10 minute read

JOSH SWAN

South Shore Boat Builder

BY LISA LUDWIGSEN

Advertisement

Highon a rise outside of Washburn, with Lake Superior sparkling in the distance, sits the workshop where Wisconsin native Josh Swan builds and restores wooden boats. The bright and spacious building he constructed, along with his nearby house, sits on the 50-acre property he shares with his young family. The shop smells of freshly hewn wood and is stocked with dusty books, manuals, charts, family photos, and lumber waiting to be transformed into a custom boat. Across a field is the sawmill he uses to mill lumber for his own projects and lumber he ships to places near and far. The setting is classic, unspoiled, wooded northern Wisconsin. Swan is energetic and excited about his craft, even after more than twenty years in business.

In an essay he wrote about his profession, Swan explains the relevance of boatbuilding in Wisconsin. “Centered on the royal blue background of the Wisconsin state flag is a golden seal divided into four sections. A plowshare in the upper left represents agriculture. In the upper right, a shovel and pickaxe, tools of labor celebrating the lead mining that fueled much of Wisconsin’s early European migration. In the lower right, a classic kedge-style anchor, honoring Great Lakes shipping. Finally, the lower left-hand corner bears a well-muscled arm holding what looks like a hammer. That hammer is a caulking mallet, a very specialized boatbuilding tool used to drive oakum and cotton into the seams of a wooden-planked hull to make it watertight.”

Oakum was traditionally made of reused fibers such as old rope or hemp dipped in tar to provide insulation in construction and gaskets in plumbing. Teasing apart the used fibers, particularly those coated in tar, was tedious, painful work, often performed by prisoners or low-level laborers whose fingers would split and bleed in the process. Oakum fiber is especially useful in wooden boat construction because, when packed between planks with pitch or tar, it provides a flexible water seal as planks swell and shrink over time. Oakum is still in use today.

That caulking mallet lauds the centuries-old tradition of building and using wooden boats to ply the rivers of Wisconsin and the waters of the Great Lakes. From wood-framed Native American canoes, to near shore small craft, from barges and fishing tugs to much larger schooners and tall ships, the boat building industry was, and remains, essential in the development and economy of the Great Lakes region. Hulls of sturdy old fishing boats from the 19th and 20th century can still be seen dotting the landscape in waterfront towns, a testament to the history of the region and to their durability. The nearby town of Bayfield, on the Apostle Islands National Seashore, has incorporated old hand-built boats into a city park and one even adorns the front yard of the Bayfield Heritage Museum.

Today, the building and re-fitting of large boats, yachts, and ships continues in Wisconsin ports such as Marinette, Green Bay, Sturgeon Bay, Manitowoc, and Superior. But such vessels typically are built of steel and other non-wood materials. By contrast, any given day a visitor to Josh Swan’s workshop might find a beloved family rowboat from Isle Royale in mid-restoration, or the beginning design of a commissioned project to recreate a boat from decades ago. Outside sits a 20-foot sailboat in mid-construction. It turns out that nostalgia figures into a large portion of Swan’s business. Clearly, wooden boats represent, for some, a visceral memory or a romanticized notion of a time gone by. Whatever the individual pull, the appeal of wooden boats is enduring.

That nostalgic affection and mystique extend to Swan himself, as he works to fill a steady stream of orders from across the region, around the country, from Canada and beyond. He also mills and ships boat lumber as an adjunct to his boat-building business model.

Swan’s career wasn’t a predictable choice, given that he did not grow up on or near the water, though he did go lake fishing with his father “in a beat-up aluminum boat that we patched with duct tape.” He now uses that boat from his childhood to take his own two kids fishing. He explains, “I always had an interest in woodworking and thought learning how to build wooden boats would teach me relevant and transferable skills to a career in woodworking.” After high school in Eau Claire, he moved to Newport, Rhode Island, to study and work at the International Yacht Restoration School

(IYRS). “When I got there, I was an anomaly,” he says. “Everyone at the school came there by way of sailing, or crewing on a sailboat, or wanting to crew on a boat. They shared the common romance with tall ships or were big time sailors.”

Surprisingly, as another influence, he credits music. “I guess I can attribute some of my interest in boats to listening to Stan Rogers, a Nova Scotian maritime folk singer, when I was in high school, but that’s about it. Somehow, I was able to connect these weird dots to end up at the school.” Once enrolled at the IYRS, “the rules, skills, and results of traditional wooden boat construction captivated me, and my professional focus has remained on wooden boats ever since.”

While many careers meander over time or take sharp unexpected turns, Swan’s path has been fairly linear, building on his unique blend of skill, craft, art, education, and experience. He’s fortunate to have found mentors and opportunities that met his interests and passions. After the IYRS, Swan spent two seasons as Boatbuilder-in-Residence at the renowned Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake, New York, and then spent a winter working with Jack McGreivey at McGreivey’s Canoe Shop in Cato, New York. He spent time as Artisan-in-Residence at the UW–Madison Department of Art, working with students to build a traditional inshore boat called a Maine Coast Peapod. Through a grant from the Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle, he spent six weeks at the Hardanger Fartoyvernsenter, a waterfront boatyard museum in Hardanger, Norway, focused on keeping alive the relationship between a village and its place on the water. It’s fair to say that Josh Swan knows boats—large boats, small boats, even bark and canvas canoes.

Wooden boats have an enduring allure that captivates many people. Small wooden boats are relatively simple in design, and yet are also sophisticated crafts with a long history. They need to stay afloat through various conditions and over time, and they need to meet the practical needs of transporting people and goods. The oldest known boat is the Pesse canoe, a carved-out pine log found in the Netherlands that dates to around 7500 BC. A similar 28-foot pine dugout canoe estimated to be 1,000 years old was recently discovered in North Carolina, and in 2021 and 2022, two Ho-Chunk Nation white oak dugout canoes, aged 1,200 and 3,000 years old, were discovered partially submerged in the lakebed of Lake Monona. These similar vessels were created thousands of miles apart out of need and available material.

Indigenous people created lightweight, durable vessels using basic tools, and Native American canoes made of bark or skin hold a mystique all their own. When Europeans arrived in North America in the 16th century, they discovered indigenous people deftly navigating waterways that their bulky wooden rowboats could not. Eastern North American tribes crafted bark or animal hide canoes stretched over a frame of moldable wood. Impressive examples of form and artistry, the boats were lightweight, durable, and highly functional. Those designs inspired the large bark canoes European traders used to explore the waterways of North America. The Bayfield Heritage Museum has on display an authentic Anishinaabe bark canoe constructed by Marvin Defoe of the Red Cliff Anishinaabe. Made of birch, cedar, spruce roots, and pine pitch, the canoe is impressive in its mix of art and function.

Alaskan Inupiat and others constructed boats from seal skins, and people of the Pacific coast bound together multiple tight bundles of spongy, hollow wetland tule reeds to make canoes capable of traversing great distances. The need and available materials begat the vessel.

Materials are important in boat-building, and so is craftsmanship. “Jack McGreivey was an interesting old guy who had the grace and patience to let me work in his canoe shop. One aspect of his process that left an impression on me was that when he repaired or rebuilt canoes, he didn’t conceal his work. Though his craftsmanship was excellent, he didn’t mask the patch or new wood with chemicals or techniques to make it blend in. I’ve always appreciated that by leaving those details visible, they tell the story of the boat.”

After two decades, Swan speaks of becoming more discerning with his time and energy, but he still emanates a contagious enthusiasm for his craft, creating something new based on those age-old concepts. A typical project, and a recent favorite of his, is the reconstruction of a skiff (a shallow, round-bottomed boat with pointed bow and square stern) that a retired Wisconsin fire chief used when he was a lifeguard on Lake Michigan in the 1970s. The man searched unsuccessfully for a model to restore before hiring Swan to recreate it from scratch. He sent Swan basic measurements of length, width, and depth in the middle. “He reached out to me with those measurements and sent a set of faded photos of an original boat. I then designed and built the boat for him,” said Swan. “What’s cool about this boat is that I harvested all the cedar out of Bayfield County, and milled all the wood in the boat.”

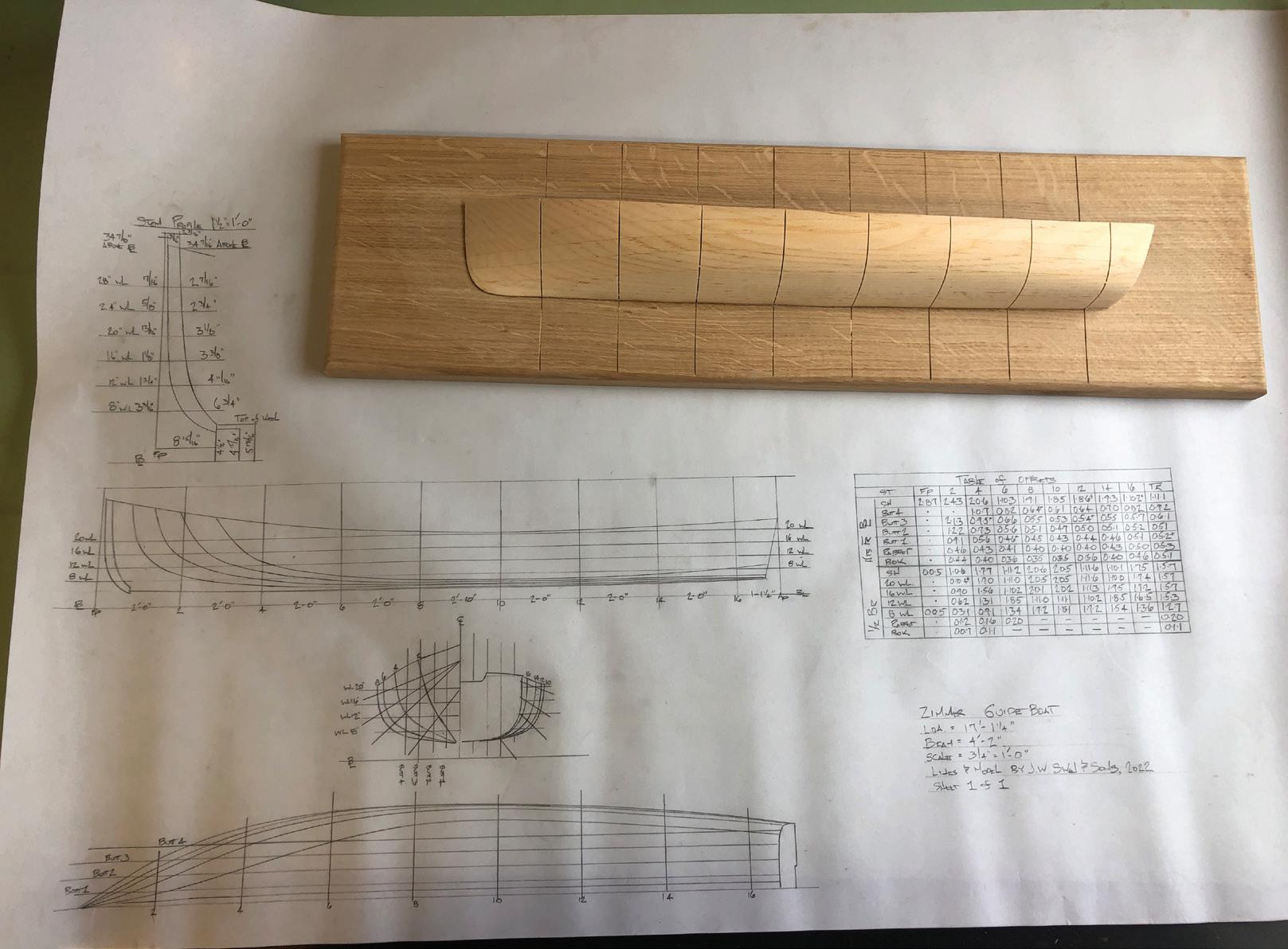

Swan’s design process is decidedly traditional. There is no computer-aided designing in his workshop. It is all done by hand. After designing a boat on paper, he lays out or “lofts” the boat to scale on the floor. Lofting is a drafting technique used to map out curved lines in the building of airplanes and ships. Watching him do this while he narrates the process, you can see his love of this work.

One of Swan’s favorite books is The Survival of the Bark Canoe by John McPhee, a short but compelling account of a 150-mile journey through the Maine woods the author took in the mid 1970s with a bark canoe builder named Henri Vaillancourt. Passages describing Vaillancourt’s purposeful focus and knowledge while sourcing trees for his birch bark canoes likely have influenced Swan’s desire to harvest and mill lumber for both his own projects and his business.

“When I worked at the Adirondack Museum, we would visit small sawmills nearby to purchase lumber for our boat projects,” says Swan. “Something about those sawmills and the people who operated them really grabbed me. It made a big impression.” He adds, “I realized that I have a true affinity for being outside, and that the primary side of the boat building process appeals to my love of good hard labor. Being physically tired at the end of the day is important for my mental and emotional health.” When he returned to southern Wisconsin, he viewed the forests from a new perspective. “One day I needed lumber for a project, and suddenly my milling business began…Now that I’ve been doing it awhile, a growing part of me wishes I didn’t see each tree as a commodity first. While I recognize the intrinsic value in the beauty that surrounds me, my mind reflexively spots boat parts when I look at a tree—a transom knee for a rowboat in a curving oak branch, planking stock in the clear stem of a tall White Pine. And with every tree I cut down, I know I am leaving a footprint. I am quick to remember that any place I may walk with my saw and gear, I will always be stepping in the footprints of woodland giants.” The idea that a forest is a living breathing entity isn’t lost on Swan. He works with friends in forest management who guide him in balancing lumber harvest with the forest’s wellbeing.

Today Swan’s milling business is primarily for boat lumber, because that’s what he knows and what he does, but he’s also happy to help with milling for neighbors or other builders. “I sent a pallet of white cedar to an architect in California whose client was looking for wood with a lot of character. That lumber wasn’t appropriate for a boat but was perfect for a home interior project.” He continued, “People ask me all the time, ‘what’s the best boat building wood?’ My response is usually ‘whatever is local’, which can mean lots of different things. Wisconsin has a ton of great boat building lumber.”

Swan estimates there are a dozen or so professional wooden boat builders in Wisconsin, with a variety of specialties. There is plenty of work restoring classic mahogany runabouts, like Chris Craft or Century boats. “Though they’re beautiful boats, the fine detail work in those restorations is not what I enjoy doing,” admits Swan.

In an age of digital marketing, social media, and search engine optimization, Swan enjoys an almost analogue business model. “Yet,” he says, “when people ask about the most useful tool in the shop, my answer is ‘the internet.’” Most of his business comes from word of mouth or through his website. Orders for lumber, especially from Canadian customers, come through online searches. At any given time, he has eight to ten projects lined up, in addition to his milling work, but his business isn’t designed to scale up. “It works because of the scale of it,” he says. “I want qualitative development rather than geometric growth.”

Swan’s greatest challenge in his one-man operation is time management. “I’m continually trying to figure out how to work smarter while budgeting time for my family and all the rest. I also want to make sure that I can keep doing this work as I get older. After twenty years, I can feel the importance of taking care of myself.”

About his 1,000-yard commute from home to work, Swan wrote in his essay, “It is here that I remind myself that the eighteen-year-old me would be so excited to know the forty-year-old me is still walking through a bit of woods to my wooden boat shop and sawmill.”

As he goes about his work, he returns to that simple caulking mallet on the Wisconsin flag, integrating his relationship to those early boat builders, the wild origin of the lumber used to make those boats. “I try my best to make real the beautiful myth of Wisconsin.” The wooden boats he designs, builds, and restores are a testament to his success and to his place in the tradition of wooden boats in our state.

Lisa Ludwigsen lives in Northern California and Bayfield, Wisconsin, where her great grandparents immigrated from Norway to fish commercially on Lake Superior in the early 20th century. For over 25 years, her focus has been on food, farms, and families, as a small-scale farmer, environmental educator, business owner, and writer.