ATLAS

DWELLING MONUMENTS

Shapes In Landscape Goals For The Trip Wounded Landscape 1 28 38 5 29 47 9 39 57 61 Tarva Frøya Storfosna Hemnskjela 69 Play Of Shadows Case Study Details Reflections

TABLE OF CONTENT

GOALS FOR FIELDTRIP

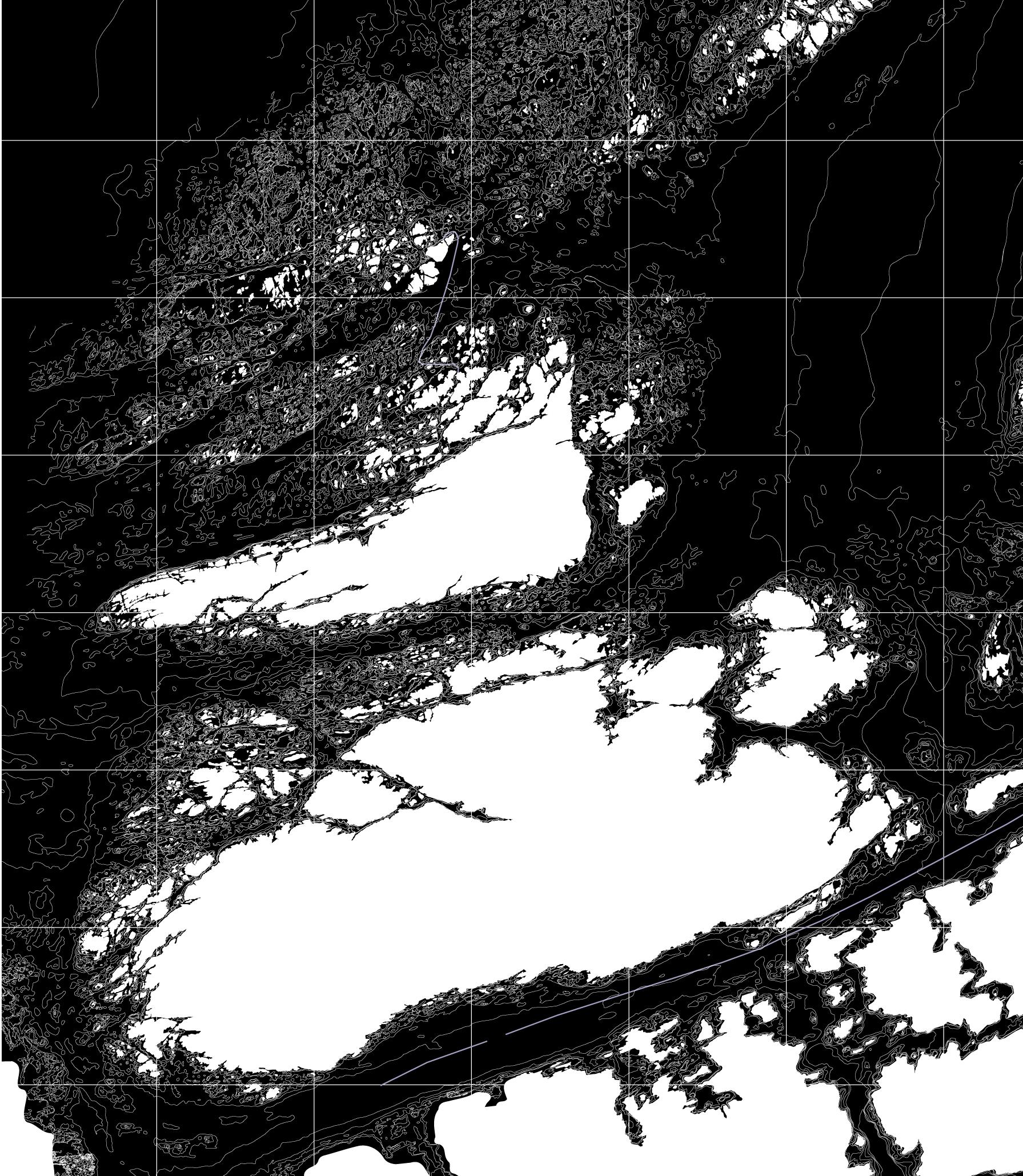

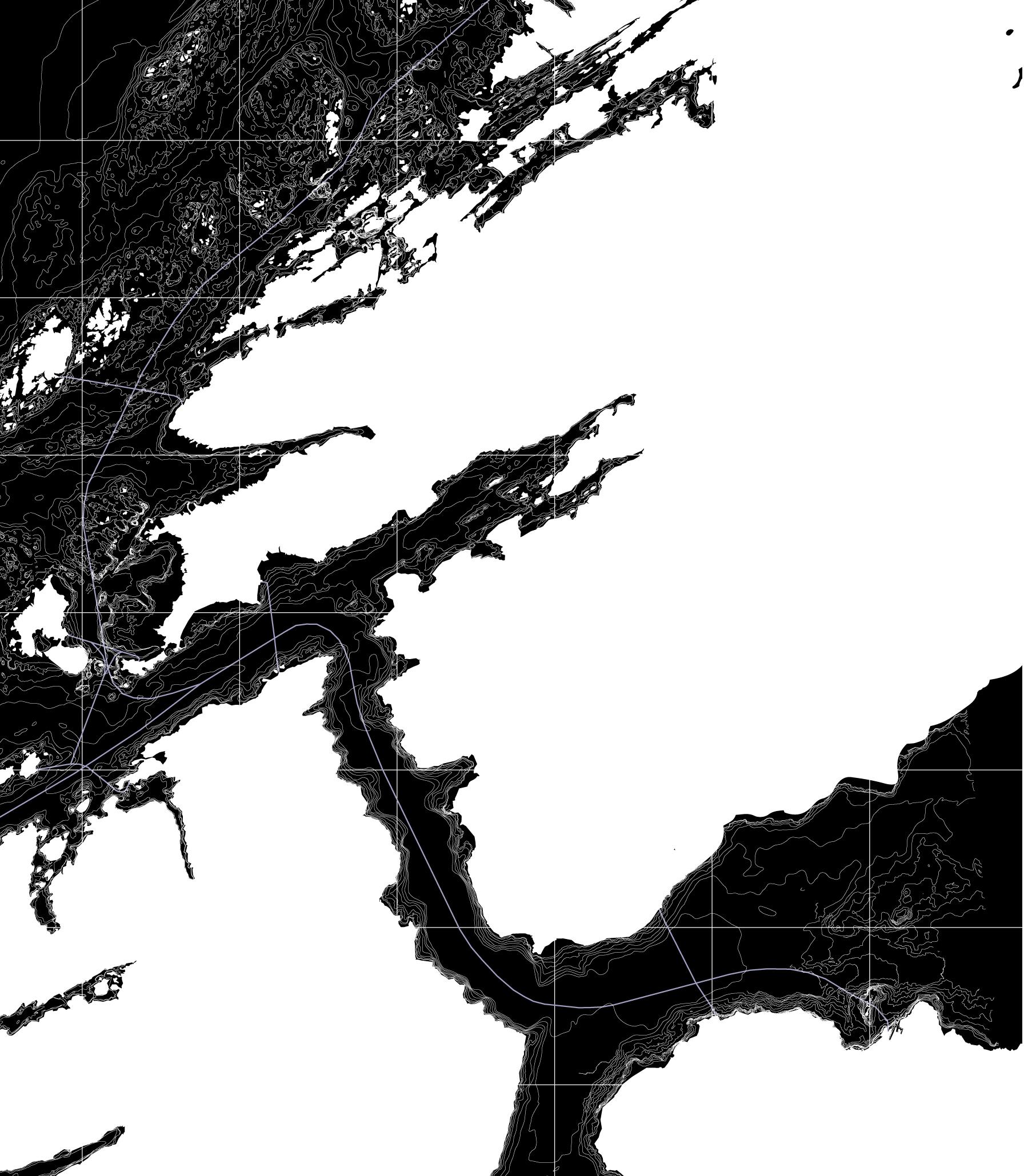

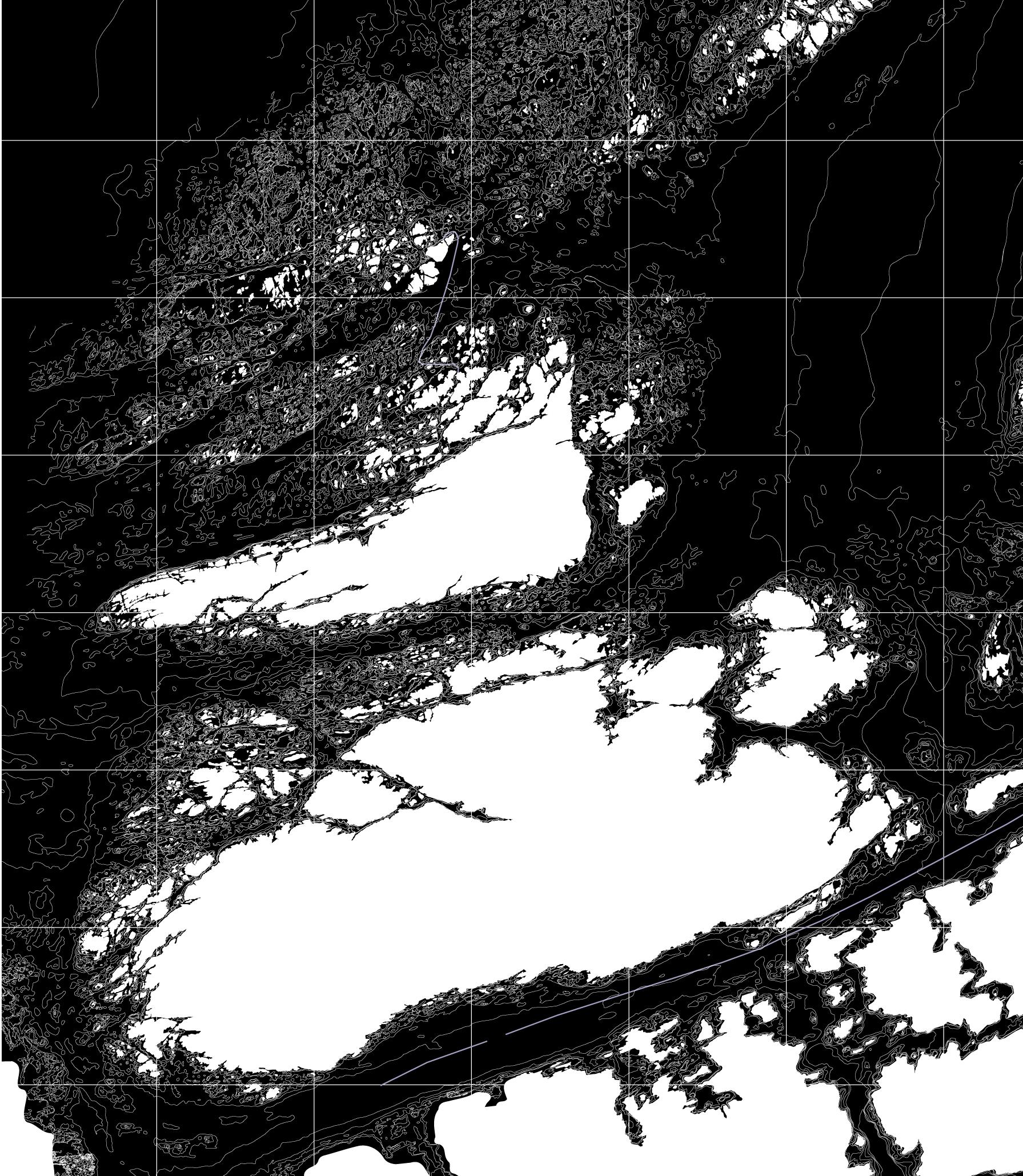

We wanted to start our semester by exploring bunkers. The decision fell on traveling throughout Trondheimsfjorden, a strategically important location for the Germans after the occupation. Trondheim was to become “Nordstern” (Neu Drontheim) a new German metropolis functioning as the main naval base for patrolling the Atlantic sea. Although the large plans for “Nordstern” never were completed, the fortifications protecting the mouth of Trondheimsfjorden were they are still riddling the coast today. The bunkers we visit were separated into groups; “Artilleriegruppe Drontheim-West”, “Artilleriegruppe Drontheim-Ost” and Artilleriegruppe Orlandet” in charge of defending the approach to Trondheim.

The goal for the trip was to register and measure different kinds of bunkers. Presenting the diversity of fortifications, while investigating proportions, construction, detailing, their relationship to the landscape and their history. We wanted to broaden our knowledge of the bunkers by experiencing them, their material, how they interact with the light, how they would have functioned and what it feels like to inhabit them. By doing this, we could get a better sense of the opportunities that lie in these structures.

1

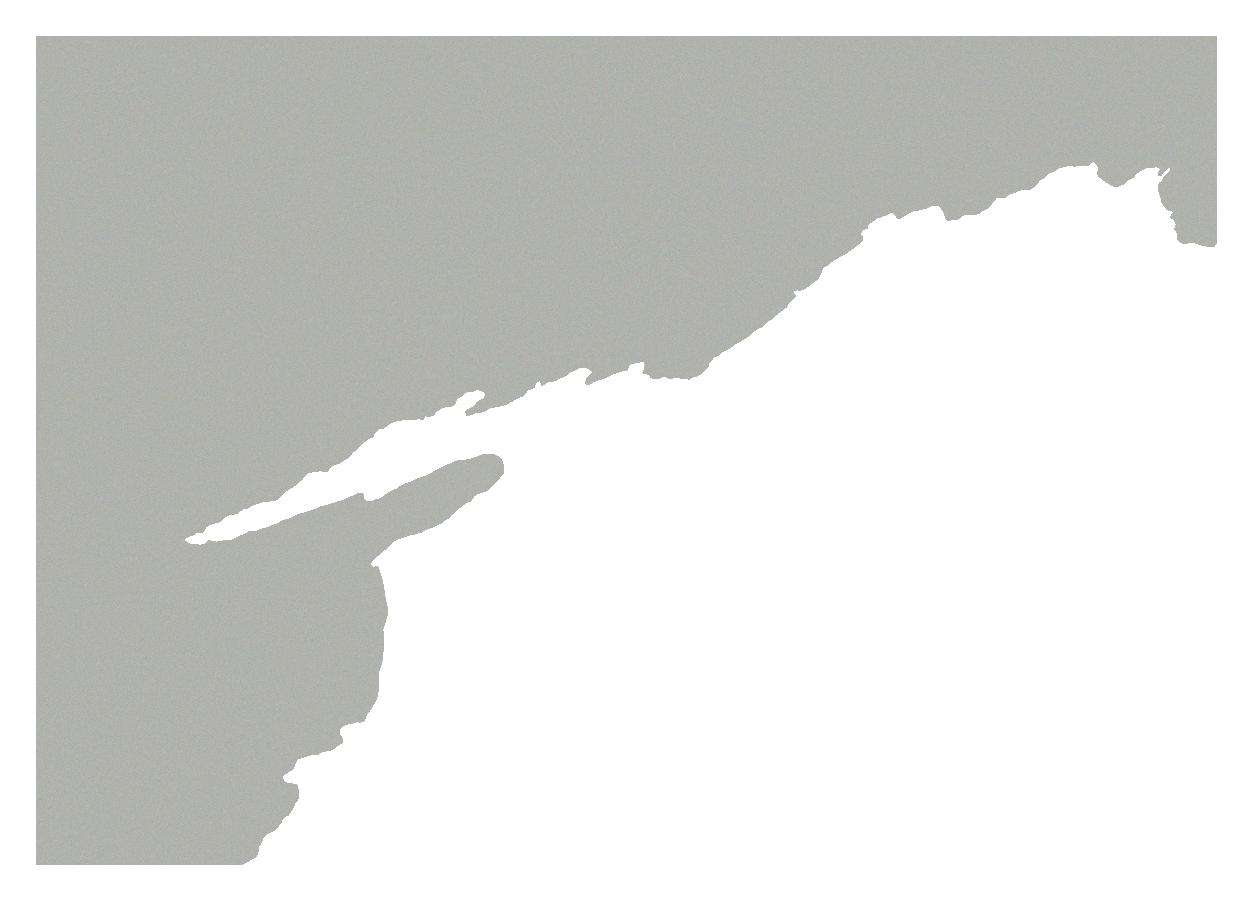

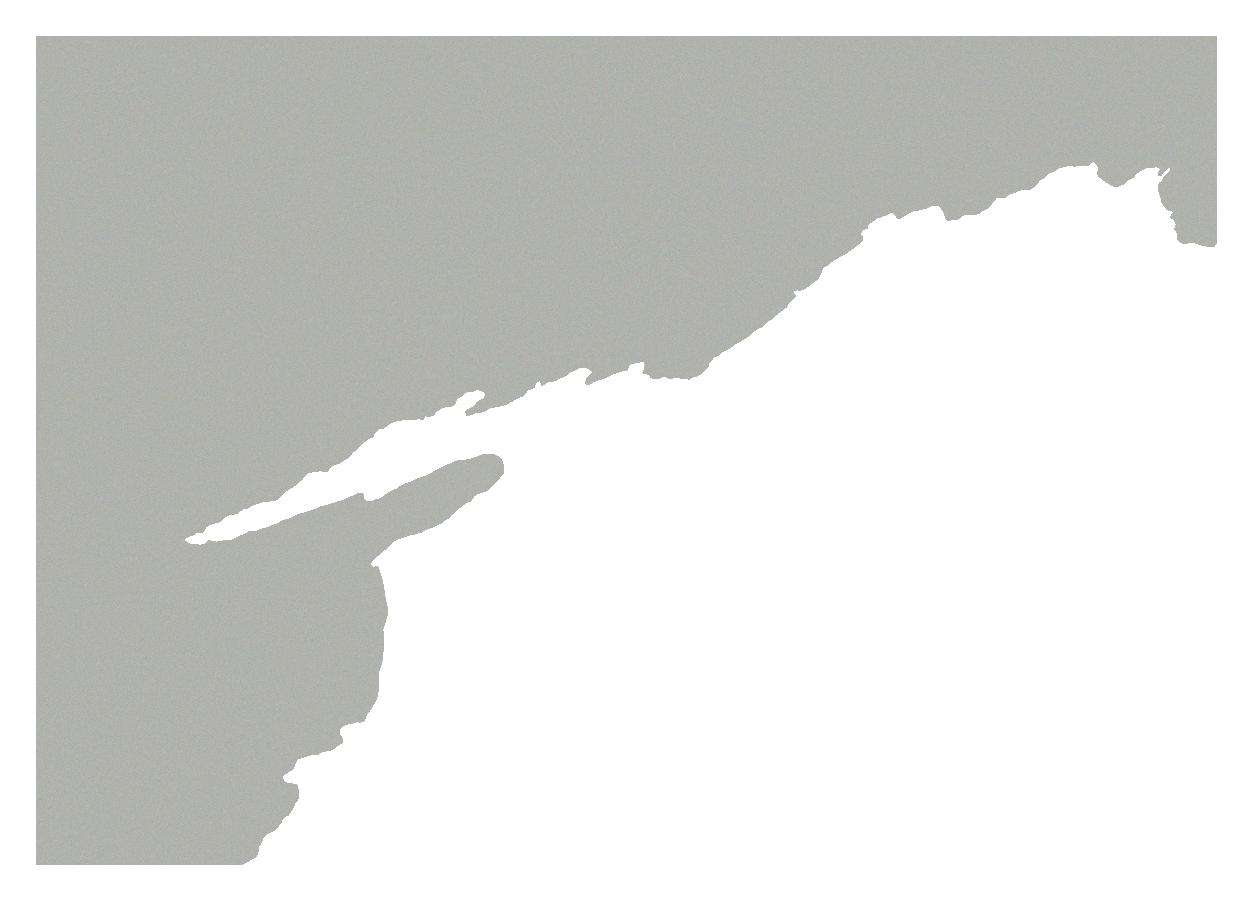

3 HEMNSKJELA STABBEN TARVA STORFOSNA LEKSA Visit Visit 2 Days 4 3 Days

4 TRONDHEIM TARVA STORFOSNA BREKSTAD HYSNES SØRVIKNES HAMBÅRA Visit 1 Day Start 1 Day Visit Days Days

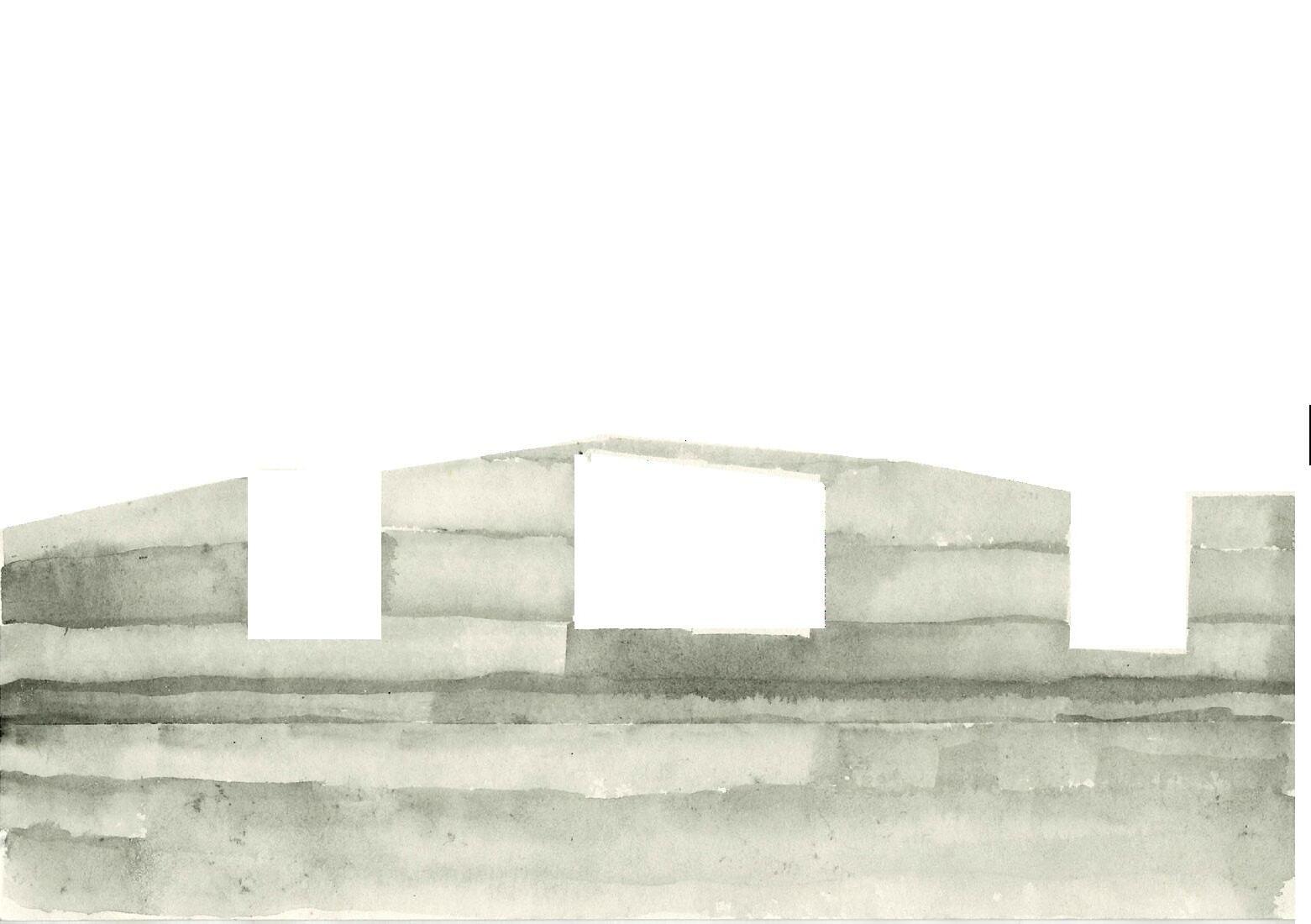

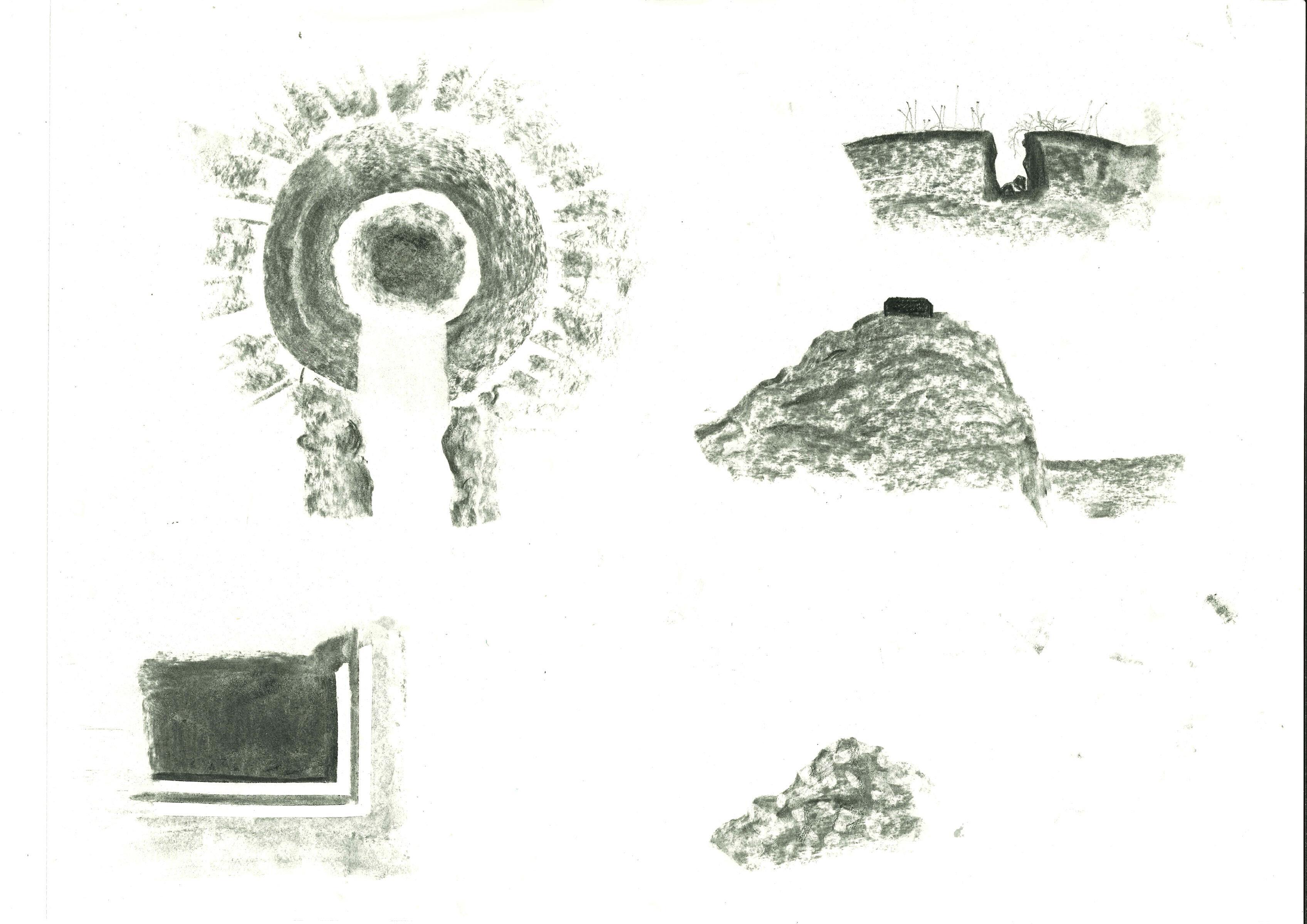

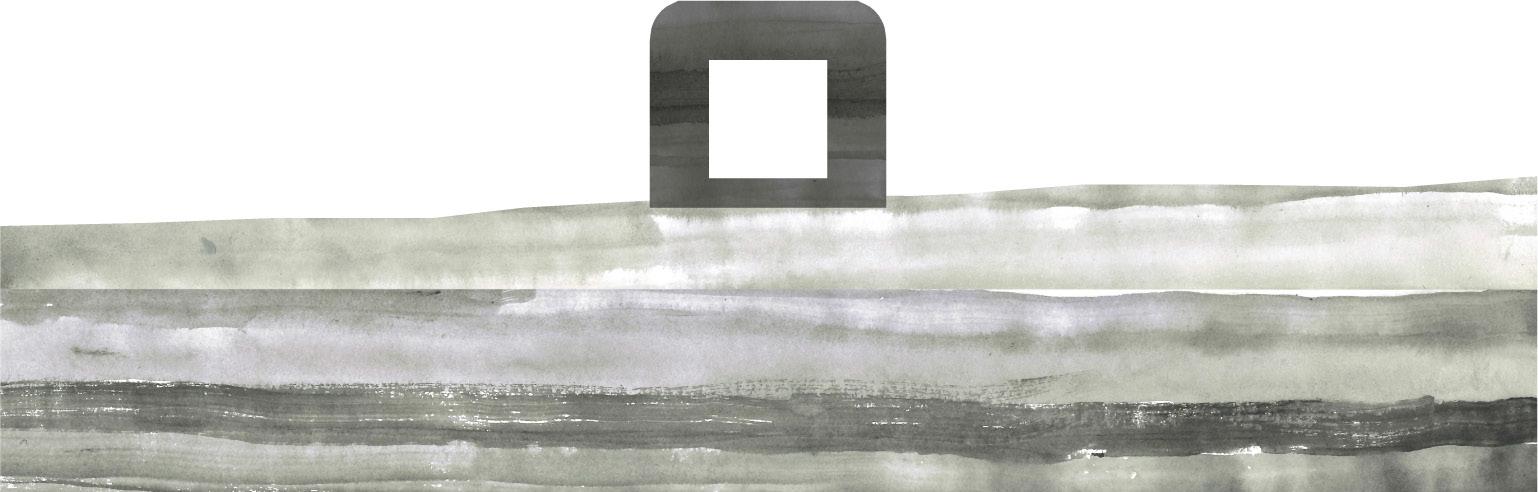

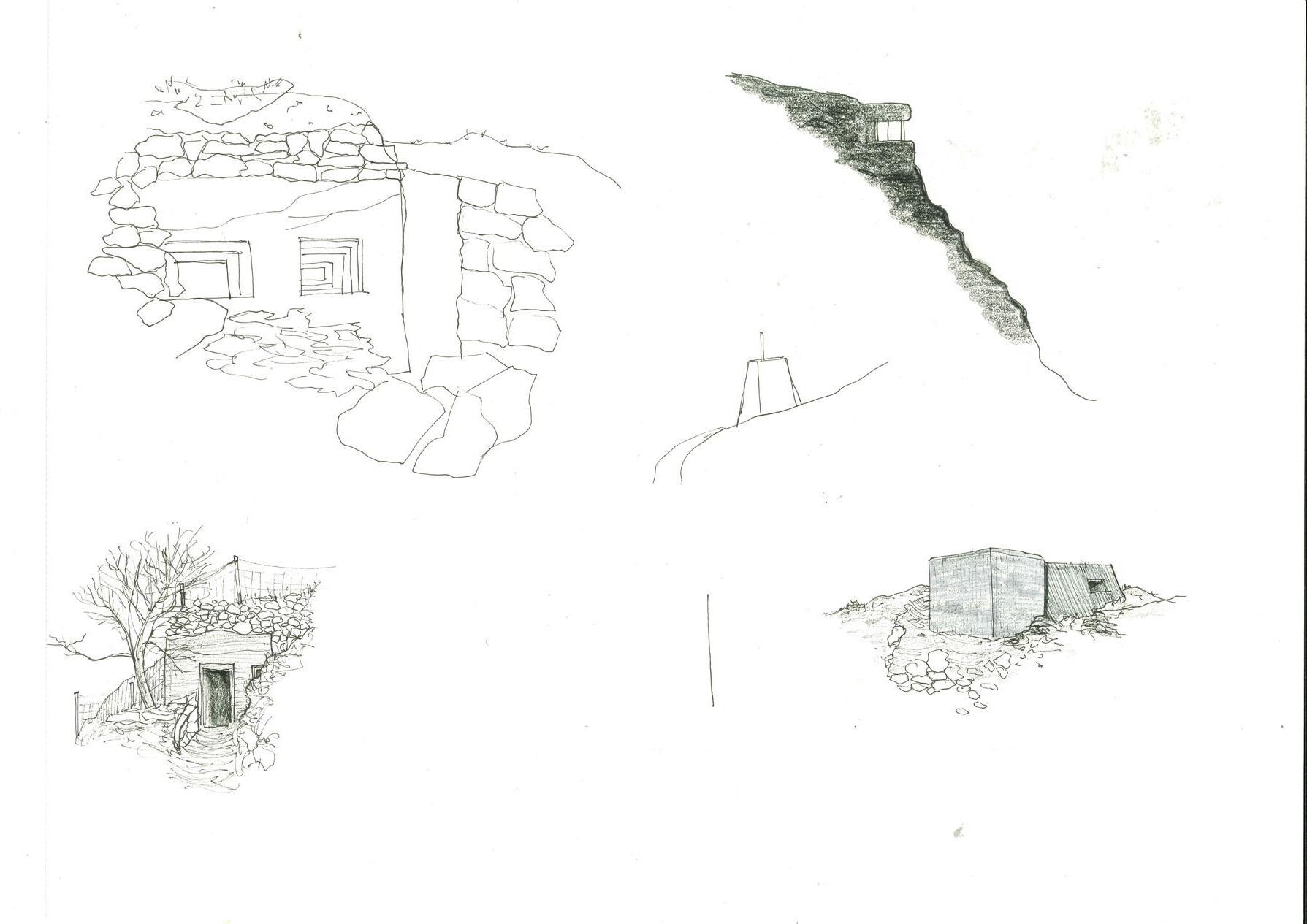

SHAPES IN LANDSCAPE

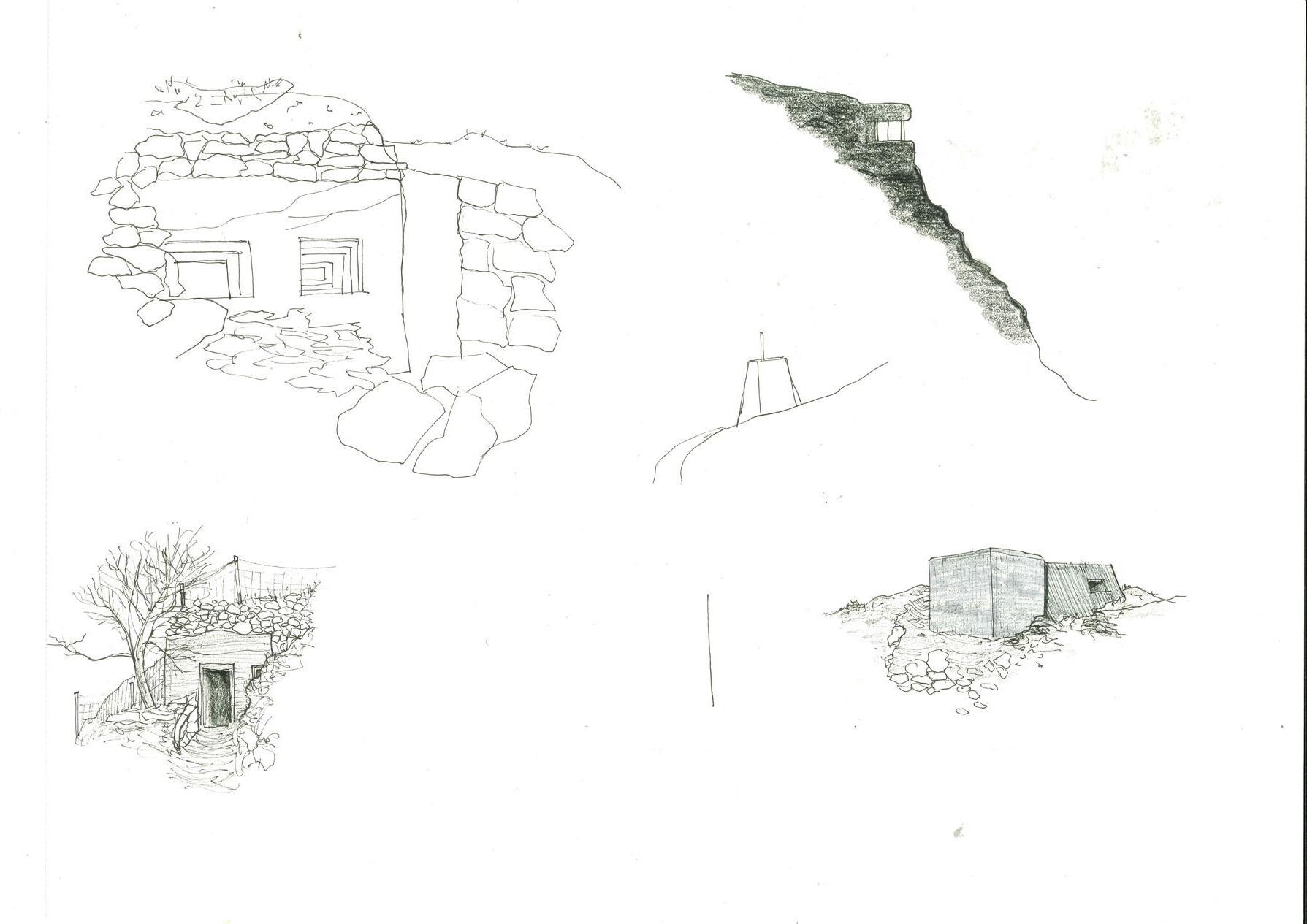

The concrete structures are joined to the landscape, shaped to the landscape. It has changed the landscape and even if a sensible and easy way could be found to remove them, they will take a piece of the landscape with them. The structures have become part of the landscape, like a storytelling layer embedded in the ground; clearly illustrated by the many tracks and trenches that today lie like open wounds in the terrain.

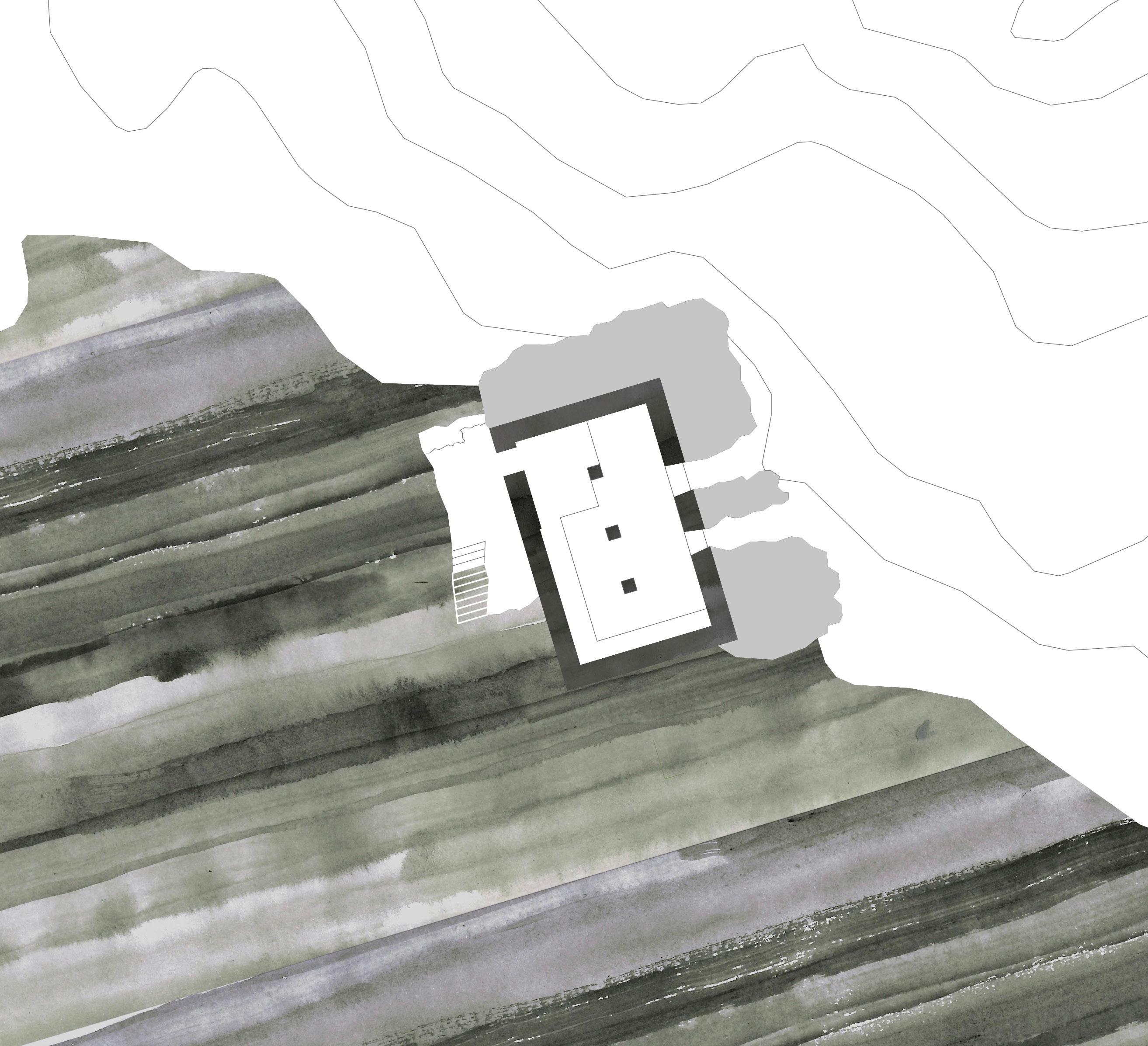

Site adaptation, a known term for most modern day architects. It expresses how the architecture we build fits into its natural surroundings, but how do we define this? Is the term related to the fact that buildings should perform their function in interaction with the landscape? Could one say that the bunkers are site-adapted? The structures relate to the landscape, carefully measured and positioned concrete walls favorably so that the building does not protrude out of the terrain, hidden between the rocks they cling to the landscape. Is it possible to argue that this is a form of tactical site adaptation; an adaptation that contrasts with current thinking about site adaptation in architecture as a tool for minimizing the impact of the built environment placed on nature and landscape? The bunkers were not placed there to enrich the landscape, rather to exploit its potential for camouflage and protect the buildings. Nevertheless, a relationship is formed between the structures and the landscape. The positioning and intervention of the bunkers in

5

6

7

8

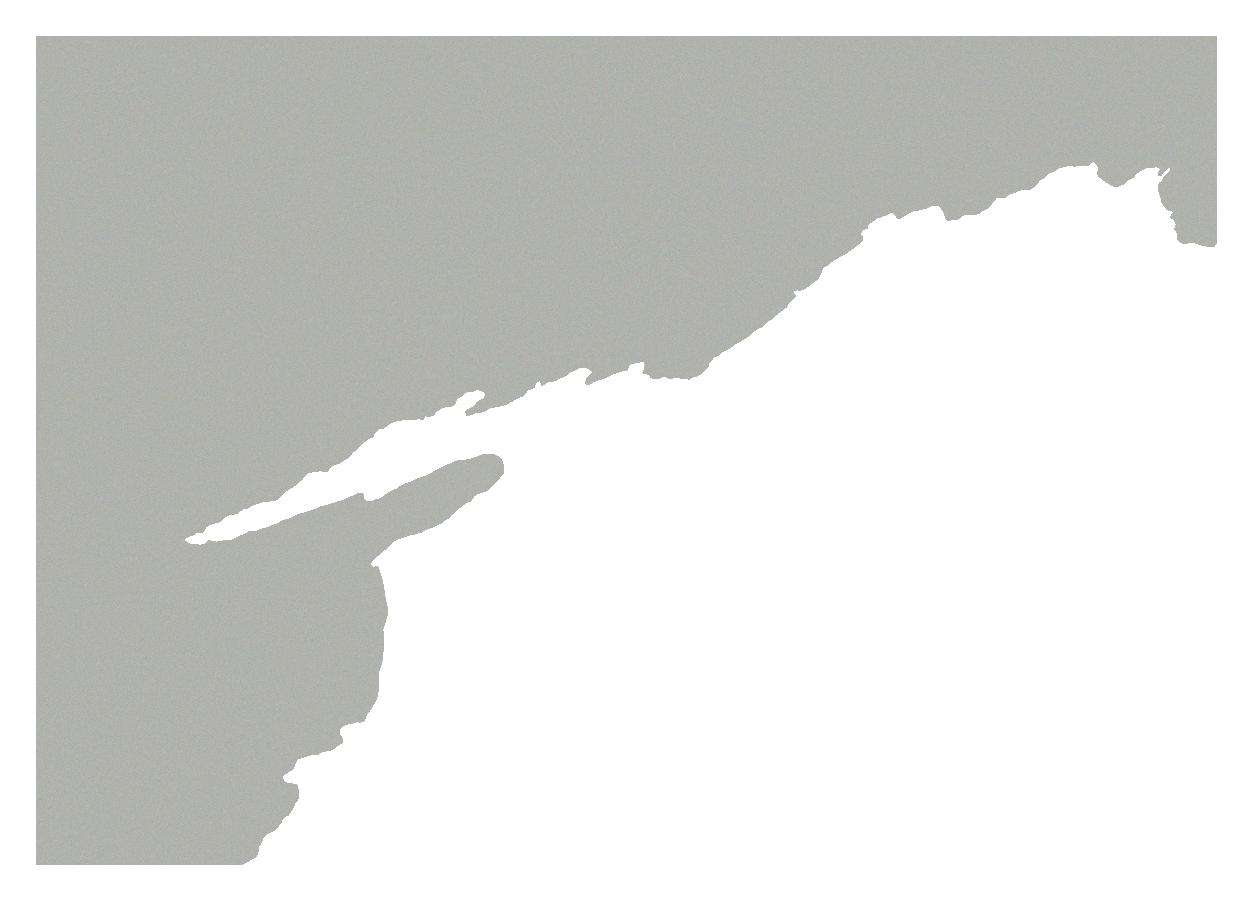

TARVA

Tarva is a group of Islands located west of Botngård. Husøya, the largest Island of the group and has 15 permanent residents, mostly farmers. Cows, sheep and reindeer are scattered within large enclosures dividing the landscape. Although there are not many permanent residents, there are a lot of vacation homes on the island, and in summer there could be more that 120 people living on the island. The military has an operating radio station along with a large shooting range on the south end of the Island. Tarva is known for being a nice spot for kayaking, and with this experiences some tourism. There is a large gathering of bird species within Tarva, and some islands are protected in different periods during the year to prevent people from disturbing the wildlife.

The Germans started the building of Tarva coastal fort in the summer of 1940. The main artillery consisted of 3 “28 cm SKL/45 sledeaffutasje” cannons with a range of 35 km, along with this “Mammut Tanne ’’ the biggest type of radio station built during the war.

9

11

Day 3

We met Svein, living by the chapel on Tarva. He told us that he was very proud of having the strongest defense line bordering his property while smiling. Multiple bunkers riddled the small hills surrounding his small farmstead. He proceeded to tell us about his own grandmothers experience of the war: When the Germans came to Norway, they occupied a large part of the island. Everybody living within the boundary of the planned coastal fort were banished. His grandmother, who had become a single-mother of three, was sent away in shock without any place to stay. Following the war and the Germans leaving, the Norwegian military expropriated the property. This meant that his grandmother who was evicted from her home had to buy back her own house and property.

Day 4

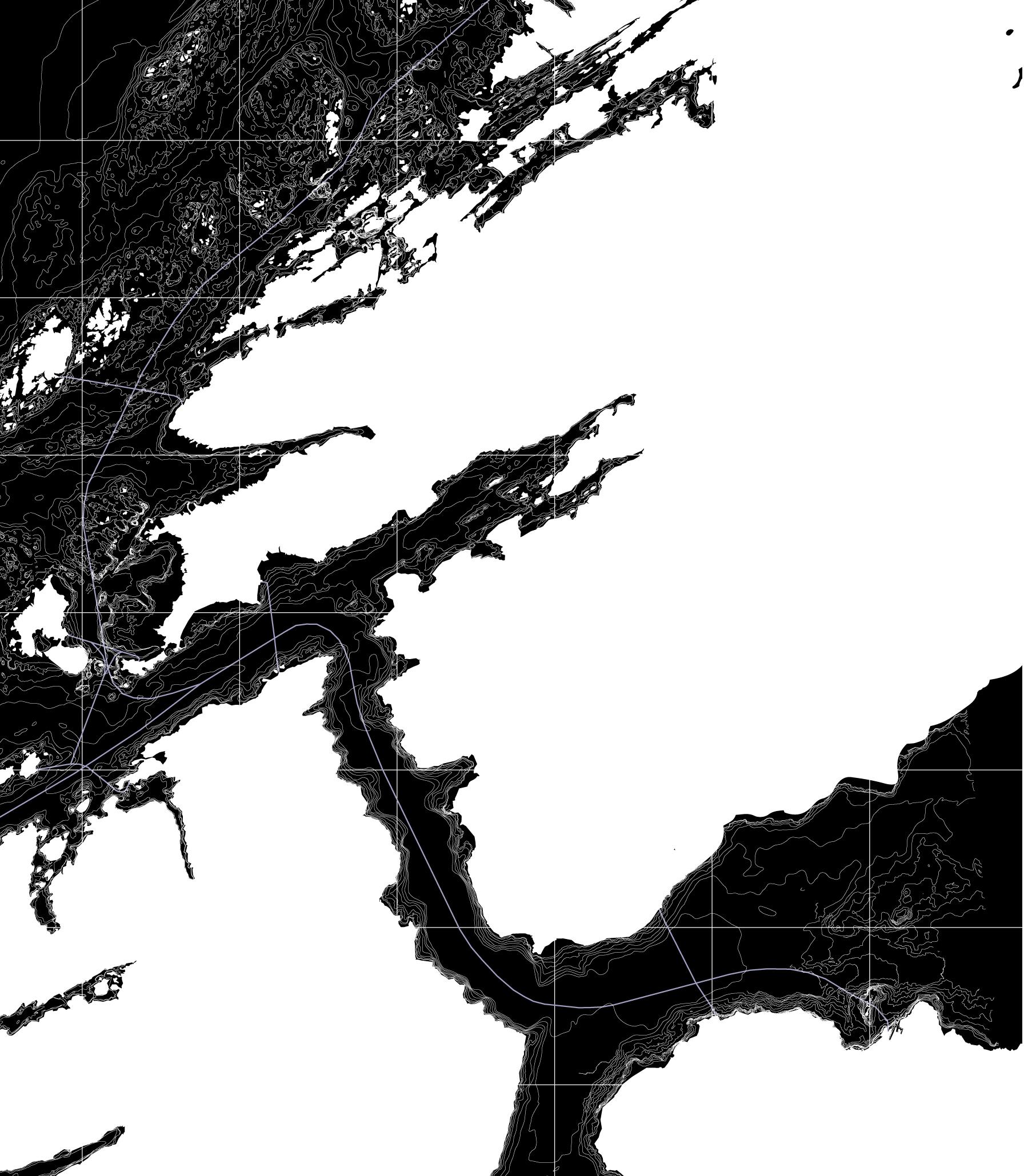

The Germans’ effort to conceal the bunker in nature made it look like the concrete belonged to the landscape. The grass covering the big volume made it even harder to distinguish the difference between structure and landscape. In a way doing what many architects believed to be the most ethical way of placing architecture into a landscape. Seamlessly fitting the architecture to the landscape. The smaller bunkers even had trees growing on top of the gray concrete as if nature had accepted the structure as part of itself.

Day 5

After talking to Viggo on the ferry, it appears that the island is divided into two parts, the part facing towards the mainland, and the one facing the ocean (the right side). Apparently, there are a lot of people that owns cabins on the island, with only a few farmer living there permanently. One farmer in particular own most of the Island, while Paul, that we have been in contact with owns the northern part which encloses most of the bunkers. This was the zone which were annexed by the Germans and where they housed 2000 soldiers along with 500 prisoners of war, mostly Slavic soldiers. The Germans usually build “soldatenheim” in connection with they’re bigger outposts, a place where the soldiers could watch cinema, eat, and relax. The prisoners from the Soviet Union and other Slavic nations where the primary workforce utilized by the Germans for the construction of the Northern part of the Atlantic Wall. Extract from travel-journal

12

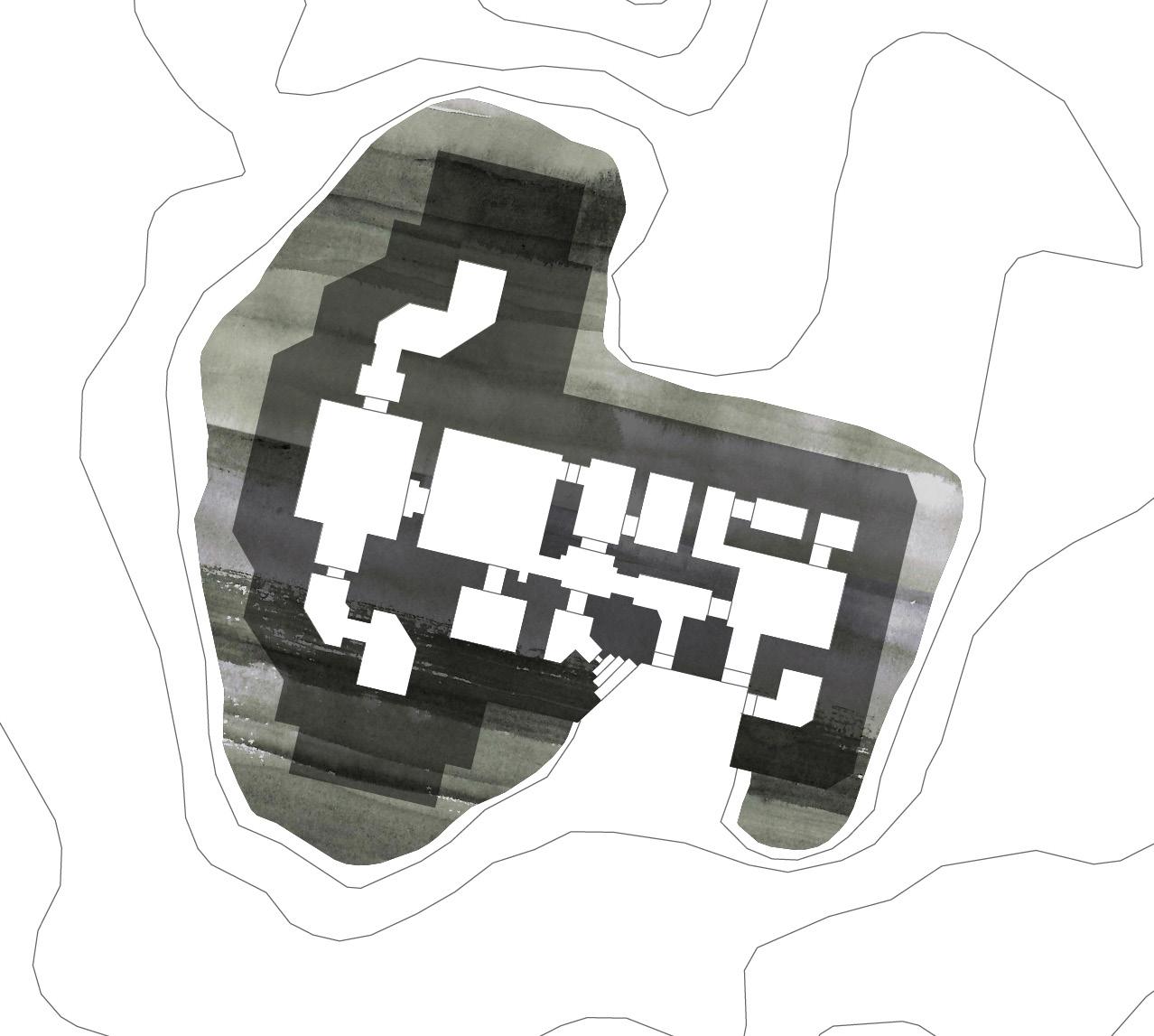

13 101 102 104 106 107

14 M: 1:5000 103 105

STRUCTURE 101 (+102)

SCALE: XS

LOCATION: 63.825629, 9.413612

FUNCTION: OBSERVATION POST

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

15

16

Section + plan: M: 1:200

STRUCTURE 103

SCALE: S

LOCATION: 63.817333, 9.431346

FUNCTION: BARRACK

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

17

Section + plan: M: 1:200

STRUCTURE 104

SCALE: S

LOCATION: 63.826038, 9.415308

FUNCTION: ANTI-AIRCRAFT GUN

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

19

Section + plan: M: 1:200

STRUCTURE 105

SCALE: M

LOCATION: 63.820986, 9.435070

FUNCTION: BARRACK

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

21

STRUCTURE 106

SCALE: L

LOCATION: 63.824987, 9.414950

FUNCTION: COMMANDO BUNKER

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

23

Section + plan: M: 1:200

STRUCTURE 107 - ”MAMMUTEN”

SCALE: XL

LOCATION: 63.662944, 8.310448

FUNCTION: RADIO STATION

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET

COASTAL FORT: 306/III HUSÖEN

25

Section + plan: M: 1:200

27

WOUNDED LANDSCAPE

The construction of the bunkers has drastically altered the landscape. Large masses of soil and rock have had to give way to the construction of the bunkers - facilities that are located wholly or partially underground. These structures are the result of permanent landscape interventions and tell us about our involvement with the earth. The structures have been situated in these landscapes for almost 80 years, and have gradually become a part of the landscape. Walking in these landscapes gives us the feeling of being in contact with history.

“Sometimes the landscape suffers from having us live and work in it. Nonetheless, for better or for worse, it is there that the history of our involvement with the earth is stored”

Peter Zumthor

Peter Zumthor

28

STORFOSNA

Storfosna is an island west of Brekstad. The island is presumed to have been a place of power centered around Storfosna Gods dating back to the 12th century. Today there are 139 people living on the island, and a lot of people come here to enjoy deep sea fishing.

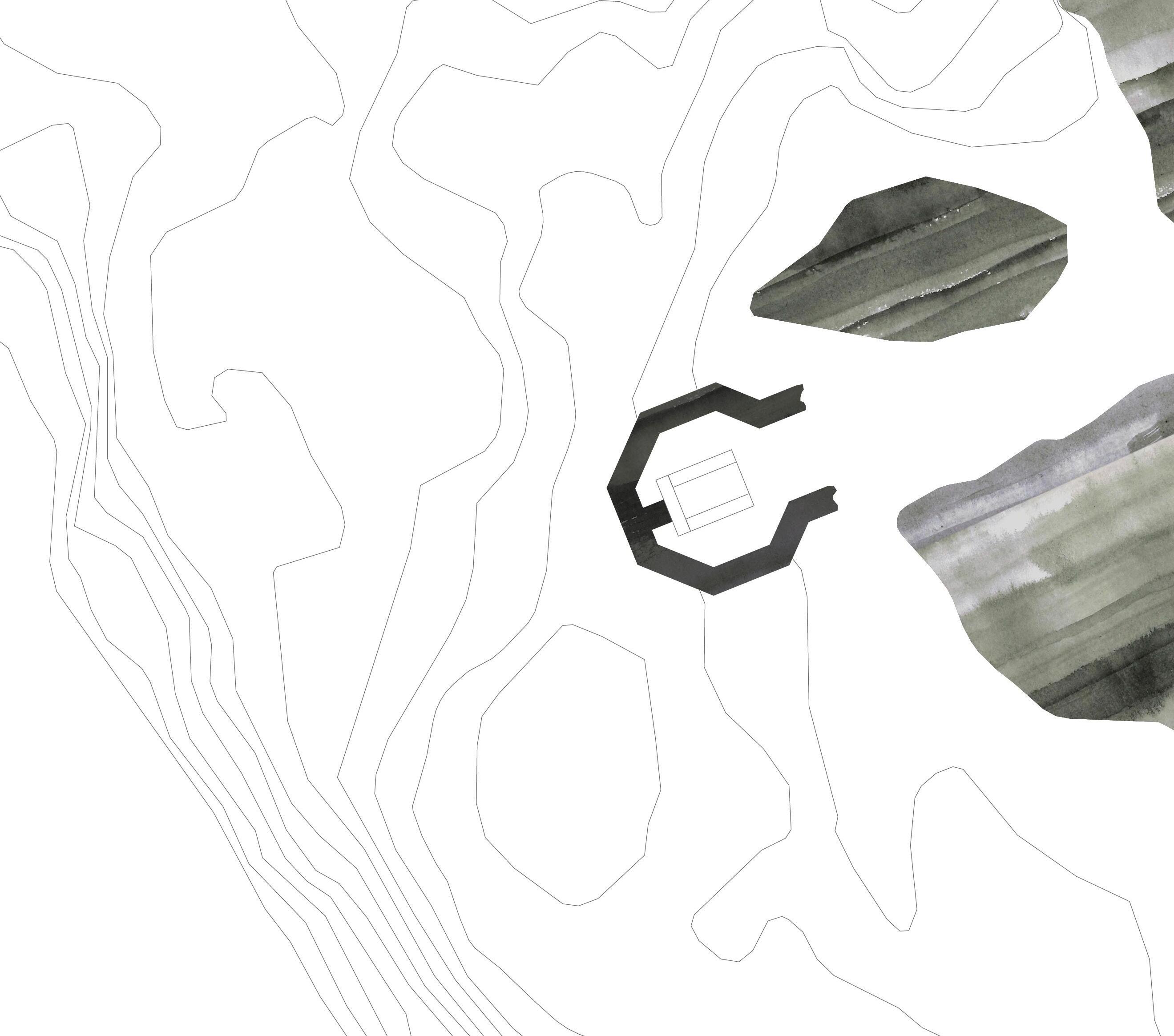

In the summer of 1942 the Germans established the coastal fort on Storfosna. It was equipped with 6 “15 cm K403” cannons with a range of 23 km. The fort was built on top of a rocky ridgeline on the south-western part of the island. Anti-aircraft guns, and close defense positions placed scattered on the ridge protected the cannons. The whole fort was connected by a system of tunnels linking the radio stations and command bunker to the guns.

29

31

Day 7

The fort built by the Germans was centered along a rocky ridgeline on the south-western part of the island. They built anti-aircraft guns on the top of the ridge, connecting them with a huge system of tunnels. After the war the Norwegian army reused this fort as a radar station, to help pinpoint targets for a huge cannon constructed at Kråkvåg in the 90-ties. To our great disappointment a lot of the structures here were either blocked off or demolished by the Norwegian army in 2007, some years after they stopped using the

Extract from travel-journal

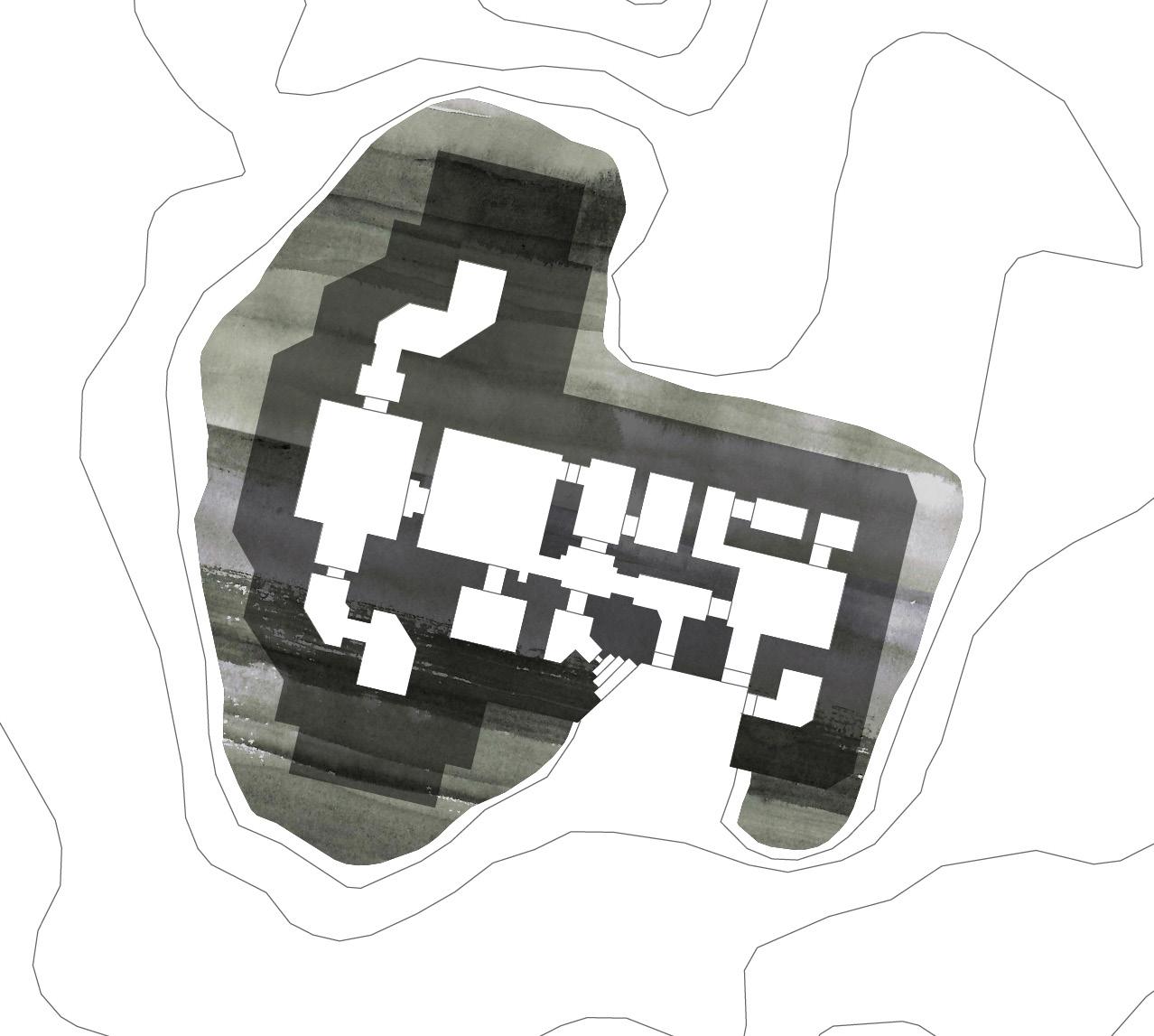

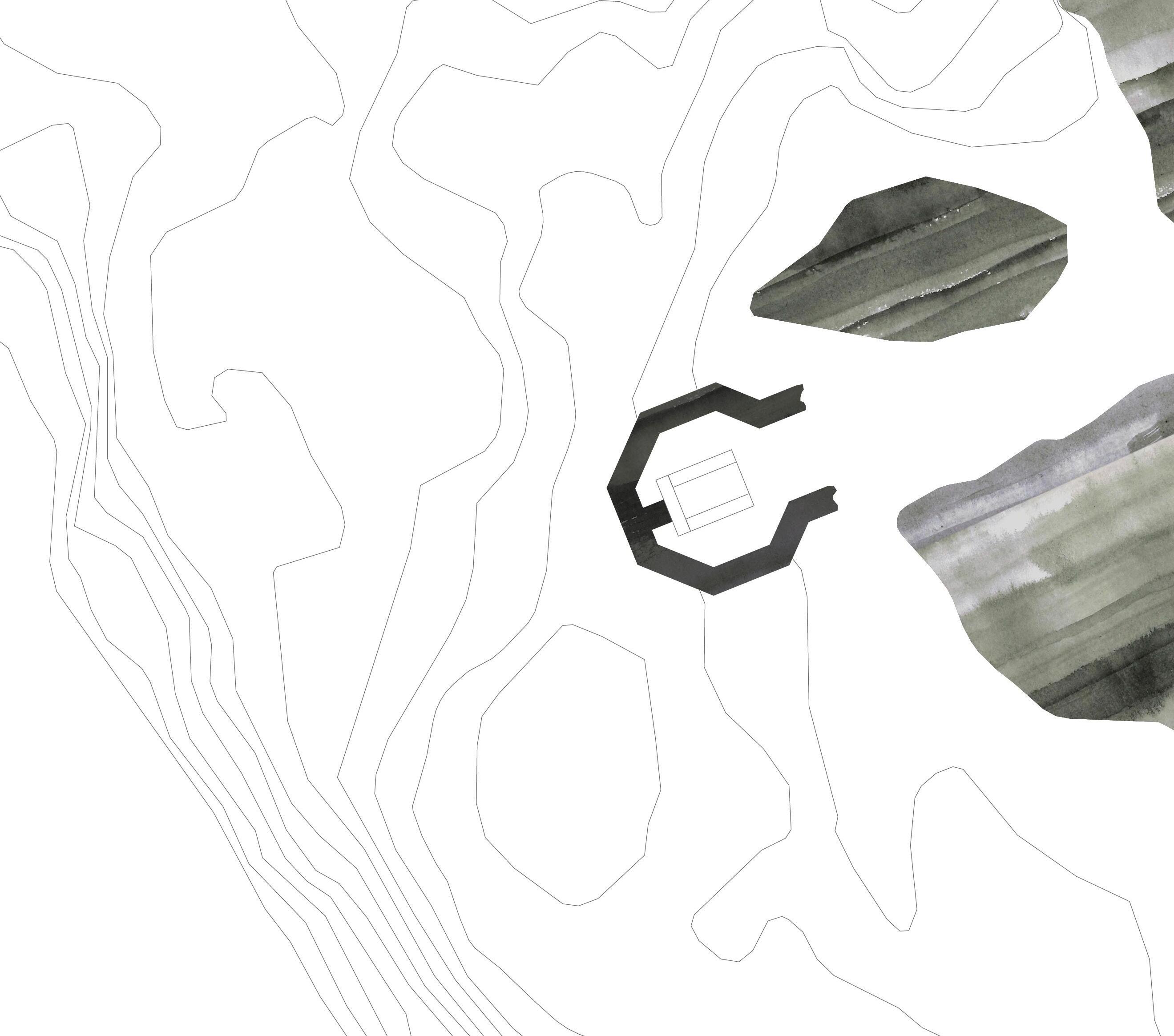

108

M: 1:2500

STRUCTURE 108

SCALE: M

LOCATION: 63.662944, 8.310448

FUNCTION: BARRACK

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE ÖRLANDET 506

COASTAL FORT: 72/975 STORFOSEN

35

Section + plan: M: 1:200

37

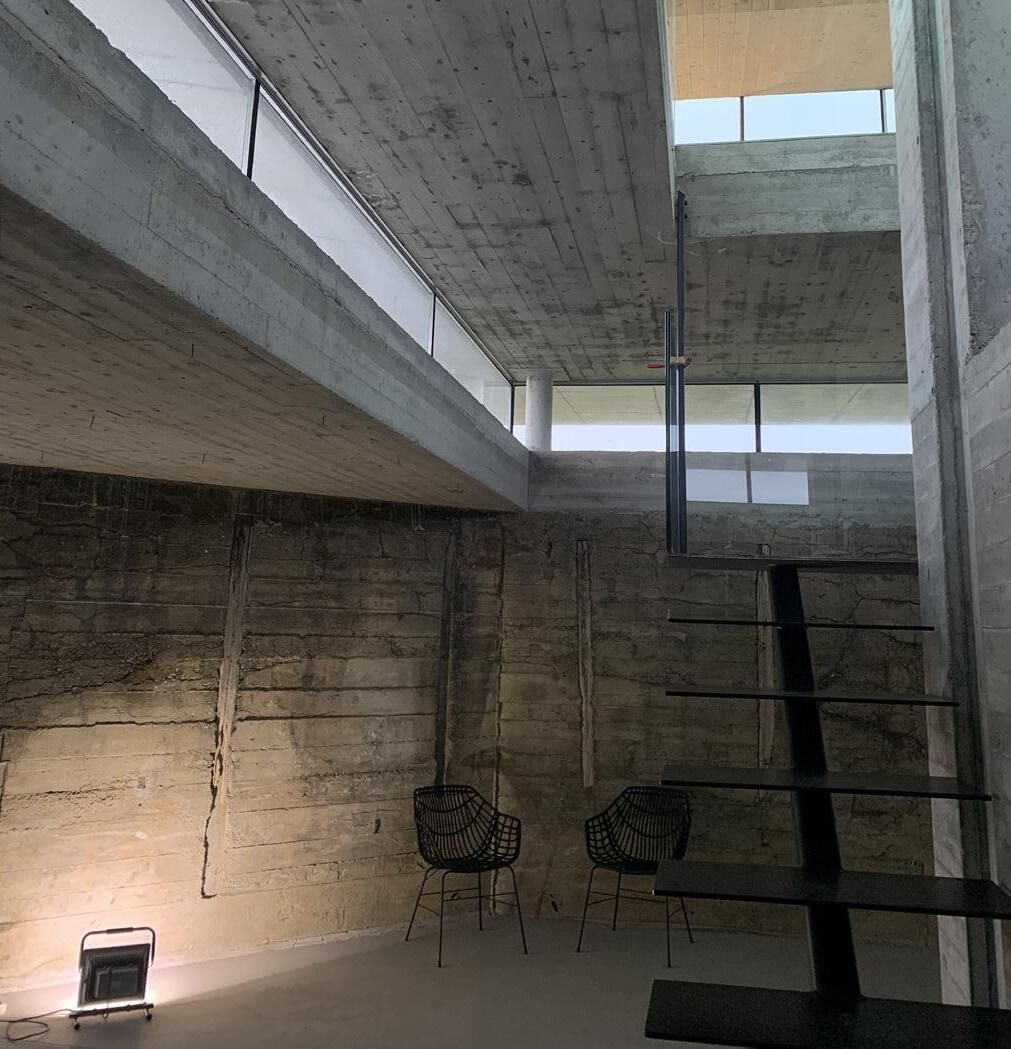

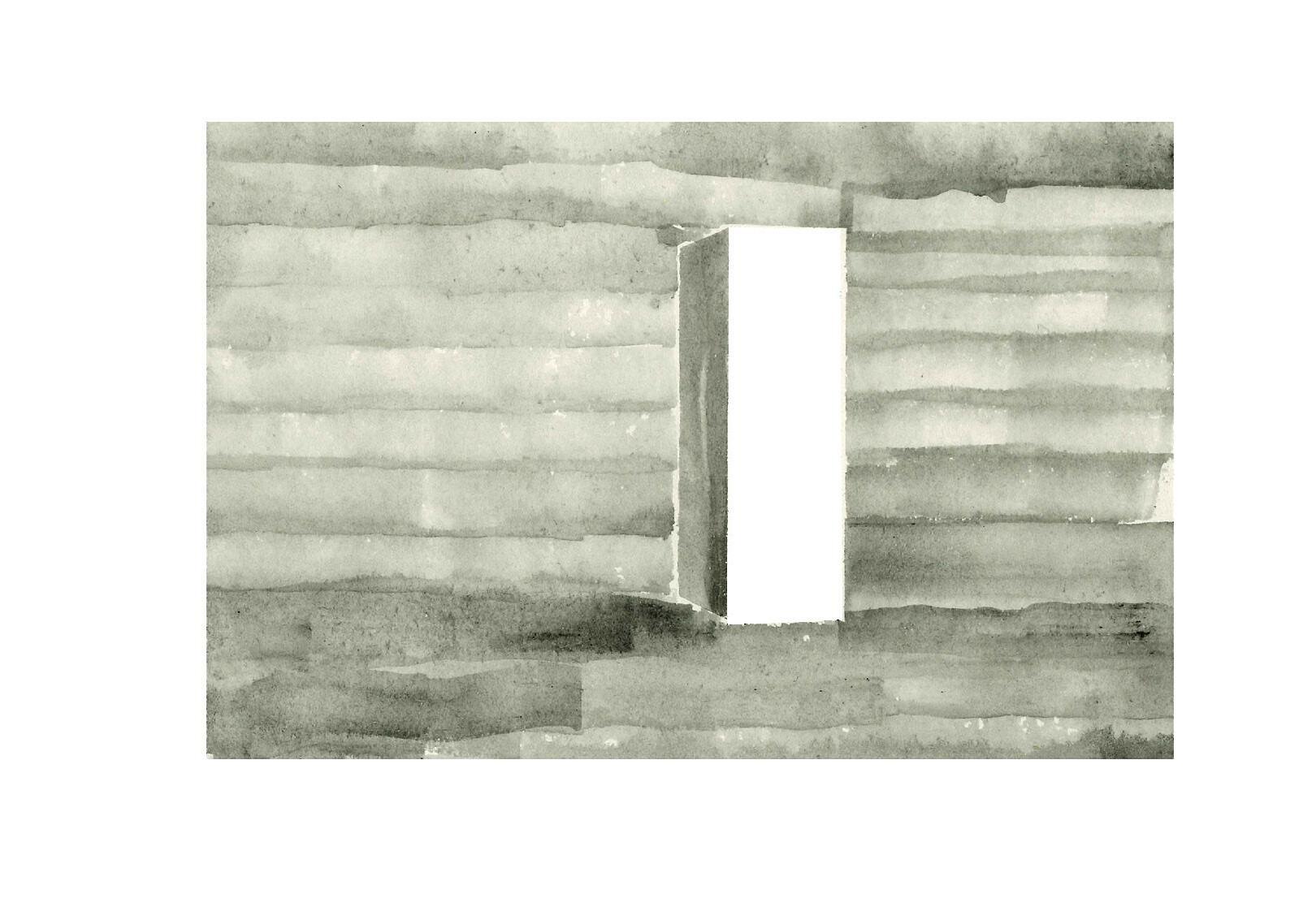

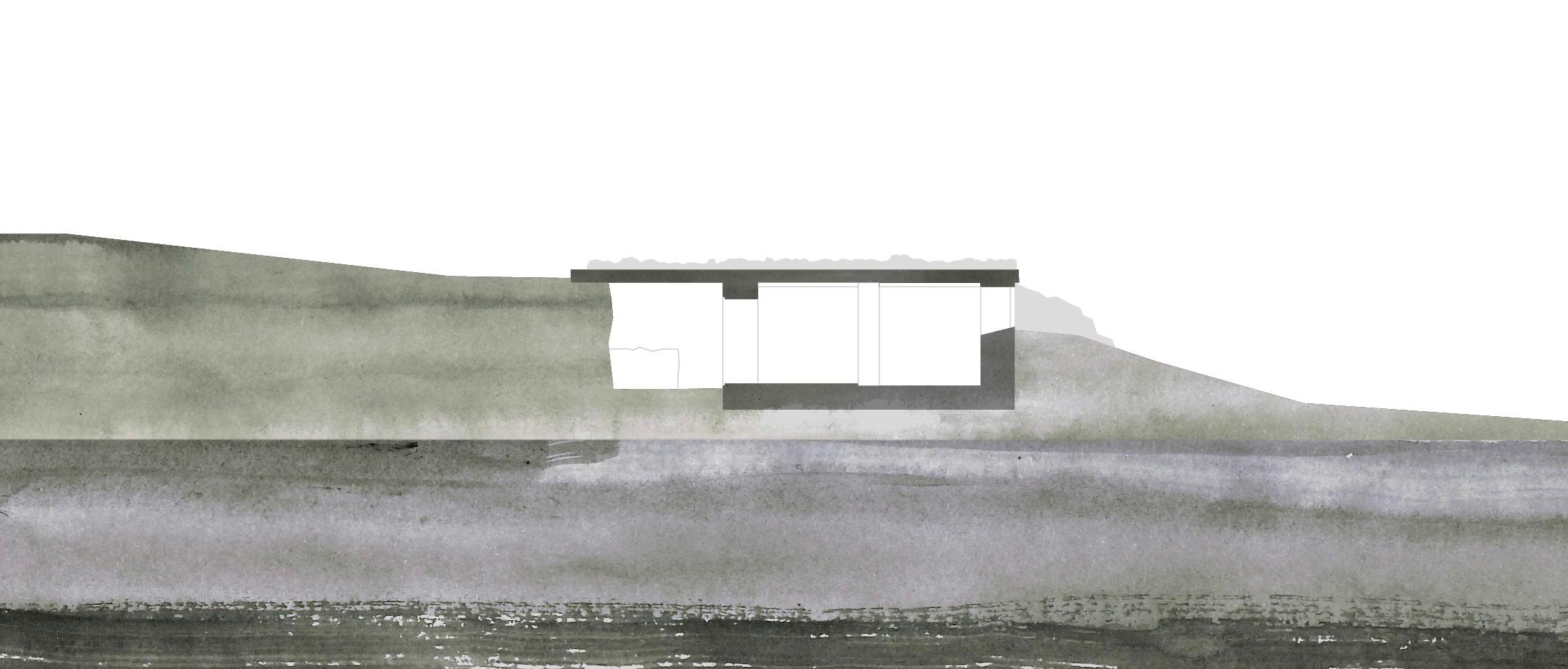

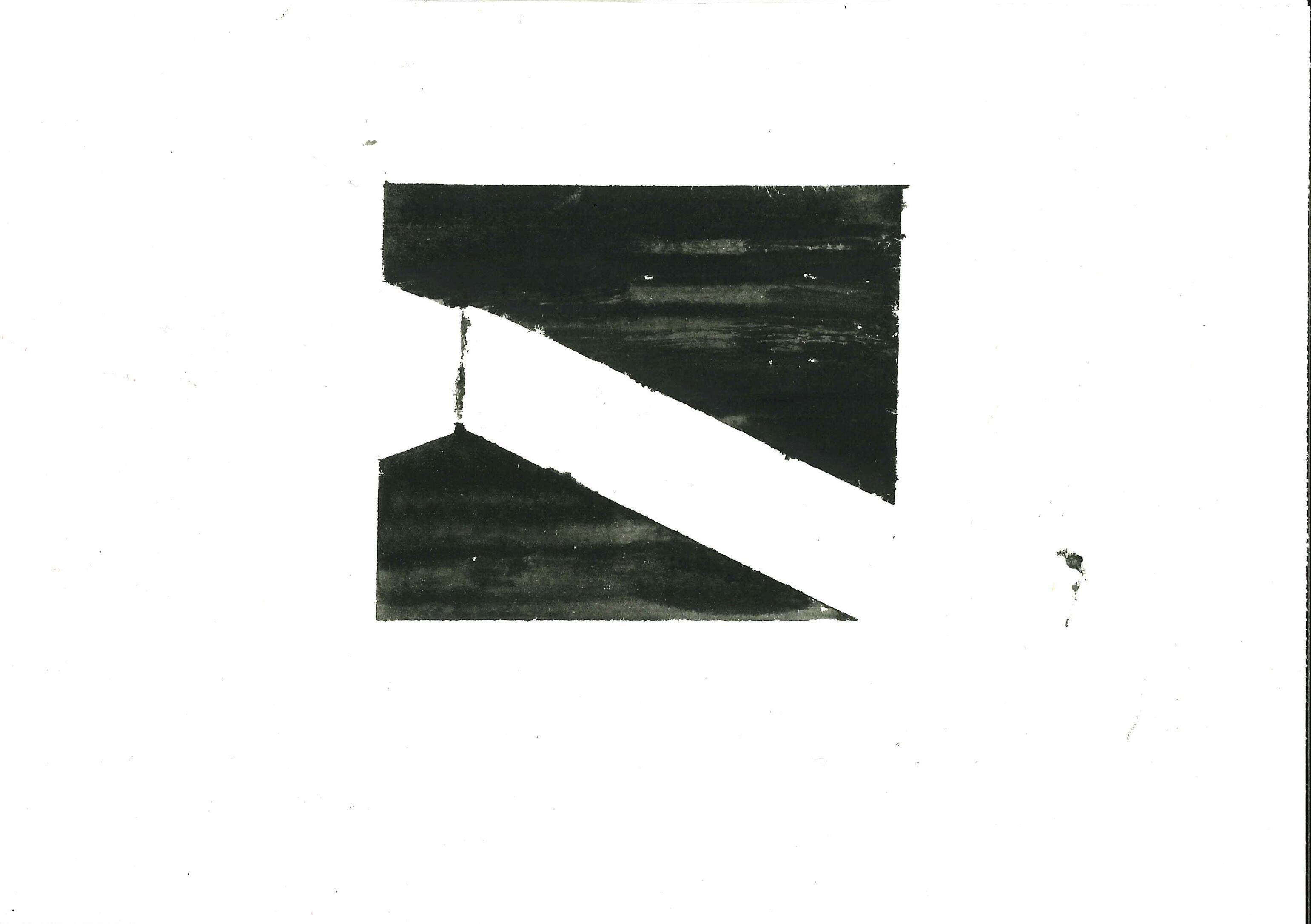

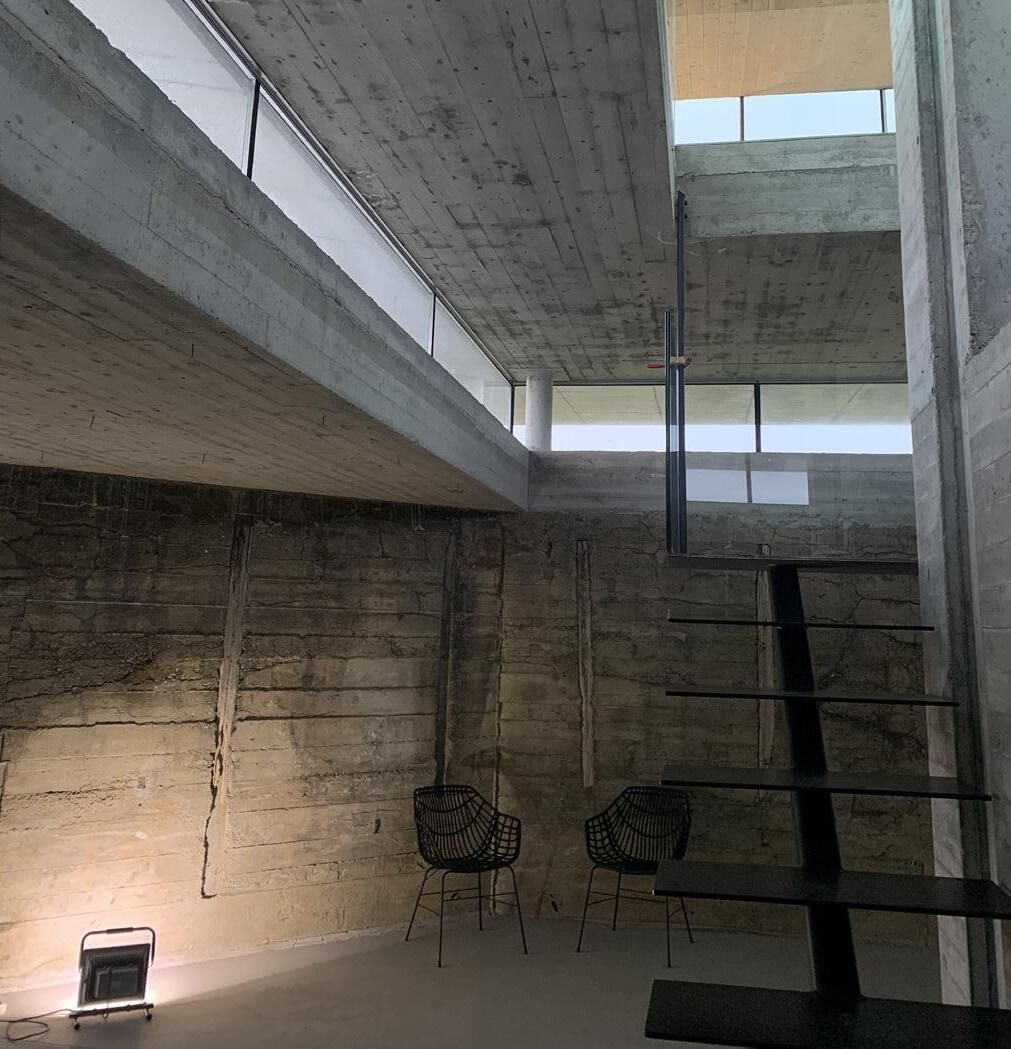

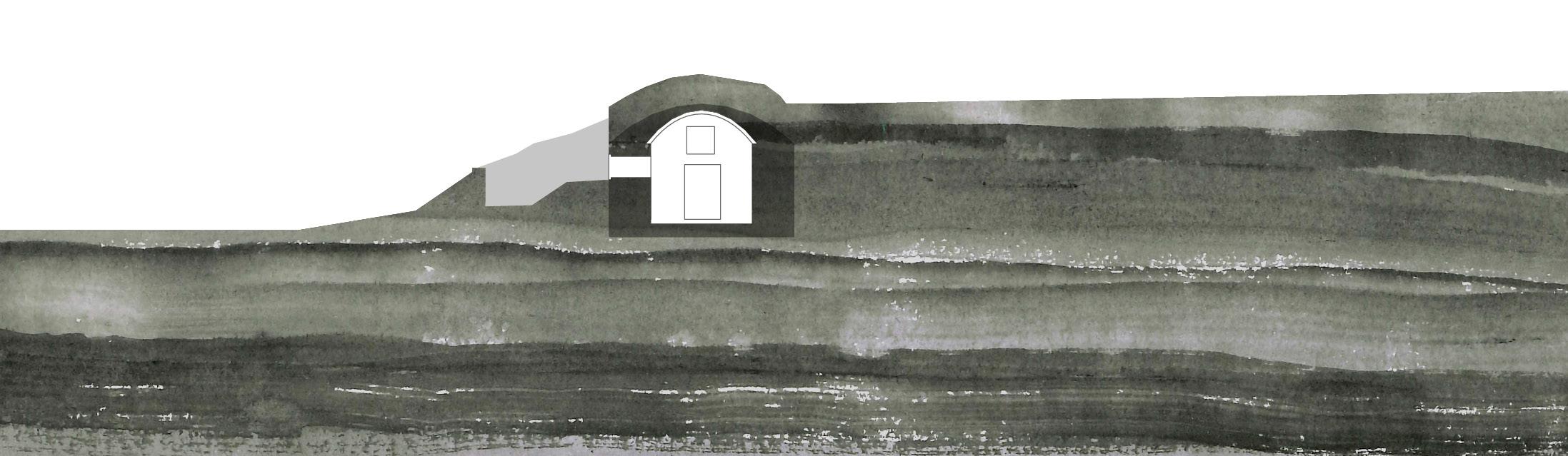

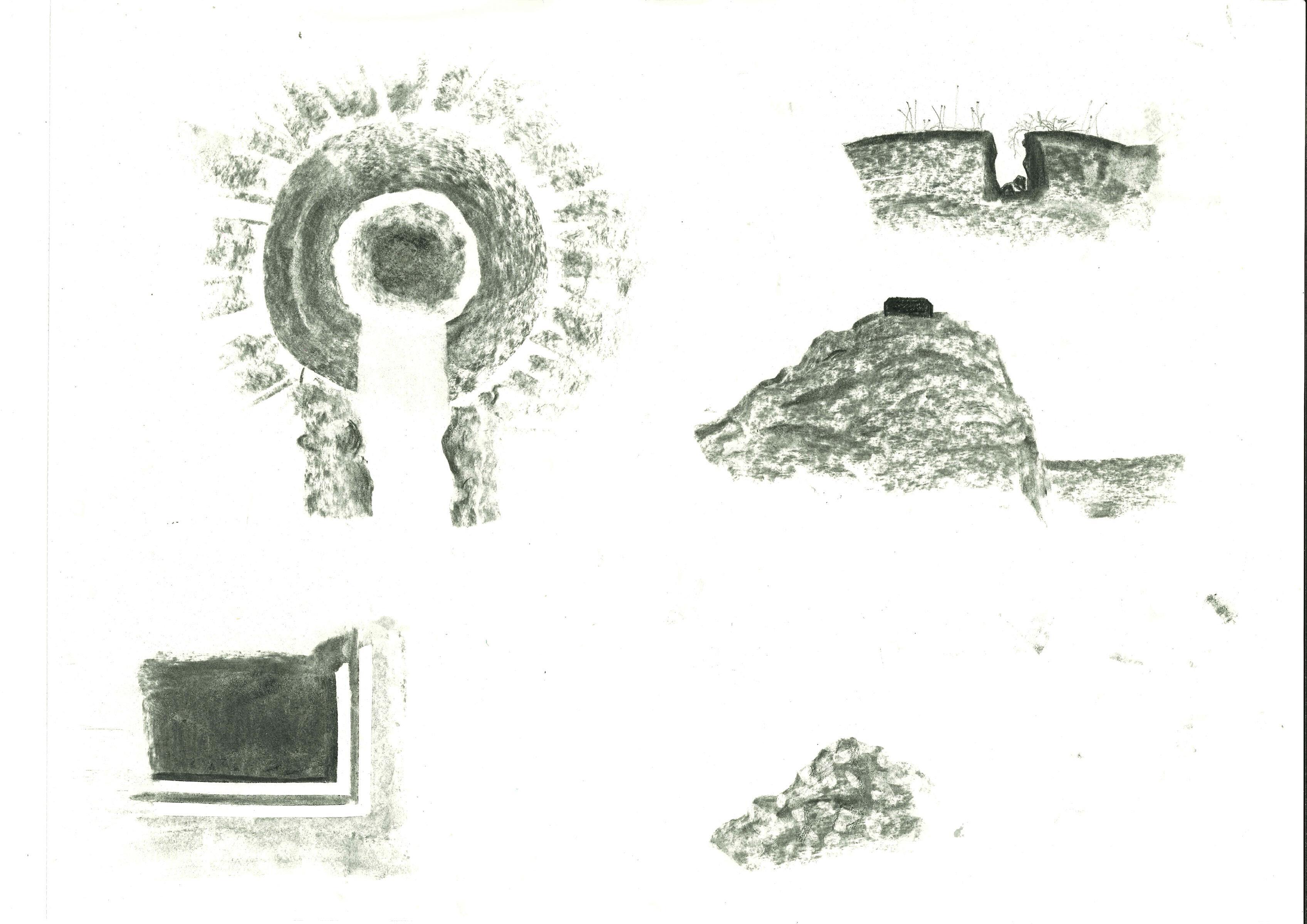

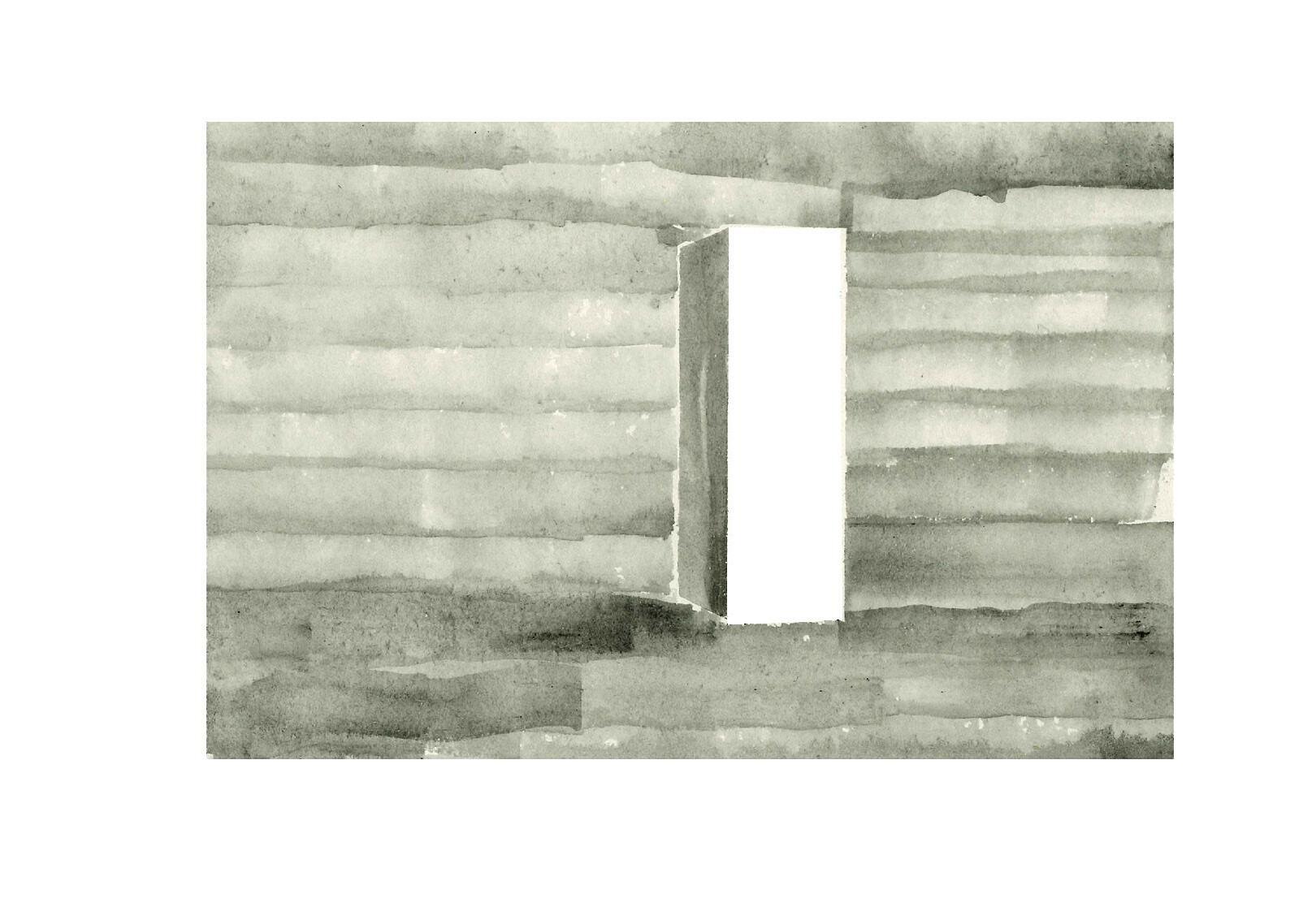

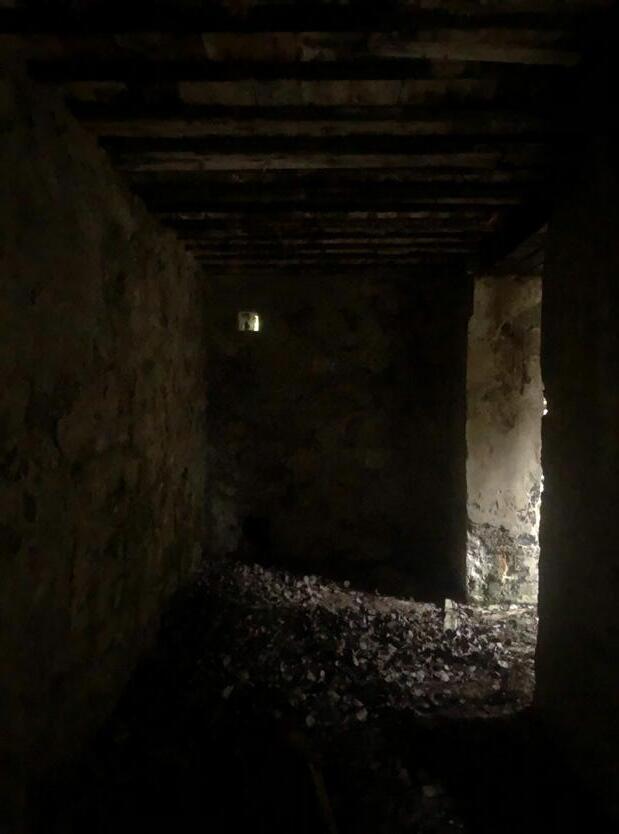

PLAY OF SHADOWS

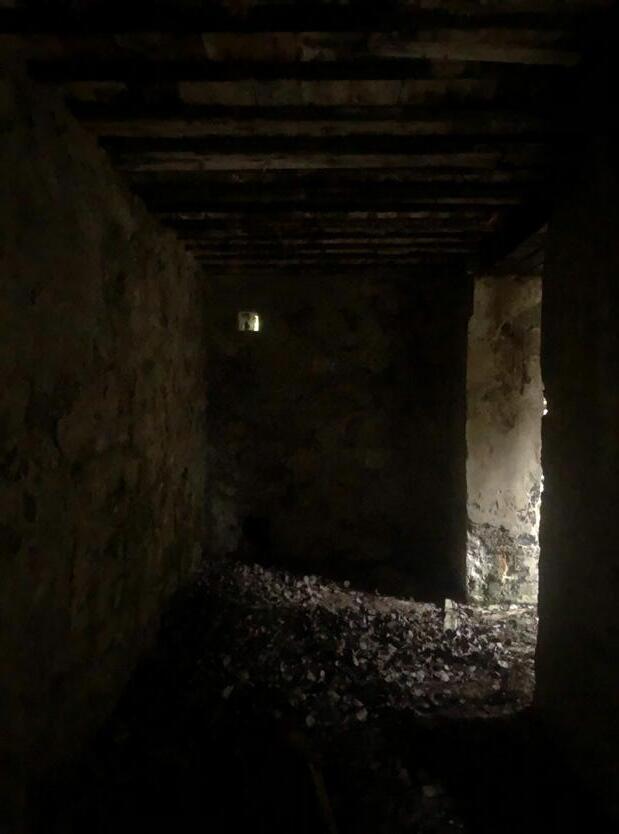

Experiencing a bunker is about sensing transitions. Transitions between up and down, between outside and inside, between light and shadow. Sounds are muffled, smells change and you lose direct contact with the weather and wind. Most dramatic is the visual impression; a bunker can appear as a mysterious object as you glimpse it from a distance. As you get closer, and then step down into it, the space or spaces reveal themselves. You enter an underworld, sheltered from the weather. An underworld consisting of solid concrete and precise, geometric shapes. The light that is led down from the outside, which gradually surrenders to darkness. Darkness is the absence of light, but what does this mean?

In the book “In Praise of Shadows” (2001), author Junichiro Tanizaki writes about the West’s neglect of the quality of darkness. The interaction between light and darkness is what makes spaces truly interesting. Light tells us something about what is happening on the surface. But what is happening on the surface is not the only interesting thing. And darkness does not only represent the absence of light. Darkness brings out the mystery in a bunker. The dark corners of these precise constructions give the space a tension. A tension between light and darkness. And where does the mystery go if everything is illuminated?

38

HEMNSKJELA

Hemnskjela is an island located in Hitra Kommune, along the county road dubbed “The salmon road” leading to the Islands Hitra and Frøya. The 79 people living on the island can easily commute to the mainland by bridge and a tunnel to Hitra.

The Germans decided to create a coastal fort on the Northern part of Hemnskjela, in May 1941. 700 Germans along with 100 POW came to the small island and started building fortifications. The main artillery consisted of 6 “21 cm Mrs” cannons with a range of 10 km and 4 “15,5 cm K416” with a range of 15 km. These cannons were supported by 10 smaller connons. The main artillery were protected by multiple close defense positions with machine guns, flamethrowers and minefields.

39

41

Day 9

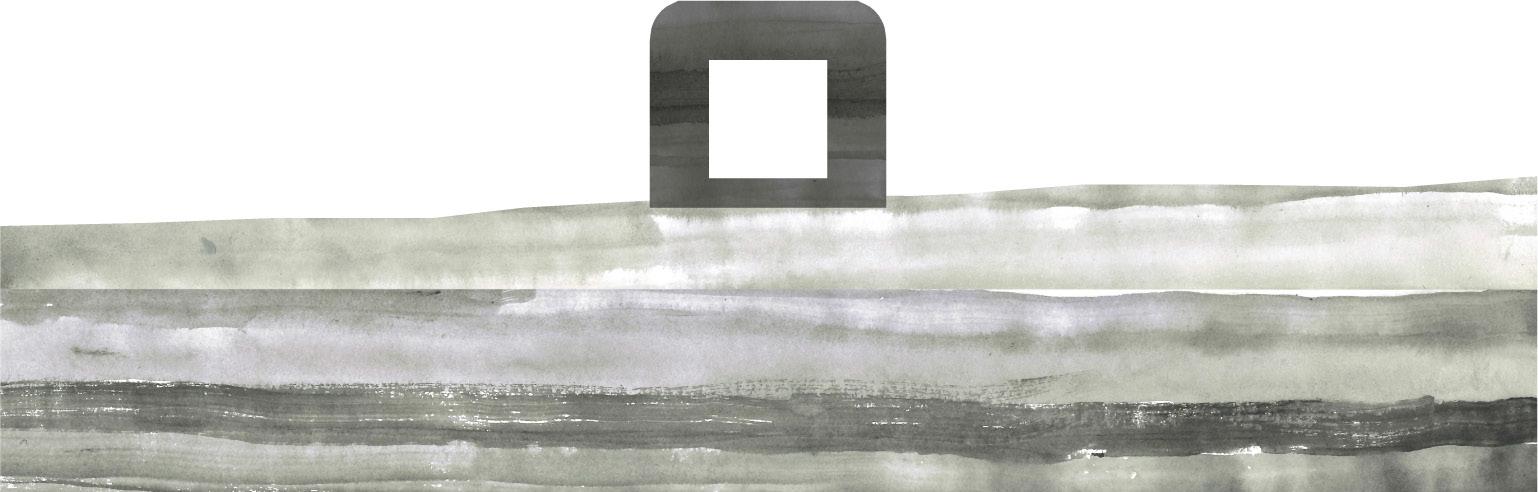

We decided to make another stop on our way to Titran. We arrived in a residential area in Hemnskjela, and right there; on the outer part of the residential area we found the bunker we had spotted on the map. It was striking to see the bunkers’ proximity to the residential area; we were now used to seeing the fortifications standing by themselves in the landscape. We investigated multiple artillery cannon positions carved into the landscape, but there was one of the more “bunker shaped” bunkers that caught our attention, with a curved shape peeking up from the terrain with small horizontal slits, only hinting at the size of the bunkers interior.

Extract from travel-journal

42

109

M: 1:2500 109

STRUCTURE 109

SCALE: M

LOCATION: 63.497855, 9.109652

FUNCTION: COMMANDO BUNKER

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE DRONTHEIM WEST

COASTAL FORT: 21/975 HEVNSKJÖL - NORD

Section + plan: M: 1:200

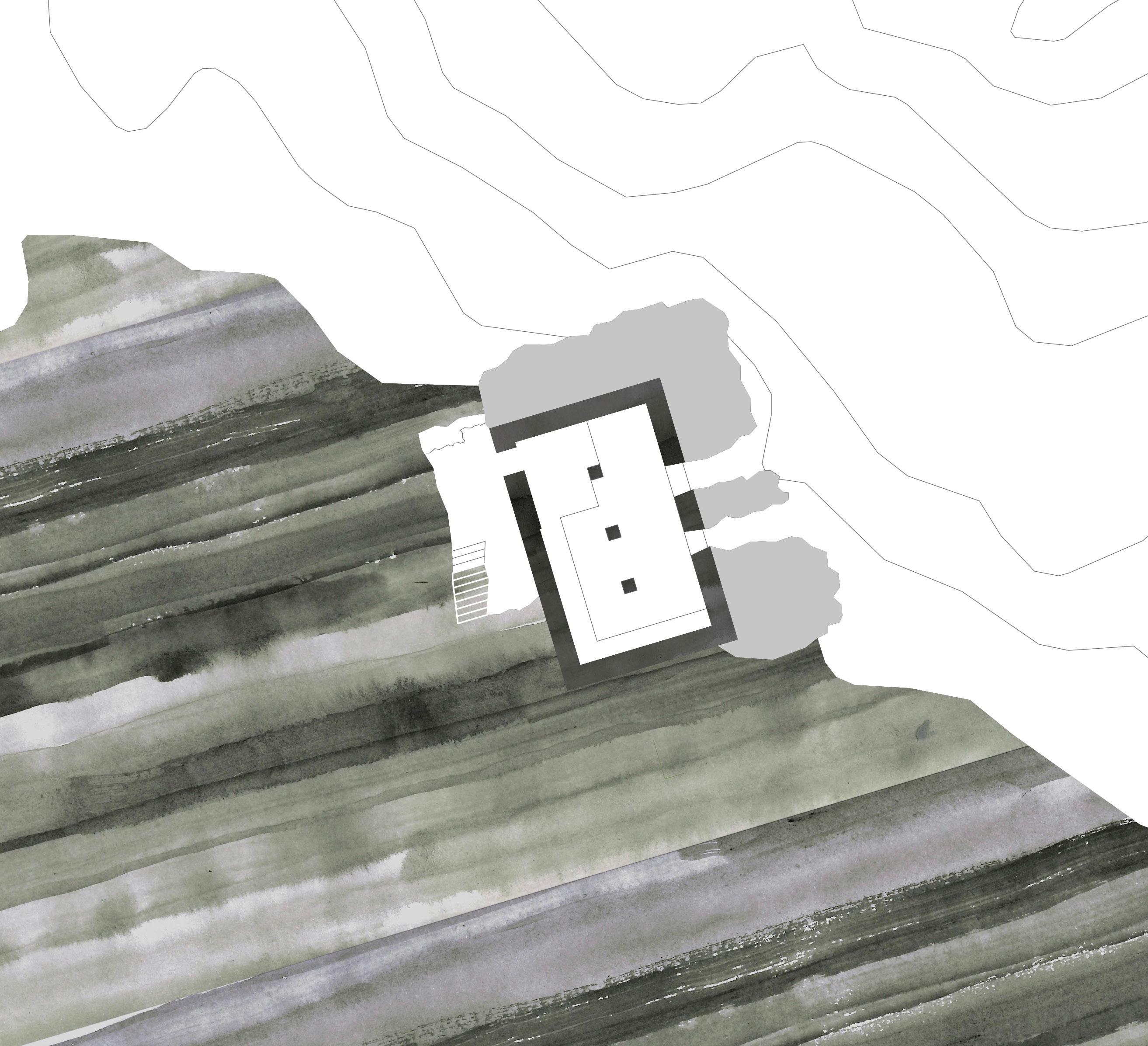

FRØYA

Frøya is an Island north of Hitra. The island has a population of around 5200 people. Throughout history Frøya has been a safe haven for fishermen. Most people still live of the fish, but not to the same extent as in the past. The old tradition is clearly present in the fishing village of Titran with around 80 residents located on the western most point of the island. Titran is known for its harsh weather, but beautiful summers, and experiences a lot of tourism.

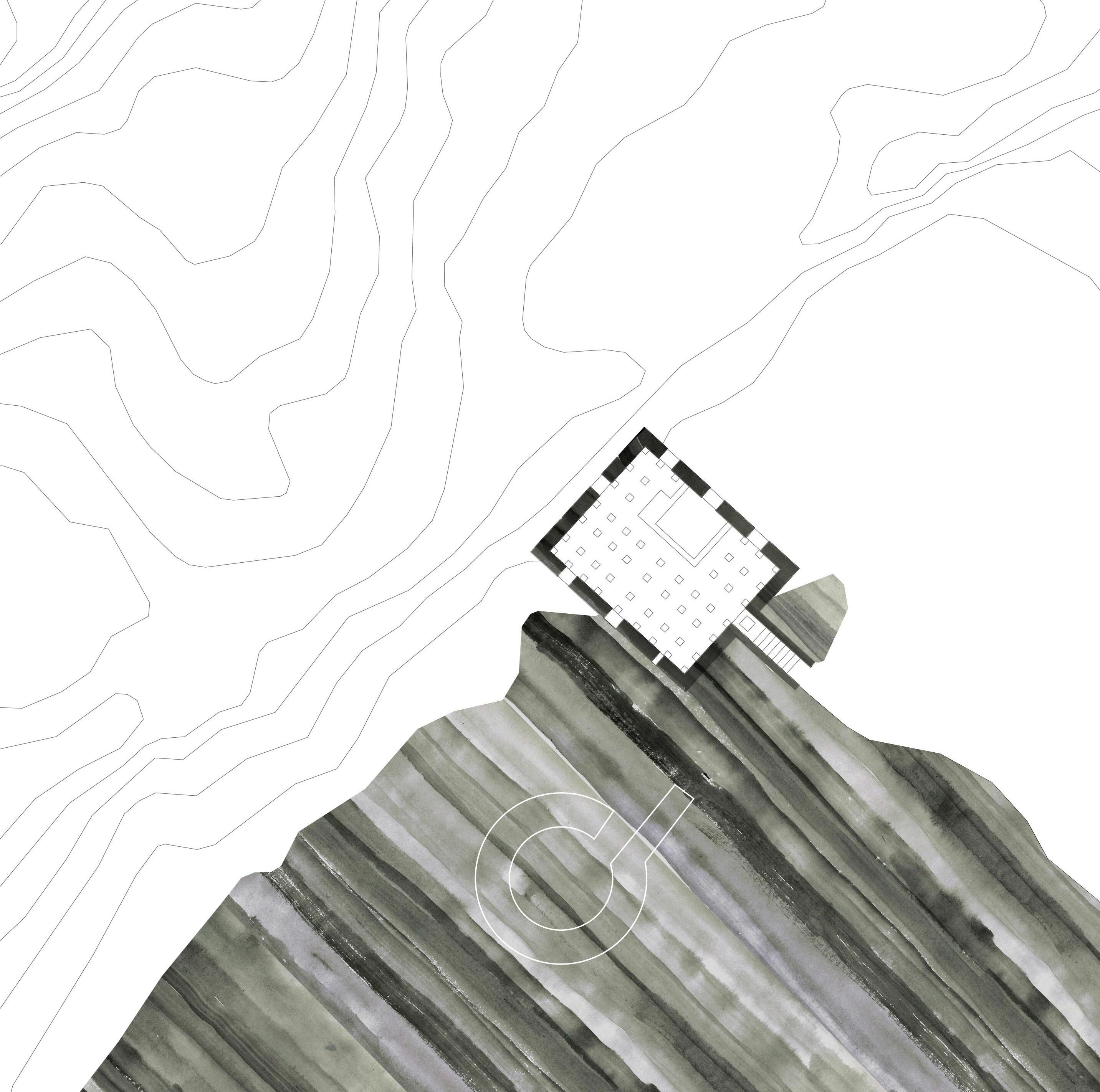

Just south of Titran lies the small islet of Stabben. The Germans started construction on the coastal fort on Stabben in May of 1941. They took over all the 14 houses situated on Stabben, the population of around 600 people in Titran doubled as the Germans occupied the small village. The fort was equipped with 4 “15 cm K16” cannons with a range of 22 km. The artillery was only used once during the war when the Germans shot one of their own ships, because they failed to identify themselves properly. The Germans planned to construct an u boat base on Frøya, but the construction never started.

47

49

Day 10

Today was a special day, we were invited to dinner by Jan, a very generous retired teacher. He made a killer Bacalao, and we got to talk to him about growing up in Titran. He made a rough estimate of a 100 people still living in Titran, but we assume that he also counted the different vacation homes. He sounded disappointed when he said that there was not much left to do in Titran. The general store had closed down, and the Cafe was only open during the summer. However earlier that day we talked to Grete, the leader of the “grendelagsforening”, she told us about a tradition they had every last weekend of the month they would gather and walk together and end up at Stabben Fort were they served coffee.

Extract from travel-journal

Extract from travel-journal

110

M: 1:2500

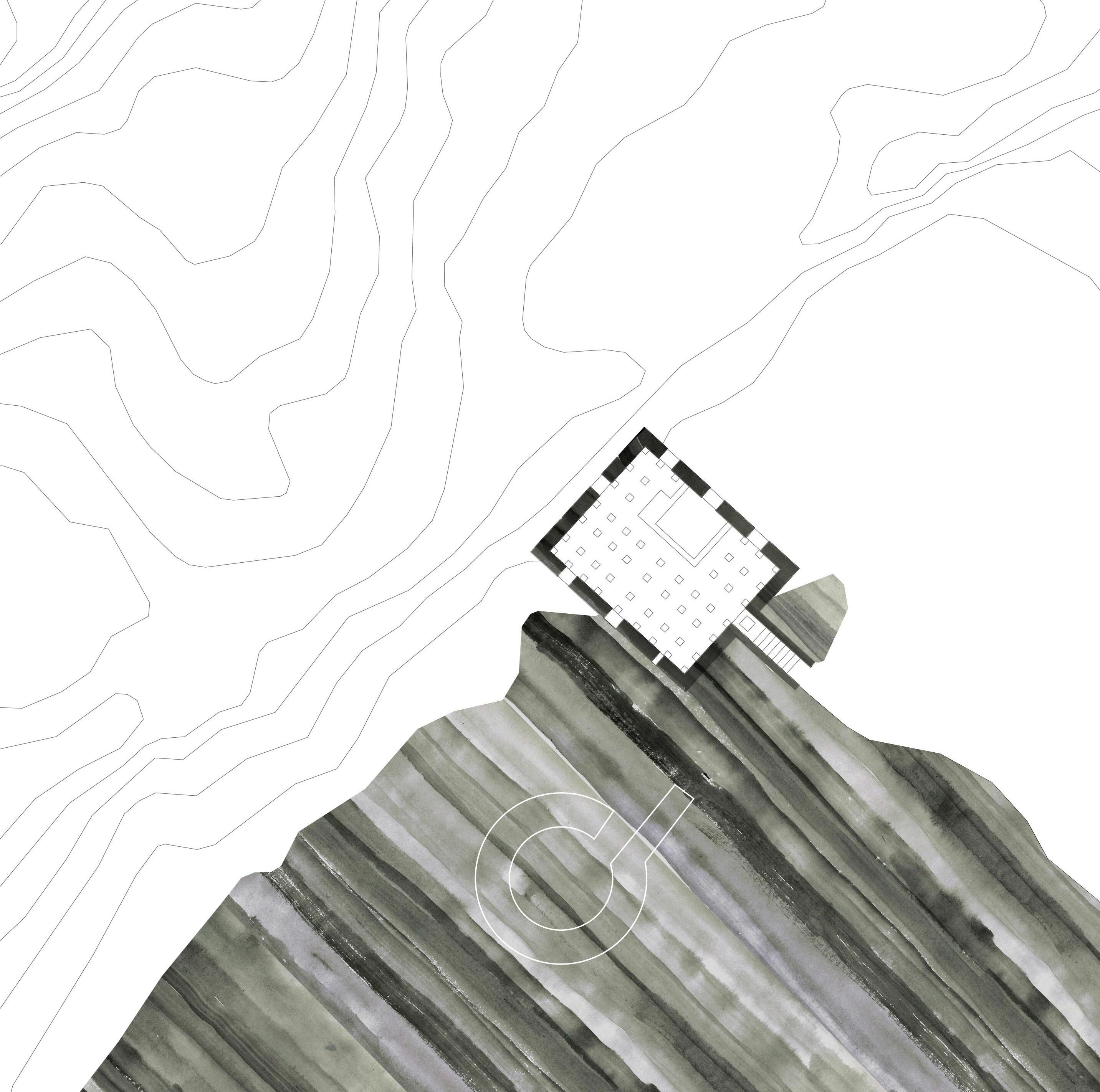

STRUCTURE 110

SCALE: XL

LOCATION: 63.662944, 8.310448

FUNCTION: NAVAL ARTILLERY CANNON

ORGANISATION: ARTILLERIE GRUPPE DRONTHEIM WEST

COASTAL FORT: 22/975 TITRAN

53

Section + plan: M: 1:200

55

56

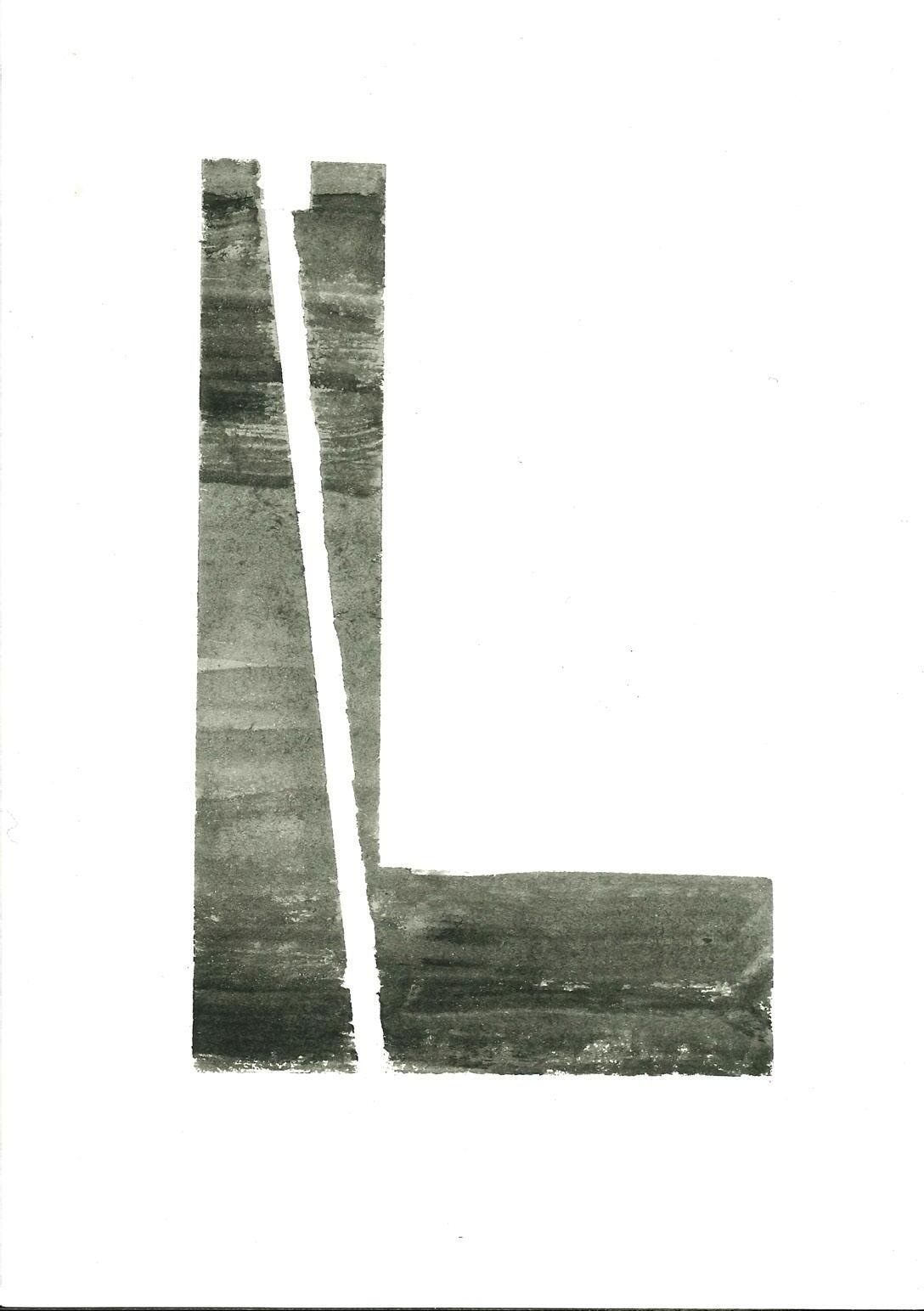

MASS AND SPACE: Collage of all bunkers measured during the trip

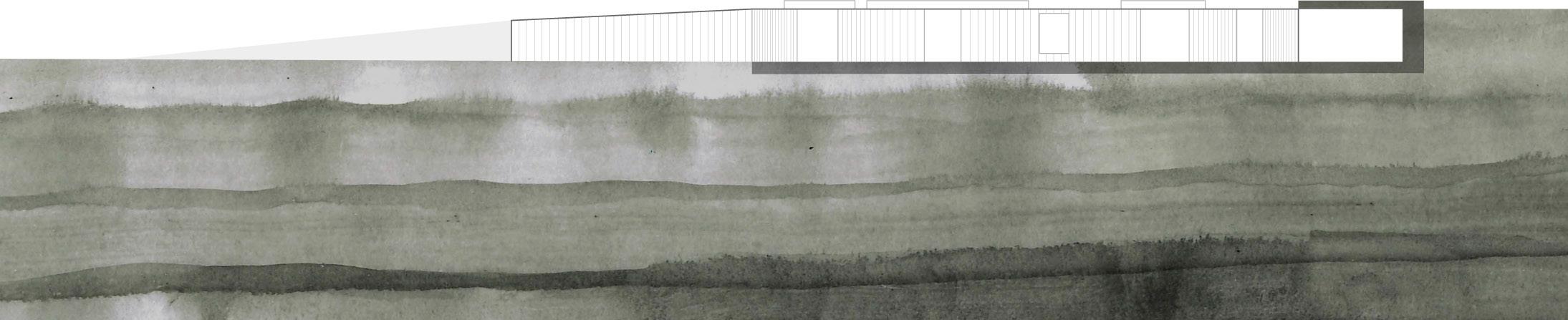

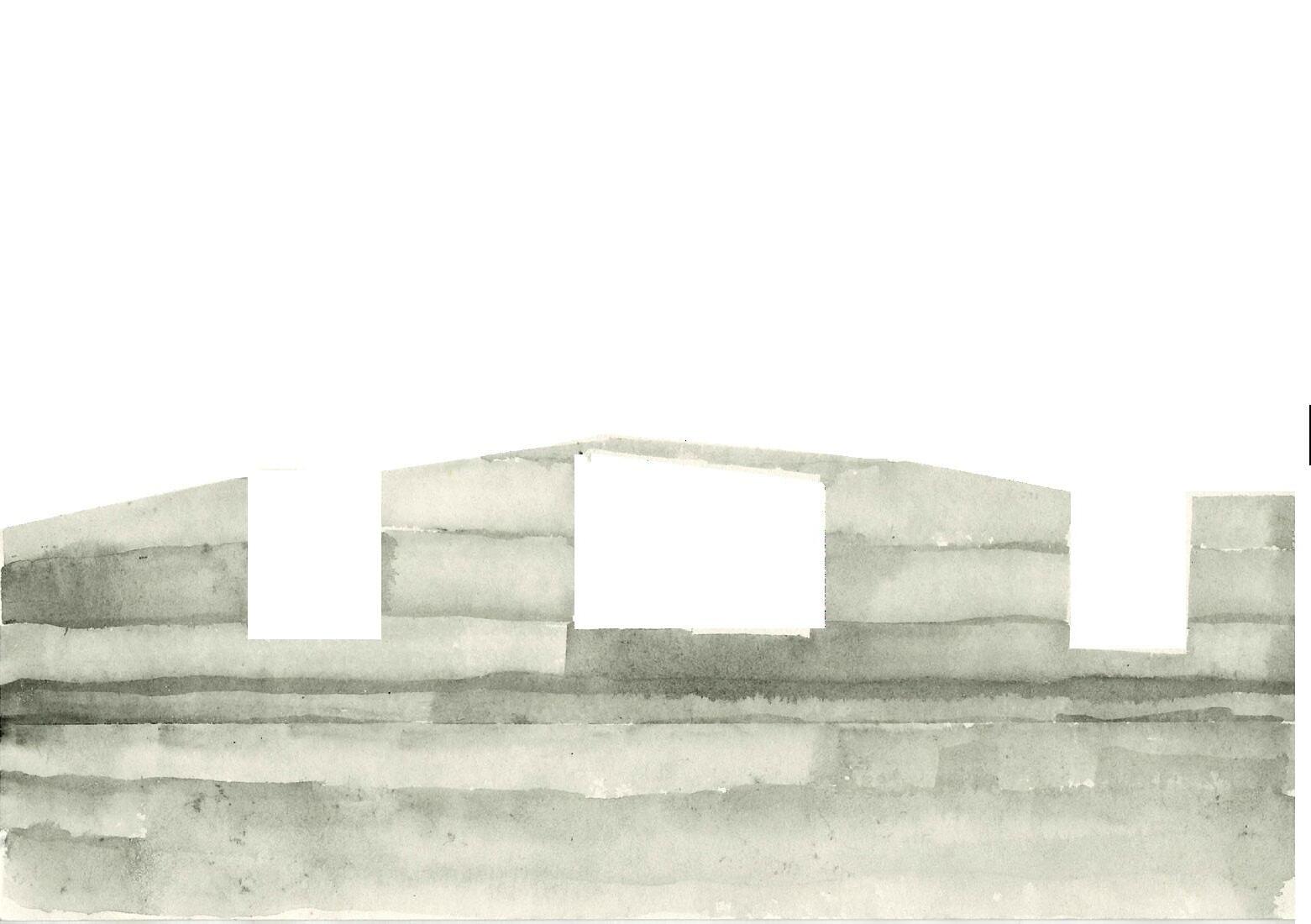

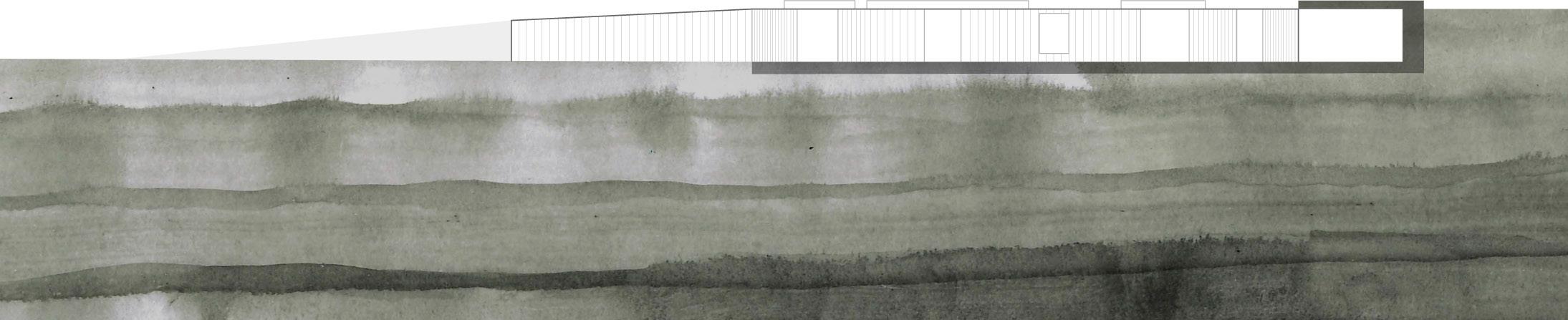

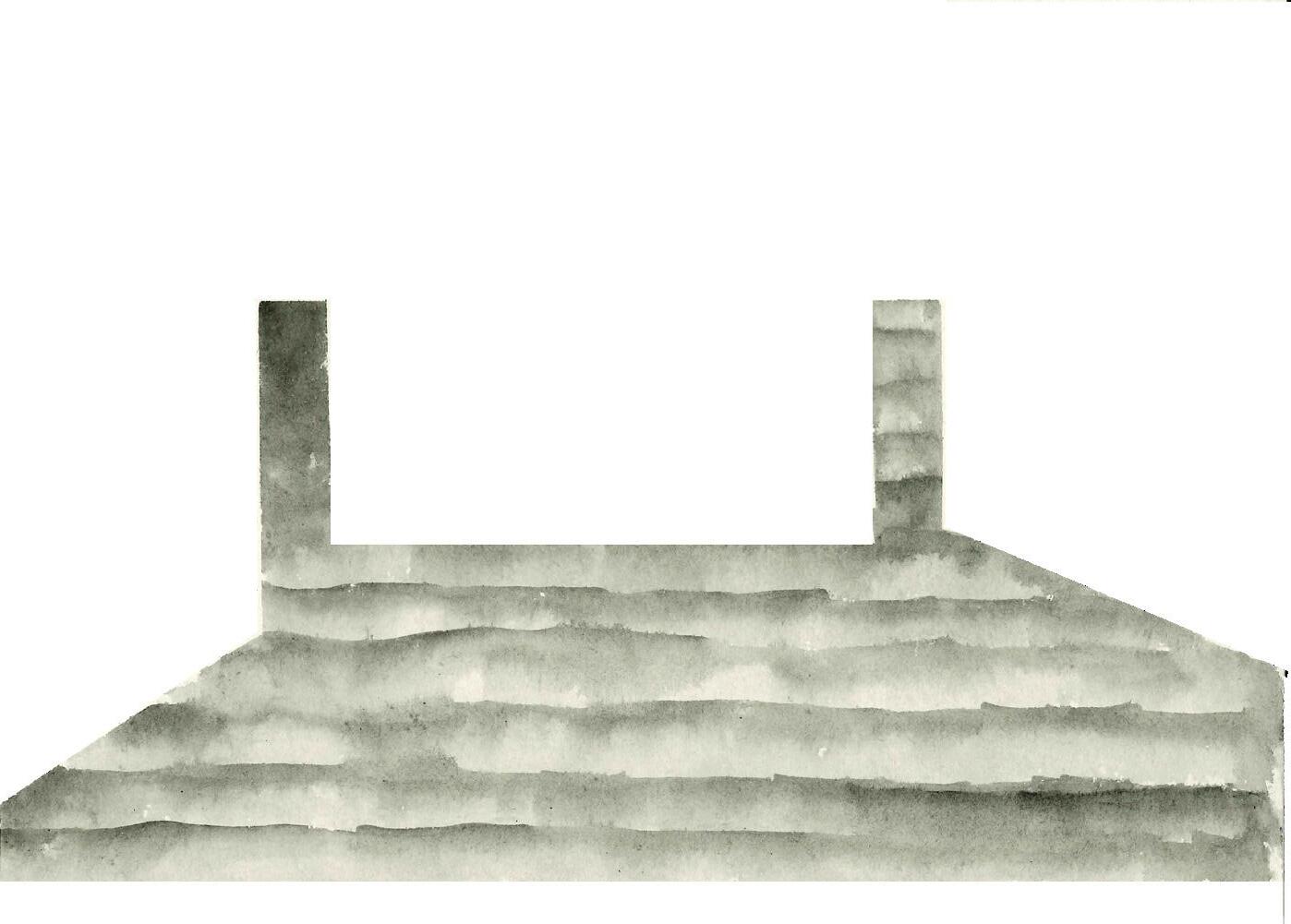

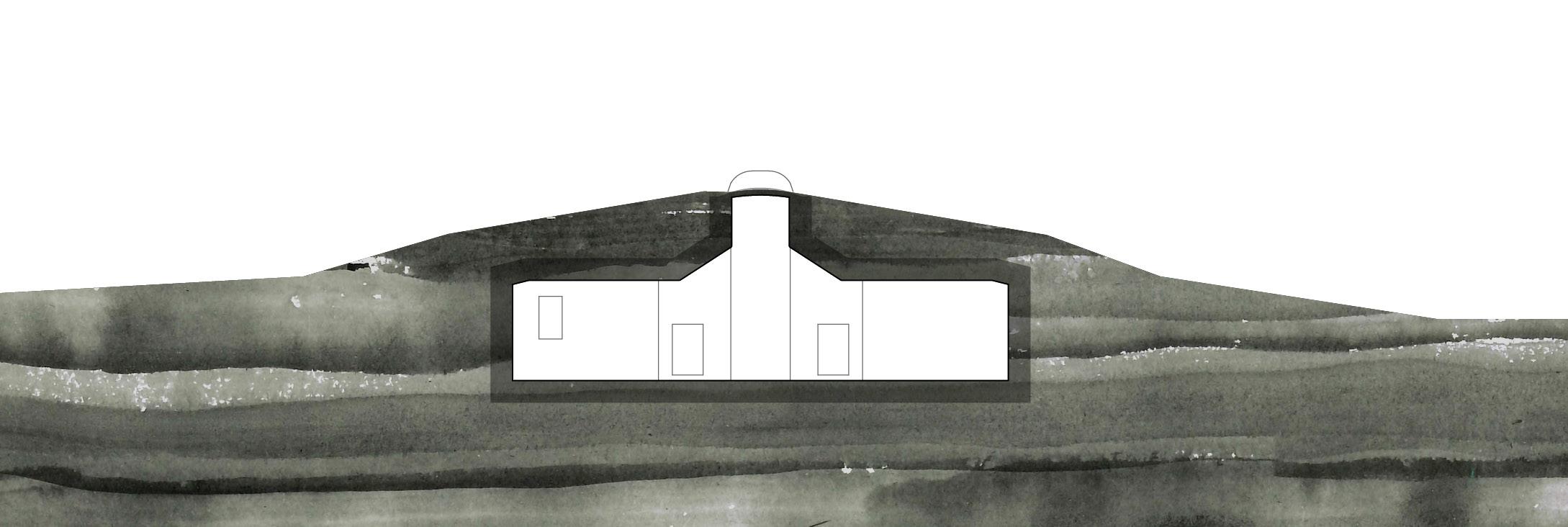

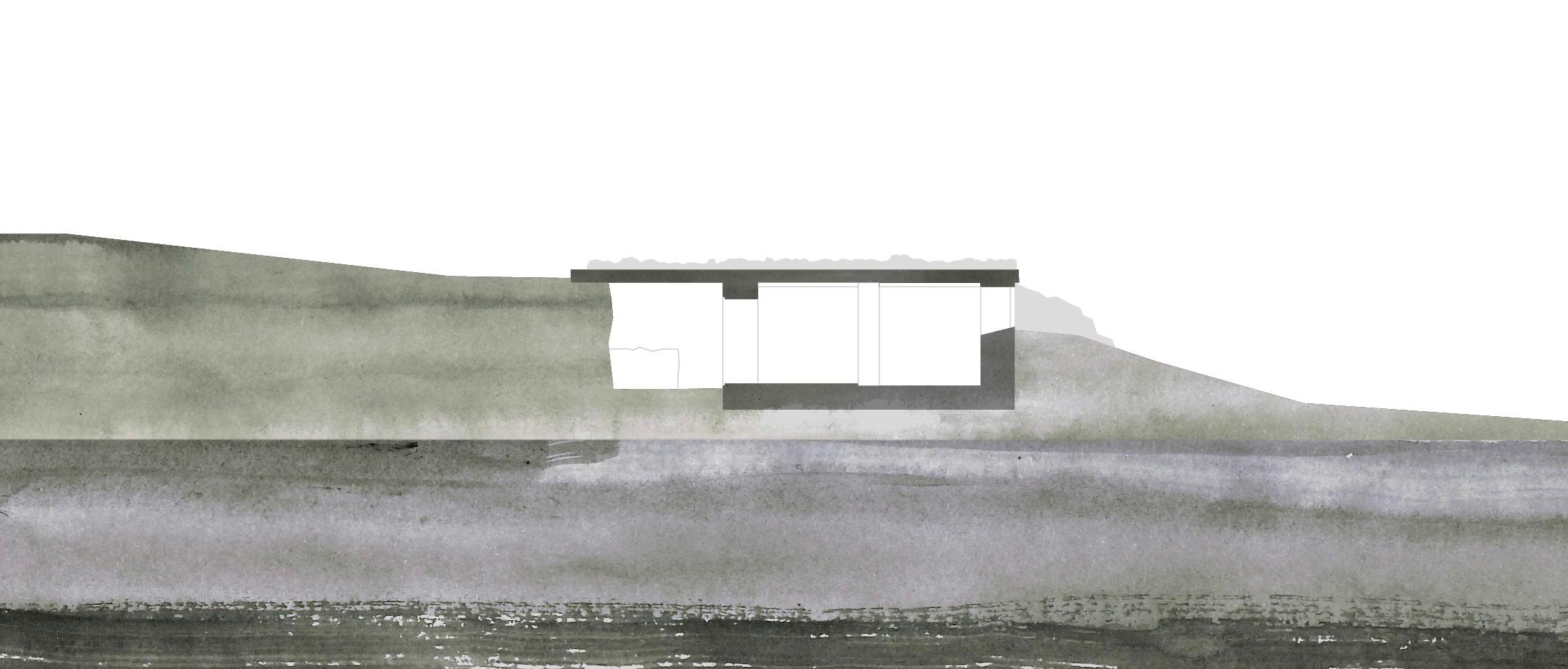

CASE STUDY: BREKSTAD PAVILION

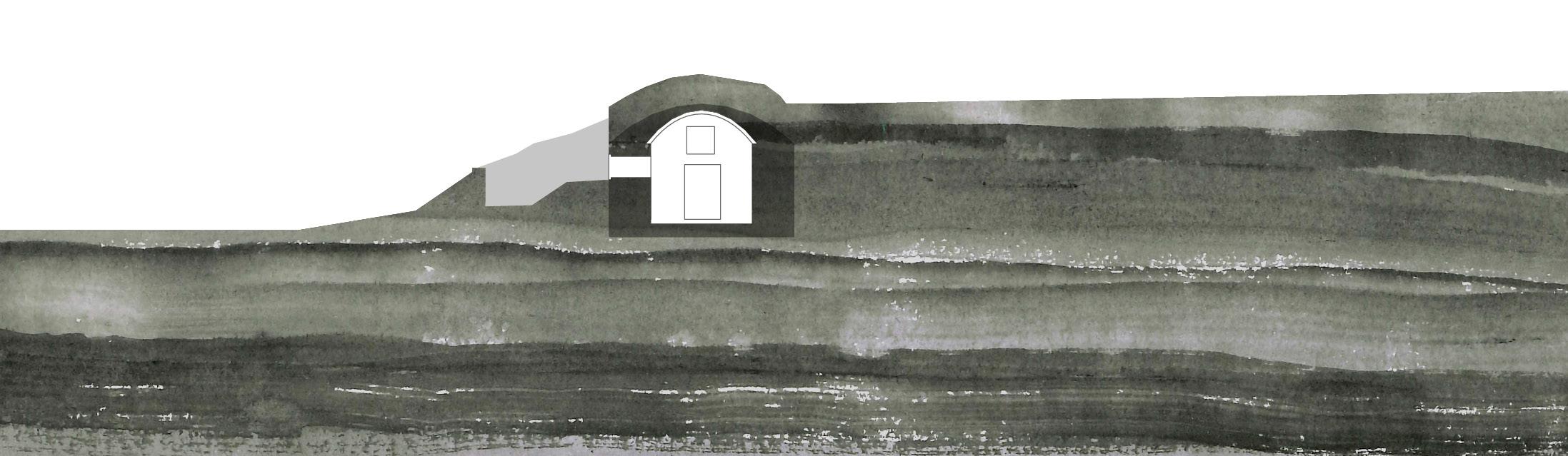

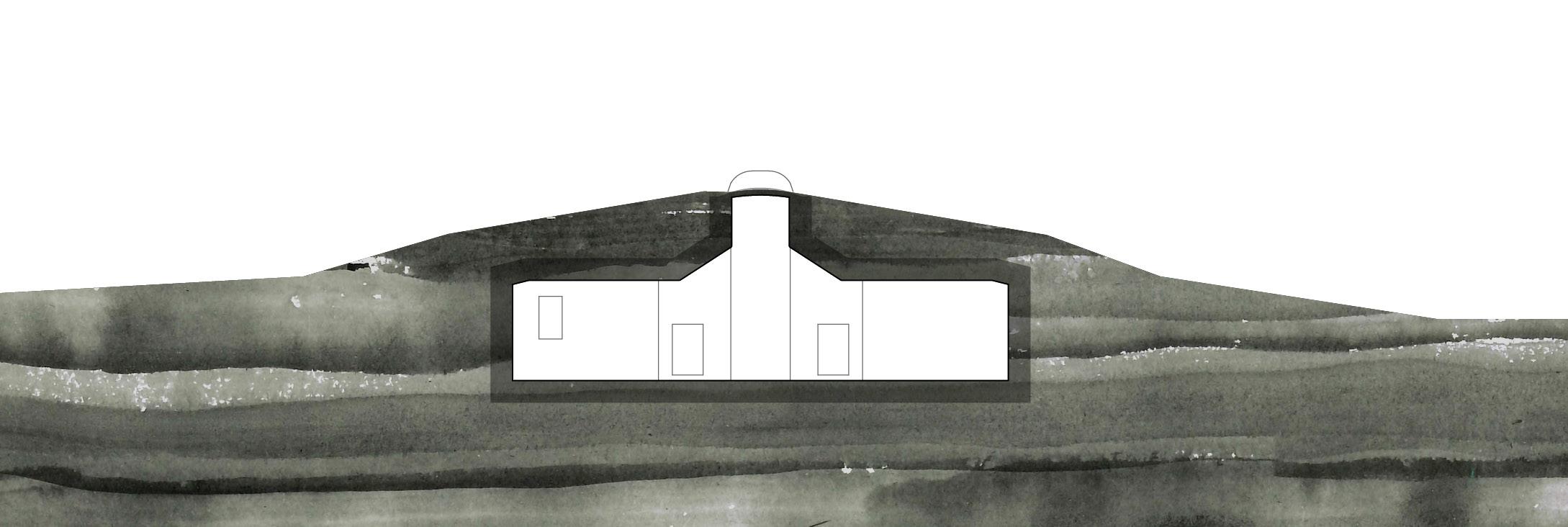

There are not many examples of transformed bunkers in Norway, but there is one located in Brekstad, Ørlandet. Located right next to his farm, the owner, Hans Kristian Norset, wanted to do something extraordinary with one of his bunkers. He both came up with initial idea, and built everything himself. During the process, he reached out to multiple architectural firms, like Snøhetta, for help with his visions. However, the design-proposals were bold, often consisting of quirky shapes and hard materials. Eventually he ended up with Asas architects, which had a local office and were more in tune with his vision.

57

59

This bunker used to be a German “Flak-position”, a type of anti-aircraft gun connected to an underground barack. The bunker was part of a bigger defense-system built for protecting the airfield constructed on Ørlandet during the war.

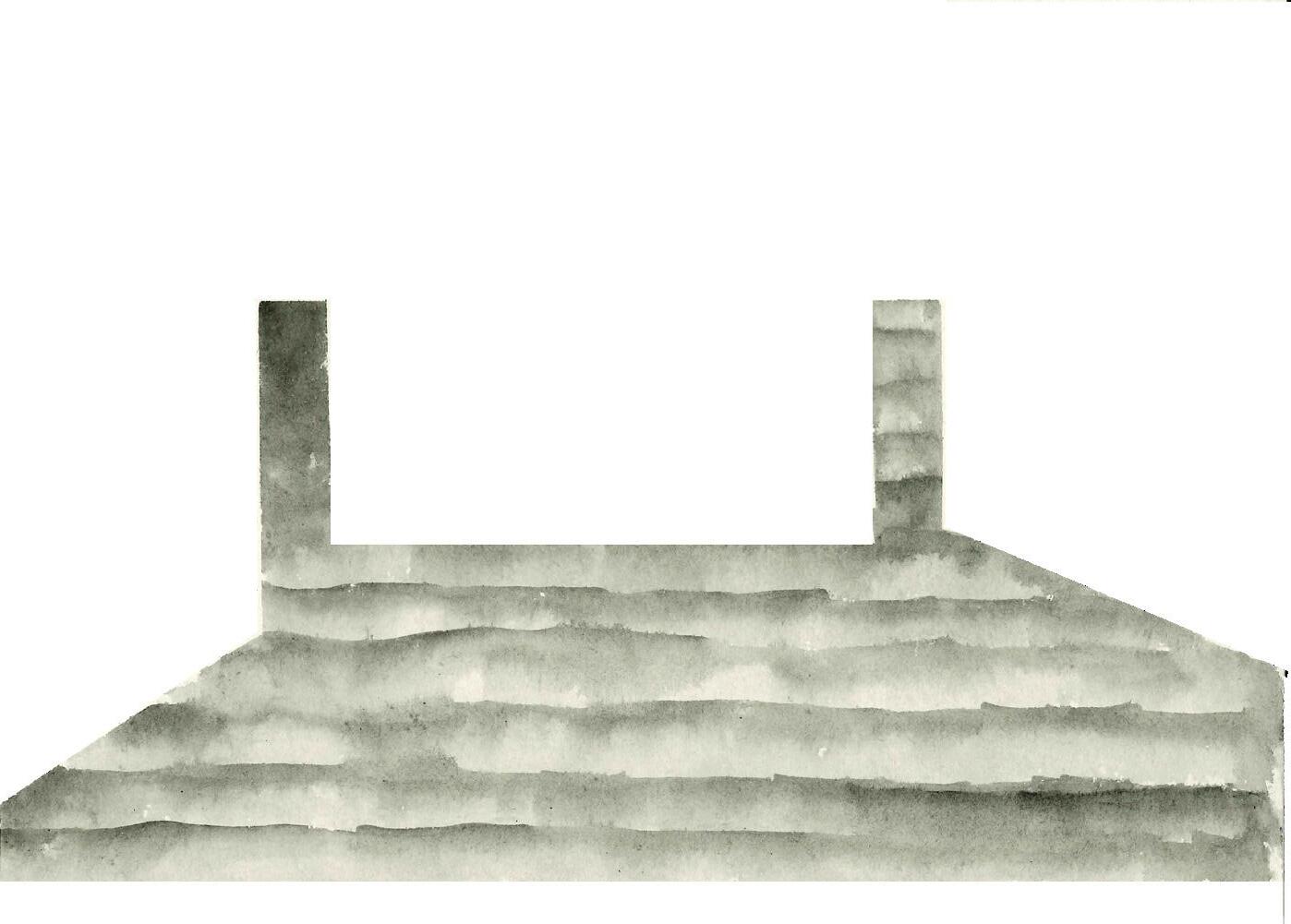

Hans Kristian started digging away all the soil around the bunker before filling it with drainage material, to prevent leaks in the thick concrete wall. He then demolished the concrete floor slab, digging into the soil and casting a new concrete floor, this enabled a taller ceiling height in the entrance hall of the structure. He then proceeded to cast a new layer of concrete on top of the old, both to strengthen the existing roof, but also create a taller space. Four steel column bases were cast into this new layer of concrete, creating the foundation for the new glass covered structure floating above the bunker. This construction consists of a concrete slab along with a wood cladded steel roof-truss system. Specially produced glass panes were then slitted into the concrete slab and fixed to the roof construction, creating a 360 degree view of the flat landscape on Ørlandet. Some of the glass panes were separated to create smaller operable windows framed with steel plates extruding into the space. A truly inspiring project, that strengthens our belief in that these structures can become functional and intriguing spaces.

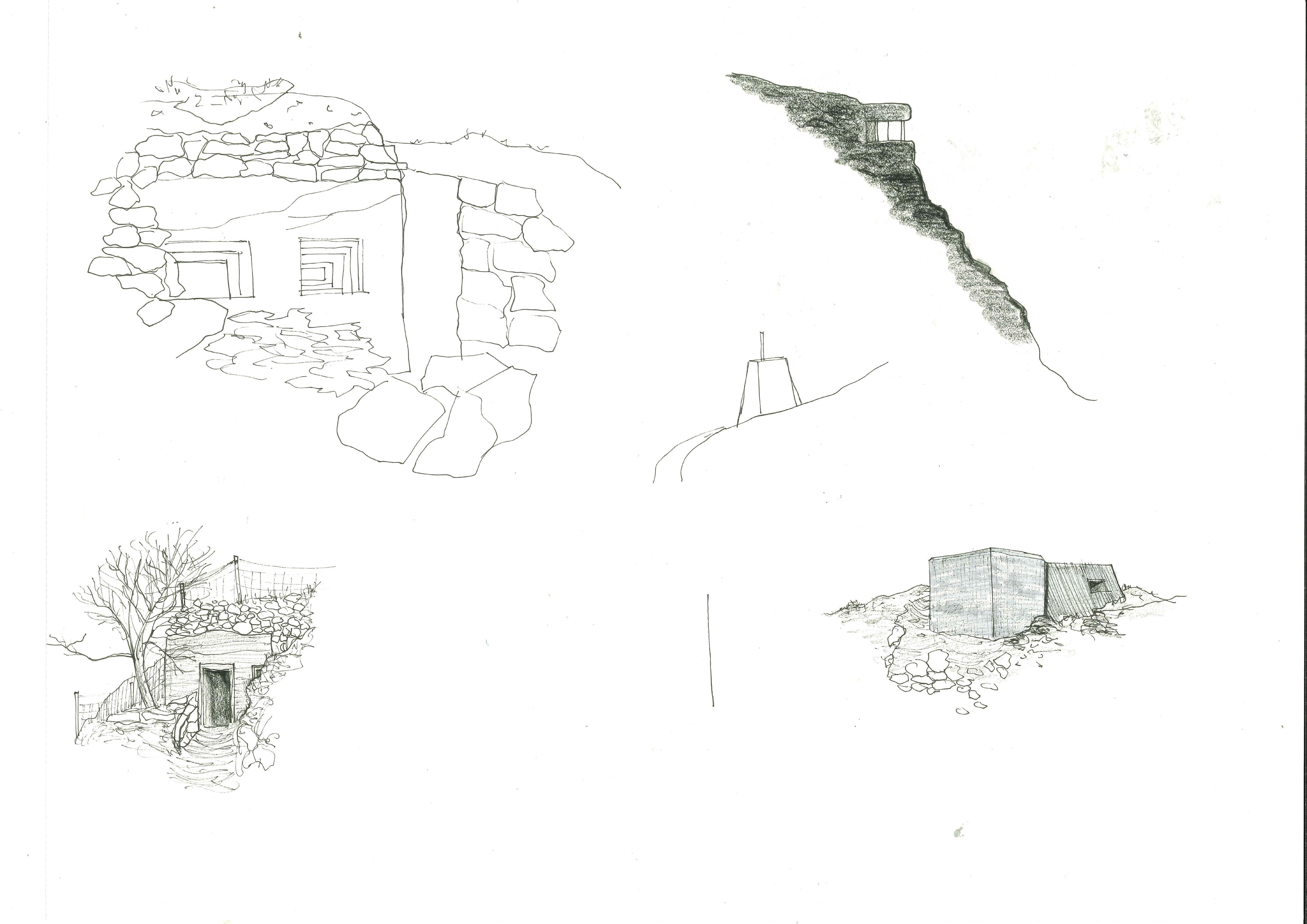

60

DETAILS

The Germans developed a system, “regelbau” for building fortifications, a set of replicable structures that could be ordered and built all across their occupied territory. The bunkers were planned down to the last detail, even how much concrete and rebars would be needed, making it a very effective system. In the book ”Atlantic Wall - Linear Museum”, Gennaro Postiglione states that the Germans ran into trouble when meeting with the rocky landscapes of Norway. Therefore they had to make adaptations, changing the layout of the bunkers to make them fit (2005).

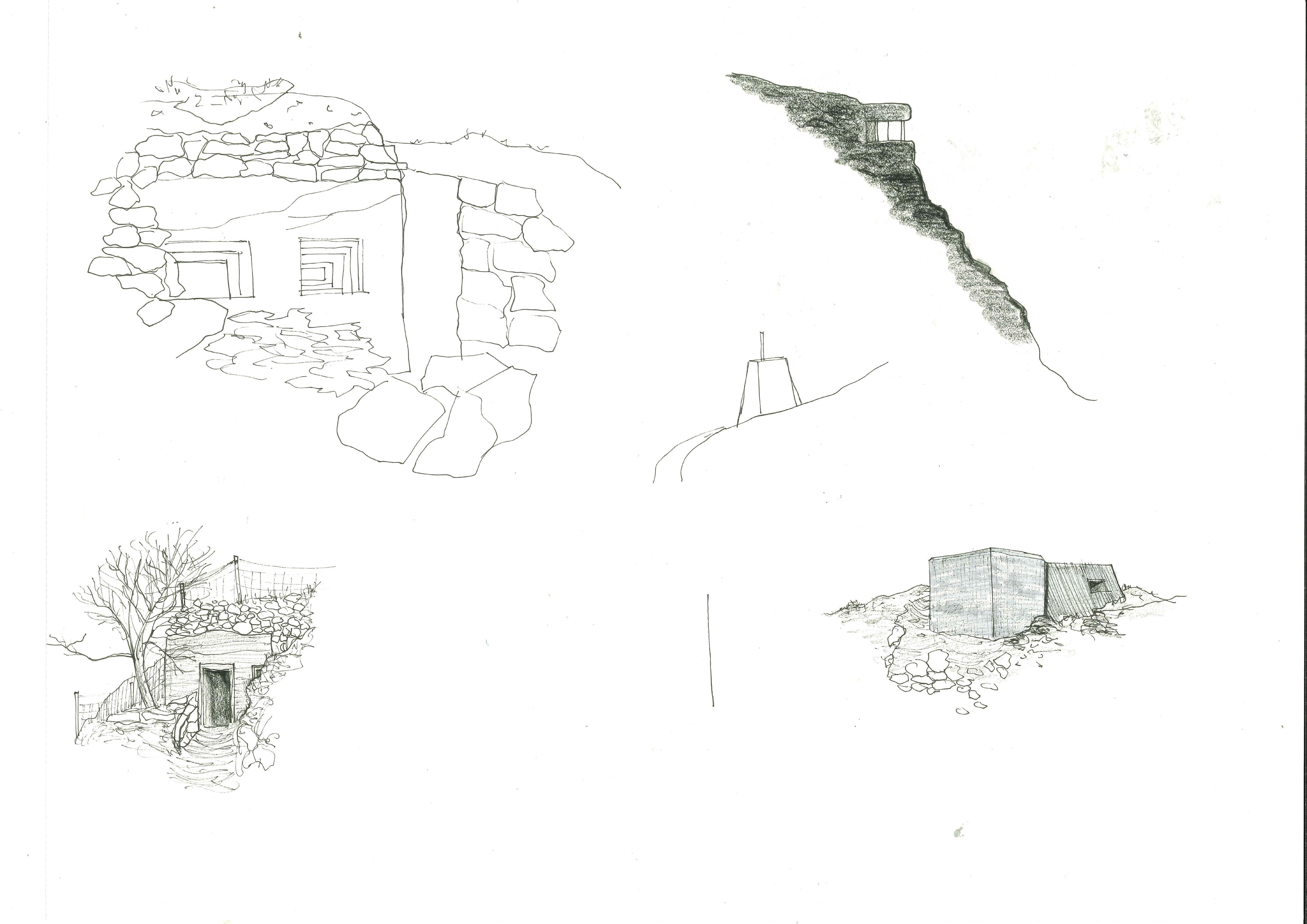

The wall surfaces were mainly made from in-situ concrete, often covered by a layer of rocks on the outside. The Germans understood concrete as a material, this reflects in the intricate details and durability of the constructions. They used the formwork to carve shapes into the concrete, creating inverted door frames to keep the water away from the opening and the stepping of the windows creating interesting articulation in the solid objects. Each structure was built using different formwork, further enhancing their character. Some of the interiors were cladded with wood and along with the wooden window and door frames the wood serves as a nice contrast to the massive concrete walls.

Amongst the precise concrete faces we were surprised to see a lot of make-shift details, deviating from the strict “regelbau”-system. A result of the scarcity during the war as much of the materials were swallowed by the German war-machine. They utilized what they had available, old railroad tracks became beams supporting the roof, repurposed corrugated steel sheets became doorways and quite frequently the solid concrete was substituted by natural stone with concrete mortar.

It has been almost 80 years since these constructions came into place. The patina is displayed in various ways, depending on their placement into landscape; to what degree they have been exposed to the sunlights and the quality of the concrete.

61

62

63

64

Textures

EUROPE

The long beaches of the European mainland were perfect for the Regelbau system. The structures could easily be cast on top of the flat landscape wherever they were needed, creating a solid and orderly defense line, with a great view of the coast. Additional lines of barbed wire and “hedgehogs” (anti-tank traps) were added for increased protection from possible allied landings.

However, during the time since they were put in place, some of the structures has started to fall into the sandy beaches.

65

66

NORWAY

The Germans had more struggles to fit these structures into the rocky landscapes of Norway. They had to either remove larger parts of earth, or make some adaptations to the regelbau, to be able to make them fit.

When the Regelbau system was applied to the rugged Norwegian coast, the Nazis ran into trouble. The Nazis were faced with a more difficult task of constructing their perfect defense line for the remainder of the Atlantic Wall. With small islands and islets obscuring the line of fire and potential enemy warships, cliff sides and rocky terrain making the Regelbau structures hard to incorporate into the landscape.

The extending and receding coastline characteristic of the Norwegian coast with fjords and inlets, demanded a well organized defense plan that would cover all sectors and flanks. Further impacting the positioning of the structure in relation to each other and the coastal landscape.

To us, they appear more as a part of the landscape. They are situated in the landscape, serving as an additional historical layer. In some places, it was almost impossible to draw the line between the structures and the landscape.

67

68

REFLECTIONS

After the trip we are left with a much better understanding of these extraordinary structures. How they were constructed, the simplicity with the high degree of precision expressed in the bare concrete. We were also baffled by the condition of this now 80 year old concrete, parts of it looked brand new. Further seeing how the clear geometrical shapes stand in contrast to the rugged nature, sticking out of while at the same time blending in with the landscape. The concrete as an artificial stone merging with the natural stones, speaking the same language.

We got to experience the reasoning behind the placement of the structures, where they were placed in the landscape and why. How some are dug inside of hills, becoming hidden disguised as natural formations, or placed on the edge of cliffs to create vantage points for overlooking the coast. The best locations for them to function for what they were intended to do, to wage war.

We got to meet a lot of hospitable locals, through talking to them learning how they relate to the fortifications. Seeing how they utilize them today, some of the structures were used as tool sheds or storage, others as pens for cattle, or turned into venues for concerts, some even transformed for residential use. They do have value to the locals, but not enough for them to look after the structures. It was inspiring to hear how thrilled the locals were with our suggestion of giving the structures new use, their excitement when talking about their own plans which were never completed. Ideas about what the local society would benefit from, which functions they felt were missing in their surroundings today, and their understanding of the importance of bringing these historical structures with us into the future.

69

REFERENCE LIST

Tanizaki, Junichiro. In Praise of Shadows. England: Vintage books, 2001.

Fjørtoft, Jan Egil. Tyske kystfort i Norge. Norway: Agder presse, 1983.

Zumthor, Peter. Thinking Architecture. Basel: Birkhauser, 2010, p. 95.

Kystmuseet. ”Hemnskjela under krigen”. Acessed 03.02.23 at [https://kystmuseet.no/hemnskjela-historie]

Store Norske Leksikon. Accessed 03.02.23 at [https://snl.no/]

Postiglione, Gennaro. The Atlantic Wall Linear Museum. Italy: Litogì, 2005.

All pictures and drawings are self produced, unless other is specified

71

72

DWELLING MONUMENTS

Ole Flatebø William Horstad

Peter Zumthor

Peter Zumthor

Extract from travel-journal

Extract from travel-journal