3 minute read

A CROSSING OF THEIR OWN

Colorado civil engineer John Kronholm ’93 helps all manner of animals get to the other side of dangerous highways

—BY KATE LAWLESS

As a child growing up in rural Blandford, Massachusetts, John Kronholm ’93 loved the outdoors. He built dams in the driveway when it rained, he loved camping with his scout troop, and he pored longingly over the pages of Ski Magazine. After two years at Williston, he attended Union College, double majoring in civil engineering and geology. “To me, that path between engineering and connection to the land was civil engineering,” he said from his office in Eagle, Colorado, where he’s a Design Team Manager at the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT). For the past 10 years, among other projects, he’s been working to create overpasses and underpasses for wildlife crossing state highways.

Kronholm began his career in Virginia, but it wasn’t long before he took off to Colorado in 1999, bound for big mountains covered in powder. Around that time, Coloradans were seeing more animals hit by vehicles on highways. Two endangered Canada lynx were killed following the reintroduction of the species there.

State agencies and conservation groups were realizing that major roads were making it difficult for wildlife to complete their migrations, and that the reduction of their habitat, so fragmented by human development and infrastructure, was impacting biodiversity. Road ecology became a movement to create highway crossings for wildlife.

Kronholm saw that he could be part of the solution in 2016 as the Project Manager of an environmental assessment of Vail Pass. He’s currently working on crossings under that stretch of Interstate 70, which passes through the Eagle Valley amid the Rocky Mountains. There, he set up trail cameras, trying to find the areas where iconic Western fauna cross the road—animals such as Canada lynx, mule deer, pronghorn, bighorn

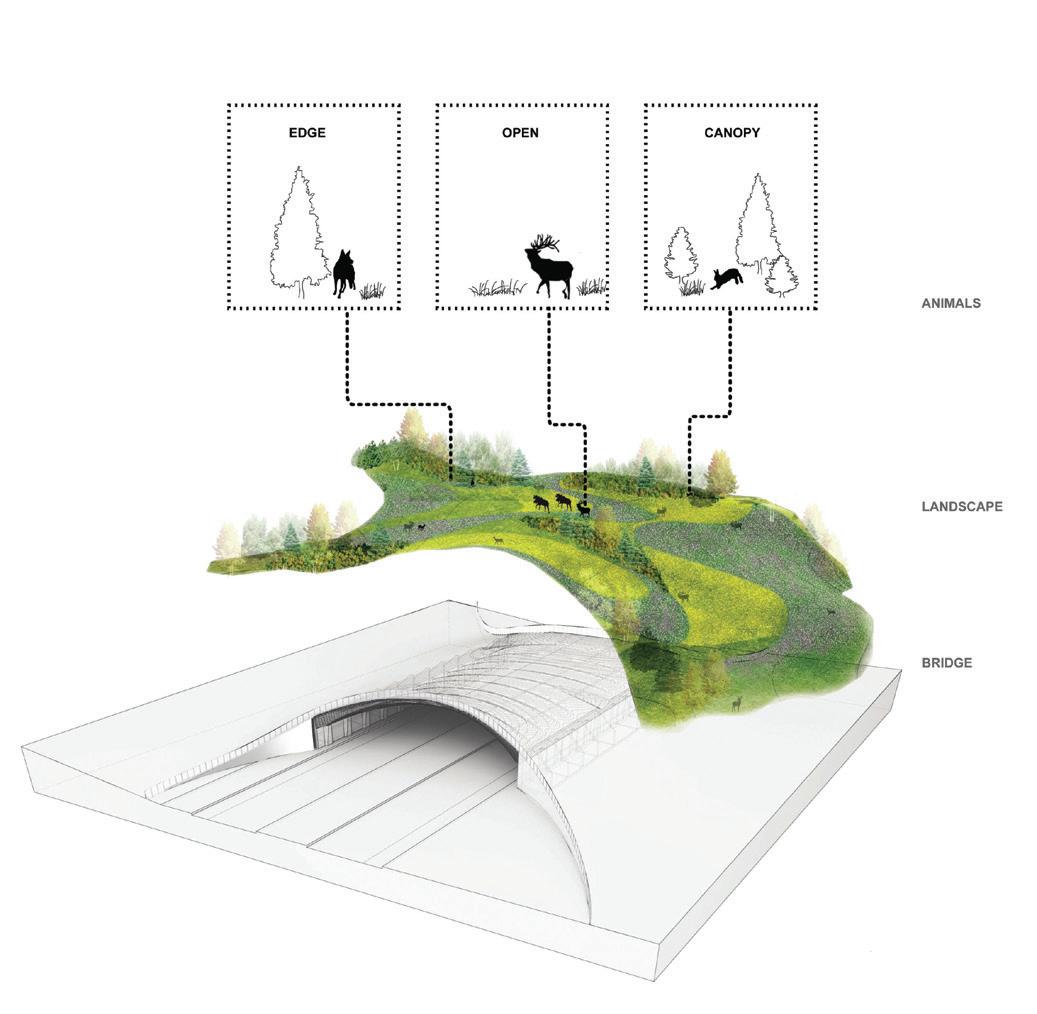

Above: How designers create corridors for various animals on the move

sheep, elk, and smaller mammals like marten, bobcat, coyote, red-tailed fox, short-tailed weasel, snowshoe hare, and yellow-bellied marmot.

“I’ve documented herds of elk coming down to the highway, hanging out by the road, and then going right back up and not even trying to cross it.” In fact, locally the elk herd has declined by about 50 to 60 percent in the past 10 years, as documented by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Wildlife-vehicle collisions and habitat loss and fragmentation contribute to this decline.

CDOT’s $170 million I-70 West Vail Pass Auxiliary Lanes Project will construct six new wildlife underpasses, two large and four small, adding to the already 63 in place throughout the state. Kronholm, working with CDOT’s Applied Research and Innovation Branch, also has put together a literature analysis and study to determine wildlife crossing structure size. The hypothesis that Kronholm derived was that an optimum size of wildlife crossing structure could be determined though a statistical analysis of published and unpublished data. Kronholm’s fieldwork and literature study helped to influence the sizes and locations of the crossings on Vail Pass.

While crossings are expensive— between $2 million and $3 million per structure—they save lives and money. Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association noted that 3,300 animal-vehicle collisions happen each year in Colorado and, nationwide, insurers pay out $1.1 billion worth of claims for these accidents, some of which have caused deaths and injuries to drivers.

Once crossings are in place, it could take three to four years for animals to develop the trust to use them regularly. For Kronholm, when that happens, it means his work is making a difference.

He still loves the outdoors and frequently goes camping and backpacking in the Rocky Mountain wilderness, now sharing those adventures with his 14-year-old son, Ben. “In Colorado,” he says, “seeing a herd of elk or seeing deer when you’re out camping—it is amazing.”

He views his work as helping preserve those experiences, while improving driver safety. “What we’re trying to do,” he says, “is strike a balance.”