7 minute read

High Performance Learning: Building the cognitive competencies that we know lead to high performance

Though traditionally we have assumed that high performance for all students was an impossible pipe dream, now it seems it could be possible – so in forward-looking schools this ambition will inevitably shape their work. Of course many teachers still think that everyone doing well is impossible, and that they are doing as well as they can – given the class they are teaching. But it is worth remembering that there was a time in the past when educators thought girls could not achieve as highly as boys. We thought it was genetic because that’s what most psychologists believed. We also thought that students working in a second language would be unlikely to do as well as their monolingual peers. And

we thought that dyslexia and dyspraxia would inevitably limit a child’s educational progress. Well, life has certainly proved otherwise. Girls are outperforming boys in school. Multilingualism is now seen as an asset rather than a problem, and individuals with dyslexia and dyspraxia are at the top of various professions.

Yet in many schools, despite all research evidence to the contrary, it is still assumed that the majority of students are incapable of achieving highly. Recent research in leading international schools (Glass, 2019) found that more than 60% of teachers felt that they had students in their classrooms who are not capable of high performance. They, like many others, still see their students as having a certain level of ability and refer to them accordingly – as less able, more able, for instance. Of course many of these teachers have already accepted that innate ability does not account for everything. They are familiar with the nature vs nurture arguments, and have accepted that factors such as environmental context and family background can play a part. Some have even adopted Carol Dweck’s (2008) Growth Mindset ideas. But the key point is that while they recognise these features, many teachers stay wedded to the idea that they are merely additional or even marginal factors. In the end they still believe that you either have what it takes to succeed in school or you haven’t. Hence we expect our exam outcomes to largely reflect the bell curve of ability rather than assume that high achievement could be the norm in our school.

Research shows, however, that intelligence is one of the least inheritable traits as it has no obvious genetic link (Rietveld, 2013). Throughout a child’s lifetime, as a result of their experiences, changes to DNA occur and it is these that determine a child’s skill development and intelligence levels rather than their birth genes. When we ensure that students have the right learning opportunities, the right support and the self-belief that they can achieve highly, then most of them do. Research from a whole variety of directions indicates this. Why is this and why didn’t we know this before? Well, neuroscience tells us that the brain is exquisitely plastic and can be developed (Jaeggi et al, 2008). So it’s not a case of either born to succeed or born to fail. We can build intelligence, build new neural pathways. And not just a little growth. High performance really can be the standard and the norm in your classroom and in your school.

Of course, building brains is not all straightforward. The journey for some is more difficult. Like driving, some will take longer to master it and pass the test – but that does not indicate how good their driving will be in the longterm. Teachers must move away from easy work for some or lowering the cognitive bar at the first sign of failure; just a redoubling of efforts and exposure to different types of opportunities is what’s required. It’s not ‘I can’t’, it’s just ‘Not yet’. Building self-belief in students is step one in building brains. But merely believing that everyone has the potential to become a high performer doesn’t make it happen. You don’t become a top athlete just by believing you could be one. If we want the vast majority of students to do well then we need to systematically build cognition, and that means focusing teaching on developing not only ways of thinking but also learner behaviour and values and attitudes.

Fortunately we know a lot from research about how the most successful learners think and learn, and it is this that we need to replicate if we are to deliver high performance for the many rather than the few. We need to optimise our teaching and learning so that everyone can do what high attainers have always done intuitively. What is more, we need to use contemporary research evidence to do this, and not only to rely on evidence from the past. While taxonomies such as Bloom’s Taxonomy were good for their time, research into cognition has moved forward a long way in recent years and these taxonomies no longer represent the state of the art.

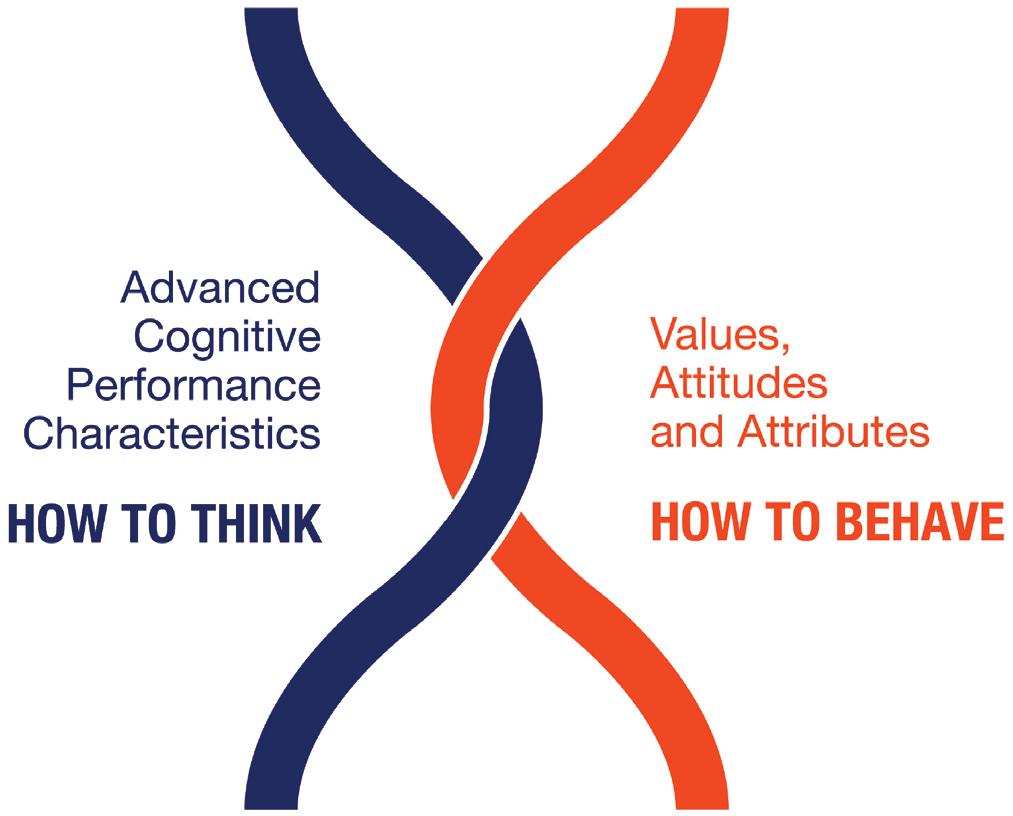

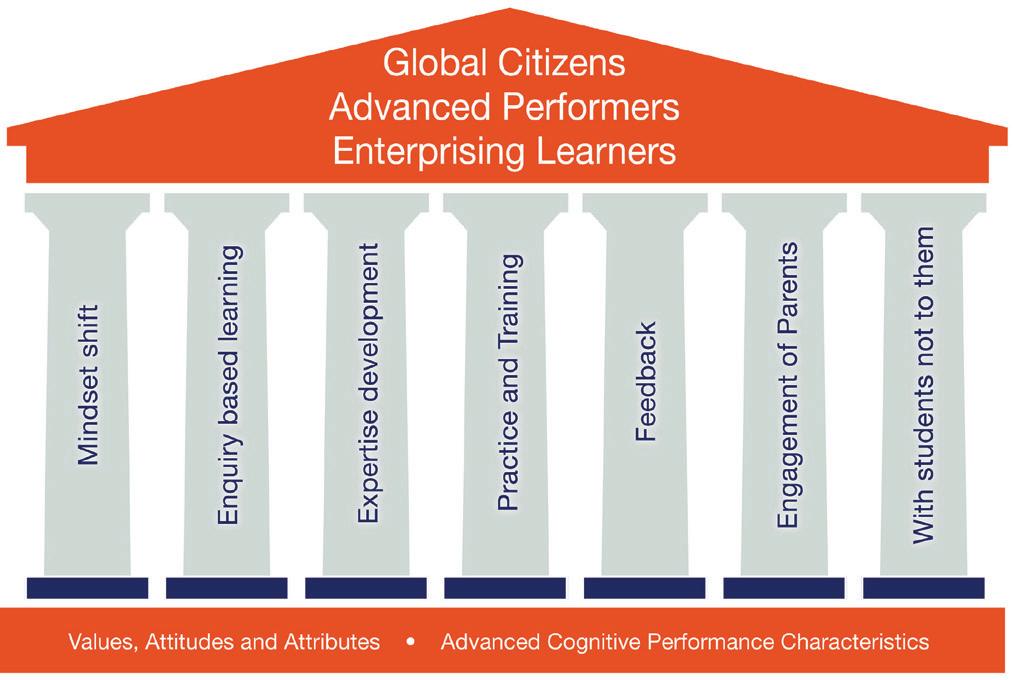

What we know from a meta-analysis of the research into how the most able think and learn (Eyre, 2016) is that there are a set of cognitive competencies that really make a difference: 20 that relate to thinking (Advanced Cognitive Performance Characteristics) and 10 that relate to learning and life behaviours (Values, Attitudes and Attributes). These can be clustered into 8 sub-sets. Successful learners are beyond the novice stage on most of them but none of us master them all to the expert level. As the individual student starts to progress through the 5 levels from novice to expert they gain both capability and intellectual confidence, and that is what helps them to succeed.

Helpfully, most teachers will almost inevitably be doing some of what is necessary already, so this is not a case of starting from scratch so much as being much more disciplined and systematic. If we want success for everyone, not only those who catch on fast, then we need to ensure that we build all of the high performance learning (HPL) competencies via our teaching, and do so more deliberately and more frequently. That way students will have enough practice to give them a strong chance of gaining mastery. We also need to draw students’ attention to them so they see their importance.

Furthermore, if competency building forms the backdrop of your teaching then it helps to make the intentions visible to students. Competency development is not optimised if you hide it away. It needs to become the language of the classroom, and to have real effect it becomes the language of the entire school, visible around the school and talked about and valued by every teacher, by the students and by their parents – starting as young as possible.

The building of these crucial HPL competencies is made easier by working in ways that naturally embed them into day to day practice, ways that promote independence of thought and mastery of the subject rather than merely preparation for the next assessment point. The 7 Pillars of High Performance Learning capture some of the key vehicles which support the development of the HPL competencies. Each pillar is significant in itself and has a unique part to play, but it is when the pillars work in harmony that we start to see amazing results.

When in 2010 my research into high performance learning was first published, cognition was not in fashion in educational circles. Now however, with rapid strides in neuroscience and the wider learning sciences, cognition is starting to be recognised as the key to educational performance. The field of learning science is growing, and schools are moving away from data-driven school improvement and towards data-informed self-improving schools with learning at their heart. At the same time we are discovering more and more about how our genetic make-up develops and the sense of possibility this offers. So we know what is possible and we know how to make it possible. International schools have a unique opportunity to explore this new world without constraints from government, and professional learning communities in reflective international schools are discovering that education can, and should, expect more from more.

References

Dweck C S (2008) Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books. Eyre D (2010) Room at the Top: Inclusive Education for High Performance. London: Policy Exchange. Eyre D (2016) High Performance Learning: How To Become A World Class School. London: Routledge. Glass R (2019) Even the best can be better: Could your staff attitudes towards students be holding you back? Oxford: High Performance Learning (www. highperformancelearning.co.uk) Jaeggi S M, Buschkuehl J J and Perrig W J (2008) Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105(19):6829-33 Rietveld C A et al (2013) GWAS of 126559 individuals identifies genetic variants associated with educational attainment. Science, 340:1467–1471