3 minute read

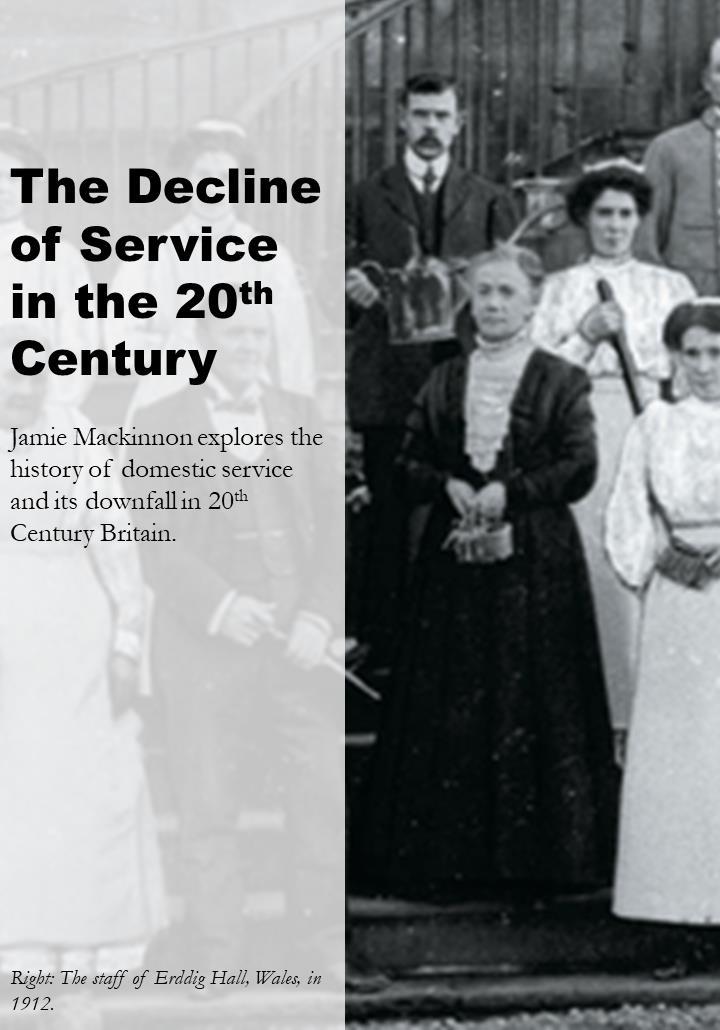

The Decline of Service in the 20th Century

Delftware, or Delft Blue, is a term used to describe the tin-glazed earthenware that emerged in the city of Delft in the Netherlands in the 17th Century. It was known for using Chinese designs and templates, and provided pottery of great quality, but at a much lower price than that of Chinese porcelain. The arrival of Oriental porcelain into Europe was extremely important to the growth of Delftware, and both the emergence and the significance of Delftware in 17th Century Europe are useful studies. Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, a Dutchman who travelled to India with the Portuguese, was the first person to write about porcelain in China for audiences in the Netherlands. He described pieces that he saw in Goa, as so perfect that “no crystalline glass can be compared to them.” While Van Linschoten certainly got many traders excited about porcelain, traders in the years after did not access it legally, and nearly always resorted to piracy. Companies like The Dutch East India Company (VOC) gained their first hauls of porcelain by capturing foreign ships. For example, The VOC seized the 1500-ton Portuguese carrack the Santa Catarina off the coast of Singapore. She was such a rich ship that her sale proceeds increased the wealth of the VOC by more than 50%. The huge amounts of Ming Chinese porcelain taken from the ship led Chinese pottery to be known in Holland as “Kraakporselein”, or “carrack-porcelain” for many years. The piracy increased to such levels that the Dutch had to set up direct trading links with the Chinese if they wanted to keep a constant supply of porcelain into Europe. Yet the Chinese put great restrictions on the trade. Dutch traders were forbidden to travel to China. They were forced to collect the porcelain from Batavia (now Jakarta), a Dutch trading outpost. The Chinese emperor also required merchants to pay homage to him in order to maintain their trading agreements. This, as well as the death of the Wanli Emperor in 1620, meant that the supply to Europe was interrupted, and the price rose dramatically. European Potters saw an opportunity to produce a cheap alternative to Chinese porcelain. This new tin-glazed earthenware technique was used all around Europe, but it was perfected in Delft. This success is often attributed to the quality of Dutch clay, which allowed potters to refine their technique and make finer items, and to the easy access that potters in Delft had to Chinese originals from the VOC. Chinese porcelain was already very expensive, and the shortage drove up the price, but Delftware provided a cheap alternative for porcelain. This provided the middleclasses with access to near replicas of goods that only the richest could afford. Delft potters were also ready to innovate, with the creation of earthenware teapots to prepare all the tea that was brought back to Europe by the VOC. Delftware shows the appetite for Oriental goods in Europe because it shows that people were looking for a cheap alternative to the expensive and poorly supplied porcelain. They wanted the beauty and respect that came with porcelain, but at prices that most professionals could afford. The appetite was certainly there, as 33 factories operated at the height of Delftware, and they were able to provide accompaniments to the other goods, such as silk, tea, and spices, which came from the Orient, but for a better price.

‘Armorial Dish’, by Willem Jansz. Verstraeten, c. 1645-55

Advertisement

For Comparison: ‘Windswept’ Meiping, Ming Dynasty, Mid-15th Century