6 minute read

Inquiring together: student and teacher collaboration

Victoria Wasner talks us through an innovative ‘Change-Makers’ CAS project

What makes a good International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Creativity Activity Service (CAS) project? How can we learn to understand what ethical practice looks like, and how to carry out research in a more ethical way? How can we teachers act as role models in our embodiment of the attributes of learner dispositions and behaviours? How can we bring about change in our school environments? How can we facilitate student voice? What does ethical service learning look like and how are we going about it in practice? These were some of the questions that drove me to undertake a year-long collaborative inquiry project with a group of students at the high school where I teach, and where I have been IB CAS and Middle Years Programme (MYP) service learning coordinator for the past few years. The initial research question was:

How does meaningful teacher and student involvement as collaborative inquirers into service learning model a pedagogy for service learning?

In the spirit of IB CAS, service learning (Berger Kaye, 2010) and the mission and values of the IB, our project was planned to be collaborative (IB, 2015), democratic (IB, 2017) and to involve different inquiry cycles of action and reflection (IB, 2013). It was an attempt to model an educational practice that reflected my beliefs that pedagogy should be critical, responsible, risky, democratic and, ultimately, ethical. Researching as a teacher in practice, I also knew that I would need to respond to the context and practicalities of school life, adapting my methods as the project progressed and being flexible about where the project led.

Team Change Makers

After an open call to the whole cohort, 7 grade 11 girls came forward to participate in the project (see photo). It would have been easier in practical terms if I had simply worked together with my CAS group as timetable would have dictated; however, it was an important part of the inquiry that students had the option to take part, and in the name of choice and voice, we lived with the consequences of that decision. We named ourselves ‘Team Change Makers’, as the aim was to consider how we could work together to bring about change within our school.

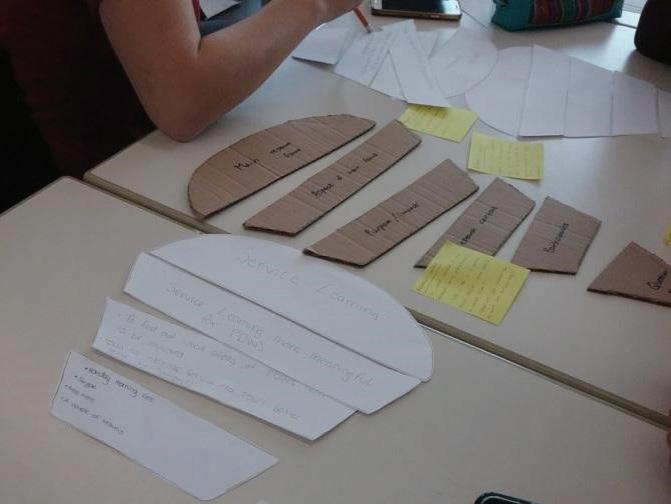

The year-long inquiry involved a process of eight different research cycles that were driven by my own practitioner questions and by questions that we developed together as the year progressed. As a group we met several times across the year, sometimes having in-depth discussions about the topic of service learning (cycle 2), learning about what it meant to carry out ethical research (cycle 4), how to collaborate with other teachers and get our voices heard (cycle 5) and how to share our knowledge and understanding with others in our school community (cycle 7). Individual interviews also captured student thoughts, and we used a virtual learning environment to reflect, make suggestions, give feedback and construct research questions. The girls also divided into two groups to conduct their own research with peers in other grades, after having designed their own research questions using an ‘ice-cream model’ technique (Brownhill et al, 2017). Figure 1 shows the girls using this model to define their questions.

Throughout the year, the students found themselves involved in different collaborative spaces beyond our Team Change Makers (TCM) group; they worked with teachers in a Professional Learning Community (PLC) entitled ‘Beyond

The Bake Sale’, they conducted interviews and focus groups with students in grades 9–12, and they prepared and led a student-teacher debate on the ethical nature of our school’s international service learning practice.

Authentic voice and meaningful collaboration

Whilst having learned research skills and how to act in a more ethical way as researchers, what the students really took away from the project was a sense that they were being listened to, that their voices were being heard, and that they had been able to contribute to a slow but gradual process of change in school practice. Reflecting back on the project at the end of their grade 12, what made the project meaningful was that they felt that they had contributed to some kind of change within our school. For the TCM girls, it was the feeling that they had somehow ‘made a difference’ that counted. They had felt empowered through having been listened to, and what mattered to them in the end was that they felt as though they may have left some kind of a legacy.

As teachers, as human beings, we can all have principles, but they are not enough; we need to do something with them, embody them and bring them alive through our collaboration with others. Student voice is ‘not something you switch on and off’ (Wall, 2018); rather it is a commitment to democratic principles of participation and the idea of pedagogical relationships within a personalist rather than functionalist approach to education (Fielding & Moss, 2011).

In terms of the IB Diploma Programme, I suggest that a CAS project is an authentic opportunity for students and teachers to work together as collaborative partners, and that an identified, context-bound need can be addressed if we consider our own school environments rather than being tempted to solve the world’s problems by looking much further afield. Outside of the IB Diploma, any such collaborative project could also be conceived if a school were to be interested in modelling principles of democratic participation and facilitating authentic student voice.

If students learn to value the efforts, the hopes and the ethical actions, underpinned by values, within their own learning communities, the more they will learn that a small act within a small community can be much more meaningful than an empty, detached act aimed at saving the world. Change is slow, but when we feel a sense of momentum and that we are being listened to, that is what gives us power to continue to hope and dream and allows our voices to emerge.

References

Berger Kaye C (2010) The Complete Guide to Service Learning: Proven, Practical Ways to Engage Students in Civic Responsibility, Academic Curriculum, & Social Action. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing Brownhill S, Ungarov T & Bipazhanova A (2017) Jumping the first hurdle: Framing action research questions using the Ice Cream Cone Model. Methodological Innovations, 10(3), 1-11 Fielding M & Moss P (2011) Radical education and the common school: a democratic alternative. Abingdon: Routledge IB (2013) What is an IB Education? Cardiff: International Baccalaureate IB (2015) Creativity, Activity, Service guide. Cardiff: International Baccalauerate IB (2017) What is an IB Education? Cardiff: International Baccalauerate Wall K (2018) Voice as a Catalyst for Effective Learning. Paper presented at the Fife Headteachers Conference.