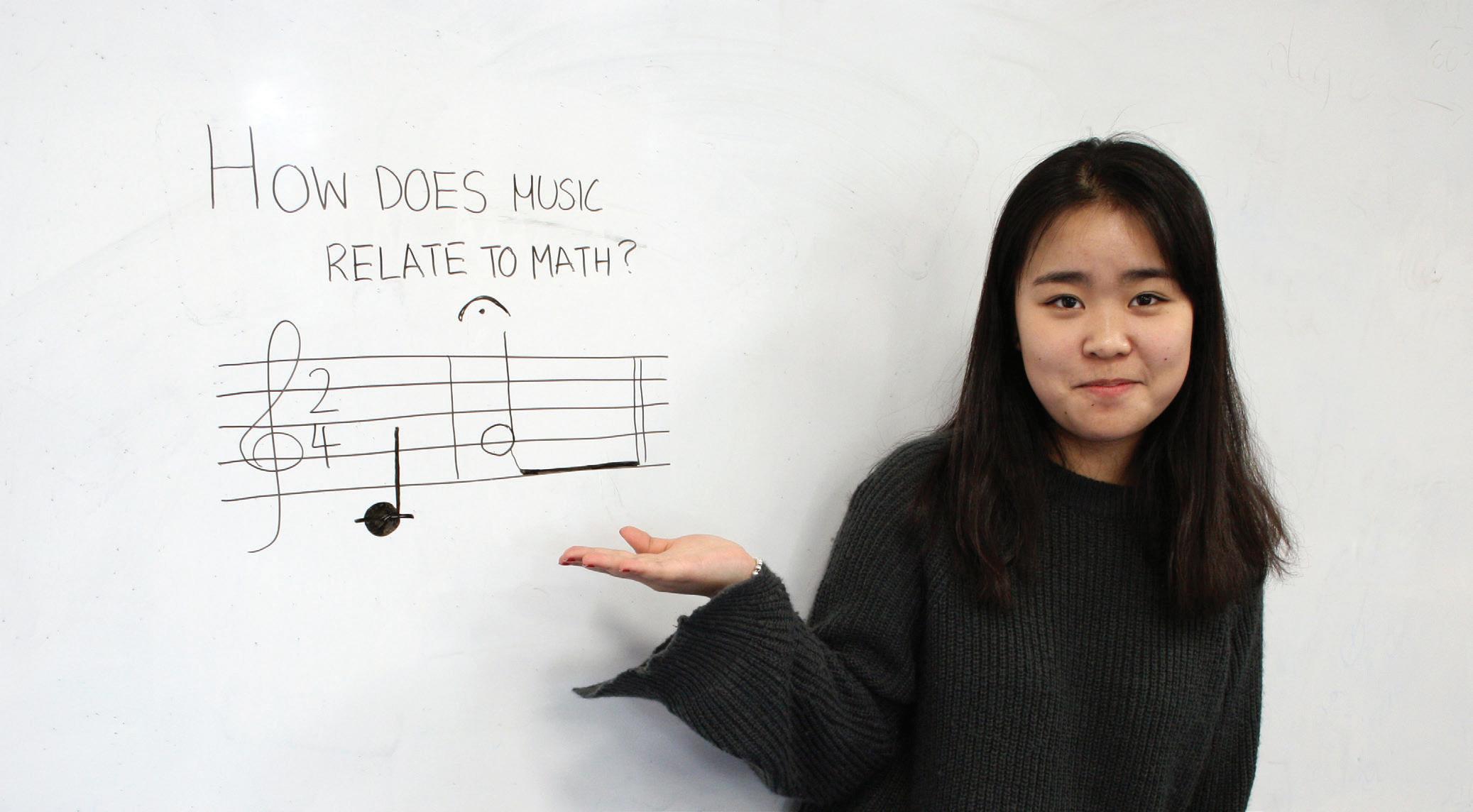

The term ‘international school’ in a literal sense foregrounds the culturally diverse community of individuals who represent different nationalities at the school, and who ultimately are the basis for the international school system. It reminds us of a world comprised of national boundaries which largely work to reinforce our similarities and differences – linguistically, culturally, ideologically, politically, socially, and so on. Thus when entering international schools, we see (and have seen for decades) similar imagery: a collection of national flags flying high representing many nationalities present at the school, and a conglomeration of national symbols beautifully showcased to demonstrate and support the title of the school. These visuals also hold a sense of cultural value to community members who identify with them. It is also not uncommon to find events within international schools that work to celebrate the inter-national makeup of the community – the literal coming together of many different nationalities. ‘Intercultural’ days for example have allowed members to represent and perform their nationalities – waving national flags, producing and consuming an assortment of national dishes, and dressing up in national colours and dress. These events not only contribute to the identity of the school as ‘inter-national’, but also help affirm a sense of belonging to (a) national culture(s) for participants.

These overt displays of national representation also come in more subtle forms, such as asking a child how they celebrate particular festivities in ‘their’ country, or creating nationality groups within parent-teacher organisations. While these opportunities are geared to empower community members and facilitate a sense of belonging, they also encourage ‘groupism’, which is a form of boundary-drawing and classification. In order to have groups, there needs to be an in-grouping (inclusion) and out-grouping (exclusion) process, even if it is subtle.

Nationality-based groupism reinforces a sense of national belonging and, by extension, a sense of nostalgia – it allows us to tap into our past and/or engage with culturally-relevant things with which we can identify and, even for just one moment, feel ‘less foreign’. At the same time, it provides a relatively ‘easy’ means to classify and group oneself and others: those who belong, and those who do not. Socially, it fortifies the habit of classifying others according to national background, and holds students, staff and parent community members responsible for cultural representation – reinforcing the notion that nationality is a central feature of ‘identity’. However as we all know, the cultural backgrounds and trajectories of international school students can be quite complex, fluid and particularly unpredictable.

There are therefore some significant tensions between establishing the school in the literal sense as an ‘inter-national’ learning space in which community members represent an array of identifiable nationally-oriented cultures, and in the symbolic sense – as a ‘global’ institution (however the term ‘global’ is to be defined). While the literal interpretation of the term ‘international school’ may lead to practices of groupism,

with all its positive and negative implications, taking more of a symbolic approach may push boundaries further on how ‘culture’ and ‘identity’ are conveyed, understood, and expressed in the school community.

Challenging the community to find cultural similarities with others that go far beyond national orientations is a way to encourage a more ‘global’ approach to identity and belonging: that individuals can be a part of many other cultures – football cultures, musical theatre cultures, educational cultures, business cultures, etc. This means continuing to create activities that encourage in-grouping across diverse social fields, and facilitating opportunities which encourage students to conceptualise their own identities as individual, unique, flexible, and thus ‘global’. This can be achieved through increased intercultural engagement with the host society in spaces outside of the international school, with charitable, sport, cultural and social (etc) events and activities. By engaging with this form of cultural diversity, students are able to conceptualise their world in a more complex and fluid manner. On an institutional level, perceiving and defining each international school as a ‘global’ learning space and community situated within a uniquely ‘local’ setting is beneficial to the positionality and identity of the individual institution. Localities can provide ample amounts of intercultural dialogue and exchange that extend beyond nationally-oriented frameworks. Engagement can be beneficial in establishing a sense of belonging and identity in relation to the host society on an individual level, but also on an institutional level.

Schools play an important role in the development of a child’s perception of the world: how they perceive themselves, how they perceive others, and the extent to which they draw boundaries between themselves and others. By extension, these practices of boundary production impact the ways in which students see themselves on a global scale – their aspirations towards future mobility; their perception of their own access to different cultures; and the conception of their position within the world as a ‘global citizen’. Encouraging and facilitating opportunities for students, staff and parents to establish a sense of belonging to cultures that are specifically not rooted through nationality-based groupism or representation does not entirely fit the literal sense of the title ‘inter-national school’. It does, however, follow closely the ideological or symbolic orientation for which schools are currently striving: that of creating global citizens.

Dr Heather Meyer is a researcher of international schools, based at Coventry University, UK.

Email: hmeyercoventry@gmail.com

IB PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPING LEADERS IN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

IB online workshops help you upgrade your teaching practice

Open to all educators in dozens of relevant, timely topics:

• Four-week workshops allow pacing that you control. • A fresh engaging module is introduced each week. • Collaborate with IB educators worldwide. • An experienced workshop leader guides your learning experience.

better student outcomes deeper understanding of IB pedagogy stronger confidence in your teaching practice greater ability to manage your teaching load