10 minute read

Identity construction: fostering student agency

Niki Cooper-Robbins on practical ways to gather data around students’ own perceptions of their linguistic repertoire and ability

Allow me to begin by describing one of the worst moments in my teaching career. This is not the usual protocol when wanting to share good practice. However, without this incident, it’s unlikely that these developments would have transpired. Whilst supporting a young Arabic speaker with the reading of a simple story book, I employed the strategy of encouraging her through praise. Genuinely impressed with her progress, I commented on how well she was doing. She stopped, turned to me with the most frustrated expression, and said ‘But Arabic I read very good.’ My heart sank, and the realisation that students can have very different, often negative, perceptions of their own ability in a new language really struck a chord with me. My well-intended efforts to encourage her had been received as patronising and insensitive. With my proverbial wrist firmly slapped, I had been made acutely aware that language learning isn’t just a developmental process of acquiring skills. More significantly, it is also an emotional journey that has the potential to impact the wellbeing of a learner. From that point onwards, discussions and activities were factored into my lessons to broach this subject further. The motivation was fourfold: to help students celebrate existing strengths in their language repertoire, to emphasise the interconnected nature of languages, to understand the acquisition process, and to offer reassurance that although the frustration is normal, it will eventually pass.

In an attempt to understand better the behaviours of my students, I researched the concept of identity construction, rooted within the field of sociolinguistics and language ideologies. This area explores the relationship between language and identity. As outlined by Blackledge & Pavlenko, the key characteristic is that language and identity are a process of ‘ongoing construction, negotiation and renegotiation of identities in multilingual settings’ (2001:243). There are also societal influences determined by the ‘dominant majority group’ (2001:243) and this informs attitudes towards

languages and, in turn, language policy and pedagogy. The dominant language in an international school setting is more often than not the language of instruction, usually found at the top of the hierarchical pedestal in terms of status and prestige. One’s proficiency in that language can be used as an unjust marker to determine the social standing of community members, especially students.

Simultaneously, there can be an individual’s desire to identify with a society on the grounds of acceptance. The latter aspect moves into the realm of socio-psychology, as people strive to integrate due to a perceived sense of vulnerability and insecurity in a new language environment. Such pressures can be reinforced by parents, whose good intentions about their child becoming proficient as soon as possible in the school’s language of instruction often add to this burden and entrench misunderstandings around language acquisition. The need to dismantle this language hierarchy to foster a healthier, multilingual climate becomes apparent.

Dewaele & Nakano (2013) researched the notion of multilingual speakers feeling different when switching languages. For me, this became tangible when students presented their projects in their home language and English. From the marked differences in confidence, body language, depth of content and language usage, this confirmed the place and value of home languages in my classroom. To summarise, there are many emotions associated with language acquisition: my reading explained the observations made in the classroom, and confirmed my commitment to explore this further through the lens of social and emotional wellbeing. This initiative now underpins the languages philosophy and pedagogy implemented in my school context today, and this article shares some of the key practices developed to date.

To offer some context, the educational setting is United World College Maastricht (UWCM) in The Netherlands. The practices outlined have evolved over the last seventeen years, along with the school and its identity. As the English Language Learning (ELL) Coordinator, my role entails supporting the many students who arrive with little or no English at the primary, middle and high school. We do not select students based on their proficiency in English: to do so would disqualify many students from applying and would contradict the UWC mission. The upshot of this opendoor proficiency policy is a whole-school ELL department designated to serve the language needs of our students. With 115 nationalities, the school is a rich melting pot of linguistic diversity. Students’ need for social and emotional support, whilst learning the school’s language of instruction, remains the common denominator.

The practices outlined below range from community and small group to individually focused tasks, with the overarching purpose to raise awareness among students, teachers and parents as we strive for an environment where all languages are respected and supported. The school’s language philosophy and policy is the keystone to all of this work. Investing time to articulate the school’s standpoint on this forms a compass and reference point for all members of the community. Ensuring that this policy is well communicated is essential, and the following approaches have supported this process.

Offering reassurance and highlighting existing strengths through language badges

Language badges are the initiative of our Student Buddy Service group, born through our Youth Social Entrepreneurship programme where a team of IB Diploma Programme (DP) ELL students advocated for their language needs as equal members of our school community. These students support our newly-arrived high school students and help them to access our community as they transition into the new school and language. As translators in assemblies for leaders of Linguistic Diversity workshops offered to new staff, parents and students, this activity counts towards their Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS) commitment. Our community members are encouraged to wear their language badges for the purpose of celebrating our community’s linguistic diversity, and to make it easier to connect with people as we get to know each other. This activity also highlights controversial topics such as the use of flags to represent languages. Giving community members control over their badge design offers autonomy and plenty of conversation starters. A fun sense of competition also transpired among staff, and some of the more creative badge-makers found themselves commissioned to make badges for others!

Demonstrating the interconnected nature of languages, offering reassurance, celebrating existing strengths and understanding the language acquisition process through visual and tangible language profiles

This activity can be implemented using a range of materials and visuals. It can also be adapted to suit any age from kindergarten to high school. Its purpose ranges from raising community awareness about linguistic diversity, and creating a central display in the school in order to represent the languages in the community, to raising awareness of the individual’s transient linguistic profile and current strengths. As well as being included as one of the Linguistic Diversity workshop activities run by the Student Buddy Team, this also forms part of our language profiling activities when new students arrive. Community members are asked to draw their language profile using shapes. The larger the shape the greater the proficiency in the language. These spark fun and interesting discussions as we consider our profiles as individuals and as a group. This sets the tone for further dialogue and establishes a common language when we revisit this as part of our ongoing assessment practices.

An example of this activity with younger students, using pizza slices as an analogy

An example of a language profiling activity with a new student

Exploring the interconnected nature of languages and different language domains through body silhouettes

Roswita Dressler’s article (2015) inspired this activity. We are asked to consider where our languages are in our bodies and why we place them there, through real-time silhouettes drawn to scale (a great motivator for younger students!) to a simple silhouette drawn on A4 paper. This exercise facilitates discussion around language and emotion. It also raises awareness about the interconnected nature of our languages and their different purposes in our lives, and is an activity well worth revisiting at regular intervals to bring any subtle profile changes into consciousness.

Tracking language development over a period of time to offer reassurance and raise awareness of the language acquisition process

Inspired by Professor Paul Kei Matsuda’s keynote at the 2017 ECIS MLIE conference in Copenhagen with a focus on assessment and accountability, this activity helps students to observe their language development over a period of time. More specifically, it helps with the identification of which skills have progressed and areas for further development. The task entails a student selecting a current piece of work and comparing it with a previous piece of work completed earlier in the school year. In our context we use this as part of our portfolio and three-way conferencing practices because it helps students to find and provide evidence of their growth.

Raising awareness about the interconnected nature of languages, celebrating existing strengths and explaining the language acquisition process through skills per language activity

This activity is designed to help students to understand that their skills per language can differ and to help them to identify personal language targets. This can also contribute towards building self-esteem as students realise that their profile consists of skills that are already strong. Constructive dialogue can also help students to realise that these strengths have the potential to help them navigate their new languages.

An example of using scales 0-100 to ascertain a student’s perception of their language proficiency.

Parent Education Workshops to offer reassurance, to demonstrate the interconnected nature of languages and to raise awareness of the language acquisition process

Inspired by Eowyn Crisfield’s 2018 workshop ‘Parents as Language Partners’ at UWCM, we have revived our parent workshop practices and now host a number of workshops throughout the year. A key aspect of these workshops is empowering parents to map out their child’s language pathway by identifying which languages will be developed and for which purposes. For this to be a successful partnership, understanding parents’ expectations is fundamental so creating opportunities for discussion is key. These activities now form part of our parent feedback practices where the parents have the opportunity to

share their own expectations, having seen their child’s expectations in the portfolio. This information can be used to inform the succeeding three-way conferences and new language goals established in collaboration with the parent, teacher and student. An example of a parent feedback form in response to the child’s expectations An example of a student’s expectations

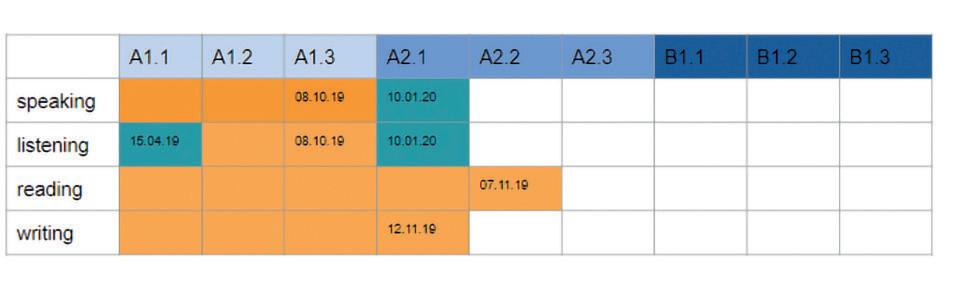

Understanding the language acquisition process by naming it

In our context we use the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) when assessing a student’s language proficiency. To avoid this language being reserved for report cards and as terminology between adults, this process has been visualised and is used as a reference point when discussing the skills with students. Over time, students become familiar with the terminology and make reference to it themselves. It offers reassurance that progress is being made and it also manages expectations that language

learning takes time and investment. A visual breakdown of a student’s language profile (A1-B1 range) using assessment data following a request from a Year 4 student.

To conclude, the implementation of a wide range of activities has helped us to adopt a more holistic mind-set towards languages in our community. It remains a work in progress. We continue to strive for a place where linguistic diversity is utilized and celebrated, where the interconnected nature of languages is nurtured, and where the language acquisition process is understood. Most significantly, the agency demonstrated by the students through these activities has taught us that a healthy multilingual environment can only be truly established when the social and emotional wellbeing of its language learners is acknowledged, supported and prioritised by all members of its community.

References

Blackledge A and Pavlenko A (2001) Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. International Journal of Bilingualism, 5 (3), 243-257 Dewaele J-M and Nakano S (2013) Multilinguals’ perceptions of feeling different when switching languages, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34 (2), 107-120 Dressler R (2015) In the classroom. Exploring Linguistic Identity in Young Multilingual Learners. TESL Canada Journal, 32 (1), 42